|

|

|

Nhà thơ nhà

nước Mẽo, đã từng đợp Pulitzer, nhưng còn là 1 dịch giả thần sầu. Gấu

thèm cuốn

này lâu rồi, bữa nay đành tậu về. Ông còn một cuốn dịch thơ haiku của

Buson, cũng

mới ra lò, 2013, Gấu cũng thèm lắm!

W. S. MERWIN

1927-

The

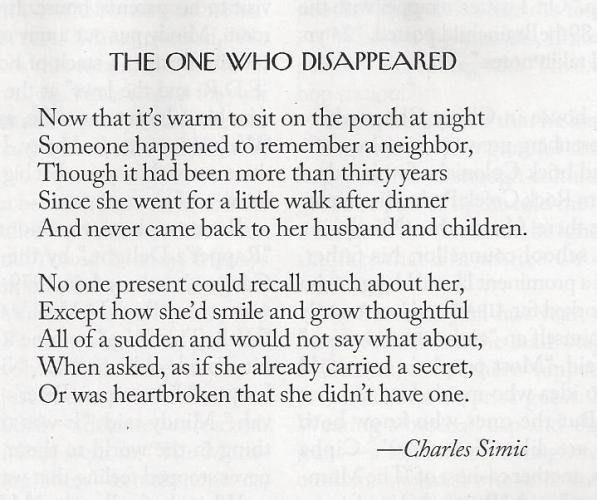

following poem inspires us to reflect on what seldom crosses our minds.

After all

(literally after all), such an anniversary awaits every one of us.

Bài thơ sau

đây gợi hứng cho chúng ta, về cái điều hiếm chạy qua đầu chúng ta.

Nói cho cùng, "kỷ niệm cái

chết của tôi" đâu bỏ quên, bất cứ ai?

Czeslaw

Milosz

FOR THE

ANNIVERSARY OF MY DEATH

Every year

without knowing it I have passed the day

When the

last fires will wave to me

And the

silence will set out

Tireless

traveler

Like the

beam of a lightless star

Then I will

no longer

Find myself

in life as in a strange garment

Surprised at

the earth

And the love

of one woman

And the

shamelessness of men

As today

writing after three days of rain

Hearing the

wren sing and the falling cease

And bowing

not knowing to what

Note:

Đọc,

thì cứ như là đang đọc, bài ai điếu GCC trên túi áo ngực bạn quí!

Chán thế!

EIN

FRAUEN-SCHICKSAL

So wie der

Konig auf der Jagd ein Glas

ergreift,

daraus zu trinken, irgendeines, -

und wie

hernach der welcher es besaf

es

fortstellt und verwahrt als war es keines:

so hob

vielleicht das Schicksal, durstig auch,

bisweilen

Eine an den Mund und trank,

die dann ein

kleines Leben, viel zu bang

sie zu

zerbrechen, abseits vom Gebrauch

hinstellte

in die angsrliche Vitrine,

in welcher

seine Kostbarkeiten sind

(oder die

Dinge, die fur kostbar gel ten).

Da stand sie

fremd wie eine Fortgeliehne

und wurde

einfach alt und wurde blind

und war

nicht kostbar und war niemals selten.

Rilke

WOMAN'S FATE

Just as the

king out on a hunt picks up

A glass to

drink from, anyone at all, -

and

afterward its owner puts it away

and guards

it like some fabled chalice:

So perhaps

Fate, who also thirsts, at times

Raised a

woman to its lips and drank,

whom then a

small life, too much afraid

of breaking

her, locked away from use

Inside the

tremulous glass cabinet

in which its

most precious things are kept

(at least

the things considered precious).

There she

stood strange like something loaned

and became

merely old and became blind

and was not

precious and was never special.

Số mệnh đờn

bà

Thì cứ kể như

là bữa đó, Trụ Vương đi săn bèn cầm 1 cái ly, từ bất cứ ai đó, lên uống

Thế là kẻ có

cái ly bèn kính cẩn đem cái ly về, nâng niu, coi như chén thánh

Có lẽ Số Mệnh,

cũng có 1 lần khát nước

Bèn nâng người đàn

bà lên môi và uống

Một người đàn

bà mới nhỏ nhoi làm sao

Và, như sợ làm

bể, bèn cất nàng vô 1 nơi, không dám đụng tới nữa

Trong căn lầu

vàng, nơi chứa toàn bảo vật vô giá

Có người đàn

bà, đứng đó, giống như 1 món đồ vay, mượn,

Già mãi đi, và

trở nên mù

Chẳng quí giá

cái con khỉ gì nữa, và chẳng đặc biệt cái chi chi!

Note:

Duyên Anh

có kể câu chuyện, về một cháu ngoan Bác Hồ, một bữa được Bác mi lên má,

bèn nhất

định không rửa mặt, sợ mất mùi Bác.

Nghe nói, cả tháng sau, cô bé con quyệt tay lên má, ngửi, khoe với bạn,

vưỡn

còn mùi Bác Hồ!

Đi tù cải tạo mút mùa vì chuyện này!

Hà, hà!

Thơ

Mỗi Ngày

Solitude

There now,

where the first crumb

Falls from

the table

You think no

one hears it

As it hits

the floor,

But

somewhere already

The ants are

putting on

Their Quaker

hats

And setting

out to visit you.

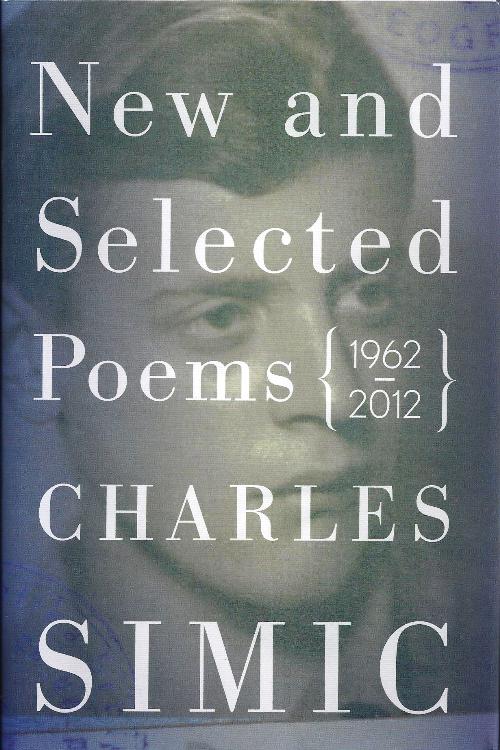

Charles

Simic: Selected Early Poems

Cô đơn

Chủ nhật, sáng

nay, ở một Starbucks, ở Tiểu Sài Gòn

Mẩu bánh sừng

trăng đầu tiên rớt khỏi mặt bàn em đang ngồi

Em nghĩ, chắc

là chẳng ai nghe tiếng rớt của nó, khi chạm sàn gỗ,

Nhưng đâu đó,

ở một thành phố khác

Đàn kiến đội lên đầu chiếc nón Quaker

Và lên đường,

thăm em giùm anh.

Emily's

Theme

My dear

trees, I no longer recognize you

In that

wintry light.

You brought

me a reminder I can do without:

The world is

old, it was always old,

There's

nothing new in it this afternoon.

The garden

could've been a padlocked window

Of a

pawnshop I was studying

With every

item in it dust-covered.

Each one of

my thoughts was being ghostwritten

By anonymous

authors. Each time they hit

A cobwebbed

typewriter key, I shudder.

Luckily,

dark came quickly today.

Soon the

neighbors were burning leaves,

And perhaps

a few other things too.

Later, I saw

the children run around the fire,

Their faces

demonic in its flames.

Charles

Simic

Nhã Đề

Cây thân

thương của ta ơi

Ta không còn

nhận ra mi

Trong cái ánh sáng hiu hắt này

Mi đem đến

cho ta lời nhắc nhở thật cần, nếu không có nó

Rằng thế giới

thì già, như nó vưỡn luôn luôn già

Chẳng có gì

mới trong nó, buổi xế trưa này

Khu vườn, vưỡn

như cái cửa sổ móc khóa

Của một tiệm

cầm đồ

Ta nghiên cứu

mọi món đồ đầy bụi của nó.

Mỗi một tư

tưởng của ta, thì đều được mướn viết

Bởi những

tác giả vô danh

Mỗi lần họ đập

một cú lên cái máy đánh chữ

Là ta rùng

mình, tim đau nhói một phát.

May quá, đêm,

bữa nay đến thật lẹ

Chẳng mấy chốc,

láng giềng sẽ đốt lá

Và có thể, một

vài cái gì nữa.

Sau đó, ta

nhìn thấy những đứa trẻ chạy vòng quanh

Mặt mũi

chúng phản chiếu trong ánh lửa ma mị

Thơ

Mỗi Ngày

Watermelons

Green

Buddhas

On the fruit

stand.

We eat the

smile

And spit out

the teeth.

Dưa Hấu

Phật xanh

Ngồi thành dẫy

Chúng ta đợp

nụ cười

Phun ra những cái răng

Poem Without

a Title

I say to the

lead,

"Why

did you let yourself

Be cast into

a bullet?

Have you

forgotten the alchemists?

Have you

given up hope

Of turning

into gold?"

Nobody

answers.

Lead.

Bullet.

With names

like that

The sleep is

deep and long .

Bài thơ vô đề

Tớ nói với

chì

Tại làm sao

mà mi lại để cho chúng đúc mi thành viên đạn?

Mi quên những

nhà luyện kim rồi ư?

Chẳng lẽ mi vứt bỏ hy vọng

Biến mình thành

vàng?

Đếch ai trả

lời.

Chì. Đạn

Với những

cái tên như thế

Giấc ngủ mới

sâu và dài làm sao.

Fork

This strange

thing must have crept

Right out of

hell.

It resembles

a bird's foot

Worn around

the cannibal's neck.

As you hold

it in your hand,

As you stab

with it into a piece of meat,

It is

possible to imagine the rest of the bird:

Its head

which like your fist

Is large,

bald, beakless, and blind.

Nĩa

Cái vật lạ

này hẳn là bò thẳng ra từ địa ngục

Nó giống như

chân chim

Đeo ở cổ 1

tên ăn thịt người

Bạn cầm

trong tay

Cắm vô miếng

thịt

Thật dễ tưởng

tượng ra phần còn lại của con chim.

Cái đầu của

nó thì có khác gì cú đấm của bạn,

Rộng, trọc,

không có mỏ, và mù.

Spoon

An old

spoon,

Chewed

And licked

clean,

Fixing you

With its

evil-eyed

Stare,

As you lean

over

The soup

bowl

On the

table,

To make sure

Once more

There is

nothing left.

Muỗng

Một cái muỗng

cũ

Nhai, liếm sạch

Với mắt quỉ

Chiếu tướng

bạn

Trong khi bạn

cúi xuống tô xúp trên bàn

Để chắc chắn

thêm một lần nữa

Đếch bỏ lại

1 thứ gì.

Charles

Simic

Thơ

Mỗi Ngày

The

Betrothal

I found a

key

In the

street, someone's

House key

Lying there,

glinting,

Long ago;

the one

Who lost it

Is not going

to remember it

Tonight, as

I do.

It was a

huge city

Of many dark

windows,

Columns and

domes.

I stood

there thinking.

The street

ahead of me

Shadowy,

full of peril

Now that I

held

The key. One

or two

Late

strollers

Unhurried

and grave

In view. The

sky above them

Of an

unearthly clarity.

Eternity

jealous

Of the

present moment,

It occurred

to me!

And then the

moment was over.

Charles

Simic

Hứa hôn

Gấu vớ được

một cái chìa khoá ở ngoài phố

Chìa khoá nhà

của một ai đó

Nằm đó, lấp

lánh

Lâu lắm rồi,

cái kẻ làm mất nó

Đã quên mẹ mất

nó

Không như Gấu,

tối nay

Đó là một thành

phố rộng

Với nhiều cửa

sổ tối

Những cây cột,

những cái vòm

Gấu đứng đó,

nghĩ linh tinh

Con phố trước

mặt Gấu

Âm u với những bóng tối của nó, đầy rủi ro, bất trắc

Vào lúc này,

Gấu giữ cái chìa khóa

Một, hai khách

bộ hành, muộn

Không hối hả, trầm trọng

Trong tầm nhìn

của Gấu

Bầu trời bên

trên họ

Sáng sủa cách

gì đâu, một cách “không trần thế”

Vĩnh cửu

ghen với Gấu Cà Chớn, tối nay.

Ghen với cái

khoảnh khắc hiện tại thần sầu

Xẩy ra cho Gấu, chỉ cho Gấu!

Và

rồi, khoảnh

khắc thần tiên, đếch còn nữa!

Death, the

Philosopher

He gives

excellent advice by example.

"See!"

he says. "See that?"

And he

doesn't have to open his mouth

To tell you

what.

You can

trust his vast experience.

Still,

there's no huff in him.

Once he had

a most unfortunate passion.

It came to

an end.

He loved the

way the summer dusk fell.

He wanted to

have it falling forever.

It was not

possible.

That was the

big secret.

It's

dreadful when things get as bad as that-

But then they don't!

He got the point,

and so, one day,

Miraculously lucid, you, too, came to ask

About the strangeness of it all.

Charles, you

said,

How strange

you should be here at all!

Charles

Simic

Thần Chết,

Thầy Triết

Hắn đưa ra lời

khuyên thần sầu, bằng thí dụ.

“Thấy không!”

hắn nói. “Thấy cái đó không”?

Và hắn không

phải há miệng ra, để nói, “what” là cái đéo gì với bạn.

Bạn có thể

tin vào kinh nghiệm rộng của hắn.

Tuy nhiên, đếch

có cái gọi là giận dữ ở hắn ta, Thần Chết, Thầy Triết.

Có thời, hắn

có cái đam mê bất hạnh nhất

Nó cạn láng

từ khuya.

Hắn yêu, cái

cách mà hoàng hôn mùa hè té xuống

Hắn muốn nó

cứ té như thế, thiên thu, hoài hoài.

Nhiệm vụ bất

khả thi!

Đó là bí mật

lớn

Thật đáng sợ

khi sự vật tệ hại đến mức như thế -

Nếu như thế,

thì, đừng!

Hắn phản biện

OK, được 1 điểm - đúng không, và thế là, có một ngày

Cực kỳ sáng suốt,

như 1 phép lạ

Bạn, chính bạn,

cũng tới gặp, xin 1 lời cố vấn

Về cái sự lạ

lùng của tất cả ba cái lẩm cẩm đó

Gấu Cà Chớn,

bạn phán,

Lạ lùng làm

sao, thứ như mi, mà cũng có mặt ở trên cõi đời này!

Thơ

Mỗi Ngày

J'AI EU LE

COURAGE ...

J'ai eu le

courage de regarder en arrière

Les cadavres

de mes jours

Marquent ma

route et je les pleure

Les uns

pourrissent dans les églises italiennes

Ou bien dans

de petits bois de citronniers

Qui fleurissent

et fructifient

En même

temps et en toute saison

D'autres

jours ont pleuré avant de mourir dans des tavernes

Ou d'ardents

bouquets rouaient

Aux yeux

d'une mulâtresse qui inventait la poésie

Et les roses

de l'électrécité s’ouvrent encore

Dans le

jardin de ma mémoire

Guillaume Apollinaire

I HAD THE

COURAGE...

J' ai eu le

courage. .

I had the

courage to look backward

The ghosts

of my days

Mark my way

and I mourn them

Some lie

moldering in Italian churches

Or in little

woods of citron trees

Which flower

and bear fruit

At the same

time and in every season

Other days

wept before dying in taverns

Where ardent

odes became jaded

Before the

eyes of a mulatto girl who inspired poetry

And the

roses of electricity open once more

In the

garden of my memory

DAISY ALDAN

French Poetry,

edited by Angel Flore, introduction by Patti Smith, Anchor Books

FROM

"LES FIANCAILLES"

to Picasso

I have had

the courage to look back

At the dead

bodies of my days

They litter

the roads I've taken and I miss them

That's me

rotting in so many Italian churches

And in the

nearby lemon groves

Which flower

and produce little lemons

Also and in

every season

Other days

died weeping late at night in a bar

Where

bouquets of dazzle spun around

In the eyes

of a mulatto woman who invented poetry

The roses of

electricity open even now

In the garden

of my memory

- Translated

from French by the Editors

[The Paris

Review, Fall 2012]

In a Dark

House

One night,

as I was dropping off to sleep,

I saw a

strip of light under a door

I had never

noticed was there before,

And both

feared and wanted

To go over

and knock on it softly.

In a dark

house, where a strip of light

Under a door

I didn't know existed

Appeared and

disappeared, as if they

Had turned

off the light and lay awake

Like me

waiting for what comes next.

Charles

Simic: New Poems

Trong Căn Nhà

Tối

Một đêm, tôi

lơ mơ tính ngủ

Bỗng nhìn thấy

một mảnh ánh sáng bên dưới cửa

Tôi chưa từng

để ý đến, trước đó

Và vừa sợ, lại

vừa muốn

Tôi bèn tới

nhìn, và gõ nhè nhẹ lên nó

Nơi căn nhà

tối, bỗng dưng 1 mảnh sáng dưới cửa

Tôi không hề

biết, nó có

Xuất hiện rồi

biến mất

Như thể họ tắt

mẹ đèn đóm

Và nằm thức,

chờ

Như tôi

Coi cái gì sẽ

xẩy ra,

Tiếp, tới.

Lingering

Ghosts

Give me a

long dark night and no sleep,

And I'll

visit every place I have ever lived,

Starting

with the house where I was born.

I'll sit in

my parents' dimmed bedroom

Straining to

hear the tick of their clock.

I'll roam

the old neighborhood hunting for friends,

Enter

junk-filled backyards where trees

Look like

war cripples on crutches,

Stop by a

tree stump where Grandma

Made

roosters and hens walk around headless.

A black cat

will slip out of the shadows

And rub

herself against my leg

To let me

know she'll be my guide tonight

On this

street with its missing buildings,

Missing

faces and few lingering ghosts.

Charles

Simic: New Poems

Những hồn

ma dai dẳng.

Cho tớ 1 đêm

đen dài và đếch làm sao ngủ được

Và tớ sẽ về

thăm mọi chỗ tớ đã từng sống

Bắt đầu bằng

ngôi nhà tớ sinh ra

Tớ sẽ ngồi

trong căn phòng lù mù của ông bà già

Cố nghe cho được

tiếng tích tắc của cái đồng hồ ngày nào của họ

Tớ sẽ đảo

qua đảo lại khu lối xóm

Săn tìm lũ bạn

cũ

Đi vô những

sân sau tạp nhạp

Cây, như những thương binh què quặt

Đi ngang một

gốc cây

Nơi Bà tớ

thường dẫn đàn gà,

Không đầu đi dạo

Một con mèo đen

từ trong những bóng đêm vọt ra

Cọ cọ vào chân

tớ

Như muốn nói,

ta sẽ là kẻ dẫn đường cho mi

Về thăm lại

quê hương cũ đêm nay

Trên con phố

với những tòa nhà thèm nhớ,

Những khuôn

mặt thèm nhớ

Và những hồn

ma dai dẳng.

To Fate

You were

always more real to me than God.

Setting up

the props for a tragedy,

Hammering

the nails in

With only a

few close friends invited to watch.

Just to be

neighborly, you made a pretty girl lame,

Ran over a

child with a motorcycle.

I can think

of many other examples

Ditto: How

the two of us keep meeting

A

fortunetelling gumball machine in Chinatown

May have the

answer,

An old

creaky door opening in a horror film,

A pack of

cards I left on a beach.

I can feel

you snuggle close to me at night,

With your

hot breath, your cold hands-

And me

already like an old piano

Dangling out

of a window at the end of a rope.

Gửi Số Phần

Với tớ, mi thực

hơn, so với Ông Giời

Trong cái trò

tạo dựng ra sân khấu chơi 1 bi kịch

Nhất là cú đóng đinh

Với chỉ vài

đấng bạn, cực thân, cực quí được mời coi.

Chỉ là tình lối

xóm, mi làm cho một thiếu nữ xinh đẹp, què

Chạy xe máy

và cán lên 1 đứa trẻ.

Tớ có thể

nghĩ đến nhiều thí dụ khác nữa

Như trên: Làm

thế nào hai đứa chúng ta tiếp tục gặp.

Cái máy

gumball kể chuyện may rủi ở Chinatown

Có lẽ có câu

trả lời

Cái cửa

cũ ọp ẹp mở vô 1 một kinh dị

Cỗ bài tớ

bỏ trên bãi biển.

Tớ có thể cảm thấy, mi mò

lại

gần tớ, vào ban đêm

Với hơi thở

nóng bỏng, bàn tay lạnh ngắt –

Và tớ thì như cây dương cầm cũ

Lủng lẳng bên

ngoài cửa sổ, cuối một sợi dây.

Charles

Simic

Cuộc

tàn sát

những kẻ vô tội

Những nhà thơ Hậu Đường

Đâu có làm gì

được, ngoài cái việc đi 1 đường Facebook, sau đây:

"Ở những ngọn

đồi phía Tây, mặt trời lặn…

Những con ngựa

bị gió thổi, dẫm lên những đám mây."

Tớ cũng đếch

làm gì được ở đây.

Nhưng quái làm sao,

tớ thấy vui

Ngay cả trên

đầu tớ,

Một chú quạ

bay vòng vòng.

Trong lúc tớ

thả mình xuống lớp cỏ,

Một mình với

cái im lặng của bầu trời

Chỉ có gió, là rì rào nhè

nhẹ

Lật những

trang của cuốn sách ở bên tớ

Lật tới lật

lui, như kiếm cái con khỉ gì

Cho con quạ

máu me đọc.

The Massacre

of the Innocents

The poets of

the Late Tang Dynasty

Could do

nothing about it except to write:

"On the

western hills the sun sets ...

Horses blown

by the whirlwind tread the clouds."

I could not

help myself either. I felt joy

Even at the

sight of a crow circling over me

As I

stretched out on the grass

Alone now

with the silence of the sky.

Only the

wind making a slight rustle

As it turned

the pages of the book by my side,

Back and

forth, searching for something

For that

bloody crow to read.

Charles

Simic: A Wedding in Hell

THE

REVOLUTION HAS ENDED

REMEMBERING

JULIAN KORNHAUSER'S

MOURNFUL

REVOLUTIONARIES

The

revolution has ended. In the parks pedestrians

marched

slowly, dogs traced perfect circles,

as if guided

by an unseen hand.

The weather

was lovely, rain like diamonds,

women in

summer dresses, children as always

slightly

peeved, peaches on tabletops.

An old man

sat in a cafe and cried.

Sports car

motors roared,

newspapers

shrieked, and essentially,

it should be

said,

life

revealed ascendant tendencies

-to employ a

neutral definition,

thus

wounding neither victors nor the vanquished,

or those who

still didn't know

which side

they were on,

that is, in

effect, all of us

who write or

read these words.

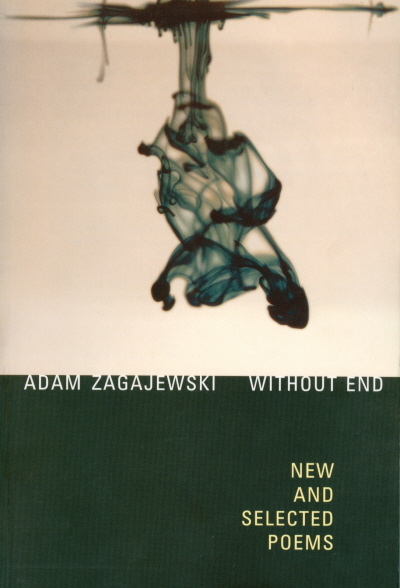

Adam

Zagajewski

Cách Mạng Chấm

Dứt

Tưởng nhớ những

nhà cách mạng sầu thảm

của JULIAN

KORNHAUSER

Cách mạng chấm

dứt. Ở công viên, bộ hành,

bước chầm chậm,

những con chó vẽ những vòng tròn tuyệt hảo

như được dẫn

dắt bởi một bàn tay không nhìn thấy

Thời tiết thật

đáng yêu

Mưa rơi như

kim cương

Phụ nữ trong

áo hè, con nít càu nhàu tí tí,

chúng luôn

thế, những trái đào trên mặt bàn.

Một ông già

ngồi trong quán cà phê, và la khóc.

Xe hơi thể

thao, xe gắn máy gầm rú

Nhật báo la

bai bải, chủ yếu muốn nói,

đời bi giờ

là vinh quang, đỉnh cao

– dùng những

từ chung chung, để khỏi làm đau lòng

kẻ thắng

cũng như người bại,

hay họ ở bên

nào Cách Mạng hay là Ngụy,

Họ, có nghĩa

là, tất cả chúng ta

Những người

viết, hay đọc những dòng này.

SELF-PORTRAIT

IN BED

For

imaginary visitors, I had a chair

Made of cane

I found in the trash.

There was a

hole where its seat was

And its legs

were wobbly

But it still

gave a dignified appearance.

I myself

never sat in it, though

With the

help of a pillow one could do that

Carefully,

with knees drawn together

The way she

did once,

Leaning back

to laugh at her discomfort.

The lamp on

the night table

Did what it

could to bestow

An air of

mystery to the room.

There was a

mirror, too, that made

Everything

waver as in a fishbowl

If I

happened to look that way,

Red-nosed,

about to sneeze,

With a thick

wool cap pulled over my ears,

Reading some

Russian in bed,

Worrying

about my soul, I'm sure.

Charles

Simic

[From My

Noiseless Entourage, 2005]

Chân Dung Tự

Họa ở trên Giường

Với mấy đấng

bạn quí, tưởng tượng

Gấu có 1 cái

ghế

Làm bằng ba

cái lon

Lấy từ thùng

rác

Có 1 cái lỗ,

đúng ngay chỗ để bàn tọa

Mấy cái chân

ghế lung lay như răng bà lão

Tuy nhiên,

nhìn cái ghế, vưỡn thấy có tí gì phẩm giá của riêng nó

Gấu, chính Gấu,

chẳng hề dám ngồi lên

Nhưng, với 1

cái gối, thì chuyện ngồi có thể

Với 1 tí cẩn

trọng, tất nhiên

Hai đầu gối

phải níu lấy nhau

Đúng là cách

mà H/A đã từng, một lần

Em ngả đầu

ra phía sau, cười

Che giấu sự

mất thoải mái của mình

Cây đèn bàn

ngủ

Làm cái điều

phải làm

Nghĩa là

Ban cho căn

phòng vẻ bí ẩn.

Một cái gương

nữa chứ

Nó làm cho cảnh

vật lung linh

Như trong 1

chậu cá cảnh

Nếu nhìn

theo viễn ảnh như thế đó

Mũi đỏ

lòm, thèm

xụt xịt vài cú

Với cái

mũ

len chùm kín cả tai

Gấu nằm

trên

giường

Đọc Dos,

Lơ tơ mơ

về

linh hồn của mình

Hẳn thế.

Past-Lives

Therapy

They showed

me a dashing officer on horseback

Riding past

a burning farmhouse

And a

barefoot woman in a torn nightgown

Throwing

rocks at him and calling him Lucifer,

Explained to

me the cause of bloody bandages

I kept

seeing in a recurring dream,

Cured the

backache I acquired bowing to my old master,

Made me stop

putting thumbtacks round my bed.

When I was a

straw-headed boy in patched overalls,

Chickens

would freely roost in my hair.

Some laid

eggs as I played my ukulele

And my

mother and father crossed themselves.

Next, I saw

myself in an abandoned gas station

Trying to convert

a coffin into a spaceship,

Hoarding

dead watches in a house in San Francisco,

Spraying

obscenities on a highway overpass.

Some days,

however, they opened door after door,

Always to a

different room, and could not find me.

There'd be a

small squeak now and then in the dark,

As if a

miner's canary just got caught in a mousetrap.

Chữa bịnh kiếp

trước, kiếp trước nữa

Kiếp trước ta

có nợ nần chi mi đâu

Mà sao kiếp

này mi đòi kiếp khác?

Ta đã nói mi

đừng gặp ta nhiều

Khi ta đi rồi

Mi sẽ khổ

NQT: Chiều

ngu ngơ phố thị

Họ chỉ cho tớ

1 tên sĩ quan phóng ngựa như bay

Qua 1 căn nhà

trại đang cháy

Một người đàn

bà chân trần, mặc áo ngủ rách tả tơi

Ném đá vào tên

sĩ quan, gọi hắn là Quỉ Sứ

Giải thích

những tấm băng dính máu

Trong giấc mơ

trở đi trở lại hoài

Chữa chứng đau

lưng, do lạy vị thầy cũ hơi bị nhiều

Làm cho tớ hết

còn bị chơi cái trò rải đinh bấm quanh giường.

Khi còn là 1

đứa bé đầu tóc như mớ rơm

Lũ gà cứ tìm

đầu tớ để ngủ

Có con còn đẻ

trứng khi tớ chơi đàn bốn dây

Trong khi ông

bô bà bô xẹo qua xẹo lại

Kế đó, tớ

thấy mình ở 1 cái trạm xăng bỏ hoang

Cố biến cái

hòm thành cái phi thuyền

Tích trữ đồng

hồ chết trong 1 căn nhà ở San Francisco

Xịt ba từ tục

tĩu lên cầu xa lộ

Tuy nhiên, vài

ngày đẹp trời, họ mở hết cửa này tới cửa kia

Luôn trổ ra

1 căn phòng khác, và đếch kiếm thấy tớ

Luôn có tiếng

cọt kẹt lúc này hoặc lúc khác trong bóng tối

Như thể 1

con chim hoạ mi của 1 tay thợ mỏ bị mắc cái bẫy chuột

History

On a gray

evening

Of a gray

century,

I ate an

apple

While no one

was looking.

A small,

sour apple

The color of

wood fire

Which I

first wiped

On my sleeve.

Then I

stretched my legs

As far as

they'd go,

Said to

myself

Why not

close my eyes now

Before the

late

World News

and Weather.

Charles

Simic

Lịch sử

Vào một buổi

chiều xám

Thế kỷ xám

Gấu xực 1 trái

táo

Khi không ai

nhìn

Một trái táo

nhỏ

Chua ơi là

chua

Màu lửa củi

Gấu lấy tay áo

lau miệng

Rồi, ruỗi cẳng

ra

Mặc sức chúng

ruỗi

Rồi Gấu nói

với Gấu

Tại sao mi không nhắm mắt lúc này

Trước bản

tin trễ

Tin thế giới

và thời tiết

Thu 2014

L'adieu

Apollinaire

(1880-1918)

J'ai cueilli

ce brin de bruyère

L'automne

est morte souviens-t'en

Nous ne

nous

verrons plus sur terre

Odeur du

temps brin de bruyère

Et

souviens-toi que je t'attends

The

Farewell

I picked this fragile sprig

of heather

Autumn has died long since remember

Never again shall we see one another

Odor of time sprig of heather

Remember I await our time together

Translated from the French by Roger Shattuck

[Time of

Grief]

Rilke

Robert Hass

SEPTEMBER 19

Rainer Maria

Rilke: Herbsttag

Rainer Maria

Rilke is one of the great poets of the twentieth century. He's also

one of the most popular. He's been translated again and again, as if

some ideal

English version of his German poems haunted so many minds that writers

have had

to keep trying to find it. Here, for the time of year, are some

translations of

a poem about the fall. He wrote it in Paris on September 21, 1902.

Autumn Day

Rilke là 1

trong những nhà thơ lớn của thế kỷ 20. Ông cũng là 1 nhà thơ phổ thông.

Ông được

dịch đi dịch lại, như thể, những bài thơ tiếng Đức của ông ám ảnh rất

nhiều cái

đầu, và những nhà văn phải cố tìm cho thấy nó. Đây là bài thơ cho mùa

thu năm

nay, với cả 1 lố bản dịch.

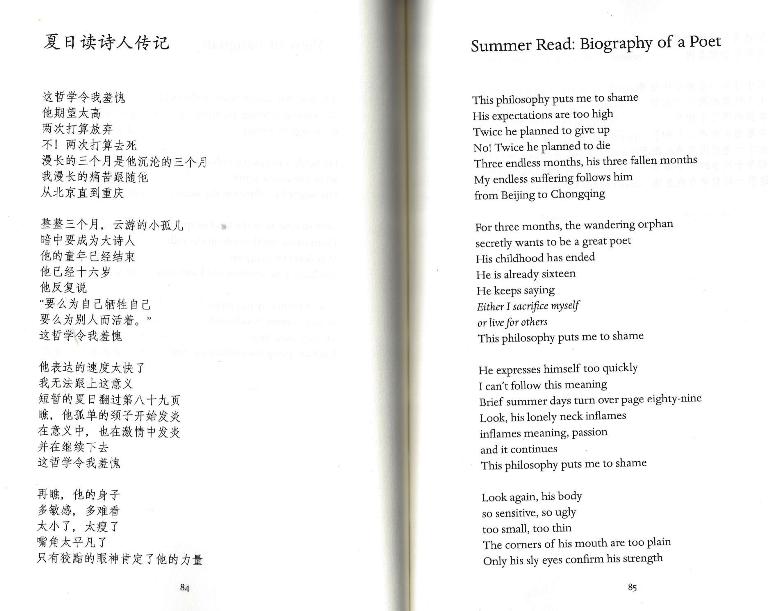

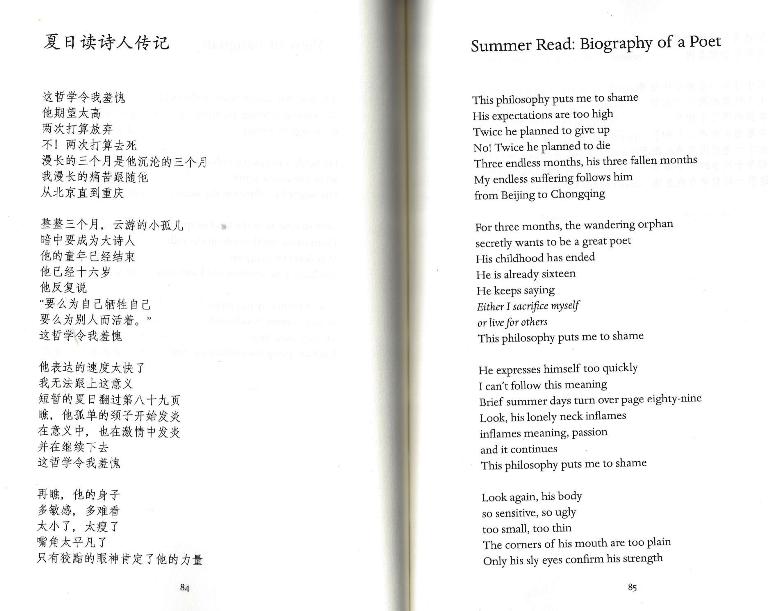

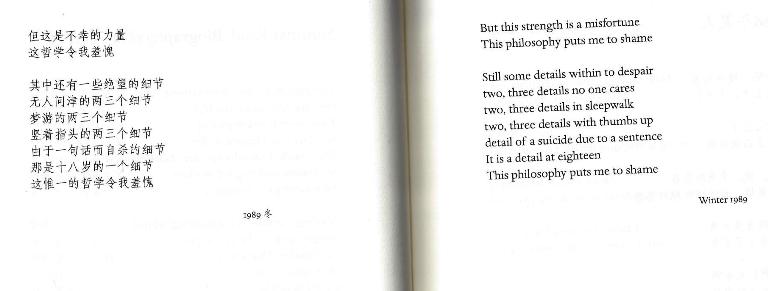

Đọc Hè: Tiểu

sử một thi sĩ

Thứ triết này

khiến tôi tủi hổ

Trông mong của

anh ta hơi bị cao

Hai lần anh tính chịu thua

Không! Hai lần, tính chết

Ba tháng đằng

đẵng, ba tháng suy sụp của anh

Nỗi đau dài

dài của tôi theo anh

Từ Beijing tới

Chongqing

Ba tháng,

anh chàng mồ côi lang thang

Âm ỉ, kín đáo

muốn trở thành một nhà thơ lớn

Tuổi thơ của

anh ta chấm dứt

Anh ta đã mười

sáu tuổi

Anh ta luôn

luôn nói

Hoặc là tôi

làm thịt chính tôi

Hay sống cho

những người khác

Thứ triết này khiến tôi tủi hổ, nhục nhã

Anh ta biện

về anh nhanh, cực nhanh

Tôi không làm

sao theo kịp

Những ngày hè

ngắn ngủi mở tới trang tám-chín

Nhìn kià, vấng trán cô đơn của anh bốc lửa

Bốc lửa ý

nghĩa, bốc lửa tham vọng

Và nó cứ thế

tiếp tục

Thứ triết này làm tôi tởm

Nhìn nữa này,

cơ thể của anh ta

Thật vãi lệ,

thật xấu xa

Góc miệng của

anh ta quá bèn bẹt

Chỉ cặp mắt ranh

mãnh, láu cá chó

Chứng thực sức mạnh của anh ta

Nhưng sức mạnh

thì có khác gì bất hạnh, cái rủi, vận xấu

Thứ triết này khiến tôi tủi hổ.

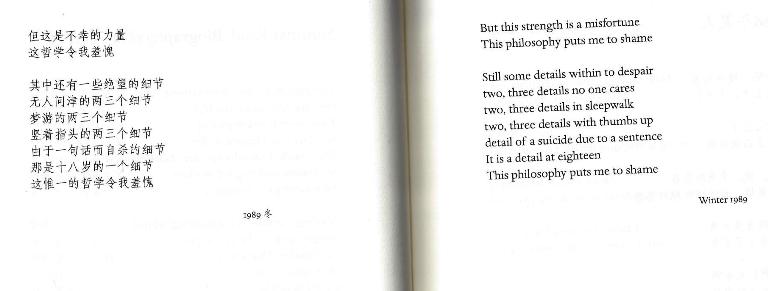

Tuy nhiên,

vưỡn có vài chi tiết nội, khiến chán chường

Hai, ba chi

tiết đếch ai cần

Hai, ba chi

tiết khi mộng du

Hai, ba chi

tiết với ngón cái trỏ lên

Chi tiết lần

tự tử là từ 1 câu văn

Một chi tiết

thời mười tám

Thứ triết này khiến tôi nhục nhã.

Mùa Đông

1989

Ui chao đọc

bài thơ thì lại nhớ tới thứ văn chương tục tĩu của đám phản kháng, ly

khai, ở

trong nước. Cả ở hải ngoại cũng có thứ này, nhưng do lý do khác.

Cực tởm. Hơi

1 tí, là chúng văng của quí ra.

Nothing Else

Friends of

the small hours of the night:

Stub of a

pencil, small notebook,

Reading lamp

on the table,

Making me

welcome in your circle of light.

I care

little the house is dark and cold

With you

sharing my absorption

In this book

in which now and then a sentence

Is worth

repeating in a whisper.

Without you,

there'd be only my pale face

Reflected in

the black windowpane,

And the bare

trees and deep snow

Wailing for

me out there in the dark.

H/A thôi, đủ

rồi

Bạn của những

giờ nhỏ trong đêm:

Mẩu viết chì,

cuốn sổ nhỏ

Đèn bàn

Chúng chào anh

khi nhập vô vòng ánh sáng quanh em

Anh không để

ý gì nhiều về căn nhà thì tối và lạnh

Với em cùng

nhập vô cuốn sách

Lúc này, hay

lúc nọ, một câu văn

Thì thật đáng

lập lại trong lời thầm

Không có

em,

sẽ chỉ có bộ mặt lợt lạt của anh

Phản chiếu

trong khung cửa tối

Và cây trần,

tuyết sâu

Đợi anh ở bên

ngoài, trong bóng đêm.

Thơ

Mỗi Ngày

Hàng mới về!

TRẦN HỮU

HOÀNG

TÌM BÓNG

Một đời đi

tìm bóng

Một đời đi

tìm nhau

Đôi ta như

ngọn sóng

Tìm nhau rồi

mất nhau

Tôi tìm tôi

mất dấu

Trong ngấn lệ

của em

Đêm lung

linh thạch thảo

Đàn thu lạnh

bên thềm

Em trao tôi

giọng hát

Tim rộn bước

ngày về

Ôi ngày về

cháy khát

Trong tiếng

nhạc hồn quê

Một đời đi

tìm bóng

Một đời đi

tìm nhau

Sóng vỗ về

trông ngóng

Bạc đầu mà

nhớ nhau

6/2005

Tán nhảm.

1. Bài thơ

này làm Gấu nhớ tới một bài thơ của... Gấu. "Sóng vỗ về trông ngóng"

làm nhớ khổ thơ:

Đêm mở ra giấc

mộng cũ

Chỉ có tôi,

tôi, và tôi

Cô bạn thân

ơi, nẻo về tuyệt lối

Hồn tôi điên

cuồng réo gọi.

Thơ NQT

"Vỗ về

trông ngóng" mềm hơn nhiều, so với "điên cuồng réo gọi!.

2.

Bạc đầu mà nhớ

nhau

Chữ “mà” này

thật lạ. Và cũng thật đắt.

Thử... gia

giảm.

Bạc đầu

còn nhớ nhau

Bạc đầu

vì nhớ nhau...

Nhưng, nhảm

nhất là tứ này:

Bạc đầu vì

chán nhau!

Gấu

[To THH:

Sorry. NQT]

THE IMMORTAL

You're

shivering, O my memory.

You went out

early and without a coat

To visit

your old schoolmasters,

The cruel

schoolmasters and their pet monkeys.

You took a

wrong turn somewhere.

You met an

army of gray days,

A ghost army

of years on the march.

It was the

bread they fed you,

The kind it

takes a lifetime to chew.

You found

yourself again on that street

Inside that

small, rented room

With its

single dusty window.

Outside it

was snowing quietly,

Snowing and

snowing for days on end.

You were ill

and in bed.

Everyone

else had gone to work.

The blind

old woman next door,

Whose sighs

and heavy steps you'd welcome now,

Had died

mysteriously in the summer.

You had your

own heartbeat to attend to.

You were perfectly

alone and anonymous.

It would

have taken months for anyone

To begin to

miss you. The chill

Made you

pull the covers up to your chin.

You

remembered the lost arctic voyagers,

The evening

snow erasing their footprints.

You had no

money and no job.

Both of your

lungs were hurting; still,

You had no

intention of lifting a finger

To help

yourself. You were immortal!

Outside, the

same dark snowflake

Seemed to be

falling over and over again.

You studied

the cracked walls,

The maplike

water stain on the ceiling,

Trying to

fix in your mind its cities and rivers.

Time had

stopped at dusk.

You were

shivering at the thought

Of such

great happiness.

Charles

Simic

Kẻ bất tử

Mi rùng mình

ư, ôi hồi ức khốn khổ của ta ơi

Mi đi ra

ngoài khi trời còn tối thui và

Cũng chẳng

thèm mặc thêm cái áo khoác

Thăm mấy ông

thầy độc ác của mi,

Với những

con khỉ cưng của họ

Mi quẹo lộn

đường ở một khúc nào đó.

Mi gặp một đạo

quân của những ngày xám xịt

Một đội quân

ma của những năm, đang diễn hành.

Chúng ban

cho mi khúc bánh mì

Thứ bánh mi bỏ

cả đời để gặm.

Mi lại thấy

mi ở con phố đó

Bên trong 1

căn phòng thuê, nhỏ.

Với trần cái

cửa sổ, một cánh, bụi bặm

Bên ngoài tuyết

rơi lặng lẽ

Rơi, rơi

theo những ngày dài lê thê cho đến vãn tuồng.

Mi bịnh, nằm

trên giường.

Mọi người phải

đi làm.

Bà già mù

phòng kế bên

Vào lúc này,

mi mừng rơn,

Khi nghe bước

chân nặng nề, và tiếng thở dài của bà,

Đã

mất một cách bí ẩn mùa hè

Mi

có tiếng đập tim của chính mi, để chăm sóc

Mi hoàn toàn minh ên, và vô danh tiểu tốt

Phải mất hàng tháng may ra mới có người cảm thấy nhớ

mi.

Cơn lạnh làm mi kéo mền lên tới tận cằm

Mi

có nhớ những nhà du ngoạn Bắc Cực

Tuyết buổi chiều xóa sạch những vết chân của họ

Mi chẳng có hồi ức, đếch có việc làm

Cả hai lá phổi của mi thì đều thủng, giờ này tất nhiên,

vưỡn còn.

Mi chẳng hề có ý định nhắc ngón tay, để tự cứu

Mi thì bất tử!

Bên

ngoài vẫn tuyết đó,

Những cánh tuyết xám

Lại rơi rơi

Mi nghiền ngẫm những bức tường nứt

Vệt nước trên trần nhà

Như cái bản đồ

Mi cố vẽ ra những sông, núi và những thành phố của nó

Ở trong cái đầu của mi.

Thời

gian ngưng vào lúc xẩm tối

Mi rùng mình khi nghĩ đến,

Ôi chao, một thứ hạnh phúc như thế đó.

Robespierre

Who

wouldn’t

like to have the power to kill

Friends and

enemies at will and fill

The jails

with people you don’t know or know

Only

slightly from meeting them a year ago,

Maybe at an

AA meeting, where they don’t even use last names.

Hi, I’m

Fred. Instead of being someone who constantly blames

And

complains, why not annihilate?

Why not

hate? Why not exterminate? Why not violate

Their rights

and their bodies? Tell

The truth.

Who wouldn’t like to? There’s a wishing well in hell

Where every

wish is granted.

Decapitation

gets decanted.

Suppose you

have the chance

To

guillotine the executioner after having guillotined everyone else in

France?

Robespierre

Ai mà chẳng thèm

- nhất là anh cu Gấu – làm thịt thỏa thích, vô tư

Bạn quí

& kẻ thù [cũng 1 thứ, hà, hà!]

Và nhét chật

nhà tù, những kẻ không quen biết, hay chỉ mới nhìn thoáng qua, cỡ 1 năm

trước,

Có thể lần ở

AA, nơi không ai dùng đến, ngay cả tên của mình

Hi, tớ là Khánh

[đúng ra, phải là Lý Khanh, thí dụ]

Thay vì càu

nhàu, lầu bầu, dọn mới chả dọn, thì huỷ diệt, biến bạn quí thành mây

thành khói,

cũng theo hư không mà đi!

Tại sao không

thù hận? Tại sao không huỷ diệt, làm cỏ? Tại sao không vi phạm quyền

hạn và thân

thể của họ?

Hãy nói sự

thực. Ai không muốn điều này? Có cái 1 cái giếng ước muốn, ở địa ngục

Thề, thay vì

phanh thây, uống máu, thì là, chặt đầu!

Giả như bạn

có cơ hội

Chặt đầu kẻ

chặt đầu sau khi chặt đầu mọi người ở xứ Tẩy?

Nina

Cassian, a Romanian-born poet exiled in New York, died on April 14th,

aged 89

With

rational syllables

I try to

clear up the occult mind

and

promiscuous violence.

My

linguistic protest has no power

The enemy is

illiterate.

No poets

leave their language or country of their own free will, she said. She

missed

her native tongue’s licentiousness:

...the

clitoris in my throat

vibrating,

sensitive, pulsating,

exploding in

the orgasm of Romanian.

Like her

great émigré counterparts, the Russian Joseph Brodsky and the Pole

Czeslaw

Milosz, she eventually began to write in English, adding poignant notes

of

exile to her themes of honesty, humour and eroticism. Initially she

felt

trapped by the strangeness of American life, especially the

materialism. But in

1998 she married again, to her great happiness. She always found the

American

literary scene a bit odd (she wrote sardonic lines about the plonkish

practice

of summarising poems before reading them in public). But she pitched in

gladly,

adding her voice to a campaign for politeness on the subway.

I stood

during the entire journey:

nobody

offered me a seat

although I

was at least a hundred years older than anyone else on board,

although the

signs of least three serious afflictions were visible on me:

Pride,

Loneliness, and Art.

She felt

unwelcome in post-revolutionary Romania: censorship ended after 1989,

but

censoriousness was rife. People said her life under communism had been

too

privileged, and she had run away to the West, escaping the regime’s

worst,

final years. She was unbothered: everyone makes mistakes, she said. You

just

had to be honest about them.

Thơ Mỗi Ngày

Paradise

Motel

Millions

were dead; everybody was innocent.

I stayed in

my room. The President

Spoke of war

as of a magic love potion.

My eyes were

opened in astonishment.

In a mirror

my face appeared to me

Like a

twice-canceled postage stamp.

I lived

well, but life was awful.

there were

so many soldiers that day,

So many

refugees crowding the roads.

Naturally,

they all vanished

With a touch

of the hand.

History

licked the corners of its bloody mouth.

On the pay

channel, a man and a woman

Were trading

hungry kisses and tearing off

Each other's

clothes while I looked on

With the

sound off and the room dark

Except for

the screen where the color

Had too much

red in it, too much pink.

Charles

Simic

Phòng Ngủ

Thiên Đàng

Ba triệu Mít

chết

Mọi Mít đều ngây thơ,

Đếch tên nào có tội

Gấu ngồi

trong phòng

Ba Dzũng, Tông Tông Mít,

Giao liên

VC, y tá dạo ngày nào

Lèm bèm về

Cuộc Chiến Mít

Như về Thần

Dược Sex

Gấu trợn mắt,

kinh ngạc

Trong gương, Gấu nhìn Gấu

Chẳng khác gì

một con tem bị phế thải tới hai lần

Gấu sống được,

nhưng đời thì thật là khốn nạn

Ngày đó đó, đâu

đâu cũng thấy lính

Ui chao Mít di tản đầy

đường

Lẽ tất nhiên tất cả biến

mất,

Chỉ nhìn thấy bóng dáng 1 tên VC

Lịch sử Mít

liếm góc mép đầy máu của nó

Trên băng phải

trả tiền,

Một người

đàn ông và một người đàn bà

Trao đổi

những

cái hôn thèm khát

Xé nát

quần

áo của nhau

Gấu trố

mắt nhìn

Âm thanh

tắt

và căn phòng tối

Trừ màn

hình,

Đỏ như máu

Hồng như

Đông

Phương Hồng

Chế Lan Viên

thường nhắc câu này của Tế Hanh, không ghi xuất xứ :

Sang bờ tư

tưởng ta lìa ta,

Một tiếng gà

lên tiễn nguyệt tà.

Câu thơ diễn

tả tâm trạng người nghệ sĩ thời Pháp thuộc bước sang đời Cách mạng sau

1945, phải

“lột xác” để sáng tác, lìa bỏ con người trí thức tiểu tư sản, mong hòa

mình với

hiện thực và quần chúng. Câu thơ có hai mặt : tự nó, nó có giá trị thi

pháp,

tân kỳ, hàm súc và gợi cảm. Là câu thơ hay. Nhưng trong ý đồ của tác

giả, và

người trích dẫn, thì là một câu thơ hỏng, vì nó chứng minh ngược lại

dụng tâm

khởi thủy. Rõ ràng là câu thơ trí thức tiểu tư sản suy thoái.

Gậy ông đập

lưng ông. Đây là một vấn đề văn học lý thú.

Đặng Tiến tưởng

nhớ Tế Hanh

Tuyệt!

Thơ Mỗi Ngày

Underground Poems

Poems on the

Underground The Wider World

Two Poems Written at

Maple Bridge

Near Su-Chou

Maple

Bridge

Night Mooring

Moon set, a

crow caws,

frost fills

the sky

River,

maple, fishing-fires

cross my

troubled sleep.

Beyond the

walls of Su-chou

from Cold

Mountain temple

The midnight

bell sounds

reach my

boat.

written c.

AD 765

Chang Chi

Translated

by Gary Snyder

At MapLe

Bridge

Men are

mixing gravel and cement

At Maple

bridge,

Down an

alley by a tea-stall

From Cold

Mountain temple;

Where Chang

Chi heard the bell.

The stone

step moorage

Empty,

lapping water,

And the bell

sound has travelled

Far across

the sea.

written

AD 1984

Gary Snyder

Phong Kiều Dạ

Bạc

Nguyệt lạc ô

đề sương mãn thiên

Giang phong

ngư hỏa đối sầu miên

Cô Tô thành

ngoại Hàn San tự

Dạ bán chung

thanh đáo khách thuyền

Đỗ Thuyền

Đêm Ở Bến Phong Kiều

Trăng tà chiếc

quạ kêu sương

Lửa chài cây

bến sầu vương giấc hồ

Thuyền ai đậu

bến Cô Tô

Nửa đêm nghe

tiếng chuông chùa Hàn San

Tản Đà dịch

Poems on the

Underground Seasons

Wet Evening

in April

The birds

sang in the wet trees

And as I

listened to them it was a hundred years from now

And I was

dead and someone else was listening to them.

But I was

glad I had recorded for him

The

melancholy.

Patrick

Kavanagh

Chiều Ướt, Tháng Tư

Chim hót trên

cành ướt

Và Gấu nghe

chim hót, vào lúc, cách lúc này, một trăm năm.

Tất nhiên, Gấu

thì ngỏm rồi, và một ai đó đang nghe chim hót

May cho người

này là Gấu có ghi lại giùm cho anh ta hay chị ả

Nỗi buồn

Winter

Travels

who's typing

on the void

too many

stories

they're

twelve stones

hitting the

clockface

twelve swans

flying out

of winter

tongues in

the night

describe

gleams of light

blind bells

cry out for

someone absent

entering the

room

you see that

jester's

entered

winter

leaving

behind flame

Bei Dao

Translated

by David Hinton with Yanbing Chen

Du ngoạn Mùa

đông

người gõ lên

quãng không

rất nhiều

chuyện

chúng là mười

hai hòn đá

gõ lên mặt đồng

hồ

mười hai con

thiên nga

bay ra khỏi

mùa đông

những giọng

nói trong đêm

mô tả những tia

sáng

chuông mù

khóc ai đó vắng

mặt

đi vô phòng

bạn sẽ thấy,

của anh hề

đi vô mùa đông

để lại đằng

sau ngọn lửa

Bắc Đảo

Rilke

THE FIRST ELEGY

Who, if I cried out, would hear me

among the Angels?

Orders? and even if one of them pressed me

suddenly to his heart: I'd be consumed

in his more potent being. For beauty is nothing

but the beginning of terror, which we can still barely endure,

and while we stand in wonder it coolly disdains

to destroy us. Every Angel is terrifying.

Ai, nếu tôi kêu lớn, sẽ nghe, giữa

những Thiên Thần?

Những Thiên Sứ? và ngay cả nếu một vị

trong họ ôm chặt tôi vào tận tim:

Tôi sẽ bị đốt cháy trong hiện hữu dữ

dằn của

Người.

Bởi là vì, cái đẹp chẳng là gì, mà chỉ là khởi đầu của ghê rợn,

chúng ta

vẫn có thể chịu đựng, và trong khi chúng ta đứng ngẩn ngơ,

thì nó bèn

khinh khi

hủy diệt chúng ta.

Mọi Thiên Thần thì đều đáng sợ.

Rilke

For me, the

happy owner of the elegant slim book bought long ago, the Elegies

represented

just the beginning of a long road leading to a better acquaintance with

Rilke's

entire oeuvre. The fiery invocation that starts “The First Elegy” -

once again:

"Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the Angels' / Orders? And

even

if one of them pressed me / suddenly to his heart: 1'd be consumed / in

his

more potent being. For beauty is nothing / but the beginning of terror,

which

we can still barely endure" -had become for me a living proof that

poetry

hadn't lost its bewitching powers. At this early stage I didn't know

Czeslaw

Milosz's poetry; it was successfully banned by the Communist state from

the

schools, libraries, and bookstores-and from me. One of the first

contemporary

poets I read and tried to understand was Tadeusz Rozewicz, who then

lived in

the same city in which I grew up (Gliwice) and, at least

hypothetically, might

have witnessed the rapturous moment that followed my purchase of the

Duino

Elegies translated by Jastrun, might have seen a strangely immobile boy

standing in the middle of a side- walk, in the very center of the city,

in its

main street, at the hour of the local promenade when the sun was going

down and

the gray industrial city became crimson for fifteen minutes or so.

Rozewicz's

poems were born out of the ashes of the other war, World War II, and

were

themselves like a city of ashes. Rozewicz avoided metaphors in his

poetry,

considering any surplus of imagination an insult to the memory of the

last war

victims, a threat to the moral veracity of his poems; they were

supposed to be

quasi-reports from the great catastrophe. His early poems, written

before

Adorno uttered his famous dictum that after Auschwitz poetry's

competence was

limited-literally, he said, "It is barbaric to write poetry after

Auschwitz"-were already imbued with the spirit of limitation and

caution.

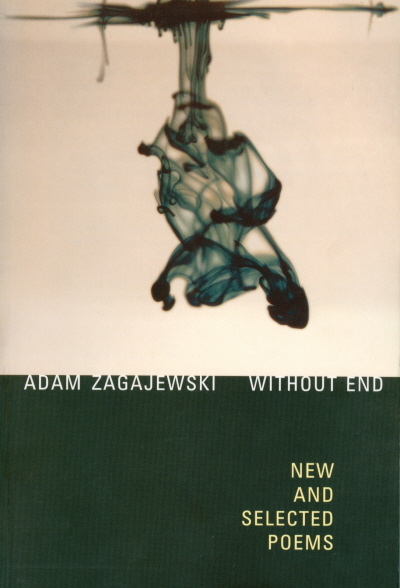

Adam Zagajewski: Introduction

Với tôi người sở hữu hạnh phúc, cuốn sách

thanh nhã, mỏng manh, mua từ lâu, “Bi Khúc” tượng trưng cho một khởi

đầu của

con đường dài đưa tới một quen biết tốt đẹp hơn, với toàn bộ tác phẩm

của Rilke.

“Bi Khúc thứ nhất” - một lần nữa ở đây: “Ai, nếu tôi la lớn - trở thành

một chứng

cớ hiển nhiên, sống động, thơ ca chẳng hề mất quyền uy khủng khiếp

của nó. Vào lúc đó, tôi chưa biết thơ của Czeslaw Milosz, bị “VC Ba

Lan”, thành

công trong việc tuyệt cấm, ở trường học, nhà sách, thư viện, - và tất

nhiên,

tuyệt cấm với tôi. Một trong những nhà thơ cùng thời đầu tiên mà tôi

đọc và cố

hiểu, là Tadeusz Rozewicz, cùng sống trong thành phố mà tôi sinh trưởng, (Gliwice), và, có

thể chứng kiến, thì cứ giả dụ như vậy, cái giây phút thần tiên liền

theo sau, khi

tôi mua được Duino Elegies, bản dịch của Jastrun - chứng kiến

hình ảnh một

đứa bé đứng chết sững trên hè đường, nơi con phố trung tâm thành phố,

vào giờ cư

dân của nó thường đi dạo chơi, khi mặt trời xuống thấp, và cái thành

phố kỹ nghệ

xám trở thành 1 bông hồng rực đỏ trong chừng 15 phút, cỡ đó – ui chao

cũng chẳng

khác gì giây phút thần tiên Gấu đọc cọp cuốn “Bếp Lửa”, khi nó được

nhà xb đem

ra bán xon trên lề đường Phạm Ngũ Lão, Sài Gòn – Thơ của Rozewicz như

sinh ra từ

tro than của một cuộc chiến khác, Đệ Nhị Chiến, và chính chúng, những

bài thơ, thì

như là một thành phố của tro than.

Rozewicz tránh sử

dụng ẩn dụ trong thơ của mình, coi bất cứ

thặng dư của tưởng tượng là 1 sỉ nhục hồi ức những nạn nhân của cuộc

chiến sau

chót, một đe dọa tính xác thực về mặt đạo đức của thơ ông: Chúng

được coi

như là những bản báo cáo, kéo, dứt, giựt ra từ cơn kinh hoàng, tai họa

lớn. Những

bài thơ đầu của ông, viết trước khi Adorno phang ra đòn chí tử, “thật

là ghê tởm,

man rợ khi còn làm thơ sau Lò Thiêu”, thì đã hàm ngụ trong chúng, câu

của

Adorno rồi.

Gấu đã viết như thế, về Bếp Lửa,

từ năm 1972

Giả như nó

không được đem bán xon, liệu có tái sinh?

Quá tí nữa,

giả như không có cuộc phần thư 1975, liệu văn học Miền Nam vưỡn còn, và

được cả

nước nâng niu, trân trọng như bây giờ?

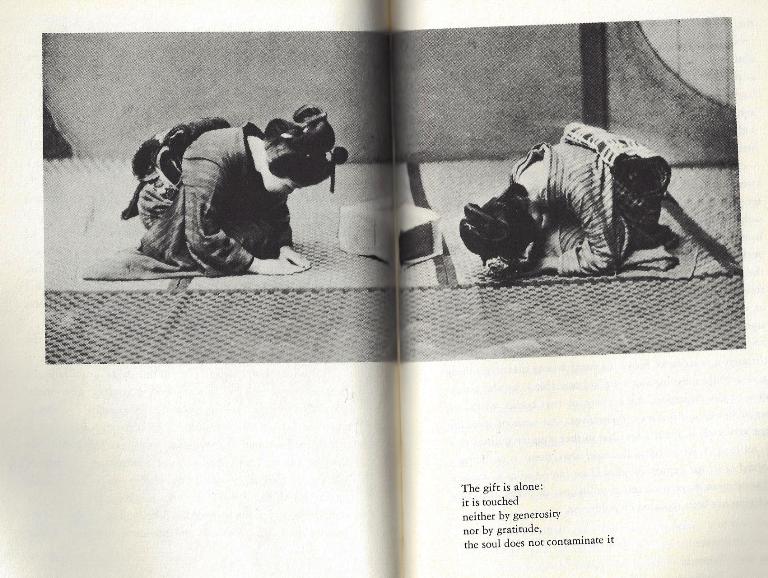

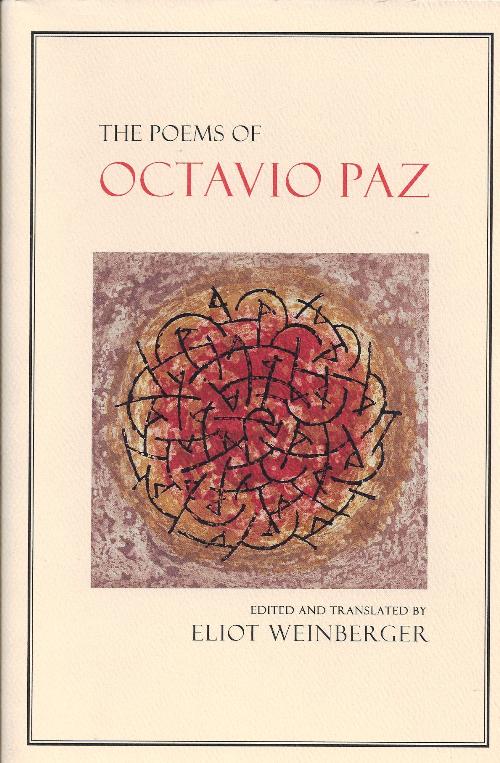

Thơ Mỗi Ngày

Octavio Paz

Mới tậu: Quà

SN của Cô Út. Câu chúc, “chỉ làm thơ, đừng thèm để ý đến thằng chó nào

nữa, lõ hay không

lõ… ”, của… K, SN năm ngoái, là ứng vào

năm nay!

Tks

again.

NQT

Real isn’t real

The

Poems of Octavio Paz

edited

and translated by Eliot Weinberger

Michael Wood

In 1950

André Breton published a prose poem by Octavio Paz in a surrealist

anthology.

He thought one line in the work was rather weak and asked Paz to remove

it. Paz

agreed about the line but was a little puzzled by the possibility of

such a

judgment on Breton’s part. He said: ‘What about automatic writing?’

Breton,

unperturbed, replied that the weak line was ‘a journalistic

intromission’. Your

true surrealist knows good automatisms from bad, high from low. We may

think,

as no doubt Paz did, that Breton was making an ordinary, and sound,

critical

call rather than a surrealist selection, but it’s interesting that he

could

make the call and still, however grandly or ironically, sustain the

lingo. The

lingo too has its virtues, and the question of who or what writes a

poem, which

agency creates which pieces, even if none of the players is exactly

automatic,

takes us a long way into Paz’s work, handsomely represented in this new

collection, from whose notes I have taken the above story.

Note:

Michael Wood điểm thơ Octavio Paz, do Eliot Weinberger dịch, trên

TLS. Bài

này thú, thứ hơn nữa, thơ trích dẫn, một số, được GCC trích dẫn, trên TV

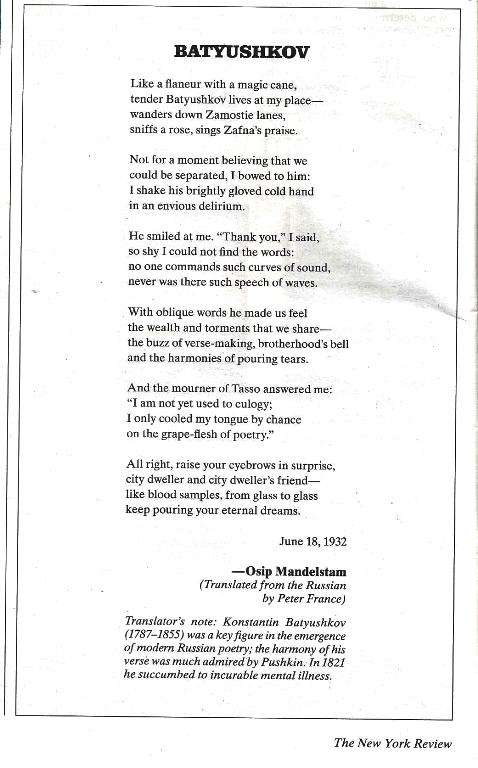

BATYUSHKOV

Like a

flaneur with a magic cane,

tender

Batyushkov lives at my place-

wanders down

Zamostie lanes,

sniffs a

rose, sings Zafna's praise.

Not for a

moment believing that we

could be

separated, I bowed to him:

I shake his

brightly gloved cold hand

in an

envious delirium.

He smiled at

me. "Thank you," I said,

so shy I

could not find the words:

no one

commands such curves of sound,

never was

there such speech of waves.

With oblique

words he made us feel

the wealth

and torments that we share-

the buzz of

verse-making, brotherhood's bell

and the

harmonies of pouring tears.

And the

mourner of Tasso answered me:

"I am

not yet used to eulogy;

I only

cooled my tongue by chance

on the

grape-flesh of poetry."

All right,

raise your eyebrows in surprise,

city dweller

and city dweller's friend-

like blood

samples, from glass to glass

keep pouring

your eternal dreams.

June 18,

1932

-Osip

Mandelstam

(Translated

from the Russian by Peter

France)

Translator's

note: Konstantin Batyushkov (1787-1855) was a key figure in the

emergence of

modern Russian poetry; the harmony of his verse was much admired by

Pushkin. In

1821 he succumbed to incurable mental illness.

NYRB, May 8

2014

Bác Nguyễn

Như gã

tản bộ với cây ba toong thần kỳ

Bác Nguyễn dễ mến sống ở chỗ Gấu - nhà Cậu Toàn, Phố Cổ -

Lang thang xuống Bờ Hồ, theo những Hàng Lụa, Hàng Buồm, Hàng Bạc

Ngửi ngửi một bông hồng, đi một đường thổi, “Hà Nội ta

đánh Mẽo giỏi”

Không

một khoảnh khắc nghi ngờ, Mẽo sẽ cút Ngụy sẽ nhào,

Cũng chẳng thể hồ nghi, một tên chăn trâu học lớp Một sẽ ngồi lên đầu

dân Mít

Hà, hà!

Gấu cúi

đầu chào sư phụ của mình

Gấu bắt tay, là cái bao tay lạnh như Hà Lội lạnh

Run run như thần tử diện long nhan

Bác

Nguyễn mỉm cười, Gấu đó ư, trẻ quá nhỉ!

[Thuổng MT khi gặp Thầy Kuốc lần

đầu]

Gấu bẽn lẽn không làm sao kiếm ra lời

Ngoài

Bác

Nguyễn ra,

Ai có thể điều

khiển được những lọn âm

Những đợn sóng

lời

Bằng những từ

nghiêng nghiêng

Như những giọt mưa chứa cơn gió nhẹ trong nó

Bác Nguyễn làm cho chúng ta cảm thấy

Sự giầu có và những khắc khoải mà chúng ta chia sẻ -

Thì thầm như thơ, bạn quí như oang vàng, khánh bạc

Vãi lệ hài hòa

Và người

than khóc Tasso trả lời Gấu:

“Ta không quen với cái trò thổi ống đu đủ; cái gì gì, đâu phải đời Mít

nào cũng

có được?

Ta chỉ uốn nhẹ cái lưỡi cho đầm cái ngọt ngào mới mẻ của thơ"

OK. Hãy dựng

cặp lông mi lên trong kinh ngạc

Cư dân Hà Lội và bạn của cư dân Hà Lội –

Như mẫu máu, từ ly này tới ly khác,

Hãy cứ vô tư tiếp tục rót những giấc mộng đời đời của mi

Gấu ơi là Gấu!

Tháng Sáu

18, 1932

Osip

Mandelstam

Ghi chú của

người dịch: Konstantin

Batyushkov là

nhà thơ chủ chốt của nền thi ca hiện đại Nga.

Pushkin rất mê

tính hài hòa trong thơ của ông. Mất năm 1821, vì 1 chứng nan y.

Poems on the

Underground

Thơ dán trên

Xe Điện Ngầm London

Exile and

Loss

Lưu vong và

Mất mát

My Voice

I come from a distant land

with a foreign knapsack on my back

with a silenced song on my lips

As I travelled down the

river of my life

I saw my voice

(like Jonah)

swallowed by a whale

And my very life lived in

my voice

Kabul,

December 1989

Partaw Naderi

Translated by Sarah

Maguire

and Yama Yari

Tiếng

nói của

tôi

Tôi tới từ một

miền đất xa

Cõng trên lưng

cái bị cói

Và trên lưỡi,

một bài hát câm

Trong lúc lần

mò theo con sông đời mình

Tôi thấy tiếng

nói của tôi

(như Jonah)

Bị một con cá

voi nuốt

Và cái đời rất

đời của tôi

Sống ở trong

tiếng nói của tôi

The Exiles

The many

ships that left our country

with white

wings for Canada.

They are

like handkerchiefs in our memories

and the

brine like tears

and in their

masts sailors singing

like birds

on branches.

That sea of

May running in such blue,

a moon at

night, a sun at daytime,

and the moon

like a yellow fruit,

like a plate

on a wall

to which

they raise their hands

like a

silver magnet

with

piercing rays

streaming

into the heart.

Iain

Crichton Smith

Translated

from the author's own Gaelic

Lưu vong

Rất nhiều tầu

rời xứ Mít

Cánh trắng

Nhắm tới Canada

Chúng giống

như những chiếc khăn tay

Trong hồi nhớ

của chúng tôi

Và biển mặn,

như nước mắt

Trên cột

buồm thuỷ thủ hát

Như chim trên

cành

Biển Tháng Năm

năm đó trải dài trong màu xanh

Trăng đêm,

ngày mặt trời

Và mặt trăng như trái cam màu vàng

Như cái dĩa

trên tường

Họ giơ tay về

chiếc dĩa bạc

Như có nam

châm

Với những đuờng

ray

Chảy tới tận

trong tim.

Rilke

Love in a mist

Yêu trong sương mù

Trên TV, độc giả đã từng

'chứng kiến' 'anh cu Gấu' chạy theo BHD nơi cổng trường Đại Học Khoa

Học Sài Gòn.

Chưa ghê bằng Apollinaire,

tác giả câu thơ mà GNV thuổng, "Ouvrez-moi cette porte où je frappe en

pleurant", còn là tác giả Mùa Thu Chết, và còn là tác giả của cái cú

chạy

theo em nữ quản gia, suốt con kênh nối liền Pháp và Anh, để năn nỉ.

Thua, và bèn làm bài thơ trên,

nguyên tác tiếng Tây, GNV sẽ lục tìm, và dịch sau… (1)

[Hình, TLS Oct 1, 2010]

NYRB May 8

2014

Poems on the Underground

Thơ dán

trên Xe Điện Ngầm London

Exile and Loss

My Voice

I come from

a distant land

with a

foreign knapsack on my back

with a

silenced song on my lips

As I

travelled down the river of my life

I saw my

voice

(like Jonah)

swallowed by

a whale

And my very

life lived in my voice

Kabul, December 1989

Partaw Naderi

Translated

by Sarah Maguire and Yama Yari

The Exiles

The many

ships that left our country

with white

wings for Canada.

They are

like handkerchiefs in our memories

and the

brine like tears

and in their

masts sailors singing

like birds

on branches.

That sea of

May running in such blue,

a moon at

night, a sun at daytime,

and the moon

like a yellow fruit,

like a plate

on a wall

to which

they raise their hands

like a

silver magnet

with

piercing rays

streaming

into the heart.

Poems on the

Underground Exile

and Loss

Iain

Crichton Smith

Translated

from the author's own Gaelic

Spring has

come again. The earth

is like a

child who knows poems by heart;

many, so

many! ... For the work

of such long

learning, she wins the prize.

Her teacher

was demanding. We'd grown fond

of the white

in the old man's beard.

N ow when we

ask her what the green and the blue are:

she can tell

us, she knows it, she knows!

Earth, lucky

earth, on holiday, play

with the

children now. We want to catch you,

happy earth.

And the luckiest will.

What her

teacher taught her! So many things,

and what's

imprinted in the roots and on the long

difficult

stems: she sings it, she sings!

Rilke

EXAMPLE

A gale

stripped all

the leaves from the trees last night

except for

one leaf

left

to sway solo

on a naked branch.

With this

example

Violence

demonstrates

that yes of

course-

it likes its

little joke from time to time.

Wislawa Symborska: Here

Thí dụ

Một trận gió

lạnh

Vặt trụ lá

cây, tối hôm qua

Trừ 1 cái

Trơ cu lơ

trên cành cây trần trụi

Với thí dụ

này

Lịch sử Mít

những ngày 1945

Bèn chứng tỏ

rằng thì là,

Thì tất

nhiên, đúng như thế rồi

Lâu lâu, thi

thoảng, ta cũng khoái chuyện tiếu lâm của ta!

Ui chao, VC

quả đã làm thịt ông bố, nhưng chừa ông con

Để sau này làm nhạc chào mừng ngày

30 Tháng Tư 1975:

Như có Bác Hồ trong ngày

vui đại thắng!

Bạn có thể

áp dụng bài thơ trên, cho rất nhiều trường hợp,

Với những kẻ

lịch sử tha chết để sau đó, làm 1 công việc, như trên!

Nào họ Trịnh

hầu đờn Hồ Tôn Hiến

Nào người

tri kỷ của ông hầu đờn Bắc Bộ Phủ.

Brodsky phán,

Virtue,

after all, is far from being synonymous with survival;

duplicity

is.

J. Brodsky:

"Collector's Item"

(Sống sót,

nói cho cùng, là do nhập nhằng, không phải bởi đạo hạnh).

Đành phải

cám ơn VC 1 phát!

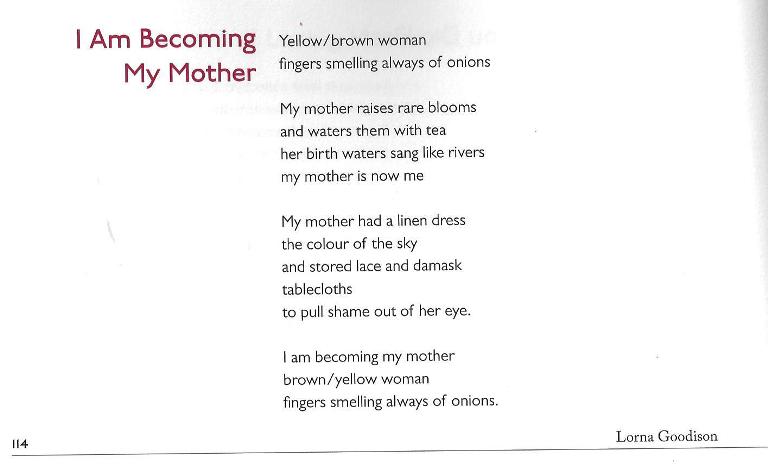

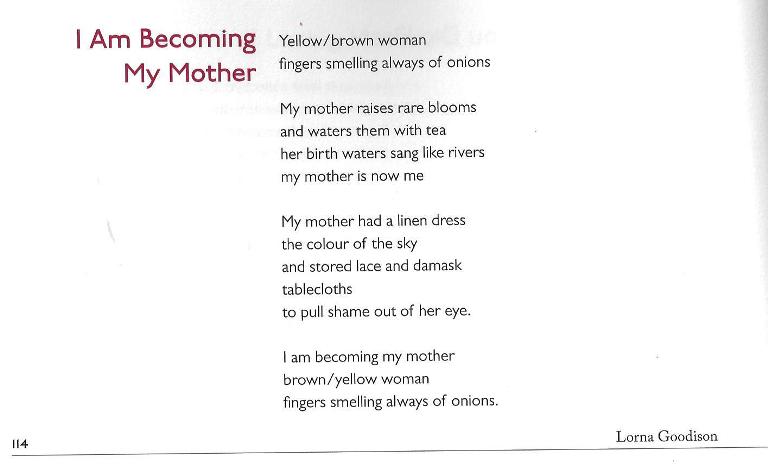

Happy Mother's Day

I Am

Becoming

My Mother

Yellow/brown

woman

fingers

smelling always of onions

My mother

raises rare blooms

and waters

them with tea

her birth

waters sang like rivers

my mother is

now me

My mother

had a linen dress

the colour

of the sky

and stored

lace and damask

tablecloths

to pull

shame out of her eye.

I am

becoming my mother

brown/yellow

woman

fingers

smelling always of onions.

Lorna

Goodison

Happy Mom’s

Day, from Jenny

Tôi đang trở

thành má tôi

Người đàn bà

/vàng/nâu

Mấy ngón tay

lúc nào cũng có mùi hành

Má tôi trồng

bông lạ

Tưới chúng bằng

nước trà

Ngày sinh của

bà nuớc reo như sông

Má tôi bây

giờ là tôi

Má tôi có

chiếc áo dài bằng lanh

Màu trời

Bà trữ

dây vải, lụa

tạp dề

Để lấy nỗi tủi

hổ khỏi mắt

Tôi trở thành

má tôi

người đàn bà/vàng/nâu

Ngón tay sặc

mùi hành

Bà cụ GCC @

Nghĩa Trang Quân Đội Gò Vấp, lần đưa xác thằng em trai từ Sóc Trăng về

mai táng;

@ 29/8D NBK Sài Gòn

Em tôi nằm

xuống với một viên đạn ở trong đầu. Mấy người lính kể lại, chuẩn uý

không kịp

đau đớn. Lời trối trăng nghe như gió thoảng lại: "Chắc tao chết mất..."

Trung đội vi hành tuần tra vòng đai phi trường Sóc Trăng. Khi nghe

tiếng súng, theo

phản xạ, em tôi chúi đầu về phía trước. Chiếc nón sắt quên không buộc

rớt xuống

và một viên đạn trong tràng AK từ bên sông bắn hú họa xuống mặt sông,

dội lên,

xớt qua vai rồi hết đà nằm luôn trong ót. Viên bác sĩ quân y nói với

tôi, ông

đã không lấy viên đạn ra vì sợ làm nát khuôn mặt. "Chuẩn ý Sĩ không kịp

ghi địa chỉ cấp báo. Chúng tôi phải nhờ Bưu Điện liên lạc với Sài-gòn.

Ngoài mấy

bức hình chụp lúc tẩm niệm, chuẩn uý không để lại gì cả. Quần áo, đồ

dùng cá

nhân, poncho... đều đi theo với chuẩn uý."

Có, có , chuẩn

uý Sĩ có để lại một bà mẹ đau khổ như bất cứ một bà mẹ nào có con trai

tử trận,

một người anh trai để mang xác em về nghĩa trang quân đội Gò Vấp mai

táng, một

đứa cháu còn nằm trong viện bảo sanh, người chú vô thăm lần đầu tiên và

cũng là

lần cuối cùng, như để tìm dấu vết thân thương, ruột thịt, trước đi vĩnh

viễn bỏ

đi...

Em tôi còn để

lại một thành phố Sài-gòn trong đó có tuổi trẻ của tôi, của em tôi,

thấp thoáng

đâu đó nơi đầu đường, cuối chợ Vườn Chuối, ngày nào ba mẹ con dắt díu

nhau rời

con tầu khổng lồ Marine Serpent, miệng còn dư vị hột vịt lộn, người dân

Sài-gòn

trên những ghe nhỏ bám quanh con tầu, chuyền lên boong, trong những

chiếc giỏ lủng

lẳng ở đầu những cây sào dài. Hai anh em mồ côi cha vừa mới mất Hà-nội,

ngơ

ngác nhìn thành phố qua những đống rác khổng lồ nơi đại lộ Hàm Nghi,

qua ánh điện

chói chang, sáng lòa trên mặt sông, trên những con tầu đậu nối đuôi

nhau suốt

hai bên bờ vùng Khánh Hội, và đổ dài trên những con lộ thẳng băng. Qua

những lần

đổi vai đòn gánh của bà mẹ, từ cháo gà, miến gà, tới cháo lòng, bún

riêu, bánh

cuốn... Qua ánh mắt thất vọng của Người. Bốn anh chị em, bây giờ chỉ

còn hai đứa,

vậy mà cũng không nuôi nổi. Cuối cùng cả ba mẹ con đành lạc lối giữa

những con

hẻm chi chít, chằng chịt vùng Bàn Cờ. Tôi đi làm bồi bàn cho tiệm chả

cá Thăng

Long, làm trợ giáo, cố gắng tiếp tục học. Em tôi điếu đóm, hầu hạ một

ông cử

già, bà con với anh Hoạt, chồng người chị họ. Anh Nguyễn Hoạt, tức Hiếu

Chân, bị

bắt chung với Doãn Quốc Sĩ, sau mất ở trong khám Chí Hòa, chính quyền

CS bắt phải

hủy xác thành tro, trước khi mang ra khỏi nhà tù.

Một Sài-gòn

trong có quán cà phê Thái Chi ở đầu đường Nguyễn Phi Khanh, góc Đa Kao.

Bà chủ

quán khó tính, chỉ bằng lòng với một dúm khách quen ngồi dai dẳng như

muốn dính

vào tuờng, với dăm ba tờ báo Paris Match, với mớ bàn ghế lùn tịt. Trên

tường

treo một chiếc dĩa tráng men, in hình một cậu bé mếu máo, tay ôm cặp,

với hàng

chữ Pháp ở bên dưới: "Đi học hả? Hôm qua đi rồi mà!"

Đó là nơi

em

tôi thường ngồi lỳ, trong khi chờ đợi Tình Yêu và Cái Chết. Cuối cùng

Thần Chết

lẹ tay hơn, không để cho nạn nhân có đủ thì giờ đọc nốt mấy trang Lục

Mạch Thần

Kiếm, tiểu thuyết chưởng đăng hàng kỳ trên nhật báo Sài-gòn, để biết

kết cục bi

thảm của mối tình Kiều Phong-A Tỷ, như một an ủi mang theo, thay cho

những mối

tình tưởng tượng với một cô Mai, cô Kim nào đó, như một nhắn nhủ với

bạn bè còn

sống: "Đừng yêu sớm quá, nếu nuốn chết trẻ." Chỉ có bà chủ quán là

không quên cậu khách quen. Ngày giỗ đầu của em tôi, bà cho người gửi

tới, vàng

hương, những lời chia buồn, và bộ bình trà "ngày xưa cậu Sĩ vẫn thường

dùng."

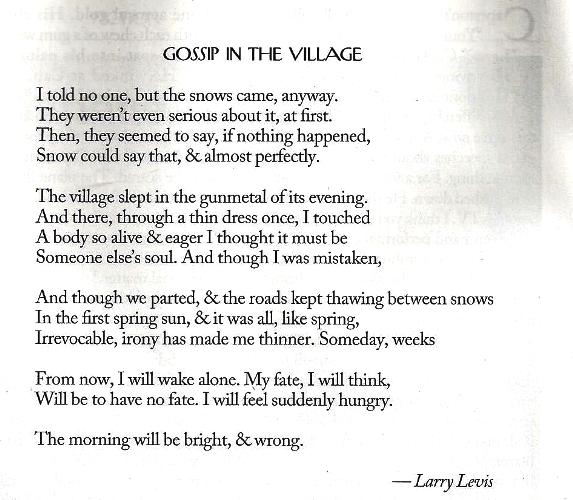

I Am

Becoming

My Mother

Yellow/brown

woman

fingers

smelling always of onions

My mother

raises rare blooms

and waters

them with tea

her birth

waters sang like rivers

my mother is

now me

My mother

had a linen dress

the colour

of the sky

and stored

lace and damask

tablecloths

to pull

shame out of her eye.

I am

becoming my mother

brown/yellow

woman

fingers

smelling always of onions.

Lorna

Goodison

Tôi đang trở

thành má tôi

Người đàn bà

/vàng/nâu

Mấy ngón tay

lúc nào cũng có mùi hành

Má tôi trồng

bông lạ

Tưới chúng bằng

nước trà

Ngày sinh của

bà nuớc reo như sông

Má tôi bây

giờ là tôi

Má tôi có

chiếc áo dài bằng lanh

Màu trời

Bà trữ

dây vải, lụa

tạp dề

Để lấy nỗi tủi

hổ khỏi mắt

Tôi trở thành

má tôi

người đàn

bà/vàng/nâu

Ngón tay

sặc

mùi hành

Handbag

My mother's

old leather handbag,

crowded with

letters she carried

all through

the war. The smell

of my

mother's handbag: mints

and lipstick

and Coty powder.

The look of

those letters, softened

and worn at

the edges, opened,

read, and

refolded so often.

Letters from

my father. Odour

of leather

and powder, which ever

since then

has meant womanliness,

and love,

and anguish, and war.

Poems on the

Underground Families

Ruth

Fainlight

Túi xách tay

Cũ, bằng da,

của má tôi

Chất chứa trong

đó là

Những lá thư

bà mang theo cùng với bà

Suốt cuộc

chiến

Mùi bạc hà,

mùi dầu cù là, mùi mồ hôi

Những lá thư,

góc quăn, mở gấp nhiều lần,

Chữ bạc dần

Thư của ba tôi

Túi da, kể từ

đó, nặng mùi nhất,

Là mùi đàn bà, tình yêu, thống khổ và sợ hãi.

Thơ Mỗi Ngày

CAFÉ DE

L’IMPRIMERIE

I wait for

you inside a glass beside

The long dim

window of the Cafe de l'Imprimerie.

I see you,

beautiful and wry

And not yet

here, and yet not here,

While this

late-summer evening never ends

And never

ends but is infinitesimally

Dimming on

the street beside Les Halles, where I

Can see you,

beautiful and wry as you draw near,

And I am

reassured you are not coming. Yes.

All night I

wait for you at the Cafe de l'Imprimerie.

Your absence

makes you beautiful and wry

And this

late-summer evening never ends,

Nor does the

beautiful intolerable

Music, where

the truth is cut

With

sentiment and surely fatal.

Come now. Do

not come. Come now. Do not,

And lead me

to a room where you undress,

A bare white

room at an untraceable address

Where we

will stay forever. Come now. Do not. Yes.

-Sean

O'Brien

The New

Yorker, May 12, 2014

Cà Phê

Factory

Gấu đợi Em ở

bên trong lớp kính

Bên cạnh ô cửa

tối mờ mờ ở Cà Phê Factory

Gấu thấy Em,

đẹp và nhăn nhó

Nhưng chưa, chưa

phải ở đây, chưa phải ở đây

Khi buổi chiều

hè muộn chẳng hề chấm dứt

Chẳng hề chấm

dứt, nhưng cứ li ti mãi ra

Đường phố bên

ngoài Little Sài Gòn mờ mờ tối

Nơi Gấu có

thể nhìn thấy Em, đẹp ơi là đẹp, đẹp và nhăn nhó, đẹp tới đâu nhăn nhó

tới đó -

chắc giống Tây Thi mỗi lần đau, nhăn mặt, là mỗi lần cực đẹp –

và Em tới gần

Và Gấu chắc

chắn Em đếch có tới. Đúng như thế.

Suốt đêm Gấu

đợi Em ở Cà Phê Factory, ở Little Sài Gòn

Cái sự vắng

mặt của Em thì đẹp và nhăn nhó, tuyệt vời làm sao

Và buổi chiều

hè muộn chẳng khi nào chấm dứt.

Cũng thế, là

cái thứ âm nhạc thần sầu không làm sao chịu nổi

Khi sự thực

bị chém 1 cú

Bằng tình cảm

và bi thương, như số phần nghiệt ngã.

Em cứ hẹn,

nhưng Em đừng tới nhé

Tới lúc này.

Đừng. Đừng.

Và dẫn Gấu tới căn phòng, nơi Em xỏa quần áo,

Một căn phòng

trần trụi, địa chỉ đếch làm sao truy ra được

Nơi chúng ta

sẽ ở đó suốt đời. Mai mãi.

Em cứ hẹn,

nhưng Em đừng tới nhé!

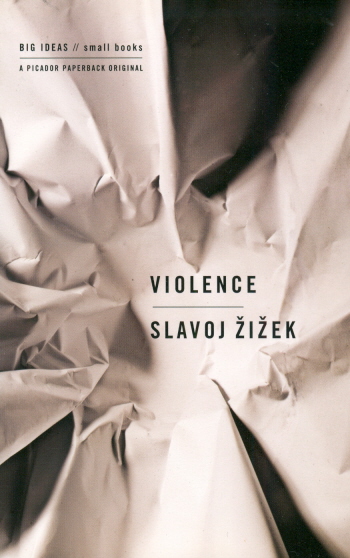

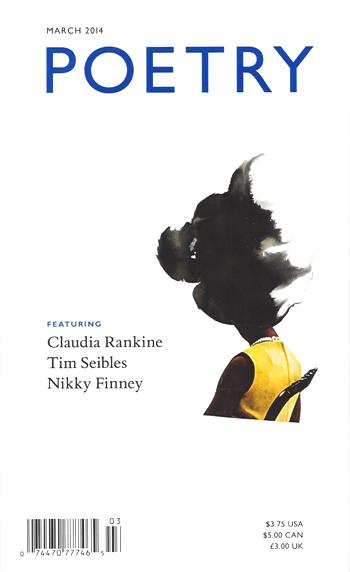

The Poetic

Torture-House of Language

Căn nhà tra

tấn thơ của ngôn ngữ

Cái dạng thức

sơ đẳng nhất của tra tấn ngôn ngữ được gọi là

thơ ca.

GCC đọc, nội câu trên, cộng thêm tên tác giả, là bèn xỉa 5 đồng ra, để

mua tờ

báo! Trên đường về đọc sơ sơ bài viết, “The Poetic-Torture-House of

Language” là

đã điếng hồn rồi, y như nghe tiếng gà gáy trưa của 1 nhà thơ Mít.

Zizeck trích 1 câu của Jeninek, Nobel văn chương, đọc 1

phát,

thấy như được chích 1 phát, như ngày nào còn ghiền:

Ngôn ngữ nên được đè ra tra tấn, để nói sự thực.

Language

should be tortured to tell the truth.

Quá cần cho

xứ Mít.

Xứ của Thơ!

Merde!

What if, however, humans

exceed animals in their capacity for violence precisely because they speak?

Liệu con người hung bạo hơn

loài vật, là do chúng... nói?

Không chỉ nói, mà khốn kiếp hơn, làm thơ?

Tiếng tăm của

Plato xem chừng bị tổn thương vì câu phán của ông - thi sĩ nên tống ra

khỏi

thành phố: Thay vì vậy, nếu nhìn từ kinh nghiệm hậu chiến Nam Tư, nơi

những cuộc

thành trừng chủng tộc được sửa soạn, từ những giấc mộng nguy hiểm của

những tên

thi sĩ.

Đúng như thế, Slobodan Milosevic “thao tác, giật giây” những đam mê,

tình cảm, yêu nước là yêu chủ nghĩa Xạo Hết Chỗ Nói – nhưng chính những

nhà thơ

đã đem đến cho ông ta cái chất liệu, và cái chất liệu này tự nó thêm vô

trò giật

giây, nhào nặn, thao tác. Họ - những nhà thơ chân thực - không phải

những nhà chính trị bị tha hoá, đồi bại – là nguồn cơn của tất cả, kể

từ khi -

nếu chúng ta trở lại với thế kỷ 17, đầu thế kỷ 18, họ bắt đầu gieo mầm

thứ chủ nghĩa quốc gia hiếu chiến không chỉ ở Serbia, mà còn ở những xứ

cộng

hòa cựu Nam Tư.

Thay vì mặc cảm binh bị,

kỹ nghệ, chúng ta, ở thời kỳ hậu Nam

Tư, có mặc cảm binh bị thơ, the

poetic-military complex, nhập thân, hóa thân

vào cặp song sinh, Radovan Karadzic và Ratko Mladic. Karadzic không chỉ

là 1

nhà lãnh đạo quân sự, chính trị mà còn là 1 nhà thơ. Thơ của ông ta,

chớ nên

coi thường, vứt sọt rác, coi như thơ của những thi sĩ Mít đầy rẫy trên

net bi

giờ - mà cần 1 sự đọc gần, bởi là vì nó cung cấp cho chúng ta cái chìa

khóa

để hiểu, làm cỏ chủng tộc vận

hành ra làm sao.

Nhìn lại chủ

nghĩa toàn trị

Nhìn lại chủ

nghĩa toàn trị

"Tại

sao bần cố

nông trong thời đẫm thơ?"

[What are the destitute (proletarians) for in

a

poetic time?]

The Paris

Review

From the

Archive

1977

Marguerite

Young

READING THE

NOTEBOOK OF

ANNA

KAMIENSKA

Reading her,

I realized how rich she was and myself, how poor

Rich in love

and suffering, in crying and dreams and prayer.

She lived

among her own people who were not very happy but

supported

each other,

And were

bound by a pact between the dead and the living renewed

at the

graves.

She was

gladdened by herbs, wild roses, pines, potato fields

nd the

scents of the soil, familiar since childhood.

She was not

an eminent poet. But that was just:

A good

person will not learn the wiles of art.

Đọc Sổ Ghi của

Anna Kamienska (1)

Đọc bà, tôi

nhận ra bà giầu biết bao, còn tôi, nghèo làm sao.