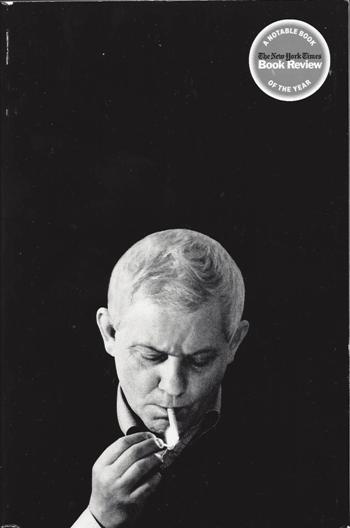

ZBIGNIEW

HERBER

ZBIGNIEW

HERBER

Tuyển tập thơ 1956-1998

INTRODUCTION

by ADAM

ZAGAJEWSKI

WHERE DID

HERBERT come from; where did his poetry come from? The simplest answer

is: We

don't know. Just as we never know where any great artist comes from,

irrespective of whether they are born in the provinces or in the

capital. Yet

here we cannot merely content ourselves with our mystic ignorance!

American

readers undoubtedly deserve a short biographical sketch:

Zbigniew

Herbert, born in Lwow in 1924, led a life that especially in his youth

was full

of adventure and danger, though one is tempted to say that he was

.created

rather for a quiet existence between museum and library. There are

still many

things we do not know about the wartime period of his life-to what

extent he

was engaged in the resistance, or what he experienced during the

occupation. We

know that he came from what is called in English the "middle

classes," and in Polish is known as the intelligentsia. The relative,

or

perhaps truly profound, orderliness of his childhood was destroyed once

and for

all in September 1939 by the outbreak of war. First Nazi Germany, then

seventeen days later the Soviet Union, invaded the territory of Poland.

At that

time Wehrmacht units did not make it as far as Lwow; the city, which

was filled

with refugees from central Poland, was occupied by the Red Army-and by

the

NKVD, the secret police, who immediately set about arresting thousands

of

Poles, Jews, and Ukrainians. The sudden leap from the last pre-war

vacation to

Stalin's terror must have been unbelievably brutal. Many elements of

Herbert's

poetry undoubtedly originated from this experience.

In the last days of June

1941 the Soviet occupation of Lwow

ended and the Nazi occupation began. Distinguishing between the two

occupations

is a matter for academics. Of course, one major difference was that now

the

persecutions were aimed mostly, though not exclusively, at Jews.

When the war ended and

Lwow was incorporated into the

territory of the Soviet Union, Herbert was one of thousands of young

people

living in abeyance, trying to study, and hiding their underground past.

Hard as

it will be for a western reader to believe, the new authorities imposed

by

Moscow persecuted former resistance fighters simply for having fought

in their various

ways against the Nazi invader. Their crime was to have been

connected-often

without fully being aware of it, since they operated at a local level

and

mostly carried out specific, small-scale assignments-with the Polish

government

in exile in London rather than the communist partisan movement. The new

government applied to them a policy that was the exact opposite of the

American

GI Bill, putting obstacles in their way, sometimes imprisoning them,

and

sometimes even sentencing them to death.

The whole time up till

1956, when a political thaw altered

the situation for the better, Herbert led an unsettled existence,

changing

addresses frequently, moving around between Gdansk, Warsaw, Torun, and

Krakow, and

taking on various jobs (when he was short of money he even sold his own

blood,

a painfully accurate metaphor for the life of a poet). He studied

philosophy,

wondering whether or not he should devote himself to it full time. He

was also

drawn to art history. For political reasons he was unable to bring out

his

first book of poetry, but he began to publish individual poems and book

reviews; the periodical he was most involved with was Tygodnik-

Powszechny, a liberal-Catholic weekly based in Krakow.

He was not completely

isolated; he had friends in various

cities, and lovers; he also had an intellectual mentor. This was Henryk

Elzenberg, at the time a professor of the University of Torun, an

erudite

philosopher and poet, a tireless researcher of intellectual formulae,

and an

independent type barely tolerated by the new regime. A volume of

correspondence

between teacher and student published recently (in 2002) reveals a

melancholic

professor and a witty student frequently excusing himself before his

mentor for

real or imagined failures. In these letters Herbert is contrary and

obedient, inventive,

talented, no doubt aware of his epistolary charms, but still timid, a

little

afraid of his strict Master, not entirely sure whether he should become

a

philosopher or a poet, demanding emotion in philosophy and ideas in

poetry,

averse to closed systems, droll, at once ironic and warm.

The year 1956, as I

mentioned, changes almost everything for

Herbert. His debut, Chord of Light,

is enthusiastically received. Suddenly, thanks to the thaw; the borders

of Europe

are pen to him, to some extent at least; he can visit Prance, Italy,

London.

Prom this moment there begins a new chapter in his life, one that was

to last

almost to his final month – he died in July 1998. A truly different

chapter-yet

if one looks at it closely, it is oddly similar to the preceding one.

Now,

admittedly, Herbert travels amongst Paris, Berlin, Los Angeles, and

Warsaw; the

length of his journeys is much greater than before, and he becomes a

world-famous poet. But the fundamental unrest and the underlying

instability

(including financially) are still there. In addition there is an

encroaching

illness. Only the surroundings are more beautiful; they include the

greatest

museums of the world, in which breathless tourists can see a Polish

poet

diligently and calmly sketching the works of great artists in his

notebook. For

once again he has masters: Henryk Elzenberg's place has now been taken

by

Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Piero della Francesca, and also the "old

masters" from the magnificent poem in Report

from a Besieged City.

He also had mentors and

teachers in poetry. He learned a

great deal from Czeslaw Milosz, with whom he was friends (they had met

for the

first time in Paris in the second half of the 1950s). He was thoroughly

familiar

with the Polish romantic poets and with old and modern European poetry.

He

certainly read Cavafy. He studied the classical authors-studied them

the way

poets do, unsystematically, falling in and out of love, jumping from

period to

period, finding the things that were important for him and discarding

those

that interested him less; in doing so he acted quite differently from a

scholar, who moves like a solid tank of erudition through the period he

has

selected. He also read dozens of historical works on Greece, Holland,

and

Italy. He sought to understand the past. He loved the past-as an

aesthete,

because he was fascinated by beauty, and as a man who quite simply

looked in

history for the traces of others.

EVERY GREAT

POET lives between two worlds. One of these is the real, tangible world

of

history, private for some and public for others. The other world is a

dense

layer of dreams, imagination, and phantasms. It sometimes happens-as

for

example in the case of W B. Yeats-that this second world takes on

gigantic

proportions, that it becomes inhabited by numerous spirits, that it is

haunted

by Leo Africanus and other ancient magi.

These two territories

conduct complex negotiations, the

result of which are poems. Poets strive for the first world, the real

one,

conscientiously trying to reach it, to reach the place where the minds

of many

people meet; but their efforts are hindered by the second world, just

as the dreams

and hallucinations of certain sick people prevent them from

understanding and

experiencing events in their walking

hours. Except that in great poets these hindrances are rather a symptom

of

mental health, since the world is by nature dual, and poets pay tribute

with

their own duality to the, true structure of reality, which is composed

of day

and night, sober intelligence and fleeting fantasies, desire and

gratification.

There is no poetry without

this duality, though the second,

substitute world is different for each outstanding creative artist.

What is it

like for Herbert? Herbert's dreams are sustained by various

things-travels,

Greece and Florence, the work of great painters, ideal cities (which he

saw

only in the past, not in the future, unlike many of his

contemporaries). But

they are also sustained by the knightly virtues of honor and courage.

Herbert himself helps us

to understand his poetry in "Mr

Cogito and Imagination." Because Mr Cogito:

longed to fully comprehend

-Pascal's night

-the nature of diamonds

-the melancholy of the

prophets

-the wrath of Achilles

-the madness of genocides

-the dreams of Mary Queen

of Scots

-the Neanderthal's fear

-the despair of the last

Aztecs

-the long dying of

Nietzsche

-the joy of the Lascaux

painter

-the rise and fall of an

oak

-the rise and fall of Rome

Achilles and an oak,

Lascaux and a Neanderthal's fear, the

despair of the Aztecs-these are the ingredients of Herbert's

imagination. And

always "rise and fall" -the entirety of the historical cycle. Herbert sometimes likes to assume the position

of a rationalist and so in his beautiful poem he says of these

unfathomable

things that Mr Cogito longed to "fully comprehend" them, something

that is of course (fortunately) impossible.

But for Herbert the matter

is even more complicated. In him

we find two central intellectual problems-participation and distance.

He never forgot

the horror of war and the invisible moral obligations he incurred

during the

occupation. He himself spoke of loyalty as a leading ethical and

aesthetic

yardstick. Yet he was diff rent from other poets such as Krzysztof

Kamil Baczynski,

the great bard of the wartime generation, who died very young (in the Warsaw Uprising), and whose poems were

imbued with the heat of burning metaphors. No, Herbert is not like that

at all:

In him the level of wartime horror is seen from a certain distance.

Even in the

direst circumstances the heroes of Herbert's poems do not lose their

sense of

humor. And in the poems and essays the tragic poet steps out alongside

the

carefree Mr. Pickwick, who does not imagine that he has deserved such a

great

misfortune. It may be here that there lies the particular, indefinable

charm of

both Herbert's poetry and his essays-this tragicomic mixing of tones,

the fact

that the utmost gravity in no way excludes joking and irony. But the

irony

mostly concerns the character of the poet, or that of his porte-parole

M r.

Cogito, who is by and large a most imperfect fellow. While as concerns

the

message of this poetry-and it is poetry with a message, however

obscure-the

irony does not affect it whatsoever.

The need for distance: We

can imagine to ourselves (I like to

think about this) a youthful Herbert, who in occupied Lwow is looking

through

albums of Italian art, perhaps paintings of the Sienese quatrocento,

perhaps

reproductions of Masaccio’s frescoes. He's sitting in an armchair with

a album on

his lap; maybe he's at a friend's place, or maybe at home-while outside

the

window there can be heard the shouts of German (or Soviet) soldiers.

This

situation-the frescoes of Masaccio (or Giotto) and the yells of

soldiers coming

from outside-was fixed permanently in Herbert imagination. Wherever he

was,

however many years had passed since the war, he could hear the soldiers

shouting

outside the window-even in Los Angeles and the (once) quiet Louvre, in

the now

closed Dahlem Museum in Berlin (its collections transferred to a modern

building on Potsdamer Platz) or in his Warsaw apartment. Beauty is not

lonely;

beauty attracts baseness and evil-or in any case encounters them

frequently.

The paradox of Herbert,

which is perhaps especially striking

in our modern age, also resides in the fact that though he refers

willingly and

extensively to existing "cultural texts" and takes symbols from the

Greeks anywhere else, it is never in order to become a prisoner of

those references

and meanings - he is always lured by reality. Take the well-known poem

“Apollo

and Marsyas." It is constructed on a dense, solid foundation of myth.

An inattentive

reader might say (as inattentive critics have in fact said) that this

is an

academic poem, made up of elements of erudition, a poem inspired by the

library

and the museum. Nothing could be more mistaken: Here we are dealing not

with

myths or an encyclopedia, but with the pain of a tortured body.

And this is the common

vector of all Herbert’s poetry; let us

not be misled by its adornments, its nymphs and satyrs, its columns and

quotations.

This poetry is about the pain of the twentieth century, about accepting

the

cruelty of an inhuman age, about an extraordinary sense of reality. And

the

fact that at the same time the poet loses none of his lyricism or his

sense of

humor-this is the unfathomable secret of a great artist.

(Translated

by Bill Johnston)