Exile 1 Who Would Dare ? Exile 2 Ký: Bolano Ai Ðiếu: Bolano Bolano by Bomb by Playboy Scholars of Sodom |

Trang Bolano

Who Would Dare? Roberto Bolaño http://www.tanvien.net/tgtp_02/who_dare_bolano.html The books that I remember best are the ones I stole in Mexico City, between the ages of sixteen and nineteen.... Ðọc, là GNV nhớ những lần chôm sách ở 1 tiệm cho thuê truyện ở Chợ Hôm, Hà Nội.... Roberto Bolano and the visceral realists The contraband of literature: Hàng lậu văn chương http://www.tanvien.net/tgtp_02/bolano.html If we had to speculate about the characteristics of a literary movement called "visceral realism", we might assume it involved a gritty description of life. It is a forensic style, we could say, where the writer wields pen or computer cursor as a scalpel, producing literature that lies on the page like viscera on a laboratory table. In its sentences and paragraphs, we read flesh and bone, organs and blood; we see the inner workings of corporeal existence. Siddhartha Deb, trên tờ TLS số 16 Tháng Sáu, đọc Bolano [The Savage Detectives và Last Evenings on Earth], đã so sánh văn phong của ông với của những nhà "visceral realists": hiện thực lục phủ ngũ tạng. Hiện thực tim gan phèo phổi, với những đoạn văn, gồm, khúc này thì là thịt xương, khúc kia, tí phèo, tí phổi, và máu. Đây là thứ tác phẩm nội về sự hiện hữu của cơ thể, we see the inner workings of corporeal existence. Tuy nhiên, cứ coi trên đây, là diễn tả đúng, xác thực, về chủ nghĩa hiện thực lục phủ ngũ tạng, nó cũng chẳng giúp gì chúng ta nhiều, khi đọc cuốn tiểu thuyết "thất thường một cách ấn tượng, khi thì thực vui, lúc thì buồn quá", impressively manic novel, với một thứ văn phong, mặc dù làm ra vẻ "hiện thực lục phủ ngũ tạng", nhưng độc giả không thể nào tìm ra thứ nghệ thuật này ở trong 600 trang sách. Thay vì vậy, chúng ta lại được biết, về những kẻ thực hành thứ chủ nghĩa hiện thực nội tạng đó, những kẻ đã từng nắm giữ làm con tin, sinh hoạt văn học Mexico City giữa thập niên 1970. Một thứ băng đảng văn học, chứ không phải là một trào lưu, một vận động nghệ thuật. Chúng cướp đoạt, trấn lột sách vở, ăn nhậu, cãi lộn, làm tình, bán ma túy, và sau cùng biến mất, không làm sao giải thích được, và để lại, không phải một thứ văn học hiện thực nội tạng mà là những bóng ma của những gì thái quá, của thứ nghệ thuật này. Giả tưởng của Bolano, liêu trai, ma quái, ám ảnh, và có tính kinh nghiệm, experimental, nhưng không phải thứ hiện thực huyền ảo của Garcia Marquez, Carlos Fuentes, và Mario Vargas Llosa A PERFECT STORY

A while ago, at a lunch with Nicanor Parra, the poet made mention of the stories of Saki, especially one of them, "The Open Window," which is part of the book Beasts and Super Beasts. The great Saki's real name was Hector Hugh Munro and he was born in 1870 in Burma, which in those days was a British colony. His stories, heavily seasoned with black humor, generally belong to the genre of horror and supernatural fiction, so popular among the British. When World War I broke out, Saki enlisted as a volunteer, a fate he could surely have avoided by virtue of his age (he was over forty), and he died fighting at Beaumont-Hamel in 1916. During that long postprandial conversation, which lasted until nightfall, I thought about a writer of the same generation as Munro, though stylistically he was very different: the great Max Beerbohm, who was born in London in 1872 and died in Rapallo, Italy, in 1956, and who, in addition to stories, wrote novels, newspaper pieces, and essays, without ever giving up two of his first loves: drawing and caricature. Max Beerbohm may be the paradigm of the minor writer and the happy man. In other words: Max Beerbohm was a good and gracious soul. When we finally took our leave of Nicanor Parra and the Caleuche and returned to Santiago, I thought about the story that I believe is Beerbohm's best, "Enoch Soames," which was included by Silvina Ocampo, Borges, and Adolfo Bioy Casares in the magnificent and often hard to find Antologia de la literatura fantastica [Anthology of Fantastic Literature]. Months later I reread it. The story is about a mediocre and pedantic poet whom Beerbohm meets in his youth. The poet, who has written only two books, one worse than the next, befriends the young Beerbohm, who in turn becomes an involuntary witness to his misfortunes. The story thus becomes not just a testament to the life of all poor fools who in a moment of madness choose literature, but to late nineteenth-century London. Thus far, of course, it's a comic tale, vacillating between naturalism and reportage (Beerbohm appears under his real name, as does Aubrey Beardsley), between satire and the broad brushstrokes of costumbrismo. But suddenly everything changes, absolutely changes. The critical moment comes when Enoch Soames, lost in thought, glimpses his mediocrity. He's seized by despair and apathy. One afternoon Beerbohm runs into him at a restaurant. They talk, and the young narrator tries to cheer up the poet. He points out that Soames's financial situation is all right, he can live on his income for the rest of his life, maybe he just needs a holiday. The bad poet confesses that all he wants to do is kill himself and that he would give anything to know whether his name will live on. Then someone at the next table, a man with the look of a scoundrel or miscreant, asks permission to join them. He introduces himself as the Devil and he promises that if Soames sells him his soul he'll send him into the future, say one hundred years, to 1997, to the British Library Reading Room where Soames often goes to work, so he can see for himself, in situ, whether his name has stood the test of time. Despite Beerbohm's pleas, Soames accepts. Before he leaves he agrees to meet Beerbohm again at the same restaurant. The next few hours are described like something out of a dream-a nightmare-in a Borges story. When at last they meet again, Soames is as pale as death. He really has traveled to the future. He couldn't find his name in any encyclopedia, any index of English literature. But he did find the Beerbohm story called "Enoch Soames," in which, among other things, he's mocked. Then the Devil comes and takes him away to hell, despite Beerbohm's efforts to stop him. In the last lines there's still a final surprise, having to do with the people Soames claims to have seen in the future. And there's yet another surprise, this one much smaller, concerning paradoxes. But these two final surprises I'll leave to the reader who buys the Antologia de fa literatura fantdstica or who rifles through libraries in search of it. Personally, if I had to choose the fifteen best stories I've read in my life, "Enoch Soames" would be among them, and not in last place. Roberto Bolano: Between Parentheses Truyện ngắn tuyệt hảo Theo Bolano, truyện ngắn tuyệt hảo, là "Enoch Soames" của Max Beerbohm, trong cuốn truyện quái dị, do Borges & friends biên tập. Thú vị làm sao, GCC có cuốn này. Book of Fantasy http://www.tanvien.net/Sach_Moi_Xuat_Ban/Book_of_fantasy_Borges.html Naipaul on Borges

V.S. Naipaul’s essays on Argentina, “Argentina: The Brothels Behind the Graveyard,” “Comprehending Borges,” and “The Corpse at the Iron Gate,” originally appeared in The New York Review.

le Magazine Littéraire, Avril 2006 par Enrique Vila-Matas LE GRAND BOLANO Le désert comme métaphore exaspérée de l'Univers Pendant

des années et des années, le Chilien Roberto Bolano mena à

Blanes, sur la Costa Brava catalane, une vie semblable à celle de Sensini,

personnage de plusieurs de ses nouvelles: la vie d'un écrivain argentin

qui a pris de la bouteille et qui survit en envoyant ses écrits à toutes

sortes de concours littéraires espagnols de troisième catégoric. Pendant

des années et des années, l'auteur d'Appels téléphoniques

(1), qui était dans la gêne, n'eut pas le téléphone. Il vivait

isolé à Blanes avec sa femme et son fils, et son écriture avait quelque

chose de caché et de clandestin. Jusqu'au jour où, atteignant la quarantaine,

il publia aux éditions Seix Barral La Littérature nazie en Amérique,

livre qui passa relativement inapercu aux yeux de presque tout le monde,

mais pas a ceux de Jorge Herralde, directeur d'Anagrama, qui le remarqua

et, en l'absence de télephone, écrivit à son auteur une lettre qui s'interessait

à sa production. Un mois plus tard, Bolafio remettait à Herralde Étoile

distante, oeuvre que connaissent les lecteurs francais, roman écrit

en état de grace pendant trois semaines intenses de 1996, court récit dote

d'une grande énergie narrative.

Quelques mois plus tard, il avait déjà terminé un autre livre au titre peut-être ironique, Appels téléphoniques. Et deux ans plus tard, alors qu'il était encore sous les effets de son époustouflant eveil créatif, paraissait son roman Les Détectives sauvages, oeuvre torrentielle qui obtint le prix Herralde et le prix Rómulo Gallegos (la plus prestigieuse récompense de langue espagnole) et ébranla une minorité choisie de lecteurs et d'écrivains qui virent dans ce livre la fin d'une époque pendant laquelle, dans la géographie littéraire latino-américaine, avaient brillé Marelle de Cortazar et les auteurs du célèbre boom avec Garcia Marquez et Vargas Llosa en tête de file. Avec Les Détectives sauvages, les lecteurs du livre eurent l'impression de percevoir les premiers indices réels de la fin de la panoplie des coqs amazoniens, c'est-à-dire les premiers signes de la fin du voyage imprégné de couleur locale des sacro-saints auteurs du boom (parmi lesquels, bien sur, ne figurerent jamais les meilleurs; par exemple, Borges et Rulfo). Première chose. Par ailleurs, ils eurent l'impression de se trouver en face d'un auteur surprenant qui, instillant aux lecteurs la joie élementaire procurée par la passion de la lecture, s'etait installé du jour au lendemain devant un abime où personne ne l'attendait. Que faisait Bolafio à cet endroit? Écrire sur ce bord, sur ce fil après lequel il y avait le vide. Nous savons, aujourd'hui, que Les Détectives sauvages doit être considéré - avec 2666, son gigantesque roman posthume - comme l'un des deux axes majeurs de la déjà légendaire et exceptionnelle production narrative de Bolano, mort prématurement il y a trois ans. « On ne sait pas très bien comment cet homme a pu aller si loin », écrivit Eduardo Lago, pour qui Bolano était un ecrivain qui ouvrit un chemin permettant aux autres de passer. C'est surement ce que virent en lui, dès le depart, notamment dans Les Détectives sauvages, les jeunes écrivains, surtout latino-arnericains. Ce grand roman leur parlait du voyage infini de gens qui furent jeunes et désespérés, mais qui ne s'ennuyerent jamais; il leur parlait de poètes en colère de la géneration maudite de ceux qui étaient nés dans les années 1950. La nouveauté dans Les Détectives sauvages - comme a su le voir l'un de ses premiers critiques, l'Argentin Marcelo Cohen - n'était pas « le recensement du destin fangeux et brisé d'un Latino-Americain qui avait voulu briller, mais quelque chose de supérieur: la revendication des entrailles poétiques du continent ». Le livre parle d'un voyage éternel, d'une fuite infinie au cours de laquelle Arturo Belano et Ulises Lima, deux poètes visceraux, cherchent les traces perdues d'une énigrnatique pionnière de leur mouvement poétique radical, traces qui s'effacerent dans les années 1920 dans le désert mexicain de Sonora. Le désert comme métaphore exasperée de l'Univers, le lieu où tout est encore possible puisque rien n'est encore marqué, à l'exception du plus gigantesque des désespoirs .• Traduit de l'espagnol par Andre Gabastou (1) Tous les livres cités de Roberto Bolano sont parus aux éditions Bourgois, à l'exception de 2666, it paraitre. Những

nhà khoa bảng Đại Học Văn Khoa Xề Gòn

I.

Đó là năm 1972, và

tôi có thể thấy V.S Naipaul thong thả dạo phố Buenos Aires. Thong thả dạo, quả thế, nhưng đôi khi, có hẹn, dáng đi của ông vội vã, mắt nhìn cái phải nhìn, tránh phiền hà tới mức tối thiểu, và điểm hẹn thì có khi, một nơi chốn riêng tư, nhưng thuờng là 1 quán cà phê, hay 1 nhà hàng, kể từ khi mà rất nhiều người gặp ông thường khoái 1 nơi chốn công cộng, như thể họ bị mắc mớ, liên luỵ với cái tay Hồng Mao hơi có tí đặc dị này, hoặc, như thể họ bị vỡ mộng, khi chứng kiến tận mắt, tác giả bằng xương bằng thịt, của những cuốn tiểu thuyết thần sầu, nào là Phố Miguel, nào là Căn Nhà Của Me- Xừ Biswas, hoặc, ui chao "anh già" đó ư, sao chẳng giống ai, sao chẳng giống cái gã mình thường tưởng tượng ra 1 tí nào, hoặc, chẳng ai biểu tôi…

Sven Birkerts Elsewhere, taking a brash swipe at Isabel Allende, darling of Latin American literature, Bolaño writes: "Asked to choose between the frying pan and the fire, I choose Isabel Allende. The glamour of her life as a South American in California, her imitations of Garcia Marquez, her unquestionable courage, the way her writing ranges from the kitsch to the pathetic and reveals her as a kind of Latin American and politically correct version of the author of The Valley of the Dolls..." (110) I hear the hiss of that frying pan. Finally—hard to resist this—is

the very last bit from an interview Bolaño gave to Monica Maristain for the

Mexican edition of Playboy near the end of his life, while he was awaiting

a liver transplant. Maristain asks, "What would you have liked to be instead

of a writer?" Bolaño: I would much rather have

been a homicide detective than a writer. That's the one thing I'm absolutely

sure of. A homicide cop, someone who returns alone at night to the scene

of the crime and isn't afraid of ghosts. Maybe then I really would have gone

crazy, but when you're a policeman, you solve that by shooting yourself in

the mouth. "LITERATURE IS NOT MADE FROM WORDS ALONE" Tôi nghĩ, có. Hơn nữa, văn chương đâu chỉ làm bằng từ ngữ không thôi. Borges phán, có những nhà văn không thể dịch được. Tôi nghĩ ông ta coi Quevedo như là 1 thí dụ. Chúng ta có thể thêm vô Garcia Lorca và những người khác. Tuy nhiên, Don Quixote có thể cưỡng lại ngay cả những đấng dịch giả tồi tệ nhất. Như là 1 sự kiện, nó có thể cưỡng lại tùng xẻo, mất mát nhiều trang, và ngay cả một trận bão khốn kiếp. Nghĩa là, nó cưỡng lại mọi thứ ở trên đời chống lại nó - dịch dở, không đầy đủ, hay huỷ diệt - bất cứ một bản văn Don Quixote nào vẫn có nhiều điều để mà nói ra, với một độc giả Trung Hoa, hay Phi Châu. Và đó là văn chương. Chúng ta có thể mất mát rất nhiều ở dọc đường, chắc chắn như thế, nhưng đó là định mệnh của nó. Có còn hơn không, thì cứ nói như vậy có tiện việc sổ sách. Khi

đọc tôi hạnh phúc hơn rất nhiều khi viết. Với

ý này, “Bô Na Nô” đi cả 1 bài, trả lời phỏng vấn: Ðọc thì luôn quan trọng

hơn nhiều, so với viết, "Reading is always more important than writing” MORE CLUES FOR DETECTIVES

Bolano đau khổ cái số phận, còn tệ

hại cả “bị người đời rẻ rúng một cách bất công”: ông bị thổi bất công! Một

hay hai tiểu thuyết của ông là những trải nghiệm đáng nhớ, nhưng hầu hết

độc giả, tìm đọc tác phẩm vì cái chất thiên tài cách mạng mà đám đệ tử cà

chớn của ông ta hít hà, và nghĩ rằng họ đã khám phá ra ở Thầy của họ, thì

sẽ thất vọng. Một sư phụ được chọn lựa không bắt buộc tự coi mình là sư phụ,

và chúng ta có thể hy vọng là đám đệ tử này sẽ thành công, ở cái chỗ mà vị

thầy được bổ nhiệm sau khi chết này, thất bại. Bolano là 1 trong những nhà văn hiếm,

lạ, viết cho tương lai, và chúng ta, đặc biệt là cái đám thuộc thế giới tiếng

Anh, chỉ mới bắt đầu ngửi ra ông, ngửi ra cái thiên tài kỳ lạ, xiên xéo

này. Bằng nhận thức muộn, thêm vào

đó, là cái chết sớm của ông, một người đọc như chúng ta có thể nhận ra một

cái bóng u sầu, đọa đầy phủ lên tác phẩm của ông, nhưng phẩm chất đặc dị

nhất thì là 1 thứ vui nhộn, tếu tếu, chúng ta có thể tưởng tượng ra một đấng

đàn ông thung thăng tản bộ trong Thung Lũng Tử Thần, tay thọc túi quần, miệng

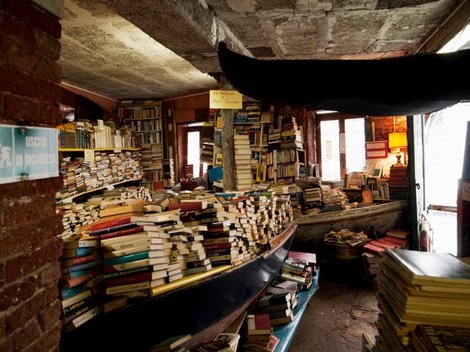

huýt sáo. HS/MB: Like Borges, you have lived through your

reading. RB: In one way or another, we're

all anchored to the book. A library is a metaphor for human beings or what's

best about human beings, the same way a concentration camp can be a metaphor

for what is worst about them. A library is total generosity. HS/MB: Nevertheless, literature is not purely

a sanctuary for good sentiment. It is also a refuge for hatefulness and resentment.

RB: I accept that. But it's indisputable

that there are good sentiments in it. I think Borges said that a good writer

is normally a good person. It must have been Borges because he said practically

everything. Good writers who are bad people are the exception. I can think

only of one. HS/MB: Who? Như Borges, ông sống qua đọc. "LITERATURE IS NOT MADE FROM WORDS ALONE" HS/MB: Is it disturbing to think we have read

many of our gods (James, Stendhal, Proust) in translation, in second-hand

versions? Is that literature? If we spin the matter around, it's possible

we might end up concluding that words don't have an equivalent. RB: I think they do. Furthermore, literature is not made from words alone. Borges says that there are untranslatable writers. I think he uses Quevedo as an example. We could add Garcia Lorca and others. Notwithstanding that, a work like Don Quijote can resist even the worst translator. As a matter of fact, it can resist mutilation, the loss of numerous pages and even a shit storm. Thus, with everything against it-bad translation, incomplete and ruined-any version of Quijote would still have very much to say to a Chinese or an African reader. And that is literature. We may lose a lot along the way. Without a doubt. But perhaps that was its destiny. Come what may. Thật

là bực mình khi nghĩ rằng chúng ta đọc rất nhiều những vị thần của chúng

ta (James, Stendhal, Proust), qua bản dịch, qua những... xái xảm? Ðó là văn

chương ư? Nếu chúng ta lèm bèm hoài về vấn đề này, liệu có thể đưa đến kết

luận: từ ngữ không có một đồng đẳng, ngang hàng?

Tưởng Niệm BolanoTôi nghĩ, có. Hơn nữa, văn chương đâu chỉ làm bằng từ ngữ không thôi. Borges phán, có những nhà văn không thể dịch được. Tôi nghĩ ông ta coi Quevedo như là 1 thí dụ. Chúng ta có thể thêm vô Garcia Lorca và những người khác. Tuy nhiên, Don Quixote có thể cưỡng lại ngay cả những đấng dịch giả tồi tệ nhất. Như là 1 sự kiện, nó có thể cưỡng lại tùng xẻo, mất mát nhiều trang, và ngay cả một trận bão khốn kiếp. Nghĩa là, nó cưỡng lại mọi thứ ở trên đời chống lại nó - dịch dở, không đầy đủ, hay huỷ diệt - bất cứ một bản văn Don Quixote nào vẫn có nhiều điều để mà nói ra, với một độc giả Trung Hoa, hay Phi Châu. Và đó là văn chương. Chúng ta có thể mất mát rất nhiều ở dọc đường, chắc chắn như thế, nhưng đó là định mệnh của nó. Có còn hơn không, thì cứ nói như vậy có tiện việc sổ sách. Roberto Bolaño, who has died

at Blanes in northern Spain of liver failure, aged 50, was one of the most

talented and surprising of a new generation of Latin American writers. Born in the Chilean capital of

Santiago, Bolaño was typical of a generation of Latin American writers who

had to cope with exile and a difficult relationship with their home country,

its values and its ways of seeking accommodation with a turbulent history.

Bolaño turned to literature to express these experiences, mixing autobiography,

a profound knowledge of literature, and a wicked sense of humour in several

novels and books of short stories that won him admirers throughout Latin

America and Spain. Bolaño spent much of his adolescence

with his parents in Mexico. He returned to Chile in 1972, to take part in

President Allende's attempts to bringing revolutionary change to the country.

Arrested for a week after the September 1973 Pinochet coup, Bolaño eventually

made his way once more to Mexico, where he embarked on his literary career.

At first he wrote poetry, strongly marked by Chilean surrealism and experimentalism,

but after moving to Spain in 1977 he turned to prose, first in short-story

form and then more ambitious novels. His mischievous spirit upset

many fellow writers, who often bore the brunt of his attacks. Fed up with

the pious sentimentalism of the kind of socially committed literature he

felt was expected of Chilean writers, he aimed to subvert good taste, revolutionary

or conservative. This iconoclasm led to books such as the History Of Nazi

Literature In Latin America, an invented genealogy of writers. In 1998, Bolaño published his

best-known work, the sprawling novel Los Detectives Salvajes (The Wild Detectives),

a challenging mixture of thriller, philosophical and literary reflections,

pastiche and autobiography, which he baptised "infrarealism". The novel won

him the Herralde and Romulo Gallegos prizes, and established Bolaño as one

of the foremost writers in the Hispanic world. English readers so far have only

been able to read By Night In Chile, published by Harvill this year. This

is the most straightforward of his books, looking back as it does to the

Pinochet days in Chile and the coexistence of evil, compromise and literature

in extreme situations. When Bolaño came to London early

this year for the English publication of By Night in Chile, he was already

very ill from a longstanding liver complaint. Despite this, he was still

talking non-stop of the many projects he was involved in, including a mammoth

novel provisionally entitled 2666, already more than 1,000 pages long, that

dealt with the murders of more than 300 young women in the Mexican border

town of Ciudad Juarez, another novel, and a new collection of poetry. But what most delighted him during

his London visit was the fact that he was already becoming better known in

Spain as a fictional character than as his "real" self. This is because he

is one of the main characters in the Spanish bestseller by Javier Cercas,

The Soldiers Of Salamis, where "Roberto Bolaño" helps the author to successfully

complete his novel. This mingling of reality and

fiction seemed to Bolaño a confirmation that life and literature are of equal

importance. As he said at the time, "You never finish reading, even if you

finish all your books, just as you never finish living, even though death

is certain." Bolaño had faced this certainty

for years, as his liver deteriorated. He died in hospital while awaiting

a liver transplant, and is survived by his wife Carolina and two children,

Alexandra and Lautaro. · Roberto Bolaño, writer, born April 28 1953; died July 15 2003. *

"A writer's

patria or country, as someone said, is his language. That sounds pretty

demagogic, but I completely agree with him..."Roberto Bolano. Francisco Goldman trích dẫn, trong bài điểm sách của nhà văn này, trên NYRB July 19, 2007. Nguyên trong bài cảm tạ khi nhận giải thưởng văn học 1999 Romulo Gallegos Prize. Đoạn văn như sau: (1) "A writer's patria or country, as someone said, is his language. That sounds pretty demagogic, but I completely agree with him.... that it's true that a writer's country isn't his language or isn't only his language.... There can be many countries, it occurs to me now, but only one passport, and obviously that passport is the quality of the writing. Which doesn't mean just to write well, because anybody can do that, but to write marvelously well, though not even that, because anybody can do that too. Then what is writing of quality? Well, what it's always been: to know how to thrust your head into the darkness, know how to leap into the void, and to understand that literature is basically a dangerous calling." Gấu tôi tin rằng, cái ông, sách xin được tự thu hồi, đã hiểu rõ câu văn trên, dù chưa từng đọc: Phẩm chất của cái việc viết là đâm đầu vào bóng đen, là lao vào chỗ trống không, là hiểu ra rằng, văn chương là một tiếng gọi nguy hiểm. * Obituary Ai Điếu Roberto Bolaño The Great Bolano Bolano vĩ đại. Francissco Goldman đọc The Savage Detectives Last Evenings on Earth Distant Star 2666 [NYRB July, 19, 2007]

Roberto Bolano & Borges I could live under a table reading Borges. Tôi có thể sống, ở bên dưới một cái bàn, và đọc Borges. My life has been infinitely more savage than Borges's. Đời tôi hẳn nhiên là hung bạo hơn đời của Borges nhiều. Mỹ châu La tinh là nơi chốn nương

thân cho đám tâm thần, the insane asylum, của Âu Châu. Có thể, thoạt đầu,

người ta nghĩ rằng, Mỹ châu La tinh sẽ là bệnh viện của Âu Châu, hay một

cái kho hạt giống của Âu châu.

Nhưng bây giờ, thì đúng là nhà thương tâm thần. Một nơi nương náu tang thương, tàn bạo, nghèo đói, hung hãn, nơi, mặc dù hỗn loạn, tham nhũng, hư ruỗng, nếu bạn mở thật lớn mắt, bạn có thể nhìn cái bóng của điện Louvre. Roberto Bolano Ui chao, đọc, và Gấu cứ nghĩ, đây là một ông đại quan VC, [hay con hay cháu ông ta, bà ta, hay bất cứ một nhà văn, nhà thơ thuộc thế hệ thứ nhì, thứ ba, sau khi lấy được Miền Nam], đi Paris du học, hoặc tham quan, hoặc tham dự hội nghị văn học, hoặc đọc thơ.... khi trở về lại Việt Nam, và phán, trong nỗi nhớ hoài một Paris mà đại quan VC vừa phải rời bỏ! Giá chuyến đi cho đủ chất liệu để chơi cả một cuốn tiểu thuyết như ông đại quan VC họ Hồ đi Ấn về, đã từng trước tác, thì thật là tuyệt! * Bolano thường được hỏi, ông có tự coi ông là nhà văn Chile, do sinh ra tại Santiago vào năm 1953, hay nhà văn Tây Ban Nha, vì đã sống ở đó hai thập niên cuối đời cho tới khi mất vào năm 2003, hay nhà văn Mễ Tây Cơ, do sống ở Mexico tuy không thường trực, nhưng cũng đực cái, chừng 10 năm, và ông trả lời, có lần, tôi là nhà văn Mỹ La Tinh, Latin American. Những lần khác, ông nói, ngôn ngữ Tây Ban Nha là nhà của tôi. * Những nguy hiểm không thể nào tách rời của đời sống và văn chương, và những liên hệ của đời sống vào văn chương, là những đề tài liên luỷ của những gì ông viết ra, và cũng còn là của cuộc đời ông. như ông hách xì xằng, và thật thách đố, chọn sống như thế. Cuối đời nhìn lại, ông có ba tuyển tập, và 10 cuốn tiểu thuyết. Cuốn tiểu thuyết cuối cùng, 2666, chưa hoàn tất, khi ông mất vì bịnh gan, vào năm 2003, vậy mà không ngăn được những nhà phê bình, khi coi đây là một đại tác phẩm. * Roberto Bolano and the visceral realists

If we had to speculate about the characteristics of a literary movement

called "visceral realism", we might assume it involved a gritty description

of life. It is a forensic style, we could say, where the writer wields pen

or computer cursor as a scalpel, producing literature that lies on the page

like viscera on a laboratory table. In its sentences and paragraphs, we read

flesh and bone, organs and blood; we see the inner workings of corporeal

existence.The contraband of literature: Hàng lậu văn chương Siddhartha Deb, trên tờ TLS số 16 Tháng Sáu, đọc Bolano [The Savage Detectives và Last Evenings on Earth], đã so sánh văn phong của ông với của những nhà "visceral realists": hiện thực lục phủ ngũ tạng. Hiện thực tim gan phèo phổi, với những đoạn văn, gồm, khúc này thì là thịt xương, khúc kia, tí phèo, tí phổi, và máu. Đây là thứ tác phẩm nội về sự hiện hữu của cơ thể, we see the inner workings of corporeal existence. Tuy nhiên, cứ coi trên đây, là diễn tả đúng, xác thực, về chủ nghĩa hiện thực lục phủ ngũ tạng, nó cũng chẳng giúp gì chúng ta nhiều, khi đọc cuốn tiểu thuyết "thất thường một cách ấn tượng, khi thì thực vui, lúc thì buồn quá", impressively manic novel, với một thứ văn phong, mặc dù làm ra vẻ "hiện thực lục phủ ngũ tạng", nhưng độc giả không thể nào tìm ra thứ nghệ thuật này ở trong 600 trang sách. Thay vì vậy, chúng ta lại được biết, về những kẻ thực hành thứ chủ nghĩa hiện thực nội tạng đó, những kẻ đã từng nắm giữ làm con tin, sinh hoạt văn học Mexico City giữa thập niên 1970. Một thứ băng đảng văn học, chứ không phải là một trào lưu, một vận động nghệ thuật. Chúng cướp đoạt, trấn lột sách vở, ăn nhậu, cãi lộn, làm tình, bán ma túy, và sau cùng biến mất, không làm sao giải thích được, và để lại, không phải một thứ văn học hiện thực nội tạng mà là những bóng ma của những gì thái quá, của thứ nghệ thuật này. Giả tưởng của Bolano, liêu trai, ma quái, ám ảnh, và có tính kinh nghiệm, experimental, nhưng không phải thứ hiện thực huyền ảo của Garcia Marquez, Carlos Fuentes, và Mario Vargas Llosa.

Roberto Bolaño The books that I remember best are the ones I stole

in Mexico City, between the ages of sixteen and nineteen.... Tính dịch bài này, nhân tiện đi một đường thú tội trước bàn thờ nhưng bạn NL đã nhanh tay lẹ chân hơn. Thế là lại cất cái vụ thú tội đi, để khi nào rảnh vậy! Bản tiếng Việt của NL. Post ở đây, để kiểm tra coi,

loạn hay không loạn! Những quyển sách tôi còn nhớ

rõ nhất là những quyển tôi ăn cắp ở Mexico City, từ tuổi mười sáu đến tuổi

mười chín, cùng những quyển tôi mua ở Chilê khi tôi hai mươi, trong những

tháng đầu tiên của cuộc đảo chính. Tại Mexico hồi ấy có một hiệu sách choáng

lắm. Nó tên là Hiệu Sách Kính, nằm trên phố Alameda. Tường, rồi cả trần nữa,

đều bằng kính cả. Kính và rầm sắt. Nhìn từ ngoài, trông nó như là một nơi

không thể ăn cắp được. Thế nhưng sự thận trọng chẳng là gì so với cám dỗ

thử thách và sau một thời gian thì tôi bắt đầu thử xem sao. Quyển sách đầu tiên rơi vào tay

tôi là một tập sách mỏng của Pierre Louÿs [nhà thơ huê tình thế kỷ XIX], có

những trang giấy mỏng như giấy Kinh Thánh, giờ thì tôi không nhớ nổi là tập

Aphrodite hay tập Les Chansons de Bil trở thành người hướng lối cho tôi.

Rồi tôi trộm sách của Max Beerbohm (The Happy Hypocrite), Champfleury,

Samuel Pepys, anh em Goncourt, Alphonse Daudet, của Rulfo và Arreola, các

nhà văn Mexico hồi ấy vẫn còn viết ít nhiều, những người hẳn tôi từng gặp

vào buổi sáng nào đó trên Avenida Niño Perdido, một phố đông chật người

mà ngày nay tôi không sao tìm lại được trên các bản đồ Mexico City nữa,

cứ như thể Niño Perdido chỉ có thể tồn tại trong trí tưởng tượng của tôi,

hoặc giả cái phố ấy, với những cửa hàng ngầm dưới đất và những người trình

diễn trên đường đã thực sự lạc mất, giống y như tôi từng lạc lối ở tuổi

mười sáu. Từ sương mù của những năm tháng

đó, từ những vụ đột kích trộm cắp đó, tôi còn nhớ nhiều tập thơ. Của Amado

Nervo, Alfonso Reyes, Renato Leduc, Gilberto Owen, Heruta và Tablada, rồi

các nhà thơ Mỹ, chẳng hạn General William Booth Enters Into Heaven, của Vachel

Lindsay vĩ đại. Nhưng cứu tôi khỏi địa ngục và chỉnh đốn tôi trở lại nghiêm

chỉnh lại là một tiểu thuyết. Cuốn tiểu thuyết ấy là Sa đọa của Camus, và

mọi thứ liên quan đến nó tôi còn nhớ như thể bị đông cứng lại trong một

ánh sáng ma quái, ánh sáng tĩnh của buổi tối, mặc dù tôi đã đọc nó, ngốn

ngấu nó trong ánh sáng của những buổi sáng đặc biệt của Mexico City, cái

ánh sáng chiếu tỏa - hoặc từng chiếu tỏa - bằng sự huy hoàng đỏ và xanh

lục trộn lẫn tiếng ồn, trên một cái ghế băng trên Alameda, không tiền tiêu

và cả một ngày trước mặt, mà thật ra thì là cả cuộc đời trước mặt. Sau Camus,

mọi thứ đã thay đổi. Tôi còn nhớ bản in đó: một quyển sách in chữ rất to, như là cho học sinh tiểu học, mảnh, bọc vải, bìa ngoài in một hình vẽ đáng sợ, quyển sách rất khó ăn trộm, tôi không biết nên kẹp nó dưới nách hay nhét vào thắt lưng, vì nó cộm lên bên dưới cái áo đồng phục học sinh trốn học của tôi, và rốt cuộc tôi đã cầm nó ra ngay dưới cái nhìn của mọi nhân viên Hiệu Sách Kính, đó là cách ăn cắp tốt nhất, mà tôi học được từ một truyện ngắn của Edgar Allan Poe. Sau đó, sau khi trộm quyển sách rồi đọc nó, tôi chuyển từ một độc giả thận trọng sang thành một độc giả phàm ăn và từ một tay trộm sách sang một tay bắt cóc sách. Tôi muốn đọc mọi thứ, trong sự ngây thơ của mình tôi cứ ngỡ như vậy là tương đương với việc muốn lật ra hay thử lật ra những cơ cấu tình cờ bị che giấu đã dẫn nhân vật của Camus tới chỗ chấp nhận số phận tồi tệ của mình. Mặc cho mọi thứ có thể dự đoán, sự nghiệp bắt cóc sách của tôi kéo rất dài và đầy thành quả, nhưng đến một ngày thì tôi bị tóm. Thật may vì không phải tại Hiệu Sách Kính, mà là Hiệu Sách Hầm, nó nằm - từng nằm - bên kia Alameda, trên Avenida Juárez, là nơi, như cái tên của nó đã chỉ rõ, giống như một cái hầm lớn chất hàng đống sách mới nhất từ Buenos Aires và Barcelona trên những cái giá bóng loáng. Vụ bắt giữ tôi thật là đáng tởm. Cứ như thể các samurai của những hiệu sách đã ra giá cho cái đầu của tôi. Bọn họ dọa đuổi tôi ra khỏi đất nước, dần cho tôi một trận nhừ tử trong hầm Hiệu Sách Hầm, điều này với tôi nghe chẳng khác gì một cuộc tranh luận giữa các triết gia mới về sự phá hủy sự phá hủy, và rồi rốt cuộc, sau những suy tính dài lâu, họ để tôi đi, nhưng trước đó đã tịch thu mọi quyển sách tôi có trên người, trong đó có Sa đọa, mà trong số đấy có quyển nào tôi ăn cắp ở chỗ họ đâu. Không lâu sau đó tôi về Chilê.

Nếu ở Mexico tôi rơi trúng vào Rulfo và Arreola thì tại Chilê tình hình tương

tự với Nicanor Parra và Enrique Lihn, nhưng tôi nghĩa nhà văn duy nhất mà

tôi từng nhìn thấy là Rodrigo Lira, khi ông bước đi thật vội vã vào một

cái đêm phảng phất mùi khí ga. Rồi xảy tới vụ đảo chính, sau đó tôi bỏ thời

gian thăm viếng các hiệu sách ở Santiago, lấy đó làm một phương cách rẻ

tiền để tiêu hủy buồn chán và điên rồ. Không giống những hiệu sách Mexico,

các hiệu sách ở Santiago không có nhân viên, mà chỉ có một người duy nhất,

gần như lúc nào cũng đồng thời là ông chủ luôn. Tại đó tôi đã mua Obra gruesa

[Toàn tập] và Artefactos của Nicanor Parra, rồi các sách của Enrique Lihn

và Jorge Teillier mà tôi sẽ nhanh chóng đánh mất, chúng là những sự đọc

cốt yếu với tôi; mặc dù “cốt yếu” chưa phải từ chuẩn: những cuốn sách ấy

giúp tôi thở. Nhưng “thở” vẫn chưa phải từ chuẩn. Cái tôi nhớ nhất ở những chuyến thăm hiệu sách là mắt những người bán sách, đôi khi trông cứ như là mắt một người bị treo cổ và đôi khi lại bị che lên một kiểu màng cơn ngủ, mà giờ đây tôi đã biết là một cái khác. Tôi không nhớ mình từng bao giờ nhìn thấy những hiệu sách cô độc hơn không. Tôi không ăn cắp quyển sách nào ở Santiago. Chúng rất rẻ nên tôi mua chúng. Tại hiệu sách cuối cùng mà tôi đến, tôi đang ngó dọc một hàng tiểu thuyết Pháp cổ thì người bán hàng, một người đàn ông cao, gầy trạc tứ tuần, đột nhiên hỏi tôi có nghĩ là đúng hay không khi một tác giả tự giới thiệu tác phẩm của mình cho một người đã bị kết án tử hình. Người bán hàng đứng ở một góc

nhà, mặc một cái áo sơ mi trắng tay áo vén lên đến khuỷu, cái yết hầu nhô

hẳn ra cứ nhúc nhắc khi ông ta nói. Tôi đáp có vẻ không được đúng đắn cho

lắm. Mà ta đang nói đến những người bị kết án nào đây? Tôi hỏi. Người bán

hàng nhìn tôi mà nói ông biết một số, hoặc hơn một, tiểu thuyết gia có khả

năng tự giới thiệu sách của mình cho một người đang ở bờ vực cái chết. Rồi

ông bảo chúng ta đang nói tới các độc giả tuyệt vọng. Tôi thì tôi không

đủ sức đánh giá đâu, ông nói, nhưng nếu không phải tôi, thì chẳng ai khác

làm được cả. Anh sẽ giới thiệu cuốn sách nào

cho một người bị kết án? ông hỏi tôi. Tôi không biết, tôi đáp. Tôi cũng không

biết, người bán hàng nói, và tôi nghĩ chuyện ấy kinh khủng lắm. Những người

tuyệt vọng thì đọc sách gì? Họ thích những sách gì? Anh hình dung như thế

nào về phòng đọc sách của một người bị kết án? ông hỏi. Tôi chẳng biết, tôi

đáp. Anh còn trẻ, tôi không thấy ngạc nhiên, ông bảo. Rồi: giống Nam Cực

ấy. Không giống Bắc Cực, mà giống Nam Cực. Tôi nhớ đến những ngày cuối cùng

của Arthur Gordon Pym [của Edgar Allan Poe], nhưng quyết định không nói

gì. Để xem nào, người bán hàng nói, con người can đảm nào dám đặt quyển tiểu

thuyết này vào lòng một người bị kết án tử hình đây? Ông rút ra một quyển

sách khá là thích hợp rồi đặt nó lên một chồng sách. Tôi trả tiền rồi đi

khỏi. Khi tôi đi khỏi, người bán hàng hẳn đã cười hoặc khóc thổn thức. Khi

bước chân ra tôi nghe thấy ông nói: Thằng khốn cao ngạo nào dám làm điều đó

cơ chứ? Rồi ông còn nói gì đó nữa, nhưng tôi không nghe ra. The books that I remember best are

the ones I stole in Mexico City, between the ages of sixteen and nineteen,

and the ones I bought in Chile when I was twenty, during the first few months

of the coup. In Mexico there was an incredible bookstore. It was called the

Glass Bookstore and it was on the Alameda. Its walls, even the ceiling, were

glass. Glass and iron beams. From the outside, it seemed an impossible place

to steal from. And yet prudence was overcome by the temptation to try and

after a while I made the attempt. The first book to fall into my hands

was a small volume by [the nineteenth century erotic poet] Pierre Louÿs,

with pages as thin as Bible paper, I can’t remember now whether it was Aphrodite

or Songs of Bilitis. I know that I was sixteen and that for a while Louÿs

became my guide. Then I stole books by Max Beerbohm (The Happy Hypocrite),

Champfleury, Samuel Pepys, the Goncourt brothers, Alphonse Daudet, and Rulfo

and Areola, Mexican writers who at the time were still more or less practicing,

and whom I might therefore meet some morning on Avenida Niño Perdido, a

teeming street that my maps of Mexico City hide from me today, as if Niño

Perdido could only have existed in my imagination, or as if the street, with

its underground stores and street performers had really been lost, just

as I got lost at the age of sixteen. From the mists of that era, from those

stealthy assaults, I remember many books of poetry. Books by Amado Nervo,

Alfonso Reyes, Renato Leduc, Gilberto Owen, Heruta and Tablada, and by American

poets, like General William Booth Enters Into Heaven, by the great Vachel

Lindsay. But it was a novel that saved me from hell and plummeted me straight

back down again. The novel was The Fall, by Camus, and everything that has

to do with it I remember as if frozen in a ghostly light, the still light

of evening, although I read it, devoured it, by the light of those exceptional

Mexico City mornings that shine—or shone—with a red and green radiance ringed

by noise, on a bench in the Alameda, with no money and the whole day ahead

of me, in fact my whole life ahead of me. After Camus, everything changed.

I remember the edition: it was a book

with very large print, like a primary school reader, slim, cloth-covered,

with a horrendous drawing on the jacket, a hard book to steal and one that

I didn’t know whether to hide under my arm or in my belt, because it showed

under my truant student blazer, and in the end I carried it out in plain

sight of all the clerks at the Glass Bookstore, which is one of the best ways

to steal and which I had learned from an Edgar Allan Poe story. After that, after I stole that book

and read it, I went from being a prudent reader to being a voracious reader

and from being a book thief to being a book hijacker. I wanted to read everything,

which in my innocence was the same as wanting to uncover or trying to uncover

the hidden workings of chance that had induced Camus’s character to accept

his hideous fate. Despite what might have been predicted, my career as a

book hijacker was long and fruitful, but one day I was caught. Luckily,

it wasn’t at the Glass Bookstore but at the Cellar Bookstore, which is—or

was—across from the Alameda, on Avenida Juárez, and which, as its name indicates,

was a big cellar where the latest books from Buenos Aires and Barcelona

sat piled in gleaming stacks. My arrest was ignominious. It was as if the

bookstore samurais had put a price on my head. They threatened to have me

thrown out of the country, to give me a beating in the cellar of the Cellar

Bookstore, which to me sounded like a discussion among neo-philosophers

about the destruction of destruction, and in the end, after lengthy deliberations,

they let me go, though not before confiscating all the books I had on me,

among them The Fall, none of which I’d stolen there. Soon afterwards I left for Chile.

If in Mexico I might have bumped into Rulfo and Arreola, in Chile the same

was true of Nicanor Parra and Enrique Lihn, but I think the only writer I

saw was Rodrigo Lira, walking fast on a night that smelled of tear gas.

Then came the coup and after that I spent my time visiting the bookstores

of Santiago as a cheap way of staving off boredom and madness. Unlike the

Mexican bookstores, the bookstores of Santiago had no clerks and were run

by a single person, almost always the owner. There I bought Nicanor Parra’s

Obra gruesa [Complete Works] and the Artefactos, and books by Enrique Lihn

and Jorge Teillier that I would soon lose and that were essential reading

for me; although essential isn’t the word: those books helped me breathe.

But breathe isn’t the right word either. What I remember best about my visits

to those bookstores are the eyes of the booksellers, which sometimes looked

like the eyes of a hanged man and sometimes were veiled by a kind of film

of sleep, which I now know was something else. I don’t remember ever seeing

lonelier bookstores. I didn’t steal any books in Santiago. They were cheap

and I bought them. At the last bookstore I visited, as I was going through

a row of old French novels, the bookseller, a tall, thin man of about forty,

suddenly asked whether I thought it was right for an author to recommend

his own works to a man who’s been sentenced to death. The bookseller was standing in a corner,

wearing a white shirt with the sleeves rolled up to the elbows and he had

a prominent Adam’s apple that quivered as he spoke. I said it didn’t seem

right. What condemned men are we talking about? I asked. The bookseller

looked at me and said that he knew for certain of more than one novelist capable

of recommending his own books to a man on the verge of death. Then he said

that we were talking about desperate readers. I’m hardly qualified to judge,

he said, but if I don’t, no one will. What book would you give to a condemned

man? he asked me. I don’t know, I said. I don’t know either, said the bookseller,

and I think it’s terrible. What books do desperate men read? What books do

they like? How do you imagine the reading room of a condemned man? he asked.

I have no idea, I said. You’re young, I’m not surprised, he said. And then:

it’s like Antarctica. Not like the North Pole, but like Antarctica. I was

reminded of the last days of [Edgar Allan Poe’s] Arthur Gordon Pym, but

I decided not to say anything. Let’s see, said the bookseller, what brave

man would drop this novel on the lap of a man sentenced to death? He picked

up a book that had done fairly well and then he tossed it on a pile. I paid

him and left. When I turned to leave, the bookseller might have laughed or

sobbed. As I stepped out I heard him say: What kind of arrogant bastard

would dare to do such a thing? And then he said something else, but I couldn’t

hear what it was. This essay is drawn from Between Parentheses:

Essays, Articles and Speeches (1998–2003) by Roberto Bolaño, translated

by Natasha Wimmer, forthcoming from New Directions on May 30.

March 22, 2011 12:15 p.m. |