|

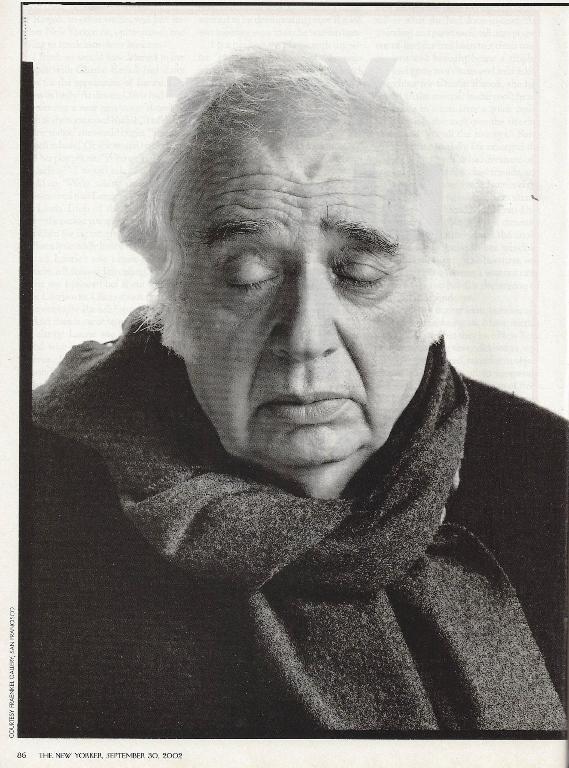

HAILED AS "the indispensable critic" by The

New York Review of Books, Harold Bloom- New York Times bestselling writer

and Sterling Professor of Humanities at Yale University- has for decades

been sharing with readers and students his genius and passion for understanding

literature and explaining why it matters. Now he turns at long last to his

beloved writers of our national literature in an expansive and mesmerizing

book that is one of his most incisive and profoundly personal to date. A

product of five years of writing and a lifetime of reading and scholarship,

The Daemon Knows may be Bloom's most masterly book yet. Pairing Walt Whitman

with Herman Melville, Ralph Waldo Emerson with Emily Dickinson, Nathaniel

Hawthorne with Henry James, Mark Twain with Robert Frost, Wallace Stevens

with T. S. Eliot, and William Faulkner with Hart Crane, Bloom places these

writers' works in conversation with one another, exploring their relationship

to the "daemon" -the spark of genius or Orphic muse-in their creation and

helping us understand their writing with new immediacy and relevance. It

is the intensity of their preoccupation with the sublime, Bloom proposes,

that distinguishes these American writers from their European predecessors.

As he reflects on a lifetime lived among the works explored in this book,

Bloom has himself, in this magnificent achievement, created a work touched

by the daemon.

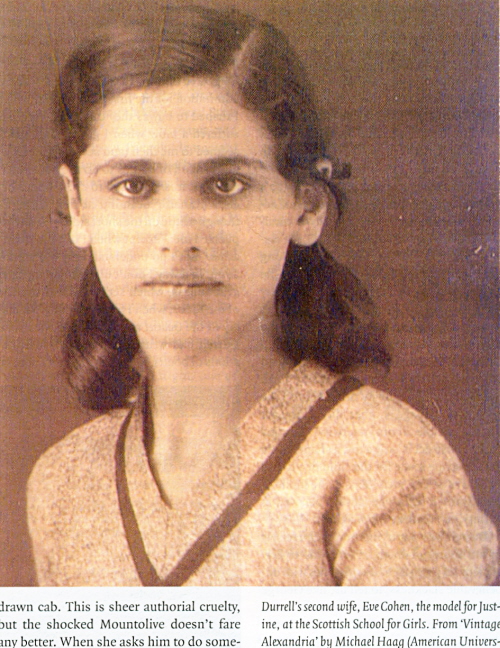

“Nhà tiên tri của thoái trào”, “nhà phê bình không thể nào bỏ qua”, xuất sắc nhất, không phải thời nào Mít - ấy chết xin lỗi – Yankee mũi lõ có thể sản xuất ra được, trong hàng chục niên làm giáo sư, Bloom chia sẻ với sinh viên và độc giả của mình, thiên tài và đam mê của ông trong cái sự hiểu biết văn học, và giải thích cái sự tình tại sao lại như thế, why it matters. Bi giờ, ông xoáy vào một số nhà nhà văn nhà thơ Yankee mũi lõ yêu quí của ông, và, thuổng thày Phúc, ông cứ cho 1 ông đứng kế một ông, và kết quả có được, là Quỉ Hiểu, The Daemon Knows. Từ daemon này, độc giả Tin Văn đã từng gặp nó, khi đọc Tứ Tấu Khúc Alexandria của Durrell. Ở đây, nó có nghĩa khác, với Bloom: the spark of genius, or Orphic muse, ánh thiên tài loé lên, hay nữ thần Orphic [từ Orpheus]. Mít kêu là phút linh cầu, “phiện thú lắm” [inspiration].

Justine Hãy

chừa riêng ra cho anh,

những vết thương tình mà anh chia sẻ với Sài Gòn.

(Épargne-moi les blessures de l’amour partagé avec Justine). Lũ đàn ông chúng mình, đều được tạo ra bằng bùn và quỉ ma của Sài Gòn. GCC đọc Bloom lèm bèm về Wakefield, thấy thua xa Borges, khi viết về trưyện ngắn này

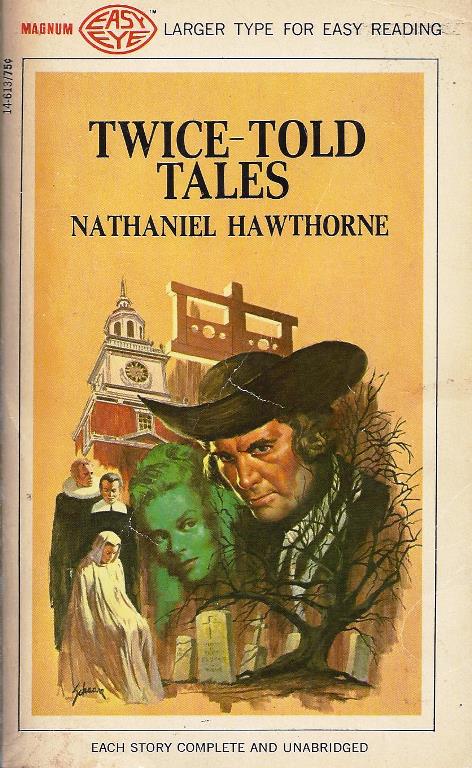

Một câu thần sầu, Borges vinh danh Hawthorne, TV gửi tới bạn đọc:

Khi Hawthorne mất, những nhà văn khác thừa hưởng ông, cái nhiệm vụ nằm mơ, và, như… GCC, khóc thảm thiết, cứ như là đang sống những ngày Mậu Thân, ở Xề Gòn. When Hawthorne died, the other writers inherited his task of dreaming. Borges viết thêm: Trong 1 thời gian nào đó ở tương lai, chúng ta sẽ nghiên cứu - nếu bạn đọc TV cho phép- vinh quang và sự dằn vặt, the glory and the torment, của Poe, qua ông, giấc mơ bị đẩy tới mức biến thành ác mộng.the dream was exalted to a nightmare. Hãy làm thịt Hawthorne trước đã.  Chuyện Kể

Hai Lần. Trong cuốn này, có cả hai truyện, The

Ambitious Guest và Wakefield.

Borges viết, Hawthorne cố hiểu nó, loay hoay hoài với nó, tức

“Wakefield”, câu

chuyện 1 người chồng đi hoang [lưu vong] hai chục niên, vì vợ:

“Wakefield” is

the conjectural [phỏng đoán] story of that exile.  Hawthorne had read in a newspaper, or pretended for literary reasons that he had read in a newspaper, the case of an Englishman who left his wife without cause, took lodgings in the next street and there, without any- one's suspecting it, remained hidden for twenty years. During that long period he spent all his days across from his house or watched it from the comer, and many times he caught a glimpse of his wife. When they had given him up for dead, when his wife had been resigned to widowhood for a long time, the man opened the door of his house one day and walked in-simply, as if he had been away only a few hours. (To the day of his death he was an exemplary husband.) Hawthorne read about the curious case uneasily and tried to understand it, to imagine it. He pondered on the subject; "Wakefield" is the conjectural story of that .exile, The interpretations of the riddle can be infinite; let us look at Hawthorne's. He imagines Wakefield to be a calm man, timidly vain, selfish, given to childish mysteries and the keeping of insignificant secrets; a dispassionate man of great imaginative and mental poverty, but capable of long, leisurely, inconclusive, and vague meditations; a constant husband, by virtue of his laziness. One October evening Wakefield bids farewell to his wife. He tells her-we must not forget we are at the beginning of the nineteenth century -that he is going to take the stagecoach and will return, at the latest, within a few days. His wife, who knows he is addicted to inoffensive mysteries, does not ask the reason for the trip. Wakefield is wearing boots, a rain hat, and an overcoat; he carries an umbrella and a valise. Wakefield-and this surprises me-does not yet know what will happen. He goes out, more or less firm in his decision to disturb or to surprise his wife by being away from home for a whole week. He goes out, closes the front door, then half opens it, and, for a moment, smiles. Years later his wife will remember that last smile. She will imagine him in a coffin with the smile frozen on his face, or in paradise, in glory, smiling with cunning and tranquility. Everyone will believe he has died but she will remember that smile and think that perhaps she is not a widow. Going by a roundabout way, Wakefield reaches the lodging place where he has made arrangements to stay. He makes himself comfortable by the fireplace and smiles; he is one street away from his house and has arrived at the end of his journey. He doubts; he congratulates himself; he finds it incredible to be there already; he fears that he may have been observed and that someone may inform on him. Almost repentant, he goes to bed, stretches out his arms in the vast emptiness and says aloud: "I will not sleep alone another night." The next morning he awakens earlier than usual and asks himself, in amazement, what he is going to do. He knows that he has some purpose, but he has difficulty defining it. Finally he realizes that his purpose is to discover the effect that one week of widowhood will have on the virtuous Mrs. Wakefield. His curiosity forces him into the street. He murmurs, "I shall spy on my home from a distance." He walks, unaware of his direction; suddenly he realizes that force of habit has brought him, like a traitor, to his own door and that he is about to enter it. Terrified, he turns away. Have they seen him? Will they pursue him? At the comer he turns back and looks at his house; it seems different to him now, because he is already another man-a single night has caused a trans- formation in him, although he does not know it. The moral change that will condemn him to twenty years of exile has occurred in his soul. Here, then, is the beginning of the long adventure. Wakefield acquires a reddish wig. He changes his habits; soon he has established a new I routine. He is troubled by the suspicion that his absence

Quà SN của Xì Lô.

Cuốn này về lâu rồi, đọc sơ sơ ở tiệm vài lần rồi, nhưng không dám bệ về.

Trong những cuốn của Bloom mà Gấu có, cuốn này bảnh nhất, dù mới đọc thoáng

qua. Viết về 12 đấng số 1 của văn học Mẽo.

HAILED AS "the indispensable critic" by The New York Review of Books, Harold Bloom- New York Times bestselling writer and Sterling Professor of Humanities at Yale University- has for decades been sharing with readers and students his genius and passion for understanding literature and explaining why it matters. Now he turns at long last to his beloved writers of our national literature in an expansive and mesmerizing book that is one of his most incisive and profoundly personal to date. A product of five years of writing and a lifetime of reading and scholarship, The Daemon Knows may be Bloom's most masterly book yet. Pairing Walt Whitman with Herman Melville, Ralph Waldo Emerson with Emily Dickinson, Nathaniel Hawthorne with Henry James, Mark Twain with Robert Frost, Wallace Stevens with T. S. Eliot, and William Faulkner with Hart Crane, Bloom places these writers' works in conversation with one another, exploring their relationship to the "daemon" -the spark of genius or Orphic muse-in their creation and helping us understand their writing with new immediacy and relevance. It is the intensity of their preoccupation with the sublime, Bloom proposes, that distinguishes these American writers from their European predecessors. As he reflects on a lifetime lived among the works explored in this book, Bloom has himself, in this magnificent achievement, created a work touched by the daemon.

|