Vera

Kundera Beckett Thơ Thời Tao Loạn Chekhov by Italo Calvino Borges by Greene Raymond Carver The Secret Auden Zweig Ellroy Jackie Bergman Nhạc sĩ Trường Sa Kharms Shostakovich Nguyễn Huy Thiệp GGM Fowles Bloom Bolano Kafka Eyes Color Cynthia Ozick Jean Améry Nguyễn Tuân by Phan Ngọc Virginia Woolf Steiner Borges AZ Miloz Bio Bruno Schulz Everness Coetzee Vila-Matas Ondaatje Roth-Walcott Vallejo Rilke Milosz-Portrait Milosz Unbowed |

Chân Dung

Simenon’s Island of Bad DreamsIn Monsieur Monde Vanishes, one of the finest of what Simenon called his romans durs, or “hard” novels, the eponymous central character, a successful, middle-aged Parisian businessman, simply walks out of his life one day, without a word to anyone, including his wife and family. He takes a train to Marseilles and checks into an anonymous hotel, and next morning wakes from a dream in which he seemed to be weeping copiously and talking to himself: He was speaking without moving his lips, for which he had no need. He was telling of his infinite aching weariness, which was due not to his journey in a train but to his long journey as a man. He was ageless now. He could let his lips quiver like a child’s. “Always, for as long as I can remember, I’ve had to make such efforts …” It is a quintessential Simenon crise, in which a man who has spent his life in servitude to family, work, society, suddenly lays down his burden—“Lord, how tired he was now!”—and determines to live for the moment, and for himself, in full acceptance of the existential peril his decision will expose him to. Simenon understood well the desperation of Monsieur Monde, and of the many other similar characters he created, in the Maigret crime novels as well as in the romans durs. Simenon was a driven creature, who in his lifetime wrote more than four hundred books, drank and womanized incessantly, and, in his younger days, roamed the world in frantic search of he knew not what. His mother despised him; his long-suffering wife wrote a roman à clef in which she portrayed him as a rampaging egotist—“His voice rang through the house from morning to night, and when he was out it was as though the silence was awaiting his return.” Most calamitous of all, his daughter Marie-Jo, who adored and idolized him—as a child she asked him one day to buy her a gold wedding ring—killed herself at the age of twenty-five. He was, all his life, a spirit in flight from others and from himself, and he is present, often lightly disguised, in every one of his books. In The Mahé Circle, one of the romans durs translated now into English for the first time, the man on the run is François Mahé, or Dr. Mahé, as he is designated throughout, a small-town general practitioner whom we first meet holidaying with his family on the island of Porquerolles in the south of France, off the coast from Hyères. Dr. Mahé is suffering from a sense of general dissatisfaction. Since he was a child, he feels, “one could almost say that other people had been living his life for him.” He found that at thirty-five, here he was, too big, too fat, too full of rather vulgar life, with a wife and two children and an existence all laid out for him, a fixed schedule worked out for every day of the week. In short, he is bound to his family, which includes his mother, who lives with him still and who, “even today, … woke him in the morning, and told him when to change his underclothes.” The portrait of Madame Mahé, sketched in with the lightest yet most telling of strokes, shows Simenon at his sparest and best: She had a very gentle air about her. Her voice was soft. She looked after everyone, watched over everything, sat up at night with the children when they were ill. All the same, he was afraid of her. Porquerolles, where Mahé, his wife, and children are holidaying for the first time, proves to be less than a paradise; in fact, Mahé feels that on the island “things were hostile to him.” The sun is too hot, the sea too glaring, there are scorpions on land and grotesque conger eels in the water; it is “as if there was a tremendous chaos around him, a kind of life that was too vivid.” Then one day he is summoned to a squalid room in a disused barracks outside the village to attend a sick woman who has been living there with her roustabout husband, a former Foreign Legionnaire, and their three children. By the time he arrives, however, the woman has died. As he looks about the room, Mahé catches sight of “a red patch: a young girl, in a dress as scarlet as a flag, her thin legs bare, crouching in a corner, against the wall.” It seems a commonplace moment in a doctor’s life, and Mahé hardly gives a second thought to the woman’s death, or to the glimpse of her daughter in the red dress. The unsatisfactory holiday comes to an end and, relieved, the family returns home to Saint-Hilaire to resume their everyday lives. However, the image of that patch of red in the corner of the squalid room in which the woman died has lodged itself immovably in the dark reaches of Dr. Mahé’s mind. The best part of a year passes, and suddenly one Sunday in June when he is sitting in his garden, “his belly in front of him, because they had lunched well,” he finds that his “feeling of well-being was turning into a malaise.” What can be the matter? This year, it has been decided, the family for its annual holiday will return to the boarding house on the banks of the Sèvre that they had frequented for years, before the disastrous mistake that was Porquerolles. Yet now, on this strange and disturbing Sunday afternoon, Dr. Mahé hears himself announcing that they will, instead, go back to the island. The notion causes consternation, and drives the doctor’s timid and complaisant wife to tears: “She had been crying, sniffling rather, because she wasn’t capable of whole-hearted distress.” However, Mahé will not be moved: Porquerolles it will be. “And as he stood [in front of a mirror] looking at himself, his lips parted in a smile, a smile he had not seen for a long time, literally the smile of a little boy who has got his way.” Not that he clearly understands himself or his reasons for insisting on returning to a place where they all, himself included, had been so discomforted and unhappy. Looking out from the bow of the ferry as he approaches the island for the second time, “he would willingly have turned back, like his wife, but for different reasons.” Down there in the south was a hostile [that word again] world, a world so foreign to him that he felt quite lost. The island itself. Its throbbing heat as if in a belljar under the sun, the scorpion in his son’s bed, the deafening sound of the cicadas. Of course, we are aware of what it is that has brought him back, as is he, without admitting it to himself. Georges Simenon knew about many things, but the thing he knew most about was the nature of obsession. The persistence of Dr. Mahé’s memory of the girl and her red dress is uncanny—indeed, the image of the dress, which Simenon merely mentions a few times, almost in passing, has the nightmarish vividness of the child-sized red raincoat in Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now. And just as in that movie the main character ended up destroyed, so too will Mahé meet his nemesis on the island of his—bad—dreams. The Mahé Circle is a sort of masterpiece; one says “sort of” because the book does not call itself to our attention in any purely literary way. Simenon’s uniqueness is that he created high literature in seemingly low forms. This novel, like most of the romans durs, reads like a piece of pulp fiction: it is brief, fast-paced, with an air of the slapdash that is, however, wholly deceptive. True, Simenon wrote fast, and revised little. Yet his artistry is supreme. The account in this book of old Madame Mahé’s descent into illness and death is a sublime piece of writing, as good, in its unforced and unemphatic way, as anything in Proust or even Flaubert. Mahé himself is a wonderfully realized, appalling creation, but even more impressive are the minor characters, Mahé’s wife, for instance, who is barely noticed in the narrative and yet is entirely alive, or the father of the girl in the red dress, Frans Klamm, “as docile as a beast of burden”: He did what he was asked. He was the servant at everyone’s beck and call. People threw him coins. Or invited him on board a boat to finish up the remains of a stew. He would eat slowly, always sitting very still, and his gestures were oddly delicate, even if he was eating with his fingers.Chapeau, cher Maitre!

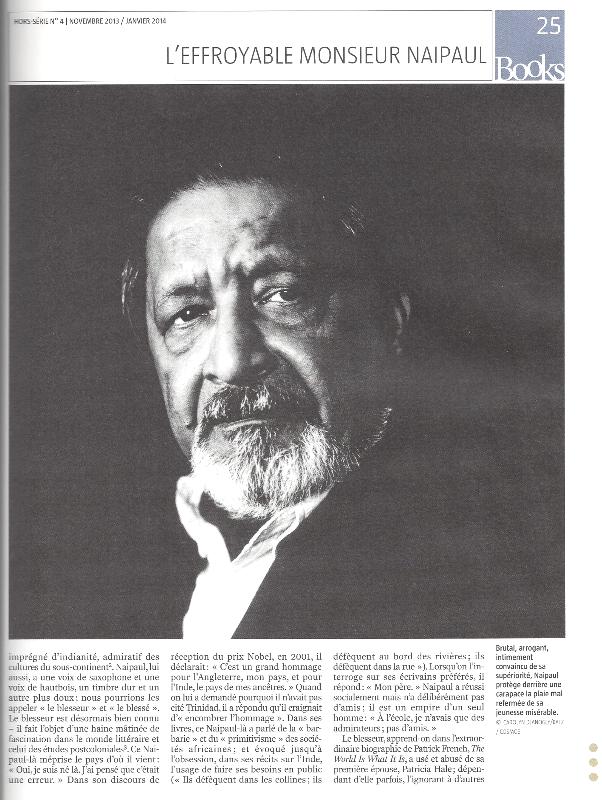

Tàn nhẫn, xấc xược, cực kỳ trịch thượng, giấu kín vết thương không thể nào lành, là 1 tuổi thơ khốn khổ của mình

His Exile Was Intolerable Tờ Books, Avril

2013, có 1 bài phạng Zweig tơi bời xí oắt, và tự hỏi, hà cớ làm sao

1 mà ông văn chương dở như hạch, lại được ca thấu trời. ZWEIG, CE PEPSI DE LA LITTERATURE A quoi est due l'immense popularité

dont continue de jouir Stefan Zweig? A une sorte de talent hollywoodien

fait pour plaire à la bourgeoisie inculte. Les Mann, Musil et autres

Canetti ne s'y trompaient pas, qui le couvraient de leur mépris. Un

poète anglais d' origine allemande enfonce le clou dans cet article

d'une rare méchanceté qui fracasse aussi la statue morale de l'humaniste.

MICHAEL HOFMANN. London Review of Books.

Chân Dung

Valentine's Day, 2013

Valentine's Last Year MY GIFT TO YOU My gift to you will be an abyss,

she said, Xuống phố, đổi phim, ghé tiệm

sách, mua số The Paris Review có

bài thơ tuyệt vời của Bolano, tả đúng tâm sự Gấu, đúng cái cảnh tình

cờ gặp lại Em, khi Em đi chợ Bến Thành, về, và “kín đáo” nói cho biết,

tại làm sao Em vờ Gấu, và chọn một anh bồ, cùng học Y Khoa. Quà BHD tặng Gấu Quà ta tặng mi sẽ là 1 vực thẳm,

em nói

Nhưng nó "tế vi" đến nỗi mi không thể nào nhận ra Chỉ sau thật nhiều năm, có khi, chỉ sau khi ta đi xa rồi, Và cả hai đều chạy ra khỏi cả hai quê hương Bắc Kít và Nam Kít rồi Thì lúc đó mi mới tìm thấy món quà ta tặng mi Khi mà mi cực cần đến nó Và chắc chắn không phải là một kết thúc hạnh phúc Nhưng sẽ là một thoáng chốc của sự trống rỗng và niềm vui. Và có thể, chỉ lúc đó mi mới nhớ ta, Và mới hiểu cái gọi là "mono no aware", “Nỗi buồn cháy da, cháy thịt khi ta đã đi ra khỏi đời của mi". Nhưng cũng chỉ được 1 tí tí. Chân Dung

Cái đẹp là cây đoản kiếm xoáy

vô ngực, hay tâm hồn độc giả

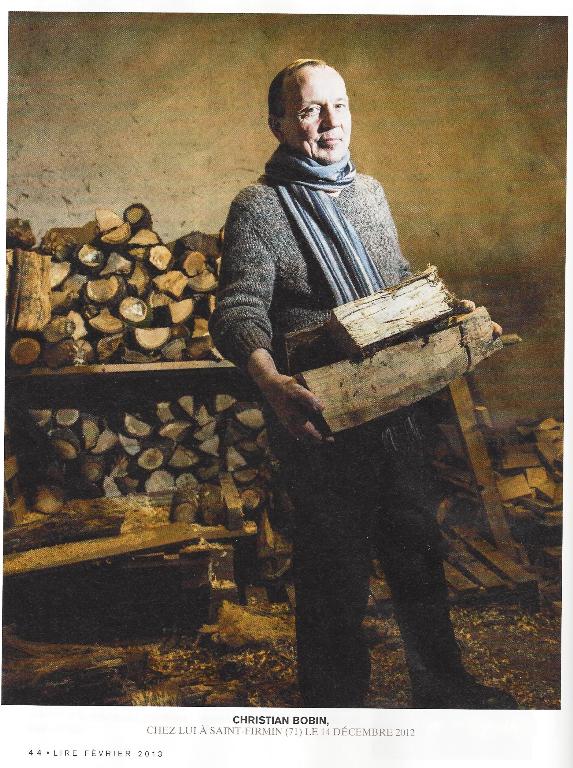

Note: Bài này thú vị lắm. Bobin

là tác giả đầu tiên Gấu khám phá ra, ngay những ngày đầu đến Xứ Lạnh,

không mắc mớ gì tới Lò Thiêu!

Cuốn này, Tẩy đọc sau Mít, nhưng

dịch cái tít khác hẳn, thay vì "Thôi rồi còn chi đâu em ơi", thì

là, "Gái Nhảy"! Nghĩ về phê bình

Hồi Ký Viết Dưới Hầm

Liao Yiwu: «Les flics chinois sont mes meilleurs

lecteurs» Before you enter

the grave Ghi chú trong ngày Marine biology Viết bên lề "Bên Thắng Nhục Địa dư quyết định số phận của

Mít,

hay là The Revenge of Geography: What the Map Tells Us About Coming Conflicts and the Battle Against Fate Cuộc trả thù của chữ S.

Bài gãi đúng chỗ ngứa [vết thương

hình chữ S] của Gấu Cà Chớn!

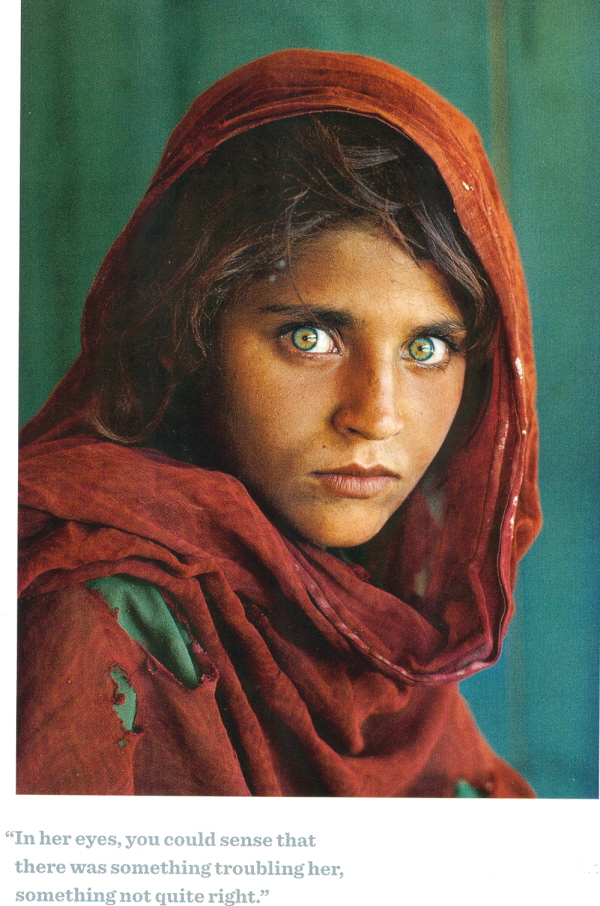

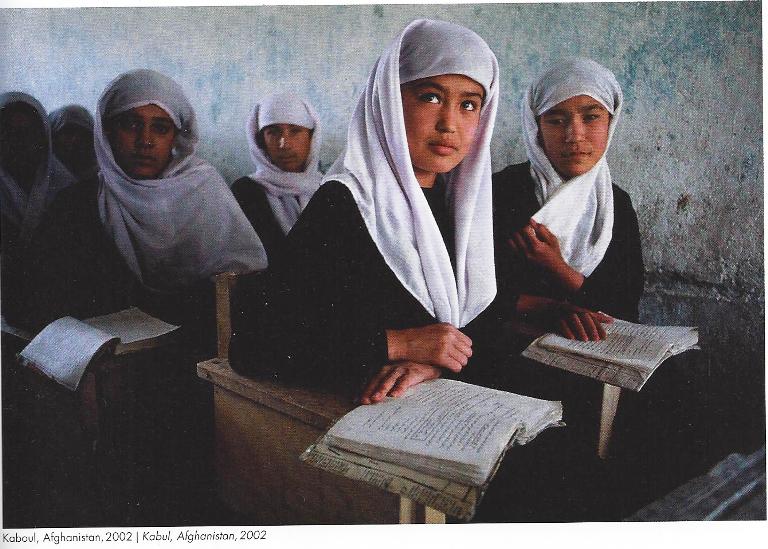

Nhìn mắt cô bé, là bạn biết

có cái gì làm phiền cô.

V/v Valentine’s Day Haunting eyes and a tattered

garment tell the plight of a girl who fled Afghanistan for a refugee

camp in Pakistan. Trong mắt của cô bé có vẻ dò

hỏi, có điều gì làm rộn cô, có điều gì không đúng, tại sao mi nhìn

ta như thế, hình như mi muốn kiếm 1 cái gì đó ở nơi ta, hình như mi

lầm ta với 1 cái gì đó... Nhưng, bằng cách nào mà BHD

lại ‘thấu thị’ ra tất cả, và, bèn bỏ Gấu, và vừa đi vừa ngoái lại, lắc đầu: She's seen more than she should

at such a young age. Cô bé nhìn thấy nhiều hơn nhiều so với tuổi

của cô. Mi “THNM” rồi, nhìn đâu cũng

thấy VC! Rõ ràng là cô bé nghèo. Mặt

cô nhem nhuốc, quần áo tơi tả, tuy nhiên, có cái gọi là phẩm hạnh, sự tin

tưởng…. Ố là là, nghe sướng điên lên được! (1)

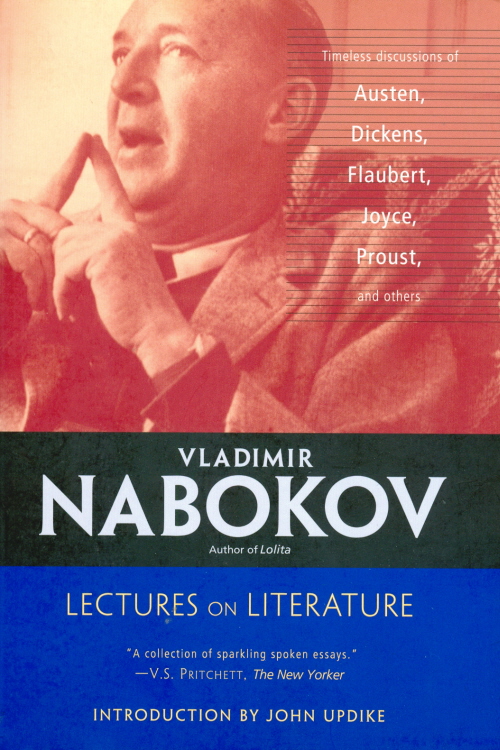

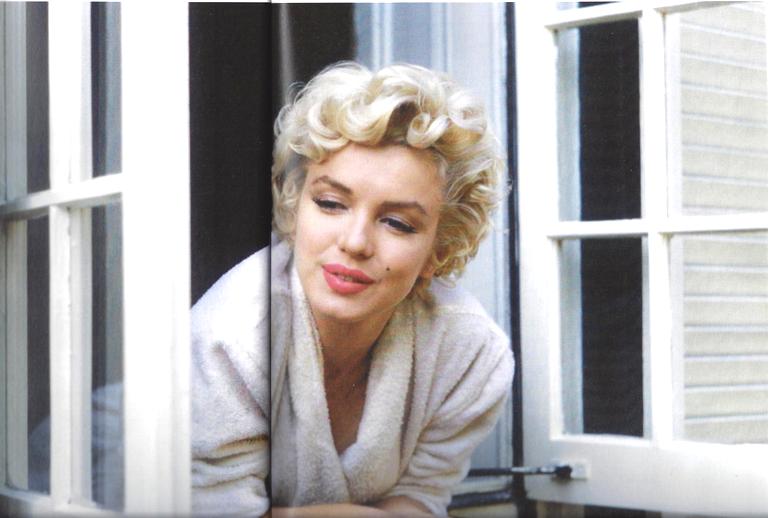

Mlle [Cô] Nabokov Select four answers to the question

what should a reader be to be a good reader: 1. The reader should belong

to a book club.

Quả có câu “Hãy chọn 4 câu trả

lời” GM dịch câu số 6 "Người đọc

là một tác giả mới vào nghề", sai. Bản tiếng Tây dùng un auteur en puissance

mạnh hơn nguyên tác tiếng Anh, có nghĩa 1 tác giả đang nẩy nở thành

1 tác giả. Thì cũng mắm sốt, nhưng “en puissance” nghe sung mãn hơn

nhiều! To GM: Tks. NQT … Như trong bài

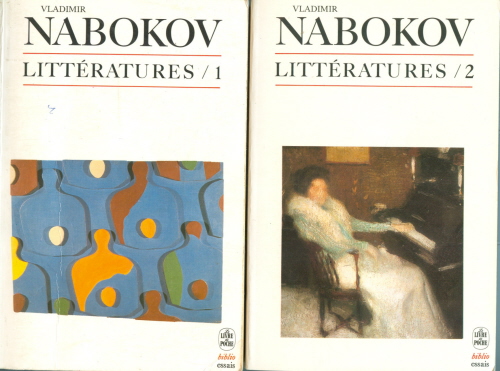

trích dẫn, "Người đọc tốt và người viết tốt" (trong Văn Chương tập

I, bản tiếng Pháp, nhà xb Fayard, loại sách bỏ túi), Nabokov phân biệt

giữa văn chương (giả tưởng, bịa đặt), và sự thực. Ông đã viết một cách

thật là "nặng nề": Văn chương là bịa đặt. Giả tưởng là giả tưởng. Gọi

câu chuyện là "chuyện thực", là làm nhục cả nghệ thuật lẫn sự thực. (La

littérature est invention. La fiction est fiction. Appeler une histoire

"histoire vraie", c'est faire injure à la fois à l'art et à la vérité.)

Vì sự thực liên quan tới hiện thực cho nên ông giải thích thêm: Thiên Nhiên

không ngừng đánh lừa. (La Nature trompe sans cesse). Ông viết: "Mọi nghệ

sĩ lớn đều là ảo thuật gia lớn, và cũng thế, Thiên Nhiên là tổ sư đại bịp....

Nhà văn của giả tưởng chỉ việc đi theo con đường Thiên Nhiên đã vạch ra"

(Tout grand écrivain est un grand illusionniste, mais telle également est

l'architrompeuse Nature.... L'écrivain de fiction ne fait que suivre la

voie tracée par la Nature.) Cả một cõi văn

chương, giả tưởng, như thế, là 1 trò bịp bợm. Những lời dối trá thực,

the true lies, tôi là lời dối trá nói lên sự thực. Tao là 1 tổ sư

đại bịp. Cả đời GCC, chỉ

có mỗi 1 giai đoạn thực sự muốn “thành thực và khiêm tốn”, là khi

talawas ra đời, với bà chúa Sến, vị nữ thủ lĩnh trên không gian ảo.

GCC mừng quá, nghĩ lúc này cố làm sao mà có được 1 nền văn học thực

sự giao lưu hòa giải, gồm đủ thứ… Kít, nào Bắc Kít, Nam Kít, Bắc Kí

di cư… nó sẽ thành 1 sức ép lên VC trong nước, đòi hỏi đổi mới, thay đổi

chế độ… Và, bị cả 1 lũ xúm lại đấm đá, đành ôm đầu máu chạy về núi Tản Viên!

Nabokov có mấy bài viết "tốt",

kèm với hai cuốn Văn Học trên, Nghệ

thuật dịch, Nghệ thuật văn và thiên lương, L’art de la literature

et le bon sens, Ðộc giả tốt, nhà văn tốt. Ðộc giả tốt còn

có cái tít khác, Nghệ thuật là độc giả.

Nếu là bài trắc nghiệm, thì

GCC chọn hai câu, độc giả tốt phải nhập

vào nữ nhân vật hoặc nam nhân vật, và câu, độc giả tốt là 1 tác giả đang trong thế hàm

mô công, chỉ chờ dịp giút súng bắn pằng pằng! [mượn chữ của GM] Giá có gặp một em còn trinh thì cũng thua thôi! Không phải GCC, mà là Steiner

phán nhe: |