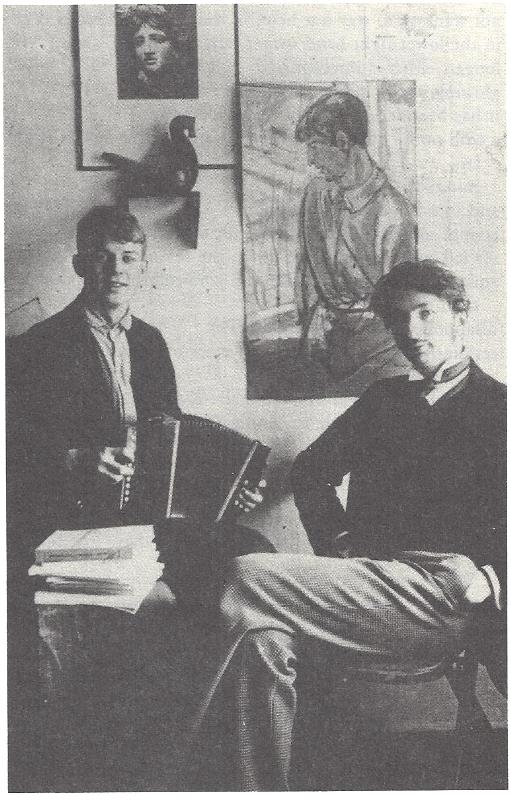

2 Looking on a Russian Photograph, 1928/1995 Chân Dung Nga |

Sergei Yesenin Not very

deep in the well of the past, but over twenty years ago, I wrote a book

called

Letters to Yesenin, actual letters in the form of poems addressed to

Yesenin

because I was so far in extremis that I could think of no one else

appropriate,

somewhat in the manner of children who for periods can only communicate

with

imaginary friends. What a bloody voyage before and since. But then it

couldn't have

been otherwise because that is what happened, and given enough energy

we tend

to evolve into what we actually are. The poems I wrote are still

largely

unbearable to me, and perhaps should be made into wallpaper for a

psychoanalyst's office. I wrote Yesenin as a brother who had visited

his death scene

in St. Petersburg on a nasty hangover on a very cold autumn day, then

took a

long walk along the Nevsky Prospect to figure it out. But then the

burden of

the incomprehensible is still there. Despite all the tripery about

"healing" we are permanently inconsolable, and to be less so would

dishonor life. Now, at this moment, looking at the photo of Yesenin

holding the

concertina, there is a jolt of melancholy caused by his expectant grin.

His

soul kept saying "a good time should be had by all." He crossed the

fragile line between expecting nothing and wanting everything. He could

never

put out the fire in his hair. This young man drew water, milked cows,

chopped

wood, picked mushrooms, then went to the city as we all must, but never

really

went back home. His fabulous vices took him early, and it is not proper

for us

like some dweedling Greek chorus to pity him any more than we should

Dylan

Thomas, his cousin. He is Yesenin and he gave voice to the gods in him

to keep

them alive. You must remember, after all, that he is Yesenin. We shall

hear his

music until the planet dies.

-Jim

HarrisonChân Dung Nga  Sergei Yesenin Not very

deep in the well of the past, but over twenty years ago, I wrote a book

called

Letters to Yesenin, actual letters in the form of poems addressed to

Yesenin

because I was so far in extremis that I could think of no one else

appropriate,

somewhat in the manner of children who for periods can only communicate

with

imaginary friends. What a bloody voyage before and since. But then it

couldn't have

been otherwise because that is what happened, and given enough energy

we tend

to evolve into what we actually are. The poems I wrote are still

largely

unbearable to me, and perhaps should be made into wallpaper for a

psychoanalyst's office. I wrote Yesenin as a brother who had visited

his death scene

in St. Petersburg on a nasty hangover on a very cold autumn day, then

took a

long walk along the Nevsky Prospect to figure it out. But then the

burden of

the incomprehensible is still there. Despite all the tripery about

"healing" we are permanently inconsolable, and to be less so would

dishonor life. Now, at this moment, looking at the photo of Yesenin

holding the

concertina, there is a jolt of melancholy caused by his expectant grin.

His

soul kept saying "a good time should be had by all." He crossed the

fragile line between expecting nothing and wanting everything. He could

never

put out the fire in his hair. This young man drew water, milked cows,

chopped

wood, picked mushrooms, then went to the city as we all must, but never

really

went back home. His fabulous vices took him early, and it is not proper

for us

like some dweedling Greek chorus to pity him any more than we should

Dylan

Thomas, his cousin. He is Yesenin and he gave voice to the gods in him

to keep

them alive. You must remember, after all, that he is Yesenin. We shall

hear his

music until the planet dies.

-Jim

Harrison  Winter 1995: Một trong những số báo

đầu tiên của

GCC, April, 98. Trong có bài phỏng vấn Steiner. Bèn chơi liền!

Ba bài thơ của Simic, là tìm đọc sau đó. Đã post & dịch trên Tin Văn, Và "Chân Dung Nga". Bài dưới đây, cũng trong số báo nói trên: De Iuventute When I was a

young man Now that I'm

old and

girls will have none of me I must try to imagine what it would have been like with each of them if I had taken some pains to learn to please them. James Laughlin De Iuventute

Khi tớ còn trẻ Mê săn gái Mỗi lần vớ được một em Là hăm hở như... Trâu Nước Hết em này tới em khác! Về già, thua! Và tớ phải cố tưởng tượng Giả như còn, thì Phải cố mà học cho bằng được Nỗi đau Khi hầu hạ em! Shadow

Publishing Company

Trong số báo, còn 1 kỷ

niệm, của 1 tác giả, về lần gặp Beckett, cũng thật tuyệt. Đã giới thiệu

trên TV

Barney

Rosset, the founder of the Grove Press in the early fifties as well as

the

distinguished literary and political magazine, the Evergreen Review

(both

institutions published Samuel Beckett's earliest work) lives and works

in a

Greenwich Village walk-up where he now publishes the Blue Moon Press.

The

offices are a long way up -four flights. On the third floor is a

loft-like

room. At the far end is a Ping-Pong table with one end up on its hinges

so that

half the table faces the player like a backboard. Rosset goes down

there on

occasion and practices. INTERVIEWER - George

Plimpton The Paris

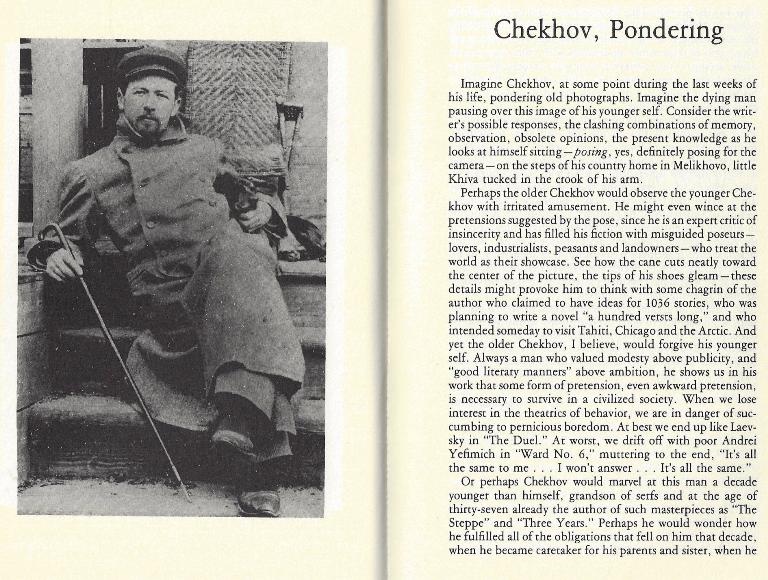

Review,Winter 1995 Beckett là 1 người quân tử. Tôi nghĩ người ta phịa ra từ này, vì có ông ở trên cõi đời này.... Ui chao, vậy mà lại nhớ Quận Cam, nhớ bạn hiền. Mới nhận mail NDT, cho biết bà xã về VN, mấy tuần, sao Gấu không qua, buồn quá! Chúc Mừng Năm Mới. Take Care Please NQT Chekhov,

Pondering Imagine

Chekhov, at some point during the last weeks of his life, pondering old

photographs. Imagine the dying man pausing over this image of his

younger self.

Consider the writer's possible responses, the clashing combinations of

memory,

observation, obsolete opinions, the present knowledge as he looks at

himself

sitting -posing, yes, definitely posing for the camera-on the steps of

his

country home in Melikhovo, little Khiva tucked in the crook of his arm.

Perhaps

the older Chekhov would observe the younger Chekhov with irritated

amusement.

He might even wince at the pretensions suggested by the pose, since he

is an

expert critic of insincerity and has filled his fiction with misguided

poseurs-

lovers, industrialists, peasants and landowners-who treat the world as

their

showcase. See how the cane cuts neatly toward the center of the

picture, the

tips of his shoes gleam-these details might provoke him to think with

some

chagrin of the author who claimed to have ideas for 1036 stories, who

was

planning to write a novel "a hundred versts long," and who intended

someday to visit Tahiti, Chicago and the Arctic. And yet the older

Chekhov, I

believe, would forgive his younger self. Always a man who valued

modesty above

publicity, and "good literary manners" above ambition, he shows us in

his work that some form of pretension, even awkward pretension, is

necessary to

survive in a civilized society. When we lose interest in the theatrics

of

behavior, we are in danger of succumbing to pernicious boredom. At best

we end

up like Laevsky in "The Duel." At worst, we drift off with poor

Andrei Yefimich in "Ward No.6," muttering to the end, "It's all

the same to me ... I won't answer ... It's all the same." Or perhaps

Chekhov would marvel at this man a decade younger than himself,

grandson of

serfs and at the age of thirty-seven already the author of such

masterpieces as

"The Steppe" and "Three Years." Perhaps he would wonder how

he fulfilled all of the obligations that fell on him that decade, when

he

became caretaker for his parents and sister, when he served as the

doctor for

the local peasants and as squire of the village of Melikhovo and still

managed

to make the grueling trip across Siberia to the island of Sakhalin. He

might

recall his pattern of responsible moderation with more than a little

pride,

seeing in this portrait a man who devoted himself to the problems of

others and

yet could come close himself in his study for hours at a time, pick up

his pen

and hear the grass singing in his mind. It could be, though, that the

dying

Chekhov would neither wince nor marvel at this picture but turn away in

despair, comprehending more fully than ever before his own dishonesty.

Here is

Dr. Chekhov, villain of self-deception. What did it matter that he

suffered his

first bout of blood-spitting in 1884, shortly after graduating from

medical

school? What did it matter that for thirteen years, though he treated

many

victims of tuberculosis, he refused to identify the symptoms in

himself? The

disease probably would have progressed at the same speed even had he

sought

treatment earlier. But the lack of acknowledgement is troubling. If

he'd been one

of his characters, his pose of health would have revealed itself as a

lie, and

he would have seemed pathetic in his stubborn effort to make a lasting

name for

himself. Of course, this Chekhov, the Chekhov lounging on the steps of

his

Melikhovo home, collar turned up just so, will be remembered: as the

jaunty,

brilliant writer, as the modest poseur and as a dying man unable to

acknowledge

his illness because the telling would have made death sensible. He

preferred to

tell of life.

-Joanna

Scott

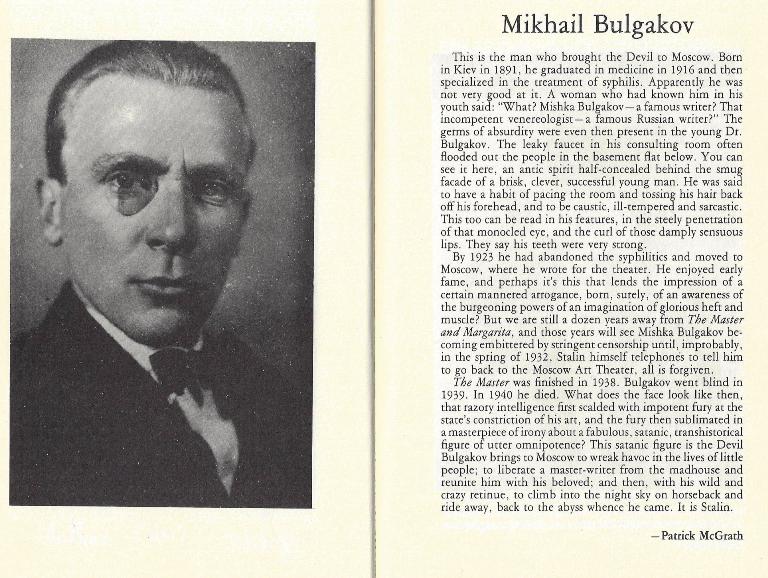

Mikhail

Bulgakov This is the

man who brought the Devil to Moscow. Born in Kiev in 1891, he graduated

in

medicine in 1916 and then specialized in the treatment of syphilis.

Apparently

he was not very good at it. A woman who had known him in his youth

said:

"What? Mishka Bulgakov- a famous writer? That incompetent

venereologist- a famous Russian writer?" The germs of absurdity were

even

then present in the young Dr. Bulgakov. The leaky faucet in his

consulting room

often flooded out the people in the basement flat below. You can see it

here,

an antic spirit half-concealed behind the smug facade of a brisk,

clever,

successful young man. He was said to have a

habit of pacing the room and tossing his hair back off his forehead,

and to be

caustic, ill-tempered and sarcastic. This too can be read in his

features, in

the steely penetration of that monocled eye, and the curl of those

damply

sensuous lips. They say his teeth were very strong. - Patrick

McGrath Tay này đem

Quỉ tới Hà Lội - ấy chết xin lỗi – Mút Ku. Sinh năm 1891, học y khoa,

ra trường

năm 1916, chuyên trị tim la. Có vẻ như ông đếch biết gì về bịnh này, hà

hà! Một

bà biết ông từ khi còn thanh niên, phán, “Cái gì? Mishka Bulgakov? Cái

tên bác sĩ vô tài bất tướng, chẳng biết tí gì về giang mai, hột xoài mà

là nhà

văn Nga Xô nổi tiếng ư?  Winter 1995: Một trong những số báo

đầu tiên của

GCC, April, 98. Trong có bài phỏng vấn Steiner. Bèn chơi liền! Charles Simic Against Winter The truth is dark under

your eyelids. A meek little lamb you

grew your wool Winter coming. Like the

last heroic soldier The Paris Review, Issue 137,1995 Chống Đông Sự thực thì mầu xám dưới

mi mắt anh Con cừu nhỏ, anh vỗ béo bộ

lông của anh Mùa Đông tới. Như tên lính

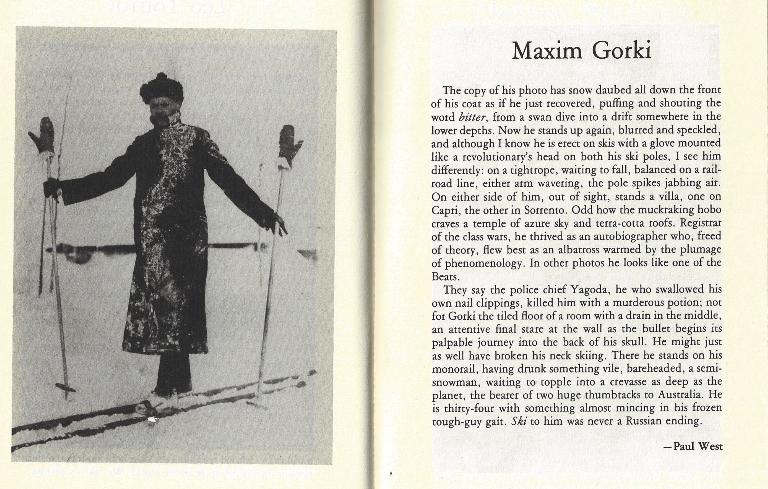

anh dũng cuối cùng  The portraits that follow are from a large number of photographs recently recovered from sealed archives in Moscow, some-rumor has it-from a cache in the bottom of an elevator shaft. Five of those that follow, Akhmatova, Chekhov (with dog), Nabokov, Pasternak (with book), and Tolstoy (on horseback) are from a volume entitled The Russian Century, published early last year by Random House. Seven photographs from that research, which were not incorporated in The Russian Century, are published here for the first time: Bulgakov, Bunin, Eisenstein (in a group with Pasternak and Mayakovski), Gorki, Mayakovski, Nabokov (with mother and sister), Tolstoy (with Chekhov), and Yesenin. The photographs of Andreyev, Babel, and Kharms were supplied by the writers who did the texts on them. The photograph of Dostoyevsky is from the Bettmann archives. Writers who were thought to have an especial affinity with particular Russian authors were asked to provide the accompanying texts. We are immensely in their debt for their cooperation. The Paris

Review Winter 1995 Chân Dung

Nga Những bức

hình sau đây là từ một lố mới kiếm thấy, từ những hồ sơ có đóng mộc ở

Moscow, một

vài bức có giai thoại riêng, thí dụ, đã được giấu kỹ trong ống thông

hơi ở tận

đáy thang máy! Năm trong số, Akhmatova, Chekhov [với con chó], Nabokov,

Pasternak (với sách), và Tolstoy (cưỡi ngựa), từ một cuốn có tên là Thế

Kỷ Nga,

xb cuối năm ngoái [1997], bởi Random House. Bẩy trong cuộc tìm kiếm đó

không được

đưa vô cuốn Thế Kỷ Nga, và được in ở đây, lần thứ nhất: Bulgakov,

Bunin,

Eisenstein (trong một nhóm với Pasternak and Mayakovski), Gorki,

Mayakovski,

Nabokov (với mẹ và chị/em) Tolstoy (với Chekhov), and Yesenin. Hình

Andreyev,

Babel, và Kharms, do những nhà văn kiếm ra cung cấp, kèm bài viết của

họ về chúng.

Hình Dostoyevsky, từ hồ sơ Bettmann. Những nhà văn nghe nói có giai

thoại, hay

mối thân quen kỳ tuyệt về những tác giả Nga, thì bèn được chúng tôi yêu

cầu, viết

đi, viết đi, và chúng tôi thực sự cám ơn họ về mối thịnh tình, và món

nợ lớn

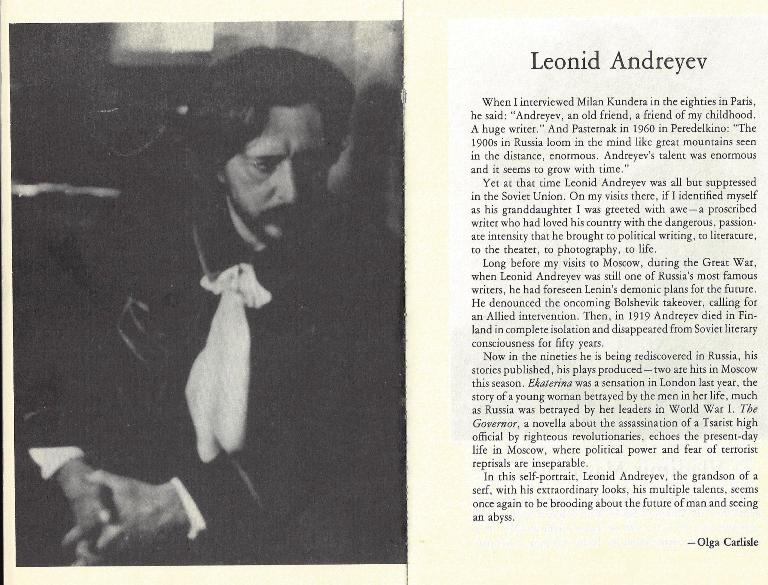

này.  Khi tôi phỏng

vấn Milan Kundera vào thập niên 80 ở Paris, ông nói, “Andreyev, một bạn

cũ, thời

niên thiếu. Nhà văn bự". Bây giờ, vào thập niên 90,

ông lại được khám phá ra, ở Nga,

những truyện của ông được xb, kịch được được dựng – hai, “hits”, ở

Moscow, mùa này. Ekaterina là một “xăng

xa xườn” – sensation, ấn tượng, xúc động (?), ở Luân Đôn, năm ngoái,

câu

chuyện

một em Nga, trẻ, bị những đấng đàn ông trong đời em phản bội, chẳng

khác gì lũ

VC Liên Xô phản bội nhân dân của nó, trong Đệ Nhất Thế Chiến. Viên Tổng Trấn, là

1 truyện ngắn về cú ám sát một viên chức cao cấp của Nga Hoàng, bởi

những người

cách mạng chân chính, làm vọng lên không khí những ngày này ở Moscow,

nơi quyền

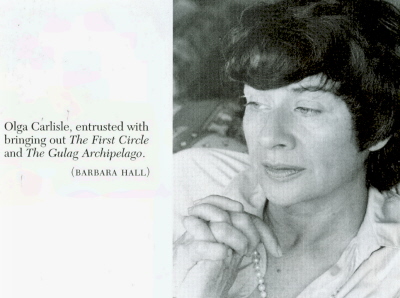

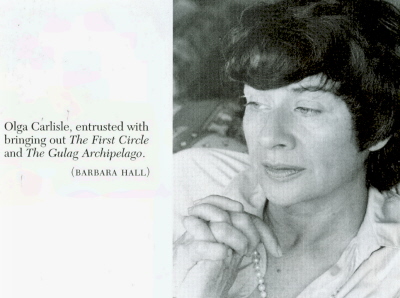

lực chính trị, và nỗi sợ khủng bố trả thù, thì không thể chia lìa. Olga Carlisle [Người được

Solzhenitsyn tin cẩn, lén đem “Quần Đảo Gulag” qua Tây Phương]

Chân Dung Nga

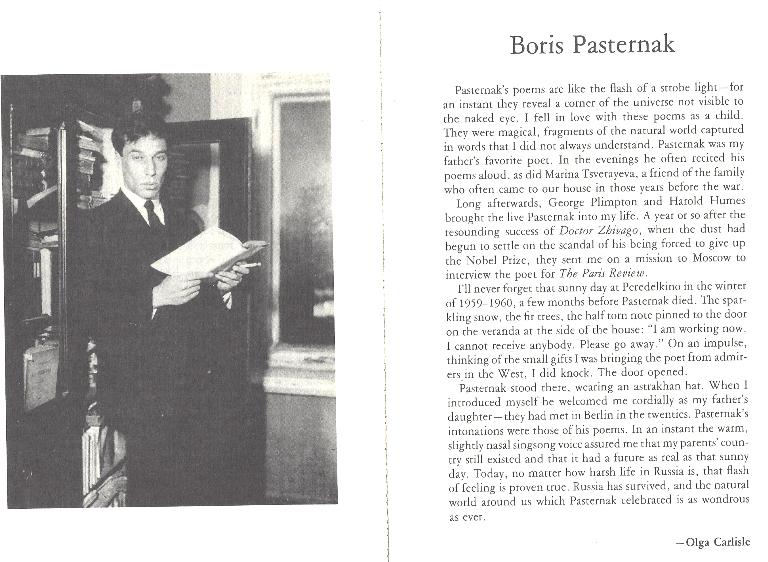

Boris

Pasternak

Pasternak's

poems are like the flash of a strobe light-for an instant they reveal a

corner

of the universe not visible to the naked eye. I fell in love with these

poems

as a child. They were

magical, fragments of the natural world captured in words that I did

not always

understand. Pasternak was my father's favorite poet. In the evenings he

often

recited his poems aloud, as did Marina Tsvetayeva, a friend of the

family who

often came to our house in those years before the war.  Người lén

đem tác phẩm của Solz qua Tây phương Đọc bài viết

1 phát, thì cái đầu óc bịnh hoạn của Gấu Cà Chớn lại hiện ra cái cảnh 1

nhà thơ

hải ngoại, đi cùng, cũng 1 nhà thơ hải ngoại - bạn của GCC, nhưng còn

là cựu sĩ

quan VNCH, bỏ chạy kịp trước 30 Tháng Tư 1975, không có lấy 1 ngày cải

tạo làm

thưốc chữa bịnh lưu vong - bèn bò về, xin yết kiến nhà thơ HC, và

1 ông châm cái đóm, hầu

thuốc lào

nhà thơ số 1 Đất Bắc! Và nhà thơ

HC bèn an ủi hai nhà thơ hải ngoại, quê hương của chúng ta vưỡn còn! Notes About Brodsky Trong một tiểu luận, Brodsky

gọi Mandelstam là một thi sĩ của văn

hóa. Brodsky chính ông, cũng là 1 thi sĩ của văn hóa, và hẳn là vì lý

do này,

ông tạo sự hài hòa với dòng sâu thẳm của thế kỷ, trong đó con người, bị

đe dọa

mất mẹ cái giống người, khám phá ra quá khứ như là một mê cung chẳng hề

có tận

cùng. Lặn sâu vô mê cung, chúng ta khám phá ra cái gì sống sót quá khứ

là kết

quả của nguyên lý phân biệt dựa trên đẳng cấp. Mandelstam, ở trong

Gulag, điên

khùng bới đống rác tìm đồ ăn, [ui chao lại nhớ Giàng Búi], là thực tại

về độc

tài bạo chúa và sự băng hoại thoái hoá bị kết án phải tuyệt diệt.

Mandelstam

đọc thơ cho vài bạn tù là khoảnh khoắc thần tiên còn hoài hoài Bài viết Sự quan trọng của

Simone Weil cũng quá tuyệt. Bắc Kít, chỉ có thứ nhà văn nhà

thơ viết dưới ánh sáng của Đảng! Cái vụ Tố Hữu khóc Stalin thảm

thiết, phải mãi gần đây Gấu mới

giải ra được, sau khi đọc một số bài viết của những Hoàng Cầm, Trần

Dần, những

tự thú, tự kiểm, sổ ghi sổ ghiếc, hồi ký Nguyễn Đăng Mạnh... Sự hèn

nhát của sĩ

phu Bắc Hà, không phải là trước Đảng, mà là trước cá nhân Tố Hữu. Cả xứ

Bắc Kít

bao nhiêu đời Tổng Bí Thư không có một tay nào xứng với Xì Ta Lin.

Mà, Xì,

như chúng ta biết, suốt đời mê văn chương, nhưng không có tài, tài văn

cũng

không, mà tài phê bình "như Thầy Cuốc", lại càng không, nên đành đóng

vai

ngự sử

văn đàn, ban phán giải thưởng, ra ơn mưa móc đối với đám nhà văn, nhà

thơ. Ngay

cả cái sự thù ghét của ông, đối với những thiên tài văn học Nga như

Osip

Mandelstam, Anna Akhmatova… bây giờ Gấu cũng giải ra được, chỉ là vì

những

người này dám đối đầu với Stalin, không hề chịu khuất phục, hay "vấp

ngã"! [Trung nhưng biến thành Bắc Kít]

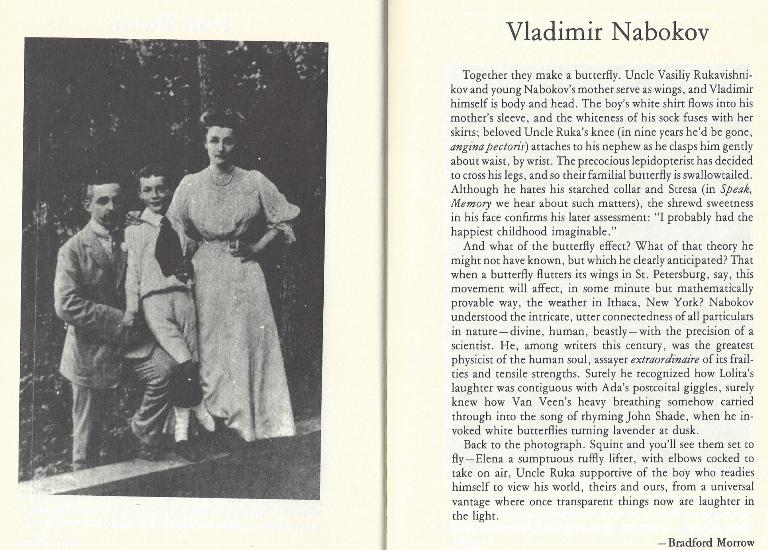

Vladimir Nabokov Together

they make a butterfly. Uncle Vasiliy Rukavishnikov and young Nabokov's

mother

serve as wings, and Vladimir himself is body and head. The boy's white

shirt

flows into his mother's sleeve, and the whiteness of his sock fuses

with her skirts;

beloved Uncle Ruka's knee (in nine years he'd be gone, angina

pectoris) attaches to his nephew as he clasps him gently about

waist, by wrist. The precocious lepidopterist has decided to cross his

legs,

and so their familial butterfly is swallow-tailed. Although he

hates his starched collar and Stresa (in Speak,

Memory we hear about such matters), the shrewd sweetness in his

face

confirms his later assessment: "I probably had the happiest childhood

imaginable." And what of

the butterfly effect? What of that theory he might not have known, but

which he

clearly anticipated? That when a butterfly flutters its wings in St.

Petersburg, say, this movement will affect, in some minute but

mathematically provable

way, the weather in Ithaca, New York? Nabokov understood the intricate,

utter

connectedness of all particulars in nature-divine, human, beastly -with

the

precision of a scientist. He, among writers this century, was the

greatest physicist

of the human soul, assayer extraordinaire

of its frailties and tensile strengths. Surely he recognized how

Lolita's laughter

was contiguous with Ada's postcoital giggles, surely knew how Van

Veen's heavy

breathing somehow carried through into the song of rhyming John Shade,

when he

invoked white butterflies turning lavender at dusk. Back to the

photograph. Squint and you'll see them set to fly-Elena a sumptuous

ruffly

lifter, with elbows cocked to take on air, Uncle Ruka supportive of the

boy who

readies himself to view his world, theirs and ours, from a universal

vantage

where once transparent things now are laughter in the light. -Bradford

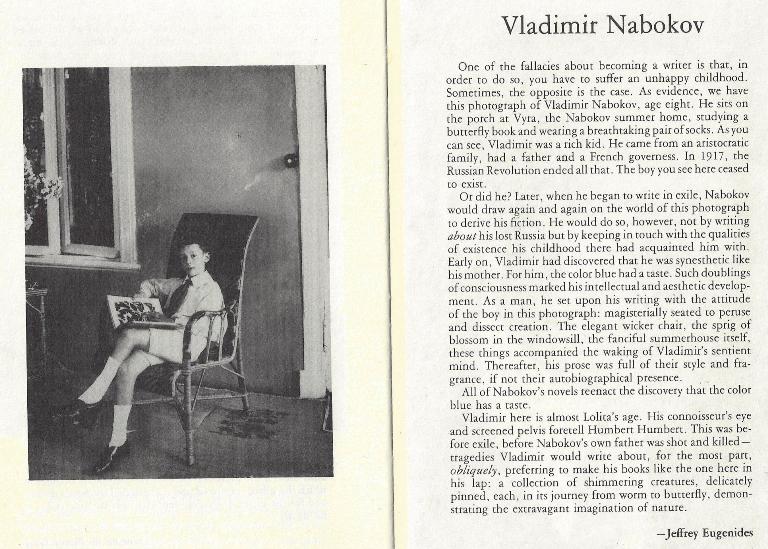

Morrow  Vladimir Nabokov One of the

fallacies about becoming a writer is that, in order to do so, you have

to

suffer an unhappy childhood. Sometimes, the opposite is the case. As

evidence,

we have this photograph of Vladimir Nabokov, age eight. He sits on the

porch at

Vyra, the Nabokov summer home, studying a butterfly book and wearing a

breathtaking pair of socks. As you can see, Vladimir was a rich kid. He

came

from an aristocratic family, had a father and a French governess. In

1917, the Russian

Revolution ended all that. The boy you see here ceased to exist. Or did he?

Later, when he began to write in exile, Nabokov would draw again and

again on

the world of this photograph to derive his fiction. He would do so,

however,

not by writing about his lost Russia

but by keeping in touch with the qualities of existence his childhood

there had

acquainted him with. Early on, Vladimir had discovered that he was

synesthetic

like his mother. For him, the color blue had a taste. Such doublings of

consciousness marked his intellectual and aesthetic development. As a

man, he

set upon his writing with the attitude of the boy in this photograph:

magisterially seated to peruse and dissect creation. The elegant wicker

chair,

the sprig of blossom in the windowsill, the fanciful summerhouse

itself, these

things accompanied the waking of Vladimir's sentient mind. Thereafter,

his

prose was full of their style and fragrance, if not their

autobiographical

presence. All of

Nabokov's novels reenact the discovery that the color blue has a taste.

Vladimir

here is almost Lolita's age. His connoisseur's

eye and screened pelvis foretell Humbert Humbert. This was before

exile, before

Nabokov's own father was shot and killed- tragedies Vladimir would

write about,

for the most part, obliquely, preferring to make his books like the one

here in

his lap: a collection of shimmering creatures, delicately pinned, each,

in its

journey from worm to butterfly, demonstrating the extravagant

imagination of

nature. -Jeffrey Eugenides Một trong những quái đản

về chuyện trở thành nhà văn, là phải

có 1 tuổi

thơ khốn nạn.  Russian

Portraits

The

portraits that follow are from a large number of photographs recently

recovered

from sealed archives in Moscow, some-rumor has it-from a cache in the

bottom of

an elevator shaft. Five of those that follow, Akhmatova, Chekhov (with

dog), Nabokov,

Pasternak (with book), and Tolstoy (on horseback) are from a volume

entitled The Russian Century,

published early last year by Random House. Seven

photographs from that research, which were not incorporated in The

Russian

Century, are published here for the first time: Bulgakov, Bunin,

Eisenstein (in

a group with Pasternak and Mayakovski), Gorki, Mayakovski, Nabokov

(with mother

and sister), Tolstoy (with Chekhov), and Yesenin. The photographs of

Andreyev,

Babel, and Kharms were supplied by the writers who did the texts on

them. The photograph

of Dostoyevsky is from the Bettmann archives. Writers who were thought

to have

an especial affinity with particular Russian authors were asked to

provide the

accompanying texts. We are

immensely in their debt for their cooperation. The Paris

Review  Daniil

Kharms Among the

millions killed by Stalin was one of the funniest and most original

writers of

the century, Daniil Kharms. After his death in prison in 1942 at the

age of

thirty-seven, his name and his work almost disappeared, kept alive in

typescript texts circulated among small groups of people in the then

Soviet Union.

Practically no English-speaking readers knew of him. I didn't,

until I went to Russia and came back and read books about it and tried

to learn

the language. My teacher, a young woman who had been in the U.S. only a

few

months, asked me to translate a short piece by Daniil Kharms as a

homework

assignment. The piece, "Anecdotes from the Life of Pushkin,"

appears in CTAPYXA (Old Woman), a

short collection of Kharms's work published in Moscow in 1991. Due to

my

newness to the language and the two dictionaries and grammar text I had

to use,

my first reading of Kharms proceeded in extreme slow motion. As I

wondered over

the meaning of each word, each sentence; as the meaning gradually

emerged, my

delight grew. Every sentence was, funnier than I could have guessed. A

paragraph began: "Pushkin loved to throw rocks." Openings like that

made me breathless to find out what would come next. The well-known

difficulty

of taking humor from one language into another has a lesser-known

correlate:

when, as sometimes happens, the translation succeeds, the joke can seem

even

funnier than it was to begin with. As I translated, I thought Kharms

the

funniest writer I had ever

read. -Ian Frazier Trong

số hàng triệu con người bị Stalin sát hại, có một nhà văn tức cười

nhất, uyên

nguyên nhất, của thế kỷ: Daniil Kharms. Sau khi ông chết ở trong tù,

vào năm

1942, khi 37 tuổi, tên và tác phẩm của ông hầu như biến mất, và chỉ còn

sống dưới

dạng chép tay, lưu truyền giữa những nhóm nhỏ, ở một nơi có tên là Liên

Bang Xô

Viết.  Chân

Dung Nga |