|

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/06/04/philip-roths-propulsive-force

Tưởng niệm Philip Roth,

với GCC, là nhớ Sài Gòn của 1 thời Goodby-Columbus,

như Gấu vừa mới nhớ lại, với bóng dáng BHD, với cặp mắt ngỡ

ngàng, lần đầu gặp, khi cô bé 11 tuổi, mi yêu

ta ư, hình như cô bé muốn hỏi. Và cũng 1 kiểu

nhớ lại như thế, Gấu mua tờ The Paris Review, số mới nhất – như mua cuốn

của Roth, Tại sao viết – vì bài thơ tưởng niệm Dereck Walcott:

Bài thơ làm nhớ bài viết của Brodsky về nhà

thơ này: Hải TriềuÂm, “The Sound of the Tide”.

PHILIP ROTH Roth's vitality never dwindled, particularly on the page; the propulsive force that first announced itself in the late fifties, with "Defender of the Faith," "Eli, the Fanatic," and "Goodbye, Columbus," persisted for more than half a century, to the last elegiac description of a javelin thrower in "Nemesis," his career-closing novella. In interviews and public appearances, Roth could be slightly grand, ending an observation with an Anglo-ish "Do you know?" Talking about "the indigenous American berserk," he tamped down his more antic side, as if to stand apart from the madness. But, released from obligation, he could easily fup a switch and be once more the wiseacre of Weequahic. He was in competition with the best in American fiction-with Me1ville, James, Wharton, Hemingway, Faulkner, Cather, Ellison, Bellow, Morrison-but he was funnier, more spontaneous, than any of them. Recently, when I asked him what he thought of Bob Dylan's Nobel Prize, he said, "It's O.K., but next year I hope Peter, Paul and Mary get it." Most creative careers follow a familiar arc: the apprentice work; the burst of originality; the self-imitation; and, finally, the tailing off. Had Roth's creative career reached its pinnacle at the typical point, his achievements would still have included "Goodbye, Columbus,""Portnoy's Complaint,""The Ghost Writer," and "The Counterlife." But then Roth, having faced the crises of a failed marriage and a barrage of illnesses, redoubled his sense of discipline and set himself free. He became a monk of fiction. Living alone in the woods, he spent his days and many of his nights trained on the sentence, the page, the "problem of the novel at hand." Month after month, at a standing desk, he went about exploring American history (''American Pastoral," "I Married a Communist,""The Human Stain,""The Plot Against America") and, always, the miracles, the hypocrisies, the mistakes, the strangenesses of being alive while facing the inevitable "massacre" of aging. "I work, I'm on call," he told me in the midst of this creative ferment. "I'm like a doctor and it's an emergency room. And I'm the emergency." Roth's concentration on the task was absolute. When a friend left him with a kitten, he couldn't endure the distraction of having to provide food and attention. "I had to ask my friend to take it back," he recalled. I once asked him if he took a week off or a vacation. "I "cent to the Met and saw a big show they had," he told me. "It was wonderful. I went back the next day. Great. But what was I supposed to do next, go a third time? So I started writing again." Roth kept a little yellow note near his desk. It read "No Optional Striving." No panels, no speeches, no all-expenses-paid trips to the festival in Sydney or Cartagena. The work was murder and the work was the reward. Roth said he was never happier, never felt more liberated, than when he was working on his favorite of his novels, "Sabbath's Theater." Then, in 2010, at the age of seventy-seven, Roth did something utterly unexpected. He retired. He adored Saul Bellow-adored the work and the man-but he thought that Bellow had made a mistake by continuing to write and publish even as his mental acuity waned. Roth read his own work, the whole of it, and determined that he was done. Quoting Joe Louis, he said, "I did the best I could with what I had." And, in the last eight years of his life, Roth, living mostly in his apartment, near the Hayden Planetarium, gave himself the rest he had earned. He spent more time with friends, he read volumes of American and European history, he went to chamber-music concerts, he watched baseball and old movies. He appointed a biographer, Blake Bailey, and gave him what he needed "to do the job." With his competitiveness long faded, he became a reader, and a booster, of younger writers-Teju Cole, Nicole Krauss, Zadie Smith, Lisa Halliday. And he waited. He had had his portion, and then some. As he put it in "The Dying Animal," "You tasted it. Isn't that enough?" -David Remnick Nhà thơ sinh ra tại 1 xứ sở bị mũi lõ đô hộ, nhưng trở thành vĩnh cửu, immortalized, nhờ thơ của ông. Brodsky viết: The Sound of the Tide

I Because civilizations are finite, in the life of each of them comes a moment when centers cease to hold. What keep them at such times from disintegration is not legions but languages. Such was the case with Rome, and before that, with Hellenic Greece. The job of holding at such times is done by the men from the provinces, from the outskirts. Contrary to popular belief, the outskirts are not where the world ends-they are precisely where it unravels. That affects a language no less than an eye. Bởi là vì mọi nền văn minh thì đều hữu hạn, và sẽ tới 1 lúc, trung tâm không thể níu kéo, và, cái giữ cho nó khỏi rã ra, là biên cương… GCC đã từng dùng những dòng của Brodsky, trên, để viết về đám Bắc Kít sau 1975, bỏ chạy vào Sài Gòn… To put it differently, these poems represent a fusion of two versions of infinity: language and ocean. The common parent of these two elements is, it must be time. If the theory of evolution, especially that part of that suggests we all came from the sea, holds any then both thematically and stylistically Derek Walcott’s poetry is the case of the highest and most logical evolvement of the species. He was surely lucky to be born at outskirt, at this crossroads of English and the where both arrive in waves only to recoil. The same pattern of motion-ashore, and back to the horizon-is in Walcott's lines, thoughts, life. Major Jackson

Island traffic slows to a halt IN MEMORY OF DEREK ALTON WALCOTT 1

as screeching gulls reluctant to lift heavenward congregate like mourners in salt- crusted kelp, as the repellent news spreads to colder shores: Sir Derek is no more. Bandwidths, clogged by streaming tributes, carry the pitch of his voice, less so his lines, moored as they are to a fisherman's who strains in the Atlantic then hearing, too, drops his rod, the reel unspooling like memory till his gaped mouth matches the same look in his wicker creel, that frozen shock, eyes marble a different catch. Pomme-Arac trees, sea grapes, and laurels sway, wrecked having lost one who heard their leaves' rustic dialect as law, grasped thcir bows as edicts from the first garden that sowed faith - and believe he did, astonished at the bounty of light, like Adam, over Castries, Cas- en-Bas, Port of Spain, the solace of drifting clouds, rains like hymns then edens of grass, ornate winds on high verandas carrying spirits who survived that vile sea crossing, who floated up in his stanzas, the same souls Achille saw alive, the ocean their coffin- faith, too, in sunsets, horizons whose auric silhouettes divide and spawn reflection, which was his pen's work, devotion twinned with delight, divining like a church sexton. Poetry is empty without discipline, without piety, he cautions somewhere, even his lesser rhymes amount to more than wrought praise but amplify his poems as high prayer. So as to earn their wings above, pelicans move into tactical formation then fly low like jet fighters in honor of him, nature’s mouth, their aerial salute and goodbye. 2 Derek, each journey we make, whether Homeric or not, follows the literal wake of some other craft's launch, meaning to sense the slightest motions in unmoving waters is half the apprentice's training before he oars out, careful to coast, break- ing English's calm surface. What you admired in Eakins in conversation at some café (New Orleans? Philly?) was how his rower seemed to listen to ripples on the Schuylkill as much as to his breath, both silent on his speaking canvas. Gratitude made you intolerant of the rudeness of the avant- garde or any pronouncements of the "new;' for breathing is legacy and one's rhythm, though the blood's authentic transcription, hems us to ancestors like a pulse. This I fathom, is what you meant when exalting the merits of a fellow poet: that man is at the center of language, at the center of the song. Yet a reader belongs to another age and, likely to list our wrongs more than the strict triumphs of our verse, often retreats like a vanished surf, spume frothing on a barren beach. The allure of an artist's works these days is measured by his ethics, thus our books, scrubbed clean, rarely mention the shadowless dark that settles like an empire over a page. Your nib, like the eye of a moon, flashed into sight the source of Adam's barbaric cry. 3 Departed from paradise, each Nobody a sacrifice, debating whose lives matter whereon a golden platter our eyes roll dilated by hate from Ferguson to Kuwait. You, maitre, gave in laughter but also for the hereafter an almost unbearable truth: we are the terrible history of warring births destined for darkest earth. So as cables of optic lights bounce under oceans our white pain, codified as they are and fiber-layered in Kevlar, we hear ourselves in you, where "race" exiles us to stand lost as single nations awaiting your revelations. A shirtless boy, brown as bark, gallops alongshore, bareback and free on a horse until he fades, a shimmering, all that remains. The Paris Review 224, Spring 2018 Note: GCC sẽ dịch bài thơ, song song với bài viết của Brodsky, về Walcott, 1 trong số những bài ông viết về thơ và thi sĩ, mà, đến lúc này, thì Gấu mới nghĩ là mình đọc được, hiểu đuợc. Cũng là 1 cách thực hiện lời chúc SN của K: Chỉ làm thơ thôi.

http://www.tanvien.net/Viet/A_Place_In_The_Country.html

The Genius of Robert Walser http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2000/nov/02/the-genius-of-robert-walser/ J.M. Coetzee November 2, 2000 Issue Was Walser a great writer? If one is reluctant to call him great, said Canetti, that is only because nothing could be more alien to him than greatness. In a late poem Walser wrote: I would wish it on no one to be me. Only I am capable of bearing myself. To know so much, to have seen so much, and To say nothing, just about nothing. Walser, nhà văn nhớn? Nếu có người nào đó, gọi ông ta là nhà văn nhớn, 1 cách ngần ngại, thì đó là vì cái từ “nhớn” rất ư là xa lạ với Walser, như Canetti viết. Như trong 1 bài thơ muộn của mình, Walser viết: Tớ đếch muốn thằng chó nào như tớ, hoặc nhớ đến tớ, hoặc lèm bèm về tớ, hoặc mong muốn là tớ Nhất là khi thằng khốn đó ngồi bên ly cà phê! Một mình tớ, chỉ độc nhất tớ, chịu khốn khổ vì tớ là đủ rồi Biết thật nhiều, nhòm đủ thứ, và Đếch nói gì, về bất cứ cái gì [Dịch hơi bị THNM. Nhưng quái làm sao, lại nhớ tới lời chúc SN/GCC của K!] Walser được hiểu như là 1 cái link thiếu, giữa Kleist và Kafka. “Tuy nhiên,” Susan Sontag viết, “Vào lúc Walser viết, thì đúng là Kafka [như được hậu thế hiểu], qua lăng kính của Walser. Musil, 1 đấng ái mộ khác giữa những người đương thời của Walser, lần đầu đọc Kafka, phán, ông này thuổng Walser [một trường hợp đặc dị của Walser]." Walser được ái mộ sớm sủa bởi những đấng cự phách như là Musil, Hesse, Zweig. Benjamin, và Kafka; đúng ra, Walser, trong đời của mình, được biết nhiều hơn, so với Kafka, hay Benjamin. W. G. Sebald, in his essay “Le Promeneur Solitaire,” offers the following biographical information concerning the Swiss writer Robert Walser: “Nowhere was he able to settle, never did he acquire the least thing by way of possessions. He had neither a house, nor any fixed abode, nor a single piece of furniture, and as far as clothes are concerned, at most one good suit and one less so…. He did not, I believe, even own the books that he had written.” Sebald goes on to ask, “How is one to understand an author who was so beset by shadows … who created humorous sketches from pure despair, who almost always wrote the same thing and yet never repeated himself, whose prose has the tendency to dissolve upon reading, so that only a few hours later one can barely remember the ephemeral figures, events and things of which it spoke.”

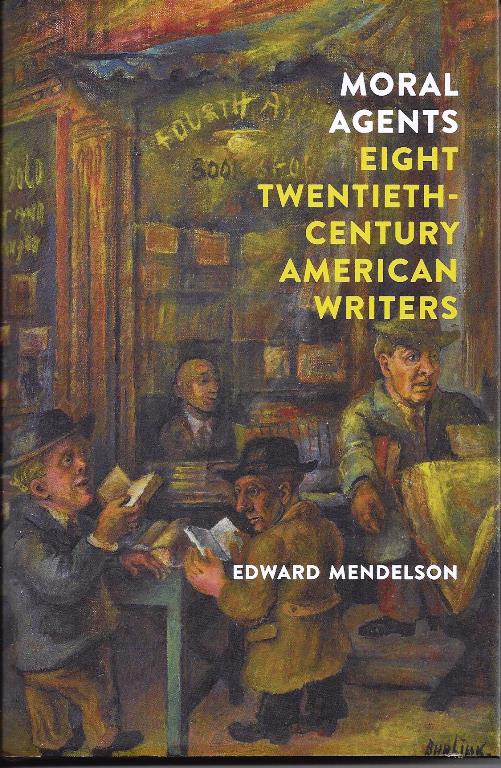

Bài viết của Coetzee về Walser, sau đưa vô “Inner Workings, essays 2000-2005”, Gấu đọc rồi, mà chẳng nhớ gì, ấy thế lại còn lầm ông với Kazin, tay này cũng bảnh lắm. Từ từ làm thịt cả hai, hà hà! Trong cuốn “Moral Agents”, 8 nhà văn Mẽo tạo nên cái gọi là văn hóa Mẽo, Edward Mendelson gọi Lionel Trilling là nhà hiền giả (sage), Alfred Kazin, kẻ bên lề (outsider), W.H, Auden, người hàng xóm (neighbor)… Bài của Coetzee về Walser, GCC mới đọc lại, không có tính essay nhiều, chỉ kể rông rài về đời Walser, nhưng mở ra bằng cái cảnh Walser trốn ra khỏi nhà thương, nằm chết trên hè đường, thật thê lương: On Christmas Day, 1956, the police of the town of Herisau in eastern Switzerland were called out: children had stumbled upon the body of a man, frozen to death, in a snowy field. Arriving at the scene, the police took photographs and had the body removed. The dead man was easily identified: Robert Walser, aged seventy-eight, missing from a local mental hospital. In his earlier years Walser had won something of a reputation, in Switzerland and even in Germany, as a writer. Some of his books were still in print; there had even been a biography of him published. During a quarter of a century in mental institutions, however, his own writing had dried up. Long country walks—like the one on which he had died—had been his main recreation. The police photographs showed an old man in overcoat and boots lying sprawled in the snow, his eyes open, his jaw slack. These photographs have been widely (and shamelessly) reproduced in the critical literature on Walser that has burgeoned since the 1960s Walser’s so-called madness, his lonely death, and the posthumously discovered cache of his secret writings were the pillars on which a legend of Walser as a scandalously neglected genius was erected. Even the sudden interest in Walser became part of the scandal. “I ask myself,” wrote the novelist Elias Canetti in 1973, “whether, among those who build their leisurely, secure, dead regular academic life on that of a writer who had lived in misery and despair, there is one who is ashamed of himself.”

|