I Why The Classics

Bei Dao Zbigniew Herbert Zagajewski R. Carver Milosz Bolano Poems Charles Simic Brodsky Borges Cavafy_Ithaca Octavio Paz Thu 2013 NXH's Poems of the Night Lửa & Khoa Hữu & Celan TNH Poems Haiku_Buson Xmas 26 Dec 1999 Mark Strand Mahmoud Darwish W.S. Merwin TTT_9_Years Trang thơ Dã Viên The Lunatic by Simic Map by Szymborska Serbian Poetry ed by Simic Baczinski by AZ A Defense of Ardor by AZ |

Album | Thơ | Tưởng Niệm | Nội cỏ

của

thiên đường | Passage Eden | Sáng

tác | Sách mới xuất bản | Chuyện văn

Dịch thuật | Dịch ngắn | Đọc sách | Độc giả sáng tác | Giới thiệu | Góc Sài gòn | Góc Hà nội | Góc Thảo Trường Lý thuyết phê bình | Tác giả Việt | Tác giả ngoại | Tác giả & Tác phẩm | Text Scan | Tin văn vắn | Thời sự | Thư tín | Phỏng vấn | Phỏng vấn dởm | Phỏng vấn ngắn Giai thoại | Potin | Linh tinh | Thống kê | Viết ngắn | Tiểu thuyết | Lướt Tin Văn Cũ | Kỷ niệm | Thời Sự Hình | Gọi Người Đã Chết Ghi chú trong ngày | Thơ Mỗi Ngày | Chân Dung | Jennifer Video Nhật Ký Tin Văn/ Viết Thơ Mỗi Ngày  Gió

Hà Nội trong hồn người xa xứ Note: LMH có thể nói, là do

GCC khám phá ra, trong khi chính những kẻ ra đi từ Miền Bắc, thì lại dè

bỉu, “cái

Hà mà viết cái gì”, như 1 tay viết mail riêng cho GCC nhận xét, hay như

em Y Bọt

gì đó, 1 nhà văn trong nước được dịp ra hải ngoại, “viết thua cả học

trò của

tui”, hình như bà này đã từng phát biểu. Tuy nhiên, khi GCC nhận xét

LMH, hồi mới đọc bà, là từ 1 viễn ảnh của tương lai, của 1 miền đất,

cùng với nó

là thứ văn chương, như con phượng hoàng tái sinh từ tro than, như của

lũ Ngụy,

sau 1975, không phải thứ văn chương hoài niệm - như cách đọc LMH ở đây

- cũng

như cách mà đám VC đọc văn chương trước 1975 của Miền Nam, khi cho in

lại một số

tác phẩm của họ, bằng cách cắt xén, sao cho vừa cái nhìn kiểm duyệt của

chúng. NQT Khi đọc cái

tít, Phố Vẫn Gió, Gấu nghĩ, liệu nó trong dòng “Gió từ thời khuất mặt?” The

human face disappeared and also its divine image. In the classical

world a slave was called aprosopos, 'faceless'; litteraly, one who

cannot to be seen. The Bolsheviks gloried in facelessness. As

though, in night's terrible mirror **** .... All writing

is a species of remembering. If there is anything triumphalist about Another

Beauty it is that the acts of remembering the book contains

seem so

frictionless. Imagining-that is, bringing the past to mental life-is

there as

needed; it never falters; it is by definition a success. The recovery

of

memory, of course, is an ethical obligation: the obligation to persist

in the

effort to apprehend the truth. This seems less apparent in America,

where the

work of memory has been exuberantly identified with the creation of

useful or

therapeutic fictions, than in Zagajewski's lacerated corner of the

world. To

recover a memory-to secure a truth-is a supreme touch-stone of value in

Another

Beauty. "I didn't witness the extermination

of the Jews," he writes: That every

generation fears, misunderstands, and condescends to its

successor-this, too,

is a function of the equivalence of history and memory (history being

what it

is agreed on, collectively, to remember). Each generation has its

distinctive

memories, and the elapsing of time, which brings with it a steady

accumulation

of loss, confers on those memories a normativeness which cannot

possibly be

honored by the young, who are busy compiling their memories, their

benchmarks.

One of Zagajewski's most moving portraits of elders is of Stefan

Szuman, an

illustrious member of the interwar Polish intelligentsia (he had known

Stanislaw Witkiewicz and Bruno Schulz) and now a retired professor at

the

university living in isolation and penury. Its point is Zagajewski's

realization, thinking back, that he and his literary friends could only

have

seemed like fools and savages, "shaped by a postwar education, by new

schools, new papers, new radio, new TV;" to the defeated, homely,

embittered Szuman and his wife. The rule seems to be: each generation

looks

upon its successor generation as barbarians. Zagajewski, himself no

longer

young and now a teacher of American students, is committed to not

eplicating,

in his turn, that kind of despair and incomprehension. Nor is he

content to

write off an entire older Polish generation of intellectuals and

artists, his

generation's "enemy"-the true believers and those who just sold out-for

turpitude and cowardice: they weren't simply devils, any more than he

and his

friends were angels. As for those "who began by serving Stalin's

civilization" but then changed, Zagajewski writes: "I don't condemn

them for their early, youthful intoxication. I'm more inclined to

marvel at the

generosity of human nature, which offers gifted young people a second

chance,

the opportunity for a moral comeback." At the heart of this assessment

is

the wisdom of the novelist, a professional of empathy, rather than that

of a

lyric poet. (Zagajewski has written four novels, none as yet translated

into

English.) The dramatic monologue "Betrayal" in Two Cities begins: Why

did I do that? Why did I do what? Why was I who I was? And who was I? I am already beginning to regret that I agreed to grant you this interview. For years I refused; you must have asked me at a weak moment or in a moment of anxiety .... What did that world look like? The one you were too late to get to know. The same as this one. Completely different. That everything is always different ... and the same: a poet's wisdom. Actually, wisdom tout court. Of course, history should never be thought of with a capital H. The governing sense of Zagajewski's memory-work is his aware- ness of having lived through several historical periods, in the course of which things eventually got better. Modestly, imperfectly-not utopianly-better. The young Zagajewski and his comrades in dissidence had assumed that communism would last another hundred, two hundred years, when, in fact, it had less than two decades to go. Lesson: evil is not immutable. The reality is, everyone outlives an old self, often more than one, in the course of a reasonably long life. Susan Sontag: The Wisdom Project Tớ đếch chứng

kiến Lò Thiêu, làm cỏ Do Thái. Tớ sinh trễ quá. Tớ sinh ra và chứng

kiến tiến

trình qua đó Âu Châu tìm đường nhớ chính nó. Hồi nhớ Bắc

Kít, ngay từ bây giờ, đã vờ mấy cú: Quên mẹ cái “ơn trời biển” của

Thiên Triều Trong "Trò

Chuyện với Brodsky", của Volkov, chương chót, "St. Petersburg: Memories

of the

Future", Hồi Nhớ Tương Lai, đọc thú lắm, và áp dụng vô Hà Nội thật là

tuyệt. GCC đọc LMH,

để kiếm cái ấn bản của riêng Gấu, về nó.  Người đàn ông làm tôi nhớ tới người Tầu già bán lạc rang ở bờ hồ Hà Nội. Tôi có nhiều kỷ niệm về thành phố nhỏ bé và cũ kỹ đó. Nhà tôi ở Bạch Mai, gần ngay bên đường xe điện. Tôi thường tinh nghịch để những viên sỏi nhỏ lên trên đường sắt, rồi hồi hộp chờ chuyến xe chạy qua. Suốt thời thơ ấu, tôi bị chiếc xe điện mê hoặc. Một lần trốn vé xe, tôi cùng một thằng bé đánh giầy ngồi ở cuối tầu, nơi dùng để nối hai toa xe lại với nhau. Thằng bé đánh giầy nói, nó thường ngồi như vậy, ngay cả khi có tiền mua vé. Hôm đó trời lạnh, tôi đội một chiếc béret dạ đen, một tay nắm vào thanh sắt, một tay cầm cặp sách vở. Thằng bé đánh giầy đầu tóc bù xù, tay cầm hộp đồ nghề, tay cầm khúc bánh mì nhai ngồm ngoàm. Những người đi đường nhìn chúng tôi với vẻ buồn cười, ngạc nhiên. Lúc đầu tôi rất sợ, nhưng dần dần cảm thấy thích thú. Bỗng nhiên, không hiểu sao, tôi nhớ lại được một đoạn nhạc tôi đã quên từ lâu, và tôi hát nho nhỏ, đầu lắc lư theo điệu nhạc. Thằng bé đánh giầy nhìn tôi cười ngặt nghẽo. Tôi tức giận, hát thật lớn, vừa hát vừa đập vào thành xe ầm ầm. Bỗng tôi cảm thấy đầu lành lạnh. Tôi ngửng lên, và thấy người soát vé đang giận dữ nhìn tôi, tay cầm chiếc mũ dạ. Thằng bé đánh giầy vẫn tiếp tục cười, tôi ngưng hát, và ngưng đập vào thành xe. Cuối cùng không biết nghĩ sao, người soát vé vứt chiếc dạ xuống đường. Xe lúc đó đang chạy nhanh. Tôi cúi nhìn xuống con đường nhựa chạy vùn vụt, tôi sợ hãi không dám nhảy xuống. Tôi chợt nghĩ tới đến cha tôi. Tôi nhìn thằng bé đánh giầy ra vẻ cầu cứu. Nó nhẩy xuống, nhặt chiếc mũ dạ, đội lên đầu, rồi nhìn tôi nhe răng cười, tỏ vẻ chế nhạo. Sau đó, tôi thỉnh thoảng gặp thằng bé đánh giầy quanh quẩn tại khu tôi ở, đầu đội chiếc mũ dạ của tôi. Mỗi lần thoáng thấy nó, là tôi vội vã lẩn tránh, chỉ sợ nó nhận ra tôi. Note: Hình dưới đây, "cũng" Phố Cổ Hà Nội!

Gió

Hà Nội trong hồn người xa xứ Note: LMH có thể nói, là do

GCC khám phá ra, trong khi chính những kẻ ra đi từ Miền Bắc, thì lại dè

bỉu, “cái

Hà mà viết cái gì”, như 1 tay viết mail riêng cho GCC nhận xét, hay như

em Y Bọt

gì đó, 1 nhà văn trong nước được dịp ra hải ngoại, “viết thua cả học

trò của

tui”, hình như bà này đã từng phát biểu. Tuy nhiên, khi GCC nhận xét

LMH, hồi mới đọc bà, là từ 1 viễn ảnh của tương lai, của 1 miền đất,

cùng với nó

là thứ văn chương, như con phượng hoàng tái sinh từ tro than, như của

lũ Ngụy,

sau 1975, không phải thứ văn chương hoài niệm - như cách đọc LMH ở đây

- cũng

như cách mà đám VC đọc văn chương trước 1975 của Miền Nam, khi cho in

lại một số

tác phẩm của họ, bằng cách cắt xén, sao cho vừa cái nhìn kiểm duyệt của

chúng. NQT Khi đọc cái

tít, Phố Vẫn Gió, Gấu nghĩ, liệu nó trong dòng “Gió từ thời khuất mặt?” The

human face disappeared and also its divine image. In the classical

world a slave was called aprosopos, 'faceless'; litteraly, one who

cannot to be seen. The Bolsheviks gloried in facelessness. **** .... All writing

is a species of remembering. If there is anything triumphalist about Another

Beauty it is that the acts of remembering the book contains

seem so

frictionless. Imagining-that is, bringing the past to mental life-is

there as

needed; it never falters; it is by definition a success. The recovery

of

memory, of course, is an ethical obligation: the obligation to persist

in the

effort to apprehend the truth. This seems less apparent in America,

where the

work of memory has been exuberantly identified with the creation of

useful or

therapeutic fictions, than in Zagajewski's lacerated corner of the

world. To

recover a memory-to secure a truth-is a supreme touch-stone of value in

Another

Beauty. "I didn't witness the extermination

of the Jews," he writes: That every

generation fears, misunderstands, and condescends to its

successor-this, too,

is a function of the equivalence of history and memory (history being

what it

is agreed on, collectively, to remember). Each generation has its

distinctive

memories, and the elapsing of time, which brings with it a steady

accumulation

of loss, confers on those memories a normativeness which cannot

possibly be

honored by the young, who are busy compiling their memories, their

benchmarks.

One of Zagajewski's most moving portraits of elders is of Stefan

Szuman, an

illustrious member of the interwar Polish intelligentsia (he had known

Stanislaw Witkiewicz and Bruno Schulz) and now a retired professor at

the

university living in isolation and penury. Its point is Zagajewski's

realization, thinking back, that he and his literary friends could only

have

seemed like fools and savages, "shaped by a postwar education, by new

schools, new papers, new radio, new TV;" to the defeated, homely,

embittered Szuman and his wife. The rule seems to be: each generation

looks

upon its successor generation as barbarians. Zagajewski, himself no

longer

young and now a teacher of American students, is committed to not

eplicating,

in his turn, that kind of despair and incomprehension. Nor is he

content to

write off an entire older Polish generation of intellectuals and

artists, his

generation's "enemy"-the true believers and those who just sold out-for

turpitude and cowardice: they weren't simply devils, any more than he

and his

friends were angels. As for those "who began by serving Stalin's

civilization" but then changed, Zagajewski writes: "I don't condemn

them for their early, youthful intoxication. I'm more inclined to

marvel at the

generosity of human nature, which offers gifted young people a second

chance,

the opportunity for a moral comeback." At the heart of this assessment

is

the wisdom of the novelist, a professional of empathy, rather than that

of a

lyric poet. (Zagajewski has written four novels, none as yet translated

into

English.) The dramatic monologue "Betrayal" in Two Cities begins: Why

did I do that? Why did I do what? Why was I who I was? And who was I? I am already beginning to regret that I agreed to grant you this interview. For years I refused; you must have asked me at a weak moment or in a moment of anxiety .... What did that world look like? The one you were too late to get to know. The same as this one. Completely different. That everything is always different ... and the same: a poet's wisdom. Actually, wisdom tout court. Of course, history should never be thought of with a capital H. The governing sense of Zagajewski's memory-work is his aware- ness of having lived through several historical periods, in the course of which things eventually got better. Modestly, imperfectly-not utopianly-better. The young Zagajewski and his comrades in dissidence had assumed that communism would last another hundred, two hundred years, when, in fact, it had less than two decades to go. Lesson: evil is not immutable. The reality is, everyone outlives an old self, often more than one, in the course of a reasonably long life. Susan Sontag: The Wisdom Project Tớ đếch chứng

kiến Lò Thiêu, làm cỏ Do Thái. Tớ sinh trễ quá. Tớ sinh ra và chứng

kiến tiến

trình qua đó Âu Châu tìm đường nhớ chính nó. Hồi nhớ Bắc

Kít, ngay từ bây giờ, đã vờ mấy cú: Quên mẹ cái “ơn trời biển” của

Thiên Triều SONG ABOUT

SONGS It will burn

you at the start, And a heart

full of spite Others will

reap. I only sow.

1916 Akhmatova Writing when I mount

a chair in the

table's wilderness for a little

while longer FURNISHED ROOM In this room

there are three suitcases when I open

the door one picture

on the wall I never saw

Vesuvius the other

picture out of the

shadow on the table

a knife a napkin following a

golden light the leaves

breathe in the light an untrue

world flaking

wallpaper In my room Zbigniew

Herbert: The Collected Poems

1956-1998 NINA

ZIVANCEVC Zivancevic was born in Belgrade. She is a literary critic, journalist, and translator as well as a poet. She lived for several years in New York, where she wrote in English, and now resides in Paris. New Rivers Press published a book of her poems, More or Less Urgent, in 1980. The poems in this anthology come from her books The Spirit of Renaissance (1989) and At the End of the Century (2006). Ode to Western Wind

O, great

great Western wind, Charles

Simic: The Horse Has Six Legs, an

anthology of Serbian Poetry.

The one they

roll out in a wheelchair While

pigeons take turns landing Charles

Simic LRB [London

Review of Books] May 9 2013 Trong thời gian ngọt

ngào của riêng nó Cái lá còn lại,

lâu lâu khẽ run 1 phát Thằng chả ngồi

xe lăn Khi bồ câu xếp

hàng

ON THE

BROOKLYN BRIDGE Perhaps

you're one of the many dots at sunset The one,

whose family doesn't want to hear from, And what

about the one I'm always hoping to run into? Trên cầu Brooklyn

Bridge Có lẽ em là

một cái chấm nhỏ trong rất nhiều chấm chấm vào lúc mặt trời lặn Hay là một cái

chấm mà gia đình không thèm muốn nghe nói tới Tuy nhiên chán làm sao anh không làm sao nhớ ra nổi khuôn mặt em Ở tiệm cà phê Starbucks buổi sáng bữa đó Em có thể là một trong vài người lần lữa, Hay cái người mà đã biến mất từ MCNK [một chủ nhật khác] không hề có? Cái người mà anh lần cuối nhìn lại Như nhìn lại Xề Gòn Đã mất? Neither the

intimacy of your look, your brow fair as

[Robert Fitzgerald] J.L. Borges: Selected Poems

1923-1967 Đường vào tình

yêu Không phải mùi cơ thể của em, tuy vưỡn bí hiểm, vưỡn dành riêng cho anh, và vưỡn muôn đời trẻ thơ Không phải điều đến với anh, từ em, bằng lời, hay bằng im lặng Sẽ cực kỳ bí ẩn, như một món quà Khi nhìn thấy em ngủ, Cuộn tròn, thánh thiện, như thiên thần, như thánh nữ trong tay anh Thánh nữ, again, như lời kinh, bằng cái quyền uy thấm nhập của giấc ngủ lặng lẽ, long lanh, như một điều “gọi là” hạnh phúc, được tìm thấy lại, từ hồi nhớ Em sẽ cho anh bến bờ đó của đời em, mà em, chính em, không sở hữu. Nhập vào im lặng Anh sẽ nhận ra bãi biển tối hậu của sự hiện hữu là em Và sẽ nhìn thấy em lần đầu, có lẽ, Như Ông Giời phải, bắt buộc phải, chiêm ngưỡng em, như thế - Giả tưởng của Thời Gian bị hủy diệt Vô tư thoát ra khỏi tình yêu Thoát ra khỏi anh. Poem in the

Manner of William Wordsworth By David

Lehman I ran with

the wind like a boy And thus was

born my theory of joy If such a

thought were vain, Not even—my

sister, my life—not in body

bruised but with dignity high, Bài thơ ăn theo William Wordsworth Tôi chạy cùng

với gió như một đứa bé Và như thế bèn

sinh ra lý thuyết của tôi về vui Giả như một

tư tưởng như thế chỉ là vô ích, nhảm nhí đối với tôi Ngay cả - chị

tôi, đời tôi - Trong cái thân

xác bầm tím nhưng với phẩm giá cao

Charity The

off-white hairpiece on the hedge The snowman

prisoner down the road His head

fell off last night and we Lòng từ thiện Mớ tóc giả màu

ngà ở bờ rào Người tù tuyết

nhân ở cuối đường Cái đầu rớt

ra tối hôm qua ALISTAIR

ELLIOT TLS June 5 2015 Anticipation

of Love Neither the

intimacy of your look, your brow fair as a feast day,

-R.F.  Extrait J'ai appris à parler dans

une région brouillée Gấu học nói trong 1 vùng

lù tà mù Hà, hà!

You are my silent

brethren, In old letters I find

traces of your writing, Your addresses and phone

numbers pitch camp I was in Paris yesterday,

I saw hundreds of tourists, You'd think it would be

easy, living. You are my masters, Adam Zagajewski: Mysticism for Beginners Đồng bào

Các bạn là đồng bào im lặng của tớ Trong những lá thư cũ tớ kiếm

thấy những nét chữ của các bạn, Địa chỉ và số phôn của các bạn

thì cắm trại Bữa hôm qua, tớ ở Paris, và tớ thấy hàng trăm

du khách, mệt mỏi, rét run. Các bạn nghĩ, sống thì cũng dễ dàng thôi Những người chết Đừng quên tớ.  Canvas I stood in

silence before a dark picture, I stood in

silence before the dark canvas, of moments

of helplessness striking

what it loves, Canvas Tôi đứng im

lặng trước bức hình tối thui Tôi đứng in

lặng trước tấm vải bố tối thui Tới những

khoảnh khắc vô vọng Thoi, cái yêu For Czeslaw

Milosz How

unattainable life is, it only reveals Adam

Zagajewski: Canvas Trái Làm sao mà

tó được cuộc đời THE GREAT

POET HAS GONE Of course

nothing changes When the

great poet has gone,

Nhà thơ lớn

đã ra đi Lẽ dĩ nhiên

chẳng có gì thay đổi Khi nhà thơ

lớn ra đi Tới trưa, vẫn

thứ tiếng ồn đó nổi lên, Khi chúng ta

bỏ đi, một chuyến đi dài Le poète

intraitable Il ne peut

toutefois adhérer au marxisme: la lecture de Simone Weil (qu'il traduit

en

polonais) a joué à cet égard un rôle capital dans son évolution

intellectuelle.

Elle aura été la première à dévoiler la contradiction dans les termes

que

représente le « matérialisme dialectique ». Pour une pensée

intégralement

matérialiste (comme celle d'Engels), l'histoire est le produit de

forces

entièrement étrangères à l'individu, et l'avènement de la société

communiste, une

conséquence logique de l'histoire; la liberté n'y a aucune place. En y

introduisant la « dialectique ", Marx réaffirme que l'action des

individus

est malgré tout nécessaire pour qu'advienne la société idéale: mais

cette

notion amène avec elle l'idéalisme hégélien et contredit à elle seule

le

matélialisme. C'est cette contradiction qui va conduire les sociétés «

socialistes" à tenir l'individu pour quantité négligeable tout en

exigeant

de lui qu'il adhère au sens supposé inéluctable de l'histoire. Mais la

philosophie de Simone Weil apporte plus encore à Milosz que cette

critique:

elle lui livre les clés d'une anthropologie chrétienne qui, prolongeant

Pascal,

décrit l'homme comme écartelé entre la « pesanteur" et la « grâce ". Nhà thơ

không làm sao “xử lý” được. Tuy nhiên,

ông không thể vô Mác Xít: Việc ông đọc Simone Weil [mà ông dịch qua

tiếng Ba

Lan] đã đóng 1 vai trò chủ yếu trong sự tiến hóa trí thức của ông. Bà

là người

đầu tiên vén màn cho thấy sự mâu thuẫn trong những thuật ngữ mà chủ

nghĩa duy vật

biện chứng đề ra. Ðối với một tư tưởng toàn-duy vật [như của Engels],

lịch sử

là sản phẩm của những sức mạnh hoàn toàn xa lạ với 1 cá nhân con người,

và cùng

với sự lên ngôi của xã hội Cộng Sản, một hậu quả hữu lý của lịch sử; tự

do chẳng

hề có chỗ ở trong đó. Khi đưa ra cái từ “biện chứng”, Marx tái khẳng

định hành

động của những cá nhân dù bất cứ thế nào thì đều cần thiết để đi đến xã

hội lý

tưởng: nhưng quan niệm này kéo theo cùng với nó, chủ nghĩa lý tưởng của

Hegel,

và chỉ nội nó đã chửi bố chủ nghĩa duy vật. Chính mâu thuẫn này dẫn tới

sự kiện,

những xã hội “xã hội chủ nghĩa” coi cá nhân như là thành phần chẳng

đáng kể, bọt

bèo của lịch sử, [như thực tế cho thấy], trong khi đòi hỏi ở cá nhân,

phải tất

yếu bọt bèo như thế. Nhưng triết học của Simone Weil đem đến cho Milosz

quá cả

nền phê bình đó: Bà đem đến cho ông những chiếc chìa khoá của một nhân

bản học

Ky Tô, mà, kéo dài Pascal, diễn tả con người như bị chia xé giữa “trọng

lực” và

“ân sủng”. Chúng ta phải

coi cái đẹp như là trung gian giữa cái cần và cái tốt (mediation

between

necessity and the good), giữa trầm trọng và ân sủng (gravity and

grace). Milosz

cố triển khai tư tưởng này [của Weil], trong

tác phẩm “Sự Nắm Bắt Quyền Lực”, tiếp theo

“Cầm Tưởng”. Đây là một

cuốn tiểu thuyết viết hối hả, với ý định cho tham dự một cuộc thi văn

chương,

nghĩa là vì tiền, và cuối cùng đã đoạt giải! Viết hối hả, vậy mà chiếm

giải,

nhưng thật khó mà coi đây là một tuyệt phẩm. Ngay chính tác giả cũng vờ

nó đi,

khi viết Lịch Sử Văn Học Ba Lan. Tuy nhiên, đây là câu chuyện của thế

kỷ. Nhân

vật chính của cuốn tiểu thuyết tìm cách vượt biên giới Nga, để sống

dưới chế độ

Nazi, như Milosz đã từng làm như vậy. THE

IMPORTANCE OF SIMONE WElL FRANCE

offered a rare gift to the contemporary world in the person of Simone

Weil. The

appearance of such a writer in the twentieth century was against all

the rules of

probability, yet improbable things do happen. The life of

Simone Weil was short. Born in 1909 in Paris, she died in England in

1943 at

the age of thirty-four. None of her books appeared during her own

lifetime.

Since the end of the war her scattered articles and her

manuscripts-diaries,

essays-have been published and translated into many languages. Her work

has

found admirers all over the world, yet because of its austerity it

attracts

only a limited number of readers in every country. I hope my

presentation will

be useful to those who have never heard of her. [suite] Czeslaw

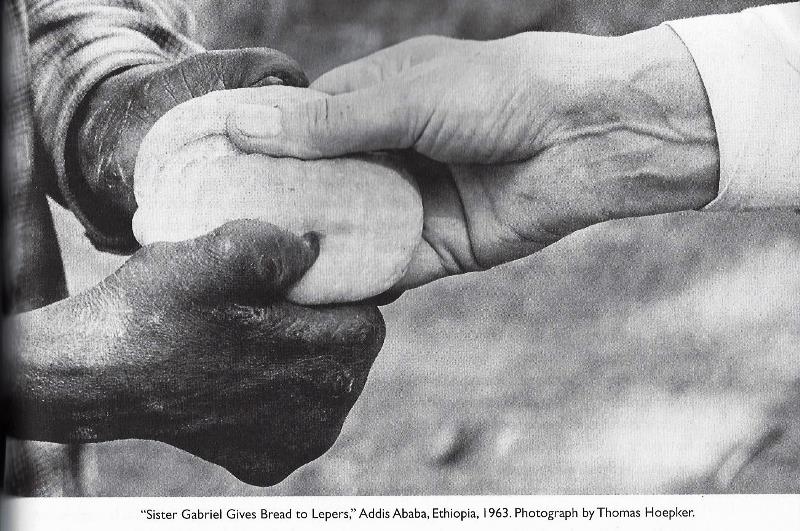

Milosz  Trong số báo

về Lòng Từ Thiện, có bài của Simone Weil, trích từ The Need for Roots. Trong tiểu

sử của bà, có trích dẫn một câu, của Susan Sontag, viết về Weil: [From The

Need for Roots]. Born in Paris in 1909, Weil dedicated her lift to

advocating

for the poor and disenfranchised. She worked as a teacher, trained with

an

anarchist unit during the Spanish Civil War, and once debated Leon

Trotsky in

her parents' apartment after arranging for him to hold a clandestine

meeting

there. Weil's uncompromising asceticism led Susan Sontag to declare,

"No

one who loves life would wish to imitate her dedication to martyrdom."

The

bulk of Weil's writing was published only after her death from

tuberculosis in

1943. Gấu không nghĩ là cái tay “viết lại” Kẻ Xa Lạ và được Goncourt năm nay, hiểu được Camus. Tư tưởng của Camus, là từ Weil mà ra, (b) và Weil, như Susan Sontag, viết ở trên, cho rằng, chẳng ai dám bắt chước Weil, nếu kẻ đó còn yêu cuộc đời này! Bất giác lại nhớ tới lời

phẩm bình của vị thân hữu của TV. Vị này giải

thích,

Camus đẹp trai quá, “gái” nhiều quá, làm sao bắt chước cái khổ hạnh ghê

gớm như

của Weil! Có 1 cái gì

cực kỳ ngược ngạo, và hình như lại bổ túc cho nhau, giữa câu của Weil,

khi nhìn

những đoàn quân Nazi tiến vào Paris, và của TTT, khi nhìn VC Bắc Kít vô

Saigon. (b) Violent in

her judgments and uncompromising, Simone Weil was, at least by

temperament, an

Albigensian, a Cathar; this is the key to her thought. She drew extreme

conclusions from the Platonic current in Christianity. Here we touch perhaps

upon hidden ties between her and Albert Camus. The first work

by Camus was his

university dissertation on Saint Augustine. Camus, in my opinion, was

also a

Cathar, a pure one, and if he rejected God it was out of love for God

because

he was not able to justify Him. The last novel written by Camus, The

Fall, is

nothing else but a treatise on Grace-absent grace-though it is also a

satire:

the talkative hero, Jean-Baptiste Clamence, who reverses the words of

Jesus and

instead of "Judge not and ye shall not be judged" gives the advice

"Judge, and ye shall not be judged," could be, I have reasons to

suspect, Jean-Paul Sartre.  Susan Sontag Note: Bài viết

cách đây 50 năm, nhân kỷ niệm 50 năm NYRB, bèn cho đăng lại. Susan

Sontag không

đọc được Simone Weil. Cách nhìn của bà thua cả Gấu, đó là sự thực. Steiner,

Milosz, đọc Simone Weil, "đốn ngộ" hơn nhiều. Trên TV đã dịch bài của

Steiner. Gấu sẽ đi tiếp bài của Milosz, "Sự quan

trọng

của Simone Weil", in trong “To Begin Where I Am”. Trong cuốn này, có

mấy

bài thật là tuyệt. Bài essay, sau đây, chỉ cái tít không thôi, đã chửi

bố mấy đấng

VC đứng về phe nước mắt: Sontag chỉ

chịu nổi cuốn sau đây của Simone Weil:

The

principal value of the collection is simply that anything from Simone

Weil’s

pen is worth reading. It is perhaps not the book to start one’s

acquaintance

with this writer—Waiting for God, I

think, is the best for that. The originality of her psychological

insight, the

passion and subtlety of her theological imagination, the fecundity of

her

exegetical talents are unevenly displayed here. Yet the person of

Simone Weil

is here as surely as in any of her other books—the person who is

excruciatingly

identical with her ideas, the person who is rightly regarded as one of

the most

uncompromising and troubling witnesses to the modern travail of the

spirit. Co ai "noi nang" chi may bai cua Weil khg vay? Khg biet co ai kien nhan doc? Phúc đáp: Cần gì ai đọc! Tks. Take care. NQT * Bac viet phach loi nhu the nay - ky qua... * Thi phai phach loi nhu vay, gia roi. * Gia roi phai hien ma chet! Đa tạ. Nhưng, phách lối, còn thua xa thầy S: Ta là bọ chét! Phỏng Vấn Steiner Tuy cũng thuộc

băng đảng thực dân [mới, so với cũ, là Tẩy], nhưng

quả là Sontag không đọc ra, chỉ ý này, của

Steiner, trong Bad Friday: Với Weil, những

“tội ác” của chủ nghĩa thực dân có hồi đáp liền tù tì theo kiểu đối

xứng, cả về

tôn giáo và chính trị, với sự thoái hóa ở nơi quê nhà, tức “mẫu quốc”. Nhưng Bắc Kít,

giả như có đọc Weil, thì cũng thua thôi, ngay cả ở những đấng cực tinh

anh, là

vì nửa bộ óc của chúng bị liệt, đây là sự thực hiển nhiên, đừng nghĩ là

Gấu cường

điệu. Chúng làm sao nghĩ chúng cũng chỉ 1 thứ thực dân, khi ăn cướp

Miền Nam, vì

chúng biểu là nhà của chúng, vì cũng vẫn nước Mít, tại làm sao mà nói

là chúng ông

ăn cướp được. Chúng còn nhơ

bẩn hơn cả tụi Tẩy mũi lõ, tụi Yankee mũi lõ. Steiner còn

bài “Thánh Simone-Simone Weil”, trên TV cũng đã giới thiệu. For Weil, the "crimes" of colonialism related immediately, in both religious and political symmetry, to the degradation of the homeland. Time and again, a Weil aphorism, a marginalium to a classical or scriptural passage, cuts to the heart of a dilemma too often masked by cant or taboo. She did not flinch from contradiction, from the insoluble. She believed that contradiction "experienced right to the depths of one's being means spiritual laceration, it means the Cross." Without which "cruciality" theological debates and philosophic postulates are academic gossip. To take seriously, existentially, the question of the significance of human life and death on a bestialized, wasted planet, to inquire into the worth or futility of political action and social design is not merely to risk personal health or the solace of common love: it is to endanger reason itself. The two individuals who have in our time not only taught or written or generated conceptually philosophic summonses of the very first rank but lived them, in pain, in self-punishment, in rejection of their Judaism, are Ludwig Wittgenstein and Simone Weil. At how very many points they walked in the same lit shadows. Đối với Simone Weil, những “tội ác” của chủ nghĩa thực dân thì liền lập tức mắc míu tới băng hoại, thoái hóa, cả về mặt tôn giáo lẫn chính trị ở nơi quê nhà. Nhiều lần, một Weil lập ngôn – những lập ngôn này dù được trích ra từ văn chương cổ điển hay kinh thánh, thì đều như mũi dao - cắt tới tim vấn nạn, thứ thường xuyên che đậy bằng đạo đức giả, cấm kỵ. Bà không chùn bước trước mâu thuẫn, điều không sao giải quyết. Bà tin rằng, mâu thuẫn là ‘kinh nghiệm những khoảng sâu thăm thẳm của kiếp người, và, kiếp người là một cõi xé lòng, và, đây là Thập Giá”. Nếu không ‘rốt ráo’ đến như thế, thì, những cuộc thảo luận thần học, những định đề triết học chỉ là ba trò tầm phào giữa đám khoa bảng. Nghiêm túc mà nói, sống chết mà bàn, câu hỏi về ý nghĩa đời người và cái chết trên hành tinh thú vật hóa, huỷ hoại hoá, đòi hỏi về đáng hay không đáng, một hành động chính trị hay một phác thảo xã hội, những tra vấn đòi hỏi như vậy không chỉ gây rủi ro cho sức khoẻ cá nhân, cho sự khuây khoả của một tình yêu chung, mà nó còn gây họa cho chính cái gọi là lý lẽ.Chỉ có hai người trong thời đại chúng ta, hai người này không chỉ nói, viết, hay đề ra những thảo luận triết học mang tính khái niệm ở đẳng cấp số 1, nhưng đều sống chúng, trong đau đớn, tự trừng phạt chính họ, trong sự từ bỏ niềm tin Do Thái giáo của họ, đó là Ludwig Wittgenstein và Simone Weil. Đó là vì sao, ở rất nhiều điểm, họ cùng bước trong những khoảng tối tù mù như nhau. |