Obituary: Shimon Peres

Intriguing

for peace: Âm

Mưu Hòa Bường

Shimon Peres, an Israeli statesman, died on September 28th, aged 93

HE OUTLIVED

all his country’s other founding fathers, but failed in what he most yearned

for: to lead it into a lasting peace. Missed opportunities dogged Shimon

Peres’s career. He gained the highest offices—prime minister, twice,

and president—but the political arithmetic invariably went against him.

His forte was foreign policy, but his political nemesis, Menachem Begin,

signed the peace treaty with Egypt in 1979, and his arch-rival, Yitzhak

Rabin, got most of the plaudits for Israel’s deal in 1993 with the Palestinian

leader, Yasser Arafat.

Mr Peres’s

imprint was lasting, nonetheless. As a precocious young civil servant,

he brokered arms deals which helped his uniformed counterparts to get the

weapons they needed. He circumvented arms embargoes with creative ruses,

such as buying warplanes as, purportedly, film props, and cannily found

leaky frigates and rusty tanks in places where they were no longer needed.

He bargained hard, shaming rich countries for charging full price to tiny,

beleaguered Israel, and cajoling rich sympathisers. It meant breaking a

lot of rules. Jimmy Hoffa, boss of America’s Teamsters union, became a

friend, and Israel’s rapprochement with West Germany was cemented with

marathon drinking sessions with the arch-conservative Bavarian, Franz-Josef

Strauss.

Sách

&

Báo

Mới

SOMETHING ABOUT WRITING

IF I'M not mistaken, Balzac,

for example, wrote novels nonstop until the moment that pulled him

out of the practice of his profession. Let us just try and roughly imagine

the extent of such a faculty for fantasizing. For Dostoyevsky, as I

believe I should know, it may have been the same. After publishing a

string of comparatively very worthwhile novellas, Gottfried Keller entered

the civil service, which for the next fifteen years kept him from

any further continuous literary work. Adalbert Stifter, who possessed

a lively talent for narrative like an effervescent spring upon which

he drew to his heart's content, held a civil service post in education.

Goethe, this giant, as his life history displays, poeticized himself

into, as it were, a courrlike, that is, administrative position through

works that soared into the ranks of the imperishable. The existence of

a writer is determined by neither success nor acclaim, but rather depends

on his desire or power to tabulate anew again and again. Balzac apparently

did this constantly, Keller not, and undoubtedly there were reasons why

he didn't. I believe the causes as to why some continue to write on and

on and others at times cease their poetic endeavors are, under certain

circumstances, too subtle to be easily defined. External events are capable

of giving a career a certain direction; for example, the character or incidents

in the region of the heart may be worthy of serious consideration. Some

writers present their best work at the beginning of their strivings only

to succumb afterwards to their proclivity, bit by bit, to flatten out,

while we know of quite a few others who strike us as curious because they

happen to start inconspicuously or uncertainly, but nevertheless precisely

for this reason acquire in the course of time more certitude, superior

vision, etc. To which type one gives preference is left to necessity. Every

writer is an aggregate of two people, the citizen and the artist, to which

he, more or less fortunately, resigns himself.

(1930)

Note: Bài Bạt tuyệt

lắm. Tin Văn sẽ đi liền.

Tác giả bài viết, Tom Whalen nhìn ra 1 Walser

khác hẳn với cách nhìn chung, coi ông cùng

dòng với Musil, Broch hay Thomas Mann, thí dụ.

LI-YOUNG LEE

Folding a Five-Cornered Star

So the Corners Meet

This sadness I feel tonight is not my sadness.

Maybe it's my father's.

For having never been prized by his father.

For having never profited by his son.

This loneliness is Nobody's. Nobody's lonely

because Nobody was never born

and will never die.

This gloom is Someone Else's.

Someone Else is gloomy

because he's always someone else.

For so many years, I answered to a name,

and I can't say who answered.

Mister Know Nothing? Brother Inconsolable?

Sister Every Secret Thing? Anybody? Somebody?

Somebody thinks:

With death for a bedfellow,

how could thinking be anything but restless?

Somebody thinks: God, I turn my hand face down

and You are You and I am me.

I turn my hand face up

and You are the I

and I am your Thee.

What happens when you turn your hand?

Lord, remember me.

I was born in the City of Victory,

on a street called Jalan Industri, where

each morning, the man selling rice cakes went by

pushing his cart, its little steamer whistling,

while at his waist, at the end of a red string,

a little brass bell

shivered into a fine, steady seizure.

This sleeplessness is not my sleeplessness.

It must be the stars' insomnia.

And I am their earthbound descendant.

Someone, Anyone, No one, me, and Someone Else.

Five in a bed, and none of us can sleep.

Five in one body, begotten, not made.

And the sorrow we bear together is none of ours.

Maybe it's Yours, God.

For living so near to your creatures.

For suffering so many incarnations unknown to Yourself.

For remaining strange to lovers and friends,

and then outliving them and all of their names for You.

For living sometimes for years without a name.

And all of Your spring times disheveled.

And all of Your winters one winter.

from Image

SUJI

KWOCK KIM

Return of the Native

****

for Kang,

born in Sonchon, North Korea

Better not to have been born

than to survive everyone you loved.

There's no one left of those who lived here once,

no one to accuse you, no one to forgive you-

only beggar boys or black-market wives

haggling over croakers and cuttlefish,

hawking scrap-iron and copper-pipes stripped from factories

in the shadow of the statue of the Great Leader.

Only streets emptied of the villagers you knew,

only the sound of steps of those no longer living,

ghosts grown old, grim shadows of what they had once been:

some in handcuffs, some in hoods taken away at midnight,

some roped and dragged into Soviet Tsir trucks

driven to the labor camps that "don't exist."

Every absence has a name, a face, a fate:

but who, besides you, remembers they were ever alive?

You don't know why you were spared,

why you breathe walk drink eat laugh weep-

never speaking of those who had been killed,

as if they had never existed, as if the act of surviving

them

had murdered them.

Forget,jorget! But they want to be remembered.

Better people than you were shot:

do you think your life is enough for them?

For the silence

is never silent: it says We hate you

because you survived. No. We hate you

because you escaped.

from Ploughshares

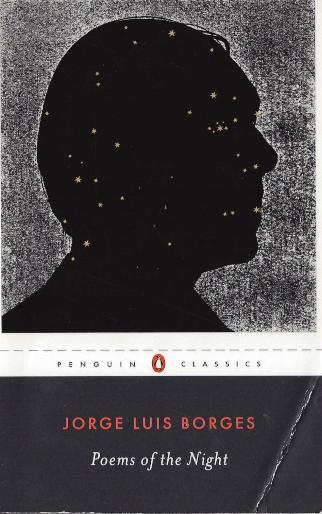

Imaginary Beings

Book

The Sphinx

The Sphinx found on Egyptian monuments

(called "Androsphinx" by Herodotus, to

distinguish it from the Greek creature) is a recumbent

lion with the head of a man; it is believed to represent

the authority of the pharaoh, and it guarded the tombs

and temples of that land. Other Sphinxes, on the avenues

of Karnak, have the head of a lamb, the animal sacred

to Amon. Bearded and crowned Sphinxes are found on monuments

in Assyria, and it is a common image on Persian jewelry. Pliny

includes Sphinxes in his catalog of Ethiopian animals,

but the only description he offers is that it has "brown

hair and two mammae on the breast."

The Greek Sphinx

has the head and breasts of a woman, the

wings of a bird, and the body and legs of a lion. Others

give it the body of a dog and the tail of a serpent.

Legend recounts that it devastated the countryside of

Thebes by demanding that travelers on the roads solve

riddles that it put to them (it had a human voice); it devoured

those who could not answer. This was the famous question

it put to Oedipus, son of Jocasta: "What has four feet, two

feet, or three feet, and the more feet it has, the weaker

it is?" (1)

Oedipus answered

that it was man, who crawls on four legs as

a child, walks upon two legs as a man, and leans

upon a stick in old age. The Sphinx, its riddle solved,

leapt to its death from a mountaintop.

In 1849 Thomas

De Quincey suggested a second interpretation,

which might complement the traditional one.

The answer to the riddle, according to De Quincey,

is less man in general than Oedipus himself, a helpless

orphan in his morning, alone in the fullness of his manhood,

and leaning upon Antigone in his blind and hopeless

old age.

(1)

This is apparently the oldest version

of the riddle. The years have added the

metaphor of the life of man as a single day, so that

we now know the following version of it: "What animal walks

on four legs in the morning, two legs at midday, and three

in the evening?"

Đọc/Viết

mỗi ngày

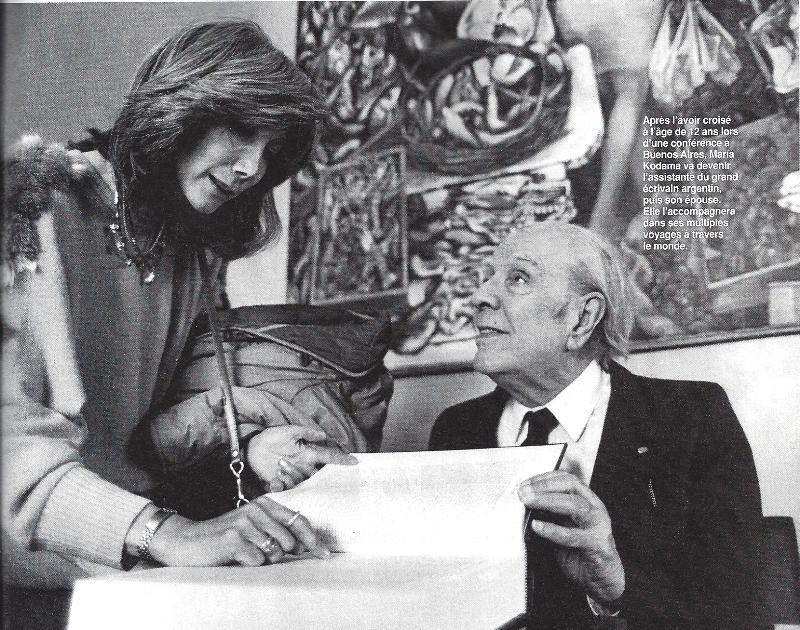

Borges

Conversations

You Only Need To Be Alive:

Art Should Free Itself from Time

OSVALDO FERRARI. Today we will

talk about beauty. But before we do so, we will transcribe your views

about the place of art and literature in our times as discussed in an

earlier conversation.

JORGE LUIS BORGES. Art and literature ... should try and free

themselves from time. Often, I have been told that art depends on politics

or on history. I think that's untrue. It escapes, in some way, from the

organized causality of history. Whether art happens or doesn't, either

depend on the artist.

FERRARI. Another matter not usually talked or thought about,

apart from the spiritual life, is beauty. It's odd that, these days,

artists or writers do not talk about what is supposedly always their

inspiration or objective, that is, beauty.

BORGES. Perhaps the word has been worn out but not the concept-

because what purpose does art have other than beauty? Perhaps the word

'beauty' is not beautiful though the fact is, of course.

FERRARI. Certainly, but in your writing, your poems, your stories

...

BORGES. I try to avoid what's called 'ugly art'- sounds horrible,

doesn't it? But there have been so many literary movements with horrible

names. In Mexico, for example, there was a literary movement frighteningly

called Stridentism. It finally shut up, which was the best thing it could

do. To aspire to be strident-how awkward, isn't it!

My friend Manuel Maples Arce led that movement against the great

poet Ramon Lopez Velarde. I remember his first book-without any hint

of beauty, it was called 'Inner Scaffolding'. That's very awkward isn't

it? (Laughs) To possess inner scaffolding? I remember one

line of a poem, if it was a poem at all: 'A man with tuberculosis has committed

suicide in all the newspapers'. It's the only line I recall. Perhaps my

forgetfulness is kind-if that was the best line in the book, on shouldn't

expect much from the rest of it. I saw him many years later in Japan. I think

he was the Mexican ambassador there and that had made him forget not only

literature but his literature. But he has remained in the histories of literature,

which collects everything, as the founder of the Stridentist movement

(both laugh). Wanting to be strident-one of the most awkward

of literary desires.

FERRARI. As we are talking about beauty, I would like to consult

you about something that has caught my attention. Plato said that of

all the archetypal and supernatural entities, the only visible one on

earth the only manifest one, is beauty.

BORGES. Yes, made manifest through other things.

FERRARI. Caught by our senses.

BORGES. I'm not sure about that.

FERRARI. That's what Plato said.

BORGES. Well, of course, I suppose that the beauty of a poem

has to appeal to our ears and the beauty of a sculpture has to pass

through touch and sight. But these are mediums and nothing more. I don't

know if we see beauty or if beauty reaches us through forms which could

be verbal or sensual or, as in the case of music, auditory. Walter Pater

said that all the arts aspire to the condition of music. I think that

is because form and content fuse in music. That is, one can tell the plot

of a story, perhaps even give it away, or that of a novel, but one cannot

tell the story of a melody, however straightforward it may be. Stevenson

said, though I think he was mistaken, that a literary character is nothing

but a string of words. Well, it is true, but at the same time it's necessary

that we perceive it as more than a string of words.

We must believe in it.

FERRARI. It must, in some way, be real.

BORGES. Yes. Because if we sense that a character is only a string

of words, then that character has not been well created. For example,

reading a novel, we must believe that its characters live beyond what

the author tells us about them. If we think about any character in a novel

or a play, we have to think that this character, in the moment that we

see him, sleeps, dreams and carries out diverse functions. Because if we

don't, then he would be completely unreal.

FERRARI. Yes. There's a sentence by Dostoyevsky that caught my

eye as much as one by Plato. About beauty, he said, 'In beauty, God

and the devil fight and the battlefield is man's heart.'

BORGES. That's very similar to one by Ibsen, 'That life is a

battle with the devil in the grottoes and caverns of the brain and that

poetry is the fact of celebrating the final judgment about oneself.'

It's quite similar, isn't it?

FERRARI. It is. Plato attributes beauty to a destiny, a mission.

And among us, Murena has said that he considers beauty capable of transmitting

an other-worldly truth.

BORGES. If it's not transmitted, if we do not receive it as a

revelation beyond what's given by our senses, then it's useless. I believe

that feeling is common. I have noticed that people are constantly capable

of uttering poetic phrases they do not appreciate. For example, my mother

commented on the death of a very young cousin to our cook from Cordoba.

And the cook said, quite unaware that it was literary, 'But Senora, in order

to die, you only need to be alive.' You only need to be alive! She was unaware

that she had uttered a memorable sentence. I used it later in a story: 'You

only need to be alive'-you do not require any other conditions to die, that's

the sole one. I think people are always uttering memorable phrases without

realizing it. Perhaps the artist's role is to gather such phrases and retain

them. George Bernard Shaw says that all his clever expressions are the ones

he had casually overheard. But that could be another clever feature of Shaw's

modesty.

FERRARI. A writer would be, in that case, a great coordinator

of other people's wit.

BORGES. Yes, let's say, everyone's secretary-a secretary for

so many masters that perhaps what matters is to be a secretary and not

the inventor of the sayings.

FERRARI. An individual memory of a collective.

BORGES. Yes, exactly that.

Bạn chỉ cần còn sống,

và nếu may mắn hơn Y Uyên, bạn sẽ đụng 1 cuộc chiến khác,

khủng khiếp cũng chẳng kém: Văn Chương.

Bạn chỉ cần, chỉ cần,

chỉ cần.... còn sống!

Đám tinh anh Ngụy chết vì câu này.

Chúng chỉ cần còn sống, và tìm đủ mọi cách

để.... bỏ chạy cuộc chiến.

Lũ Triết Mít, sở dĩ chúng chọn Triết, vì

cứ học thuộc lòng cours của Thầy, là đậu, là được

hoãn dịch, là thoát chết.

Rõ ràng là, đám này không

viết được 1 cái gì cho ra hồn, là do phần đạo hạnh

của chúng có 1 vết chàm to tổ bố, làm sao

viết?

Mỹ là Mẹ của Đạo Hạnh. Đạo Hạnh có vết chàm

làm sao có Mỹ?

Rồi đám bỏ cuộc chiến bằng con đường du học, cũng Mắm Sốt

Kít!

Ferrari:

Dos phán, trong cái đẹp Chúa và Quỉ uýnh

lộn và chiến trường là trái tim của con người

Borges. Giống câu của Ibsen, Đời là cuộc chiến với

quỉ, ở hang cùng ngõ hẻm của cục não của con người

và thơ là sự lên ngôi của Phán Quyết

Chót của 1 con người về chính nó.

Đúng thế. Plato gán cái đẹp, cho số phần,

cho nhiệm vụ. Và giữa chúng ta, Murena phán, cái

đẹp có thể chuyên chở một sự thực “khác”

Trong cuốn tiểu luận nho nhỏ trên,

đa số là những phê bình, nhận định, điểm

sách, có hai bài viết về tuổi thơ, phải

nói là tuyệt cú mèo. Tin Văn sẽ post,

và lai rai ba sợi về chúng.

Bài “Tuổi thơ đã mất”,

The Lost Childhood, viết về những cuốn sách mà

chúng ta đọc khi còn con nít. “Gánh

nặng tuổi thơ”, theo Gấu, tuyệt hơn, phản ứng của con người,

ở đây, là ba nhà văn hách xì

xằng, về thời thơ ấu khốn khổ khốn nạn của họ, và bằng cách

nào, họ hất bỏ gánh nặng này.

Khi Gấu trở về lại Đất Bắc, Gấu

thấy mình giống như một kẻ đi tìm gặp một

thằng Gấu còn ở lại Đất Bắc, và, tìm hiểu,

bằng cách nào thằng Gấu đó hất bỏ được gánh

nặng tuổi thơ…

L' Appel Du Mort

Lướt

TV

http://www.tanvien.net/Ky/Hay_doi_hay_dien.html

Ðuốc Tình

Có

một người con gái rất trẻ

hỏi một người phụ nữ lớn tuổi

Đàn ông yêu như thế nào

họ yêu có khác mình không?

Người

phụ nữ ngẫm nghĩ

Tình yêu của đàn ông à?

Lạ lắm

nói thế nào cho đúng nhỉ

Thế

này nhé

Đó là một ngày

bỗng dưng

có một người đàn ông ở đâu đến

một tay cầm bó đuốc

tay kia gõ gõ lên cánh cửa hồn

mình

ngọn đuốc

cháy phừng phừng

tưởng như không có cách nào dập

tắt được

Anh

ta quơ quơ ngọn đuốc

linh hồn mình bắt cháy

thành than

Anh ta ghé xuống

sưởi cả thân thể ấm áp của riêng anh

xong

bỏ đi

quên ngay ngọn lửa

Và

đàn bà

thì muôn thủa

tiếc ngọn lửa đã đốt cháy hồn mình

thu những tàn tro

phủ lên những mảnh than còn sót lại

cố che chắn giữ cho đốm lửa âm ỉ

tự sưởi một phần đời

Cho

dù có một ngọn lửa khác đốt lên

hong ấm lại nàng

những mảnh than đầu tiên

vẫn không bao giờ tắt

Đó

là sự khác biệt về tình yêu

giữa đàn ông và đàn bà.

TMT

Note:

Bài thơ, đăng trên DM, có 1 lỗi đánh

máy, GCC chờ hoài, coi có ai nhận ra.

Nô là Nô.

Thơ bị coi rẻ là vậy.

Một cái dấu phảy thôi, mà có

thế giới, chết vì nó, như Cioran đã từng mơ tưởng.

GCC sợ rằng, chính tác

giả của bài thơ cũng coi rẻ nó.

NMG phán về GCC, ông

ưa cầu toàn, vì cái tật, vừa gửi text đi, là

đã gửi tiếp text revised liền tù tì theo rồi.

Hồi GCC còn quan hệ thân

thiết với đám bạn văn VC, có 1 em nhận xét,

vừa nhận 1 bài viết của anh, đã có liền bài

revised, chỉ khác bài trước, đúng 1 cái

dấu phảy!

Hà, hà!

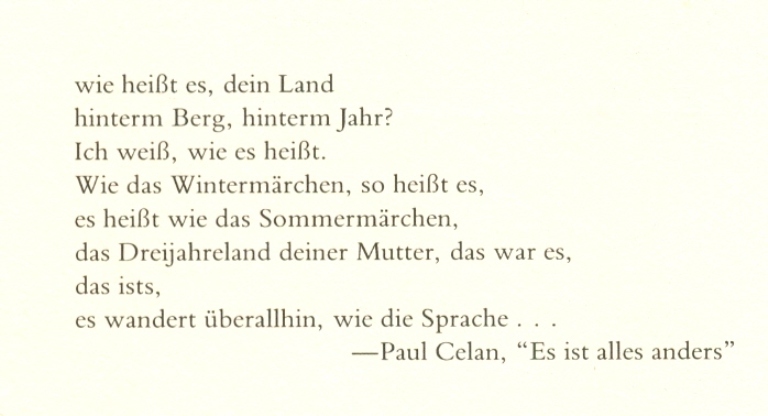

Gọi là

gì, xứ của anh?

Sau núi, sau năm?

Tôi biết, gọi là gì

Chuyện mùa đông, nó được gọi

Nó được gọi, chuyện mùa hè

Ba năm mẹ già (1) cũng đừng trông, nó

là thế

Thế nó là

Nó lang thang khắp nơi

Như ngôn ngữ

(1) Người

đi, ừ nhỉ người đi thực

Ba năm mẹ già cũng đừng trông

Thâm Tâm: Tống Biệt Hành

Là

cái gì, chuyện 1 bản văn (hay bất cứ cái chi

chi) cưỡng lại cố gắng của chúng ta khi làm cho nó

có nghĩa?

Về câu hỏi này, những bản viết của George Steiner

có vẻ như chỉ đúng hướng cho chúng ta. Câu

hỏi phơi bày cho chúng ta, tới cái kinh nghiệm

cơ bản của người dịch thuật, mà người ta có thể tóm

gọn, và nói, đây là thứ kinh nghiệm có

trước tất cả mọi kinh nghiệm, kinh nghiệm về không-căn cước, hay

về cái cá thể tối giản, hết còn đơn giản được nữa,

của mọi hiện hữu, đặc biệt là về con người và ngôn

ngữ của nó. Kinh nghiệm này thì vừa đạo hạnh, vừa

mở, nghĩa là không bao giờ chấm dứt.

Một bên thì cố gắng làm cho bên

kia trở thành thông suốt, ở bên trong ngôn

ngữ, khung văn hóa của riêng nó, nhưng bên

kia không thể nào bị khách hoá, đối tượng

hóa, theo cái kiểu này, bởi vì nó

thuộc về thế giới của riêng nó, và không

thể nào bị đánh gốc, bật rễ ra khỏi nếu không dùng

bạo lực. Cổ đại Latinh hiểu rõ điều này, khi gắn kết dịch

thuật với những chiến thắng thành phố, bắt nô lệ, và

khuân của cải về nhà – nói ngắn gọn, sự hình

thành đế quốc.

Cái

em nhà quê tuy lớn lên ở ngoài này,

đâu có hiểu rằng là, khi dịch ba thứ văn thơ ăn

cướp của VC, là cũng góp phần kiện toàn Cái

Ác Bắc Kít.

[Sorry DTBT. NQT]

Không phải tự nhiên

mà TV lại giới thiệu những tác giả như W.G. Sebald.

Cũng thế, phản ứng của 1 anh bạn văn VC ở Hà Nội,

sao cứ lải nhải hoài về Lò Thiêu, mắc mớ gì

đến Mít.

Hay của 1 độc giả TV, mi bị THNM rồi, nhìn đâu

cũng thấy VC.

May mà có em BHD, không thì mi

biến thành quỉ VC từ khuya rồi!

Cũng thế, không phải tự

nhiên “em” DTBT, ưa mơ mộng, thích vượt khoảng trống

dịch thơ LTMD, người đẹp của HPNT, thí dụ.

Trong bài phỏng vấn, do khả năng chắc cũng hơi hạn

hẹp của cả hai, cho nên chẳng người nào đề cập đến sự

nguy hiểm của dịch dọt.

Nếu không bị đám

khốn xúm lại đánh, [ngay khi Chợ Cá vừa xuất

hiện. Trận đòn hội chợ này có sự tiếp tay của

Sến. Em giả đò thương hại, khi có vài độc giả lên

tiếng bênh Gấu, sao anh không chịu đích thân

trả lời, hết xí oát rồi hả…], thì Gấu đã tiếp

tục loạt bài về dịch cho talawas.

SCN lúc đầu rất mừng, liền sau khi đọc bài

đầu Gấu gửi. Em viết mail, trước giờ, viết sâu sắc, nhưng bài

này, Dịch

Là Cướp,

cho thấy khía cạnh tức cười…. Gấu đã tính đi 1 loạt

bài cho CC.

Cái tít của Sến, của Gấu dài thòng.

SCN rất có tài đặt tít. Thật gọn, thật

nổi. Cái tít “Miếng Cơm Manh Chữ” cũng của Sến

Nay nhân cơ hội, viết

tiếp.

Trước hết, giới thiệu bài của Gerald L. Bruns

Về Cái Khó, On Difficulty: Steiner, Heidegger, and

Paul Celan

Trong Ðọc Steiner,

Reading George Steiner.

Cuốn này của NTV cho

GCC, ngay những ngày mới ra hải ngoại, khi thấy GCC mê Steiner

quá!

Anh cho biết, đọc Steiner từ Việt Nam, trước 1975, tại Sài

Gòn, cuốn Ngôn ngữ và Câm lặng,

nhưng không bị choáng như GCC.

Và kết luận, mi phải có Cái Ác

Bắc Kít, và nó phải thật đậm đặc đến nỗi, vừa

gặp… Cái Ác Nazi và Lò Thiêu,

là nó bùng bổ ra.

Cốm là 1 đặc sản của

Mít, nó đâu có từ đương đương để mà dịch

qua tiếng Anh?

Cũng thế, những từ “phanh”, lốp [xe], xà phòng

của Tây mũi lõ, mà dân Mít mượn.

Ðâu chỉ 1 từ cốm. Những từ áo dài,

cái nhà, nước mắm, con gái… mũi lõ chỉ

nội nghe đọc lên, là đã thèm nhỏ nước miếng

rồi.

Vậy mà dám dịch là “green rice”, thì

đúng là hiếp dâm… cốm!

Em này do sống ở ngoài này, thành

ra chưa từng nhìn thấy cái gọi là green rice,

thứ gạo hẩm, lên men xanh, bốc mùi hôi, mà

nhờ VC Bắc Kít giải phóng Miền Nam, dân Miền Nam mới

nhìn thấy và được thưởng thức.

Em cũng bày đặt mê tiếng thơ át tiếng

bom, thành ra mới dịch thơ của người đẹp và con thú

LTMD, mới dịch cái gì gì “Đạn bom rơi chẳng sợ đâu/

Chỉ e sương ướt mái đầu lá chanh", mà DTBT dịch

“We are not frightened by bullets and bombs in the air/Only by dew wetting

our lime-scented hair”, “Tình Sầu” thành “Meditations

on Love”… thật tội nghiệp cho chữ nghĩa Việt Nam quá chừng!!!

[Trích 1 cái còm của một độc giả trên DM].

Ðây là ăn phải Kít WJC.

Hay có thể, cũng nhắm đường về rồi.

*

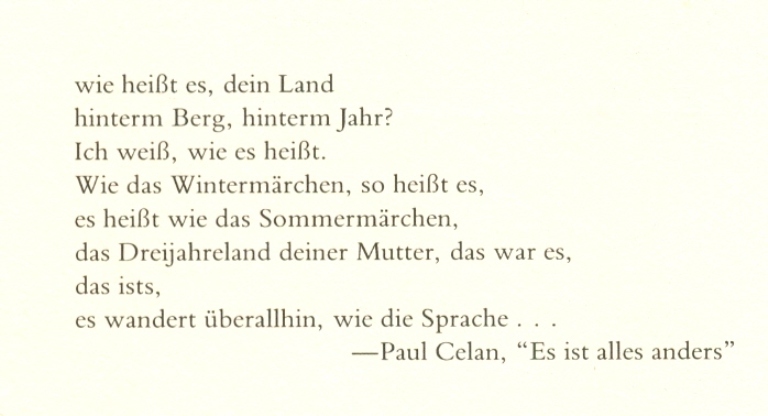

GERALD L. BRUNS

On Difficulty: Steiner, Heidegger,

and Paul Celan

what is it called, your country

behind the mountain, behind

the year?

I know what it's called.

Like the winter's tale,

it is called,

it's called like the summer's tale,

your mother's threeyearland,

that's what it was,

what it is,

it wanders off everywhere,

like language.

Gọi là gì, xứ của

anh?

Sau núi, sau năm?

Tôi biết, gọi là gì

Chuyện mùa đông, nó được gọi

Nó được gọi, chuyện mùa hè

Ba năm mẹ già (1) cũng đừng trông, nó

là thế

Thế nó là

Nó lang thang khắp nơi

Như ngôn ngữ

(1) Người đi, ừ nhỉ người đi

thực

Ba năm mẹ già cũng đừng trông

Thâm Tâm: Tống

Biệt Hành

ALEXIS RHONE FANCHER

When I turned fourteen,

my mother's sister took me

to lunch and said:

***

soon you'll have breasts. They'll mushroom on your

smooth chest like land mines.

A boy will show up, a schoolmate, or the gardener's son.

Pole-cat around you. All brown-eyed persistence.

He'll be everything your parents hate, a smart aleck,

a dropout, a street racer on the midnight prowl.

Even your best friend will call him a loser.

But this boy will steal your reason, have you

writing his name inside a scarlet heart, entwined

with misplaced passion and a bungled first kiss.

He'll bivouac beneath your window, sweet-talk you

until you sneak out into his waiting complications.

Go ahead, tempt him with your new-found glamour.

Tumble into the backseat of his Ford at the top of Mulholland,

flushed with stardust, his mouth in a death-clamp on your

nipple,

his worshipful fingers scatting sacraments on your clit.

Soon he will deceive you with your younger sister,

the girl who once loved you most in the world.

from Ragazine

From The Best

American Poetry 2016

Note:

Đọc song song với Đuốc Tình

|

Trang NQT

art2all.net

Lô

cốt

trên

đê

làng

Thanh Trì,

Sơn Tây

|