Dịch thuật | Dịch ngắn | Đọc sách | Độc giả sáng tác | Giới thiệu | Góc Sài gòn | Góc Hà nội | Góc Thảo Trường

Giai thoại | Potin | Linh tinh | Thống kê | Viết ngắn | Tiểu thuyết | Lướt Tin Văn Cũ | Kỷ niệm | Thời Sự Hình | Gọi Người Đã Chết

Thơ Mỗi Ngày | Chân Dung | Jennifer Video

Nhật Ký Tin Văn / Viết mỗi ngày/Sách & Báo Mới

https://www.facebook.com/quoc.t.nguyen.1

|

|

448

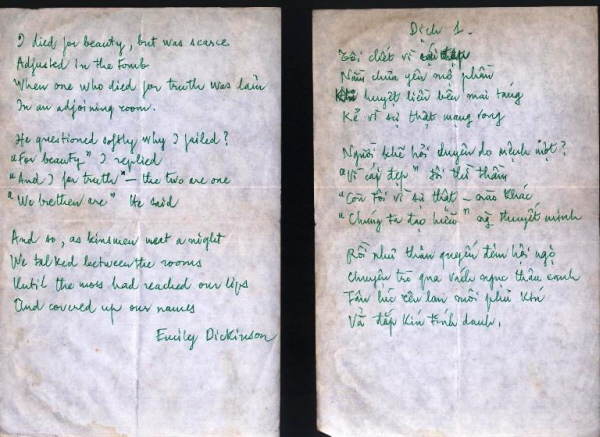

I died for Beauty - but was scarce

Adjusted in the Tomb When One who died for Truth, was lain In an adjoining Room - He questioned softly "Why I failed"? "For Beauty", I replied - "And I - for Truth - Themself are One - We Bretheren, are", He said - And so, as Kinsmen, met a Night – We talked between the Rooms – Until the Moss had reached our lips - And covered up - Our names - This little fable, stemming ultimately from the motto "Beauty is Truth, Truth Beauty" spoken by Keats's Urn, is one of many poetic attempts to reconcile the Good, the True, and the Beautiful (traditionally known as the "Platonic Triad"). Perhaps no poet has been able to give equal weight to all three concerns. Keats himself was in fact beginning to put new emphasis on the Good in his last works, but he had spent most of his short life thinking about the relation of Beauty (aesthetic creation and its product) to Truth (both philosophical and representational). Dickinson resolves the old quarrel between the truth of Beauty and the truth of Reason by letting Reason deny the existence of the quarrel: '''We Bretheren, are; He said - ". How is it that these "Bretheren," if they are indeed brothers, have never met until the grave unites them? Dickinson allows the person who died for Beauty, who is the "lead speaker" of the poem, to revise the relationship a little: they are "Kinsmen,” but have strayed into a shared domain only now. "Truth" is male in this narrative, as the pronouns tell us; it seems probable that Dickinson intend "Beauty" to be female. Each a hemisphere, together they make a whole. Why have Truth and Beauty died? Truth puts the question first, to Beauty: "Why did you fail?" (in the sense of "weaken and die"). "For Beauty:' she replies. "And I - for Truth:' he says, but continues with his declaration of their intimate relationship (as though Beauty would not know, unless he told her, that Truth is her Brother). Beauty had apparently never thought about her relation to Truth; she was self-sufficient. But Truth had thought about his relation to Beauty-he had ascertained what his complement must be. This interesting asymmetry has separated them until now; but Truth has convinced Beauty that a near-relation of hers, a Kinsman, lies in the Room adjoining hers in the Tomb. Dickinson will not attempt a complete fusion. A wall separates Beauty from Truth, and it does not disappear. When we use an expression such as "He died for God and Country,' we envisage a battle; when we say, "She died for her faith:' we envisage a martyrdom. Apparently, Beauty and Truth have died in affirmation of the values they endorse; society will not permit their continued existence. Yet there is no recrimination in these two who have been so steadfast, nor any indictment of the values opposed to their own. They were not executed; they merely "died" or "failed" for Beauty or Truth. The idiom "I died [failed] for Beauty" substitutes a weak verb of nonaction for a strong verb of action, as in “I fought for Beauty" or "I spoke for Beauty." In the Tomb, the adversary no longer matters; to "fail" in the service of a cause places agency within the self, rather than in the hands of an enemy ("I was martyred for Beauty"). In any case, what seems to be-astonishingly-the first mutual recognition of Truth and Beauty softens the impact of the grave, to which Beauty is “scarce/Adjusted" (as though it were a new climate). She is "Adjusted"; he is “adjoining": Dickinson's graphic and phonetic "matches" confirm the relationship of the two ideals. Beauty's "Tomb" matches Truth's "Room." They are Kinsmen indeed. Their warm talk continues, until-in one of Dickinson’s startling flashes of metaphor-they metamorphose into their own Tombstones. Eventually, but mercifully only after some time, the moss on the stone will grow high enough to obliterate the names of these Kinsmen, as, in a second flash-forward to the future, the lips that were enabling speech in the Tomb fall silent when the moss covers their names. It is not the attrition of the time and weather that obliterates the names, as it would be in an ordinary cemetery; rather, in Dickinson's gentle close, it is the beneficent green of nature that eventually resolves all distinctions. As "Tomb" rhymed with "Room" in the first instance, now "Rooms" rhymes with "names" as even the highest Platonic concepts gradually disappear under the Moss. The simplicity of both fable and diction has made "I died for Beauty - "none of Dickinson's best-known poems, but under the simplicity lies a real inquiry into the relations of Truth and Beauty. The fact remains that they can never occupy the same room, however much their lips can express kinship in words. Helen Vendler: Dickinson, Selected Poems and Commentaries Đọc cái còm của nữ phê bình gia Thụy Khuê-Yankee mũi lõ, thì hoá ra là, bài thơ này, “mắc mớ” tới bài thơ Phượng Hoàng & Bồ Câu, của Shakespeare, TTT dùng làm đề từ cho Một Chủ Nhật Khác, và xoay quanh thứ tình yêu “Chiêm Ngưỡng & Kính Trọng”, tức tam giác tình lý tưởng, the Platonic-triad, mà em BHD đã từng phán, thứ tình yêu đó cũng làm Hương... sợ! Nếu như thế, TTT, đọc/dịch Dickinson, và hiểu, bài thơ, đúng như Vendler cắt nghĩa? Thảo nào BHD…. sợ! Phượng Hoàng và Bồ Câu

Cái đẹp, sự thật, sự hiếm quí Ân sủng rất mực giản dị Táng tro cốt nơi đây. Cõi chết Phượng Hoàng nương náu Và ngực Bồ Câu đoan trinh Trong thiên thu an nghỉ. Không lưu truyền tông tích Chẳng bởi tật nguyền Vì chưng hôn phối thanh khiết. Vẻ thật không sao thật Dáng đẹp phô, hão huyền Sự thật cùng cái đẹp đã mai một. Trước quanh quách đôi linh điểu Hằng chân thật hoặc mỹ miều Vọng gửi khúc kinh cầu ngưỡng mộ. Thanh Tâm Tuyền dịch The Phoenix and the Turtle

Beauty, truth, and rarity, Grace in all simplicity, Here enclosed'd in cinders lie Death is now the phoenix' nest, And the turtle's royal breast To eternity cloth rest, Leaving no posterity - "Twas not their infirmity, It was married chastity. Truth may seem but cannot be; Beauty brag, but 'tis not she; truth and beauty buried be. To this urn let those repair That are either true or fair; For those dead birds sigh a prayer. William Shakespeare Tứ tấu khúc

Tình yêu, tình yêu, anh mơ tưởng hạnh phúc còn em nghĩ hạnh phúc không có, "Je t’aime parce que tu veux l’impossible", và chàng trả lời, "Muốn hưởng hạnh phúc thì ít nhất phải tin hạnh phúc có." Nhưng hạnh phúc ở đâu, ở trên trời, hay ở dưới đất, hay ở địa ngục? Chúng tôi sẽ phải làm một điều thiện vĩ đại để có vé vào thiên đàng, hay một điều ác thật ghê rợn, để chiếm lấy địa ngục, cho chỉ hai đứa? (Thứ tình yêu chỉ gồm có chiêm ngưỡng và kính trọng, thứ amour platonique mà anh nói đó cũng làm Hương sợ). BHD không nhắc tới ngôi mộ, nhưng mà là địa ngục, còn khủng hơn cả Dickinson! The Phoenix And The Turtle poem by Shakespeare is perhaps his most obscure work, verging on the metaphysical as an allegorical poem about the death of a perfect love. The Phoenix And The Turtle was published untitled in 1601 as one of the Poetical Essays appended to Robert Chester’s ‘Love’s Martyr’. http://www.nosweatshakespeare.com/shakespeares-poems/the-phoenix-and-the-turtle/ Phượng Hoàng & Bồ Câu là 1 bài thơ cực kỳ u tối, khó hiểu. Chúng ta tự hỏi, tại làm sao TTT lại dùng nó làm đề từ cho cuốn tiểu thuyết? Bây giờ, lại thêm 1 cú bí hiểm thứ nhì, là bài thơ dịch Dickinson. Tin Văn sẽ đi 1 đường tiếng Mít, và sau đó, độc giả tùy nghi.... Bài ngụ ngôn nho nhỏ, bắt nguồn từ “Cái Đẹp là Sự Thực, Sự Thực Cái Đẹp” của Keats’s Urn, là 1 trong nhiều toan tính thi ca nhằm hòa giải Cái Tốt, Cái Thực và Cái Đẹp - hiểu theo truyền thống như là tam giác [tình] lý tưởng. Có lẽ chưa có ai đem đến một sức nặng đồng đều cho cả ba. Keats, chính ông, thực ra đã bắt đầu coi trọng Cái Tốt, trong những tác phẩm sau cùng, nhưng ông trải qua hầu hết cuộc đời ngắn ngủi để suy tư về liên hệ của Cái Đẹp (sáng tạo mỹ học và những sản phẩm của nó) với Sự Thực (cả về triết lý lẫn trình diễn). Dickinson giải quyết cuộc lèm bèm cũ rích này, về sự thực của Cái Đẹp và sự thực của Lý Lẽ, bằng cách, để Lý Lẽ chối bỏ sự hiện hữu của 1 cuộc lầu bầu như thế, Chúng ta là bằng hữu, là bạn quí, là tín hữu, là… Anh ta phán. Bạn quí như thế nào, gặp nhau ở đâu (chắc ở Quán Chùa, “Chúa Ơi!”- thuổng NDT), cho đến khi nấm mồ kết nối họ. Dickenson để cho nhân vật chết vì Cái Đẹp, làm phát ngôn viên dẫn đạo của bài thơ, xì ra tí ti, về liên hệ, chúng là là đạo hữu, bị nhốt chung vào 1 nấm mồ. “Sự Thực” là “đực”, trong dòng kể, như đại danh từ “he” cho thấy. Nếu như thế, thì có thể, Dickinson coi “Cái Đẹp” là “cái”. Mỗi bên nửa trái cầu, cùng nhau, họ làm thành trọn ổ. [Trong MCNK, nhân vật Hiền sau cùng biến mất, và Duy, có lần tính hỏi Kiệt, Hiền đâu rồi. Khi dịch bài thơ của Dickinson, có thể TTT nhắm trả lời Duy, Hiền ở chỗ đó đó, chỗ mà Kiệt đưa cô tới, rồi trở về với vợ con. Và cái truyền thuyết về 1 miền đã mất, sản sinh ra những tác phẩm như Anh Môn, Gatsby, MCNK, sau cùng, do Dickinson trả lời: Nấm Mồ.] Marina

Tsvetaeva

12.

One great poet of her generation Tsvetaeva did meet; in 1916, she met young Osip Mandelstam. They had a brief affair during the Civil War. Mandelstam visited her so often-by train from St. Petersburg-that one friend joked, "I wonder if he is working for the railways." Years later, Nadezhda Mandelstam, the poet's widow, recalled: The friendship with Tsvetaeva, in my opinion, played an enormous role for Mandelstam 's work. It was a bridge on which he walked from one period of his work to another. With poems to Tsvetaeva begins his second book of poems, Tristia. Mandelstam's first book, Stone, was the restrained, elegant work of a Petersburg poet. Tsvetaeva's friendship gave him her Moscow, lifting the spell of Petersburg's elegance. It was a magical gift, because with Petersburg alone, without Moscow, there is no freedom of full breath, no true feeling of Russia, no conscience. I am sure that my own relationship with Mandelstam would not have been the same if on his path he had not met, so bright and wild, Marina. She opened in him the love of life, the ability for spontaneous and unbridled love of life, which struck me from the first minute I saw him. According to Mme. Mandelstam, "Tsvetaeva had a generosity of soul and a selflessness which had no equal. It was directed by her willfulness and impetuosity, which too, had no equal." 13. A fact: the Revolution brought Tsvetaeva poverty and the five-year-long absence of her husband, who joined the White Army and fought the Revolutionaries in Crimea and elsewhere. A fact: after the Revolution, Tsvetaeva almost starved. She left both of her daughters in an orphanage where it was said they would be better fed, and one of them, the younger, Irina, died of starvation. When my child died in Russia from hunger and I learnt of this- simply on the street from a strange person-("Little Irina your daughter?- Yes-She died. Yesterday died. Tomorrow we will bury her.")-and I kept silent three months-not a word of death-to anyone-so she [the child] did not die finally, and still (in me)- lived. This is why your Rilke did not mention my name. To name [call/speak] -is to take apart: to separate self from thing. I don't name anyone-ever. This too, is a lesson found in her poetics: Marina Tsvetaeva, the poet so obsessed with the Russian language, the Russian poet of her generation, the poet who wrote elegies for everyone else-including the living-at her own elegiac moment, chose not to speak. 12 Một nhà thơ lớn của thời của bà, Tsvetaeva đã từng gặp; vào năm 1916, bà gặp Osip Mandelstam trẻ. Họ có 1 cuộc tình ngắn ngủi trong thời kỳ Nội Chiến. Mandelstam thường xuyên thăm bà - bằng hoả xa từ St. Petersburg – một người bạn thân nói đùa, hay là anh ta là nhân viên hỏa xa. Những năm sau đó, bà vợ góa của Mandelstam nhớ lại: Tình bạn với Tsvetaeva theo tôi, đã ảnh hưởng lớn lên thơ của Mandelstam. Nó là cây cầu mà nhờ nó mà nhà thơ bước từ một giai đoạn của mình, qua 1 giai đoạn khác. Với những bài thơ với Tsvetaeva, bắt đầu cuốn thơ thứ nhì của anh, Tristia. Tập thơ đầu, Stone, là 1 tác phẩm câu thúc, thanh nhã, của nhà thơ của St. Petersbug. Tình bạn với Tsvetaeva cho anh, Moscow của bà, thoát ra khỏi lời nguyền của sự lịch lãm của St. Petersburg. Đúng là 1 món quà thần kỳ, bởi là vì với chỉ Petersburg không thôi, không có Moscow, thì sẽ thiếu khí trời, thiếu sự tự do của hơi thở trọn vẹn, đếch có tình tự thực, cảm nghĩ thực, về Nga xô, đếch có luôn lương tâm, ý thức… Ui chao, đọc, thì lại nghĩ đến Gấu Cà Chớn: Giả như đếch có Xề Gòn? Phan Thiền Sư & kiêm nhà báo, nhận ra điều này, khi viết về GCC: Tác giả Nguyễn Quốc Trụ đã nổi tiếng từ thập niên 1960s tại Sài Gòn, với các thể loại truyện ngắn, tạp ghi và biên khảo văn học. Ra hải ngoại, ông viết bài cho nhiều báo, chuyên khảo về văn học Việt Nam và thế giới, đang thực hiện trang web riêng ở địa chỉ tanvien.net. Với ngôn ngữ rất là Bắc Kỳ, và gần suốt một đời trưởng thành và sống tại Miền Nam, văn của NQT đã trở nên đa dạng và phức tạp hơn hầu hết những người cầm bút cùng thời. Penguin

Russian

Poetry

Akhmatova: Nửa Thế Kỷ Của Tôi

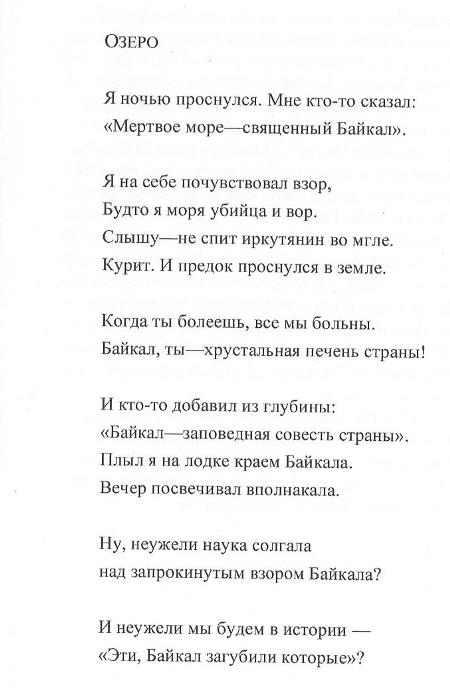

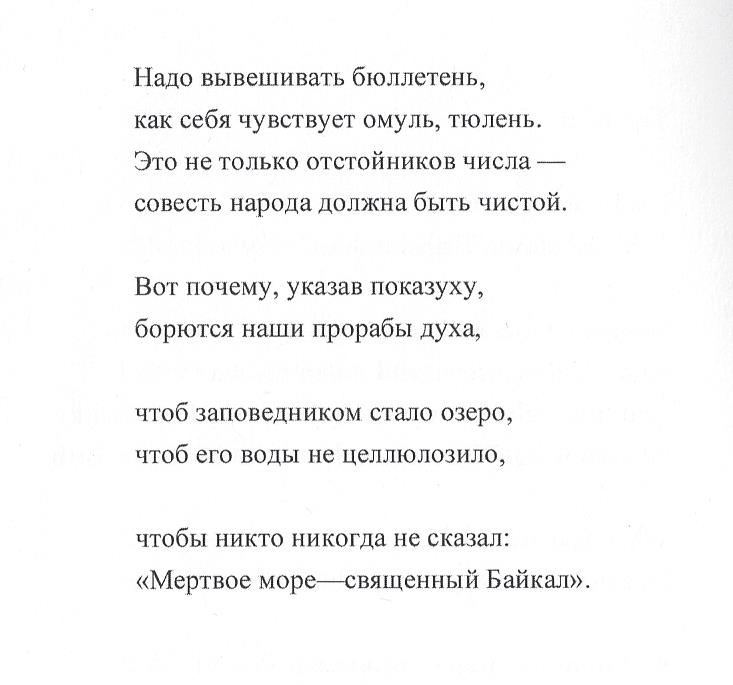

The lake I woke at night. Some said: "The sea of holy Baikal is dead." Someone's eyes are on me. As if I had murdered and stolen the sea. And hear-the Irkutskian is wide awake in the dark. He's smoking. The ancestor has wakened in the earth. When you are sick, we are sick. Baikal, the country's crystal liver! And from the deep someone added: "Baikal, the inner eye of our world." I drifted in a boat along the Baikal shore. Evening had a lustre. So, did science actually tell lies Before the unflinching eye of Baikal? And will we really be known as- "Those who wrecked Baikal"? We must send out a bulletin, About how salmon and seal feel. It's not only the increasing sediment- The country's conscience has got to be cleared. This is why, as they ferret out the flim-flam, Dancers expert in diatribe vs dialogue wrestle To preserve the lake as a reserve, So its waters won't turn to cellulose, So no one will ever say: "The sea of holy Baikal is comatose." 30.4.2016

GCC có gần như tất cả

sách của David Remnick, nhưng thiếu cuốn đầu, tức cuốn

trên, Ngôi Mộ Lenin, Những ngày

sau cùng của Đế Quốc Xô Viết Hà, hà! … 10-5-2005 Đoạn mở ra bài Tựa, cũng thú PREFACE Long before anyone had a reason

to predict the declide and fall of the Soviet Union, Nadezhda

Mandelstam filled her notebooks with the accents of hope. She was

neither sentimental nor naive. She had seen her husband, the great

poet Osip Mandelstam, swept off to the camps during the terror of

the 1930s; she described in ruthlessly clear terms how the regime

left its subjects in a permanent state of fear. The people of the

Soviet Union had been made, as she put it, "slightly unbalanced mentally-not

exactly ill, but not normal either." But Mandelstam, unlike so many

scholars and politicians, saw the signs of the Soviet system's inherent

weakness and believed in the resiliency of the people. Trước rất lâu bất cứ một

ai có thể tin rằng, Đế Quốc Đỏ sẽ sụm, Nadezhda Mandelstam

đã viết Sổ Ghi bằng 1 thứ âm thanh của hy vọng. Bà

không phải thứ người tình cảm, hay ngây thơ,

ngù ngờ. Bà đã chứng kiến chồng mình,

nhà thơ vĩ đại Osip Mandelstam, chết trong tù thập niên

1930, thời kỳ khủng bố. Bà đã mô tả, bằng 1 giọng

cực rõ ràng, không chút thương xót,

nhà nước đối xử với nhân dân của nó, như thế

nào: bằng cách đẩy tất cả vào tình trạng

lo sợ, rằng tai họa sẽ giáng xuống bất cứ lúc nào.

Người dân Xô Viết, bà viết, thì được làm

ra, “hơi mất thăng bằng về tâm thần 1 tị - không hẳn là

bịnh, nhưng cũng không thể nói, là những con người

bình thường”. Nhưng, Mandelstam, không như những nhà

học giả hay chính trị gia, nhìn ra những dấu hiệu của sự

yếu đuối nội tại, cố hữu, gắn liền với chế độ, của hệ thống Xô Viết,

và tin tưởng ở khả năng dẻo dai, sức bật, sự phục hồi mau lẹ của

dân chúng. Bài ngắn, TV sẽ post và

dịch. PREFACE

Long before anyone had a reason

to predict the decline and fall of the Soviet Union, Nadezhda Mandelstam

filled her notebooks with the accents of hope. She was neither sentimental

nor naive. She had seen her husband, the great poet Osip Mandelstam,

swept off to the camps during the terror of the 1930s; she described

in ruthlessly clear terms how the regime left its subjects in a permanent

state of fear. The people of the Soviet Union had been made, as she put

it, "slightly unbalanced mentally-not exactly ill, but not normal either."

But Mandelstam, unlike so many scholars and politicians, saw the signs

of the Soviet system's inherent weakness and believed in the resiliency

of the people. On August 20, 1991, a rainy, miserable afternoon, I walked among the crowds protecting the Russian parliament from a potential invasion by the leaders of a military coup. We all saw that day what so few could have predicted: Soviet citizens-workers, teachers, hustlers, children, mothers, grandparents, even soldiers-all standing up to a group of ignorant men who believed themselves yet another improved version of the Bolshevik regime and possessed of a power to freeze, even turn back, time. In their hurried calculations, the conspirators assumed "the masses" were too exhausted and indifferent to fight back. But tens of thousands of ordinary Muscovites were ready to die for democratic principles. It was said then and is said even now that the Russians know little or nothing of civil society. How strange, then, that so many were willing to give up their lives to defend it. I do not usually have a great memory for the things I have read, but that afternoon of the coup, hours before it came clear that there would be no attack and the putsch would fail, I thought of a short passage, bracketed in black, in my paperback copy of Nadezhda Mandelstam's Hope Against Hope: "This terror could return, but it would mean sending several million people to the camps. If this were to happen now, they would all scream-and so would their families, friends and neighbors. This is something to be reckoned with." The leaders of the August coup had not reckoned with the development of their own people. They understood nothing. They were jailed for the miscalculation, and the struts of the old regime collapsed. ******

As I write, the euphoria of

those August days is past and Russian democracy is a delicate thing.

There are days when it seems that little has changed, that the fate

of Russia hinges, once more, on the skills, inclinations, and heartbeat

of one man. This time it is Boris Yeltsin: heroic during the coup,

flexible, clever, but also, at times, reckless with language, careless

with the bottle. No one knows what would happen should Yeltsin fall

from power, the result of a stroke or an uprising of the hardline nationalists,

neofacists, and nostalgic Communists who dominate parliament. As this

book goes to press in April 1993, the power struggle between Yeltsin

and parliament is unresolved and has underscored the lack of a clear and

workable constitution, legal system, and system of authority. The institutions

of this new society are embryonic, infinitely fragile. In January 1993, Yeltsin's program of economic shock therapy has resulted in only fitful progress, much pain, and, everywhere, anxiety. Food and other supplies are in some places more plentiful, but prices are out of control. The inflation rate is beginning to look Latin American. The heads of the vast military plants show little interest in converting to a peacetime economy, and the absurd subsidies they receive make a mess of Russia's finances. A brash new class of young hustlers and even some honest businesspeople are thriving, but the old, the weak, and the poor are despondent. The crime rate is out of control. And everywhere there is a new demagogue-Communist, nationalist, or simply mad-ready to exploit the failures, vanities, and misfortunes of the elected government. The danger of the authoritarian temptation still lurks in Russia. So far, nearly all the potential successors to Yeltsin promise to be less inclined to radical economic reform and more likely to carry out an aggressive anti-Western foreign policy. Elsewhere in the former Soviet Union, the situation is at least as worrisome. There are unlovely little wars in the Caucasus, coups d'état in Central Asia. Moldova, Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania charge Russia with imperialism for leaving behind its troops. The Russians, for their part, complain that the leaders of the Baltic governments treat non-Baits as second-class citizens. Armenia is broke and on the edge of breakdown, Georgia is consumed in civil war. Despite a series of historic treaties with the United States, the unresolved conflicts over arms stockpiles between Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan trouble our sleep with dreams of what James Baker once called "Yugoslavia with nukes." Despite it all, I am partial to Mandelstam's brand of hardheaded optimism. This book, after all, chronicles the last days of one of the cruelest regimes in human history. And having lived through those final days, having lived in Moscow and traveled throughout the republics of the last empire, I am convinced that for all the difficulties ahead, there will be no return to the past. In the West, we cannot afford to look away from this process. To refuse help will endanger Russia, the former Soviet Union, and the security of the globe. It will take many books and records to understand the history of the Soviet Union and its final collapse. We are, after all, still debating the events of 1917. To write history takes time. When asked what he thought of the French Revolution, Zhou Enlai said, "It's too soon to tell." To understand the Gorbachev period will require a new library covering an immense range of subjects: U.S.-Soviet relations, economic history, the uprisings in the Baltic states, the Caucasus, Ukraine, and Central Asia, the "prehistory" of perestroika, the psychological and sociological effects of a long-standing totalitarian regime. I went to Moscow in January 1988 as a reporter for The Washington Post and saw the revolution from that peculiar angle. Like a lot of reporters in Moscow, I was filing three and four hundred stories a year to editors who would certainly have taken more. Even then, in the midst of that feverish work, it seemed that the multiple events of the Gorbachev-Sakharov- Yeltsin era followed a certain logic, a pattern: once the regime eased up enough to permit a full-scale examination of the Soviet past, radical change was inevitable. Once the System showed itself for what it was and had been, it was doomed. I begin in Part I with that essential moment-the return of history in the Soviet Union-and then move on in Part II to the beginnings of democracy and in Part III to the confrontation between the old regime and the new political forces. Part IV is an attempt to describe, from multiple points of view, the August putsch-that most bizarre and climactic of episodes-and its aftermath. In Part V, we see the final attempt of the Communist Party to justify itself while, all around, a new country is being born. Throughout, I tell the story largely through the eyes of a few representative men and women, some well known, others not. I am sure if Nadezhda Mandelstam were alive today she would not dwell long on celebration. She would be ruthlessly critical of the inequities and absurdities of politics in post-totalitarian Russia. She would warn of the problem of expecting an injured and isolated people to make a rapid transfer to a way of life that no longer promises cradle-to-grave paternalism. She would, despite her own love of Agatha Christie novels, warn against the new tide of junk culture-the sudden infatuation with Mexican soap operas and American sneakers. She would not ignore the difficulties, even disasters, ahead. But she would, I think, remain optimistic. Optimism is a belief in a gradual and painful rise from the wreckage of Communism, a confidence that the former subjects of the Soviet experiment are too historically experienced to return to dictatorship and isolation. Already there are signs all over Russia and the rest of the former Soviet Union of new generations of artists, teachers, businesspeople, even politicians on the rise. People "free of the old complexes," as Russians say. A day may even come soon when getting from one day to the next in Russia will no longer require the sort of miracles we witnessed in the last several years of the old regime. Perhaps one day Russia might even become somehow ordinary, a country of problems rather than catastrophes, a place that develops rather than explodes. That would be something to see. Is That Kafka? Sách Báo Kẻ Phản Thùng Viết Cửu Long cuộn dòng biển Đông

dậy sóng (kỳ 1)

http://vanviet.info/van/cuu-long-cuon-dng-bien-dng-day-sng-ky-1/ Note: Cái tít, như GCC vẫn biết, thì là CL cạn dòng. Không hiểu tác giả hay VV đổi ? Cuộn, lộn, cạn, mỗi từ ý 1 khác. My Old Saigon

Bà Tám liked this.Washington Post, một tờ báo lớn ở Mỹ vừa có bài dưới đây. "OBAMA PHẢI NÓI GÌ Ở VIỆT NAM?". Xin mời bà con xem bản dịch của FB Anh Hào Phạm: (Đây là 1 dạng xã luận của báo WP): "Tổng thống Obama sẽ viếng thăm Việt Nam trong tháng này, và đây là chuyến thăm lần thứ ba của các tổng thống Mỹ đến đây kể từ khi cuộc chiến Việt Nam kết thúc cách đây hơn bốn mươi năm. ...Continue Reading

During his visit, the president should

speak out against its leaders’ abysmal human rights record.

www.washingtonpost.com|By Washington

Post Opinions, Outlook, and PostEverything

Giữa

lúc các mối quan tâm giữa hai bên về giao

thương và an ninh ngày càng được cũng cố, TT.

Obama cần phải tập trung vào thành tích nhân

quyền không mấy sáng sủa của quốc gia này.

Câu tiếng Anh, bảnh hơn nhiều, nó phán rằng, Ô Bá Mà phải chửi thẳng vào mặt VC về cái hố thẳm - chôm chữ của PCT - về thành tích về nhân quyền của chúng. Chửi, là còn may. Bà DTH, khi bà tổng thống Pháp (?), đề nghị cho tị nạn, lắc đầu, tôi phải về để ị vào mặt chúng!

Tính

kiếm số Văn Học Tẩy, chưa về, đành cầm lên số này,

trong có bài về Einstein, Đức và Do Thái,

malgré lui. Bài tuyệt lắm. Có 1 chi tiết, rất

quái, là khi còn nhỏ, bố mẹ ông bèn cho ông

đi học ở 1 trường Ky Tô, mà ông là 1 tên

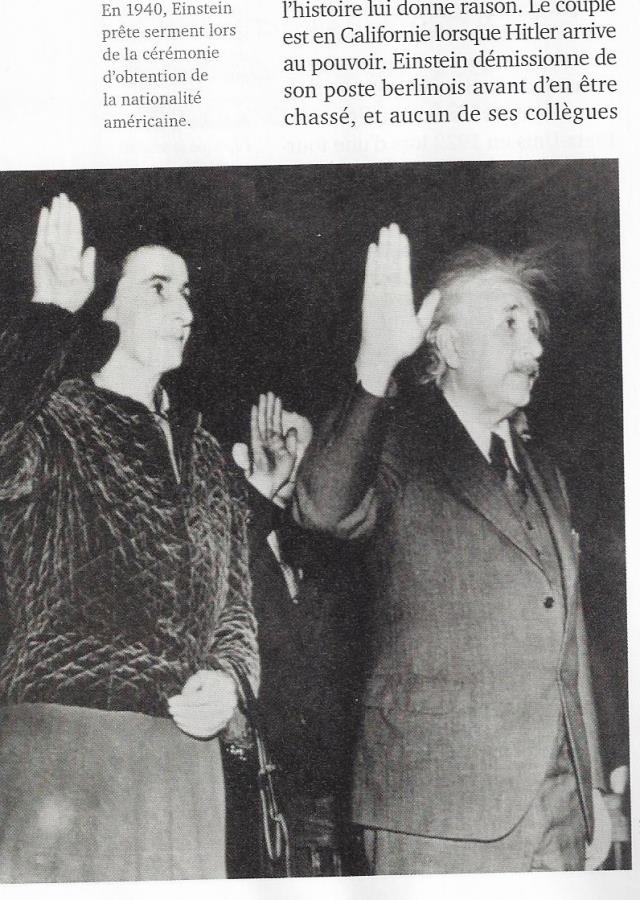

Do Thái độc nhất! Ông & bà Einstein trong lễ

tuyên thệ trở thành công dân Huê Kỳ,

1940. Solz, lắc đầu không làm công dân Mẽo,

trong khi cả gia đình OK, vì ông tin rằng, ông

sống dai hơn chế độ Xô Viết. Quả thế thực.

Số VH Tẩy mới, có bài sau đây:

Le Goncourt du premier roman refusé http://www.magazine-litteraire.com/actualite/goncourt-du-premier-roman-refuse-14-05-2016-139389 Cho Goncourt, đếch thèm nhận, mà là cuốn đầu tay! Le

Goncourt du premier roman refusé

Actualité - 14/05/2016 par Amélie Cooper (309 mots) Un inconnu, signant sous le pseudonyme de Joseph Andras, a refusé le Goncourt du premier roman pour son livre De nos frères blessés (éd. Actes Sud) qui lui a été attribué mercredi. L'Académie Goncourt avait surpris les lecteurs français en décernant à Joseph Andras son prix du premier roman : il n'apparaissait pas dans leurs sélections. L'auteur les a surpris à son tour, en ne se rendant pas au déjeuner cérémonial après la remise des prix. Puis finalement, en refusant sa récompense trois jours après l’avoir reçue. On ne sait rien de Joseph Andras, sinon qu’il vivrait en Normandie. La question brûle les lèvres de tous - et peut être était-ce le but recherché - pourquoi refuser ce prix, ainsi que la prime de 5000 euros qui l'accompagne ? Il expliquait son choix jeudi soir, dans une lettre adressée aux membres du jury Goncourt, passée par les mains de son éditrice d'Actes Sud. « La compétition, la concurrence et la rivalité sont à mes yeux des notions étrangères à l’écriture et à la création. La littérature, telle que je l’entends en tant que lecteur et, à présent, auteur, veille de près à son indépendance et chemine à distance des podiums, des honneurs et des projecteurs. Que l’on ne cherche pas à déceler la moindre arrogance ni forfanterie dans ces lignes : seulement le désir profond de s’en tenir au texte, aux mots, aux idéaux portés, à la parole occultée d’un travailleur et militant de l’égalité sociale et politique. » Joseph Andras affirme agir par conviction politique, mais cette conviction a attendu trois jours avant de s’exprimer. Il pourrait s’agir d’une stratégie de communication, mais l’hypothèse la plus probable demeure celle de son souhait de préserver son identité qu’il aurait dû divulguer s’il avait accepté le chèque de l’Académie Goncourt. À lire aussi sur La République des livres Par Amélie Cooper Ha Le liked this.Mai Thanh Hai with Trần Văn Thiệu and 8 others.KHÔNG THỂ SO SÁNH VỚI NGHỆ SĨ KIM CƯƠNG Hôm nay

commt cho bài "góc khuất của giới nghệ sĩ "thế này:"Tôi

không tin đặt tên sách "cho gió cuốn đi" thì

gió sẽ cuốn đi tất cả những cái gì đã viết

thành sách mà sách ấy đã được xuất

bản và lại được quảng bá trên vài phương tiện

truyền thông một các kéo dài.Phải chăng đây

là một điều có gì ẩn ý KHÔNG TỐT. "Trước đây cứ nghe nói đồng bào

miền Nam “bị Mỹ ngụy kìm kẹp” khổ lắm, rất cần sự giúp

đỡ từ miền Bắc, cứ hình dung dân Sài Gòn đói

khổ lắm. Mới vào Sài Gòn tôi rất ngỡ ngàng.

Chỉ cần nhìn cách ăn mặc, trang điểm, đi lại, ăn nói

nhẹ nhàng; chỉ cần ra chợ mua gì cũng có câu

cảm ơn và túi ni lông đựng đồ đủ biết mình

không cùng đẳng cấp văn minh với người ta rồi. Biết mình

bị ngộ nhận với thông tin lệch lạc."

Note: TV sorry v/v viết nhảm về Ái Vân. Sẽ delete, và thành thật xin lỗi. NQT Nếu chống cái xấu thì đảng phái cơ sở hội đoàn cá nhân nào cũng đều có thể vào cuộc!

TTO - Chiều 14-5, Công an

TP.HCM cho biết qua điều tra, thu thập thông tin đã…

tuoitre.vn|By

Tuổi

Trẻ

Biểu

tình ôn hòa, biến thành bạo động, là

do VC cố tình, để mượn cớ đàn áp.

Sẽ là đàn áp tới chỉ, vì có "dê tế thần" rồi. Đây là giờ phút quyết định. Chúng nó say giết người

như gạch ngói

Như lòng chúng ta thèm khát tương lai [Tôi gọi tên tôi cho đỡ nhớ] Thanh Tâm Tuyền Riêng với

Thanh Tâm Tuyền, bài thơ Hãy cho anh khóc bằng mắt em

Những cuộc tình duyên Hãy cho anh khóc bằng

mắt em Hãy cho anh giận bằng ngực

em Hãy cho anh la bằng cổ em Chúng nó say giết

người như gạch ngói Hãy cho anh run bằng má

em Hãy cho anh ngủ bằng trán

em Hãy cho anh chết bằng da em Những cuộc tình duyên Budapest Lê Nguyễn Hương Trà with Tâm Hoa.Cục Báo chí thuộc Bộ Thông tin & Truyền thông vừa có quyết định xử phạt vi phạm hành chính với mức 140 triệu đồng báo Nông thôn Ngày Nay về các bài viết "Mãi mãi là người đến sau" (Tuấn Khanh) và "Lời than thở của các loài cá" đăng trên ấn phẩm Thế giới Tiếp Thị của NTNN, đồng thời đòi đóng cửa vĩnh viễn ấn phẩm này. Tuy nhiên, sau đó Cục đã chấp nhận văn bản của báo Nông Thôn Ngày Nay tự đề nghị đình bản ấn phẩm TGTT ba tháng, kể từ hôm nay 14.5. Thế Giới Tiếp Thị tiền thân ... Continue Reading

Tuyên bố Vào 16g chiều ngày 14/5/2016, nhiều tờ báo của Nhà nước bất ngờ đồng loạt đưa tin "Việt Tân" là kẻ xúi giục cuộc xuống đường. Bản tin chung đưa ra mà không nói được nguyên cớ nào. Mọi thứ chỉ là một lời đe dọa vu vơ, nhưng lại chuẩn bị cho tiền đề của các trận trấn áp chà đạp lên hiến pháp. ... See More

Đúng ra, phải có 1 tên VC liều mình cứu... Quỉ Đỏ, đưa ra trình diện trước báo chi, tự nhận, tớ là Việt Tân... Trùng hợp làm sao, bài viết của David Remnick, là đúng cho ngày chủ nhật sắp sửa xẩy ra: PREFACE

Long before anyone had a reason

to predict the decline and fall of the Soviet Union, Nadezhda Mandelstam

filled her notebooks with the accents of hope. She was neither sentimental

nor naive. She had seen her husband, the great poet Osip Mandelstam,

swept off to the camps during the terror of the 1930s; she described

in ruthlessly clear terms how the regime left its subjects in a permanent

state of fear. The people of the Soviet Union had been made, as she put

it, "slightly unbalanced mentally-not exactly ill, but not normal either."

But Mandelstam, unlike so many scholars and politicians, saw the signs

of the Soviet system's inherent weakness and believed in the resiliency

of the people. On August 20, 1991, a rainy, miserable afternoon, I walked among the crowds protecting the Russian parliament from a potential invasion by the leaders of a military coup. We all saw that day what so few could have predicted: Soviet citizens-workers, teachers, hustlers, children, mothers, grandparents, even soldiers-all standing up to a group of ignorant men who believed themselves yet another improved version of the Bolshevik regime and possessed of a power to freeze, even turn back, time. In their hurried calculations, the conspirators assumed "the masses" were too exhausted and indifferent to fight back. But tens of thousands of ordinary Muscovites were ready to die for democratic principles. It was said then and is said even now that the Russians know little or nothing of civil society. How strange, then, that so many were willing to give up their lives to defend it. I do not usually have a great memory for the things I have read, but that afternoon of the coup, hours before it came clear that there would be no attack and the putsch would fail, I thought of a short passage, bracketed in black, in my paperback copy of Nadezhda Mandelstam's Hope Against Hope: "This terror could return, but it would mean sending several million people to the camps. If this were to happen now, they would all scream-and so would their families, friends and neighbors. This is something to be reckoned with." The leaders of the August coup had not reckoned with the development of their own people. They understood nothing. They were jailed for the miscalculation, and the struts of the old regime collapsed. Trước rất lâu bất cứ một ai có thể tin rằng, Đế Quốc Đỏ sẽ sụm, Nadezhda Mandelstam đã viết Sổ Ghi bằng 1 thứ âm thanh của hy vọng. Bà không phải thứ người tình cảm, hay ngây thơ, ngù ngờ. Bà đã chứng kiến chồng mình, nhà thơ vĩ đại Osip Mandelstam, chết trong tù thập niên 1930, thời kỳ khủng bố. Bà đã mô tả, bằng 1 giọng cực rõ ràng, không chút thương xót, nhà nước đối xử với nhân dân của nó, như thế nào: bằng cách đẩy tất cả vào tình trạng lo sợ, rằng tai họa sẽ giáng xuống bất cứ lúc nào. Người dân Xô Viết, bà viết, thì được làm ra, “hơi mất thăng bằng về tâm thần 1 tị - không hẳn là bịnh, nhưng cũng không thể nói, là những con người bình thường”. Nhưng, Mandelstam, không như những nhà học giả hay chính trị gia, nhìn ra những dấu hiệu của sự yếu đuối nội tại, cố hữu, gắn liền với chế độ, của hệ thống Xô Viết, và tin tưởng ở khả năng dẻo dai, sức bật, sự phục hồi mau lẹ của dân chúng Vào ngày 20 Tháng Tám, 1991, một buổi chiều mưa, thê thảm, tệ hại, tôi đi bộ giữa những đám đông bảo vệ nghị viện Nga, trước những đầu lĩnh hăm he xâm chiếm, nhằm thực hiện 1 cú đảo chánh. Tất cả những gì mà chúng ta nhìn thấy ngày hôm đó, ít người có thể tiên đoán ra được: công dân Xô viết - thợ thuyền, thầy giáo, những con người có nghị lực, trẻ em, bà mẹ, ông nội, ông ngoại, ngay cả quân nhân - tất cả đứng sừng sững trước lũ người ngu dốt, chúng tự coi chúng là một ấn bản nghèo nàn thảm hại, khác, của 1 chế độ Bôn Xê Vích ngày nào, có quyền năng đóng băng, hoặc quá nữa, quay ngược thời gian, lịch sử. Trong những toan tính vội vã của chúng, chúng hy vọng rằng, quần chúng sẽ “lại nổi dậy”, như 1 một mùa thu năm qua, cách mạng tiến ra, như bản nhạc của phù thuỷ Phạm Duy đã từng ca ngợi, hoặc, đám đông, mệt nhoài, và dửng dung, sẽ không chống cự lại. Nhưng hàng ngàn người dân Mút Ku Vít, đều sẵn sàng để chết cho những nguyên lý dân chủ. Nó đã được nói vào lúc đó, và nó được nói tới, ngay cả bây giờ, rằng, người dân Nga biết rất ít, hoặc chẳng biết gì, về xã hội dân sự.Lạ làm sao là bao con người sẵn sàng bỏ mạng sống để bảo vệ nó. |