|

My Letter to the World

Because I could not stop for Death -

He kindly stopped for me - The Carriage held but just Ourselves - And Immortality. Em không thể ghé thăm Thần Chết Nên dịu dàng Người đến đưa Em Cỗ xe lăn bánh êm đềm Người, và Bất Tử cùng Em lên đường K dịch Note: “Mùa gặt chót” là tuyển từ toàn tập, gồm 567 bài, rút ra từ 1,775 bài. Bài Intro, thật là tuyệt. Gấu thú thực, không làm sao đọc được thơ của bà này. Đây là cú thử chót! A Word that breathes distinctly Has not the power to die Một Từ mà thở một cách rành mạch Không có sức mạnh để chết My Letter to the World

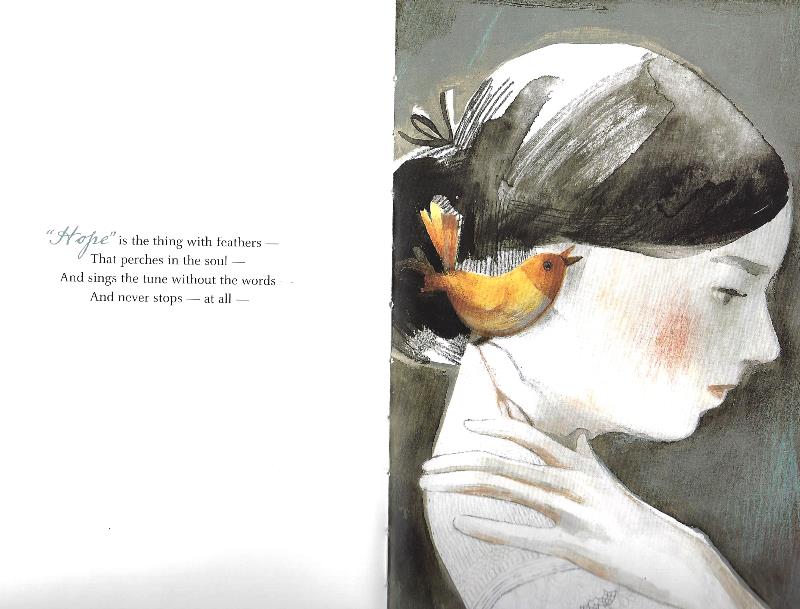

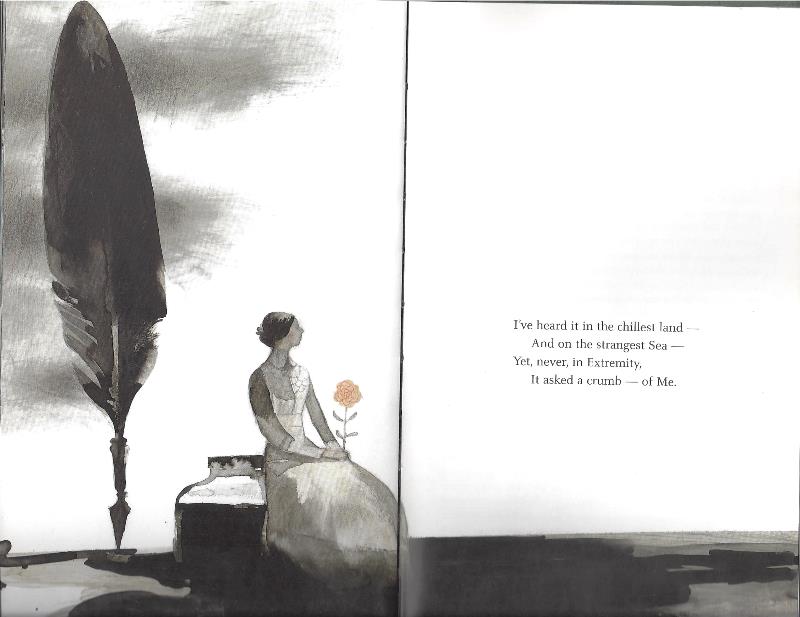

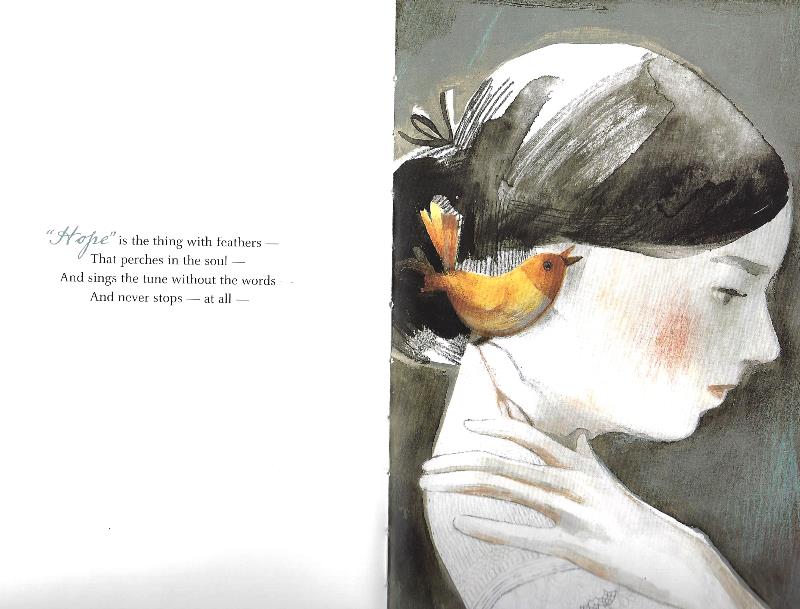

Hy Vọng là một loại Làm bằng lông chim trời Đậu cành linh hồn hót Mãi giai điệu không lời

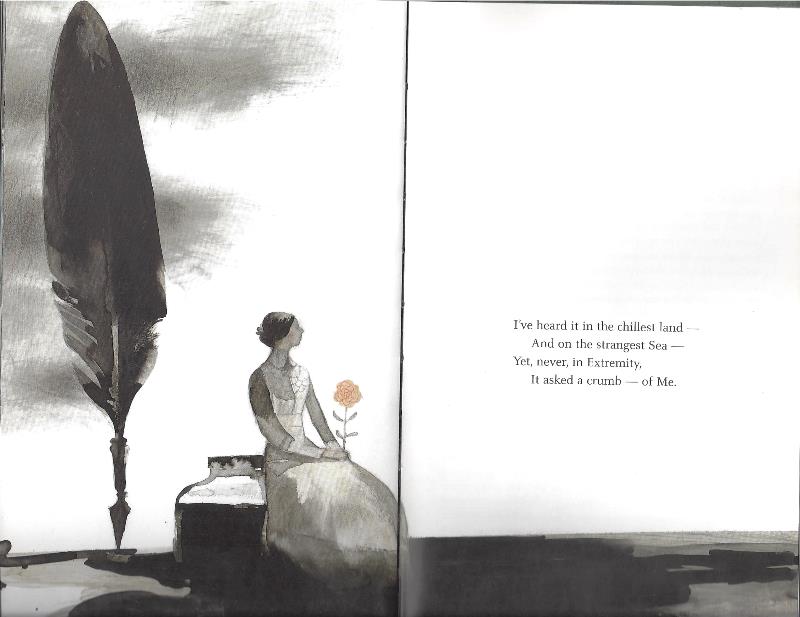

Nó hót nơi đất lạnh

Véo von ngoài biển xa Nhưng trong Tận Đau Đớn Câm đòi một mảnh Ta Tks. NQT

CHINESE BOXES AND PUPPET THEATERS Consciousness is the only home of which we know.

-DICKINSON

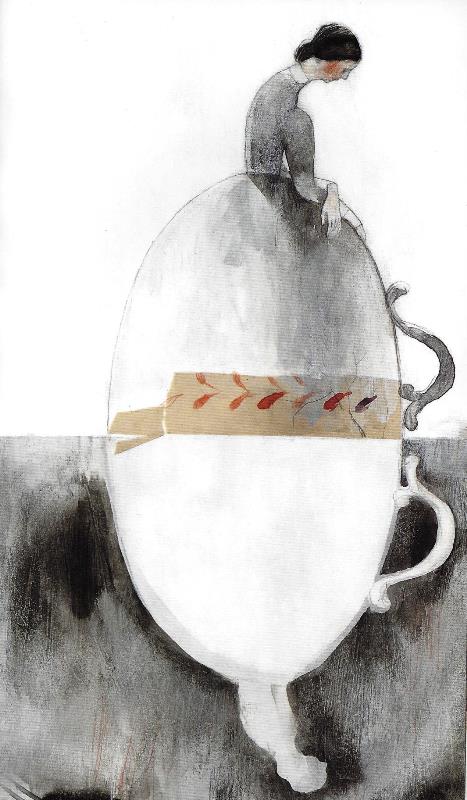

Two images come to mind when I think of Emily Dickinson's poems: Chinese

boxes and puppet theaters. The image of boxes inside boxes has to do with

cosmology, and theaters and puppets with psychology. They're, of course,

intimately related. The intimate immensity of consciousness is Dickinson's constant preoccupation. I imagine her sitting in her room for hours on end, with eyes closed, looking inward. To be conscious is already to be divided, to be multiple. There are so many me's within me. The whole world comes into our inner room. Visions and mysteries and secret thoughts. "How strange it all is," Dickinson must have told herself. Ý thức là nhà độc nhất mà chúng ta biết về nó

Dickinson Hai hình ảnh tới với tôi, khi nghĩ về thơ Emily Dickionson: những cái ngăn kéo, hay những chiếc hộp của người Tầu, và kịch múa rối. Hình ảnh những chiếc hộp trong những chiếc hộp liên quan tới vũ trụ học; kịch và những con rối, tâm lý học. Chúng, lẽ dĩ nhiên mắc míu ngầm với nhau. Cõi bao la ngầm, riêng tư của ý thức là mối bận tâm thường hằng của Dickinson. Tôi tưởng tượng bà ngồi hàng giờ cho đến tận cùng trong căn phòng của bà, mắt nhắm, nhìn vào bên trong mình. Có ý thức, quan tâm, quan hoài…. là đã có chia ly rã rời, đành đoạn. Là đã có rất nhiều “tôi”, trong tôi. Trọn thế giới, lọt vô căn phòng nội, riêng tư, của mỗi chúng ta. Những viễn ảnh, những bí mật, và những ý nghĩ bí mật. “Lạ làm sao, tất cả những điều đó”, tôi nghe bà tự nói, với chính bà, hẳn thế. CHINESE BOXES AND PUPPET THEATERS

Consciousness is the only home of which we know.

-DICKINSON

Two images come to mind when I think of Emily Dickinson's poems: Chinese

boxes and puppet theaters. The image of boxes inside boxes has to do with

cosmology, and theaters and puppets with psychology. They're, of course,

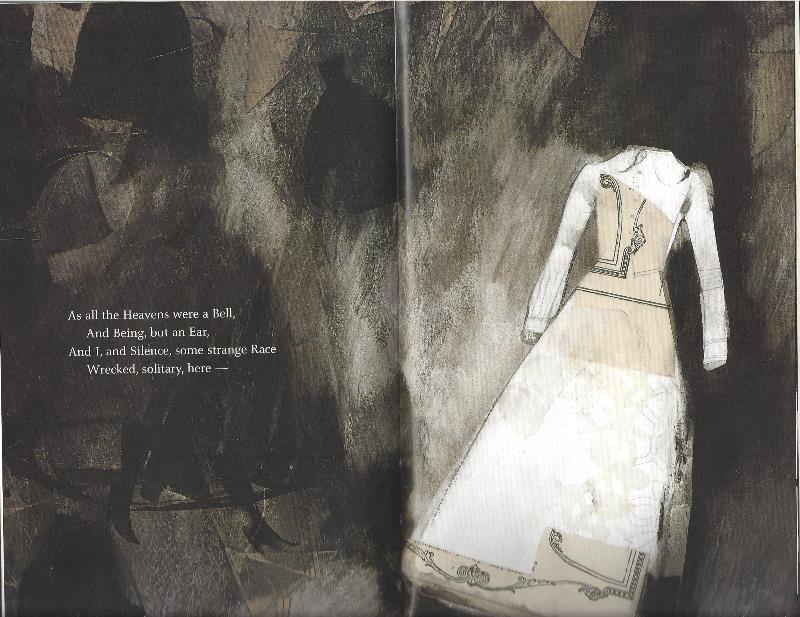

intimately related. The intimate immensity of consciousness is Dickinson's constant preoccupation. I imagine her sitting in her room for hours on end, with eyes closed, looking inward. To be conscious is already to be divided, to be multiple. There are so many me's within me. The whole world comes into our inner room. Visions and mysteries and secret thoughts. "How strange it all is," Dickinson must have told herself. Every universe is enclosed in some other universe. She opens boxes, Pandora's boxes. There's terror in one; awe and ecstasy in the next one. She cannot leave the boxes alone. Her imagination and love of truth conspire against her. There are so many boxes. Every so often, she may believe that she has reached the last one, but on closer examination it proves to contain still another box. The appearances deceive. That's the lesson. A trick is being played on her as it is being played on all of us who wish to reach the truth of things. "As above, so below," Hermes Trismegistus claimed. Emerson thought the same. He believed that clarity and heightened understanding would follow the knowledge of that primary law of our being. Dickinson's experience of the self is very different. The self for her is the place of paradoxes, oxymorons, and endless ambiguities. She welcomed everyone of them the way Emerson welcomed his clarities. "Impossibility, like wine, exhilarates," she told us. Did she believe in God? Yes and no. God is the cunning of all these boxes fitting inside each other, perhaps? More likely, God is just another box. Neither the tiniest one nor the biggest imaginable. There are boxes even God knows nothing of. In each box there's a theater. All the shadows the self casts and the World and the infinite Universe. A play is in progress, perhaps always the same play. Only the scenery and costumes differ from box to box. The puppets enact the Great Questions-or rather Dickinson allowed them to enact themselves. She sat spellbound and watched. Some theaters have a Christian setting. There is God and his Son. There is Immortality and the snake in Paradise. Heaven is like a circus in one of her poems. When the tent is gone, "miles of Stare" is what remains behind. In the meantime, the Passion and Martyrdom of Emily Dickinson go on being played under the tent and under the open skies. There's no question, as far as I am concerned, that real suffering took place among these puppets. In some other theaters the scenery could have been painted by De Chirico. In them we have a play of abstract nouns capitalized and personified against a metaphysical landscape of straight lines and vanishing points. Ciphers and Algebras stroll along "Miles and Miles of Nought" and converse. "The Truth is Bald and Cold," she says. Truth is a terrifying mannequin, as Sylvia Plath also suspected. This is the theater of metaphysical terror. Death is in all the plays and so in this woman. Death is a kind of master of ceremonies, opening boxes while concealing others in his pockets. The self is divided. Dickinson is both on stage and in the audience watching herself. "The Battle fought between Soul and No Man" is what we are all watching. That she made all this happen within the length of a lyric poem is astonishing. In Dickinson we have a short poem that builds and dismantles cosmologies. She understood that a poem and our consciousness are both a theater. Or rather, many theaters. "Who, besides myself, knows what Ariadne is," wrote Nietzsche. Emily Dickinson knew much better than he did. Charles Simic Written for an Emily Dickinson issue of the magazine Ironwood in 1986

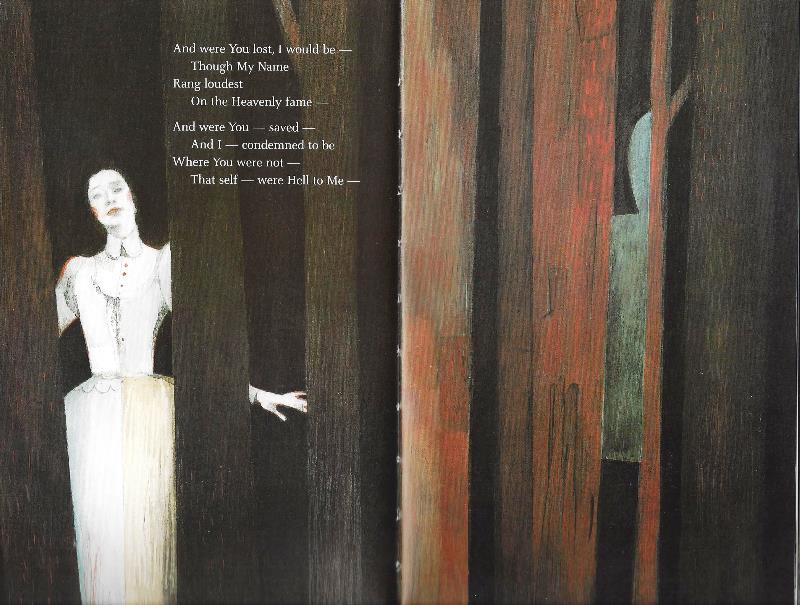

(1) So We must meet apart - You there - I - here- With just the Door ajar That Oceans are - and Prayer - And that White Sustenance- Despair – Gặp nhau ta giữ xa xa (!) Anh bên kia đứng, em qua bên này Một khung cửa hé chia hai Nguyện cầu như biển chạy dài mênh mông Nuôi nhau - Tuyệt Vọng trắng ngần (2) Because I could not stop for Death - He kindly stopped for me - The Carriage held but just Ourselves - And Immortality. Em không thể ghé thăm Thần Chết Nên dịu dàng Người đến đưa Em Cỗ xe lăn bánh êm đềm Người, và Bất Tử cùng Em lên đường Dịch tuyệt quá. Cám ơn nhiều. NQT

|

\

\