Dịch thuật | Dịch ngắn | Đọc sách | Độc giả sáng tác | Giới thiệu | Góc Sài gòn | Góc Hà nội | Góc Thảo Trường

Thư tín | Phỏng vấn | Phỏng vấn dởm | Phỏng vấn ngắn

Giai thoại | Potin | Linh tinh | Thống kê | Viết ngắn | Tiểu thuyết | Lướt Tin Văn Cũ | Kỷ niệm | Thời Sự Hình | Gọi Người Đã Chết

Ghi chú trong ngày | Thơ Mỗi Ngày | Nhật Ký | Chân Dung | Jennifer Video

Cali, No-2012 Bobin Ghiền TTT in Ký Ức Sơ Sài Rain Paris Review 60 năm Sổ Đọc Thảm họa dịch Nostalgie de la boue Ám ảnh phố phường Câu hỏi hắc búa Viết lại Truyện Kiều Thơ vô ngôn Hope in thin shell Nhìn lại TLVD Mit Crisis Borges by Greene NQT @ talawas Tiểu thuyết là gì? 1968-Khe Sanh Sarajevo Siege 1992 Paris tắm Mit Critic Ghiền Cô Gái Chơi Cờ Pamuk: Cơn giận dữ của những kẻ bị trầm luân Viết nhỏ by PTH Anh Môn by The Economist Cavafy by Vargas Llosa Opium-Marx 20 năm VH Miền Nam Granta Sex The Good vs The Chtistian Iceberg Gatsby Simic: What if PCT triết gia Season Elegy Truyện ngắn bất khả NHT by Nhật Tuấn Steps Lost_Intel Chia tay Youth Fleeing by Cao Hành Kiện Loneliness by CHK To Young Poets by AZ NHQ và HTXHCN Bolano: Trong Ngoặc Borges's Còm Hà Nội Gió Tạp Chí ST by CTC Graham Greene Dangerous Edge Đọc lại Agatha Christie Message to 21th Century Memory Trap How to write a sentence Bùi Ngọc Tuấn Ôi chao giọng Huế Lapham Kẻ Lạ Inner Worlds LMH case Bịp Lolita loathsome brillance Kafka Poet Once upon a sea Images Life by Simic Borges by Cioran Centaur Question by P_Levi Ars Erotica

|

Thơ Mỗi Ngày Good Friday My prattle, pride, and private prices- climbing, clinching, clocking- I might loan you a few for the evening, so you don't show up at your own crucifixion naked of all purpose. • But for God's sake, don't spill any redemption on them! They're my signature looks. Body by Envy. Make up & wardrobe provided by Avarice. Lord, if you take away my inordinate cravings, what the hell's left? Do you know how much I paid for my best rages? I want them all back if they're so To Die For. Else shred my palms, wash my face with spit, let the whip unlace my flesh and free the naked blood, let me be tumbled to immortality with the stew of flood debris that is my life. Maria Melendez Kelson * Poetry Magazine, March, 2014 * Đã xb hai tập thơ với Đại Học Arizona Press Flexible Bones (2010) và How long She’ll Last in This World (2006). Hiện dậy tại Pueblo Community College in Colorado. Số báo này, có bài viết của Slavoj Zizek, Căn nhà tra tấn thơ của ngôn ngữ, GCC tính dịch, mà “quơn” hoài. Prose from Poetry Magazine

The Poetic Torture-House of Language How poetry relates to ethnic cleansing by Slavoj Žižek http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/article/247352

http://www.tanvien.net/Tho_Poetry/Zizek_Poetic_Torture_House_of_Language.html

The Poetic

Torture-House of Language What

if, however, humans exceed animals in their

capacity for violence precisely because they speak?

Liệu con người

hung bạo hơn loài vật, là do chúng... nói? Đường ra trận

mùa này đẹp lắm Almost a century ago, referring to the rise of Nazism in Germany, Karl Kraus quipped that Germany, a country of Dichter und Denker (poets and thinkers), had become a country of Richter und Henker (judges and executioners) - perhaps such a reversal should not surprise us too much. Cách

đây hầu như cả 1 thế kỷ, nhân cái vụ vùng lên của Nazi tại Đức, Karl

Kraus bèn đi

1 cú thọc lét, rằng thì là Đức vốn là 1 nước của những thi sĩ và những

nhà tư

tưởng, nay trở thành xứ xở của ông tòa và đao phủ. Thi sĩ & Toán Sĩ & Nobel Sĩ, nay biến thành Ông Tòa [Viện Tàn Sát Nhân Dân] và Đao Phủ Thủ [Cớm VC] Sách Báo

Italo Calvino: “There were years when I went to the movies almost every day, around the time of my adolescence. Those were years in which cinema was my world.” The

cinema satisfied a need for disorientation, for shifting my attention

to another place, and I believe it’s a need that corresponds to a

primary function of integration in the world, an essential phase in any

kind of development. nybooks.com

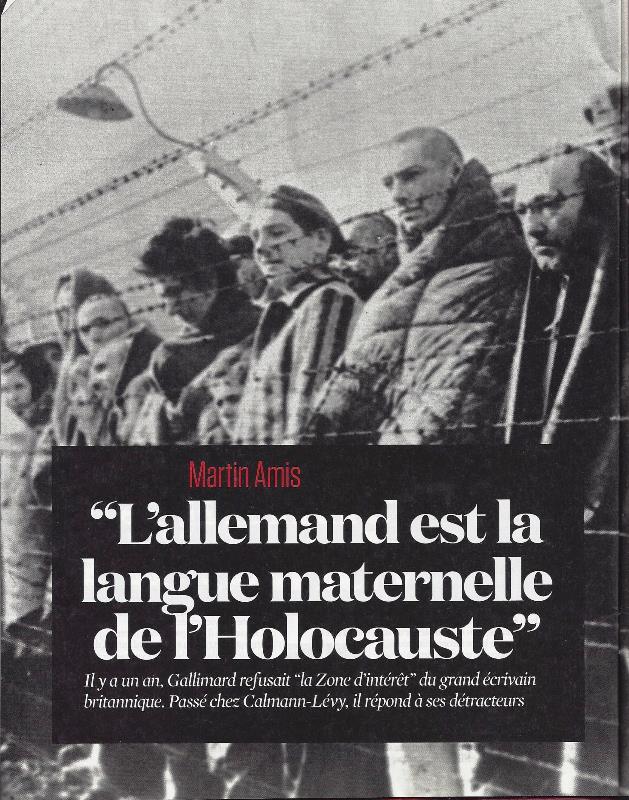

Auschwitz Tháng Tư 1942 Obs 20 & 26 Aout 2015 Tiếng Đức là tiếng mẹ đẻ của Lò Thiêu Hãy nhớ rõ 1 điều, tiếng Đức không ngây thơ vô tội trước Lò Thiêu G. Steiner: Phép Lạ Hổng Martin Amis : "L’allemand est la langue maternelle de l’Holocauste" http://bibliobs.nouvelobs.com/romans/20150818.OBS4359/martin-amis-l-allemand-est-la-langue-maternelle-de-l-holocauste.html Tại làm sao mà ông đặt tít cho cuốn sách của mình, là Miền Nhận Hàng [la Zone d’intérêt: Miền Nam nhận họ, Miền Bắc nhận hàng]?

[Note: Câu này, bản in trên báo có tí khác, bản trên net] Tôi tính gọi nó là “Tuyết màu hạt dẻ”, nhưng Simenon đã chơi cái tít “Tuyết dơ” rồi. Nabokov phán, có hai thứ tít. Thứ lòi ra sau khi viết xong, như người ta đặt tên cho đứa bé, khi nó ra đời. Thứ kia mới khủng, nó có từ trước, ngay từ đầu, nó cắm mẹ vô não của bạn từ hổi nào hồi nào. Đây là trường hợp cuốn của tôi. Vùng nhận hàng, hay, Miền Lợi Tức, là công thức mà Nazi sử dụng để chỉ Miền Lò Thiêu. Một cái tít rõ ràng ngửi ra tiền. Ui chao, thảo nào Bắc Kít gọi, Đàng Trong: Nhà của chúng. Đàng Ngoài, là, tính nhượng cho Tẫu! Amis quả đúng là 1 nhà văn xì căng đan. Cuốn sách mới xb của ông, bị Gallimard vứt vô thùng rác, dù đây là nhà xb bạn quí của ông. Cũng đếch thèm nói năng, phôn, phiếc gì hết. Rồi 1 nhà xb Đức cũng chê. Sau cùng, nhà Calmann-Lévy in nó. Theo tin hành lang, Gallimard chê, vì không tới tầm. Nhưng cuốn này, quả là khủng. Gấu mê nhất cuốn Nhà Hội của ông. Có gần đủ sách của ông, nhưng thú thực, không chịu nổi!

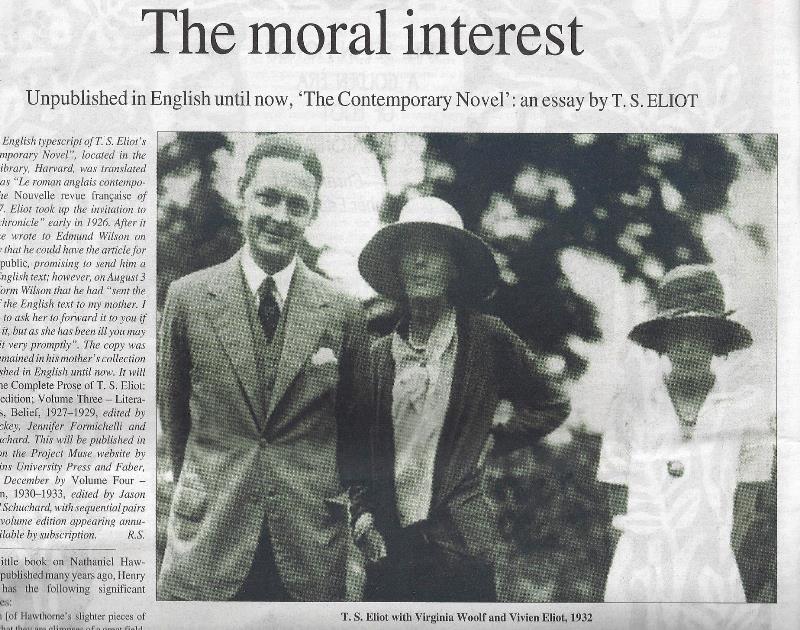

Then and Now

We look back to a review by Edgell Rickward of The Waste Land by T. S. Eliot. To read the piece in full, go to www.the-tls.co.ukTLS September 20, 1923 Eliot's gift awry Between the emotion from which a poem rises and the reader there is always a cultural layer of more or less density from which the images or characters in which it is expressed may be drawn. In the ballad" I wish I were where Helen lies" this middle ground is but faintly indicated. The ballad, we say, is simpler than the "Ode to the Nightingale"; it evokes very directly an emotional response. In the ode the emotion gains resonance from the atmosphere of legendary association through which it passes before reaching us. It cannot be called better art, but it is certainly more sophisticated and to some minds less poignant. From time to time there appear poets and a poetic audience to whom this refractory haze of allusion must be very dense; without it the meanings of the words strike them so rapidly as to be inappreciable, just as, without the air, we could not detect the vibration of light. We may remember with what elaboration Addison, among others, was obliged to undertake the defence of the old ballads before it was recognized that their bare style might be admired by gentlemen familiar with the classics. The poetic personality of Mr. Eliot is extremely sophisticated. His emotions hardly ever reach us without traversing a zig-zag of allusion. In the course of his four hundred lines he quotes from a score of authors and in three foreign languages, though his artistry has reached that point at which it knows the wisdom of sometimes concealing itself. There is in general in his work a disinclination to awake in us a direct emotional response. It is only, the reader feels, out of regard for someone else that he has been induced to mount the platform at all. From there he conducts a magic-lantern show; but being too reserved to expose in public the impressions stamped on his own soul by the journey through the Waste Land, he employs the slides made by others, indicating with a touch the difference between his reaction and theirs. So the familiar stanza of Goldsmith becomes When lovely woman stoops to folly and Paces about her room again, alone, She smoothes her hair with automatic hand, And puts a record on the gramophone. To help us to elucidate the poem Mr. Eliot has provided some notes which will be of more interest to the pedantic than the poet critic. Certainly they warn us to be prepared to recognize some references to vegetation ceremonies. This is the cultural or middle layer, which, whilst it helps us to perceive underlying emotion, is of no poetic value itself. We desire to touch the inspiration itself, and if the apparatus of reserve is too strongly constructed, it will defeat the poet’s end .... From the opening part, "The Burial of the Dead," to the final one we seem to see a world, or a mind, in disaster and mocking despair. We are aware of the toppling of aspirations, the swift disintegration of accepter stability, the crash of an ideal. Set at a distance by a poetic method which is reticence itself, we can only judge of the strength of emotion by the visible violence of the reaction. Here is Mr. Eliot, a dandy of the choicest phrase, permitting himself blatancies like “the young man carbuncular." Here is a poet capable of a style more refined than that of any of his generation parodying without taste or skill.... Here is a writer to whom originality is almost an inspiration borrowing the greater number of his best lines, creating hardly any himself.... But it is the finest horses which have the most tender mouths, and some unsympathetic tug has sent Mr. Eliot's gift awry. When he recovers control we shall expect his poetry to have gained in variety and strength from this ambitious experiment. TLS AUGUST 14 2015 Note: Bài essay, in lần đầu, dù từ hổi nảo hồi nào, TV đi thêm 1 khúc, TLS điểm “Hoang Địa”, từ 1923. Số này còn bài điểm cuốn tiểu sử Paz, cũng thú. Số trước, 7 August, có bài về Maya, nhà thơ khuôn mẫu của nhà nước Liên Xô. Steiner khi viết về cú tự sát của Maya, nhận xét, có thể những vị thần Đỏ làm ông thất vọng. Nhưng theo Gấu, nói theo Kundera, ông tự sát, vì thơ của ông làm nhiều người chết quá. Thi sĩ cùng ngồi ngai vàng với đao phủ mà! Un piège tendu

à la poésie

« Ce n'était pas seulement le temps de l'horreur, c'était aussi le temps du lyrisme! Le poète régnait avec le bourreau ". Đâu chỉ là thời của ghê rợn, của CCRD, của Đấu Tố, của Nhân Văn Giai Phẩm, mà còn là thời của thơ ca trữ tình, Mặt Trời Chân Lý Chói Qua Tim, Đường Ra Trận Mùa Này Đẹp Lắm. Tên HPNT này, tởm hơn Văn Cao. Văn Cao, viết “Tại Sao Tôi Viết Tiến Quân Ca”, như 1 lời sám hối, và sau TQC, bặt tiếng luôn. Đọc báo thấy tin hắn sắp ngỏm. Cũng, vừa thi sĩ vừa đao phủ. Chắc là vì thế mà nhà thơ hải ngoại NDT phải đi vội 1 bài ai điếu, trên Da Màu.

TLS, August 7, 2015 Note: Model poet. Nhà thơ khuôn mẫu.

Cái tít ở trang nhất, thú, “Mayakovsky của Xì”. Bài đọc cũng thú. Nó làm GCC nhớ đến Bùi Ngọc Tấn, đi tù vẫn không quên mang theo những vần thơ Maya, cái gì gì, Tôi sẽ giơ cao tờ chứng minh thư Đảng/Là toàn tập thơ bônsêvích tôi làm"? (CKN 2000, trang 106) Người điểm, Clare Cavanagh, dịch giả, chuyên gia thơ Ba Lan. Độc giả TV quá rành bà này. Tác giả cuốn tiểu sử mới thú. Tin Văn đã từng giới thiệu bài viết của ông, về Brosky, đi là đi luôn, đếch thèm về, Nhà thơ nổi loạn. Maya đã và vẫn luôn luôn là nhà thơ số 1, thiên bẩm của thời đại Xô Viết của chúng ta, lãnh đạm với tác phẩm và hồi ức về ông là một tội ác, Xì phán. Câu phán của Xì bắt đầu “cái chết thứ nhì” của Maya, Pạt đi 1 đường bình loạn! Tuy nhiên, không thú bằng nhận xét của Walter Benjamin về cái cú tự bắn vô đầu mình của thi sĩ khuôn mẫu của nhà nước Liên Xô: Một kẻ chết ở cái tuổi ba lăm, sẽ luôn luôn được đời nhắc tới, ở bất cứ thời điểm nào trong đời xừ lủy, bằng cái chết ở tuổi ba lăm! (1) Tuyệt! (1) Vladimir Mayakovsky "was and remains the best, most gifted poet of our Soviet epoch", Joseph Stalin proclaimed in 1935, five years after the revolutionary poet's shocking suicide. "Indifference to his works and memory", the dictator continued ominously, "is a crime." Thus began what Boris Pasternak called Mayakovsky' s "second death". A suitably sanitized, Stalinized Mayakovsky would henceforth, he lamented, be "forcibly introduced" into Russian literary diets "like potatoes under Catherine the Great". This force-feeding produced all sorts of consequences, intended or otherwise. "'A man ... who died at the age of thirty-five", Walter Benjamin famously remarked (paraphrasing Moritz Heimann), "will appear to remembrance at every point of his life as a man who dies at the age of thirty-five." "A man… who died at the age of thirty- five", Walter Benjamin famously remarked (paraphrasing Moritz Heimann), "will appear to remembrance at every point of his life as a man who dies at the age of thirty-five." A spectacularly talented avant-garde writer who sides with the revolutionary state early on, only to commit suicide at the age of thirty-six, at least partly from disillusionment with that state, similarly seems to demand that his life be read backwards. And indeed, Jangfeldt's preface ends with the bullet that penetrated Mayakovsky's heart, while simultaneously "shoot[ing] to pieces the dream of Communism and signal [ling] the beginning of the Communist nightmare of the 1930s", as Watson's less than felicitous rendering has it. Nevertheless, Jangfeldt's distinctive approach makes itself felt from the start. The book opens neither with the poet's birth nor with his death. It commemorates instead the day in July, 1915, when he first met the brilliant theoretician Osip Brik and his bohemian, irresistibly attractive wife, who became - with Osip's blessing - Mayakovsky's muse, patron and sometime lover for the next fifteen years. Osip and Lili were enthralled by his reading of the quasi-epic "A Cloud in Trousers": I don't have a single grey hair in my soul, and no senile tenderness! The might of my voice has expanded the world, and I come forth - a beautiful twenty-two-year-old ... It was "a most joyous date", Mayakovsky later recalled, and one, Jangfeldt argues, that shaped the rest of his brief life. Kẻ mạo tiếng WRONG NOTE

In the Belgian city of Bruges a few hundred years ago, a nine-year-old chorister who had sung a wrong note in a mass that was being performed before the entire royal court in the Bruges cathedral is said to have been beheaded. It seems that the queen had fainted as a result of the wrong note sung by the chorister and had remained unconscious until her death. The king is supposed to have sworn an oath that, if the queen did not come round, he would have not only the guilty chorister but all the choristers in Bruges beheaded, which he did after the queen had not come to and had died. For centuries no sung masses were to be heard in Bruges. Nốt nhạc sai

Ở thành phố Bruges, Bỉ, vài trăm năm trước đây, một bé gái 9 tuổi, trong giàn thánh ca nhà thờ, trong một thánh lễ, trước hoàng gia, đã bị chặt đầu, do hát sai một nốt nhạc. Nốt nhạc sai của cô bé khiến hoàng hậu giật mình, rồi hôn mê, rồi chết. Theo kể lại, vị hoàng đế thề rằng, nếu hoàng hậu không tỉnh lại, thì, không chỉ cô bé gái, mà tất cả giàn thánh ca đều bị chặt đầu, và chuyện đã xẩy ra đúng như thế. Bởi thế mà hàng thế kỷ sau đó, thành phố này không có thánh ca.

Viết Mỗi Ngày

manhhai SAIGON 1969 - Đầu đường Tự Do - by Dr. William Bolhofer Thư Tình nơi Sofa ASIA

LITERARY REVIEW

Winter 2010 Modern Chinese Poetry -

Insistent Voices Landscape Above Zero It was the seagull that

taught the song to swim We shared shards of

happiness It was father who

recognized darkness The weeping door slammed

shut It was the pen that

bloomed in despair It was rays of love that

awoke Phong cảnh ở bên trên con số không Đó là hải âu dậy bài ca bơi Chúng ta chia nhau những

mảnh vụn của hạnh phúc Đó là người cha nhận ra

bóng tối Cánh cửa nức nở đóng sầm

lại Đó là cây viết nở hoa

trong chán chường Đó là những tia tình yêu

thức giấc Note: Bài

thơ này, có tới hai bản tiếng Mít, một của GCC, khi đọc Bei Dao trên tờ

Điểm

Văn Á, Asia Literary Review, mê quá [tại sao mê thì đừng bắt GCC phải

tự thú!]

Sau, gặp tập thơ của ông, bèn chơi liền, và được bạn Dã Viên dịch thẳng

từ tiếng

Tầu. Vị độc giả này, dân Huế, rất mê thơ. Rất giỏi tiếng Tầu. Trang TV

như vậy

là có thêm 1 vị hộ pháp! Tks All. NQT Phong cảnh trên độ không Là ó

biển dạy tiếng hát bơi Chúng

ta đổi trao những miểng vụn hân hoan Là

người cha xác nhận bóng tối Cánh

cửa nức nở đóng sầm lại Là bút

trổ bông trong tuyệt vọng Là tia

sáng tình yêu choàng tỉnh Bei Dao Dã Viên |