I Why The Classics

Bei Dao Zbigniew Herbert Zagajewski R. Carver Milosz Bolano Poems Charles Simic Brodsky Borges Cavafy_Ithaca Octavio Paz Thu 2013 NXH's Poems of the Night Lửa & Khoa Hữu & Celan TNH Poems Haiku_Buson Xmas 26 Dec 1999 Mark Strand Mahmoud Darwish W.S. Merwin TTT_9_Years Trang thơ Dã Viên The Lunatic by Simic Map by Szymborska Serbian Poetry ed by Simic Baczinski by AZ A Defense of Ardor by AZ Thơ Joseph Huỳnh Văn Emily Dickinson 1 Wallace Stevens Tomas Transtromer Paul Celan Cầu Mirabeau Cesar Vallejo |

Album | Thơ | Tưởng Niệm | Nội cỏ của thiên đường | Passage Eden | Sáng tác | Sách mới xuất bản | Chuyện văn

Dịch thuật | Dịch ngắn | Đọc sách | Độc giả sáng tác | Giới thiệu | Góc Sài gòn | Góc Hà nội | Góc Thảo Trường Lý thuyết phê bình | Tác giả Việt | Tác giả ngoại | Tác giả & Tác phẩm | Text Scan | Tin văn vắn | Thời sự | Thư tín | Phỏng vấn | Phỏng vấn dởm | Phỏng vấn ngắn Giai thoại | Potin | Linh tinh | Thống kê | Viết ngắn | Tiểu thuyết | Lướt Tin Văn Cũ | Kỷ niệm | Thời Sự Hình | Gọi Người Đã Chết Ghi chú trong ngày | Thơ Mỗi Ngày | Chân Dung | Jennifer Video Nhật Ký Tin Văn/ Viết

Tin Văn

& NQT

Thơ Mỗi Ngày

Rain

In Lima ... In Lima it's raining foul water from a mortifying sorrow. It's raining through the leak of your love. Don't pretend that it's sleeping, remember your troubadour; because now I understand .. .I'm grasping the human equation of your love. It thunders on the mystic dulcimer, the gem stormy and treacherous, the witchery of your "yes." Moreover, it falls, the downpour falls on the coffin of my path, where I gnaw my bones for you ... Cesar Vallejo: The Black Heralds Je voudrais que mon amour meure Samuel Beckett Bản tiếng Anh của chính

tác giả: I would like my love to die Bản của Gấu: Gấu muốn tình Gấu chết,

John Montague, ngưòi điểm tập

thơ, cũng là bạn của Beckett, có 1 lý thuyết [an almost-theory], về Beckett

làm thơ: Thay vì cố gắng làm thơ mới, Beckett trải qua hầu hết thì giờ

để dịch thơ của ông, một việc làm mà chính ông than, nặng quá,

đếch chịu nổi, a burden he often found intolerable. Samuel Beckett

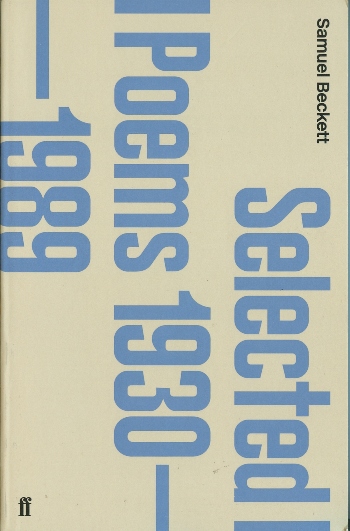

Although approved by Beckett, these lost

translations of "Mirlitonnades" (Doggerels) have never been published,

until now. We are grateful to Grove Press for allowing us to reprint the originals here. [The Paris Review Winter 2015] DOGGERELS

vive rnorte ma seule saison lis blancs chrysanthèmes nids vifs abandonnés boue des feuilles d'avril beaux jours gris de givre alive dead only season mine white lilies feverfews vivid nests forsaken silt of April leaves frost fair hoar grey days ce qu'ont les yeux mal vu de bien les doigts laissé de bien filer serre-les bien les doigts les yeux le bien revient en mieux what good the eyes have ill seen good the fingers have let escape close them tight the fingers the eyes good is back better still ce qu'a de pis le coeur connu la tête pu de pis se dire fais-les ressusciter le pis revient en pire what worse the heart has known worse the head to itself said make them resuscitate worse is back worst still le nain nonagénaire dans un dernier murmure de grâce au moins une bière grandeur nature the dwarf in his last nonagenarian gasp for mercy's sake at least a full-size coffin fous qui disiez plus jamais vite redites fools who said nevermore quick say it again pas davantage de souvenirs qu'à l’âge d'avril un jour d'un jour no more memories than at the age of April one day of a day - Translated from the French by Edith Fournier Beckett có 1 từ, ông chuyển từ tiếng Pháp qua tiếng Anh, nhưng khi chuyển lại tiếng Tẩy, thì từ gốc không xứng với nó. Trên TV có từ thần sầu này, nhưng không làm sao kiếm. Bài thơ trên đây, tuy được tác giả gật đầu OK, nhưng bây giờ kiếm thấy, và đây là lần in thứ nhất của nó. (1) Có nhiều câu đúng điệu Beckett, “nửa đêm, mưa, tớ về nhà, không phải nửa đêm, không phải mưa.” Khi ông mới xuất hiện, gần như chẳng ai chịu nổi thứ văn này, nhưng bây giờ thì quá tuyệt Sống chết mùa độc nhất của tớ Huệ trắng Tổ chim sặc sỡ bỏ hoang Mùn lá tháng Tư Ngày đẹp xám màu sương giá (1). Sự thực, không đúng như tờ Paris Review. Bài thơ chưa từng in ấn này, đã xuất hiện, trong Selected Poems 1930-1989, nhưng chỉ có khổ đầu. NQT Bài này, cũng tuyệt, trong Selected Poems 1930-1989 A perte de vue dans le sens de mon corps

Tous les arbres toutes leurs branches toutes leurs feuilles L'herbe à la base les rochers et les maisons en masse Au loin la mer que ton oeil baigne Ces images d'un jour après l'autre Les vices les vertus tellement imparfaits La transparence des passants dans les rues de hasard Et les passantes exhalées par tes recherches obstinées Tes idées fixes au cceur de plomb aux lèvres vierges Les vices les vertus tellement imparfaits La ressemblance des regards de permission avec les yeux que tu conquis La confusion des corps des lassitudes des ardeurs L'imitation des mots des attitudes des idées Les vices les vertus tellement imparfaits L'amour c'est l'homme inachevé, Out of Sight in the Direction of My Body

All the trees all their boughs all their leaves The grass at the base the rocks the massed houses Mar the sea that thine eye washes Those images of one day and the next The vices the virtues that are so imperfect The transparence of men that pass in the streets of hazard And women that pass in a fume from thy dour questing The fixed ideas virgin-lipped leaden-hearted The vices the virtues that are so imperfect The eyes consenting resembling the eyes thou didst vanquish The confusion of the bodies the lassitudes the ardours The imitation of the words the attitudes the ideas The vices the virtues that are so imperfect Love is man unfinished.

I knew if you had died that I should grieve Yet I found my heart wishing you were dead. Tôi biết nếu bạn chết tôi sẽ đau khổ Vậy mà thâm tâm tôi lại mong điều đó. Bài thơ không đề của Beckett, là từ hai câu thơ trên, của bạn ông. Bài thơ trên, lần đầu Gấu đọc, là ở trong Thơ ở đâu xa của TTT. Nhưng, thú vị nhất, hay đúng hơn, thê lương nhất, lại là cái tít của bài viết của Tolbin. Về những năm tháng thê thảm của Beckett, thời kỳ 1930-1936, Tolbin viết: Vấn đề của ông trong những năm này xem ra thật dễ, nhưng lại khó giải quyết: it was how to live, what to do, and who to be, sống thế nào, làm cái gì, là thằng gì. Ông [Beckett] thì khôn khéo [clever], có học [well-educated], ông nói rành tiếng Anh, tiếng Ý, tiếng Đức của ông thì thật tốt. Nhưng cuốn sách đầu, truyện ngắn, của ông không bán được, và ông không làm sao kiếm được nhà xb cho tiểu thuyết của ông. Ông không biết làm cách nào kiếm sống. Rất nhiều giai thoại thật tuyệt vời về chuyện Beckett mê tranh của Jack Yeats. Tình bạn giữa ông và McGreevy là cũng từ chuyện mê tranh Yeats. je suis ce cours de sable qui glisse cher instant je te vois my way is in the sand flowing my peace is there in the receding

mist Bản tiếng Tây theo tôi tuyệt hơn

bản tiếng Anh, cũng của Beckett: Mưa

hạ mưa trên đời tôi Lại nhớ mưa Sài Gòn! http://www.theparisreview.org/current-issue

More and more, along the shore

Homecoming

Snowfall, denser and denser, dove-coloured as yesterday, snowfall, as if even now you were sleeping. White, stacked into distance. Above it, endless, the sleigh track of the lost. Below, hidden, presses up what so hurts the eyes, hill upon hill, invisible. On each, fetched home into its (oday, an I slipped away into dumbness: wooden, a post. There: a feeling, blown across by the ice wind attaching its dove- its snow- coloured cloth as a flag. Ungeschriebenes, zu Sprach verhärtet […]

Du non-écrit, durci en langue […]

Về cái không-viết ra, cứng lại thành ngôn ngữ […]Note: Thấy, trên Gió O, Thầy Đạo cũng đang thuyết giảng về Paul Celan. Ông này, cũng như Beckett, rất khó đọc, khó dịch, và điều kiện bắt buộc, phải giỏi/quen/ rất thành thạo, khi sử dụng tiếng Mít. Câu trên, từ hỏng nhất, là thành, thành ngôn ngữ. en langue, trong tiếng nói, trong ngôn ngữ, mới đúng. GCC dịch, về cái không viết, cứng rắn, trong ngôn ngữ. Gấu nghi, Thầy thuyết giảng, nhưng cũng không tin tưởng cho lắm, có người thực sự đọc! Thơ Mỗi Ngày Một vị độc giả, GCC nghi là Thầy

Đạo, trả lời, theo kiểu ẩn danh:

Durcir en: cứng rắn thành, và thêm, mi dốt tiếng Tây quá, mà cũng bày đặt! NQT Cái chuyện dốt tiếng Tây, thì tất nhiên, đâu phải tiếng Mít. Trên talawas, 1 vị độc giả đã từng lôi những chỗ thầy Đạo dịch sai, mà sai thật, Thầy đếch thèm trả lời. Thầy thua… GCC ở chỗ đó. Trên TV, bất cứ trường hợp nào dịch sai, được độc giả chỉ cho thấy, thì đều có phúc đáp, có cám ơn. Trường hợp ở đây, cũng vậy. Thầy có thể thẳng thắn trả lời, durcir đi với en, cứng rắn thành. Có sao đâu. Theo GCC, "trong" hợp lý hơn "thành". Đây là giới từ, khi chuyển qua tiếng Việt, sử dụng từ nào hợp lý nhất, là tuỳ người dịch. Lần gặp Thầy Đạo, lần đầu qua Cali, 1998, ở tiệm sách VK, của DDT, ở Tiểu Sài Gòn, Thầy rất bực khi GCC không nhớ ra Thầy. Người phán, mi không nhớ ta sao, ta đã từng đi tới nhà mi, khi còn ở hẻm Đội Có, Phú Nhuận, cùng với ông anh của BHD. Ông nói thì Gấu nhớ mang máng đã từng gặp, như thế thực. Và nếu như thế, thì ông học sau GCC. Khi ở hẻm Đội Có, là Gấu được Bà Trẻ đem về nuôi, đã xong hai cái bằng Tú Tài, đang học Toán Đại Cương. Do không có tiền mua sách, ngoài cái cours quay ronéo, cuối năm, đi thi, chẳng hiểu cái đầu bài toán thi đó, nó là cái gì, GCC bỏ phòng thi ra về. Liền sau đó, thấy báo loan tin Ty Cảnh Sát Gia Định tuyển biên tập viên, Gấu bèn nạp liền, nhận liền, vì dễ có ai có cả hai cái bằng Tú Tài như Gấu. Về khoe với Bà Trẻ, hết đói rồi, Bà mắng, mi đến lấy ngay cái đơn, xé bỏ, gia đình nhà mi không có mả đánh người! Truyện này kể rồi, nhưng quả là nó ám Gấu cả đời. Nếu như thế, thì đó cũng là lần đầu tiên, Gấu biết đến ông anh của BHD. Ông vô thăm 1 người bạn ở trong hẻm, không phải GCC. Sau đó, đọc tin Trường Quốc Gia Bưu Điện mới thành lập, mở kỳ thi lấy sinh viên, học hai năm, thay vì ba năm, điều kiện phải có bằng Tú Tài Hai. Gấu thi, đậu, nhưng không đi học, vì chê, ra trường, lương chỉ số 350, chỉ số lương Cán Sự, vẫn còn nhớ, thua, nếu ra trường Đại Học Sư Phạm, lương kỹ sư! Bỏ Toán Đại Cương, qua học Toán Lý Hóa, MPC, cuối năm, thi rớt. Cái sự thi rớt này, cũng là do quá kiêu ngạo mà ra. Hình như cũng đã kể ra rồi. Đến Bưu Điện, lấy lại cái hồ sơ, trong có cái bản sao chứng chỉ Tú Tài Hai, vì tiền đâu mà lại đi sao 1 bản khác nữa, ông thầy giám thị biểu Gấu, mi ngu quá, nghèo như mi, thì sao không học Bưu Điện cho xong đi, rồi đi làm, rồi có tiền, muốn học gì thì học. Gấu nghe bùi tai quá, bèn nói, nhưng em bỏ mất 1 năm học rồi, làm sao học. Ông nói, để ta nói với Thầy hiệu trưởng. Thầy Trần Văn Viễn. Ông gọi vô, hỏi, năm rồi, mi học đâu, em - học sinh Miền Nam, thưa thầy, em, khác Bắc Kít, thưa thầy, con - học MPC. Ông bèn lôi tới cái bảng đen, ra ngay 1 bài toán, Gấu giải như máy - thực sự là thế - Thầy rất mừng, bèn gật đầu, cho vô học năm thứ nhì. Vẫn còn nhớ, khi học, Gấu có thói quen, gác chân lên cái ghế trống phía trước, và bị 1 ông Thầy, kỹ sư Tuân, cũng từ Pháp về cùng 1 đợt với Thầy Viễn, bực lắm, nhưng Thầy lại không nói ra, nhưng Gấu biết, Thầy không ưa Gấu, nên khi ra trường, học cours của Thầy thật là kỹ. Đến kỳ thi, bài thi của Thầy, Gấu không làm được, vì nó thuộc phần học quá dễ, Gấu bỏ qua, vì nghĩ trong bụng, ông Thầy này không ưa ta, chắc là ra bài thực khó. Thế là ông đánh rớt. Thầy Viễn biết, bèn hỏi, Thầy Tuân nói, tôi hỏi nó 1 câu thật dễ, nó không trả lời được, Thầy Viễn cười, anh hỏi nó 1 câu thật khó, mới đúng, vì nó, nhất trong mấy đứa đó! Ui chao, Thầy quá thương, quá hiểu trò! Cái tính cực kỳ kiêu ngạo của Gấu Cà Chớn, là do cái sự Gấu cực kỳ giỏi về Toán, mà ra! Hà, hà! Mấy đứa cháu, cháu ngoại, như Jennifer, thằng Lùn Richie, cũng giỏi Toán. Jennifer đi thi toán, toàn liên bang Canada, về nhì! Cái sự thù hằn của Thầy Đạo với GCC, nếu có, thì thực là quái dị, vì Gấu có bao giờ đọc ông đâu, và ông có viết cái gì đâu mà đọc? Thấy ông khoe, ông đã từng viết cho Sáng Tạo, và nếu như thế, thì còn là đàn anh của Gấu. Lần đầu tiên Gấu biết tới ông, là lần ông viết trên talawas, tố Gấu với em Sến, Bắc Kít, là tên đó không phải dân khoa bảng! Cũng là lần ông tố Thầy của ông ta, là Nguyễn Văn Trung, thuổng 1 bài viết cùa 1 tên Tây mũi lõ! Những sự kiện này, trên talawas,chắc là vẫn còn. Luôn cả bài viết của 1 độc giả chê Thầy Đạo dịch sai tiếng Tẩy, khi đọc Linda Lê. (1) (1) Margaret Nguyen Linda Lê viết: «Mon père apparaît, disparaît entre les ruines. Je suis sa trace» Đào Trung Đạo dịch: «Cha tôi xuất hiện rồi biến mất giữa những đống đổ nát. Tôi là dấu vết của ông». Một câu ngây ngô! Chỉ con nít đang học chia động từ «être» thì mới nhắc lại như vẹt rằng «je suis - tôi là, tu es - anh là, il est – nó là...». «Suis» ở trong câu của Linda Lê phải được hiểu là động từ «suivre» - «đi theo». Tóm lại, câu trên phải dịch đơn giản như vầy: «… Tôi đi theo dấu vết của ông». Nhật ký Tin Văn Theo GCC, ngay khi đọc được/được đọc, 1 độc giả, sửa cho mình 1 cái lỗi dịch sai như trên, là phải đi 1 cái mail, gửi "em" Sến, xin cho đăng 1 lời cảm ơn người sửa sai cho mình rồi. Thầy Đạo, vờ. Chính là từ cái sự vờ này, ra điều mà Brodsky phán, mỹ là mẹ của đạo hạnh, và từ đó, ra câu của Dos, cái đẹp sẽ cứu chuộc thế giới, [chứ không đạo hạnh], và ra câu của Roland Barthes, khi ông hiểu ra được ý của Kafka, khi Kafka cho rằng, kỹ thuật là hữu thể, être, being, của văn chương. Viết như thế nào, how, chứ không phải tại sao, why, viết. Không đơn giản đâu, cái sự vờ này! Tếu nhất, thiếu “mỹ” nhất, là cái vụ Thầy điểm sách của 1 tên mũi lõ, và ông này mail “phúc đáp”. Thầy kể là ông này cũng triết gia, thế là hai bên nói chuyện tương đắc lắm. Hóa ra không phải vậy, vì bà chủ báo sau đó, cho công bố cái mail của vị độc giả. Ông ta cằn nhằn, viết về sách của tôi, mà để cái hình 1 tay dịch, sách của tôi! Cú này, ThảoTrường bị rồi. Ông được 1 website của 1 nhà văn Mít hải ngoại, vì mục đích bảo tồn nọc độc văn hóa Mỹ Ngụy, đưa lên trang của ông. Cái trang này, lâu quá quên tên, bạn vô, có thể đọc, nhưng không thể copy. Có điều, ông ta lầm hình Thảo Trường, với 1 ông khác, hình như là Thế Uyên. Thảo Trường biểu Gấu, ông rành ba cái web wiếc, ông làm ơn nói, sửa giùm. (1) Một bữa Hai Lúa trong khi bay lượn trên không gian ảo, tình cờ lạc vô trang VHNT, của Nguyễn Ý Thuần. Ông là một trong những nhà văn đã từng được nhà phê bình lớn và còn là học giả ở trong nước, là Hoàng Ngọc Hiến, nhắc tới, suýt soa, đây là thứ văn chương vượt lằn ranh Quốc Cộng, tới cõi nhân bản... [Xin xem bài của HNH viết về VHHN]. Thú thực, đó là lần đầu tiên, Hai Lúa biết tới tên ông NYT này. Coi sơ sơ, tới mục giới thiệu những nhà văn tác phẩm của họ, HL thấy tên nhà văn Thảo Trường. Ông này HL quá quen, nhưng ơ kìa, nhìn hình kìa, không phải là ông Thảo Trường từ xưa tới giờ. Đọc tác phẩm thì đúng là ổng, nhưng hình không phải ổng. Thế rồi bận bịu, quên luôn, cho tới một bữa ông TT viết mail, này, ông Gấu [xin lỗi bà Gấu phải lập lại từ này], tôi nghe nói, có ai đó post tác phẩm, hình, tiểu sử của tôi, nhưng hình thì không phải. Tôi không quen sử dụng net, phiền ông liên lạc giùm. Hai Lúa bèn mail cho nhà văn lớn Nguyễn Ý Thuần, nói rõ câu chuyện, lại còn đề nghị, nếu cần hình nhà văn mập TT, sẽ sẵn sàng mail tới. Đếch thèm trả lời. Nhưng coi lại, hình của nhà văn mập đã được hạ xuống!

PAUL ELUARD

L’amoureuse Elle est debout sur mes paupières Et ses cheveux sont dans les miens, Elle a la forme de mes mains, Elle a la couleur de mes yeux, Elle s'engloutit dans mon ombre Comme une pierre sur le ciel. Elle a toujours les yeux ouverts Et ne me laisse pas dormir. Ses rêves en pleine lumière Font s'évaporer les soleils, Me font rire, pleurer et rire, Parler sans avoir rien à dire. Lady Love

She is standing on my lids And her hair is in my hair, She has the colour of my eye, She has the body of my hand, In my shade she is engulfed As a stone against the sky. She will never close her eyes And she does not let me sleep. And her dreams in the bright day Make the suns evaporate, And me laugh cry and laugh, Speak when I have nothing to say. Samuel Beckett: Selected Poems 1930-1989 Nàng Yêu

Nàng đứng trên mi tôiTóc nàng trong tóc tôi Dáng nàng trong tay tôi Màu nàng màu mắt tôi Nàng chìm vào bóng tôi Như hòn đá trên trời Mắt nàng không hề khép Đừng ngủ, đừng ngủ, Gấu Ngu ơi Và những giấc mơ của nàng đầy ánh sáng Làm mặt trời bốc hơi Làm tôi cười, khóc, rồi lại cười Nói, chẳng biết nói cái gì. ******* To think,

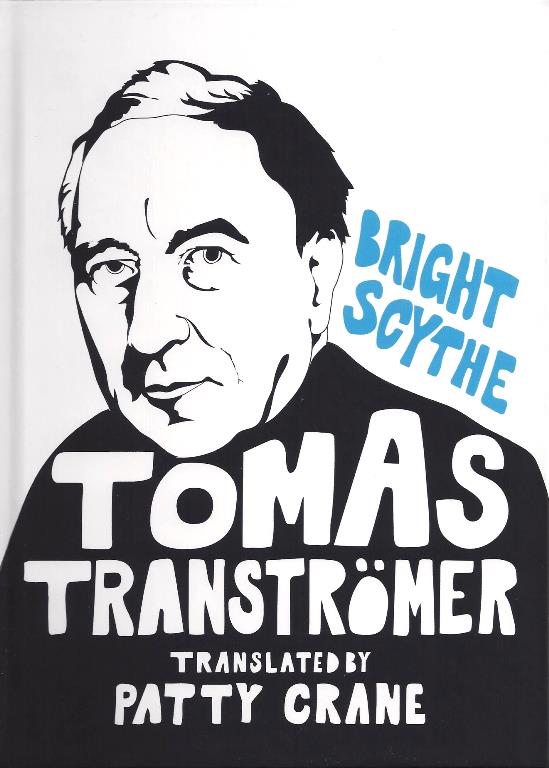

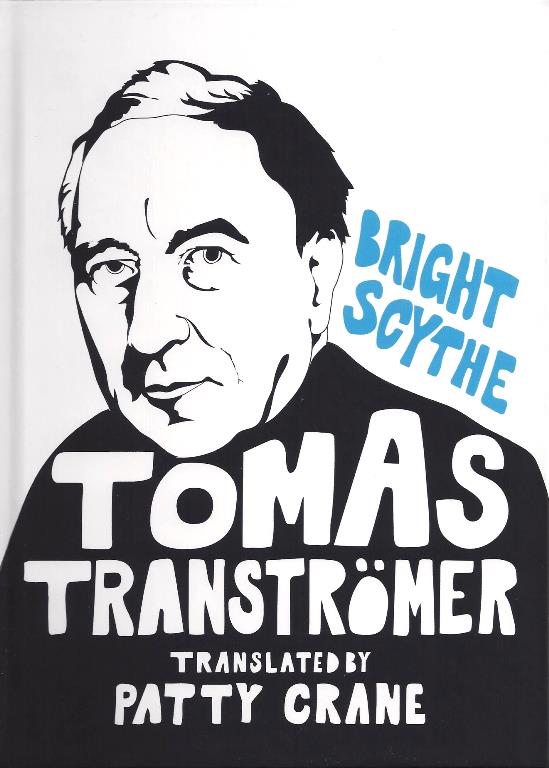

when one is no Nghĩ, khi mi không còn trẻ nữa, khi mi chưa già khằn; Rằng, mi không còn trẻ nữa; rằng mi già khằn, nhưng chưa chết hẳn Thì cũng là 1 cái gì rồi The Swedish poet you will soon

be reading Nhà thơ Thụy Ðiển sẽ được đọc rất sớm sủa. Giữa trận cá độ vào phút

chót 100/1 dành cho Bob Dylan, ở 1 nhà cái, thì đùng 1 phát, nhà thơ

ít được người đời biết tới, Tomas Tranströmer, người Thụy Ðiển,

đất nước sở tại, thắng Nobel văn chương. Thực tại là của ngôn

ngữ, tiết kiệm là của nhà thơ. Brodsky (1) Anh Gấu tối ngày mua sách-bỏ-túi để đọc

mà sao dịch "ngộ" rứa ? Tks & Take Care & Happy New Year GCC

Note: Ông này là 1 trong

những dịch giả thơ TT, và là tác giả bài viết Translating Tomas Tranströmer, Dịch TT Gấu tính dịch bài thơ

trên, và giữ nguyên cái form của nó trên tờ báo, thay vì scan. Bài thơ của Gấu cũng có hải âu,

cũng có tiếng thì thầm của hải âu, của Gấu, và của biển

Trên net, tờ Người Kinh Tế có bài viết về Nobel

văn chương năm nay của Prospero. Cái chi tiết thần kỳ mà Prospero

khui ra từ thơ của Tomas Transtromer, [the Swedish Academy has praised an

oeuvre that is “characterised by economy”], làm GCC nhớ tới Brodsky, qua

đoạn viết sau đây: Bài

thơ đâu khác chi một giấc mơ khắc khoải, trong đó bạn có được một

cái chi cực kỳ quí giá: chỉ để mất tức thì. Trong giấc hoàng lương ngắn

ngủi, hoặc có lẽ chính vì ngắn ngủi, cho nên những giấc mơ như thế

có tính thuyết phục đến từng chi tiết. Một bài thơ, như định nghĩa,

cũng giới hạn như vậy. Cả hai đều là dồn nén, chỉ khác, bài thơ, vốn

là một hành vi ý thức, không phải sự phô diễn rông dài hoặc ẩn dụ

về thực tại, nhưng nó chính là thực tại. Nobel prize for literature The Swedish poet you will soon be reading

Oct 6th 2011, 18:43 AMID the flurry of last-minute

bets for Bob Dylan (once rated by bookies at 100/1), a relatively

unknown Swedish poet, Tomas Tranströmer, has won the Nobel prize

for literature. “He is a poet but has never really been a full-time

writer,” explained Peter Englund, the permanent secretary of the Swedish

Academy, which decides the award. Though Mr Tranströmer has not written

much lately, since suffering from a stroke in 1990 that left him partly

paralysed, he is beloved in Sweden, where his name has been mentioned

for the Nobel for years. One newspaper photographer has been standing

outside his door on the day of the announcement for the last decade, anticipating

this moment. Tomas Tranströmer – My Nobel prize-winning

hero The literature prize means the world of poetry can finally raise a glass to salute this humble man

Nguyên tác tiếng Anh: Tranströmer's

surreal explorations

of the inner world and its relation to the jagged landscape of his native

country have been translated into over 50 languages. GCC dịch: Những thám

hiểm siêu thực [TQ bỏ từ này] thế giới nội tại, và sự tương

quan của nó [số ít, không phải

những tương quan] với những phong cảnh lởm chởm [TQ bỏ từ này

luôn] của quê hương của ông được dịch ra trên 50 thứ tiếng. Mấy từ quan trọng, TQ đều bỏ, chán thế. Chỉ nội 1 từ “lởm chởm” bỏ đi,

là mất mẹ 1 nửa cõi thơ của ông này rồi. Chứng cớ: The landscape of Tranströmer's

poetry has remained constant during his 50-year career: the jagged

coastland of his native Sweden, with its dark spruce and pine forests,

sudden light and sudden storm, restless seas and endless winters,

is mirrored by his direct, plain-speaking style and arresting, unforgettable

images. Sometimes referred to as a "buzzard poet", Tranströmer seems

to hang over this landscape with a gimlet eye that sees the world with

an almost mystical precision. A view that first appeared open and featureless

now holds an anxiety of detail; the voice that first sounded spare and

simple now seems subtle, shrewd and thrillingly intimate. [Phong cảnh thơ TT thì

thường hằng trong 50 năm hành nghề thơ: miền đất ven biển lởm chởm

của quê hương Thụy Ðiển với những rừng cây thông, vân sam u tối,

chớp bão bất thần, biển không ngừng cựa quậy và những mùa đông dài

lê thê, chẳng chịu chấm dứt, phong cảnh đó được phản chiếu vào thơ

của ông, bằng 1 thứ văn phong thẳng tuột và những hình ảnh lôi

cuốn, không thể nào quên được. Thường được nhắc tới qua cái nick “nhà

thơ buzzard, chim ó”, Transtromer như treo lơ lửng bên trên phong cảnh

đó với con mắt gimlet [dây câu bện thép], nhìn thế giới với 1 sự chính

xác hầu như huyền bí, thần kỳ. Một cái nhìn thoạt đầu có vẻ phơi

mở, không nét đặc biệt, và rồi thì nắm giữ một cách âu lo sao xuyến

chi tiết sự kiện, tiếng thơ lúc đầu có vẻ thanh đạm, sơ sài, và rồi

thì thật chi li, tế nhị, sắc sảo, và rất ư là riêng tư, thân mật đến

ngỡ ngàng, đến sững sờ, đến nghẹt thở.] Chỉ đến khi ngộ ra cõi thơ, thì Gấu mới hiểu ra là, 1 Nobel văn chương về tay 1 nhà thơ là 1 cơ hội tuyệt vời nhất trong đời một người… mê thơ. Người ta thường nói, thời của anh mà không đọc Dos, đọc Kafka… thí dụ, là vứt đi, nhưng không được nhìn thấy 1 nhà thơ được vinh danh Nobel thì quả là 1 đại bất hạnh!Hà, hà!

Thí dụ, bài Lament. LAMENTO

He put the pen down.It lies there without moving. It lies there without moving in empty space. He put the pen down. So much that can neither be written nor kept inside! His body, is stiffened by something happening far away though the curious overnight bag beats like a heart. Outside, the late spring. From the foliage a whistling-people or birds? And the cherry trees in bloom pat the heavy trucks on the way home. Weeks go by. Slowly night comes. Moths settle down on the pane: small pale telegrams from the world. Tomas Transtromer: Selected Poems [ed by Robert Hass] LAMENT

He laid down his pen. It rests quietly on the table. It rests quietly in the void. He laid down his pen. Too much that can neither be written nor kept inside! He's paralyzed by something happening far away although his marvelous travel bag pulses like a heart. Outside, it's early summer. From the greenness comes whistling-people or birds? And blossoming cherry trees embrace the trucks that have returned home. Weeks go by. Night arrives slowly. Moths settle on the windowpane: small pale telegrams from the world. Patty Crane: Bright Scythe Ghi chú về 1 giọng văn: Woolf

Favourite trick

Ventriloquism. Woolf was an exponent of the “free indirect

style”, whereby the narrator inhabits the voice of the character.

In “Mrs Dalloway”, for instance, the following lines are attributed

to the narrator, but they are unmistakably Clarissa’s thoughts:

“Hugh’s socks were without exception the most beautiful she had

ever seen — and now his evening dress. Perfect!” As J. Hillis Miller

put it, the narrator is a function of the character’s thoughts in Woolf’s

writing, not the other way around – “they think therefore I am.”

Mánh thần sầu. Nói bằng bụng. Ui chao, bèn nhớ đến Kim Dung. Đúng hơn, Kiều Phong, trong trận đấu kinh hồn lạc phách ở Tụ Hiền Trang. Kiều Phong mang A Châu tới, năn nỉ Tiết Thần Y trị thương cho nàng, sau khi trúng đòn của Kiều Phong. Mãnh hổ Nam Kít [Khất Đan] địch quần hồ Bắc Kít [Trung Nguyên]... May được vị đại hán mặc đồ đen cứu thoát. Trước khi bỏ đi, bèn tát cho KP 1 phát, và chửi, tại sao mi ngu thế, chết vì 1 đứa con gái xa lạ, không quen biết. Ui chao, lại Ui chao, đây là đòn phục bút, để sửa soạn cho cú tái ngộ Nhạn Môn Quan, Kiều Phong tung A Châu lên trời, như con gà con, chờ rớt xuống, ôm chặt vào lòng, hai ta ra quan ngoại chăn dê, sống đời tuyệt tích, không thèm dính vô chốn giang hồ gió tanh mưa máu… Trong đời KP, hai lần đánh xém chết người đẹp, hai chị em sinh đôi, đều yêu ông, tếu thế. Lần đánh A Châu, được Tiết Thần Y cứu, lần đánh A Tử, nhờ đó, tìm lại được xứ Nam Kít của ông, rồi chết vì nó… Ui chao, lại nhớ Sến. Em chửi - mắng yêu, đúng hơn - sao ngu thế, mất thì giờ với tiểu thuyết chưởng! Nhắc tới Kiều Phong, ở đây, là do trong trận Tụ Hiền Trang, có 1 tên đệ tử của Tinh Tú Lão Quái, dùng môn "nói bằng bụng" chọc quê KP, bị KP quát 1 phát, bể bụng chết tươi, hà hà! Môn võ công này, hễ gặp tay nội công cao hơn, là bỏ mẹ!

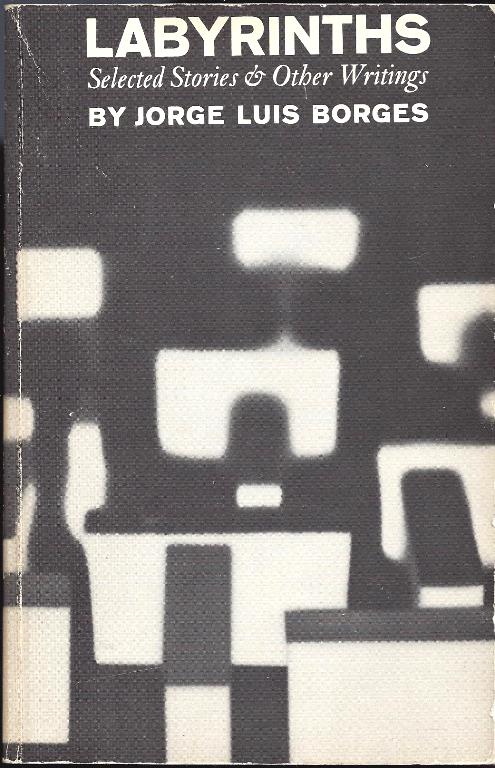

Mê Cung Note: Cuốn này, GCC có bản tiếng Tây, và,

tất nhiên, có nguyên tác tiếng Tẩy, bài Tựa của Maurois. Nhưng kiếm hoài

không thấy, trong kho sách khổng lồ, nơi bên dưới cầu thang. May mà

kiếm thấy bản tiếng Anh.

Thôi đành post bản tiếng Anh vậy. Maurois coi Borges "đã từng", was, là đệ tử trực tiếp của Kafka, và “Lâu Đài”, có thể do Borges, nhưng nếu là ông, nó sẽ chỉ còn chừng vài trang, do lười và không ưa sự toàn hảo. [Kafka was a direct precursor of Borges. The Castle might be by Borges, but he would have made it into a ten-page story, both out of lofty laziness and out of concern for perfection.] Gấu đã từng nhận ra điều này, đúng như thế, và cũng đã từng viết ra đâu đó, trên TV. Nhưng có 1 khoảng cách xa vời vợi giữa họ, như giữa mộng và thực. Với Kafka, Lâu Đài là thực, tức thế giới toàn trị. Preface

Jorge Luis Borges is a great writer who has composed only little essays or short narratives. Yet they suffice for us to call him great because of their wonderful intelligence, their wealth of invention, and their tight, almost mathematical, style. Argentine by birth and temperament, but nurtured on universal literature, Borges has no spiritual homeland. He creates, outside time and space, imaginary and symbolic worlds. It is a sign of his importance that, in placing him, only strange and perfect works can be called to mind. He is akin to Kafka, Poe, sometimes to Henry James and Wells, always to Valery by the abrupt projection of his paradoxes in what has been called "his private metaphysics." I

His sources are innumerable and unexpected. Borges has read

everything, and especially what nobody reads any more: the Cabalists,

the Alexandrine Greeks, medieval philosophers. His erudition is not

profound-he asks of it only flashes of lightning and ideas-but it is

vast. For example, Pascal wrote: "Nature is an infinite sphere whose

center is everywhere, whose circumference is nowhere." Borges sets out

to hunt down this metaphor through the centuries. He finds in Giordano

Bruno (1584): "We can assert with certainty that the universe is all

center, or that the center of the universe is everywhere and its circumference

nowhere." But Giordano Bruno had been able to read in a twelfth-century

French theologian, Alain de Lille, a formulation borrowed from the Corpus

Hermeticum (third century): "God is an intelligible sphere whose center

is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere," Such researches, carried

out among the Chinese as among the Arabs or the Egyptians, delight Borges,

and lead him to the subjects of his stories.Many of his masters are English, He has an infinite admiration for Wells and is indignant that Oscar Wilde could define him as "a scientific Jules Verne," Borges makes the observation that the fiction of Jules Verne speculates on future probability (the submarine, the trip to the moon), that of Wells on pure possibility (an invisible man, a flower that devours a man, a machine to explore time), or even on impossibility (a man returning from the hereafter with a future flower). Beyond that, a Wells novel symbolically represents features inherent in all human destinies. Any great and lasting book must be ambiguous, Borges says; it is a mirror that makes the reader's features known, but the author must seem to be unaware of the significance of his work-which is an excellent description of Borges's own art. "God must not engage in theology; the writer must not destroy by human reasonings the faith that art requires of us." He admires Poe and Chesterton as much as he does Wells. Poe wrote perfect tales of fantastic horror and invented the detective story, but he never combined the two types of writing. Chesterton did attempt and felicitously brought off this tour de force. Each of Father Brown's adventures proposes to explain, in reason's name, an unexplainable fact. "Though Chesterton disclaimed being a Poe or Kafka, there was, in the material out of which his ego was molded, something that tended to nightmare." Kafka was a direct precursor of Borges. The Castle might be by Borges, but he would have made it into a ten-page story, both out of lofty laziness and out of concern for perfection. As for Kafka's precursors, Borges's erudition takes pleasure in finding them in Zeno of Elea, Kierkegaard and Robert Browning. In each of these authors there is some Kafka, but if Kafka had not written, nobody would have been able to notice it-whence this very Borgesian paradox: "Every writer creates his own precursors." Another man who inspires him is the English writer John William Dunne, author of such curious books about time, in which he claims that the past, present and future exist simultaneously, as is proved by our dreams. (Schopenhauer, Borges remarks, had already written that life and dreams are leaves of the same book: reading them in order is living; skimming through them is dreaming.) In death we shall rediscover all the instants of our life and we shall freely combine them as in dreams. "God, our friends, and Shakespeare will collaborate with us." Nothing pleases Borges better than to play in this way with mind, dreams, space and time. The more complicated the game becomes, the happier he is. The dreamer can be dreamed in his turn. "The Mind was dreaming; the world was its dream." In all philosophers, from Democritus to Spinoza, from Schopenhauer to Kierkegaard, he is on the watch for paradoxical intellectual possibilities. II

There are to be found in Valery's notebooks many notes such

as this: "Idea for a frightening story: it is discovered that the

only remedy for cancer is living human flesh. Consequences." I can well

imagine a piece of Borges "fiction" written on such a theme. Reading

ancient and modern philosophers, he stops at an idea or a hypothesis.

The spark flashes. "If this absurd postulate were developed to its extreme

logical consequences," he wonders, "what world would be created?" For example, an author, Pierre Menard, undertakes to compose Don Quixote-not another Quixote, but the Quixote. His method? To know Spanish well, to rediscover the Catholic faith, to war against the Moors, to forget the history of Europe-in short, to be Miguel de Cervantes. The coincidence then becomes so total that the twentieth-century author rewrites Cervantes' novel literally, word for word, and without referring to the original. And here Borges has this astonishing sentence: "The text of Cervantes and that of Menard are verbally identical, but the second is almost infinitely richer." This he triumphantly demonstrates, for this subject, apparently absurd, in fact expresses a real idea: the Quixote that we read is not that of Cervantes, any more than our Madame Bovary is that of Flaubert. Each twentieth-century reader involuntarily rewrites in his own way the masterpieces of past centuries. It was enough to make an extrapolation in order to draw Borges's story out of it. Often a paradox that ought to bowl us over does not strike us in the abstract form given it by philosophers. Borges makes a concrete reality out of it. The "Library of Babel" is the image of the universe, infinite and always started over again. Most of the books in this library are unintelligible, letters thrown together by chance or perversely repeated, but sometimes, in this labyrinth of letters, a reasonable line or sentence is found. Such are the laws of nature, tiny cases of regularity in a chaotic world. The "Lottery in Babylon" is another ingenious and penetrating staging of the role of chance in life. The mysterious Company that distributes good and bad luck reminds us of the "musical banks" in Samuel Butler's Erewhon. Attracted by metaphysics, but accepting no system as true, Borges makes out of all of them a game for the mind. He discovers two tendencies in himself: "one to esteem religious and philosophical ideas for their aesthetic value, and even for what is magical or marvelous in their content. That is perhaps the indication of an essential skepticism. The other is to suppose in advance that the quantity of fables or metaphors of which man's imagination is capable is limited, but that this small number of inventions can be everything to everyone." Among these fables or ideas, certain ones -particularly fascinate him: that of Endless Recurrence, or the circular repetition of all the history of the world, a theme dear to Nietzsche; that of the dream within a dream; that of centuries that seem minutes and seconds that seem years ("The Secret Miracle"); that of the hallucinatory nature of the world. He likes to quote Novalis: "The greatest of sorcerers would be the one who would cast a spell on himself to the degree of taking his own phantasmagoria for autonomous apparitions. Might that not be our case?" Borges answers that indeed it is our case: it is we who have dreamed the universe. We can see in what it consists, the deliberately constructed interplay of the mirrors and mazes of this thought, difficult but always acute and laden with secrets. In all these stories we find roads that fork, corridors that lead nowhere, except to other' corridors, and so on as far as the eye can see. For Borges this is an image of human thought, which endlessly makes its way through concatenations of causes and effects without ever exhausting infinity, and marvels over what is perhaps only inhuman chance. And why wander in these labyrinths? Once more, for aesthetic reasons; because this present infinity, these "vertiginous symmetries," have their tragic beauty. The form is more important than the content. III

Borges's form often recalls Swift's: the same gravity amid

the absurd, the same precision of detail. To demonstrate an impossible

discovery, he will adopt the tone of the most scrupulous scholar, mix

imaginary writings in with real and erudite sources. Rather than write

a whole book, which would bore him, he analyzes a book which has never

existed. "Why take five hundred pages," he asks, "to develop an idea whose

oral demonstration fits into a few minutes?" Such is, for example, the narrative that bears this bizarre title: "Tlon, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius." This concerns the history of an unknown planet, complete "with its architectures and quarrels, with the terror of its mythologies and the uproar of its languages, its emperors and seas, its minerals and birds and fish, its algebra and fire, its theological and metaphysical controversies." This invention of a new world appears to be the work of a secret society of astronomers, engineers, biologists, metaphysicians and geometricians. This world that they have created, Tlon, is a Berekeleyan and Kierkegaardian world where only inner life exists. On Tlon everyone has his own truth; external objects are whatever each one wants. The international press broadcasts this discovery, and very soon the world of Tlon obliterates our world. An imaginary past takes the place of our own. A group of solitary scientists has transformed the universe. All this is mad, subtle, and gives food for endless thought. Other stories by Borges are parables, mysterious and never explicit; still others are detective narratives in the manner of Chesterton. Their plots remain entirely intellectual. The criminal exploits his familiarity with the methods of the detective. It is Dupin against Dupin or Maigret against Maigret. One of these pieces of "fiction" is the insatiable search for a person through the scarcely perceptible reflections that he has left on other souls. In another, because a condemned man has noticed that expectations never coincide with reality, he imagines the circumstances of his own death. Since they have thus become expectations, they can no longer become realities. These inventions are described in a pure and scholarly style which must be linked up with Poe, "who begat Baudelaire, who begat Mallarme, who begat Valery," who begat Borges. It is especially by his rigor that he reminds us of Valery. "To be in love is to create a religion whose god is fallible." By his piled-up imperfects he sometimes recalls Flaubert; by the rarity of his adjectives, St. John Perse. "The inconsolable cry of a bird." But, once these relationships are pointed out, it must be said that Borges's style is, like his thought, highly original. Of the metaphysicians of Tlon he writes: "They seek neither truth nor likelihood; they seek astonishment. They think metaphysics is a branch of the literature of fantasy." That rather well defines the greatness and the art of Borges. ANDRE MAUROIS of the French Academy Translated by Sherry Mangan

THE FORGOTTEN CAPTAIN

We have many shadows. I was on my way home one September night when Y climbed out of his grave after forty years and kept me company. At first he was completely blank, just a name but his thoughts swam faster than time ran and caught up to us. I put his eyes into my eyes and saw the war's sea. The last boat he commanded rose up from under us. Ahead and behind the Atlantic convoy crept, those who would survive and those who'd been given The Mark (invisible to all), while the sleepless hours relieved each other but never him- the life vest snug under his oilskin coat. He never came home. It was internal crying that bled him to death in a Cardiff hospital. He finally got to lie down and turn into the horizon. Tomas Transtromer: Bright Scypthe Vị thuyền trưởng bị lãng quên

Chúng ta có nhiều cái bóng. Tôi đang trên đường về nhà

Một đêm tháng Chín, thì Y Bò ra khỏi ngôi mộ của anh sau bốn chục năm Và làm bạn đường với tôi. Lúc đầu anh hoàn toàn trống trơn, ngoài cái tên Nhưng những ý nghĩ của anh bơi Nhanh hơn là thời gian chạy Và bắt kịp hai đứa chúng tôi Tôi để cặp mắt của anh vô của tôi Và nhìn thấy trận thuỷ chiến Con tầu cuối cùng anh làm thuyền trưởng dâng lên Bên dưới chúng tôi Trước và sau đoàn tầu chiến Atlantic loi ngoi Những người sẽ sống sót Hay những người được đánh dấu The Mark (vô hình đối với tất cả) Trong khi những giờ không ngủ khuây khỏa lẫn nhau Nhưng không bao giờ anh – Cái phao bảo hộ ở bên dưới cái áo khoác da dầu của anh Anh chẳng bao giờ trở về nhà Chính tiếng khóc ở bên trong anh làm anh chảy máu tới chết Ở bịnh viện Cardiff Sau cùng anh nằm xuống Và biến thành đường chân trời Đề tài lớn lao độc nhất của thơ của Transtromer,

là liminality, nghệ thuật thơ ở ngưỡng cửa, như lời giới thiệu tập

thơ nhận xét.

"Good Evening, Beautiful Deep"

The great subject of the poetry of Sweden's Tomas Transtromer sometimes seems as though it is his only subject-is liminality. He is a poet almost helplessly drawn to enter and inhabit those in-between states that form the borderlines between waking and sleeping, the conscious and the unconscious, ecstasy and terror, the public self and the interior self. Again and again his poems allude to border checkpoints, boundaries, crossroads: they teeter upon thresholds of every sort-be they the brink of sleep or the brink of death, a door about to open or a door about to close. And these thresholds are often ensorcelled places, where a stone can miraculously pass through a window and leave it undamaged; where the faces of what seem to be all of humanity suddenly appear to the speaker on a motel wall, "pushing through oblivion's white walls / to breathe, to ask for something" ("The Gallery"). Indeed, in one of his finest individual collections, called Sanningsbarriaren in its original Swedish and The Truth Barrier in most English translations, he concocts a neologism which perfectly encapsulates his lifelong fixation with the liminal. This is, I suppose, Transtromner's canny way of expressing Keats's concept of negative capability. Transtromer is certainly a man who, in Keats's memorable phrase, is "capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts:' And yet he differs from Keats insofar as he sees this state not as a goal for the poet to aspire to, but as inevitable-and inevitably anxiety-provoking. In fact, he sees this condition as our fate in contemporary society. Trong lời giới thiệu bản dịch tập thơ, David Wojahan nhắc tới ý niệm của Yeats, khả năng tiêu cực, Keats’s concept of negative capability. Và tác giả tin rằng, Transtromer đúng là người “có thể ở trong những lưỡng lự, bí hiểm, hồ nghi”, “capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts”. Nhưng khác hẳn Yeats, khi cho rằng đây là mục đích, goal, thi sĩ mong tới được, thì Transtromer coi, không thể tránh được. và đây là điều kiện, như là phần số của thi sĩ, trong xã hội đương thời. Paul Celan

A LEAF, treeless

for Bertolt Brecht:

What times are these when a conversation is almost a crime because it includes so much made explicit? Một Cái Lá, không cây

Thời nào, những thời như thế nàygửi Bertolt Brecht Khi tán gẫu là một tội Bởi là vì nó bao gồm quá nhiều điều Nhờ tán gẫu mà trở thành dứt khoát? Note: Bài thơ trên, không ngờ có trên TV

rồi,và ly kỳ hơn, còn kèm thêm 1 giai thoại về nó, chôm từ TLS:

Một LÁ, không cây,

Gửi Bertolt Brecht: Thời nào thời này Khi chuyện trò là tội ác?

Tại sao thi sĩ, Trong thời điêu đứng như thế này? Holderlin V/v u trầm phiêu lãng. Đây là nói về thi sĩ kiêm tu sĩ có nick là Tu Bụi, lèm bèm về 1 bài thơ của Tẫu, trong có hình ảnh đối sầu miên: Cuộc gặp gỡ của Gấu với Woolf, cũng tình cờ, cũng "nhiệm mầu", nhưng chưa ghê gớm như của Garcia Marquez. Ông đọc, chỉ một câu, của Woolf, trong Mrs Dalloway, mà nhìn ra, trọn cả tiến trình phân huỷ của Macondo, và định mệnh sau cùng của nó ["I saw in a flash the whole process of decomposition of Macondo and its final destiny"]. * Lần đầu, là tại một tiệm sách ở Sài Gòn, một ngày đẹp trời lang thang giữa những tiệm sách ở đường Bonnard, (1), tình cờ cầm lên cuốn Bà Dalloway, vào thời điểm mà cả thành phố và lớp trẻ của nó đã, đang, hoặc sẽ đợi cái ngày con quỉ chiến tranh gọi đến tên mình, và trong khi chờ đợi như thế, đọc Sartre, Camus, hoặc trực tiếp, hoặc gián tiếp, cuốn tiểu thuyết của Woolf thật quá lạc lõng, nhưng chỉ tới khi bạn nhập vào một ngày trong đời người đẹp, nhập vào cái giọng thầm thì, hay dùng đúng thuật ngữ của những nhà phê bình, giọng độc thoại nội tâm, dòng ý thức... là bạn biết ngay một điều, nó đây rồi, đây là đúng thứ "y" cần, nếu muốn viết khác đi, muốn thay đổi hẳn cái dòng văn học Việt Nam... Mấy ngày sau, khoe với nhà thơ đàn anh, về mấy ngày đánh vật với cuốn sách, ông gật gù, mắt lim dim như muốn chia sẻ cái sướng với thằng em, và còn dặn thêm: cậu hãy nghe "tớ", phải đọc đi đọc lại, vài lần, nhiều lần... Bonnard, hai "n", Gấu viết trật, đã sửa lại, theo bản đồ Sài Gòn xưa, Việt Nam Xưa Ghi chú về 1 giọng văn: Woolf Favourite trick Ventriloquism. Woolf was an exponent of the “free indirect style”, whereby the narrator inhabits the voice of the character. In “Mrs Dalloway”, for instance, the following lines are attributed to the narrator, but they are unmistakably Clarissa’s thoughts: “Hugh’s socks were without exception the most beautiful she had ever seen — and now his evening dress. Perfect!” As J. Hillis Miller put it, the narrator is a function of the character’s thoughts in Woolf’s writing, not the other way around – “they think therefore I am.” Mánh thần sầu. Nói bằng bụng. Ui chao, bèn nhớ đến Kim Dung. Đúng hơn, Kiều Phong, trong trận đấu kinh hồn lạc phách ở Tụ Hiền Trang. Kiều Phong mang A Châu tới, năn nỉ Tiết Thần Y trị thương cho nàng, sau khi trúng đòn của Kiều Phong. Mãnh hổ Nam Kít [Khất Đan] địch quần hồ Bắc Kít [Trung Nguyên]... May được vị đại hán mặc đồ đen cứu thoát. Trước khi bỏ đi, bèn tát cho KP 1 phát, và chửi, tại sao mi ngu thế, chết vì 1 đứa con gái xa lạ, không quen biết. Ui chao, lại Ui chao, đây là đòn phục bút, để sửa soạn cho cú tái ngộ Nhạn Môn Quan, Kiều Phong tung A Châu lên trời, như con gà con, chờ rớt xuống, ôm chặt vào lòng, hai ta ra quan ngoại chăn dê, sống đời tuyệt tích, không thèm dính vô chốn giang hồ gió tanh mưa máu… Trong đời KP, hai lần đánh xém chết người đẹp, hai chị em sinh đôi, đều yêu ông, tếu thế. Lần đánh A Châu, được Tiết Thần Y cứu, lần đánh A Tử, nhờ đó, tìm lại được xứ Nam Kít của ông, rồi chết vì nó… Ui chao, lại nhớ Sến. Em chửi, sao ngu thế, mất thì giờ với tiểu thuyết chưởng! Thơ Mỗi Ngày

Thơ Tháng Tư

Manly Tears We recall the time at school

when our treasured anthology of love poetry was seized by the class

bully. We tried to snatch it back but failed. Dusting ourselves off,

we shouted into the face of our aggressor: "There is a pleasure in poetic

pains that only poets know". We then resolved to take up boxing. If only

we'd been armed with a copy of Poems That Make Grown Men Cry

by Anthony and Ben Holden - proof that verse isn't just for sissies.

Here, 100 "real men" reveal they too can be reduced to tears by a tender

rondel, a stirring sestina. The book aims to explode apparent myths about

"gender stereotyping". According to Kate Allen, the British director

of Amnesty International, with whom the publishers have collaborated,

"we hope that this anthology will encourage boys, in particular, to

know that crying - and poetry - isn't just for girls". Some weep at its poignancy;

others at its complexity. All can be grateful for a handsome new edition

of Finnegans Wake illustrated by John Vernon Lord and now

available from the Folio Society for £99. Previous projects by the artist

include illustrated versions of The Nonsense Verse of Edward

Lear and Lewis Carroll's "The Hunting of the Snark". It seems appropriate

that the original TLS review of Finnegans Wake from May 6,1939

boggles at Joyce's "Jabberwockian form". TLS April 4, 2014 Nếu bạn ở Luân Đôn, có thể

tham dự đêm thơ này, 29 Tháng Tư 2014, Nhà Hát Thành Phố. Chúng tôi hy vọng tập thơ này sẽ khuyến khích mấy cậu thanh niên biết, khóc, và tất nhiên, thơ, không chỉ dành cho mấy em, "we hope that this anthology will encourage boys, in particular, to know that crying - and poetry - isn't just for girls".

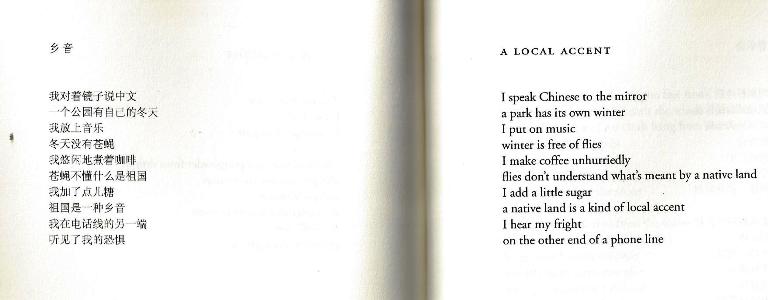

Bei Dao: The Rose

of Time

Giọng Bắc Kít

Gấu nói giọng Bắc Kít với cái

gương Ui chao, đúng là nhói 1 phát

thật, khi lần đầu gọi phôn, nghe cái giọng Bắc Kít, đúng giọng Cô Hồng

Con của 1 làng Bắc Kít, ở ven đê sông Hồng. Israeli Poems on War and Peace: Yehuda Amichai

Eyes are on the Middle East

again as we enter the holiday season. I have been browsing in a book called

After the First Rain: Israeli Poems on War and Peace (Dryad

Press), edited by Moshe Dor and Barbara Goldberg and translated by a

number of eminent American poets. It begins with a foreword by Shimon

Peres, who recalls in movingly spare and evocative language the ideals

and the assassination of his friend Yitzhak Rabin. Is all of this Cemeteries are cheap; they don't

ask for much. Is all of this sorrow? I guess

so. Yes, all of this is sorrow.

But leave This translation from the Hebrew

is by Chana Bloch. Robert Hass: Now & Then Thơ ca lớn đếch cần bước ra từ đề tài lớn, nhưng 30 Tháng Tư là một đề tài khẩn, rất khẩn, càng lâu càng trở nên khẩn! Tất cả những cái điều Gấu vừa lèm bèm đó, là nỗi buồn đó ư?Gấu cũng đếch biết nữa! Gấu đứng ở nghĩa trang, ăn vận quần áo ngụy trang như là đang còn sống: quần áo rằn ri của lũ Ngụy… Nghĩa trang thì rẻ mạt: Họ đâu đòi hỏi chi nhiều Ngay mấy cái giỏ đựng rác cũng nhỏ xíu Thì chỉ đựng ba giấy gói bông, gói hoa, từ cửa tiệm. Nghĩa trang mới lịch sự và ngăn nắp làm sao "Ta sẽ không bao giờ quên mi đâu", Gấu Cái phán, và khắc lên tấm plaque bằng sành. Nhưng có đúng là mộ Gấu không đấy Hay là mộ một tên lính Ngụy vô danh nào đó?

31.12.2015. Trước giờ đóng cửa

tiệm, đón năm mới

PoemsPoem of Regret for an Old FriendBy Meghan O’RourkeWhat you did wasn’t so

bad. No, you’re right, it was

terrible. A dream is the only way

to breathe. When I think about this

life, Bài thơ ân hận về một người

bạn cũ

Điều bạn làm thì không quá

tệ Không, bạn nói đúng, quả là

khủng khiếp Một giấc mộng là cách độc nhất

để thở Note: Bài thơ mới nhất, trên

số báo mới nhất, đầu năm, 4 Tháng Giêng, của tờ The New Yorker.

Poems July 6, 2009 IssueA DreamBy Jorge Luis Borgeshttp://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2009/07/06/a-dream-3In a deserted place in Iran

there is a not very tall stone tower that has neither door

nor window. In the only room (with a dirt floor and shaped like

a circle) there is a wooden table and a bench. In that circular

cell, a man who looks like me is writing in letters I cannot understand

a long poem about a man who in another circular cell is writing a

poem about a man who in another circular cell . . . The process never

ends and no one will be able to read what the prisoners write. Tại 1 nơi hoang tàn ở Iran,

có 1 cái tháp không cao cho lắm, không cửa ra vào, không cửa

sổ. Ở căn phòng độc nhất (sàn tròn tròn, dơ dơ), có 1 cái

bàn gỗ, 1 cái băng ghế. Trong cái xà lim tròn tròn đó, một

người đàn ông trông giống Gấu, đang ngồi viết, bằng 1 thứ chữ Gấu

không đọc được, một bài thơ dài về 1 người đàn ông ở trong 1 xà lim

tròn tròn khác đang viết một bài thơ về một người đàn ông ở trong

1 xà lim tròn tròn khác… Cứ thế cứ thế chẳng bao giờ chấm dứt và chẳng

ai có thể đọc những tù nhân viết cái gì.

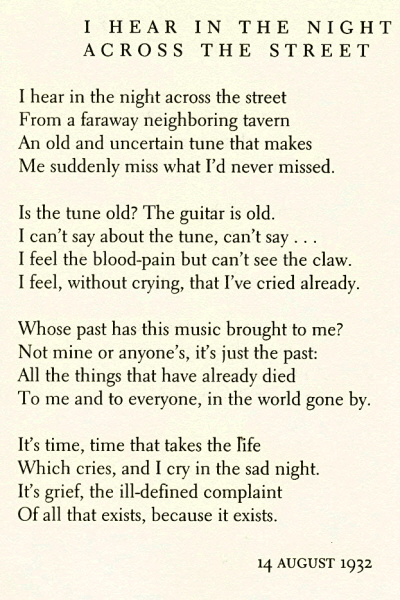

Tôi

nghe trong đêm, qua con phố, Điệu nhạc

xưa ư? Cây ghi ta cũ Quá

khứ nào, của ai, điệu nhạc mang về cho tôi? Đó

là thời gian, nó lấy đi cuộc đời Pessoa Dưới cầu Mirabeau, sông

Seine chảy Đêm tới, giờ đổ Tay trong tay mặt nhìn

mặt Đêm tới, giờ đổ Tình đi, như nước chảy Đêm tới giờ đổ Ngày đi, tháng đi Đêm tới, giờ đổ NQT dịch

Bên một dòng thơ

cổ xưa

sông khơi dòng trên tấm toan

thời xa

Huế, 11.2011 Tks. NQT Câu thơ đầu của

bạn làm Gấu nhớ đến Borges, và đoạn vừa đọc, trong Ngón

Thơ, This Craft of Verse, và cũng đã chôm 1 câu đưa lên Tin

Văn. Bữa nay, lạ làm sao đọc lại, thì nó lại bật ra dòng thơ của Apollinaire: Đêm

tới, giờ đổ, Cũng trong đoạn trên, trong

bài viết về "Ẩn dụ", Borges nhắc tới 1 cuốn tiểu thuyết, giản dị có cái tên,

Of Time and the River

[còn có 1 bài hát cùng tên, thật

tuyệt Gấu thật mê, khi mới lớn, Nat King Cole ca (1)

]. Nhưng đến đây, thì Borges đổi giọng: Ở đây, chúng ta có cái

khởi đầu của sự ghê rợn. Here we have the beginning of terror.

Hai dòng thơ của Apollinaire, ngược hẳn lại: Đêm

tới, giờ đổ Và rồi: L'amour s'en va comme cette

eau courante Tình bỏ đi như nước sông

chảy Về bài thơ của bạn, Gấu

mê mấy dòng cuối: tìm lại

người chuyện trò, cây già, quán cũ

cúi đầu dòng chữ hoen, trang sách ố có rủ nhau về, nhấp chén rượu bên bãi dâu, trong gió mùa vài lá thuyền gieo neo về một bến vắng chưa xa. Tuyệt. Nhất là

dòng cuối, "gieo neo về", "bến vắng chưa xa". NQT Note: Thay vì lời chúc đầu năm mới, tới tất cả bạn đọc TV, thì là những dòng thơ trên: Ôi, đời sao quá chậm, Mà hy vọng sao hung bạo đến như thế này! Note: Nhắc tới Nat King Cole, Bác Gúc [AP News] vừa loan tin, cô con gái của ông, Natalie Cole, 65 tuổi, mới mất.

LOS ANGELES (AP) — Singer

Natalie Cole, the daughter of jazz legend Nat “King” Cole who carried

on his musical legacy, has died.

Memory of France

Together with me recall: the sky of Paris,

that giant autumn crocus ... We went shopping for hearts at the flower girl's booth: they were blue and they opened up in the water. It began to rain in our room, and our neighbour came in, Monsieur Le Songe, a lean little man. We played cards, I lost the irises of my eyes; you lent me your hair, I lost it, he struck us down. He left by the door, the rain followed him out. We were dead and were able to breathe. Hồi ức Tây

Tôi và em cùng nhớ, bầu trời Paris, cái

màu vàng nghệ của Mùa Thu khổng lồ Đôi ta đi mua tâm hồn ở ki-ốt hoa của 1 cô gái Hoa thì xanh và chúng mở ra một vùng nước Trời bắt đầu mưa ở trong phòng của chúng ta Và người hàng xóm bước vô, Ông Mộng Mị, một người đàn ông nhỏ con, gầy ốm Chúng tôi chơi bài. Tôi thua cặp tròng đen; em cho tôi mượn mái tóc, tôi lại thua, anh ta vét chúng tôi đến cạn láng Anh ta đi ra cửa, cơn mưa theo anh ra ngoài Chúng tôi chết, và có thể thở. A LEAF, treeless

for Bertolt Brecht:

What times are these when a conversation is almost a crime because it includes so much made explicit? Một Cái Lá, không cây

Thời nào, những thời như thế nàygửi Bertolt Brecht Khi tán gẫu là một tội Bởi là vì nó bao gồm quá nhiều điều Nhờ tán gẫu mà trở thành dứt khoát? Homecoming

Snowfall, denser and denser, dove-coloured as yesterday, snowfall, as if even now you were sleeping. White, stacked into distance. Above it, endless, the sleigh track of the lost. Below, hidden, presses up what so hurts the eyes, hill upon hill, invisible. On each, fetched home into its (oday, an I slipped away into dumbness: wooden, a post. There: a feeling, blown across by the ice wind attaching its dove- its snow- coloured cloth as a flag. In Memoriam Paul Eluard

Lay those words into the dead man's grave which he spoke in order to live. Pillow his head amid them, let him feel the tongues of longing, the tongs. Lay that word on the dead man's eyelids which he refused to him who addressed him as thou, the word his leaping heart-blood passed by when a hand as bare as his own knotted him who addressed him as thou into the trees of the future. Lay this word on his eyelids: perhaps his eye, still blue, will assume a second, more alien blueness, and he who addressed him as thou will dream with him: We. Marina Tsvetayeva [Paul Celan trích dẫn làm tiêu đề cho 1 bài thơ của ông] Mọi thi sĩ là... Ngụy! Đúng ý Vương Đại Gia, Vương Trí Nhàn, "May mà có Ngụy"! |