|

Note: Ông

này là 1 trong những dịch giả thơ TT, và là tác giả bài viết Translating

Tomas Tranströmer, Dịch TT Gấu tính dịch

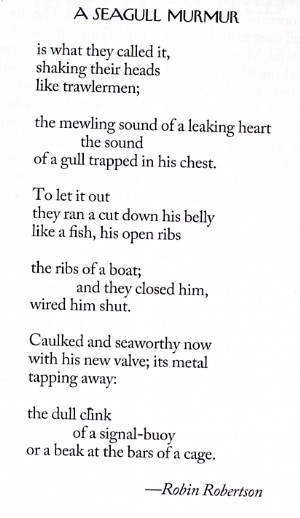

bài thơ trên, và giữ nguyên cái form của nó trên tờ báo, thay vì scan. Bài thơ của

Gấu cũng có hải âu, cũng có tiếng thì thầm của hải âu, của Gấu, và của

biển TOMAS

TRANSTROMER Here,

the

Greece of islands and ports gives occasion to Swedish poet Tomas

Transtromer for

a descriptive poem which changes into a moral parable.

SYROS In

Syros' harbor abandoned merchant ships lay idle. CAPE

RION, Monrovia. Dark

paintings on the water, they have been hung aside. Like

playthings from our childhood, grown gigantic, XELATROS,

Piraeus. But

when we first came to Syros, it was at night, Translated from the Swedish by May Swenson

and Leif Sjoberg Ở đây, Hy Lạp

của những hòn đảo và bến cảng là dịp để nhà thơ Thụy Ðiển Tomas

Transtromer SYROS Cảng Syros

hoang phế CAPE RION,

Monrovia. Những bức họa

u tối trên mặt nước, chúng được treo một bên. XELATROS,

Piraeus. Nhưng khi chúng

tôi tới Syros lần đầu thì là vào ban đêm. Trên net, tờ Người Kinh Tế có

bài viết về Nobel văn chương năm nay của Prospero. Cái

chi tiết thần kỳ mà Prospero khui ra từ thơ của Tomas Transtromer, [the

Swedish

Academy has praised an oeuvre that is “characterised by economy”], làm

GCC nhớ

tới Brodsky, qua đoạn viết sau đây: Bài

thơ đâu khác chi một giấc mơ khắc khoải,

trong đó bạn có được một cái chi cực kỳ quí giá: chỉ để mất tức thì.

Trong giấc

hoàng lương ngắn ngủi, hoặc có lẽ chính vì ngắn ngủi, cho nên những

giấc mơ như

thế có tính thuyết phục đến từng chi tiết. Một bài thơ, như định nghĩa,

cũng giới

hạn như vậy. Cả hai đều là dồn nén, chỉ khác, bài thơ, vốn là một hành

vi ý thức,

không phải sự phô diễn rông dài hoặc ẩn dụ về thực tại, nhưng nó chính

là thực

tại. Nobel prize

for literature The Swedish

poet you will soon be reading Oct 6th

2011, 18:43 AMID the

flurry of last-minute bets for Bob Dylan (once rated by bookies at

100/1), a

relatively unknown Swedish poet, Tomas Tranströmer, has won the Nobel

prize for

literature. “He is a poet but has never really been a full-time

writer,”

explained Peter Englund, the permanent secretary of the Swedish

Academy, which

decides the award. Though Mr Tranströmer has not written much lately,

since

suffering from a stroke in 1990 that left him partly paralysed, he is

beloved

in Sweden, where his name has been mentioned for the Nobel for years.

One

newspaper photographer has been standing outside his door on the day of

the

announcement for the last decade, anticipating this moment. Tomas

Tranströmer – My Nobel prize-winning hero The literature prize means the world of poetry can finally raise a glass to salute this humble man

Nguyên tác tiếng Anh: Tranströmer's

surreal explorations

of the inner world and its relation to the jagged landscape of his

native country have been translated

into over 50 languages. GCC

dịch: Những

thám hiểm siêu thực [TQ bỏ từ này] thế giới nội tại, và sự

tương quan của

nó [số ít, không phải những

tương quan] với những phong cảnh lởm chởm [TQ bỏ từ

này luôn] của quê hương của ông được dịch ra trên 50 thứ tiếng. Mấy từ quan trọng, TQ đều bỏ, chán thế. Chỉ nội 1 từ

“lởm chởm” bỏ đi, là mất mẹ 1 nửa cõi

thơ của ông này rồi. Chứng cớ: The

landscape of Tranströmer's poetry has remained constant during his

50-year

career: the jagged coastland of his native Sweden, with its dark spruce

and

pine forests, sudden light and sudden storm, restless seas and endless

winters,

is mirrored by his direct, plain-speaking style and arresting,

unforgettable

images. Sometimes referred to as a "buzzard poet", Tranströmer seems

to hang over this landscape with a gimlet eye that sees the world with

an

almost mystical precision. A view that first appeared open and

featureless now

holds an anxiety of detail; the voice that first sounded spare and

simple now

seems subtle, shrewd and thrillingly intimate. [Phong cảnh

thơ TT thì thường hằng trong 50 năm hành nghề thơ: miền đất ven biển

lởm chởm của

quê hương Thụy Ðiển với những rừng cây thông, vân sam u tối, chớp bão

bất thần,

biển không ngừng cựa quậy và những mùa đông dài lê thê, chẳng chịu chấm

dứt, phong

cảnh đó được phản chiếu vào thơ của ông, bằng 1 thứ văn phong thẳng

tuột và những

hình ảnh lôi cuốn, không thể nào quên được. Thường được nhắc tới qua

cái nick

“nhà thơ buzzard, chim ó”, Transtromer như treo lơ lửng bên trên phong

cảnh đó với con mắt gimlet [dây câu bện thép], nhìn

thế giới với 1 sự chính xác hầu như huyền bí, thần kỳ. Một cái nhìn

thoạt đầu có

vẻ phơi mở, không nét đặc biệt, và rồi thì nắm giữ một cách âu lo sao

xuyến chi

tiết sự kiện, tiếng thơ lúc đầu có vẻ thanh đạm, sơ sài, và rồi thì

thật chi li,

tế nhị, sắc sảo, và rất ư là riêng tư, thân mật đến ngỡ ngàng, đến sững

sờ, đến

nghẹt thở.] Chỉ đến khi ngộ ra cõi thơ, thì Gấu mới hiểu ra là, 1 Nobel văn chương về tay 1 nhà thơ là 1 cơ hội tuyệt vời nhất trong đời một người… mê thơ. Người ta thường

nói, thời của anh mà không đọc Dos, đọc Kafka… thí dụ, là vứt đi, nhưng

không được

nhìn thấy 1 nhà thơ được vinh danh Nobel thì quả là 1 đại bất hạnh! Thành thử, Gấu

rất bực vị sư phụ tiếng Anh của Gấu, khi bà khăng khăng không chịu dịch

thơ, không

thích đọc thơ dịch, không… thơ, tuy bà là 1 nữ thi sĩ rất ư là khiêm

nhường với

những bài thơ khiêm nhường của bà. Câu chuyện

sau đây, thật thi vị, thật tuyệt vời, và lẽ tất nhiên, vì thật thi vị,

thật tuyệt

vời cho nên, thật.. sến, và vào những ngày đầu năm, thật quá đắc địa để

mà kể

ra, bởi vì nó đẹp như là những lời chúc mừng ngày đầu năm vậy. Thơ, ngôn ngữ của đam mê? The

literature prize means the world of poetry can finally raise a glass to

salute this

humble man: Tuyệt. "No

poet expresses better the relationship between humans and the natural

world.

The black and melancholy seas, the drifting seagulls, the oaks and

elks, the

storms, rowanberries, the moon and stars, the well, salt, and wolves

are agents

rather than background; they are what the world is, as much as we are.

It's

dark, and thoughtful. It is, also, bleakly intelligent."

TOMAS

TRANSTROMER Here, the

Greece of islands and ports gives occasion to Swedish poet Tomas

Transtromer SYROS In Syros'

harbor abandoned merchant ships lay idle. CAPE RION,

Monrovia. Dark

paintings on the water, they have been hung aside. Like

playthings from our childhood, grown gigantic, XELATROS,

Piraeus. But when we

first came to Syros, it was at night, Translated

from the Swedish by May Swenson and Leif TOMAS TRANSTROMER A

transformation of the landscape, and awareness of the alienation of man

OUTSKIRTS Men in

overalls the same color as earth rise from a ditch. Translated

from the Swedish by Robert Bly TOMAS

TRANSTROMER 1931- This poem by

Transtromer is the most literally spoken in the now, and it's so

impressive

that we forget to ask when-how long ago-the observer lived through it.

It's

like a snapshot, though enriched by things known from the past, in a

dream or

during illness. TRACKS Night, two

o'clock: moonlight. The train has stopped As when

someone has gone into a dream so far And as when

someone goes into a sickness so deep The train

stands perfectly still. Translated

from tire Swedish by Robert Bly

A poem by

the 2011 Nobel prize for literature winner One evening

in February I came near to dying here. My name, my

girls, my job The approaching

traffic had huge lights You could

almost pause Then

something caught: a helping grain of sand Then –

stillness. I sat back in my seat-belt II I have been

walking for a long time In other

parts of the world To be always

visible – to live The

murmuring rises and falls Everyone is queuing at everyone's door. Many. One. |