Mùa

thu, những di dân

Di

dân là "số" phần, (a matter of arithmetic),

theo Kundera.

Độc và Đẹp

Thu 2014

L'adieu

Apollinaire (1880-1918)

J'ai cueilli ce brin de bruyère

L'automne est morte souviens-t'en

Nous ne nous verrons plus sur terre

Odeur du temps brin de bruyère

Et souviens-toi que je t'attends

Lời vĩnh biệt

(1)

Ta đã hái nhành lá cây

thạch thảo

Em nhớ cho, mùa thu đã chết rồi

Chúng ta sẽ không tao phùng được

nữa

Mộng trùng lai không có ở trên

đời

Hương thời gian mùi thạch thảo bốc hơi

Và nhớ nhé ta đợi chờ em đó ...

(2)

Ðã hái nhành kia một buổi nào

Ngậm ngùi thạch thảo chết từ bao

Thu còn sống sót đâu chăng nữa

Người sẽ xa nhau suốt điệu chào

Anh nhớ em quên và em cũng

Quên rồi khoảnh khắc rộng xuân xanh

Thời gian đất nhạt mờ năm tháng

Tuế nguyệt hoa đà nhị hoán tam

(3)

Mùa thu chiết liễu nhớ chăng em ?

Ðã chết xuân xanh suốt bóng

thềm

Ðất lạnh qui hồi thôi hết dịp

Chờ nhau trong Vĩnh Viễn Nguôi Quên

Thấp thoáng thiều quang mỏng mảnh dường

Nhành hoang thạch thảo ngậm mùi vương

Chờ nhau chín kiếp tam sinh tại

Thạch thượng khuê đầu nguyệt diểu mang

Xa nhau trùng điệp quan san

Một lần ly biệt nhuộm vàng cỏ cây

Mùi hương tuế nguyệt bên ngày

Phù du như mộng liễu dài như mơ

Nét mi sầu tỏa hai bờ

Ai về cố quận ai ngờ ai đi

Tôi hồi tưởng lại thanh kỳ

Tuổi thơ giọt nước lương thì ngủ yên

Bùi Giáng (1925-1998) dịch

(Ði vào cõi thơ, tr 80-82, Ca Dao

xuất bản, Sàigon, Việt Nam)

Nguồn net

GUILLAME APOLLINAIRE

(1880-1918)

The Farewell

I picked this fragile sprig of heather

Autumn has died long since remember

Never again shall we see one another

Odor of time sprig of heather

Remember I await our time together

Translated from the French by Roger Shattuck

[in Time of Grief]

Thơ Mỗi Ngày

HAIKU

The endless night

is now nothing more

than a scent.

Is it or isn't it

the dream I forgot

before dawn?

The sword at rest

dreams of its battles.

My dream is something else.

The man has died.

His beard doesn't know.

His nails keep growing.

Under the moon

the lengthening shadow

is all one shadow .

•

The old hand

goes on setting down lines

for oblivion.

-S.K.

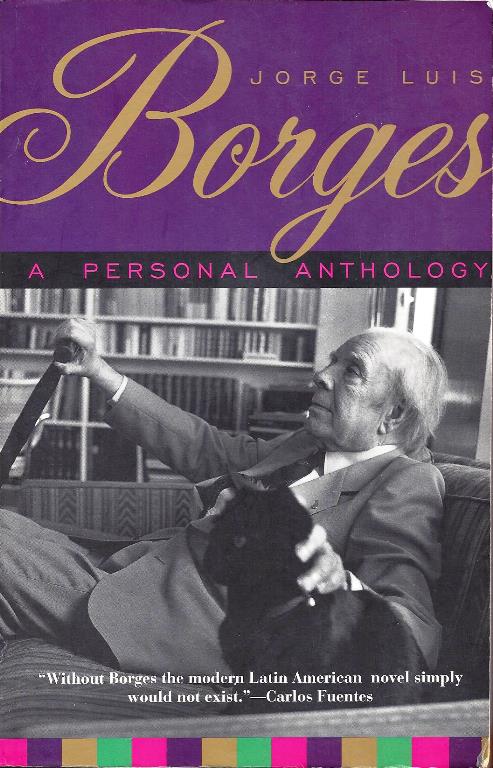

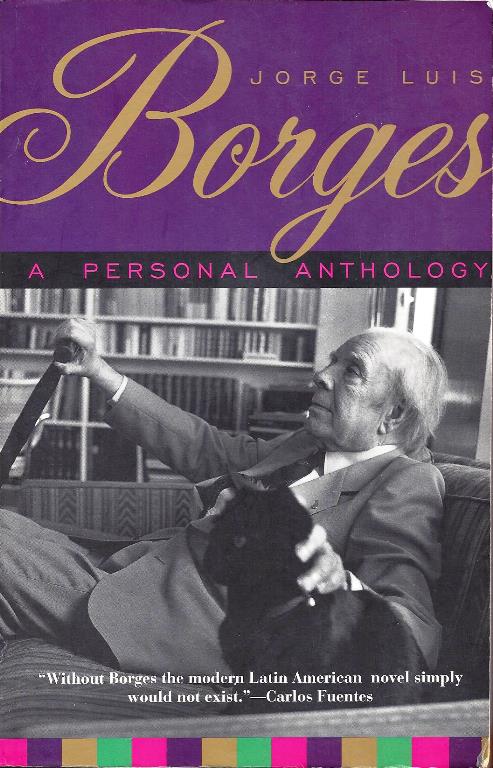

J.J. Borges: Poems of the Night

Haiku

Đêm vô tận

Còn chăng,

Thì là một mùi

Cái gì gì, tàn hôn lên

môi

Tàn quên trong tay

Có, hay không

Giấc mộng Gấu quên

Trước rạng đông

Cái gì gì, đêm không sao

qua

Mà trời sao lại sáng?

Cây kiếm ngơi

Mơ hoài những trận chém giết cũ

Giấc mơ của Gấu

Là một điều gì khác

Thẳng chả ngỏm

Râu đếch biết

Móng tay dài mãi ra

Dưới ánh trăng

Cái bóng của Gấu

Dài mãi ra

Vẫn chỉ là bóng của Gấu!

Bàn tay già

Tiếp tục lần

Những dòng

Dành cho quên lãng

Borges Golem

THE GIFT

In a page of Pliny we read

that in all the world no two faces are alike.

A woman gave a blind man

the image of her face,

without a doubt unique.

She chose the photo among many;

rejected all but one and got it right.

The act had meaning for her

as it does for him.

She knew he could not see her gift

and knew it was a present.

An invisible gift is an act of magic.

To give a blind man an image

is to give something so tenuous it can be infinite

something so vague it can be the universe.

The useless hand touches

and does not recognize

the unreachable face.

J. L. Borges: Poems of the Night

Quà

tặng

Trong một trang của Pliny, chúng

ta đọc thấy điều này,

Trong cả 1 lũ người như thế đó, không làm

sao có hai khuôn mặt giống nhau y chang

Một người đàn bà cho 1 anh mù bức hình

khuôn mặt bà.

Bà chọn tấm hình trong rất nhiều;

vứt đi tất cả, chỉ giữ lại một, và chọn đúng

tấm cần chọn.

Cái hành động đó, thì thật có

nghĩa, đối với bà

Và luôn cả với người đàn ông mù.

Bà biết anh mù không thể nhìn

thấy quà tặng của bà

Và biết, đó là 1 quà tặng

Một món quà vô hình là

1 hành động huyền diệu

Cho 1 người mù một hình ảnh

Thì cũng như cho một điều gì tinh tế, giản

dị, như “cúi xuống là đất”, như Cô Tư phán.

Chính vì thế mà nó trở thành

vô cùng

Một điều gì đó mơ hồ như là vũ trụ

Bàn tay vô dụng, sờ

Và không nhận ra

Khuôn mặt không làm sao với tới được.

PARADISO XXXI, 108

Diodorus Siculus narrates the story of a dismembered

and sundered god, who, as he walks in the twilight or traces

a date in his past, never senses that something infinite has been

lost.

Mankind has lost a face, an

irretrievable face, and everyone would like to be that pilgrim

(dreamed of in the empyrean, under the Rose) who sees Veronica's

handkerchief in Rome and murmurs with faith: Jesus

Christ, My Lord, True God, this, then, was Your Face?

There is a stone face on a

certain road and an inscription which reads: The true Portrait

of the Holy Face of the God of Jaén, If we really knew the likeness,

we would have the key to the parables and would know if the

son of the carpenter was also the Son of God.

Paul saw it in the guise of

a light which hurled him to the ground; John, as the sun shining

in full force; Teresa of Jesus, oftentimes, as if bathed in a tranquil

light, but she was never able to specify the color of the eyes.

We lost those features, in

the way a magical number may be lost, a number made up of customary

figures; in the same way as an image in a kaleidoscope is lost

forever. We may see them, and not know it. The profile of a Jew in

the subway may be that of Christ; the hands which give us some coins

at a change-window may recall those which some soldiers once nailed to

the Cross.

Perhaps some feature of the

Crucified Face lurks in every mirror; perhaps the Face died,

was effaced, so that God might become everyone.

Who knows whether we may not

see it tonight in the labyrinths of dreams and remember nothing

tomorrow.

- Translated by ANTHONY KERRIGAN

Diodorus Siculus tells the

story of a god who had been cut into pieces and then scattered;

which of us, strolling at dusk or recollecting a day from the past,

has never felt that something of infinite importance has been lost?

Mankind has lost a face, an

irretrievable face. At one time everyone wanted to be the pilgrim

who was dreamed up in the Empyrean under the sign of the Rose,

the one who sees the Veronica in Rome and fervently mutters: "Christ

Jesus, my God, truly God: so this is what your face was like?"

There is a stone face by a

road and an inscription that reads: ''Authentic Portrait of the

Holy Face of the Christ of Jaén," If we really knew what that

face had been like, we would possess the key to the parables and

we would know whether the son of the carpenter was also the Son of God.

Paul saw it as a light that

knocked him to the ground. John saw it as the sun shining with

all its strength. Teresa of Avila often saw it bathed in a serene

light, but she could never quite make out the color of the eyes.

These features have been lost

to us the way a kaleidoscope design is lost forever, or a magic

number composed of everyday figures. We can be looking at them

and still not know them. The profile of a Jewish man in the subway

may well be the same as Christ's; the hands that make change for

us at the ticket window could be identical to the hands that soldiers

one day nailed to the cross.

Some feature of the crucified

face may lurk in every mirror. Maybe the face died and faded

away so that God could be everyman.

Who knows? We might see it tonight in the labyrinths

of sleep and remember nothing in the morning.

-K.K.

Penguin ed

Diodorus Siculus kể câu

chuyện một vị thần bị chém, chặt, xẻ thành từng mẩu

rồi quăng tứ lung tung, ai trong số chúng ta, lang thang trong

hoàng hôn, hay, lượm lặt một ngày từ quá

khứ, chẳng hề cảm nhận rằng thì là, một điều cực kỳ thiên thu bất diệt, cực kỳ quan

trọng, đã

mất?

Nhân loại mất mẹ cái bộ mặt, một bộ mặt không

làm sao thu gom, nhặt nhạnh lại được, và, mọi người,

người người, ai cũng thèm là vị hành giả kia,

mơ hoài một Thiên Cung, dưới dấu hiệu BHD, kẻ đã

từng chiêm ngưỡng cái khăn tay của Thánh Nữ, một

bữa ở… Chợ Lớn, và lẩm bẩm, với Niềm Tin: Thánh Nữ

ơi, phải chăng, đây đúng là Khuôn Mặt của Người?

Đó là khuôn mặt của một hòn

đá bên vệ đường, và một hàng chữ, Khuôn

mặt thực của Chúa Jaén. Nếu chúng ta thực sự

hiểu ra sự tương đồng, tương ứng, chúng ta sẽ có được cái

chìa khoá của ẩn ngữ, và chúng ta, biết,

đấng con trai, là con của ông thợ mộc, hay là

Con của Chúa.

Paul chứng kiến phép lạ, và nó quất

cho anh đánh rầm 1 phát xuống mặt đất. John nhìn

thấy nó, như là 1 cú mặt trời với tất cả sức mạnh

của nó. Teresa of Avila thường nhìn

thấy nó, tắm trong 1 thứ ánh sáng thanh thản,

nhưng bà không làm sao nhận ra màu của mắt.

Những cảnh tượng này, đã mất đối với chúng

ta, theo cái cách mà kính vạn hoa vĩnh

viễn mất, hay con số thần kỳ gồm những hình tượng mọi

ngày. Chúng ta có thể nhìn, nhưng đâu

thấy, chúng. Cái bóng dáng của 1 tên

Mít đang lang thang 1 ngày đẹp trời ở 1 thành phố

Canada, hay đang chờ xe điện ngầm ở 1 subway station ở Toronto, thí

dụ, biết đâu đấy, thì cũng là bóng của Christ,

và cái bàn tay đang đưa cái vé xe

điện ngầm ở quầy, biết đâu đấy, là 1 trong những bàn

tay của 1 tên VC đóng đinh Chúa.

Một cảnh sắc nào đó, của khuôn mặt

bị đóng đinh thập giá, có thể lấp ló trong

mọi tấm gương.

Có thể bộ mặt chết, và nhạt nhòa

trong mưa, theo dòng thời gian và nếu thế, Chúa

có thể là bất cứ một người, mọi người.

Who knows?

GCC có thể thấy nó, đêm nay, trong

những mê cung của giấc ngủ, và sáng mai, mải

nhớ BHD,

bèn quên mẹ

nó mất!

Legend

Cain and Abel came upon each other after Abel's death.

They were through the desert, and they recognized each other from

afar, since men were very tall. The two brothers sat on the ground,

made a fire, and ate. They sat silently, as weary people do when dusk

begins to fall. In the sky, a star glimmered, though it had not yet been

given a name. In the light of fire, Cain saw that Abel's forehead bore

the mark of the stone, and dropped the bread he was about to carry to

his mouth and asked his brother to forgive him. "Was it you that killed

me, or did I kill you?" Abel answered. "I don't remember anymore; here

we are, together, like before."

"Now I know that you have truly forgiven me;' Cain said,

"because forgetting is forgiving. I, too, will try to forget."

"Yes;' said Abel slowly. “So long as remorse lasts,

guilt lasts."

Penguin ed

Note: Tình cờ lướt net,

thấy đã được dịch:

http://www.tienve.org/home/activities/viewTopics.do?action=viewArtwork&artworkId=1035

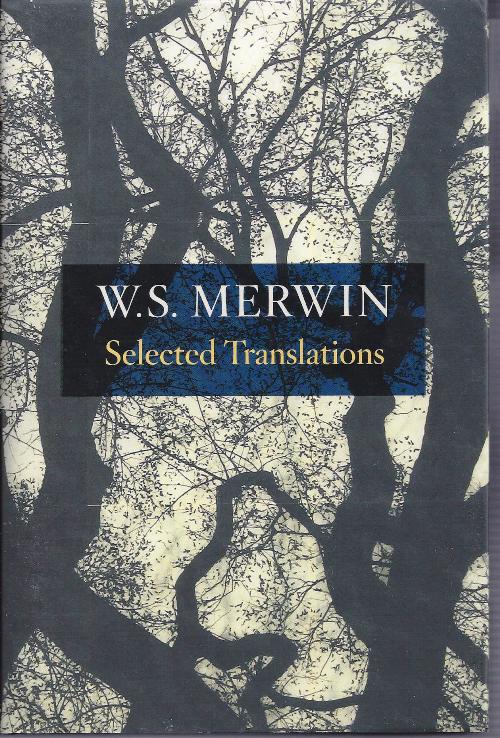

Iosip Brodsky

Russian

1940-1996

THE BLIND MUSICIANS

The blind go their way

by night.

It's

easier to cross

the

squares

at night.

The

blind live

feeling

their way,

brushing

the world with their hands,

knowing

neither shadow nor light,

and

their hands drift over the stones

built

into walls

of

men, women,

children,

money,

walls

that cannot be broken,

better

to

follow along them.

Against

them the music

hurls

itself

and

the stones soak it up.

In

them the music dies

under

the hands.

It's

hard dying at night, hard

to

die feeling your way.

The

way of the blind is

simpler,

the blind

cross the empty squares.

1967,

translated with

Wladimir

Weidlé

Cuốn sách về Brodsky này,

như lời Bạt cho thấy, có cùng tuổi [hải ngoại] của Gấu, 1997,

hay đúng hơn, kém Gấu ba tuổi.

Gấu làm quen Brodsky thời gian này, nhân

đọc Coetzee viết về những tiểu luận của ông, trên tờ NYRB;

bài tưởng niệm khi ông mất, của Tolstaya...

Trong cuốn này, có nhắc tới bài viết,

Gấu chôm, xen với những kỷ niệm về Joseph Huỳnh Văn, trong

bài “Ai cho phép mi là thi sĩ”

Post ở đây, rảnh rang lèm bèm sau.

Thú nhất câu: "Hãy nhớ Gấu, và

quên số mệnh cà chớn của Gấu"!

"Remember me, but ah! Forget my fate!"

Nghĩa địa Do Thái

ở Leningrad

Nghĩa địa" như bài thơ

được gọi, trong bài viết, thì chẳng hay ho gì,

không chỉ ở cái giọng kể lể, mà còn cả ở

cái chất thơ xuôi của nó. Khổ đầu thì còn

có vần điệu, nhưng sau biến thành thơ tự do. Ngoài

nó ra, không còn bài nào như thế,

trong số tác phẩm của Joseph... nhưng khi được 1 tay xb hỏi,

có cho nó vô 1 tuyển tập Những tiếng nói ở bên trong

[chiếc thuyền] Noé: Những nhà thơ Do Thái Hiện Đại,

do anh ta xb, hay là không [Anthony Rudolf, co-editor of

the international anthology Voices Within the Ark: The Modern

Jewish Poets (1980) tells me that when asked if he would be willing

to be included in the book], Brodsky nghiêm giọng phán, ta

"muốn" có nó, trong đó!

Hay, thí dụ, trong lần trả lời báo chí

Tháng Chạp, 1987, ở Stockholm, khi tới đó lấy cái

Nobel, “Tớ thấy tớ như 1 tên… Ngụy, dù

chưa từng biết truyền thống Ngụy nó ra làm sao”, và

nói thêm, “Về ngôn ngữ của riêng tớ, thì

đúng là của 1 tên… Mít”!

Là 1 tên Ngụy, thì giống như 1 tên

lưu vong, có tí lợi; nó đẩy tên đó

ra bên lề, thay vì ở trung tâm xã hội. Lũ

Ngụy có thói quen choàng cho chúng 1 màu

của chung lũ chúng, ở loanh quanh chúng. Lịch sử Ngụy

ban cho từng cá nhân Ngụy 1 thứ văn hóa, và

đây là nguồn sức mạnh của chúng, nhưng vưỡn không

làm sao giấu được nhược điểm, là ở bất cứ đâu, bất

cứ lúc nào, nó cảm thấy chẳng ra cái chó

gì cả, hắn đếch thuộc về ai, về đâu, đại khái thế!

The Word That Causes Death’s Defeat

Cái

từ đuổi Thần Chết chạy có cờ

Kinh Cầu đẻ ra từ một sự kiện, nỗi đau

cá nhân xé ruột xé gan, và cùng

lúc, nó lại rất là của chung của cả nước, một

cách cực kỳ ghê rợn: cái sự bắt bớ khốn kiếp của

nhà nước và cái chết đe dọa người thân thương

ruột thịt. Bởi thế mà nó có 1 kích thước vừa

rất đỗi riêng tư vừa rất ư mọi người, rất ư công chúng,

một bài thơ trữ tình và cùng lúc, sử

thi. Nó là tác phẩm của ngôi thứ nhất, thoát

ra từ kinh nghiệm, cảm nhận cá nhân. Tuy nhiên, trong

lúc chỉ là 1 cá nhân đau đớn rên rỉ

như thế, thì nó lại là độc nhất: như sử thi, bài

thơ nói lên kinh nghiệm toàn quốc gia….

Đáp ứng, của Akhmatova,

khi Nikolai Gumuilyov, chồng bà, 35 tuổi, thi sĩ, nhà

ngữ văn, trong danh sách 61 người, bị xử bắn không cần bản

án, vì tội âm mưu, phản cách mạng, cho thấy

quyết tâm của bà, vinh danh người chết và gìn

giữ hồi ức của họ giữa người sống, the determination to honor the dead,

and to preserve their memory among the living….

Trong 1 bài viết trên talawas, đại thi sĩ Kinh

Bắc biện hộ cho cái sự ông ngồi nắn nón viết tự

kiểm theo lệnh Tố Hữu, để được tha về nhà tiếp tục làm

thơ, và tìm lá diêu bông, rằng, cái

âm điệu thơ Kinh [quá] Bắc [Kít] của ông,

buồn rầu, bi thương, đủ chửi bố Cách Mạng của VC rồi.

Theo sự hiểu biết cá

nhân của Gấu, thì chỉ hai nhà thơ, sống thật đời của

mình, không 1 vết nhơ, không khi nào phải “edit”

cái phẩm hạnh của mình, là Brodsky và ông

anh nhà thơ của GCC.

Chẳng thế mà Milosz rất thèm 1 cuộc đời như

của Brodsky, hay nói như 1 người dân bình thường

Nga, tớ rất thèm có 1 cuộc đời riêng tư như của

Brodsky, như trong bài viết của Tolstaya cho thấy.

Bảnh như Osip Mandelstam mà

cũng phải sống cuộc đời kép, trong thế giới khốn nạn đó.

Để sống sót, Mandelstam cũng

đã từng phải làm thơ thổi Xì, như bà vợ

ông kể lại, và khi những người quen xúi bà,

đừng bao giờ nhắc tới nó, bà đã không làm

như vậy:

Nadezhda Mandelstam recalled

how her husband Osip Mandelstam had done what was necessary to survive:

To be sure, M. also, at the

very last moment, did what was required of him and wrote a hymn of praise

to Stalin, but the "Ode" did not achieve its purpose of saving his life.

It is possible, though, that without it I should not have survived either.

. . . By surviving I was able to save his poetry.... When we left Voronezh,

M. asked Natasha to destroy the "Ode." Many people now advise me not to speak

of it at all, as thou it had never existed. But I cannot agree to this, because

the truth would then be incomplete: leading a double life was an absolute

fact of our age and nobody was exempt. The only difference was that while

others wrote their odes in their apartments and country villas and were rewarded

for them, M wrote his with a rope around his neck. Akhmatova did the same,

as they drew-the noose tighter around the neck of her son. Who can blame

either her or M.

Roberta Reeder: Akhmatova, nhà thơ, nhà

tiên tri

Trong khi lũ nhà văn

nhà thơ Liên Xô làm thơ ca ngợi Xì và

được bổng lộc, thì M làm thơ ca ngợi Xì với cái

thòng lọng ở cổ, và bài thơ “Ode” đó cũng chẳng

cứu được mạng của ông. Người ta xúi tôi, đừng nhắc tới

nó, nhưng tôi nghĩ không được, vì như thế sự thực

không đầy đủ: sống cuộc đời kép là sự thực tuyệt đối

của thời chúng ta.

Tuyệt.

Chỉ có hai nhà

thơ sống sự thực tuyệt đối của thời chúng ta, bằng cuộc đời

“đơn” của họ, là Brodsky và TTT!

Etkind relates how this trial

pitted two traditional foes against each other, the bureaucracy and

the intelligentsia. Brodsky represented Russian poetry.

Viết Mỗi Ngày

Cách

Mạng Vô Sản của Lê Nin

The Russian revolution

Missed connection

Vladimir Lenin’s railway journey from Switzerland to Russia changed history

http://www.tanvien.net/TG2/tg2_ve_van_lichsu.html

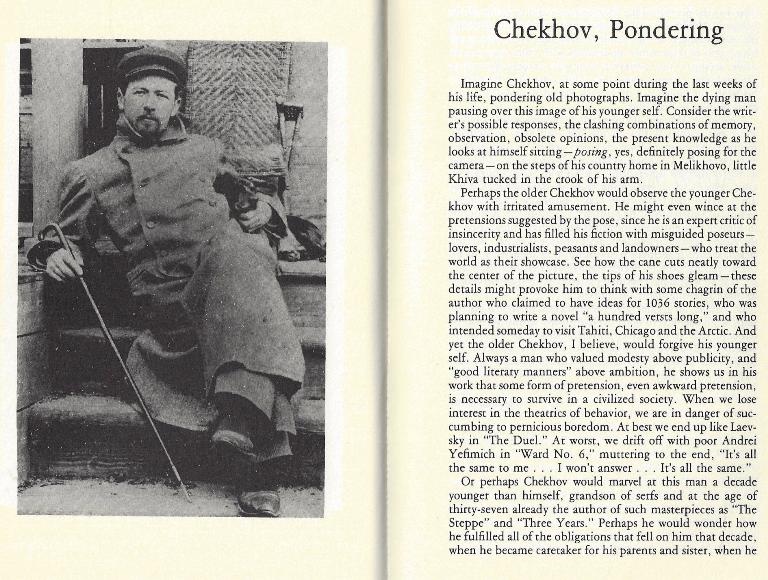

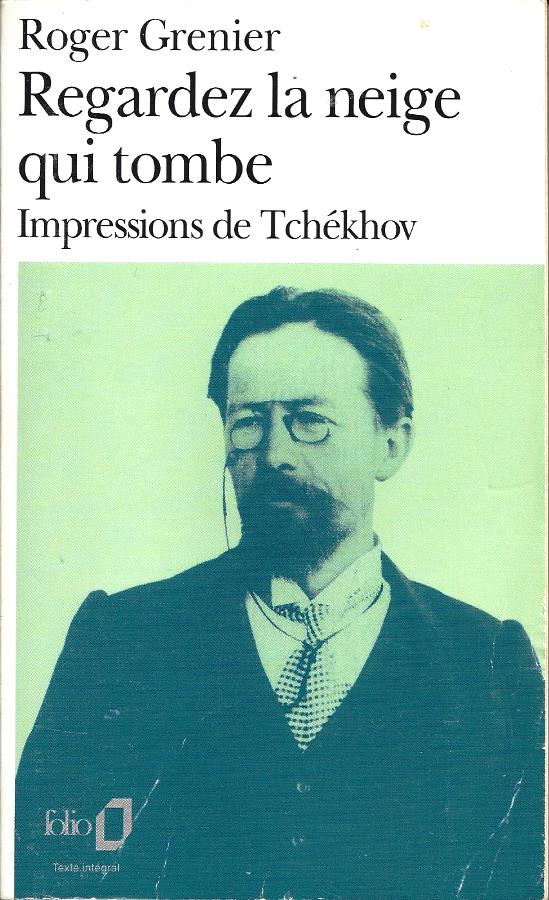

Chekhov, Pondering

Imagine Chekhov, at some point

during the last weeks of his life, pondering old photographs. Imagine

the dying man pausing over this image of his younger self. Consider

the writer's possible responses, the clashing combinations of memory,

observation, obsolete opinions, the present knowledge as he looks

at himself sitting -posing, yes, definitely posing for the camera-on

the steps of his country home in Melikhovo, little Khiva tucked in

the crook of his arm. Perhaps the older Chekhov would observe the younger

Chekhov with irritated amusement. He might even wince at the pretensions

suggested by the pose, since he is an expert critic of insincerity

and has filled his fiction with misguided poseurs- lovers, industrialists,

peasants and landowners-who treat the world as their showcase. See

how the cane cuts neatly toward the center of the picture, the tips

of his shoes gleam-these details might provoke him to think with some

chagrin of the author who claimed to have ideas for 1036 stories, who

was planning to write a novel "a hundred versts long," and who intended

someday to visit Tahiti, Chicago and the Arctic. And yet the older Chekhov,

I believe, would forgive his younger self. Always a man who valued modesty

above publicity, and "good literary manners" above ambition, he shows

us in his work that some form of pretension, even awkward pretension,

is necessary to survive in a civilized society. When we lose interest

in the theatrics of behavior, we are in danger of succumbing to pernicious

boredom. At best we end up like Laevsky in "The Duel." At worst, we

drift off with poor Andrei Yefimich in "Ward No.6," muttering to the end,

"It's all the same to me ... I won't answer ... It's all the same." Or

perhaps Chekhov would marvel at this man a decade younger than himself,

grandson of serfs and at the age of thirty-seven already the author

of such masterpieces as "The Steppe" and "Three Years." Perhaps he would

wonder how he fulfilled all of the obligations that fell on him that

decade, when he became caretaker for his parents and sister, when he

served as the doctor for the local peasants and as squire of the village

of Melikhovo and still managed to make the grueling trip across Siberia

to the island of Sakhalin. He might recall his pattern of responsible

moderation with more than a little pride, seeing in this portrait a man

who devoted himself to the problems of others and yet could come close

himself in his study for hours at a time, pick up his pen and hear the grass

singing in his mind. It could be, though, that the dying Chekhov would neither

wince nor marvel at this picture but turn away in despair, comprehending

more fully than ever before his own dishonesty. Here is Dr. Chekhov, villain

of self-deception. What did it matter that he suffered his first bout of

blood-spitting in 1884, shortly after graduating from medical school? What

did it matter that for thirteen years, though he treated many victims of

tuberculosis, he refused to identify the symptoms in himself? The disease

probably would have progressed at the same speed even had he sought treatment

earlier. But the lack of acknowledgement is troubling. If he'd been one

of his characters, his pose of health would have revealed itself as a lie,

and he would have seemed pathetic in his stubborn effort to make a lasting

name for himself. Of course, this Chekhov, the Chekhov lounging on the

steps of his Melikhovo home, collar turned up just so, will be remembered:

as the jaunty, brilliant writer, as the modest poseur and as a dying man

unable to acknowledge his illness because the telling would have made death

sensible. He preferred to tell of life.

-Joanna Scott

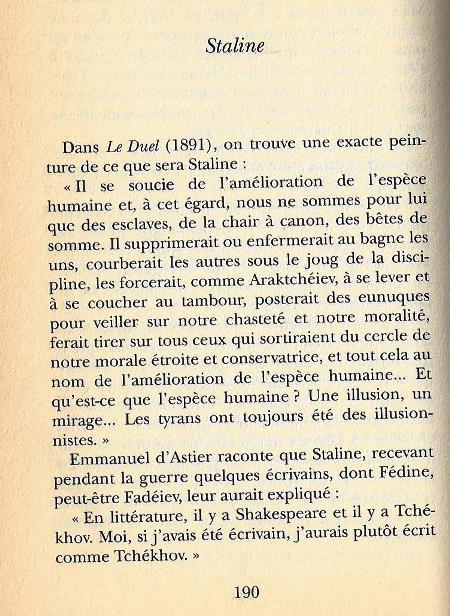

Trong Duel,

người ta nhận ra, đúng là chân dung Xì

sau này. Người quan tâm đến chuyện trồng người,

cải thiện nó, và dưới mắt người, cái giống người

như là hiện nay, thì là những tên nô

lệ, những con vật......

Trong 1 lần gặp gỡ những nhà văn, Xì

phán, trong văn chương, có Shakespeare, và

Chekhov. Tớ, nếu là nhà văn, chỉ mong viết được như Chekhov!

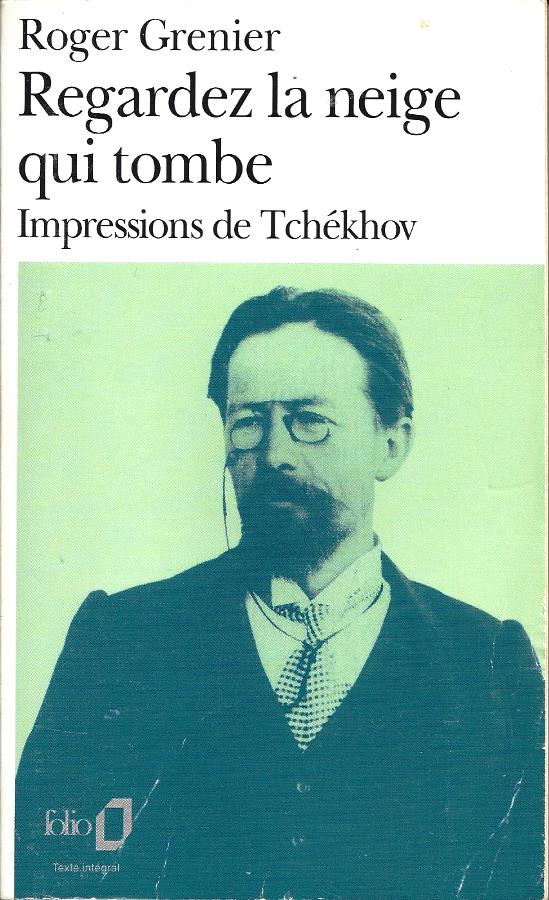

La petitesse de l'homme chez Anton Tchekhov

De Tchekhov et sur Tchekhov,

cette année (1), date du cinquantenaire de sa mort (1er juillet

1904), nous avons eu la possibilité de lire différentes

choses, et chaque fois, au cours de ces lectures, nous n'arrêtions

pas de nous demander: mais en quoi consiste vraiment le secret de

cet homme? Quel est le secret qui le rend d'autant plus cher et grand

et toujours actuel qu'il joue en «mineur », en décrivant

une réalité limitée, quel est le secret qui

le fait apprécier des lettrés les plus raffinés

comme du grand public des quotidiens du soir (qui, aujourd'hui encore,

lorsqu'ils veulent publier une nouvelle dont le succès sera certain,

puisent à sa source)? Il existe pour lui, en Union soviétique,

une affection qui touche à la vénération: et, de

ce petit médecin au regard étincelant et ironique derrière

son pince-nez, ils font presque un prophète de la sociéte

socialiste; alors qu'en Occident il est célèbre tantôt

comme un père du pessimisme et de l'agnosticisme libéraux,

tantôt même comme un symboliste mystique. Et tout cela,

il faut bien le souligner, sans que de son côté il ait

jamais fait preuve de lègereté ou de flatterie; en restant

toujours, au contraire, obstinément fidèle à

lui-même, sans pitié dans ce qu'il avait à dire,

en avancant sur un chemin sans détour, droit et linéaire.

Cet amour, parfois très fort, que l'on peut éprouver pour

lui, comme pour un frère péniblement retrouvé, avec

lequel on va pouvoir enfin tout expliquer de soi-même et tout comprendre

de lui, comment se justifie-t-il, s'il est par ailleurs le frère

de tant de gens, qui peuvent m'être sympathiques ou antipathiques,

amis ou ennemis?

Mon amour pour Tchekhov, je l'avoue,

a souvent été tourmenté par la jalousie.

Nous qui ne lisons pas le russe

et qui essayons de scruter la parole d'écrivains qui nous

sont chers à travers les traductions de même que l'on

devine les couleurs d'un visage à partir des ombres grises et

noires d 'une photographie, nous avons eu enfin cette année,

après tant de bonnes versions mais sans ordre et partielles, une

édition complète et ordonnée chronologiquement

de ses contes. «Édition complète », cela ne

veut pas dire qu'elle comprend tous les récits de Tchekhov: en effet,

il en a écrit plus de six cents, pendant les vingt et quelques années

qui vont de ses débuts dans la nouvelle dans La Cigale, un journal

humoristique banal, jusqu'aux longs récits des dernières

années, où il luttait contre la maladie qui l'emporta à

l'âge de quarante-quatre ans. Dans cette édition, il y a

les deux cent quarante morceaux qu'il a choisis en 1899 pour l'édition

définitive de ses oeuvres, en même temps que quatre-vingts

morceaux environ qu'il avait écartés, Ainsi pouvons-nous

suivre, année par année, les étapes d'un curriculum

littéraire si court et, repétons-le, si linéaire qu'on

a l' habitude de le considérer, dans l'ensemble, comme une totalité

homogène. Pour nous aider à retracer le chemin de son développement,

sont sorties cette année quelques biographies nouvelles dans des

langues occidentales : et je veux rappeler non pas tant un gros volume

paru en Angleterre (David Magarshack, Chekhov, Faber and Faber) que, plutôt,

un petit volume francais (Elsa Triolet, L' Histoire d' Anton

Tchekhov, Les Éditeurs francais réunis) qui offre

un raccourci efficace et essentiel de la vie et de l'oeuvre, de son époque,

des discussions et des problèmes d'alors, et qui focalise surtout

l'attention sur les aspects de sa figure qu'il nous intéresse

le plus d'éclaircir aujourd'hui.

Déjà, dans ses petites

nouvelles humoristiques, Tchekhov part avec une agressivite polémique

cruelle, baignant uniquement dans les faits (Le Gros et le Maigre,

Cameleon, Le Huitres, Le Sous-Officier Latrique) comme un Gogol qui

n' pas eu besoin d'une caricature déformante pour trouver ses

effets, mais les découvre sous ses yeux tels quels, prêts

à être esquissés d 'une annotation rapide, à

être racontés simplement, à voix basse. Mais si

Gogol trouvait de l’intérêt à dévoiler le

visage absurde, démoniaque, comiquement poignant qui se cachait

sous la réalité bureaucratique la plus quotidienne de la

Russie, Tchekhov, qui commence à écrire trente ans après

la mort de Gogol, veut fouiller différemment la réalité,

Dans la nouvelle La Fille d' Albion, qui date de

1885, nous trouvons déjà Tchekhov à son plus haut

degré, et le métal dont il forge ses contrastes comiques

ou dramatiques : la dignité de l'homme. Dans des nouvelles comme

celle-ci, ou comme La Choriste (1886), plus il fouaille ses petits humains,

plus il en découvre les égoismes, les faussetés

et les mesquineries sous le masque de leur fausse «dignité»,

plus se révèle à nous quelque chose qui résiste

à la dégradation, quelque chose de supérieur à

la bassesse générale, une qualité impalpable

que nous devons recommencer à appeler dignité humaine,

une dignité tout à fait opposée à celle,

hypocrite et formelle, des moeurs bourgeoises. Mais Tchekhov atteint

ses meilleurs résultats lorsque la decouverte de la fausse

dignité et les retrouvailles avec la vraie ont lieu chez le même

personnage ; lorsque le couteau qui ouvre l' abcès touche la

chair vive. Et l' on voit apparaitre alors la «pitié»

de Tchekhov, toujours d'autant plus présente qu'il est «sans

pitié » : voilà que, après avoir découvert

sous le personnage le petit-bourgeois - sa mesquinerie et son horreur

historique -, sous le petit-bourgeois, il découvre l 'homme.

Avec La Steppe (1888), événement

capital dans l'histoire de la narration moderne, Tchekhov commence

à avoir une conscience plus précise de l'importance

littéraire de son travail, et aussi de sa responsabilité

de citoyen. La critique braque son regard sur lui, et on lui reproche,

à droite comme à gauche, le fait de «ne pas prendre

parti ». Mais Tchekhov, dans ce qu'il écrivait, avait

toujours pris un parti, même s'il ne correspondait à aucun

des partis qui évoluaient dans le monde intellectuel de la bourgeoisie

russe d' alors. Au contraire, il en révelait les limites et

les échecs : dans les longs récits qui vont du Jour de

Fête (1888) jusqu'à La Fiancée (1904), ce n' est qu

'une galerie dintellectuels velléitaires et décus, de

vies de province consumées dans la paresse, de mariages et d'amours

gâchés, de femmes toujours plus vitales, ou plus justes,

ou moins coupables que les hommes. Et au centre de ces histoires il y a

presque toujours un «que faire?» politique et social, non

pas avec la ferveur qui avait été celle de Tchernichevski

et que l' on retrouvera chez Lénine, mais avec l'incertitude de

la période de réaction et de reflux révolutionnaire

du règne d' Alexandre III et des premières années

de Nicolas II, avec un manque de perspectives historiques que l'écrivain

voit se refléchir dans les vies privées, dans les habitudes,

dans les sentiments.

Plus on avance dans la lecture de Tchekhov,

plus on rencontre de personnages qui, à la fin, décident

de «travailler sérieusement » ou qui parlent

de la vie merveilleuse qu'il y aura« sur la terre dans cent,

deux cents ans », ou de la« belle bourrasque qui balaiera

tout» : deux phrases qui ont aujourd'hui un sens prophétique

suggestif, mais qui sont toujours indéterminées,

qui n'évoquent pas d'images concrètes et précises

comme nous avons l'habitude d'en trouver chez lui. Ce n'est que leur

accent de sincérite, presque de document d'un état d'âme

de l'époque, qui fait qu'elles ne nous paraissent jamais rhétoriques

; mais la mort de Tchekhov, à la veille de la première révolution

russe de 1905, acquiert presque une signification symbolique: il est

l'écrivain d'une humanité qui cherche sa voie.

En ce sens, Salle 6 (1892)

se détache de tous les autres longs récits non seulement

parce que c'est l'acte d'accusation le plus terrible et géneral

que Tchekhov ait jamais écrit (le jeune Lénine en fut

fasciné et bouleversé), mais parce qu'il investit un

moment de crise de la pensée scientifique et humanitaire bourgeoise,

la tentation de penser que tout est inutile, que le mal est invincible,

que la matière doit être considérée vanité,

et la douleur illusion. Si quelques tentations spiritualistes peuvent

avoir touché l'auteur du Pari ou du Moine noir, elles trouvent

ici un démenti, résultat d'une décision en même

temps douloureuse et féroce.

Tchekhov, le médecin éducateur

à l'ombre de la culture positiviste, et qui avait saisi

ce qu'il y avait en elle d'élan humanitaire et progressiste,

en cerne aussi, avec une sensibilité précise, les crises

et les deviations. Dans Le Duel, il nous a donné,

en 1891, un portrait parfait de nazi, un naturaliste qui soutient

la suppression des plus faibles de la part des plus forts, un portrait

où il n'y a rien à changer, ni le type physique, ni les

discours, ni le nom allemand, ni l'idéologie pseudo-scientifique,

pour retrouver en face de nous un de ceux qui, cinquante ans plus tard,

vont torturer l'Europe. Et dans ce personnage (comme dans celui de Dans

le domaine, qui est a peu près son pendant) Tchekhov n'a pas

manqué de laisser entrevoir que lui aussi n'est qu'un pauvre

homme qui pourrait être capable de bonnes actions, mais qui

n'en est pas pour autant moins féroce et inhumain. II ne s'agit

pas de superficialité sentimentale chez Tchekhov, ni d'un «Aimons-nous

les uns les autres » de la sceptique indulgence amorale qui a

tant de racines dans les moeurs italiennes; c'est la douleur sévère

pour tout ce que l'homme gaspille de lui-même, pour ce qu'il

pourrait être et qu'il n'est pas. Tchekhov a compris cela surtout

de cette société qui est encore la société

dans laquelle nous vivons: que de choses irrécupérables

sont quotidiennement perdues, que de beauté, que d'amour, que

de qualités qui pouvaient être tournées vers le

bien, que de vies gaspillées, consumées vainement. Et

en cela il n'est ni élégiaque, ni résigné

: il s'en prend à nous, il est d'une sévérité

féroce, C'est la sa morale, la “porte étroite” qu'il

ouvre à ses personnages et à nous. C'est pour cela qu'il

demeure, d'autant plus qu'il est clair et sans facons, un écrivain

« difficile », «peu commode» : parce qu'il est

plus facile de l'éviter et de broder autour de lui que de l'accepter

tel qu'il est.

Italo: Pourquoi lire les classiques

La petitesse de l' homme chez Anton

Tchekhov

Cõi người bé tí

ở Chekhov

Mon amour pour Tchekhov,

je l'avoue, a souvent été tourmenté par la

jalousie: Cái tình yêu của tôi với Chekhov,

có cái sự ghen tuông, đố kỵ ở trỏng.

Dans Le

Duel, il nous a donné, en 1891, un portrait parfait de

nazi, un naturaliste qui soutient la suppression des plus faibles

de la part des plus forts, un portrait où il n'y a rien à

changer, ni le type physique, ni les discours, ni le nom allemand,

ni l'idéologie pseudo-scientifique, pour retrouver en face

de nous un de ceux qui, cinquante ans plus tard, vont torturer l'Europe.

Trong Le Duel, ông ta đã cho chúng

ta chân dung tuyệt hảo của Nazi...

Il existe pour lui, en Union soviétique,

une affection qui touche à la vénération: et,

de ce petit médecin au regard étincelant et ironique

derrière son pince-nez, ils font presque un prophète

de la sociéte socialiste; alors qu'en Occident il est célèbre

tantôt comme un père du pessimisme et de l'agnosticisme

libéraux, tantôt même comme un symboliste mystique.

Ở Liên Xô, ông được coi như nhà

tiên tri của XHCN, ở Tây Phương, ông nổi tiếng,

khi thì như là người cha của chủ nghĩa bi quan, khi

thì như 1 biểu tượng thần bí..

Ai Điếu Roberto Bolaño,

người sáng tạo ra chủ nghĩa 'infrarealism'

Roberto Bolaño, who has died

at Blanes in northern Spain of liver failure, aged 50, was one

of the most talented and surprising of a new generation of Latin American

writers.

Born in the Chilean capital of Santiago, Bolaño

was typical of a generation of Latin American writers who had

to cope with exile and a difficult relationship with their home country,

its values and its ways of seeking accommodation with a turbulent history.

Bolaño turned to literature to express these experiences, mixing

autobiography, a profound knowledge of literature, and a wicked

sense of humour in several novels and books of short stories that

won him admirers throughout Latin America and Spain.

Bolaño spent much of his adolescence with

his parents in Mexico. He returned to Chile in 1972, to take part

in President Allende's attempts to bringing revolutionary change

to the country. Arrested for a week after the September 1973 Pinochet

coup, Bolaño eventually made his way once more to Mexico,

where he embarked on his literary career. At first he wrote poetry,

strongly marked by Chilean surrealism and experimentalism, but after

moving to Spain in 1977 he turned to prose, first in short-story

form and then more ambitious novels.

His mischievous spirit upset many fellow writers,

who often bore the brunt of his attacks. Fed up with the pious

sentimentalism of the kind of socially committed literature he

felt was expected of Chilean writers, he aimed to subvert good taste,

revolutionary or conservative. This iconoclasm led to books such

as the History Of Nazi Literature In Latin America, an invented genealogy

of writers.

In 1998, Bolaño published his best-known

work, the sprawling novel Los Detectives Salvajes (The Wild

Detectives), a challenging mixture of thriller, philosophical and

literary reflections, pastiche and autobiography, which he baptised

"infrarealism". The novel won him the Herralde and Romulo Gallegos

prizes, and established Bolaño as one of the foremost writers

in the Hispanic world.

English readers so far have only been able to

read By Night In Chile, published by Harvill this year. This is

the most straightforward of his books, looking back as it does to

the Pinochet days in Chile and the coexistence of evil, compromise

and literature in extreme situations.

When Bolaño came to London early this year

for the English publication of By Night in Chile, he was already

very ill from a longstanding liver complaint. Despite this, he

was still talking non-stop of the many projects he was involved

in, including a mammoth novel provisionally entitled 2666, already

more than 1,000 pages long, that dealt with the murders of more than

300 young women in the Mexican border town of Ciudad Juarez, another

novel, and a new collection of poetry.

But what most delighted him during his London

visit was the fact that he was already becoming better known

in Spain as a fictional character than as his "real" self. This

is because he is one of the main characters in the Spanish bestseller

by Javier Cercas, The Soldiers Of Salamis, where "Roberto Bolaño"

helps the author to successfully complete his novel.

This mingling of reality and fiction seemed to

Bolaño a confirmation that life and literature are of

equal importance. As he said at the time, "You never finish reading,

even if you finish all your books, just as you never finish living,

even though death is certain."

Bolaño had faced this certainty for years,

as his liver deteriorated. He died in hospital while awaiting

a liver transplant, and is survived by his wife Carolina and two

children, Alexandra and Lautaro.

· Roberto Bolaño, writer, born April

28 1953; died July 15 2003.

MADELEINE THIEN

Dream of the Red Chamber

My mother's favorite book was

the Chinese classic novel Dream of the Red Chamber, also known

as The Story of the Stone, also known as A Dream of Red Mansions.

This was the only work of fiction on her bookshelf. I remember picking

the novel up only once when I was young. I was drawn to its magisterial

heft, to the consolidated weight of more than a thousand pages. But

because I could not read Chinese, I gravitated instead to her Chinese-English

dictionary, a heavy yet small book, the size of my hand that translated

shapes into words (book). My mother passed away suddenly in 2002,

and her copy of Dream of the Red Chamber vanished.

The novel was written 250 years

ago by Cao Xueqin, who was still writing it when he died suddenly

in 1763. Approximately twelve copies of Dream of the Red Chamber

existed in the years following his death, handwritten editions made

by his family and friends. The manuscripts differed in small ways from

one another, but each was eighty chapters long. Unfinished, the novel

ended almost in mid-sentence.

Those handwritten copies began

to circulate in Beijing. Rumors spread of an epic, soul-splitting

tale, a novel populated by more than three hundred characters from

all walks of life, a story about the end of an era, about the overlapping

lines of illusion and existence, a novel that took hold and would

not let you go. In 1792, nearly thirty years after Cao Xueqin's death,

two Chinese scholars came forward and claimed to be in possession of

the author's papers. They proceeded to publish what they said was the

complete manuscript, consisting of one hundred and twenty chapters,

thirteen hundred pages. Movable type had existed in China since the eleventh

century, but this was the first time Dream of the Red Chamber appeared

in print.

It has been the pre-eminent

Chinese novel ever since, attracting legions of scholars-so many

that they form a movement, Redology. Some believe that, for reasons

unknown, Cao Xueqin destroyed the last forty chapters of his novel,

that the two scholars finished the book themselves. Today in China

there are more than seventy-five editions. Some are eighty chapters,

others are one hundred and twenty, and some are one hundred and ten.

Dream if the Red Chamber has multiple endings and it also has no ending.

A few years ago, I began writing

a novel set in Shanghai. My own novel circles around a hand-copied

manuscript with no author, a story with no beginning and no end.

I knew nothing about the story surrounding Dream of the Red Chamber

because I had never read the novel; no one had mentioned it in any literature

course I had ever taken. A couple of years ago, missing my mother,

I finally began to read it. The novel took root in me. When I learned

of the handwritten copies, the continuation, the unknown authorship,

I felt oddly, exhilaratingly, as if I had always known this story.

I had folded it into my own book: a truth unwittingly carried in a fiction,

an illusion as the structure of a truth.

Dream of the Red Chamber is

hands down the most widely read book in the Chinese-speaking world,

making it perhaps the most read novel in history. Professor John Minford,

who translated an edition with celebrated translator and Chinese scholar

David Hawkes, described it as a novel that combines the highest qualities

of Jane Austen, William Thackeray, Marcel Proust, and Honore de Balzac.

After 250 years, readers continue to decode its mysteries. Readers

like my mother felt ownership over the novel. With Dream of the Red

Chamber, none of us can ever know where the ending lies or what only

another beginning is. The novel itself is a playful and profound mirror

to the life of the imagination. Lines from the first chapter read, "Truth

becomes fiction when the fiction's true. Real becomes not-real where

the unreal's real. "

I still have my mother's dictionary.

I often wonder what happened to her copy if Dream of the Red

Chamber. I wonder whether it had eighty chapters, one hundred

and twenty, or one hundred and ten. It was her girlhood copy. She'd

had it through all her migrations, carrying it across the seas from

Hong Kong to Canada. I had wanted to keep it all my life, but while

I grieved my mother's sudden death, someone reached out for the book

on the shelf. They lost themselves in its love triangles, its forgotten

era, its intricate dance between this world and its dream. They carried

the book away with them, into its next life.

The Adventures of Tintin

PICO IYER

By the time I was five, I was used

to my impenitently spirited father bringing strange things into our lives.

I could perch on the stool he'd acquired made out of an elephant's foot,

spying on the robed Tibetan monks who came to him for tutoring in Plato and

Spinoza. I could stare at the photo he'd brought back of the Dalai Lama,

four years old, already seated on the Lion Throne in Lhasa (a present the

Tibetan leader had sent me, through my dad, following their first meeting,

in 1960). After three months away in West Africa teaching political theory,

suddenly my old man was dancing to highlife music in our little flat on Oxford's

Winchester Road, cheerfully oblivious of the duffle-coated, tow-headed professors'

children just outside, heading down the street to the Dragon School or its

prequel, the Squirrel.

As a child, of course, I took

this to be quite normal; the old Englishwoman we went to see in

the evenings used to magick elaborate horoscopes, all circles and

esoteric scribbles, from the thick ephemerides on her shelves. The

tall, no-nonsense the memsahib who looked after her-her daughter

and the very picture of a commander of the British Empire-had (I learned

much later) spent time as a Buddhist nun in Thailand. That handsome

colleague of my father 1 saw at Christmas parties at St. Antony's turned

out to be the legendary photographer of Tibet in the 1930s, Fosco

Maraini, who had cut off his own finger during the war to shame his

Japanese captors.

One day-my parents had, quite

fittingly, moved to California by now, though 1 continued going

to school in Oxford-I headed down a narrow, barely

lit staircase in the home of the former Buddhist nun, now my unofficial

godmother. Waiting for me at the bottom was a sparky boy journalist

in an over-coat, who'd been pierced by a vision of a stricken Chinese

friend in the snow and left Europe for the Himalayas. Within seconds,

I was following this cub reporter to the Caucasus and then through

the forests of Yugoslavia, all sinister black limousines and grimacing

operatives. I thought nothing of accompanying him into the richly colored

bazaars of the Andes, through rickshaw-filled streets in a red-lanterned

Shanghai, even to the moon. I would never have guessed then that a

journalist, who seemed to file no stories, had no apparent bosses or

office, never thought about deadlines, and simply followed adventure

wherever it took him would one day be a description of me.

Oxford in those days was a

network of children's possibilities, if you knew where to look.

A few hundred yards from my bedroom was the pub where C. S. Lewis

and J. R. R. Tolkien exchanged stories of Narnia and Middle Earth.

Up the street a little was the garden in which the Mad Hatter and

the Cheshire Cat leapt into life. Toad of Toad Hall was just around

the bend, along a drowsy river, and my hero and designated alter ego-another

foreigner appearing in England in almost the same year as I did, Paddington

Bear-inhabited a world that seemed indistinguishable from the cozy

rituals that kept us happily in place in North Oxford.

But Tintin was the one to fling

open a lifestyle for me, if only because he seemed so unrooted

and so restless. We never saw his home; we could never associate

him with a family. All he had was a movable feast of lovably unpredictable

friends, a loyal four-legged companion, and a blend of curiosity

and conscience that seemed to land him always in rapturously unexpected

settings that his creator, Hergé, had fashioned out of constant

trips to museums and through books.

The stories were unexceptional.

The characters were one-dimensional. I can't say my imagination

was deepened or stretched by the books, as it would be by, say,

Ursula Le Guin's ageless and profound Earthsea novels. Yet the beauty

of Tintin was that the background was the point,

at least for me. It was never the protagonist, the dialogue, the plot

that mattered; what it gave this small reader was a hunger to be out

in the world, in the midst of bustling markets and unreadable strangers,

of words lost in translation and levitating monks, where everything

we once thought strange would come in time to be familiar.

Paddington Bear gave me a template

out of which to form a character; but it was Tintin who threw

open the doors to an entire destiny. +

On childhood Books

Brick, A Literary Journal, n# 95, Summer 2015

Six

Poets Hardy to Larkin

The Moon

TTT 10

năm

SN_GCC_2016

Viết Mỗi Ngày

This prolific

novelist is little known to English-language readers. A new series of

translations will introduce them to his sinister work

Trùm tiểu thuyết đen của Tẩy.

Như Simenon, cả hai đếch thèm chơi với giới văn nhân,

và chẳng hề được coi là trí thức Tẩy

Dard, like

Simenon, relished his status as a best-selling provincial outsider. “Neither

of them had much connection with the literary world,” Bellos explains,

“and neither could be considered a ‘French intellectual’: both left school

at 15.” However, as much as his great counterpart, Dard roots slaughter

and mayhem in the implacable collision of desire and destiny. That deadly

machine can feel as classically French as a play by Racine or a novel

by Balzac.

Both protagonist and victim, Albert cannot escape his fate, and

nor does he wish to. Dard, notes Bellos, “had a view of humanity almost

as unflattering as Simenon’s”. In a spasm of compassion, Albert gives

a Christmas-tree decoration to Lucienne: a velvet bird in a silver cardboard

cage. That present will help to damn him. The cage-door swings shut, and

he locks himself inside.

Bird

in a Cage by Frédéric Dard, translated by David

Bellos (Pushkin Vertigo)

Ui chao,

lại nhớ thời mới nhớn, mê Simenon như điên. Lúc nào

cũng thủ 1 cuốn Simenon trong túi. Mỗi lần được phái đi

sửa máy tại 1 đài Bưu Điện địa phương, là phải có

Simenon cùng đi. Gấu khá tiếng Tẩy là nhờ tiểu thuyết

đen Tẩy

Opened in

1997, the world’s only phallological museum has been growing ever since.

This year the exhibition will attract 50,000 visitors

Mit Critic

Một ý

nghĩ:

Đối với

nhà văn đích thực, ngày mai phải viết hay hơn hôm

qua, đó không chỉ là một đòi hỏi mang tính

thẩm mỹ mà còn là, thậm chí trước hết là,

một đòi hỏi mang tính đạo lý - cũng bức thiết và

tự nhiên giống như ngày mai phải sống đẹp hơn hôm

qua.

Tuy nhiên, mặt khác,

nếu bạn không làm được như vậy, thì ít nhất

bạn hãy bao dung với mình nếu biết bạn đã cố hết sức.

... See More

Đấng này,

Gấu đọc, ngay từ khi vừa xuất hiện trên diễn đàn VHNT trên

lưới, của PCL, và thú thực, không có ý

kiến.

Khác hẳn trường hợp Nguyễn Quang Lập, cũng xuất hiện, cũng

trên VHNT, đọc 1 phát là trúng đòn

liền, và là cái mẩu Cục Uất của anh ta.

Bọ Lập sau đó, nổi như cồn, với loạt bài, trên

TV có post lại. Nhưng sau đó, là hết. Gấu đã

từng dùng hình ảnh ánh lửa ma trơi, để diễn tả trường

hợp của anh ta.

Nhưng vấn đề của TTCD, khác hẳn.

Thì nói toạc ra ở đây, anh ta viết hoài

thì cũng vẫn mãi như thế.

Và quả nó liên quan đến mỹ, đến đạo lý,

nhưng không phải

như anh ta hiểu.

Trường hợp của TTCD, là trường hợp của… GCC, thời

mới lớn, và Sartre diễn tả thật là thần sầu. Nhớ, Gấu, thú

thực, đọc 1 phát, lại 1 phát, là thấm cả 1 đời.

Sartre phán: Vảo mỗi thời đại, con người nhận ra mình,

lọc ra mình, khi đối diện với tha nhân, tình yêu

và cái chết

A chaque époque, l'homme se choisit en face d'autrui, de

l'amour et de la mort.

Theo GCC, TTCD, như cả 1 thời của anh ta, khôn quá,

hoặc nhát quá, chẳng chọn gì!

Anh ta không dám lọc mình ra, giữa cả 1 thời của anh ta! (1)

(1)

http://www.tanvien.net/tap_ghi_7/chuoi_5.html

Tại sao

mày cứ viết về mấy chuyện "chính trị", nhắc đến tụi chúng

nó làm gì vậy? Chúng nó đâu

có đáng để cho mày viết?

Một ông nhà văn Miền Nam, cũng bạn văn của Hai Lúa

ngày nào, tỏ ra bực mình.

Nhưng Hai Lúa đâu có viết về chúng

nó, mà viết về những người mà chúng nó

ngồi lên đầu!

http://www.tanvien.net/gioithieu_02/cuc_uat.html

Ui chao, Sartre, Camus và

thời mới lớn của Gấu, và những câu thần chú.

Con người bị kết án phải tự do. L’homme est condamné

à être libre.

Địa ngục là tha nhân. L’enfer, c’est les autres.

Kỹ thuật tiểu thuyết luôn qui chiếu về siêu hình

học của tiểu thuyết gia, une technique romanesque renvoie toujours à

la métaphisique du romancier. Sartre đọc Âm Thanh và

Cuồng Nộ của Faulkner. Câu phán này quả là quá

khủng khiếp, vì nó trở thành kim chỉ nam đối với cái

việc điểm 1 cuốn sách. Sartre đọc Faulkner, và khám

phá 1 siêu hình học về thời gian: Trong Âm Thanh

và Cuồng Nộ, Faulkner đập nát thời gian của tiếng tích

tắc của đồng hồ, và xây dựng 1 thời gian khác, với tiếng

hú của 1 tên khùng, đây là câu chuyện

được kể bởi 1 tên khùng, đầu âm thanh và cuồng

nộ, và chẳng có ý nghĩa gì hết

1. Thế kỷ 20 của ai?

Triết gia người Pháp, Bernard-Henry

Lévy trả lời bằng cả một cuốn sách: Thế kỷ của Sartre (nhà

xb Grasset, Paris).

G. Steiner, trong bài viết "Triết gia cuối cùng?" trên

tờ TLS (The Times Literary Supplement 19 May, 2000), đã nhắc tới

một phương ngôn của người Pháp, theo đó, trong những

thập kỷ cuối thế kỷ 20, ngôi sao của Sartre lu mờ so với những "địch

thủ" của ông như Camus, Raymond Aron, bởi vì thời gian này,

ông còn ở trong lò luyện ngục (purgatoire). Và

đây là "phần số", chỉ dành cho những triết gia lớn,

tư tưởng lớn. Theo ông, hiện nay, ở Pháp, Đức, Ý, Nhật,

và một số quốc gia Đông Âu, thế giá và

huyền thoại của nhà văn đã từng từ chối giải thưởng Nobel

văn chương này, đang ở trên đỉnh. Ở đâu, chứ ở Pháp

thì quá đúng rồi: sau 20 năm ở trong lò luyện

ngục, Sartre trở lại, và đang tràn ngập trong những tiệm sách,

với nào là tiểu sử (loại multi-volume), nào hội thảo,

đối thoại, gặp gỡ (rencontres)… Theo như Jennifer Trần tôi được biết,

tạp chí Văn, trong tương lai, sẽ dành trọn một số báo

để nhìn lại "triết gia cuối cùng của nhân loại", đặc

biệt bởi những nhà văn Miền Nam đã một thời coi ông

là "thần tượng", như Huỳnh Phan Anh, Đặng Phùng Quân…

"Địa ngục là

những kẻ khác", "Người ta không thể bỏ tù Voltaire",

"Con người bị kết án phải tự do", "Con người là một đam mê

vô ích", "Tự do phê bình là hoàn

toàn ở Liên Bang Xô-viết (La liberté de critique

est totale en URSS), "chủ nghĩa Cộng sản là chân trời đừng

mong chi vượt được của thời đại chúng ta (Le marxisme est l’horizon

indépassable de notre temps)… nhưng hình ảnh một ông

già mù phải nhờ bạn dẫn tới bàn hội nghị, để tranh

đấu cho một con thuyền cho người vượt biển, vì muốn cứu những xác

người trên biển Đông mà đành phải bắt tay với

kẻ thù và cũng đã từng là bạn… hình

ảnh đó đã vượt lên tất cả… nhưng thôi, xin hẹn

gặp Văn, số đặc biệt!

Cái tay

TTCD này, khi anh ta và đồng bọn làm trang e-Văn, Gấu

mặt dầy gửi bài liền, chẳng đợi mời. Chỉ đến khi GCC gửi 1 bài

dịch trên TLS, kèm luôn bản tiếng Anh, và khi

bài post lên, thấy đề TTCD hiệu đính, Gấu bèn

mail hỏi, anh ta chỉ ra mấy chỗ Gấu dịch sai, mà sai thật, Gấu mới

hỡi ơi, vì cái đạo hạnh của anh ta.

Cái từ hiệu đính, như Gấu đã từng nói,

rất cao quí, không thể đem ra dùng 1 cách khinh

xuất như thế, mà dùng như thế là làm nhục tòa

soạn e- Văn, chứ không phải người cộng sự.

Sến cũng y chang, vô tư đè bài viết của GCC ra

đề tên 1 tên khốn kiếp vô, hiệu đính!

Đây là sự khác biệt giữa văn minh và dã

man mà DTH đã từng chỉ ra.

Với đám Ngụy, đây là công việc bếp núc

của 1 toà soạn, khi họ “edit”, biên tập, một bài viết của cộng sự, và

nó không chỉ hạn hẹp trong việc sửa những lỗi dịch sai.

Khi biên tập xong, họ gửi cho tác giả, và xin ý

kiến, nếu OK, họ đăng, không, họ gửi trả lại bài viết.

Từ “hiệu đính” được dùng trong những nghi lễ trang trọng

hơn nhiều.

Một tay mới viết, biết sức mình, bèn nhờ 1 đàn

anh mà anh thực tình coi trọng, coi lại bài viết, “xin

anh hiệu đính cho em, và cho phép em để tên anh

lên đầu bài viết”

Đó là 1 vinh dự của lũ văn minh, vậy mà bị tên

này, cũng như Sến, làm thành 1 trò nhục mạ

người cộng sự.

Sến chẳng đã từng đăng bài viết của Nguyễn Văn Lục, và khi từ chối, ông

ta viết mail hỏi, Sến làm nhục ông ta bằng câu trả

lời, viết dưới tầm của trang của tôi!

Gấu đã

từng làm những công việc như vậy, mà chưa từng để

tên Gấu vô, như 1 kẻ hiệu đính. Nhờ vậy mà thoát

chết trong nhà tù VC, như đã từng lèm bèm

nhiều lần, khi sửa bài viết của Nguyễn Mai, khi phụ trách

phụ trang văn học của

tờ Tiền Tuyến

Những Hình Hài Nobel

http://www.tanvien.net/chuyen_ngu_2/nobel_bodies.html

Nguồn: Nobel Bodies, Phụ trang văn

học Thời báo London (TLS), số ngày 15/10/2004.

Nguyễn Quốc Trụ dịch

Chú thích: Đăng lại bản dịch trên e-Văn. Cám

ơn BBT, đặc biệt TTCĐ, đã sửa giùm một số sai sót.

NQT

http://phovanblog.blogspot.ca/2016/10/jane-eyre-ban-tay-che-dong-bao.html

Nhân loại ngày

nay thừa hưởng không ít những tác phẩm

văn học thường được gọi là kinh điển. Chúng là

những công trình trước tác của nhiều thiên

tài thuộc nhiều dân tộc, và từ khi tác

phẩm ra đời cho đến nay, trải qua nhiều thế hệ người đọc,

vẫn không phai nhạt giá trị nghệ thuật lẫn

nhân sinh. Dù trải qua nhiều thử thách

và những biến đổi ý thức hệ, lịch sử, chính

trị, xã hội, chúng vẫn không hề có

dấu hiệu chìm vào quên lãng. Nếu

cần chúng ta có thể liệt kê vài cuốn

tiêu biểu như Don Quixote của

văn hào Tây Ban Nha Miguel de Cervantes, hay cuốn

Chiến tranh và hoà bình

của văn hào Nga Lev Tolstoy, hay cuốn Những người khốn

khổ của văn hào Pháp Victor Hugo. Chúng

là gia sản văn hóa chung muôn đời của tất

cả chúng ta, không riêng một ai, và

đóng góp một phần không nhỏ vào đời

sống tinh thần của mọi sắc dân trên thế giới.

TYT

Note: GCC sợ đấng này

lộn từ kinh điển, academic, với từ cổ điển, classic.

Bởi thế, Calvino mới hỏi

và cùng lúc, trả lời bằng cả

1 cuốn sách: Tại sao chúng ta vưỡn đọc cổ điển?

Và cái câu khen bảnh nhất 1 cuốn sách

vừa mới ra lò, là đã thành

cổ điển!

Đã 1 bạn Cà

lầm “kinh điển” với “kinh nguyệt”, khiến cả 1 một diễn

đàn Bi Bi Xèo lầm theo.

Giờ đến đấng này!

GCC đã nói rồi, lưu vong, trễ quá,

càng trễ, mộng càng lớn, nghĩa là chỉ mong kết

bạn với đám viết lách, cái sự chửi bới, dọn dẹp như sau này,

là sau khi được bẩy bó, bèn dùng cái

bonus thời gian vào cái việc nhơ bẩn.

Hai vị hộ pháp của TV có lúc bực mình,

sao ưa cà khịa như thế, chửi người, dù thắng, thì

cái phần người của mi cũng bị sứt mẻ.

Nhưng theo GCC, rõ ràng là, trong giới

viết lách hải ngoại, gần như không có lấy 1 tên, có lấy 1 chút

đạo hạnh.

Đó là sự thực.

Và phải có 1 tên dám vào

địa ngục, làm cái việc, chỉ cho chúng thấy, chúng

nhơ bẩn quá, hà, hà!

Bởi là vì, không lẽ lui cui mất 20 năm,

làm trang Tin Văn, không được tí quà?

Quà làm trang TV là vạch ra cái

phần vô hạnh, vô đạo đức của lũ Mít cầm viết!

Chúng viết như kít, là do đạo hạnh

khốn nạn quá!

Cái gì làm cho tên ngồi bên

ly cà phê, làm thơ, nhớ bạn hiền, chôm thơ

Joseph Huỳnh Văn, trên trang Tin Văn nhưng lại nhớ mang máng

là đọc trên tờ Thời Tập của VL?

Cái gì làm 1 tên núp váy

đàn bà viết cực nhơ bẩn về những người viết đã

chết, như TTT, NXH, hay những vị còn sống, như MN, TTNgh, đều

là những người thành danh, có tác phẩm nổi

tiếng, chẳng hề thù

oán gì hắn, và, như Gấu, chẳng hề biết hắn là

thằng chó nào?

From:

To:

Cc:

Sent: Thursday, August 23, 2001 5:30 PM

Subject: Fw: Nguye^~n Quo^'c Tru.

Chao anh Tru

Them mot doc gia "sensitive" ve chuyen ve VN

Anh Tru co muon viet tra loi doc gia nay?

pcl

----- Original Message -----

From:

To:

Sent: Thursday, August 23, 2001 2:07 PM

Subject: Nguye^~n Quo^'c Tru.

Xin cha`o ca'c ba.n,

Ma^'y tua^`n na`y ddo.c ba'o chi' ha?i ngoa.i cu~ng nhu+ trong nu+o+'c

tha^'y dda(ng ba`i pho?ng va^'n Nguye^~n Quo^'c Tru.- mo^.t ngu+o+`i co^ng

ta'c vo+'i qui' ba'o- ve^` chuye^'n vie^'ng tha(m Vn cu?a o^ng ta.

Xin qui' ba'o cho bie^'t y' kie^'n ve^` chuye^.n na`y. DDa^y co' pha?i

la` ha`nh ddo^ng tro+? ma(.t ba('t tay vo+'i Cs cu?a NQT hay kho^ng? To^i i't

khi le^n tie^'ng ve^` chuye^.n chi'nh tri. nhu+ng vi` to^i la` ddo^.c gi?a

thu+o+`ng xuye^ng cu?a VHNT online va` ra^'t ye^u me^'n ta.p chi' na`y ne^n

to^i mo+'i le^n tie^'ng.

Xin tha`nh tha^.t ca'm o+n.

Để có được

bài viết của HNH, Gấu phải làm 1 cuộc trở về Hà Nội,

và là người đầu tiên dám mở đường máu,

không đơn giản đâu.

Mang ra hải ngoại, lọ mọ đánh máy, tìm cách

giới thiệu, không chỉ trong giới viết lách mà ra quảng

đại quần chúng qua trang Việt Báo.

Vậy mà không được tên khốn kiếp cám ơn 1 lời.

Không chỉ vờ, mà hắn còn chọc quê GCC, bằng

cách cám ơn HNH.

Ông này ở Hà Nội đâu có biết gì

đâu?

Subject:

Re: Texts

Date: Fri, 8 Dec 2000 10:27:39 -0800

From:

To:

Ca?m o+n anh Tru.

Ba`i Tu+ Tu+o+?ng Gia Ta^n The^' Ky? la` do to^i so't.

DDe^m nay se~ ddi ba`i "Dde^m Tha'nh 3" va` dde^m mai (Thu+' Ba?y) se~

ddi

ba`i Tu+ Tu+o+?ng Gia

To^i phu.c anh kinh khu?ng, ve^` su+' ddo.c, su+'c vie^'t, su+. nha.y

be'n

va` lo`ng tho+ mo^.ng.

Sau na`y ddo^.c gia? trong va` ngoa`i nu+o+'c se~ ghi o+n anh (nhu+

to^i

dda~ no'i ho^`i anh ghe' Calif.),

nha^'t la` gio+'i sinh vie^n va` dda(.c

bie^.t la` gio+'i nha` va(n nhu+ to^i.

Tha^n a'i

PTH Việt Báo

ELEGY FOR A PARK

The labyrinth

has vanished. Vanished also

those orderly avenues of eucalyptus,

the summer awnings, and the watchful eye

of the ever-seeing mirror, duplicating

every expression on every human face,

everything brief and fleeting. The stopped clock,

the ingrown tangle of the honeysuckle,

the garden arbor with its whimsical statues,

the other side of evening, the trill of birds,

the mirador, the lazy swish of a fountain,

are all things of the past. Things of what past?

If there were no beginning, nor imminent ending,

if lying in store for us is an infinity

of white days alternating with black nights,

we are living now the past we will become.

We are time itself, the indivisible river.

We are Uxmal and Carthage, we are the perished

walls of the Romans and the vanished park,

the vanished park these lines commemorate.

-A.R.

J.L. Borges: Poems of the Night

Tập san Văn chương ra mắt độc giả khoảng 1972-74, tại Sài-gòn.

Chết trước ngày 30/ 4/ 75. Hình như là do bác

sĩ kiêm quản lý bất đắc dĩ, Nguyễn Tường Giang, chán

chuyện đi lấy quảng cáo, mặc dù đi là có;

và mặc dù tập san có nhà in riêng -

nhà in ABC của thân phụ anh Phạm Kiều Tùng. Có

lần, trên tạp chí Thơ, tôi đã viết về cái

đức sửa mo-rát, sửa lỗi chính tả của anh. Tôi vẫn

còn nhớ tiểu đề một số tập san, Mặt Trời Mất Đi, Mặt Trời Tìm

Thấy, do anh đề nghị. Bằng tiếng Tây: Soleils Perdus, Soleils Retrouvés.

Đây là một dị ứng, một phản ứng tự vệ, trước sự hiện diện,

không phải với mấy anh chàng Yankee đứng ngơ ngẩn ở ngã

tư đường phố Sài-gòn, tò mò nhìn phố

xá, dòng người qua lại, vào những buổi cuối tuần,

những ngày mới tới, mà là những thay đổi quá

nhanh chóng của thành phố, cùng với sự hiện diện của

họ.

Y hệt như một phim Viễn Tây, trên đường phố Sài-gòn

đang biến dạng.

Note:

Cái anh chàng Yankee mà Gấu nhìn thấy, là

ở góc đường này, từ Quán Chùa

Nhớ hoài!

|

Trang NQT

art2all.net

Lô

cốt

trên

đê

làng

Thanh Trì,

Sơn Tây

|