|

|

|

Mark

Strand Tribute

Trước khi về

Lào ăn Tết Mít với lũ nhỏ, GCC đọc vội tờ NYRB, bài tưởng niệm nhà thơ

Mẽo mới

mất. Và có đi vài hàng về bài này.

Về lại Canada, nhân cái chân trái đang làm

eo, bèn nằm 1 chỗ, và lôi tờ báo ra đọc tiếp, thì phát giác ra 1 bài

thần sầu:

How Envy of

Jews Lay Behind It

“Why

the Germans? Why the Jews? Envy, Race Hatred, and the Prehistory of the

Holocaust”

The

historian George Mosse liked to tell a hypothetical story: if someone

had

predicted in 1900 that within fifty years the Jews of Europe would be

murdered,

one possible response would have been: “Well, I suppose that is

possible. Those

French or Russians are capable of anything.”

In Memory of

Joseph Brodsky

It could be

said, even here, that what remains of the self

Unwinds into

a vanishing light, and thins like dust, and heads

To a place

where knowing and nothing pass into each other, and

through;

That it

moves, unwinding still, beyond the vault of brightness ended,

And

continues to a place which may never be found, where the

unsayable,

Finally,

once more is uttered, but lightly, quickly, like random rain

That passes

in sleep, that one imagines passes in sleep.

What remains

of the self unwinds and unwinds, for none

Of the

boundaries holds-neither the shapeless one between us,

Nor the one

that falls between your body and your voice. Joseph,

Dear Joseph,

those sudden reminders of your having been-the

places

And times

whose greatest life was the one you gave them-now

appear

Like ghosts

in your wake. What remains of the self unwinds

Beyond us,

for whom time is only a measure of meanwhile

And the

future no more than et cetera et cetera ... but fast and

forever.

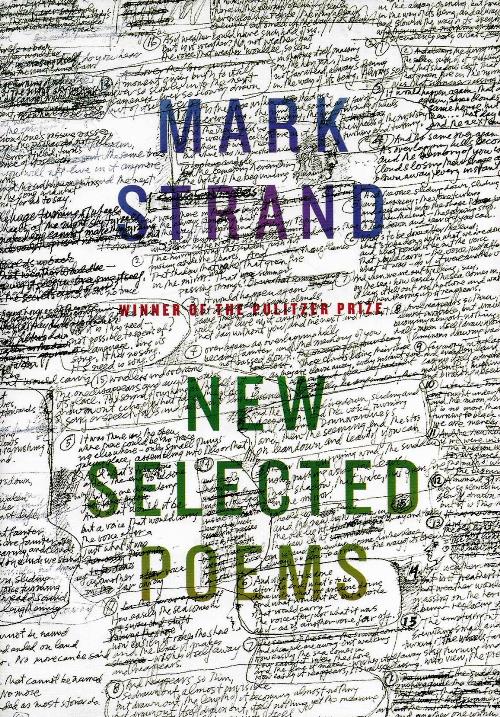

Mark Strand: New Selected Poems

Trong bài viết

của ông, về Mark Strand, được tờ NYRB cho đăng lại, cùng với bài của

Charles

Simic, như 1 tưởng niệm, Brodsky kể, lần đầu tiên ông đọc thơ Mark

Strand, khi

còn ở Liên Xô.

Bài cũng ngắn, Tin Văn scan và giới thiệu độc giả liền

sau đây,

cùng bài thơ của Mark Strand tưởng niệm Brodsky, và một… giai

thoại liên quan tới Brodsky, Mark Strand

và... nữ văn sĩ Thảo Trần, tức Gấu Cái!

Brodsky viết,

thơ của Mark Strand là thứ thơ mà thi sĩ không vặn tay độc giả đến trẹo

cả xương,

bắt phải đọc:

Technically speaking, Strand is a very

gentle poet: he never twists your arm, never forces you into a poem.

GCC đã sử dụng đòn này, để

nói về văn của Gấu Cái, nhân đọc bài viết của Thảo Trường, khi anh đọc

"Nơi

Dòng Sông Chảy Về Phía Nam" (1):

"Viết như không viết".

Tếu hơn nữa, là, 1 tay

blogger bèn chôm liền cụm từ này, để nói về 1 em

chân dài, trong 1 show trình diện trước công chúng Mít, ở trong nước:

Mặc như không mặc!

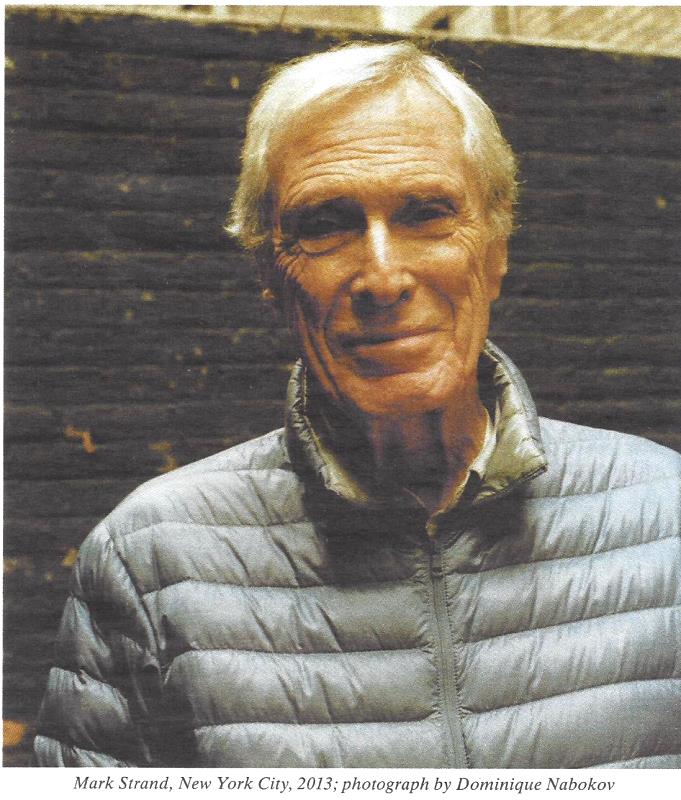

On Mark

Strand (1934-2014)

The poet

Mark Strand, a contributor to these pages, died on November 29.

JOSEPH

BRODSKY

The

following was given by Joseph Brodsky as an introduction to a reading

by Mark

Strand at the American Academy of Poets in New York City on November 4,

1986.

It's a tall

order to introduce Mark Strand because it requires estrangement from

what I

like very much, from something to which I owe many moments of almost

physical

happiness-or to its mental equivalent. I am talking about his poems-as

well as

about his prose, but poems first.

A man is,

after all, what he loves. But one always feels cornered when asked to

explain

why one loves this or that person, and what for. In order to ex-plain

it-which

inevitably amounts to explaining oneself-one has to try to love the

object of

one's attention a little bit less. I don't think I am capable of this

feat of

objectivity, nor am I willing even to try. In short, I feel biased

about Mark

Strand's poems, and judging by the way his work progresses, I expect to

stay

biased to the end of my days.

My romance

with Mr. Strand's poems dates back to the end of the Sixties, or to the

beginning of the Seventies, when an anthology of contemporary American

poetry-a

large paperback brick (edited by, I think, among others, Mark Strand)

landed

one day on my lap. That was in Russia. If my memory serves me right,

Strand's

entry in that anthology contained one of the best poems written in the

postwar

era, his "The Way It Is," with that terrific epigraph from Wallace

Stevens that I can't resist reproducing here:

The world is

ugly,

and the

people are sad.

What

impressed me there and then was a peculiar unassertiveness in depicting

fairly

dismal, in this poem's case, aspects of the human condition. I was also

impressed by the almost effortless pace and grace of the poem's

utterances. It

became apparent to me at once that I was dealing with a poet who

doesn't put

his strength on display-quite the contrary, who displays a sort of

flabby

muscle, who puts you at ease rather than imposes himself on the reader.

This

impression has stayed with me for some eighteen years, and even now I

don't see

that much reason for modifying it. Technically speaking, Strand is a

very

gentle poet: he never twists your arm, never forces you into a poem.

No, his

opening lines usually invite you in, with a genial, slightly elegiac

sweep of

intonation, and for a while you feel almost at home on the surface of

his

opaque, gray, swelling lines, until you realize-and not suddenly, with

a jolt,

but rather gradually and out of your own idle curiosity, the way one

some-

times looks out a skyscraper's window or overboard of a rowboat-how

many

fathoms are there underneath, how far you are from any shore. What's

more,

you'll find that depth, as well as that impossibility of return,

hypnotic.

But his

strategies aside, Mark Strand is essentially a poet of infinities, not

of affinities,

of things' cores and essences, not so much of their applications.

Nobody can

evoke absences, silences, emptinesses better than this poet, in whose

lines you

hear not regret but rather respect for those nonentities that surround

and

often engulf us. A usual Strand poem, to paraphrase Frost, starts in a

recognition yet builds up to a reverie-a reverie toward infinity

encountered in

a gray light of the sky, in the curve of a distant wave, in a case,

however, we

encounter the real thing: as real as it was in the case of Zbigniew

Herbert or

of Max Jacob, though I doubt very much that either was Strand's

inspiration.

For while those two Europeans were, very roughly putting it, carving

their remarkable

cameos of absurdity, Strand's prose poems-or rather, prose-looking

poems-unleash themselves with the maddening grandeur of purely lyrical

eloquence. These pieces are great, crackpot, unbridled orations,

monologues

whose chief driving force is pure linguistic energy, mulling over

clichés,

bureaucratese, psychobabble, literary passages, scientific lingo-you

name missed

chance, in a moment of hesitation. I often thought that should Robert

Musil

write verse, he'd sound like Mark Strand, except that when Mark Strand

writes

prose, he sounds not at all like Musil but rather like a cross between

Ovid and

Borges.

But before

we get to his prose, which I admire enormously and the reception of

which in

our papers I find nothing short of idiotic, I'd like to urge you to

listen to

Mark Strand very carefully, not because his poems are difficult, i.e.,

hermetic

or obscure-they are not- but because they evolve with the immanent

logic of a

dream, which calls for a somewhat heightened degree of attention. Very

often

his stanzas resemble a sort of slow-motion film shot in a dream that

selects

reality more for its open-endedness than for mechanical cohesion. Very

often

they give a feeling that the author managed to smuggle a camera into

his dream.

A reader more reckless than I would talk about Strand's surrealist

techniques;

I think about him as a realist, a detective, really, who follows

himself to the

source of his disquiet.

I also hope

that he is going to read tonight some of his prose, or some of his

prose poems.

One winces at this definition, and rightly so. In Strand's it-past

absurdity,

past common sense, on the way to the reader's joy.

Had that

writing been coming from the Continent, it would be all the rage on our

island.

As it is, it is coming from Salt Lake City, Utah, and while being

grateful to

the land of the Mormons for giving shelter to this writer, we should be

in all

honesty a bit ashamed for not being able to provide him with a place in

our

midst.

Joseph

Brodsky

A man is, after all, what he loves.

Brodsky

Nói cho cùng, một thằng đàn ông là "cái" [thay bằng "gái",

được không, nhỉ] hắn yêu.

"What", ở đây, nghĩa là gì?

Một loài chim biển, được chăng?

The world is ugly,

and the people are sad.

Đời thì xấu xí

Người thì buồn thế!

The Good

Life

You stand at

the window.

There is a

glass cloud in the shape of a heart.

The wind's

sighs are like caves in your speech.

You are the

ghost in the tree outside.

The street

is quiet.

The weather,

like tomorrow, like your life,

is partially

here, partially up in the air.

There is

nothing you can do.

The good

life gives no warning.

It weathers

the climates of despair

and appears,

on foot, unrecognized, offering nothing,

and you are

there.

Một đời OK

Mi đứng ở cửa

sổ

Mây thuỷ

tinh hình trái tim

Gió thở dài

sườn sượt, như hầm như hố, trong lèm bèm của mi

Mi là con ma

trong cây bên ngoài

Phố yên tĩnh

Thời tiết,

như ngày mai, như đời mi

Thì, một phần

ở đây, một phần ở mãi tít trên kia

Mi thì vô phương,

chẳng làm gì được với cái chuyện như thế đó

Một đời OK,

là một đời đếch đề ra, một cảnh báo cảnh biếc cái con mẹ gì cả.

Nó phì phào

cái khí hậu của sự chán chường

Và tỏ ra, trên

mặt đất, trong tiếng chân đi, không thể nhận ra, chẳng dâng hiến cái gì,

Và mi, có đó!

IN MEMORIAM

Give me six

lines written by the most honourable of men,

and I will

find a reason in them to hang him.

-Richelieu

We never

found the last lines he had written,

Or where he

was when they found him.

Of his

honor, people seem to know nothing.

And many

doubt that he ever lived.

It does not

matter. The fact that he died

Is reason

enough to believe there were reasons.

IN MEMORIAM

Cho ta sáu dòng

được viết bởi kẻ đáng kính trọng nhất trong những bực tu mi

Và ta sẽ tìm

ra một lý do trong đó để treo cổ hắn ta

-Richelieu

Chúng ta

không

kiếm ra những dòng cuối cùng hắn viết

Hay hắn ở đâu,

khi họ tìm thấy hắn

Về phẩm giá

của hắn, có vẻ như người ta chẳng biết gì

Và nhiều người

còn nghi ngờ, có thằng cha như thế ư

Nhưng cũng

chẳng sao, nói cho cùng

Sự kiện hắn

ngỏm là đủ lý do để mà tin rằng có những lý do.

Thơ

Mỗi Ngày

WINTER IN

NORTH LIBERTY

Snow falls,

filling

The moonlit

fields.

All night we

hear

The wind on

the drifts

And think of

escaping

This room,

this house,

The reaches

of ourselves

That winter

dulls.

Pale ferns

and flowers

Form on the

windows

Like grave

reminders

Of a summer

spent.

The walls

close in.

We lie apart

all night,

Thinking of

where we are.

We have no

place to go.

ELEVATOR

1.

The elevator

went to the base-

ment. The

doors opened.

A man

stepped in and asked if I

was going

up.

"I'm

going down," I said. "I won't

be going

up."

2.

The

elevator

went to the base-

ment. The

doors opened.

A man

stepped in and asked if

I was

going

up.

"I'm

going down," I said. "I won't

be going

up."

Mark Strand

poet

Mark Strand

(born 11 April 1934) is a Canadian-born American poet, essayist, and

translator. He was appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the

Library

of Congress in 1990. Since 2005–06, he has been a professor of English

and

Comparative Literature at Columbia University.

Strand was

born on Summerside, Prince Edward Island, Canada. His early years were

spent in

North America, while much of his teenage years were spent in South and

Central

America. In 1957, he earned his B.A. from Antioch College in Ohio.

Strand then

studied painting under Josef Albers at Yale University where he earned

a B.F.A

in 1959. On a Fulbright Scholarship, Strand studied nineteenth-century

Italian

poetry in Italy during 1960–1961. He attended the Iowa Writers'

Workshop at the

University of Iowa the following year and earned a Master of Arts in

1962. In

1965 he spent a year in Brazil as a Fulbright Lecturer.

Tell

yourself

as it gets cold and gray falls from the air

that you will go on

walking, hearing

the same tune no matter where

you find yourself—

inside the dome of dark

or under the cracking white

of the moon's gaze in a valley of snow.

Tonight as it gets cold

tell yourself

what you know which is nothing

but the tune your bones play

as you keep going. And you will be able

for once to lie down under the small fire

of winter stars.

And if it happens that you cannot

go on or turn back

and you find yourself

where you will be at the end,

tell yourself

in that final flowing of cold through your limbs

that you love what you are.

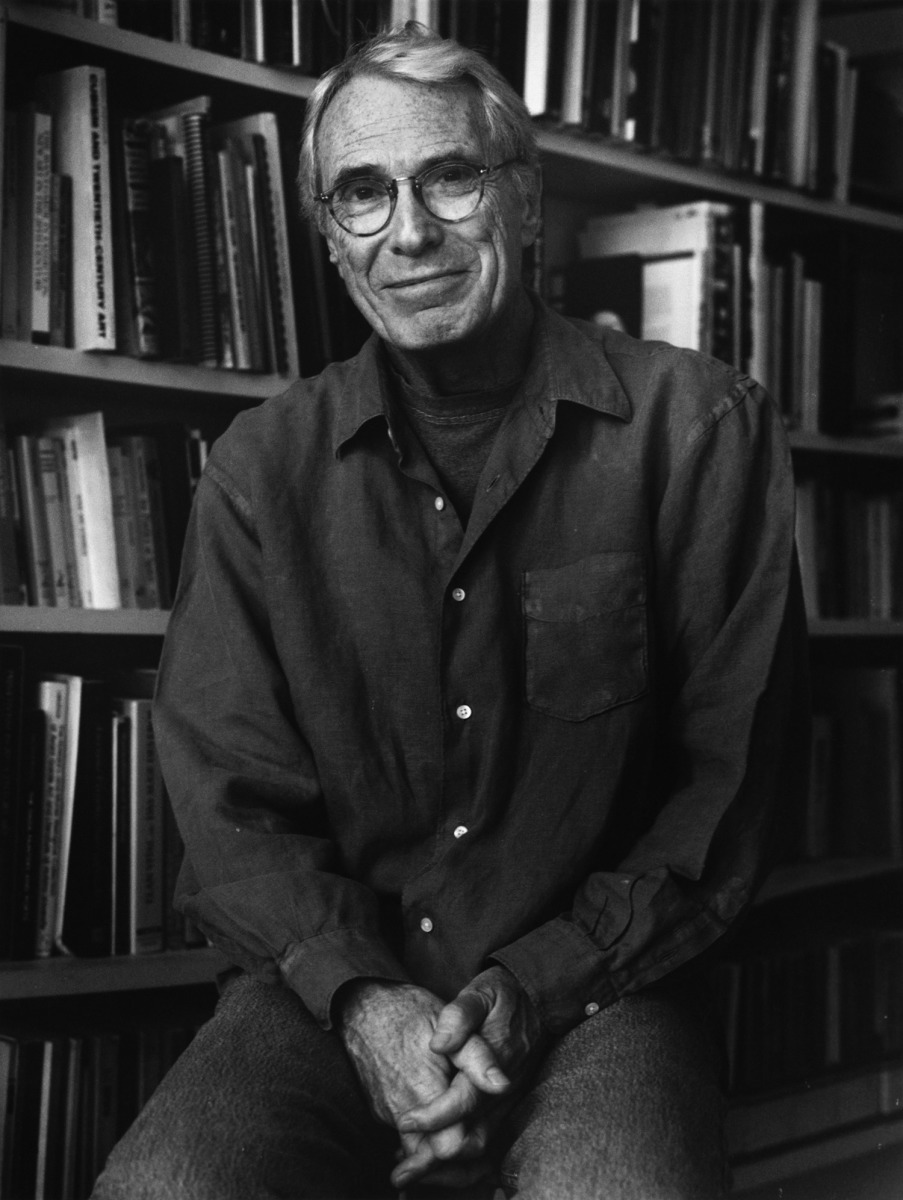

Mark

Strand,

1934 - 2014.

Mark

Strand,

1934 - 2014.

Credit PHOTOGRAPH BY

CHRIS FELVER / GETTY

Page-Turner

November 30, 2014

Mark Strand’s Last Waltz

By Dan Chiasson

The passing

of Mark Strand returns us to his poems and to his fine “Collected

Poems,”

published this year and long-listed for the National Book Award.

Strand’s poems

are often about the inner life’s methods of processing its social

manifestations. He wrote poetry in quiet and private; on trains, he

wrote

prose, because it was “less embarrassing,” as he told his friend

Wallace Shawn

in Strand’s Paris Review interview: “Who would understand a man of my

age

writing poems on a train, if they looked over my shoulder? I would be

perceived

as an overly emotional person.” Strand was an “overly emotional

person,” but

his courtesy warred with his intensity. How gallant to think of the

passenger

beside him, whose rights extend to not being seated next to a handsome

stranger

scribbling verses.

At least

since “Reasons For Moving” (1968), his second volume, Strand surveyed

his

outward circumstances—relative health and prosperity, growing fame, the

undeniable good fortune of being alive—from a peephole cut into the

exterior

wall of his solitude. The weirdness was all out there, where a suave

and

handsome man named Strand moved among other columns of flesh and bone;

in here,

alone with the moods, the mind, our memories of childhood and love, we

found

what Strand called, in his book-length poem of this name, “The

Continuous

Life.” It could be harrowing, but it was never proprietary: we all

shared the

same secret; Strand’s poems of the inner life were sometimes like

expressions

of our own: “some shy event, some secret of the light that falls upon

the

deep/Some source of sorrow that does not wish to be discovered yet.”

(“Our

Masterpiece Is the Private Life.”)

“The

Continuous Life” continues after death, whose abrupt appearance,

breaking up

the party, Strand often described. Life is a waltz, a “Delirium Waltz,”

as he

called it in his greatest poem—collected in his best book, one of the

finest of

the past fifty years, “Blizzard of One”—which ends when the music ends.

It is

in the nature of waltzes that we cannot foretell their duration ahead

of time.

Waltzing to delirium, we might think that they never end. And then the

music

stops. It happened on Saturday for Strand, a great poet and a kind man.

Here is

“2002,” one of the bleakly comic poems he wrote in anticipation of that

moment:

I am not

thinking of Death, but Death is thinking of me.

He leans

back in his chair, rubs his hands, strokes

His beard

and says, “I’m thinking of Strand, I’m thinking

That one of

these days I’ll be out back, swinging my scythe

Or holding

my hourglass up to the moon, and Strand will appear

In a jacket

and tie, and together under the boulevards’

Leafless

trees we’ll stroll into the city of souls. And when

We get to

the Great Piazza with its marble mansions, the crowd

That had

been waiting there will welcome us with delirious cries,

And their

tears, turned hard and cold as glass from having been

Held back so

long, will fall, and clatter on the stones below.

O let it be

soon. Let it be soon.”

On Mark

Strand (1934–2014)

Joseph

Brodsky and Charles Simic

January 8,

2015 Issue

The poet

Mark Strand, a contributor to these pages, died on November 29.

Note: Tin Văn sẽ

đi bài này, từ báo giấy, tất nhiên!

JOSEPH

BRODSKY

The

following was given by Joseph Brodsky as an introduction to a reading

by Mark

Strand at the American Academy of Poets in New York City on November 4,

1986.

It’s a tall

order to introduce Mark Strand because it requires estrangement from

what I

like very much, from something to which I owe many moments of almost

physical

happiness—or to its mental equivalent. I am talking about his poems—as

well as

about his prose, but poems first.

A man is,

after all, what he loves. But one always feels cornered when asked to

explain

why one loves this or that person, and what for. In order to explain

it—which

inevitably amounts to explaining oneself—one has to try to love the

object of

one’s attention a little bit less. I don’t think I am capable of this

feat of

objectivity, nor am I willing even to try. In short, I feel biased

about Mark

Strand’s poems, and judging by the way his work progresses, I expect to

stay

biased to the end of my days.

My romance

with Mr. Strand’s poems dates back to the end of the Sixties, or to the

beginning of the Seventies, when an anthology of contemporary American

poetry—a

large paperback brick (edited by, I think, among others, Mark Strand)

landed

one day on my lap. That was in Russia. If my memory serves me right,

Strand’s

entry in that anthology contained one of the best poems written in the

postwar

era, his “The Way It Is,” with that terrific epigraph from Wallace

Stevens that

I can’t resist reproducing here:

The world is ugly,

and the people

are sad.

What

impressed me there and then was a peculiar unassertiveness in depicting

fairly

dismal, in this poem’s case, aspects of the human condition. I was also

impressed by the almost effortless pace and grace of the poem’s

utterances. It

became apparent to me at once that I was dealing with a poet who

doesn’t put

his strength on display—quite the contrary, who displays a sort of

flabby

muscle, who puts you at ease rather than imposes himself on the reader.

This

impression has stayed with me for some eighteen years, and even now I

don’t see

that much reason for modifying it. Technically speaking, Strand is a

very

gentle poet: he never twists your arm, never forces you into a poem.

No, his

opening lines usually invite you in, with a genial, slightly elegiac

sweep of

intonation, and for a while you feel almost at home on the surface of

his

opaque, gray, swelling lines, until you realize—and not suddenly, with

a jolt,

but rather gradually and out of your own idle curiosity, the way one

sometimes

looks out a skyscraper’s window or overboard of …

*

A man is,

after all, what he loves.

Nói cho

cùng, một thằng đàn ông là "cái" [thay bằng "gái", được

không, nhỉ] hắn yêu.

"What",

ở đây, nghĩa là gì?

Một loài

chim biển, được chăng?

The world is

ugly,

and the

people are sad.

Đời thì xấu xí

Người thì buồn thế!

ELEVATOR

1.

The elevator

went to the base-

ment. The

doors opened.

A man

stepped in and asked if I

was going

up.

"I'm

going down," I said. "I won't

be going

up."

2.

The

elevator

went to the base-

ment. The

doors opened.

A man

stepped in and asked if

I was going

up.

"I'm

going down," I said. "I won't

be going

up."

|

|