|

From

Russia With Love

On Joseph Brodsky WHEN THE LAST things are taken

out of a house, a strange, resonant echo settles in, your voice bounces

off the walls and returns to you. There's the din of loneliness, a draft

of emptiness, a loss of orientation, and a nauseating sense of freedom:

everything's allowed and nothing matters, there's no response other than

the weakly rhymed tap of your own footsteps. This is how Russian literature

feels now: just four years short of millennium's end, it has lost the greatest

poet of the second half of the twentieth century and can expect no other.

Joseph Brodsky has left us, and our house is empty. He left Russia itself

over two decades ago, became an American citizen, loved America, wrote essays

and poems in English. But Russia is a tenacious country: try as you may

to break free, she will hold you to the last. "Who appointed you a poet?"

they screamed at him. Neither country nor churchyard will I choose he promised in a youthful poem.

In the dark I won't find your deep blue facade I think that the reason

he didn't want to return to Russia even for a day was so that this incautious

prophecy would not come to be. A student of-among others-Akhmatova and

Tsvetaeva, he knew their poetic superstitiousness, knew the conversation

they had during their one and only meeting. "How could you write that? Don't

you know that a poet's words always come true?" one of them reproached.

''And how could you write that?" the other was amazed. And what they foretold

did indeed come to pass. "Joseph, will you come to Russia?" Did he want to go home?

I think that at the beginning, at least, he wanted to very much, but he

couldn't. He was afraid of the past, of memories, reminders, unearthed

graves, was afraid of his weakness, afraid of destroying what he had done

with his past in his poetry, afraid of looking back at the past-like Orpheus

looked back at Eurydice-and losing it forever. He couldn't fail to understand

that his true reader was there, he knew that he was a Russian poet, although

he convinced himself -and himself alone-that he was an English-language

poet. He has a poem about a hawk ("A Hawk's Cry in Autumn") in the hills

of Massachusetts who flies so high that the rush of rising air won't let

him descend back to earth, and the hawk perishes there, at those heights,

where there are neither birds nor people nor any air to breathe. He had an extraordinary tenderness

for all his Petersburg friends, generously extolling their virtues, some

of which they did not possess. When it came to human loyalty, you couldn't

trust his assessments-everyone was a genius, a Mozart, one of the best poets

of the twentieth century. Quite in keeping with the Russian tradition, for

him a human bond was higher than Justice, and love higher than truth. Young

writers and poets from Russia inundated him with their manuscripts-whenever

I would leave Moscow for the United States my poetic acquaintances would

bring their collections and stick them in my suitcase: "It isn't very heavy.

The main thing is, show it to Brodsky. Just ask him to read it. I don't need

anything else- just let him read it!" And he read and remembered, and told

people that [he poems were good, and gave interviews praising the fortunate,

and they kept sending their publications. And their heads turned; some said

things like: "Really, there are two genuine poets in Russia: Brodsky and

myself." He created the false impression of a kind of old patriarch - but

if only a certain young writer whom I won't name could have heard how Brodsky

groaned and moaned after obediently reading a story whose plot was built

around delight in moral sordidness. "Well, all right, I realize that after

this one can continue writing. But how can he go on living?" And two girls-sisters from unlived

years And indeed he left two girls

behind-his wife and daughter. "Do you know, Joseph, if you

don't want to come back a lot of fanfare, no white horses and excited crowds,

why you just go to Petersburg incognito?" He looked through me and murmured:

"Wonderful. Wonderful." Bài viết này, của Tolstaya, GCC đọc, khi nó được in trong 1 số báo - hình như tờ NYRB - như 1 bài tưởng niệm Joseph Brodsky, khi ông vừa mới mất, và có chôm 1 khúc, để tưởng niệm (cũng Joseph), nhưng mà là Huỳnh Văn. Sau đó, đưa tờ tờ báo cho Nguyễn Tiến Văn. Anh đọc, và sau đó, than, ông đọc, và bỏ 1 khúc quá quan trọng…. Ý của anh, là, Gấu ăn hết thịt, chỉ dành cho độc giả cục xương! Không phải như vậy. Bài viết của Gấu, về Joseph Huỳnh Văn, chỉ mượn có 1 khúc, trong bài viết của Tolstaya. Còn 1 khúc nữa, cũng trong bài viết, là Gấu dím lại, để dành cho bài viết về Đỗ Long Vân. DLV và Joseph HV là bạn ở ngoài đời. Cái hình ảnh nói lên tập tục của người Nga, khi người thân mất, họ phủ kín những tấm gương... hình ảnh này dành cho Đỗ Long Vân quá tuyệt vời. Khi đọc bài viết, là Gấu đã giữ lại hình ảnh đó, là vậy. Trong From Russia With Love, tác giả cũng nhắc tới bài viết này, và cho rằng quá trễ rồi, dù rằng "wonderful": Nhà của Brodsky, là NY, không còn là Nga nữa. NY: Home

"Do you know, Joseph, if you

don't want to come back with a lot of fanfare, no white horses and excited

crowds, why don't you just go to Petersburg incognito?" [. . .] Here I

was talking, joking, and suddenly I noticed that he wasn't laughing [.

.. ] He sat quietly, and I felt awkward, as if I were barging in where I

wasn't invited. To dispel the feeling, I said in a pathetically hearty voice:

"It's a wonderful idea, isn't it?" He looked through me and murmured: "Wonderful.

. . Wonderful ... "

Thứ

Sáu, ngày 8 tháng 3 năm 1996, vào lúc 5 giờ chiều, buổi tưởng niệm

thi sĩ Joseph Brodsky (tháng Năm 24, 1940 - tháng Giêng 28, 1996),

Nobel văn chương 1987, tại nhà thờ St. John the Divine, New York, có

lẽ đã đúng như ý nguyện của ông. Thay vì cuộc sống vị kỷ, những người

bạn của ông đã nhắc nhở nhau về những chu toàn, the achievements, ngôn

ngữ - the language - của người quá cố: [Tĩnh vật, trong Phần Lời, Part of Speech] (Chết sẽ

tới và sẽ thấy một xác thân

Ông sang Mỹ, nhập tịch Mỹ, yêu nước Mỹ, làm thơ, viết khảo luận bằng tiếng Anh. Nhưng nước Nga là một xứ đáo để (Chắc đáo để cũng chẳng thua gì quê hương của mi...): Anh càng rẫy ra, nó càng bám chặt lấy anh cho tới hơi thở chót. -Bao giờ ông về?. -Có thể, tôi không biết. Có lẽ. Nhưng năm nay thì không. Tôi nên về. Tôi sẽ không về. Đâu có ai cần tôi ở đó. -Đừng nói bậy, họ sẽ không để ông một mình đâu. Họ sẽ công kênh ông trên đường phố... tới tận Moscow... Tới Petersburg... Ông sẽ cưỡi ngựa trắng, nếu ông muốn. -Đó là điều khiến tôi không muốn về. Tôi đâu cần ai ở đó.

* Theo Tatyana Tolstaya, nhà văn nữ người Nga hiện đang giảng dạy môn văn chương Nga và viết văn, creative writing, tại Skidmore College, thoạt đầu, ông rất muốn về, ít nhất cũng như vậy. Ông đã từng nổi giận về những lời trách cứ. "Họ không cho phép tôi về dự đám tang ông già. Bà già chết không có tôi ở bên. Tôi hỏi xin nhưng họ từ chối". Cho dù vậy, lý do, theo Tolstaya, là ông không thể về. Ông sợ quá khứ, kỷ niệm, hồi nhớ, những ngôi mộ bị đào bới. Sợ sự yếu đuối của ông. Sợ hủy diệt những gì ông đã làm được, với quá khứ của ông, trong thi ca của ông. Ông sợ mất nó như Orpheus đã từng vĩnh viễn mất Eurydice, khi ngoái cổ nhìn lại.

Mỗi lần từ Nga trở về, hành trang của Tolstaya chật cứng những bản thảo của những thi sĩ, văn sĩ trẻ. "Cũng không nặng gì lắm đâu. Xin trao tận tay thi sĩ. Nói ông ta đọc. Tôi chỉ cần ông ta đọc". Ông đã đọc, đã nhớ và đã nói, thơ của họ tốt... Và ca ngợi điều may mắn. Và những nhà thơ trẻ của chúng ta đã hất hất cái đầu, ra vẻ: "Thực sự, chỉ có hai nhà thơ thứ thiệt tại Nga, Brodsky và chính tôi". Ông tạo nên một cảm tưởng giả, ông là một thứ ‘Bố già văn nghệ’. Nhưng chỉ một số ít ỏi thi sĩ trẻ đã từng nghe ông rên rỉ: Sau cái thứ này, tôi biết anh ta vẫn tiếp tục viết, nhưng làm sao anh ta tiếp tục sống!

Ông không tới với nước Nga, nhưng nước Nga đến với ông. Nhà thơ Nga kỳ cục không muốn bám rễ vào đất Nga. Kỳ cục thật, bởi vì đã từ lâu, thế hệ lạc loài được Hemingway mô tả trong Mặt Trời Vẫn Mọc, The Sun Also Rises vẫn luôn luôn là một ám ảnh đối với những kẻ bị bứng ra khỏi đất. Nếu không trở nên điên điên, khùng khùng thì cũng bị thương tật, (bất lực như nhân vật chính trong Mặt Trời Vẫn Mọc), bị bệnh kín (La Mort dans l'Âme: Chết trong Tâm hồn), và chỉ là những kẻ thất bại. Đám Cộng sản trong nước chẳng vẫn thường dè bỉu một nền văn chương hải ngoại? Nhưng Brodsky là một ngoại lệ. Nước Nga đã đến với ông. Thơ ông được xuất bản, đăng tải trên hầu hết các báo chí tại Nga. Trong một cuộc thăm dò dư luận tại đường phố Moscow: "Ông có mong ước, hy vọng gì liên quan đến cuộc bầu cử?", một người thợ mộc đã trả lời: "Tôi chỉ mong sống một cuộc đời riêng tư. Như Joseph Brodsky".

*

-Ai chỉ định anh là thi sĩ? Đám Cộng sản Liên-xô đã từng hét vào mặt ông như vậy tại phiên tòa. Họ chẳng thèm để ý đến những tài liệu, giấy tờ chứng minh từng đồng kopech ông có được qua việc sáng tác, dịch thuật thi ca. -Tôi nghĩ có lẽ ông Trời. Được thôi. Và tù đầy, lưu vong.

Neither country

nor churchyard will I choose (Xứ sở làm

chi, phần mộ làm gì (Trong đêm

tối thấy đâu, gương mặt em thăm thẳm xanh, xưa

Những lằn đan chéo, the crossed lines, hay rõ hơn, bờ ranh Nga Mỹ phân biệt số phận hai mặt của một kẻ ăn đậu ở nhờ. * -Này thi sĩ, nếu ông muốn về không ngựa trắng mà cũng chẳng cần đám đông reo hò, ngưỡng mộ, tại sao ông không về theo kiểu giấu mặt? -Giấu mặt? Đột nhiên thi sĩ hết tức giận, và cũng bỏ lối nói chuyện khôi hài. Ông chăm chú nghe. -Thì cứ dán lên một bộ râu, một hàng ria mép, đại khái như vậy. Cần nhất, đừng nói cho bất cứ một người nào. Và rồi ông sẽ dạo chơi giữa phố, giữa người, thảnh thơi và chẳng ai nhận ra ông. Nếu thích thú, ông có thể gọi điện thoại cho một người bạn từ một trạm công cộng, như thể ông từ Mỹ gọi về. Hoặc gõ cửa nhà bạn: "Tớ đây này, nhớ cậu quá!" Giấu mặt, tuyệt vời thật!

==oOo==

Joseph Huỳnh Văn là một thi sĩ. Chúng tôi quen nhau những ngày làm Tập san Văn chương. Có Nguyễn Tử Lộc, đã chết vì bệnh tại Sài-gòn ít lâu sau 75. Phạm Hoán, Phạm Kiều Tùng, Nguyễn Đạt, Nguyễn Tường Giang... Huỳnh Văn là Thư ký Tòa soạn. Không có Phạm Kiều Tùng, tập san không có một ấn loát tuyệt hảo. Nguyễn Đông Ngạc khi còn sống vẫn tự hào về cuốn Những Truyện Ngắn Hay Nhất Của Quê Hương Chúng Ta (Hai Mươi Năm Văn Học Miền Nam) do anh xuất bản, Phạm Kiều Tùng, Phạm Hoán lo in ấn, trình bày. Bạn lấy đầu một cây kim chấm một đầu trang. Dấu chấm đó sẽ xuyên suốt mọi đầu trang thường của cuốn sách. Không có Nguyễn Tường Giang thì không đào đâu ra tiền và mối thiện cảm, độc giả, thân hữu quảng cáo dành cho tập san. Những bài khảo luận của Nguyễn Tử Lộc và sở học của anh chiết ra từ những dòng thác ngầm của nhân loại - dòng văn chương Anglo-Saxon - làm ngỡ ngàng đám chúng tôi, những đứa chỉ mê đọc sách Tây, một căn bệnh ấu trĩ nhằm tỏ sự khó chịu vì sự có mặt của những quân nhân Hoa-kỳ tại Miền Nam.

Huỳnh Văn với lối nói mi mi tau tau là chất keo mà một người Thư ký Tòa soạn cần để kết hợp anh em. Bây giờ nghĩ lại chính thơ anh mới là tinh thần Tập San Văn Chương. Đó là nơi xuất hiện Cầm Dương Xanh , những bài thơ đầu mà có lẽ cũng là cuối của anh. Bởi vì sau đó, anh không đăng thơ nữa, tuy chắc chắn vẫn làm thơ, hoặc tìm thấy thơ trên những vân gỗ, khi anh làm nghề thợ mộc, những ngày sau 75, thay cho nghề bán cháo phổi, những ngày trước đó.

"Mỗi thời đại, con người tự chọn mình khi đứng trước tha nhân, tình yêu, và cái chết." (Sartre, Situations). Trong thơ Nguyễn Bắc Sơn, tha nhân là những người ở bên kia bờ địa ngục, và chiến tranh chỉ là một cuộc rong chơi. Nguyễn Đức Sơn tìm thấy Cửa Thiền ở một nơi khác, ở Đêm Nguyệt Động chẳng hạn. Thanh Tâm Tuyền muốn trút cơn đau của thơ vào thiên nhiên: Mùa này gió biển thổi điên lên lục địa...

Còn Huỳnh Văn, có vẻ như anh chẳng màng chi đến cuộc chiến, hoặc cuộc chiến tránh né anh. Tinh thần mắt bão của thiên nhiên thời tiết, hay tinh thần mắt nghe, l'oeil qui écoute, của Maurice Blanchot? Ôi khúc Cầm

Dương sầu quí phái

Thơ anh là một ngạc nhiên, hồi đó. Và tôi vẫn còn ngạc nhiên, bây giờ, khi được tin anh mất. (1) Khi liên tưởng đến câu thơ của một người bạn: Hồn Đông Phương thất lạc buồn Phương Tây (thơ TKA) Vọng Mỹ Nhân hề, thiên nhất phương (Có thể

mượn ý niệm "con người hoàn toàn" (l'homme total), hay giấc đại mộng

của Marx, làm nhịp cầu liên tưởng, để thấy rằng những Mỹ Nhân, Đấng

Quân Vương, Thánh Chúa... trong thi ca Đông Phương không hẳn chỉ là

những giấc mộng điên cuồng của thi sĩ): Vọng Mỹ nhân hề, vị lai Đọc trong nước, có vẻ như Thơ đang trên đường đi tìm một Mỹ nhân cho cả ngôn ngữ lẫn cuộc đời. Và Buồn

Phương Tây, có thể từ ý thơ Quang Dũng: Khuya nức

nở những cõi lòng không ngủ

(1) Joseph

Huỳnh Văn Hiến mất ngày 20/2/1995 tại Sài Gòn. Vô Kỵ Giữa Chúng Ta

Đỗ Long Vân, tác giả Truyện Kiều ABC, Vô Kỵ Giữa Chúng Ta,

Nguồn Nước Ẩn Trong Thơ Hồ Xuân Hương... đã mất tháng Tám năm vừa qua (1997),

tại quê nhà. Người biết chỉ được tin, qua mấy dòng nhắn tin, trong mục

thư tín, trên tạp chí Văn Học, số tháng Ba, 1998.

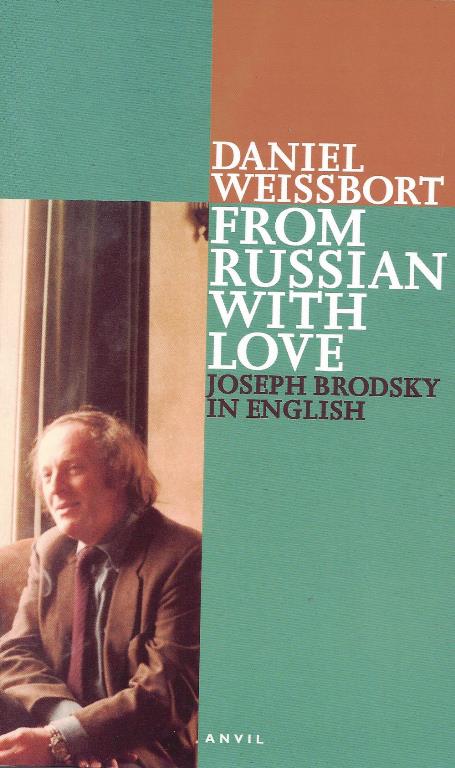

Reading in Iowa City, Iowa Đọc thơ ở Iowa City SOME YEARS ago, Joseph came

to Iowa City, the University of Iowa where I directed the Translation Workshop,

to give a reading; I was to read the English translation. At the end, he

was asked a number of (mostly loaded) questions, including one (alluded to

earlier) about Solzhenitsyn. "And the legend which had been built around

him?" His answer managed to be both artfully diplomatic and truthful: "Well,

let's put it this way. I'm awfully proud that I'm writing in the same language

as he does." (Note, again, how he expresses this sentiment in terms of language.)

He continued, in his eccentrically pedagogical manner, forceful, even acerbic,

but at the same time disarming, without any personal animus: "As for legend

... you shouldn't worry or care about legend, you should read the work. And

what kind of legend? He has his biography ... and he has his words. "For

Joseph a writer's words were his biography, literally! On another visit to Iowa,

in 1987, Joseph flew in at around noon and at once asked me what I was doing

that day. I told him that I was scheduled to talk to an obligatory comparative

literature class about translation. "Let's do it together", he said. Consequently

I entered the classroom, with its small contingent of graduate students,

accompanied by that year's Nobel Laureate. Joseph indicated that he

would just listen, but soon he was engaging me in a dialogue, except it was

more monologue than dialogue. Finally, he was directly answering questions

put to him by the energized students. I wish I could remember what was said,

but, alas, even the gist of it escapes me now. I did not debate with him,

even though our views on the translation of verse form differed radically.

Instead, I believe that I nudged him a little, trying - not very sincerely

or hopefully, though perhaps in a spirit of hospitality and camaraderie -

to find common ground. After the class, I walked back with him to his hotel,

as he said he wanted to rest before the reading. On the way, the conversation,

at my instigation, turned to Zbigniew Herbert, the Polish poet so greatly

admired by Milosz and, I presumed, by Brodsky, and indeed translated by the

former into English and by the latter into Russian. Arguably, Herbert was

the preeminent European poet of his remarkable generation. He was living in

Paris and apparently was not in good health. "Why hasn't Zbigniew been awarded

the Nobel Prize? Can't something be done about it", I blurted out - recklessly,

tactlessly, presumptuously. The subtext was: Surely you, Joseph Brodsky,

could use your influence, etc. Joseph came to a standstill: "Of course, he

should have it. But nobody knows how that happens. It's a kind of accident."

He locked eyes with me. "You're looking at an accident right now!" This was

not false modesty on his part, but doubtless he was being more than a little

disingenuous. Nevertheless, I believe that, at a certain level, he did think

of his laureateship as a kind of accident. Paradoxically, while he aimed

as high as may be, he was not in the business of rivalling or challenging

the great. They remained, in a sense, beyond him, this perception of destiny

and of a hierarchy surely being among his saving graces. In a far deeper sense, though,

they were not in the least beyond him, nor was he uncompetitive, but it did

not (nor could it) suit his public or even private persona to display this. Brodsky certainly considered

himself to be - and it is increasingly clear that he was - in the grand line

that included Anna Akhmatova, Boris Pasternak, Osip Mandelstam and Marina

Tsvetayeva. Even I sensed this, despite my ambivalence about his poetry.

Indeed, the continuity embodied in his work accounts, in part, for my uncertainty:

I have tended to rebel against grand traditions. But perhaps this is to exaggerate.

At times I hear the music, at other times the man, even if, as a rule, I

do not hear them both together ... But take, for instance, this (the last

three stanzas of "Nature Morte" in George Kline's splendid version in the

Penguin Selected Poems): Mary now speaks to Christ: How can I close my eyes, Christ speaks to her in turn: It is true that, as I listen

to or read the English, I hear the Russian too, in Joseph's rendition. I

even see Joseph, his hands straining the pockets of his jacket, his jaw jutting,

as though his eye had just been caught by something and he were staring at

it, scrutinizing it, while continuing to mouth the poem, almost absent- mindedly,

that is, while the poem continues to be mouthed by him. His voice rises symphonically:

Syn ili Bog (Son or God), "God" already (oddly?)

on the turn towards an abrupt descent; and then the pause and a resonant

drop, a full octave: Ya tvoi (I am thine). And the poet,

with an almost embarrassed or reluctant nod, and a quick, pained smile, departs

his poem. Note: Bài này cũng cực thú.

Bị khán giả chất vấn, mi so sao với Solz, Brodsky bèn trả lời, tớ có cái

hãnh diện là viết bằng cùng thứ tiếng với ông ta: "And the legend which had been

built around him?" His answer managed to be both artfully diplomatic and

truthful: "Well, let's put it this way. I'm awfully proud that I'm writing

in the same language as he does." (Note, again, how he expresses this sentiment

in terms of language.) Chỉ có hai nhà thơ sống "sự thực

tuyệt đối" của thời chúng ta, bằng cuộc đời “đơn” của họ, là Brodsky và TTT! Son of Man and Son of God Tuesday, July 29, 2014 4:11

PM Thưa ông Gấu, Nguyên tác: Christ speaks to her in turn: Theo tôi, nên dịch như sau: Christ bèn trả lời: Best regards, DHQ Phúc đáp: Note: Không làm sao kiếm ra khúc dịch trật nữa! Son of Man and Son of God (2) Today at 12:02 PM Dear ông Gấu Cháu xin phép giúp ông tìm lại bản

dịch "trật" http://www.tanvien.net/new_daily_poetry/14.html Mary nói với Christ: Mary now speaks to Christ: Christ bèn trả lời: Christ speaks to her in turn: Best regards, Tks Như vậy là GCC không dịch được

từ “thine”, và không hiểu, từ "woman", trong câu thơ. … Anh khoe khong? V/v Đi tu tới bến. Bác Tru theo dao nao vậy? Toi theo dao tho ong baDen gia, doc Weil, thi lai tiec. Gia ma tre theo dao Ky To, chac là thành quả nhiều hơn, khi doc Weil. NY: Nhà

Khi chàng già đi, có tuổi mãi ra – những năm sau cùng, chàng già hơi bị nhanh, như muốn

bắt kịp khúc chót, hoặc tóm lấy nó, vượt quá nó, nếu có thể, hà, hà… - một

thứ âu lo về đời, nhìn lại đời mình “cái con mẹ gì đó”, thay thế cái vẻ chua

chát trước đó, nhưng ngay cả như thế, thì thế giới vưỡn là 1 nơi chốn tuyệt

vời. Sức sáng tạo của Joseph vưỡn chưa bỏ chạy chàng!

From Russia With Love Tiếng Nga dịch được không? Is Russian Translatable? Theo Milosz, đếch dịch được!

Czeslaw Milosz, whom Joseph regarded as one of the preeminent poets of our time, re-iterated his belief that Russian poetry was "hardly translatable because of its particular features - strongly rhymed singsong verses among them". He added: "Modern Polish poetry does a little better because, in contrast to Russian, the Polish language benefits from abandoning both meter and rhyme, so that equivalents in English can more easily be found." He also believed, however, that the situation had improved somewhat, as a result of the increasing collaboration between poets in English and poets in the source language. The review in question is of a collaborative translation by Stanislaw Baranczak (Polish poet, essayist and Shakespeare translator, also the translator of Brodsky into Polish) and Seamus Heaney, the 1995 Nobel Laureate. Milosz mà Brodsky coi như một

trong những nhà thơ uyên bác nhất của thời của chúng ta, nhắc lại cái niềm

tin của ông, là thơ Nga thật khó dịch, vì những câu thơ của chúng thì chẳng

khác chi những lời ca trầm bổng giữa chúng mí nhau [tạm dịch cái ý “strongly

rhymed singsongs verses among them”]. Thơ Ba Lan hiện đại dễ dịch hơn, vì

ngược với thơ Nga, ngôn ngữ Ba Lan hưởng lợi nhờ cái cú, từ bỏ cả “meter”

lẫn “rhyme”, thành ra dễ có từ tương đương trong tiếng Anh. Cái tôi phóng chiếu

"Nobody in a raincoat": "Chẳng là ai trong cái áo mưa" Note: Bài viết này quả là hết xẩy con cào cào! Chúng ta đã biết Brodsky ra tòa VC Liên Xô, và trả lời, khi chúng hỏi, Ai cho phép mi là thi sĩ? Bài này thú vị hơn nhiều: Chàng, qua Tây Phương, lần đầu đăng đàn phán về thơ, giữa cử tọa Tây Phương! Tin Văn sẽ đi 1 đường dịch thuật liền, như món quà chờ... Noel. IN THE OTHER hand, when Joseph

left Russia, when he read for the first time in the West, at that poetry

festival in London, he may well have been quite surprised at the enthusiasm

of the audience. It is conceivable, even likely, that he had no inkling of

what to expect. Of course, though still young, he was not new to the game.

He had been translated, had become the object of what were in effect cultural

pilgrimages, had been pilloried by the state, was close to the last of the

great ones, Akhmatova. And then there were his readings in Russia (remember

Etkind's description, cited above). I suppose he was already a cult figure,

whatever that may mean, or well on his way to becoming one. So he was surely

aware of the hallucinatory effect of his performances. Even so, there was

no telling whether this would turn out to be exportable. Traumatized as Joseph

evidently was, that first reading at the Queen Elizabeth Hall at once set

him on the path. He gave reading after reading. He did not let the sound fade,

or himself go out of fashion, be lost sight of. He kept himself, the sound

of himself, current. In one respect, this can be seen as a triumph of the

will to survive, though he may also have needed constant exposure of this

sort to compensate for the loss of a native audience. And in any case, as

we have seen, he regarded it as his particular mission - though he might

have balked at putting it so grandly - to bring Russian to English. And beyond

that, of course, was the larger mission, on behalf of Poetry itself. And

there must have been a price to pay, that of privacy, of the seclusion most

artists need. Still, he also had the invaluable knack of being just himself.

And periodically, as at Christmas when he went to Venice, he became a "nobody

in a raincoat". Or do I exaggerate? Was he, in fact, misled? Did he misunderstand the interest his person or presence aroused? Perhaps it was more a matter of curiosity. He had become a sort of institution, America's Poet-in-Exile. And as for his odd English, well, away with it, who cared really. It had seemed to me, from the start, that Joseph was a great improviser. He had not quite anticipated the reception he received, but he adjusted readily enough to it. And as for his style of reading, well, as noted, he claimed it was simply the way poetry was read in Russia. But even his disingenuousness worked to his advantage. So, perhaps it was all a kind of improvisation. He relied on the challenge of live situations, on his wit and his wits, on language itself. Joseph had faith. He adopted a casual manner, even though the delivery of the poetry was quite the opposite to casual. He resisted being turned into a monument, an institution, although he himself raised monuments to those he regarded as his mentors: Tsvetayeva, Mandelstam, Akhmatova, Frost, Auden. Về mặt khác, khi Joseph rời

Nga, khi chàng đọc thơ lần thứ nhất ở Tây Phương, tại hội thơ ở London, chàng

làm sao mà không ngạc nhiên, trước thái độ niềm nở của khán thính giả. Cũng

dễ hiểu, bởi là vì chàng có hy vọng chi đâu. Lẽ dĩ nhiên, chàng không phải

tay mơ trong nghề chơi. Đã từng được dịch diệc, đã từng trải mùi đời, đã

từng bị VC Nga đọa đầy chẳng khác gì Akhmatova. Thành thử, khi đăng đàn đọc

thơ, chàng đã là 1 thứ tầm cỡ, một hình tượng văn hóa, một nhân vật thờ,

a cult figure, nhưng gì thì gì, chẳng làm sao biết, sau cùng sự đời sẽ ra

sao! Phút ấy Thùy tỉnh ngộ dưới mắt Kiệt nàng không là gì. Hắn cười trong cõi riêng. Từ bao giờ hắn vẫn sống trong cõi riêng, với nàng bên cạnh. Phát giác đột ngột làm nàng tủi hận nhưng giúp nàng cứng cỏi thêm trong thái độ lựa chọn. Hắn coi thường nàng trong bao lâu nay nàng không hay và hắn phải chịu sự khinh miệt rẻ rúng của nàng từ nay. Thùy đi ngang mặt Kiệt, vào giường. Vài phút nữa Kiệt đi. Kiệt trở về hoặc không trở về chẳng còn làm bận được đầu óc nàng. Giữa nàng và Kiệt tuyệt không còn một câu nào để nói với nhau. Hai người đã đứng hai bên một bức tường kính. Giấc ngủ đến với Thùy mau không ngờ. Kiệt đi nàng không hay. (1) Dante

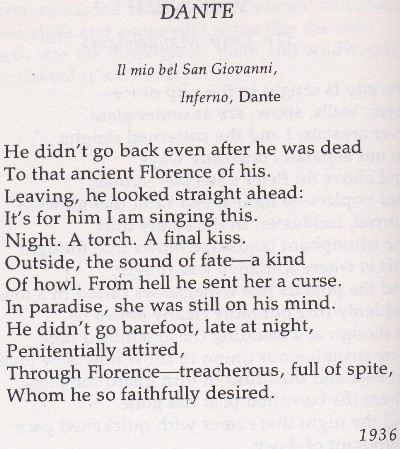

Chàng đếch thèm trở lại In August 1936, Akhmatova devoted

a poem to Dante, emphasizing as the archetypal poet in exile, playing the

same role as Ovid did in Pushkin’s work. Like Akhmatova's Petersburg, Dante's

Florence represents a way of life and thought. In his case it will be lost

to him because he was exiled for his beliefs. The poem may also be an indirect

allusion to Mandelstam, another poet in exile. Dante was forced to leave

his beloved city in 1302 after the victory of the opposing party. Several

years later he was offered the possibility of returning under condition of

a humiliating public repentance, which he spurned. He refused to walk "with

a lighted candle"-the ritual of repentance-even to be able to return to Florence.

Unlike Lot's wife, he refused to look back.

Dante Il mio bel San Giovanni Even after his death he did

not return (II, p. 117) In another of her lyrical portraits,

"Cleopatra" (February 1940), Akhmatova deals with the theme of a great figure

facing humiliation. Here she depicts an who chooses to end her life rather

than submit to authority: Cleopatra Alexandria's palaces

While refusing to accept suicide

as a solution to her own grief, Akhmatova describes the state of mind of

a great queen who does, rather than render unto Cesar what he wishes-her

submission. As in many of Akhmatova's poems, there is an implicit "prehistory."

Cleopatra is shown at the moment before her death. Antony has been defeated

by Augustus Caesar and has committed suicide, now Caesar wishes the glorious

Queen of Egypt to be paraded like a slave before him. In a few telling details,

Akhmatova reveals that rather than encounter self-imposed death with hysteria,

Cleopatra greets it with dignified restraint. In antiquity, Cleopatra's suicide

was viewed as an act of courage, but for a faithful ever in Christianity,

it was not a viable option. Instead, Akhmatova's "inner peace” and strength

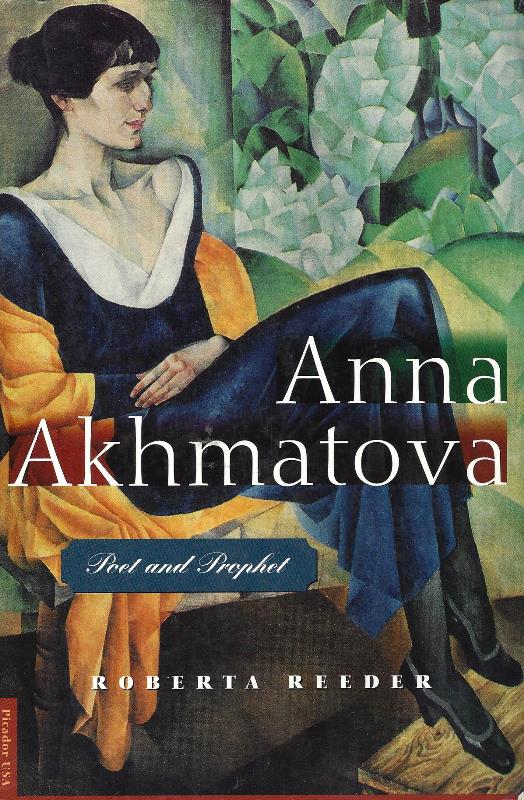

enabled her to endure. Akh: Thi sĩ, Tiên tri: The Great

Terror: 1930-1939 Brodsky had written his poem

to her [Akhmatova] earlier that year: … I did not see, will not see

your tears,

Bà sẽ viết về chúng tôi trong dáng nghiêng,

trên con dốc nghiêng... Chúng tôi ở đây, là "những dứa

trẻ mồ côi của Akh", gồm bốn đứa: Brodsky, Nayman, Rein và Bobyshev. I don't weep for myself now, (Bây giờ tôi không

khóc cho chính tôi With her usual gift for prophecy

and insight, she predicted destiny would soon Brodsky's ability to endure

adversity. One time, in 1962, Bobyshev

brought Akhmatova a poem he had written for along with a bouquet of five

beautiful roses. It was her birthday, and she was at Komarovo. Akhmatova

mentioned the roses on his next visit, saying, of them soon faded, but the

fifth bloomed extraordinarily well and created almost flying around the room."

Soon the young poets found out what "miracle" was-Akhmatova had written poems

to them. "The Last Rose" devoted to Brodsky, "The Fifth Rose" to Bobyshev,

and "Non-existence" to . The poem to Brodsky was the one she recited to Robert

Frost when he to see her. In it she asks God to let her live a simple life

and not share the fate of famous women in history like Joan of Arc and Dido.

She opens an epigraph containing a line from Brodsky: "You will write about

us on a " which appeared when Akhmatova's poem was first published, but disappeared

after Brodsky's trial. Brodsky had written his poem

to her earlier that year… Akhmatova: Kinh Cầu Chẳng có ai người cười nổi,

những ngày đó Tiếng còi tầu chở súc vật rú

lên Không phải tôi.

Ai đó đau khổ Akhmatova, có vẻ như được sửa soạn để đóng cái vai của bà, hơn hầu hết những nhà thơ cùng thời. Ngoài ra, vào lúc xẩy ra Cách Mạng, bà 28 tuổi , không quá trẻ để tin hay không tin, và cũng không quá già để biện minh cho nó. Sau đó, là 1 người đàn bà, trong vai “gái” [“cái” cũng được] thì cũng khó mà thổi Cách Mạng, hay kết án nó. Bà cũng không quyết định thay đổi trật tự xã hội…. Đọc bài viết của Brodsky về

Akhmatova, nữ thần thơ bi ai Nga, thì Gấu ngộ ra điều, tại sao mà GCC này

chịu không nổi, phải nói, tởm, cái giọng của đám VC ly khai, thứ ngôn ngữ

nhơ bẩn, “máu què”, thí dụ, cũng như cái giọng gà mái gáy của Sến, vẫn thí

dụ. Và trước đó, Brodsky giải thích: Đâu có phải cứ đụng tới chữ nghĩa, tới văn chương, tới thơ ca, là vãi nước đái ra, hoặc văng tục, hoặc gáy? Bearing the Burden of Witness: Requiem was born

of an event that was personally shattering and at the same time horrifically

common: the unjust arrest and threatened death of a loved one. It is thus

a work with both a private and a public dimension, a lyric and an epic poem.

As befits a lyric poem, it is a first-person work arising from an individual's

experiences and perceptions. Yet there is always a recognition, stated or

unstated, that while the narrator's sufferings are individual they are anything

but unique: as befits an epic poet, she speaks of the experience of a nation. The Word That Causes Death’s Defeat Kinh Cầu đẻ ra từ một sự kiện, nỗi đau

cá nhân xé ruột xé gan, và cùng lúc, nó lại rất là của chung của cả nước,

một cách cực kỳ ghê rợn: cái sự bắt bớ khốn kiếp của nhà nước và cái chết

đe dọa người thân thương ruột thịt. Bởi thế mà nó có 1 kích thước vừa rất

đỗi riêng tư vừa rất ư mọi người, rất ư công chúng, một bài thơ trữ tình

và cùng lúc, sử thi. Nó là tác phẩm của ngôi thứ nhất, thoát ra từ kinh nghiệm,

cảm nhận cá nhân. Tuy nhiên, trong lúc chỉ là 1 cá nhân đau đớn rên rỉ như

thế, thì nó lại là độc nhất: như sử thi, bài thơ nói lên kinh nghiệm toàn

quốc gia…. Đáp ứng, của Akhmatova, khi

Nikolai Gumuilyov, chồng bà, 35 tuổi, thi sĩ, nhà ngữ văn, trong danh sách

61 người, bị xử bắn không cần bản án, vì tội âm mưu, phản cách mạng, cho

thấy quyết tâm của bà, vinh danh người chết và gìn giữ hồi ức của họ giữa

người sống, the determination to honor the dead, and to preserve their memory

among the living…. Theo sự hiểu biết cá nhân của

Gấu, thì chỉ hai nhà thơ, sống thật đời của mình, không 1 vết nhơ, không

khi nào phải “edit” cái phẩm hạnh của mình, là Brodsky và ông anh nhà thơ

của GCC. Bảnh như Osip Mandelstam mà cũng phải sống cuộc đời kép, trong thế giới khốn nạn đó. Để sống sót, Mandelstam cũng đã từng phải làm thơ thổi Xì, như bà vợ ông kể lại, và khi những người quen xúi bà, đừng bao giờ nhắc tới nó, bà đã không làm như vậy: Nadezhda Mandelstam recalled how her husband Osip Mandelstam had done what was necessary to survive: To be sure, M. also, at the

very last moment, did what was required of him and wrote a hymn of praise

to Stalin, but the "Ode" did not achieve its purpose of saving his life.

It is possible, though, that without it I should not have survived either.

. . . By surviving I was able to save his poetry.... When we left Voronezh,

M. asked Natasha to destroy the "Ode." Many people now advise me not to speak

of it at all, as thou it had never existed. But I cannot agree to this, because

the truth would then be incomplete: leading a double life was an absolute

fact of our age and nobody was exempt. The only difference was that while

others wrote their odes in their apartments and country villas and were rewarded

for them, M wrote his with a rope around his neck. Akhmatova did the same,

as they drew-the noose tighter around the neck of her son. Who can blame

either her or M. Trong khi lũ nhà văn nhà thơ Liên Xô làm thơ ca ngợi Xì và được bổng lộc, thì M làm thơ ca ngợi Xì với cái thòng lọng ở cổ, và bài thơ “Ode” đó cũng chẳng cứu được mạng của ông. Người ta xúi tôi, đừng nhắc tới nó, nhưng tôi nghĩ không được, vì như thế sự thực không đầy đủ: sống cuộc đời kép là sự thực tuyệt đối của thời chúng ta. Tuyệt. Chỉ có hai nhà thơ sống sự thực tuyệt đối của thời chúng ta, bằng cuộc đời “đơn” của họ, là Brodsky và TTT! Etkind relates how this trial

pitted two traditional foes against each other, the bureaucracy and the intelligentsia.

Brodsky represented Russian poetry. The lot had fallen on him by

chance. There were many other talented at the time who might have been in

his place. But once the lot fell him, he understood the responsibility of

his position-he was no a private person but had become a symbol, the way

Akhmatova been in 1946, when she was picked out of hundreds of possible poets

punished, and became a national symbol of the Russian poet, as had become

that day. It was hard for Brodsky-he had bad nerves, a bad heart. But he

played his role in the trial impeccably, with dignity, without challenge,

and with fervor, calmly, understanding by the way he answered he evoked deep

respect not only from his friends but from those who once had been indifferent

to him or even hostile. Có nhiều nhà thơ có tài, có thể ở vào chỗ anh ta khi đó, Efim Etkind viết. Nhưng số phận đã chọn đúng anh ta, và ngay lập tức anh hiểu trách nhiệm về địa vị của anh - không còn là một con người riêng tư, nhưng trở thành một biểu tượng, như Akhmatova đã trở thành một biểu tượng quốc gia của người thi sĩ Nga, khi bà bị số phận lọc ra giữa hàng trăm nhà thơ, năm 1946. Thật quá nặng cho Brodsky. Ông có một bộ não tệ, một trái tim tệ. Nhưng ông đã đóng vai ông tại tòa án một cách tuyệt vời. Cuốn “Akhmatova, thi sĩ, tiên

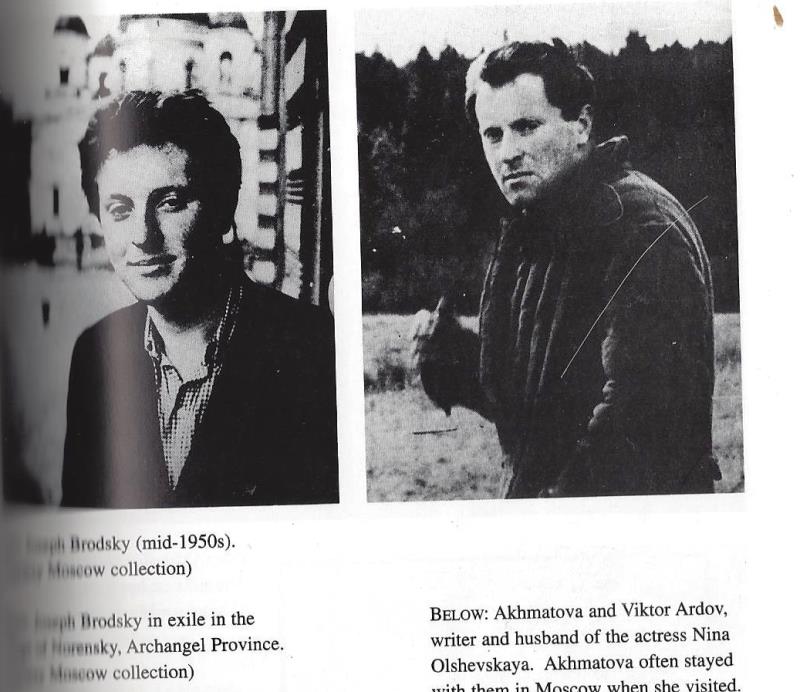

tri”, trên 600 trang, khổ lớn, dành 1 chương cho Brodsky [Joseph Brodsky: Arrest and Exile, 1963-1965],

kể lại chi tiết vụ án, và về “những đứa trẻ mồ côi của Akhmatova”, là đám

nhà thơ trẻ trong có Brodsky. GCC có tới ba, hoặc 4 cuốn,

khổng lồ về Akhmatova, cuốn trên, "Chữ đuổi Thần Chết chạy có cờ", "Nửa thế

kỷ Akhmatova..." cuốn nào cũng thú vị hết, hà hà!

Dante

Chàng đếch thèm trở lại Bài thơ trên, kỳ cục thay -

tuyệt vời thay - làm liên tưởng tới nhà thơ tội đồ gốc Bắc Kít, trong bài

thơ nhớ vợ; cũng cái giọng ngôi thứ nhất, cũng chỉ là riêng tư, mà trở thành

“sử thi” của lũ Ngụy. Bài thơ thần sầu nhất của Thơ Ở Đâu Xa: Bài Nhớ Thi Sĩ Đâu có phải tự nhiên mà đám sĩ quan VNCH lại phổ thơ, và đi đường tụng ca, khi còn ở trong tù VC. Mỗi ông thì đều có 1 bà vợ như vậy.

Văn xuôi Akhmatova: Nửa Thế Kỷ Của Tôi Đọc loáng thoáng, vớ được giai thoại này, lạ làm sao, làm nhớ đến giai thoại, về Shostakovich, thời gian thất sủng, không dám ngủ ở trong nhà, mà ở hành lang, chờ KGB tới bắt, để vợ con khỏi phải nhìn thấy cảnh tượng này. Trên Điểm Sách London, số 1, Dec 2011 có 1 bài hay lắm về ông, đúng hơn, về cái thế đi hai hàng của ông. Để thủng thẳng TV giới thiệu độc giả, coi có giống đám sĩ phu Bắc Hà không (1) In the mid-1920s attacks in the press against Akhmatova were crowned with success: Akhmatova was officially banned from publication. The resolution, however, was never made public or printed and Akhmatova learned of it only through an acquaintance: After my readings in Moscow (Spring 1924) the resolution regarding the cessation of my literary activity was put into effect. I was no longer published in journals or almanacs, or invited to literary evenings. I met Marietta Shaginyan on Nevsky Prospect. She said: "You're such an important person-the Central Committee passed a resolution about you-not to be arrested, but not to be published either." Vào giữa thập niên 1920, những cuộc tấn công nhắm vào Akhmatova đạt đến đỉnh cao chói lọi của nó. Bà chính thức bị cấm in ấn bất cứ 1 cái gì. Nhưng đếch ai đọc được cái lệnh này, vì là lệnh miệng từ Bắc Bộ Phủ Cẩm Linh. Bà chỉ biết đến nó, qua 1 người quen. Bà bạn quen này nói: Mi bảnh thật. Nhà nước bi giờ

ra 1 nghị quyết Đảng về mi: Hà, hà! In August 1936, Akhmatova devoted

a poem to Dante, emphasizing as the archetypal poet in exile, playing the

same role as Ovid did in Pushkin’s work. Like Akhmatova's Petersburg, Dante's

Florence represents a way of life and thought. In his case it will be lost

to him because he was exiled for his beliefs. The poem may also be an indirect

allusion to Mandelstam, another poet in exile. Dante was forced to leave

his beloved city in 1302 after the victory of the opposing party. Several

years later he was offered the possibility of returning under condition of

a humiliating public repentance, which he spurned. He refused to walk "with

a lighted candle"-the ritual of repentance-even to be able to return to Florence.

Unlike Lot's wife, he refused to look back. [Trong cuốn trên, có 1 bản dịch khác bài thơ "Dante"]

From

Russia With Love

Thơ Mỗi Ngày

GRIGORI DASHEVSKY From "Ithaca" The night approaches. Dusk drafts

on buildings The signs of a life without

past will emerge Ithaca is the time In a long puddle he sees: So should I, a pauper sitting The twilight pushes a heavy

box of reflection The soul goes home the way of

flesh, Old rags are stronger than old

life. -Translated from the Russian

by Valzhyna Mort Poetry, Nov 2014

Áo xưa dù nhàu cũng xin bạc đầu gọi mãi tên nhau TCS

(a) Notes on

Writing and the Nation Ghi chú về Viết và Nước. Salman Rushdie The nation requires anthems, flags. Nhà thơ bèn chìa ra: Cứt. (1) (1) Discord: Sự bất hòa. Không khứng giao lưu,

hòa giải. Rag: Giẻ rách. Từ "cứt", là mượn của cả hai, NHT và nhà thơ Nguyễn

Chí Thiện: Ông nhà thơ, thay vì làm thơ ca ngợi nhân ngày sinh nhật Bác,

thì bèn đi ị. Nhưng chưa thảm bằng trường hợp của chính nhà thơ

Văn Cao. * Con chim ousen [chim két] hót ở trong rừng Cilgwri. Rushdie viết, rất ít nhà thơ kết hôn sâu xa đằm

thắm với đất mẹ như nhà thơ R.S. Thomas, một nhà thơ dân tộc Welsh [a Welsh

nationalist], những vần thơ của ông tìm kiếm, bằng cách nhận ra, để ý [noticing],

khẳng định [arguing], làm thành vần điệu, huyền hoặc hóa, biến đất nước thành

một sinh vật rất ư là nồng nàn, rất ư là trữ tình. Tuy nhiên, cũng chính ông này, cũng viết: Sự hận thù mất nhiều thời gian Không phải tôi thù cái mảnh đất tàn nhẫn thô bạo

dã man mà tôi ra đời... Hate takes a long time Thảo nào, thằng cha Gấu thù chính nó, thù cái chất

Yankee mũi tẹt của chính nó!

Bosnia Tune

As you sip your brand of scotch, In the towns with funny names, In small places you don't know People die as you elect Too far off to practice love While the statues disagree, As you watch the athletes score, Time, whose sharp bloodthirsty

quill Joseph Brodsky: Collected Poems in English Note: Bài phỏng vấn này, từ

năm 2004, thú thực, GCC không nhớ, có đọc hay là không, hà, hà! Post lại trên TV, từ FB của

LMH, và lèm bèm sau. Tuy nhiên, trong bài viết về Brodsky, ký giả Mẽo, David

Remnick, có nêu ra trường hợp này rồi, về cái sự in tác phẩm xb ở hải ngoại

ở trong nước. Và cũng nhắc thêm trường hợp

chẳng tự nhiên gì, liên quan đến Võ Phiến vs Fils, hiện đang ì xèo trên mạng. Những đứa

con của trí tưởng Khoảng năm 1988, do sinh kế, gia đình tôi mở ngay một sạp báo trước ngõ. Chủ nhân đích thực, ông cán bộ nhà kế bên. Như một cách giữ chỗ, trước khi về hưu, và cũng muốn giúp đỡ gia đình nguỵ. Cư xá tôi ở vốn thuộc nhà nước cũ, đa số là công chức có nghề chuyên môn được nhà nước "cách mạng" cho lưu dụng, sau ba ngày cải tạo tại chỗ. Đó là những chuyện ngay sau

ngày 30/4/75. Thời điểm 1988-89 đã có chủ

trương "cởi trói" cho những văn sĩ. Có thể nhờ vậy, văn chương, văn nghệ

sĩ nguỵ được "ăn theo". Một số sách trước 1975, nay thấy tái bản, dưới một

tên khác. Do biết ngoại ngữ, tôi được một người quen làm nghề xuất mướn dịch

một số tác phẩm, như của nhà văn y sĩ người Anh, Cronin. Rồi một người quen,

trước 75 cũng có viết lách, nay làm nghề sửa mo-rát cho nhà xuất bản nhà

nước, cho biết, ông chủ của anh muốn tái bản, tác phẩm Hemingway, Mặt Trời

Vẫn Mọc do tôi dịch. Tới gặp, ông cho biết cần phải sửa. Thứ nhất, bản dịch

của tôi sử dụng quá nhiều tiếng địa phương, thí dụ như "bồ tèo", "xập xệ"...

Thứ hai, có nhiều chỗ dịch sai. Tôi về nhà coi lại, quả đúng như thế thật.

Trước 1975, sách dịch chạy theo

nhu cầu thương mại. Cứ thấy một tác giả ngoại quốc ăn khách, vừa được Nobel...

là đua nhau dịch. Hồi đó, tôi làm cho nhà xuất bản Vàng Son của ông Nhàn,

số 32 Nguyễn Bỉnh Khiêm, nhà in của linh mục Cao Văn Luận. Một chi nhánh

của nhà xuất bản Sống Mới. Trước đó, tôi đã dịch một cuốn về cuộc đổ bộ Normandie,

nhưng do cuốn phim Ngày Dài Nhất đang ăn khách, ông Nhàn cho đổi tên cuốn

sách, không ngờ lại trùng với bản dịch Ngày Dài Nhất của một nhà xuất bản

khác. Thế là mạnh ai dịch. Dịch hối hả, dịch chối chết, mong sao ra trước

kẻ địch! Cuốn Mặt Trời Vẫn Mọc cũng gặp

tình trạng tương tự. Hemingway đang ăn khách. Huỳnh Phan Anh, ông bạn tôi

"chớp" Chuông Gọi Hồn Ai. Tôi vớ "thế hệ bỏ đi", tuy rằng Mặt Trời Vẫn Mọc!

Ngồi ngay tại nhà in, dịch tới đâu thợ sắp chữ lấy tới đó. Đọc lại, ngượng chín người.

Thí dụ như câu: cuối năm thứ nhì (của cuộc hôn nhân): at the end of the second

year, tôi đọc ra sao thành: cuối cuộc đệ nhị chiến, at the end of the second

war! Sau đó, tôi làm việc với nhà

xb, sửa lại bản dịch, dưới sự "kiểm tra" của Nhật Tuấn, ông em Nhật Tiến.

Thời gian này, tôi quen thêm Đỗ Trung Quân, nhân viên chạy việc cho nhà xuất

bản nọ. Rồi qua anh, qua việc bán sách báo, qua việc dịch thuật... tôi quen

thêm một số anh em trẻ lúc đó viết cho tờ Tuổi Trẻ, như Nguyễn Đông Thức,

Đoàn Thạch Biền. Họ đều biết tôi, từ trước 75. Đoàn Thạch Biền trước 75 đã

viết cho Văn qua tên Nguyễn Thanh Trịnh. Tôi không còn nhớ rõ, ai trong

số họ, đề nghị tôi viết mục đọc sách cho Tuổi Trẻ. Bài đầu tiên, là về cuốn

Thám Tử Buồn, một truyện dịch của một tác giả Nga. Thảm cảnh của nước Nga

sau đổi mới. Băng hoại tinh thần và đạo đức đưa đến tội ác. Trong đó có những

cảnh như là con cháu đưa bố mẹ tới mộ, chưa kịp hạ huyệt, xác bố mẹ còn bỏ

trơ đó, đã vội vàng về nhà tranh đoạt "gia tài của mẹ". Bố mẹ trẻ bỏ nhà

đi du hí, đứa con bị chết đói, khi khám phá thấy miệng đứa bé còn cả một

con dán chưa kịp nuốt thay cho sữa! Cuốn tiếp theo, là Ngôi Nhà Của Những

Hồn Ma, của Isabel Allende. Bài điểm cuốn này cho tôi những

kỷ niệm thật thú vị. Đó là lần đầu tiên tôi đọc Isabel

Allende, nhưng "sư phụ" của bà, tôi quá rành. Có thể nói, cả hai chúng tôi

đều học chung một thầy, là William Faulkner. Do đó, được điểm cuốn Ngôi Nhà

là một hạnh phúc đối với tôi. Nó là từ "Asalom, Asalom!" của

Faulkner mà ra. Có tất cả mấy tầng địa ngục của Faulkner ở trong đó, cộng

thêm địa ngục "giai cấp đấu tranh": ông con trai, con hoang, vô sản, "mần

thịt" đứa chị/em gái dòng chính thống, con địa chủ. Địa chủ, ông bố cô gái,

chính là ông bố của tên cách mạng vô sản! Có những câu điểm sách mà tôi

còn nhớ đến tận bi giờ: Những trang sách nóng bỏng trên tay, run lên bần

bật, vì tình yêu và hận thù! Sau khi bài điểm

sách được đăng, tôi được một anh bạn làm chủ một sạp báo cho biết, mấy người

khách quen của anh đổ xô đi tìm tờ báo có đăng bài của Nguyễn Quốc Trụ! Lúc

này, nhờ "cởi trói" nên được xài lại cái tên phản động đồi trụy này rồi! Chưa hết. Sáng bữa đó, tới văn

phòng phía Nam của nhà xb Văn Học, trình diện ông nhà văn cách mạng Nhật

Tuấn. Ông chủ của ông chủ, tức Hoàng Lại Giang, chủ nhà xb,

vừa thấy mặt, bèn kêu cô kế toán lên trình diện, ra

lệnh, phát cho tên ngụy này liền một tí tiền, coi như tiền nhuận bút bài

viết cho cuốn sách Ngôi Nhà Của Hồn Ma. Ông biểu thằng Ngụy, bài hay

thiệt. Chính vì vậy mà có bài điểm cuốn thứ ba. Cuốn này là Gấu được ông

chủ "order"! Cuốn này đụng! Trong bài viết,

khi đọc lại trên báo, Gấu thấy có từ "nguỵ". Thật tình mà nói,

không biết biết do tôi viết, hay đã bị sửa. Có thể do tôi. Bởi vì, vào thời

điểm lúc đó, "Nguỵ" là một từ đám chúng tôi rất ưa dùng, có khi còn hãnh

diện khi nhắc tới, nếu may mắn được ngồi chung với dăm ba quan cách mạng.

Nhưng một khi xuất hiện trong một bài viết, nhất là về một tác giả như

Hoàng Lại Giang, vấn đề lại khác hẳn. Tôi nghỉ viết cho

Tuổi Trẻ sau bài đó. Một bữa đang đứng

bán báo, Đ. ghé vô. Anh là bạn Huỳnh Phan Anh, trước 75 làm giáo sư. Sau

cộng tác với tờ Tuổi Trẻ. Nói chuyện

vài câu, anh đưa tôi một mớ tiền. Hỏi, tiền gì? Trả lời, tiền

nhuận bút đưa trước. Hỏi viết báo nào? Anh mỉm cười: viết báo hải ngoại! Hóa ra là, lúc

đó có chủ trương làm báo hải ngoại, từ trong nước, do mấy quan cách mạng

cầm chịch. Bài viết, theo Đ., tha hồ "đập" nhà nước, y chang báo hải ngoại,

kẻ thù cách mạng, chắc vậy! Đúng vào thời

gian này, một khách hàng quen của sạp báo, nhờ tôi kiếm dùm bản dịch tiếng

Pháp Tội ác và Trừng Phạt của Dostoevsky.

Có rồi, như để trả ơn, anh úp úp mở mở chìa cho tôi xem một tờ báo Time,

đã được ngụy trang bằng một cái vỏ bọc, là trang bìa tờ Đại Đoàn Kết. Tôi

hỏi mượn, anh gật đầu. Trong số báo đó, có một bài essay nhan đề: Sách, những

đứa con của trí tưởng (Books, children of the mind). Bài trên Time, là nhân vụ cháy một thư viện nổi

tiếng ở Nga, hình như là thư viện St. Petersburg. Sự thiệt hại, theo như

tác giả bài báo, là không thể tưởng tượng, và "không thể tha thứ" được. Ông

tự hỏi tại sao lại xẩy ra một chuyện "quái đản"

như vậy? Rồi ông tự giải thích, cái nước Nga nó vốn vậy, và chỉ ở đó mới

có những chuyện quái đản như thế xẩy ra. Ông dẫn chứng: Thời gian thành phố

St. Petersburg bị quân đội Quốc Xã Đức vây hãm 900 ngày, dài nhất trong lịch

sử hiện đại; trong khi nhân dân thành phố lả vì lạnh và vì đói, tiếng thơ

Puskhin vẫn ngân lên qua đài phát thanh thành phố, cho cả nước Nga cùng nghe.

Nhưng theo ông, cũng chính nước Nga là xứ sở đầu tiên đưa ra lệnh kiểm duyệt

báo chí, và đưa văn nghệ sĩ đi đầy ở Sibérie... Ông còn dẫn chứng nhiều nữa.

Trong khi đọc bài báo, lén lút, những khi vắng khách hàng, nhìn những cuốn

sách đang được bầy bán trên sạp tôi chợt nhận ra một sự thực: chúng đều mới

tái sinh, từ đống tro than là cuộc phần thư năm 1975. Cuốn Khách Lạ Ở Thiên

Đường, của Cronin, do Gấu tui mới dịch, đang nằm kia, vốn đã được dịch. Nhiều

cuốn khác nữa, chúng đang mỉm cười nhìn tôi: Hà, tưởng gì. chúng mình lại

gặp nhau! Tôi mượn tác giả

tên bài viết, viết về nỗi vui tái ngộ, về cuộc huỷ diệt sách trước đó. Về

những đứa con của trí tưởng, có khi cần được tẩy rửa, bằng "lửa". Tuy đau

xót, nhưng đôi khi thật cần thiết. Tiện đà, tôi viết về những tác giả đang

nổi tiếng, và tiên đoán một cuộc phần thư thứ nhì sẽ xẩy ra, do chính họ,

tự nguyện, nếu muốn lịch sử văn học Việt Nam lại có một cuộc tái sinh! Đ. nhận bài, hí

hửng mang về. Hai ba ngày sau, anh quay lại, trả bài viết, nói, không được!

Nhưng thôi, tiền tạm ứng biếu anh! Hỏi, anh cho biết: ông chủ nhiệm của tờ

báo hải ngoại, sau khi đọc bài viết, đi gặp thủ trưởng, yêu cầu: nếu cho

đăng những bài như thế này, cho dù là ở hải ngoại, phải cấp cho ông một tờ

giấy chứng nhận, "nhà nước" đã cho phép ông làm, qua cương vị chủ bút. Nếu

không sau này, cả ông lẫn người viết đều đi tù! Lệnh "miệng' thì

được, bố ai dám thò tay ký một văn bản "chết người" như vậy! Đoàn Thạch Biền nghe kể chuyện,

chạy tới: để tôi, in trên tờ báo có mục anh phụ trách, hình như tờ Công Luận, ở ngay phía đối diện Bưu Điện,

khu có quán cà-phê đám văn nghệ sĩ thường la cà. Nhưng rồi cũng lại lắc đầu,

không được! Người viết thử lại một lần nữa, đem đến cho tờ Kiến Thức Ngày

Nay. Tuần sau trở lại, gặp một anh thư ký trẻ măng, kính cận dầy cộm. Anh

nhìn, ngạc nhiên ra mặt: ông là ai sao tôi chưa từng biết, chưa từng nghe

qua? Anh cho biết, lệ thường, bài được đánh máy hai bản, một để làm tài liệu,

một đưa đi sắp chữ. Bài của ông, chúng tôi phải đánh máy ba bản, một đưa

qua mấy anh bên Hội Văn Nghệ Thành Phố, để các anh duyệt, nếu cần, xin ý

kiến thành uỷ! Các anh cho biết, cho đăng, nhưng phải sửa rất nhiều đoạn! Tôi xin lại bài

viết. Bài viết, sau

đó, nằm trong tay một người viết thuộc ban chủ trương tờ Tuổi Trẻ lúc đó.

Anh nói: tôi giữ lại đây, hy vọng sau này có dịp đăng. Như một cách giúp

đỡ: vì anh có sạp báo, tôi đề nghị mỗi tuần anh điểm hết mấy cuốn sách mới

xuất bản, theo kiểu tóm tắt nội dung, không cần phê bình, toà báo sẽ trả

nhuận bút, theo giá biểu những cuốn sách. Nhưng liền sau đó, tôi gặp lại

một người bạn, và qua anh, gia đình chúng tôi đã thực hiện chuyến đi dài,

chạy trốn quê hương. Viết lại chuyện

trên, tôi bỗng nhớ những ngày làm việc tại nhà xb nọ. Tôi đã gặp ở đó, một

số văn nghệ sĩ Miền Bắc. Ngoài Nhật Tuấn, Hoàng Lại Giang, những người khác

đều không biết tôi, và tôi cũng chẳng biết họ. Nghĩa là hai bên chẳng có

chuyện gì để nói. Tôi vẫn còn nhớ thái độ thân thiện, cởi mở của những người

tôi đã từng trò chuyện, tôi vẫn còn nhớ những khuôn mặt trong sáng đầy tin

tưởng của những người bạn trẻ như Đoàn Thạch Biền, Đỗ Trung Quân, và nhất

là dáng ân cần khi đưa ra đề nghị cộng tác, của anh phụ trách tờ Tuổi Trẻ

(hình như tên Thức, không phải Nguyễn Đông Thức. Đó là thời gian còn Kim

Hạnh)... Những người viết

Miền Nam trước 1975, ở lại, hình như đều viết trở lại. Tôi có lẽ là người

đầu tiên được nhà xuất bản Văn Học đề nghị tái bản bản dịch Mặt Trời Vẫn Mọc. Tôi nhớ lại chuyện

trên, nhân Sông Côn Mùa Lũ, của Nguyễn Mộng Giác,

một tác giả hải ngoại, được "tái bản" ở trong nước. Trong bài viết

Perfect Pitch,

ký giả David Remnick kể lại lần ông gặp Joseph Brodsky,

vào năm 1987, hai tuần lễ sau khi nhà thơ được giải Nobel văn chương. Cuộc

gặp gỡ diễn ra tại căn nhà hầm (basement apartment), phố Morton Street, trong

khu Greenwich Village, New York. Đó là thời điểm bắt đầu chính

sách glasnost. Thơ của ông được xuất bản ở trong nước, lần đầu tiên, sau

hơn hai thập kỷ. "Ông không thèm giấu diếm, dù chỉ một tí, niềm vui của mình,

về chuyện này", nhà báo Remnick viết. Và nhà báo giải thích về niềm vui của

nhà thơ: Đối với một chính quyền đã cho xuất bản tác phẩm của ông, và của

những nhà văn nhà thơ "bị biếm" khác, điều này có nghĩa: trả

lại của cải bị ăn trộm, cho chủ nhân. Và David Remnick cho rằng: đâu cần

phải biết ơn kẻ trộm! Có người tự hỏi về ý nghĩa một

bộ sách như Sông Côn Mùa Lũ,

bầy bên cạnh Lênin tuyển tập, Nhật Ký Trong

Tù...., ở đây theo tôi, nếu có sự thất thế, tủi nhục, thì phần lớn

là thuộc về kẻ ăn trộm chứ không phải người bị mất trộm! Đâu cần phải biết

ơn kẻ trộm. Cũng viết thêm, những sự kiện

trong bài viết, trên, đều thực cả, GCC chẳng bịa ra 1 chuyện gì hết. Happy New Year I Miss All Of U & SAIGON NQT Brodsky by Tolstaya

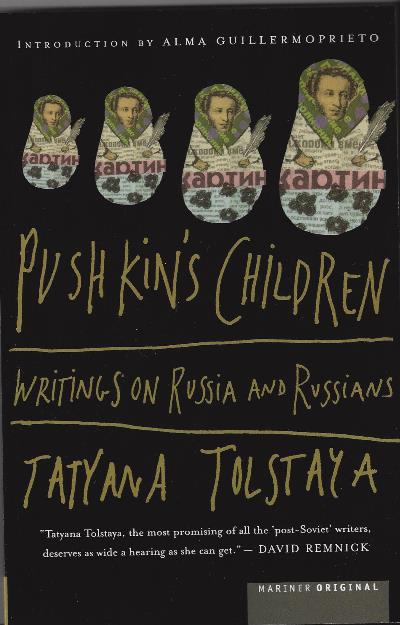

Trong bài viết này, Tolstaya

có kể về 1 lần trở lại Nga, tới 1 diễn đàn của đám Trẻ, chắc cũng giống như

… LMH tham dự buổi nói chuyện với Hà Nội, về Phố vẫn Gió, và bà [Tolstaya] quá sợ

hãi, vì cái sự tiếp đón bà, nhưng sau đó, bà hiểu, Moscow dành cho bà sự

đón tiếp… Brodsky, vì bà là... Brodsky với họ, và bởi là vì,

bà đã từng gặp Brodsky. Hà, hà! Y. Rein, là bạn

của Brodsky và cũng là một nhà thơ lớn, đã từng tuyên bố tại Moscow: Nước

Mỹ hãy nhớ lấy lời này. Brodsky là một tiếng nói Nga lớn lao nhất của thời

đại anh ta. Anh ta đến từ một thời đại tiếp theo những trại tù, những cấm

ngăn, một thời đại tự nuôi nó bằng văn chương trong khi chẳng còn chi, nếu

có chăng, chỉ là trống rỗng. Và anh luôn luôn là số một của chúng tôi. I met him in 1988 during a short trip to

the United States, and when 1 got back to Moscow 1 was immediately invited

to an evening devoted to Brodsky. An old friend read his poetry, then there

was a performance of some music that was dedicated to him. It was almost

impossible to get close to the concert hall, passersby were grabbed and begged

to sell "just one extra ticket." The hall was guarded by mounted police-you

might have thought that a rock concert was in the offing. To my utter horror,

I suddenly realized that they were counting on me: I was the first person

they knew who had seen the poet after so many years of exile. What could

I say? What can you say about a man with whom you've spent a mere two hours?

I resisted, but they pushed me onto the stage. I felt like a complete idiot.

Yes, I had seen Brodsky. Yes, alive. He's sick. He smokes. We drank coffee.

There was no sugar in the house. (The audience grew agitated: are the

Americans neglecting our poet? Why didn't he have any sugar?) Well,

what else? Well, Baryshnikov dropped by, brought some firewood, they lit

a fire. (More agitation in the

hall: is our poet freezing to death over there?) What floor does he

live on? What does he eat? What is he writing? Does he write by hand or use

a typewriter? What books does he have? Does he know that we love him? Will

he come? Will he come? Will he come? He had an extraordinary tenderness

for all his Petersburg friends, generously extolling their virtues, some

of which they did not possess. When it came to human loyalty, you couldn't

trust his assessments-everyone was a genius, a Mozart, one of the best poets

of the twentieth century. Quite in keeping with the Russian tradition, for

him a human bond was higher than Justice, and love higher than truth. Young

writers and poets from Russia inundated him with their manuscripts-whenever

I would leave Moscow for the United States my poetic acquaintances would

bring their collections and stick them in my suitcase: "It isn't very heavy.

The main thing is, show it to Brodsky. Just ask him to read it. I don't need

anything else- just let him read it!" And he read and remembered, and told

people that [he poems were good, and gave interviews praising the fortunate,

and they kept sending their publications. And their heads turned; some said

things like: "Really, there are two genuine poets in Russia: Brodsky and

myself." He created the false impression of a kind of old patriarch - but

if only a certain young writer whom I won't name could have heard how Brodsky

groaned and moaned after obediently reading a story whose plot was built

around delight in moral sordidness. "Well, all right, I realize that after

this one can continue writing. But how can he go on living?" Ông không tới với nước Nga,

nhưng nước Nga đến với ông. Nhà thơ Nga kỳ cục không muốn bám rễ vào đất

Nga. Ai

cho phép mi là thi sĩ?

Hai tên Do Thái, Two Jews AN INVOLUNTARY exile, Joseph

was a kosmopolit, more avid for world culture than he was curious

about Christianity. The Jew- as-writer, it seems to me, is committed to language

as such, to the living language. He does not write for the future, even if

his writing is "ahead of its time". Nor does he write out of reverence for

the past: past and future can take care of themselves. Joseph, of course,

was engaged in something else as well, making the two languages more equal,

adding, subtracting, but above all mixing. Even before he became a wanderer,

Joseph was a transgressor. As a translator, in the wider sense, he crossed

and recrossed frontiers. "All poets are Yids", said Tsvetayeva.

Joseph dispensed with the supposed privileges of victimhood. Jewishness, inescapably identified with persecution, was not likely to appeal to him. He made light of exile, stressing the gains both material and spiritual or intellectual, minimizing the losses. He was clearly scornful of those intellectuals who gathered periodically to discuss such issues, insisting that while the delegates talked, under the auspices of this or that foundation, others were suffering on a scale and to a degree that rendered their complaints laughable, even contemptible. He was not a whiner, and he was quite intolerant of the pervasive "culture of complaint". Naturally, this did nothing for his popularity among fellow exiles. In short, if he made a career, he did not actively make it out of the sufferings he had endured as a Jew or as the victim of a regime that still had totalitarian aspirations. Là 1 tên lưu vong miễn cưỡng

- bị VC Liên Xô tống xuất, như cas của Điếu Cày, thí dụ, tao phải kiện lũ

VC - Joseph [Brodsky] là "người của bốn phương", thèm khát văn hóa thế giới

hơn là tò mò về Ky Tô Giáo. Là 1 tên nhà văn Do Thái đối với tôi, là xuống

thuyền., dấn thân... với ngôn ngữ, như thế, tức là với ngôn ngữ đang còn

sống. Ông không viết cho tương lai, ngay cả khi ông phán, viết "trước thời

của nó". Ông cũng đếch viết để dựng dậy cái xác chết là quá khứ [Ngụy, thí

dụ, như tên GCC]. Quá khứ với tương lai, chúng tự lo cho chúng, đếch cần

đến tớ. Lẽ dĩ nhiên, Joseph vướng mắc với 1 cái gì khác.... "WHEN YOU SPEAK, cherish the thought of the secret

of the voice and the word, and speak in fear and love, and remember that

the world of the word finds utterance through your mouth. Then you will lift

the word." This is from Martin Buber's Ten Rungs, Collected Hasidic Sayings

(I947), a section entitled, "Of The Power Of The Word". Later, in "How To

Say Torah", the compiler warns: "You must cease to be aware of yourselves.

You must be nothing but an ear that hears what the universe of the word is

constantly saying within you. The moment you start hearing what you yourself

are saying, you must stop." And further: "[The proud] are reborn as bees

... that hum and buzz: 'I am, I am, I am.'" Let me try something! He was not meek in his fatalism,

his resignation. Rather, he was fierce, even angry. Like a moralist. But

this anger, which sometimes showed itself in his encounters with the press

or others, was not manifest in his writing, in that which was destined to

remain. Language, as written down, demanded more of him. A certain ceremony

or decorousness was required. But he did not, as I sometimes supposed, hide

behind it. He just paid his dues to language and earned the right to import

more and more of the whole man. This apprenticeship I am not

being captious, merely speculating about Joseph's approach to the business

of writing. His vision of the self was a useful one. Perhaps, after all,

I was misled when, in the early seventies, I conjectured that "His refusal

to play any part other than himself should protect him against blandishments

in the West, as he was, in a sense, protected against pressures of conformism

in the Soviet Union by the refusal of the orthodox literary establishment

to acknowledge his artistic existence." The second part of that statement

is, in any case, tautologous. And the trouble with the rest of it is that

I was probably fearing Nếu Joseph [HV] né “lời của

Chúa”, có lẽ là vì anh cảm thấy “thế kỷ 20 mệt nhoài, kiệt quệ những khả

hữu cứu chuộc, và đụng độ với Tân Ước”. Chúa Ky Tô không đủ, Freud đếch đủ,

Marx đếch đủ [đừng đọc giọng Trung Kít nhe!], hiện sinh không, và Phật cũng

không…. Tất cả chỉ là những phương tiện để minh chứng, xác minh, chứng thực…

Lò Thiêu, không phải để tránh nó. Để tránh nó, chỉ có “10 điều giáo lệnh”,

thích hay không thích. Chỉ có Lời – 10 điều- giữa chúng ta và sự chiến thắng

của Cái Ác Bắc Kít! Brodsky Remembered YESTERDAY I received a card

with details of the memorial service for Joseph, to take place in New York

City, in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, on 8th March. I try to let

myself feel what I am feeling. But I am cautious too. After a month, I still

do not think of him as dead. That is, I do, but only when I oblige myself

to imagine him among the other dead. Family members, a friend or two. The Cathedral of St. John the

Divine, 112th and Amsterdam, New York City, \ Lucas Myers, one of my oldest

friends, from Cambridge days, lived at ro6th and Amsterdam. It was with him

that I used to stay. Joseph didn't want people to

fuss over him and he'd no use for self-pity. But am I fussing? You can't

actually fuss over the dead. Although there is, perhaps, an element of retrospective

fussing, insofar as they then seem not quite so dead. As for self-pity, or

rather the absence of it, this made a clean break possible. There was nothing

death could hold over his head. He was not intimidated by it. His life, more

than most lives, was a preparation for it. He was familiar with it, which

is not to say he was a thanatologist. There was nothing actually morbid about

his dialogue with death. Sometimes it was almost breezy. Note: Buổi tưởng niệm Brodsky,

được nhắc tới ở đây, Tin Văn có nhắc tới, khi trích dẫn bài tưởng niệm ông,

trên tờ Người Nữu Ước: Death will come and will find

a body (Chết sẽ tới và

sẽ thấy một xác thân Tuy sống lưu vong gần như suốt đời, ông được coi là nhà thơ vĩ đại của cả nửa thế kỷ, và chỉ cầu mong ông sống thêm 4 năm nữa là "thế kỷ của chúng ta" có được sự tận cùng vẹn toàn. Ông rời Nga-xô đã hai chục năm, cái chết của ông khiến cho căn nhà Nga bây giờ mới thực sự trống rỗng. Ông sang Mỹ, nhập tịch Mỹ, yêu

nước Mỹ, làm thơ, viết khảo luận bằng tiếng Anh. Nhưng nước Nga là một xứ

đáo để (Chắc đáo để cũng chẳng thua gì quê hương của mi...): Anh càng rẫy

ra, nó càng bám chặt lấy anh cho tới hơi thở chót. Nhớ Joseph [không có ly cà phê kế bên] Hôm qua, tớ nhận được 1 tấm cạc, về buổi

tưởng niệm Jospeph… tớ cố “mình lại bảo mình” đang cảm thấy như thế nào.

Nhưng tớ “cũng” cẩn trọng. Sau cả tháng, tớ vưỡn chưa làm sao nghĩ, Joseph

đã chết! Họ vẫn còn và Em vẫn còn MT CT TTT DT Và Em Đài Sử Note:

Tuyệt cú. Thần cú! First Meeting: My Unreliable Memory His trial, in Leningrad, in

February 1964, and the sentence of five years' hard labor for "social parasitism",

meaning not so much political dissent, as an unorthodox or unconventional

style of life - in a totalitarian state, the distinction in any case was

academic - had attracted international attention. The trial itself included

some memorable exchanges between the accused and the court, which were bravely

noted down at the time and widely reported in the West. Perhaps the most

notorious example: JUDGE: Who recognized you as

a poet? Who enrolled you in the ranks of poets? Do what he might to deflect questions about the trial, Joseph could not prevent its becoming an ingredient in the legend constructed around him. ("Legend", I hear him exclaim, as he did once when questioned about Solzhenitsyn, "what legend?" Vụ án của ông, tại Leningrad Tháng

Hai, 1964, và bản án, 5 năm lao động khổ sai vì là tên ăn hại

xã hội, không nặng về mặt bất đồng chính kiến với nhà nước, nhưng quả là

đã gây sự chú ý trên toàn thế giới. Ai xác nhận mi là thi

sĩ. Ai đưa mi vào hàng ngũ những nhà thơ? Ui chao, tui ná thở. Cái sự nghiêm

trang, thành thực, cù lần – nếu có thể gọi – thì không làm sao mà nghi ngờ

được, ở đây. Theo GCC, Brodsky,

khi trả lời VC Liên Xô, như trên, là do thực tình ông tin, ông là thi sĩ,

là do ông Trời quyết định! Nên nhớ, Brodsky

là dân Ky Tô, thơ của ông, đầy chất Ky Tô. Ngay cả cái chuyện ông bị chúng

bắt, là cũng do ông Trời quyết định. David Remnick giải thích thật

tuyệt thái độ của Brodsky, khi ra tòa, trong 1 bài viết đăng trên “Người

Nữu Ước”, GCC, lần đầu tiên đọc, lần đầu tiên biết đến Brodsky, những ngày

mới ra hải ngoại, và bèn dịch liền tù tì, với vốn tiếng Anh ăn đong của mình,

hà, hà! Có nhiều nhà thơ có tài, có

thể ở vào chỗ anh ta khi đó, Efim Etkind viết. Nhưng số phận đã chọn đúng

anh ta, và ngay lập tức anh hiểu trách nhiệm về địa vị của anh - không còn

là một con người riêng tư, nhưng trở thành một biểu tượng, như Akhmatova

đã trở thành một biểu tượng quốc gia của người thi sĩ Nga, khi bà bị số phận

lọc ra giữa hàng trăm nhà thơ, năm 1946. Thật quá nặng cho Brodsky. Ông có

một bộ não tệ, một trái tim tệ. Nhưng ông đã đóng vai ông tại tòa án một

cách tuyệt vời. Theo dòng suy nghĩ, như trên,

thì đại thi sĩ Kinh Bắc, được Ông Trời cho ra đời, là để đụng cú viết tự

kiểm, và để phán, tao đéo viết! Tòa án: Công việc của anh? Một người làm chứng nói con

trai của anh ta đã rơi vào ảnh hưởng xấu xa của Brodsky, và đã bỏ việc làm,

quyết định nó cũng là thiên tài. Cũng người này đã nói, thơ của Brodsky,

những suy tư về thời gian, sự chết, tình yêu, có vẻ chống Xô-viết. "Bài nào?",

Brodsky ngắt lời. "Hãy kể tên một bài". Người đó chịu thua. Vigdorova viết thư cho Chukovskaya

về phiên tòa: Có thể một ngày nào đó, anh ta là một nhà thơ lớn. Nhưng làm

sao tôi quên nổi vẻ mặt của anh ta, lúc đó - không trông mong một sự trợ

giúp, ngạc nhiên, khôi hài, và thách đố, tất cả cùng một lúc".

The Gift

"Thiên tài" Brodsky: Những hạnh của bất hạnh Joseph Brodsky and the fortunes of misfortune. А что до слезы из глаза—нет на нее

указа, ждать до дргого раза. Meaning, roughly: “As for the tears

in my eyes/ I’ve received no orders to keep them for another time.”

… cities one

won't see again. The sun [Có những thành phố mà ta sẽ

chẳng nhìn thấy nữa. Mặt trời dát vàng lên những khung cửa sổ gía lạnh. Nhưng

cũng vậy thôi, [Từ đấy trong tôi bừng nắng

hạ], nhưng thôi, kệ mẹ mọi cái thứ rác rưởi, kệ mẹ cả lò chủ nghĩa Cộng Sản,

[In spite of all Communism], St. Petersburg của nhà thơ vẫn luôn luôn là

“thành phố đẹp nhất trên thế giới”. Sự trở về, là không thể, trước tiên là

vì chế độ chính trị khốn kiếp đó, lẽ tất nhiên, nhưng sâu thẳm hơn, là yếu

tố tâm lý này: “Con người chỉ dời đổi theo một chiều. Và chỉ từ. And only

from. Từ một nơi chốn, từ một ý nghĩ đã đóng rễ ở trong đầu, từ chính hắn

ta hay là y thị… nghĩa là, hoài hoài dời xa cái điều mà con người đã kinh

nghiệm, đã từng trải. Nghĩa địa Do Thái ở Leningrad

Gấu Cà Chớn nhớ là, đọc đâu

đó, hình như trên net, khi Nguyễn Đình Thi sắp sửa đi xa, ông con ghé tai

ông bố hỏi, bi giờ, bố tính sao, tính vô Văn Điển [hay Mai Dịch gì đó, nơi

dành riêng cho đám VC chóp bu nằm, sau khi chết], cho có bạn, hay là kiếm

chỗ khác… NDT quắc mắt, phán, KHÔNG, ông con mừng quá, tính đứng lên, thì

ông bố níu lại, thôi, con ạ, làm như thế là mày mất phần thịt đấy, cứ chôn

tao ở chỗ nhơ bửn, cứt đái đó, cũng xứng với tao vậy! Mất "phần thịt", là Gấu phịa

ra, khi nhớ tới bà nội của Gấu, suốt đời, mong nhìn thấy thằng cháu được

15 tuổi, được coi là 1 suất đinh, và "được" có phần thịt chia, vào những

dịp lễ lạc lớn trong họ! Reading in Iowa City, Iowa SOME YEARS ago, Joseph came

to Iowa City, the University of Iowa where I directed the Translation Workshop,

to give a reading; I was to read the English translation. At the end, he

was asked a number of (mostly loaded) questions, including one (alluded to

earlier) about Solzhenitsyn. "And the legend which had been built around

him?" His answer managed to be both artfully diplomatic and truthful: "Well,

let's put it this way. I'm awfully proud that I'm writing in the same language

as he does." (Note, again, how he expresses this sentiment in terms of language.)

He continued, in his eccentrically pedagogical manner, forceful, even acerbic,

but at the same time disarming, without any personal animus: "As for legend

... you shouldn't worry or care about legend, you should read the work. And

what kind of legend? He has his biography ... and he has his words." For

Joseph a writer's words were his

biography, literally! Brodsky certainly considered

himself to be - and it is increasingly clear that he was - in the grand line

that included Anna Akhmatova, Boris Pasternak, Osip Mandelstam and Marina

Tsvetayeva. Even I sensed this, despite my ambivalence about his poetry.

Indeed, the continuity embodied in his work accounts, in part, for my uncertainty:

I have tended to rebel against grand

traditions. But perhaps this is to exaggerate. At times I hear the music,

at other times the man, even if, as a rule, I do not hear them both together

... Mary now speaks to Christ: How can I close my eyes, Christ speaks to her in turn: It is true that, as I listen to or read the English, I hear the Russian too, in Joseph's rendition. I even see Joseph, his hands straining the pockets of his jacket, his jaw jutting, as though his eye had just been caught by something and he were staring at it, scrutinizing it, while continuing to mouth the poem, almost absent-mindedly, that is, while the poem continues to be mouthed by him. His voice rises symphonically: Syn ili Bog (Son or God), "God" already (oddly?) on the turn towards an abrupt descent; and then the pause and a resonant drop, a full octave: Ya tvoi (I am thine). And the poet, with an almost embarrassed or reluctant nod, and a quick, pained smile, departs his poem. Note: Gấu post bài này, quá

thú, tất nhiên, còn là để cám ơn một vì độc giả, đã sửa giùm đoạn thơ trong

bài, liên quan tới Chúa Hài Đồng, vì cũng sắp đến Giáng Sinh rồi! For Joseph a writer's words

were his biography, literally! Với Joseph, những từ của nhà

văn viết ra, là tiểu sử của người đó rồi Rõ ràng là Joseph coi mình thuộc

dòng cực sang, của những nhà cực bảnh, của truyền thống "nhớn", trong có

Anna Akhmatova, Boris Pasternak, Osip Mandelstam and Marina Tsvetayeva….

Tôi, [Daniel Weissbort] nhiều lúc muốn nổi loạn chống lại những truyền thống

lớn, nhưng có lẽ, chỉ là cường điệu… The

Brodsky Winners! Maria Sozzani Brodsky Son of Man and Son of God Tuesday, July 29, 2014 4:11

PM Thưa ông Gấu, Nguyên tác: Christ speaks to her in turn: Theo tôi, nên dịch như sau: Christ bèn trả lời: Best regards, DHQ Phúc đáp: NQT Verrà la morte e avrà i tuoi occhi.- Cesare Pavese From

Russia With Love

From

Russia With Love

"Tenderly Yours" IT IS HIS tenderness, in particular,

that I recall. He verbalized it, without embarrassment, making frequent use

of the word itself, which, to say the least (also a favorite Brodskyan expression),

is not much employed in Anglo-Saxon male society. And it is tenderness I

feel for him now. He ended his letters with a "kisses, kisses" or "tenderly

yours", and even on the phone, instead of good-bye, there'd be a brisk yet,

yes, tender: "kisses, kisses!" And then he'd wait, never in a hurry to break

off. (This may sound sentimental, but maybe he was for ever saying goodbye

for the last time.) Although by many whose paths he crossed he is remembered

as abrasive, pugnacious, he displayed an unostentatious strength, a tender

strength.

Here was something I had not noted: his strength or courage. Reading recently about his time in the Arkhangelsk Region (he was sentenced to five years, in I964, but released after twenty months of exile), I at first found it hard to reconcile the modest, rumpled, even somewhat disreputable if cocky figure with the man of principle, of valour. But then I understood that it was this courage that informed his personality. It was so much a part of him that one took it for granted. At least, I had so taken it. As if I were too close to see what was evident to others, even if fate had been immeasurably kinder to me than to him. It was something of a mystery to me that I could not love the poems as I did the man. Indeed, the poetry almost got in the way, as if I was jealous of his art, as of a rival for his affection! The poetry, even if he identified fully with it, represented his mission rather than himself, having as much to do with the language or with history ... I suppose I should make a distinction between the two. His preoccupation with language - Russian, of course, but also English, which he was in the process of idiosyncratically making his own - I shared. It was the glare of the power-and-the-glory, from which I shielded myself. Yes, I have begun to realize, after his death, that courage was the catalyst ... Clichés are knocking at the door! It is rather that there was a sudden awareness of the whole man, whereas I'd seen only pieces before. The loss was overwhelming! I suppose that is why I am writing now, trying to keep the awareness intact, not allowing it to fade prematurely. As if it would? Still, I want my quotidian self, which has no option but to negotiate with the world, to absorb it. It? Joseph. Our paths crossed at festivals and conferences. For instance, in 1979, at the University of Maryland, a "Symposium of Literary Translation and Ethnic Community" [sic!], we were on a panel. The panellists sat in a row; on the platform, at a long table. A "dialogue" between translators and translatees was supposed to take place ... Joseph and I meet by chance at breakfast. A vast self-service canteen. Joseph asks the woman behind the counter if she has any stronger coffee. She doesn't understand. He capitulates: "OK, make it regular." We go to a table, and he talks briefly about so-called "regular" American coffee. (I've come rather to like this innocuous beverage, which looks but doesn't really taste like coffee.) He lights a cigarette - you could still smoke on campuses then - and presses his hand to his chest, grimacing. A few moments later he lights up again ... He underwent his first heart surgery in December 1978. I felt the closeness of his death, certainly. He lived with it every day. So, why didn't he stop smoking? When I was diagnosed with cancer of the mouth, in 1982, I at once quit smoking, far too frightened not to. For Joseph, not quitting was even more suicidal. Was it his courage, paradoxically, that allowed him to continue smoking? Or perhaps, he did not love himself enough, did not value his own life enough. More precisely, his individual life? Or perhaps he just enjoyed living dangerously? To live meant to live dangerously. Bồ tèo, bồ tèo! Đúng là từ của Joseph [Huỳnh

Văn], như Gấu còn nhớ được! [Dịch nhảm, trong khi nhớ bạn.

Bài viết này, sẽ dịch liền, cũng thật là thú vị. Bạn, và còn là dịch giả,

của Brodsky, Daniel Weissbort nhớ lại, bạn của mình, khi được dịch qua tiếng

Anh, như cái tiểu tít cho thấy: Joseph

Brodsky trong tiếng Anh, in English] Joseph trải qua cuộc giải phẫu

tim, lần thứ nhất Tháng Chạp, 1978. Rõ ràng là tôi cảm thấy bạn của mình

cận kề cái chết. Anh sống với nó mọi ngày. Nếu thế, tại sao không bỏ hút

thuốc? Khi tôi biết mình bị ung thư, là bèn bỏ hút thuốc lá lập tức. Trường

hợp Joseph, đúng là quá cả tự sát! Cái vụ Điếu Cày bị bắt cóc đi

Mẽo, thẳng từ trại giam VC, làm GCC nhớ đến trường hợp Brodsky. Ông “có hẹn

với nhà nước Liên Xô tại Đồn Công An”. (1) Tới, chúng chìa ra cái đơn, bắt

ký vô, ông biểu, tao đâu có muốn rời xa Gấu Mẹ Vĩ Đại; chúng hăm, sẽ nóng

lắm đấy; nhưng tao đâu có bà con ở nước ngoài, chúng nói, có rồi, nhà nước

lo hết rồi, mày phải gọi ông ta bằng… chú! (1) "Vĩ Đại Thay, Là Đồn Công An! 'What a great

thing is a police station! [Phu quân tôi, nhà thơ] Mandelstam

thường nhắc câu trên, của Khlebnikov. Không hiểu Yankee mũi lõ, qua

cái loa tiếng Vịt của chúng, có đọc Tin Văn hay là không, giả như có đọc,

thì Gấu cũng chẳng lấy đó làm hãnh diện, nhưng chúng có đi 1 đường phân bua,

Điếu Cầy gật đầu, khi được hỏi, đi Mẽo, nhé? Bất giác bèn nhớ tới lời bà chị, cả lò nhà mày là CS, ra ngoài đó liệu liệu mà viết Cả lò Bắc Kỳ làm nô lệ cho thằng Tẫu, thì có! Vậy mà bầy đặt "thoát Trung"! NQT Brodsky chẳng hề muốn lưu vong,

hay được Mẽo bốc. Nhưng số kiếp của ông [do ông chọn], đi là đi 1 lèo, không

nhìn lại, như Bengt Jangfeldt đã từng đi 1 bài thần sầu về

ông: Joseph Brodsky: Người hùng Virgil: Đi để mà đừng bao giờ trở về. [A

Virgilian Hero, Doomed Never to Return Home]. (1) Trước khi rời

nước Nga, Brodsky viết cho Bí thư Đảng Cộng-sản Liên-xô, Leonid Brezhnev: