|

Hãy yêu người bằng một thứ

tình yêu cũ xì, cằn cỗi vì thương hại, cáu

kỉnh và cô đơn.

"Aimer les hommes d'un vieil amour usé par la pitié, la colère, et la solitude". C. Milosz: Hành Trình qua Tây Phương. Tuyệt cú! Note: Bản tiếng Anh, của Milosz, cùng trong bài viết: To love people with an old love worn by pity, anger, and loneliness READING THE JAPANESE POET ISSA (1762-1826) A good world- dew drops fall by ones, by twos A few strokes of ink and there it is. Great stillness of white fog, waking up in the mountains, geese calling, a well hoist creaking, and the droplets forming on the eaves. Or perhaps that other house. The invisible ocean, fog until noon dripping in a heavy rain from the boughs of the redwoods, sirens droning below on the bay. Poetry can do that much and no more. For we cannot really know the man who speaks, what his bones and sinews are like, the porosity of his skin, how he feels inside. And whether this is the village of Szlembark above which we used to find salamanders, garishly colored like the dresses of Teresa Roszkowska, or another continent and different names. Kotarbinski, Zawada, Erin, Melanie. No people in this poem. As if it subsisted by the very disappearance of places and people. A cuckoo call For me, for the mountain For me, for the mountain Sitting under his lean-to on a rocky ledge listening to a waterfall hum in the gorge, he had before him the folds of a wooded mountain and the setting sun which touched it and he thought: how is it that the voice of the cuckoo always turns either here or there? This could as well not be in the order of things. In this world we walk on the roof of Hell gazing at flowers To know and not to speak. In that way one forgets. What is pronounced strengthens itself. What is not pronounced tends to nonexistence. The tongue is sold out to the sense of touch. Our human kind persists by warmth and softness: my little rabbit, my little bear, my kitten. Anything but a shiver in the freezing dawn and fear of oncoming day and the overseer's whip. Anything but winter streets and nobody on the whole earth and the penalty of consciousness. Anything but. Berkeley, 1978 Czeslaw Milosz: New and Selected Poems, 1931-2001 31.

SOMETIMES AT NIGHT or in the early morning, the phrases-the

lines-come back to me like talismans, like hard-won messages, metaphysical

truths, prayers, offerings from the deep. I was in my early twenties

when I first read Czeslaw Milosz's work, which has stayed with me

ever since as a touchstone of modern poetry itself I first felt from

his work the nobility and grandeur of poetry, yet also learned from

him to distrust rhetoric, to question false words and sentiments. CZESLAW MILOSZ I ask not out of sorrow, but in wonder. -"ENCOUNTER" The first movement is joy, But it is taken away. -"THE POOR POET" What is poetry which does not save Nations or people? -"DEDICATION" Human reason is beautiful and invincible. -"INCANTATION" The purpose of poetry is to remind us how difficult it is to remain Just one person ... -"ARS POETICA" And the heart does not die when one thinks it should ... -"ELEGY FOR N. N." What was accepted in bitterness and misery turned into praise ... -"FROM THE RISING OF THE SUN" There are nothing but gifts on this poor, poor earth. -"THE SEPARATE NOTEBOOKS" "Try to understand this simple speech as I would be ashamed of another," he avowed in "Dedication." "I swear, there is in me no wizardry of words." One felt from the beginning the purposefulness of Milosz's deceptive simplicity, his distrust of "pure poetry," his anguished irony, his humility before the perplexing plenitude of reality, the depth of his quest for clarity and truth. Milosz's poems circulate in the bloodstream not just of Polish but also of American poetry. He offered us at every stage of his development a model of poetic-of human-integrity and seriousness. One marvels at how much of the twentieth century he forced himself to confront and internalize, how much beauty he wrung from its blood-soaked precincts. So much of his work seems haunted by survivor’s guilt, the poignancy of living after what was, for so many, the world’s end. Poetry served him as an offering to the dead, a form of expiation, a hope for redemption. His first obsessive subject was the grim reality of human suffering. Yet his poems are also filled with a survivor's wonder, with a sense of astonishment that the world still exists at all, that we are here to partake of it with a profound gratitude and reverence. He was submerged, as he put it, "in everything that is common to us, the living." He looked to the earth-to being here-for salvation, and kept an eye on the eternal. Milosz's greatest poetry is written at the borders of what can be said. It makes a strong effort at expressing the unsayable. There was always in his work an element of catastrophism, a grave open-eyed lucidity about the twentieth century. His work was initiated by the apocalyptic fires of history. Milosz usefully employed the guilt so deeply ingrained in him to summon old stones, to remember those who came before him. He was weighed down by the past, fundamentally responsible to those he had outlasted, and thus bore the burden of long memory. He taught the American poet-and American poetry itself-to consider historical categories, not the idea of history vulgarized by Marxism but something deeper and more complex, more sustaining: the feeling that mankind is memory, historical memory, and that hope is in the historical." In both poetry and prose he gave us a series of Cassandra-like warnings about America's painful indifference to European experience, about the consequences of what happens when "nature becomes theater." In his splendid poetic argument with Robinson Jeffers, he countered Jeffers's praise of inhuman nature his native realm where nature exists on a human scale. Milosz modeled his own obsessive concern with our collective destiny; with he called "the riddle of Evil active in history." Like Alexsander Wat whose memory he devotedly kept alive, he was deeply aware of tragic fragmentation, but he didn't revel in that fragmentation so much as seek to transcend it. In our age of the most profound relativism, he offered an ongoing search for immutable values. He gave us a historical poetry inscribed under the sign of eternity. I love Milosz's poetry for its plenitudes and multilevel polyphonies. He taught us to love lyric poetry and also to question it. He insisted that his poems were dictated by a daimonion, and yet he also exemplified what it means to be a philosophical poet. His poetry was fueled by suffering but informed by moments of unexpected happiness. He understood the cruelty of nature and yet remembered that the earth merits our affection. He thought deeply about the rise and fall of civilizations, and he praised the simple marvels of the earth, the sky, and the sea. "There is so much death," he wrote in "Counsels," "and that is why affection / for pig-tails, bright-colored skirts in the wind, / for paper boats no more durable than we are." He wrote of the eternal moment and the holy word: Is. He reminded us how difficult it is to remain just one person. He insisted on our humanity. I love his poetry most of all for its radiant moments of wonder and being, because of its tenderness toward the human. It is a permanent gift. GIFT

A day so happy. Fog lifted early, I worked in the garden. Hummingbirds were stopping over honeysuckle flowers. There was no thing on earth I wanted to possess. I knew no one worth my envying him. Whatever evil I had suffered, I forgot. To think that once I was the same man did not embarrass me. In my body I felt no pain. When straightening up, I saw the blue sea and sails. Một ngày thật hạnh phúc Edward Hirsch: Poet’s Choice NOTES ON EXILE

He did not find happiness, for there was no happiness in his country ADAM MICKIEWICZ USAGE Exile accepted as a destiny, in the way we accept an incurable illness, should help us see through our self-delusions. PARADIGM He was aware of his task and people were waiting for his words, but he was forbidden to speak. Now where he lives he is free to speak but nobody listens and, moreover, he forgot what he had to say. COMMENTARY ON THE ABOVE Censorship may be tolerant of various avant-garde antics, since they keep writers busy and make literature an innocent pastime for a very restricted elite. But as soon as a writer shows signs of being attentive to reality, censorship clamps down. If, as a result of banishment or his own decision, he finds himself in exile, he blurts out his dammed-up feelings of anger, his observations and reflections, considering this as his duty and mission. Yet that which in his country is regarded with seriousness as a matter of life or death is of nobody's concern abroad or provokes interest for incidental reasons. Thus a writer notices that he is unable to address those who care and is able to address only those who do not care. He himself gradually becomes used to the society in which he lives, and his knowledge of everyday life in the country of his origin changes from tangible to theoretical. If he continues to deal with the same problems as before, his work will lose the directness of captured experience. Therefore he must either condemn himself to sterility or undergo a total transformation. Czeslaw Milosz: To Begin Where I Am Anh ta không tìm

thấy hạnh phúc, bởi vì làm gì có hạnh

phúc ở xứ sở của anh ta. Adam Mickiewicz. Lưu vong: Cách sử dụng Hãy coi lưu vong là

số kiếp, theo nghĩa một thứ bịnh không sao chữa lành, chỉ

có cách đó mới giúp chúng ta vứt bỏ

vào thùng rác những hoang tưởng về mình. Lưu Vong: Khuôn Mẫu Anh ta biết nhiệm vụ của mình,

và nhân dân đang chờ đợi những lời nói của anh,

nhưng anh bị cấm nói. Bây giờ, ở nơi anh đang

ở, anh tha hồ mà nói, nhưng chẳng ai thèm nghe, vả

chăng, anh quên mẹ những gì anh phải nói. Lưu vong: Thích nghi Sau nhiều năm lưu vong, chúng

mình bèn tưởng tượng đời mình như thế nào,

nếu chẳng lưu vong. Lưu Vong: Chán Chường Cú đánh đầu tiên

vào đầu một nhà văn lưu vong, đúng như Võ

Phiến đã từng cảm nhận: Nhà văn lưu vong không đem

theo được cùng với ông ta, độc giả thân thương của

mình! Như thế có nghĩa, cùng

với sự mất tích độc giả, nhìn vào những trang viết

cũ cứ như nhìn vào hư vô.. là chán chưòng,

tuyệt vọng, là sợ đếch ai còn biết đến tên ta [loss

of name], sợ thất bại, và những dằn vặt về đạo đức [moral torment].

Nhà văn lưu vong đau

khổ bởi vì anh ta lúc nào cũng phải bám vào

ý thức, thói quen tập thể. Có lẽ, anh ta, nhà

văn như thế đó, chưa hề bao giờ học đứng bằng đôi chân

của chính mình. Anh ta có thể thắng,

nhưng chỉ khi nào, trước đó, anh ta bằng lòng thua. [He may win, but not before

he agrees to lose] .... I translated the selected works of Simone Weil into Polish 1958 not because I pretended to be a "Weilian." I wrote frankly in the preface that I consider myself a Caliban, too fleshy, heavy, to take on the feathers of an Ariel. Simone Weil was an Ariel. My aim was utilitarian, in accordance, I am sure, with I wishes as to the disposition of her works. A few years ago I spent many afternoons in her family's apartment overlooking the Luxembourg Gardens-at her table covered with ink stains from I pen-talking to her mother, a wonderful woman in her eighties. Albert Camus took refuge in that apartment the day he received the Nobel Prize and was hunted by photographers and journalists. My aim, as I say, was utilitarian. I resented the division Poland into two camps: the clerical and the anticlerical, nationalistic Catholic and Marxist- I exclude of course the apparatchiki, bureaucrats just catching every wind from Moscow. I suspect un-orthodox Marxists (I use that word for lack of a better one) and non-nationalistic Catholics have very much in common, at least common interests. Simone Weil attacked the type of religion that is only a social or national conformism. She also attacked shallowness of the so-called progressives. Perhaps my intention when preparing a Polish selection of her works, was malicious. But if a theological fight is going on- as it is in Poland, especially in high schools and universities-then every weapon is good to make adversaries goggle-eyed and to show that the choice between Christianity as represented by a national religion and the official Marxist ideology is not the only choice left to us today. In the present world torn asunder by a much more serious religious crisis than appearances would permit us to guess, Catholic writers are often rejected by people who are aware of their own misery as seekers and who have a reflex of defense when they meet proud possessors of the truth. The works of Simone Weil are read by Catholics and Protestants, atheists and agnostics. She has instilled a new leaven into the life of believers and unbelievers by proving that one should not be deluded by existing divergences of opinion and that many a Christian is a pagan, many a pagan a Christian in his heart. Perhaps she lived exactly for that. Her intelligence, the precision of her style were nothing but a very high degree of attention given to the sufferings of mankind. And, as she says, "Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer." CZLESLAW MILOSZ: THE IMPORTANCE OF SIMONE WEIL She has instilled a new leaven into the life of believers and unbelievers by proving that one should not be deluded by existing divergences of opinion and that many a Christian is a pagan, many a pagan a Christian in his heart. Câu này, Miloz viết, có vẻ là cho riêng GCC, hoặc TTT:… Rằng rất nhiều 1 KyTô hữu, 1 kẻ vô thần và rất nhiều 1 kẻ vô thần, 1 tên Ky Tô, ở trong tim của hắn!

http://www.tanvien.net/Viet/A_Place_In_The_Country.html

The Genius of Robert Walser http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2000/nov/02/the-genius-of-robert-walser/ J.M. Coetzee November 2, 2000 Issue Was Walser a great writer? If one is reluctant to call him great, said Canetti, that is only because nothing could be more alien to him than greatness. In a late poem Walser wrote: I would wish it on no one to be me. Only I am capable of bearing myself. To know so much, to have seen so much, and To say nothing, just about nothing. Walser, nhà văn nhớn? Nếu có người nào đó, gọi ông ta là nhà văn nhớn, 1 cách ngần ngại, thì đó là vì cái từ “nhớn” rất ư là xa lạ với Walser, như Canetti viết. Như trong 1 bài thơ muộn của mình, Walser viết: Tớ đếch muốn thằng chó nào như tớ, hoặc nhớ đến tớ, hoặc lèm bèm về tớ, hoặc mong muốn là tớ Nhất là khi thằng khốn đó ngồi bên ly cà phê! Một mình tớ, chỉ độc nhất tớ, chịu khốn khổ vì tớ là đủ rồi Biết thật nhiều, nhòm đủ thứ, và Đếch nói gì, về bất cứ cái gì [Dịch hơi bị THNM. Nhưng quái làm sao, lại nhớ tới lời chúc SN/GCC của K!] Walser được hiểu như là 1 cái link thiếu, giữa Kleist và Kafka. “Tuy nhiên,” Susan Sontag viết, “Vào lúc Walser viết, thì đúng là Kafka [như được hậu thế hiểu], qua lăng kính của Walser. Musil, 1 đấng ái mộ khác giữa những người đương thời của Walser, lần đầu đọc Kafka, phán, ông này thuổng Walser [một trường hợp đặc dị của Walser]." Walser được ái mộ sớm sủa bởi những đấng cự phách như là Musil, Hesse, Zweig. Benjamin, và Kafka; đúng ra, Walser, trong đời của mình, được biết nhiều hơn, so với Kafka, hay Benjamin. W. G. Sebald, in his essay “Le Promeneur Solitaire,” offers the following biographical information concerning the Swiss writer Robert Walser: “Nowhere was he able to settle, never did he acquire the least thing by way of possessions. He had neither a house, nor any fixed abode, nor a single piece of furniture, and as far as clothes are concerned, at most one good suit and one less so…. He did not, I believe, even own the books that he had written.” Sebald goes on to ask, “How is one to understand an author who was so beset by shadows … who created humorous sketches from pure despair, who almost always wrote the same thing and yet never repeated himself, whose prose has the tendency to dissolve upon reading, so that only a few hours later one can barely remember the ephemeral figures, events and things of which it spoke.”

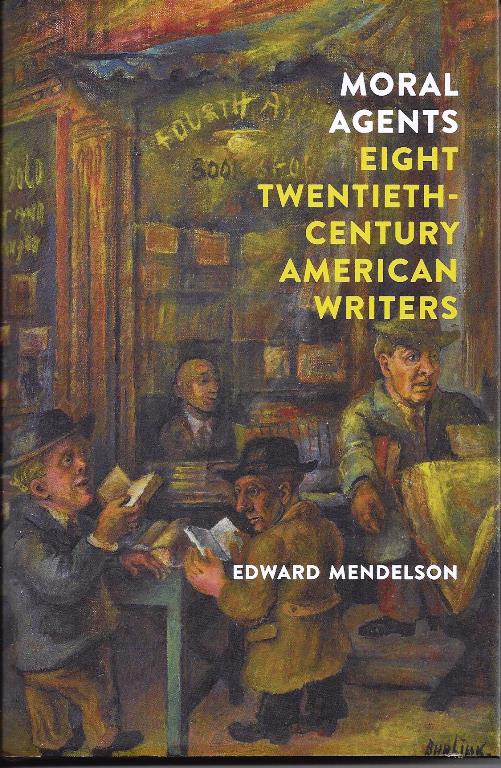

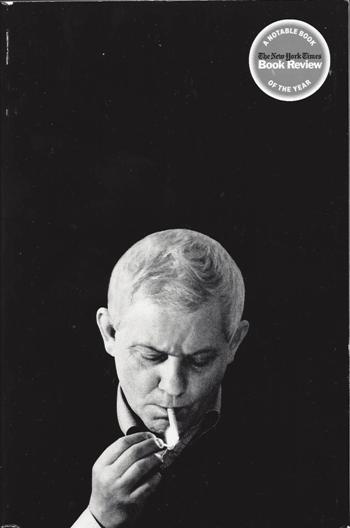

Bài viết của Coetzee về Walser, sau đưa vô “Inner Workings, essays 2000-2005”, Gấu đọc rồi, mà chẳng nhớ gì, ấy thế lại còn lầm ông với Kazin, tay này cũng bảnh lắm. Từ từ làm thịt cả hai, hà hà! Trong cuốn “Moral Agents”, 8 nhà văn Mẽo tạo nên cái gọi là văn hóa Mẽo, Edward Mendelson gọi Lionel Trilling là nhà hiền giả (sage), Alfred Kazin, kẻ bên lề (outsider), W.H, Auden, người hàng xóm (neighbor)… Bài của Coetzee về Walser, GCC mới đọc lại, không có tính essay nhiều, chỉ kể rông rài về đời Walser, nhưng mở ra bằng cái cảnh Walser trốn ra khỏi nhà thương, nằm chết trên hè đường, thật thê lương: On Christmas Day, 1956, the police of the town of Herisau in eastern Switzerland were called out: children had stumbled upon the body of a man, frozen to death, in a snowy field. Arriving at the scene, the police took photographs and had the body removed. The dead man was easily identified: Robert Walser, aged seventy-eight, missing from a local mental hospital. In his earlier years Walser had won something of a reputation, in Switzerland and even in Germany, as a writer. Some of his books were still in print; there had even been a biography of him published. During a quarter of a century in mental institutions, however, his own writing had dried up. Long country walks—like the one on which he had died—had been his main recreation. The police photographs showed an old man in overcoat and boots lying sprawled in the snow, his eyes open, his jaw slack. These photographs have been widely (and shamelessly) reproduced in the critical literature on Walser that has burgeoned since the 1960s Walser’s so-called madness, his lonely death, and the posthumously discovered cache of his secret writings were the pillars on which a legend of Walser as a scandalously neglected genius was erected. Even the sudden interest in Walser became part of the scandal. “I ask myself,” wrote the novelist Elias Canetti in 1973, “whether, among those who build their leisurely, secure, dead regular academic life on that of a writer who had lived in misery and despair, there is one who is ashamed of himself.”

|