|

Về Pạt,

thật nhã

Độc giả Việt

Nam đã sớm đọc được từ năm 1974, với bản dịch của Nguyễn Hữu Hiệu, nhan

đề

"Vĩnh biệt tình em", do Tổ hợp Gió xuất bản tại Saigon. Và sau đó là

bản dịch của Lê Khánh Trường, in trong "Boris Pasternak, Con người và

tác

phẩm", Nxb Tp Hồ Chí Minh, 1988. Bản tiếng Việt

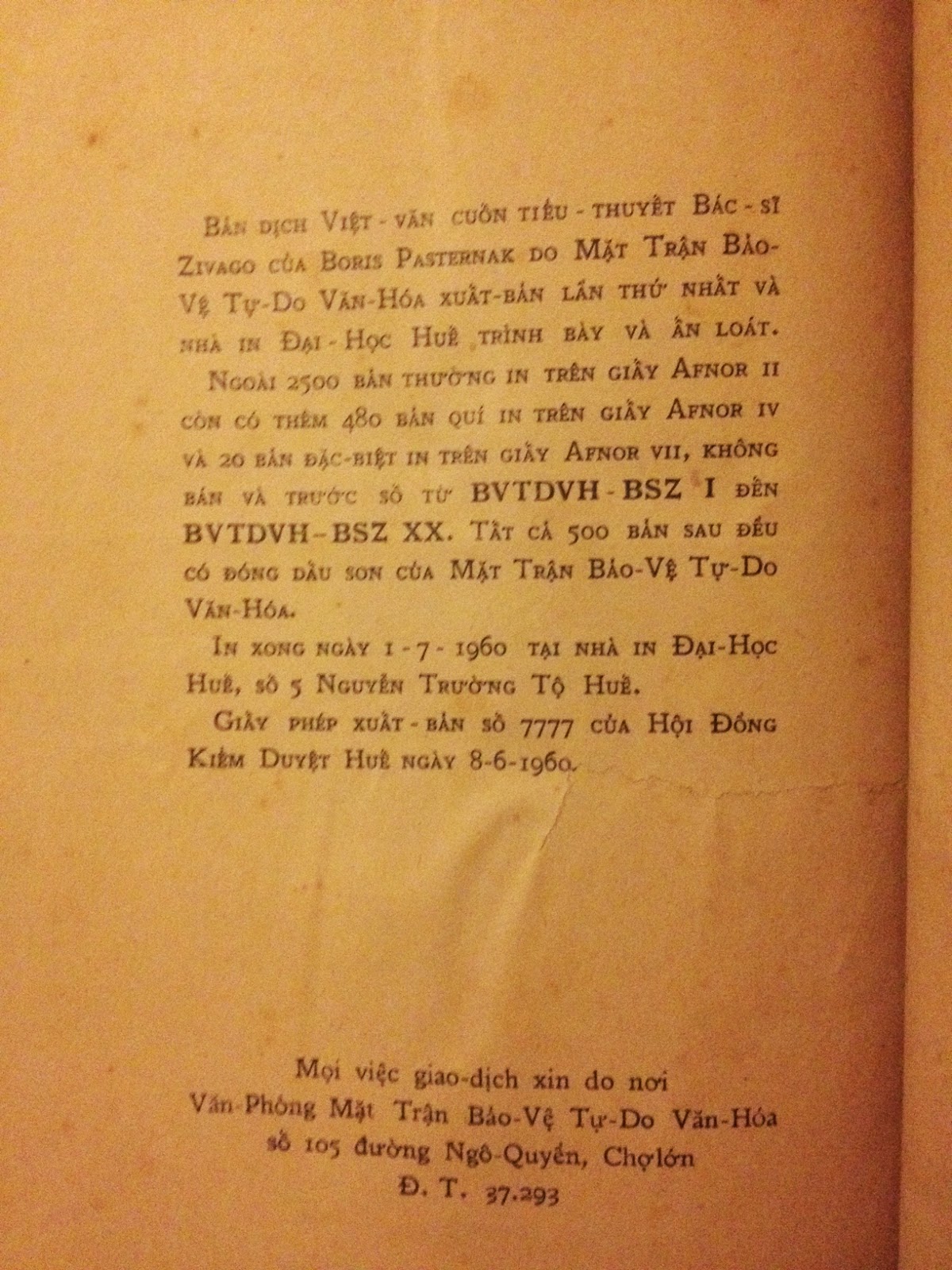

đầu tiên, là của Mặt Trận Bảo Vệ Văn Hóa. Đây là cuốn sách vỡ lòng của

Gấu, thời

gian học Đệ Nhất Chu Văn An, quen bạn Chất, em trai TTT, và cùng đọc

nó, với bà

cụ thân sinh của nhà thơ. Trên TV cũng đã từng lai rai nhiều lần về

chuyện này

rồi. Nhưng cái giải

thưởng Nobel quả thực là làm cho Pạt rất ư là bực, Khi nghe tin được

giải, không

phải như là nhà thơ, mà là tác giả “Zhivago”, ông gần như phát khùng,

như

Milosz viết: Về Pạt, thật nhã Với những ai quen thuộc

với thơ của

ông, trước khi ông nổi tiếng thế giới, thì giải Nobel ban cho ông vào

năm 1958

quả là có 1 cái gì tiếu lâm ở trong đó. Một nhà thơ mà thế giá ở Nga,

người

ngang hàng với ông chỉ có 1, là nữ thần thi ca Akhmatova; một đại gia

về dịch

thuật, nếu không muốn nói, "thiên tài dịch dọt", [hai từ đều thuổng

cả!],

thì mới dám đụng vô Shakespeare, vậy mà phải viết một cuốn tiểu

thuyết to

tổ bố, và cuốn tiểu thuyết to tổ bố này phải gây chấn động giang hồ, cả

Ðông lẫn

Tây, cả Tà lẫn Chính, và trở thành một best-seller, [có lẽ phải thêm

vô, phải

có bàn tay lông lá của Xịa nữa] tới lúc đó, những thi sĩ của những xứ

sở

Slavic, mà ông ta nhân danh, mới được Uỷ Ban Nobel ở Stockholm, thương

tình để

mắt tới. Sau khi được Nobel, Pạt

mới hiểu ra

được, và thấy mình, ở trong một đại ác mộng! Một đại ác mộng về sự hồ

nghi,

chính tài năng của mình! Trong khi ông khăng khăng khẳng định với chính

mình,

tác phẩm của ta là một toàn thể, thì cái toàn thể bị bẻ gẫy vì những

hoàn cảnh.

Czeslaw

Milosz Lara mới là nhân vật chính của cuốn tiểu thuyết. Cú soi sáng này soi sáng cùng 1 lúc, đa số nhân vật. Kiệt chẳng thế ư, so với vợ là Thùy, hay so với Hiền, đảo xa Nhà văn và tên bồi Gấu nhớ là có đọc đâu đó, người tình Lara của Pạt là nhân viên KGB, nhưng đọc bài viết trên TLS, không phải. Số phận Lara thật là thê lương, sau khi Pạt mất. Và nhân vật nữ này quả đúng là tượng trưng cho nước Nga nát tan vì Cách Mạng: Liệu chúng ta có thể coi cái cú em Phương bị 1 bầy Bộ Đội Cụ Hồ bề hội đồng ở ga Thanh Hoá, như là 1 lời tiên tri - trù ẻo đúng hơn - và sau đó, trong "Cánh Đồng Bất Tận", nó biến thành… hiện thực? Awarded the

Nobel Prize for Literature in 1958, he was compelled by the Kremlin to

renounce

it. The Komsomol leader, Vladimir Semichastnyi, contrasted him

unfavorably with

a pig which would never foul its own sty. Pasternak, ailing in health

for

years, speculated that the KGB might try to poison him. But he stuck to

his

guns; and although he gave way to Khrushchev on secondary matters, he

took

satisfaction in the lasting damage he had done to the Soviet order.

What he

could not do was protect Olga Ivinskaya from persecution. When he died

in 1960,

her vulnerability was absolute and she was arrested. Even if she had

not been

involved in the practical arrangements for publication abroad, the KGB

would

probably still have gone after her. Indeed, Pasternak had intimated

that she

was the model for the novel's heroine, Lara. Ở Miền Nam,

một nhân vật nữ như Lara, thấp thoáng trong Hà, trong “Sau Cơn Mưa” của

Lý

Hoàng Phong. Ngay từ bài điểm sách đầu tay trên nhật báo “Dân Chủ”, Gấu

đã đưa

cái nhìn này, khi coi “Sau Cơn Mưa” là bản phác, esquisse, cho một cuốn

tiểu

thuyết sẽ có, giống như “Bác Sĩ Zhi Và Gồ” của Pạt. Calvino coi “Bác Sĩ Zhi Và

Gồ” là 1 Odyssey

của thời đại chúng ta:

… The exceptions are the chapters evoking Zhivago's final wanderings through Russia, the horrific march amongst the rats: all the journeys in Pasternak are wonderful. Zhivago's story is exemplary as an Odyssey of our time, with his uncertain return to Penelope obstructed by rational Cyclops and rather unassuming Circes and Nausicaas. Trong ba người đàn ông vây quanh Lara, cả hai đấng Zhivago, và Người Thép Strelnikov, đều là những kẻ thất bại, không xứng với Em, như Calvino nhận định. Xứng với em theo ông, là cái tên khốn nạn, bồ của bà mẹ của em: During the civil war in the Urals, Pasternak shows us both men as though they were already destined for defeat: Antipov-Strelnikov, the Red partisan commandant, terror of the Whites, has not joined the Party and knows that as soon as the fighting is over he will be outlawed and eliminated; and Doctor Zhivago, the reluctant intellectual, who does not want to or is not able to be part of the new ruling class, knows he will not be spared by the relentless revolutionary machine. When Antipov and Zhivago face each other, from the first encounter on the armed train to the last one, when they are both being hunted in the villa at Varykino, the novel reaches its peak of poignancy.  Blog NL (thông tin bổ sung: mới được cho biết ở mấy trang bị thiếu của bản dịch Zivago có dòng chữ: "Văn Tự và Mậu Hải dịch từ nguyên bản tiếng Ý) D.M.Thomas cho biết, Hamlet, ngay từ thoạt kỳ thuỷ của thời đại Stalin, đã bị cấm. Tuy không chính thức, nhưng đám cận thần đều biết, Stalin không muốn Hamlet được trình diễn. Trong một lần tập dượt tại Moscow Art, Stalin hỏi, có cần thiết không, thế là dẹp. Vsevolod Meyerhold, đạo diễn, người ra lệnh Pasternak dịch Hamlet, đành quăng bản dịch vô thùng rác, nhưng ông tin rằng, nếu bất thình lình, tất cả những kịch cọt đã từng được viết ra, biến mất, và may mắn sao, Hamlet còn, thì tất cả những nhà hát trên thế gian này đều được cứu thoát. Chỉ cần diễn hoài hoài kịch đó, là thiên hạ ùn ùn kép tới đầy rạp. Tuy nhiên, cả đời ông, chẳng có được cơ may dựng Hamlet. Nguyễn Huy Thiệp phải đợi 30 năm sau khi cuộc chiến chấm dứt, phải đợi chính đứa thân yêu của ông ngập vào ma tuý, mới nhìn ra vóc dáng ông hoàng Đan Mạch, và sứ mệnh bi thảm của hắn: Giết bố!Ui choa, chẳng lẽ cái cảnh biểu tình, là để… giết ông bố Bắc Kít? Amen! Về Pạt, thật

nhã Với những ai

quen thuộc với thơ của ông, trước khi ông nổi tiếng thế giới, thì giải

Nobel ban

cho ông vào năm 1958 quả là có 1 cái gì tiếu lâm ở trong đó. Một nhà

thơ mà thế

giá ở Nga, người ngang hàng với ông chỉ có 1, là nữ thần thi ca

Akhmatova; một đại gia về dịch

thuật, nếu không muốn nói, "thiên tài dịch dọt", [hai từ đều thuổng

cả!], thì mới dám đụng

vô Shakespeare, vậy mà phải

viết một

cuốn tiểu thuyết to tổ bố, và cuốn tiểu thuyết to tổ bố này phải gây

chấn động

giang hồ, cả Ðông lẫn Tây, cả Tà lẫn Chính, và trở thành một

best-seller,

[có lẽ phải

thêm vô, phải có bàn tay lông lá của Xịa nữa] tới lúc

đó, những thi sĩ của những xứ sở Slavic, mà ông ta nhân danh, mới được

Uỷ Ban Nobel ở Stockholm, thương tình để mắt tới. Sau khi được

Nobel, Pạt mới hiểu ra được, và thấy mình, ở trong một đại ác mộng! Một

đại ác mộng

về sự hồ nghi, chính tài năng của mình! Trong khi ông khăng khăng khẳng

định với

chính mình, tác phẩm của ta là một toàn thể, thì cái toàn thể bị bẻ gẫy

vì những

hoàn cảnh. Tôi không kiếm thấy trong tác

phẩm của Pasternak tí mùi vị của sự

chống đối triết học của ông, với lý thuyết của nhà nước, ngoại trừ cái

sự ngần

ngại khi phải đối đầu với những trừu

tượng

– và như thế, thuật ngữ “trừu tượng” và “giả trá”, với ông, là đồng

nghĩa – và đây

là chứng cớ của sự chống trả của ông. Cuộc sống của công dân Xô Viết là

cuộc sống

của ông, và trong những bài thơ ái quốc, ông không chơi trò chơi chân

thực. Ông

chẳng nổi loạn gì hơn bất cứ 1 con người bình thường Nga Xô. Czeslaw Milosz ZHIVAGO'S

POEMS

HAMLET Bản tiếng

Anh The noise is

stilled. I come out on the stage. The darkness

of night is aimed at me I love your

stubborn purpose, Yet the

order of the acts is planned Bản tiếng Tây Tout se

tait. Je suis monté sur scène, Et je suis

la cible des ténèbres Ton dessein

têtu, pourtant je l'aime, Rien ne peut changer le dénouement. Je suis seul. Les pharisiens sont maîtres. Vivre, ce n'est pas franchir un champ. Bản

tiếng Mít Tiếng ồn tắt ngấm. Tôi bước lên

sàn diễn Tôi trở thành cái đích của đêm

đen Con yêu cái ý định bướng bỉnh

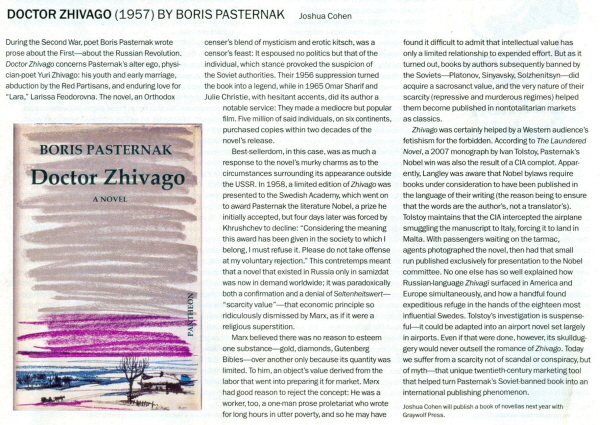

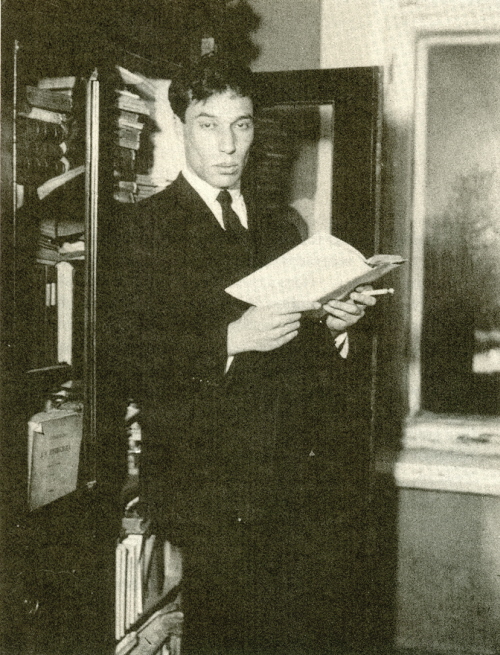

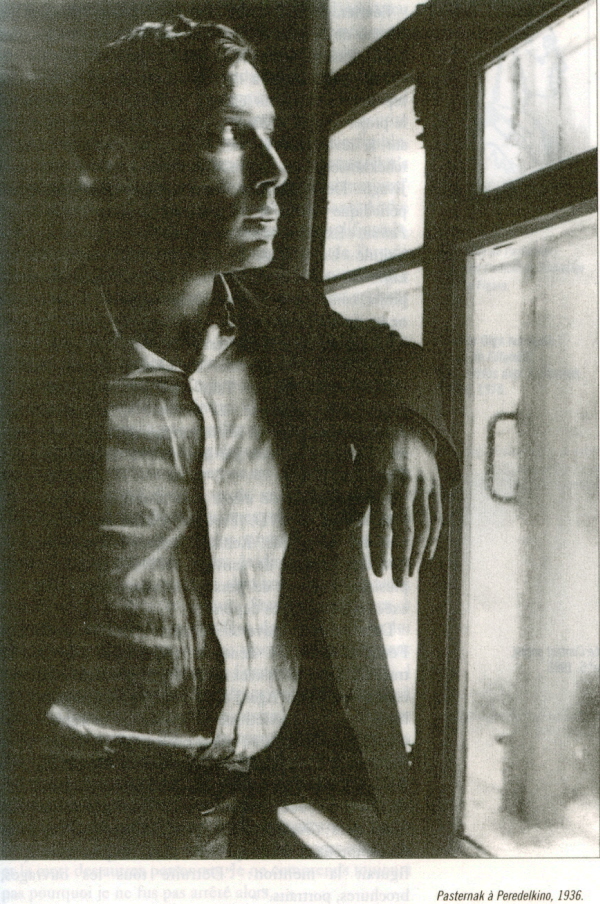

của cha. Nhưng, lệnh lạc đã được phát ra, Tục ngữ Nga  Pasternak à Peredelkino en 1946   Dr Zhivago, Bác Sĩ Zhivago, tình cờ thấy được nhắc

tới, trên hai

tờ, một Bookforum, Summer, 2011, số đặc

biệt về best-sellers, www.bookforum.com Chắc là do ấn

bản tiếng Anh mới nhất mới ra lò. Bài tên tờ Diễn đàn Sách xì ra

chuyện, Xịa,

không phải mafia Do Thái, ban Nobel cho Pasternak.

DOCTOR

ZHIVAGO (1957) BY BORIS

PASTERNAK Joshua Cohen During the

Second War, poet Boris Pasternak wrote prose about the First-about the

Russian

Revolution. Doctor Zhivago

concerns Pasternak's alter ego, physician-poet Yuri

Zhivago: his youth and early marriage, abduction by the Red Partisans,

and

enduring love for "Lara," Larissa Feodorovna. The novel, an Orthodox

censer's

blend of mysticism and erotic kitsch, was a censor's feast: It espoused

no

politics but that of the individual, which stance provoked the

suspicion of the

Soviet authorities. Their 1956 suppression turned the book into a

legend, while

in 1965 Omar Sharif and Julie Christie, with hesitant accents, did its

author a

notable service: They made a mediocre but popular film. Five million of

said

individuals, on six continents, purchased copies within two decades of

the

novel's release. Joshua Cohen

will publish a book of novellas next year with Graywolf Press. BOOKFORUM. SUMMER 2011 Về Pạt, thật

nhã Với những ai

quen thuộc với thơ của ông, trước khi ông nổi tiếng thế giới, thì giải

Nobel ban

cho ông vào năm 1958 quả là có 1 cái gì tiếu lâm ở trong đó. Một nhà

thơ mà thế

giá ở Nga, người ngang hàng với ông chỉ có 1, là nữ thần thi ca

Akhmatova; một đại gia về dịch

thuật, nếu không muốn nói, "thiên tài dịch dọt", [hai từ đều thuổng

cả!], thì mới dám đụng

vô Shakespeare, vậy mà phải

viết một

cuốn tiểu thuyết to tổ bố, và cuốn tiểu thuyết to tổ bố này phải gây

chấn động

giang hồ, cả Ðông lẫn Tây, cả Tà lẫn Chính, và trở thành một

best-seller,

[có lẽ phải

thêm vô, phải có bàn tay lông lá của Xịa nữa] tới lúc

đó, những thi sĩ của những xứ sở Slavic, mà ông ta nhân danh, mới được

Uỷ Ban Nobel ở Stockholm, thương tình để mắt tới. Sau khi được

Nobel, Pạt mới hiểu ra được, và thấy mình, ở trong một đại ác mộng! Một

đại ác mộng

về sự hồ nghi, chính tài năng của mình! Trong khi ông khăng khăng khẳng

định với

chính mình, tác phẩm của ta là một toàn thể, thì cái toàn thể bị bẻ gẫy

vì những

hoàn cảnh. Milosz TO THE

MEMORY OF A POET Like a bird,

echo will answer me. 1. That

singular voice has stopped: silence is complete, 2. Like the

daughter of Oedipus the blind, Akhmatova Boris

Pasternak: 1890-1960, renowned Russian poet and novelist.

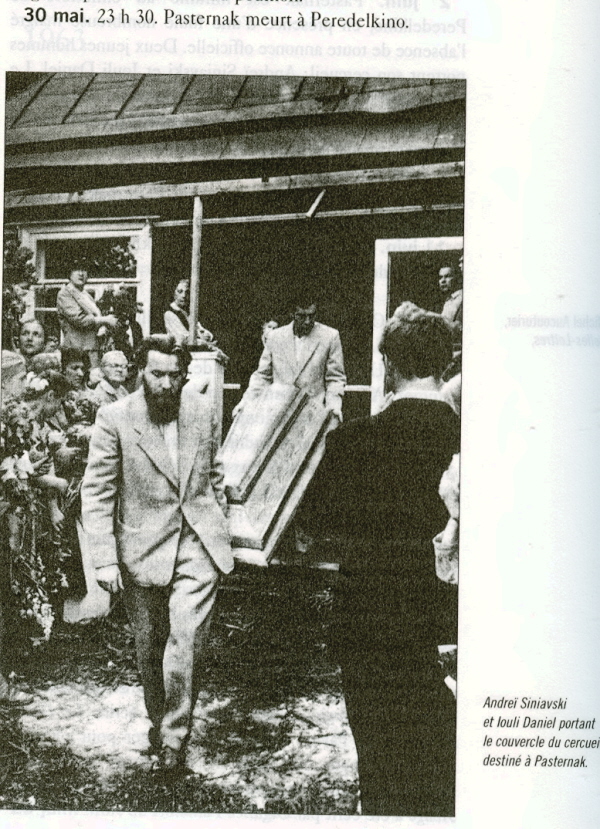

1 er juin.

[1960]. Un discret entrefilet publié par le Fonds littéraire,

l'organisation de secours

mutuel des écrivains, annonce la mort de Pasternak dans Literatoum

i Jizn et Literatournaia

Gazeta, sans préciser l'heure, le jour et le lieu des obsèques.

Mais dans

les wagons de banlieue, à proximité des guichets de gares, apparaissent

des

affichettes les annonçant. Oedipe

aveuglé guidé par sa fille, Traduction

Michel Aucouturier. Revue des Belles-Lettres, mars 1996. I did not find in Pasternak's

work any hint of his philosophical

opposition to the official Soviet doctrine, unless his reluctance to

deal with

abstractions-so that the terms "abstract" and "false" were

for him synonymous-is a proof of his resistance. The life of Soviet

citizens

was his life, and in his patriotic poems he was not paying mere lip

service. He

was no more rebellious than any average Russian. Doctor Zhivago

is a

Christian book, yet there is no trace in it of that polemic with the

anti-Christian concept of man which makes the strength of Dostoevsky.

Pasternak’s Christianity is atheological. It is very difficult to

analyze a Weltanschauung

which pretends not to be a Weltanschauung at all, but simply

"closeness to life," while in fact it blends contradictory ideas

borrowed from extensive readings. Perhaps we should not analyze.

Pasternak was

a man spellbound by reality, which was for him miraculous. He accepted

suffering because the very essence of life is suffering, death, and

rebirth.

And he treated art as a gift of the Holy Spirit. Tôi không kiếm thấy trong tác

phẩm của Pasternak tí mùi vị của sự

chống đối triết học của ông, với lý thuyết của nhà nước, ngoại trừ cái

sự ngần

ngại khi phải đối đầu với những trừu

tượng

– và như thế, thuật ngữ “trừu tượng” và “giả trá”, với ông, là đồng

nghĩa – và đây

là chứng cớ của sự chống trả của ông. Cuộc sống của công dân Xô Viết là

cuộc sống

của ông, và trong những bài thơ ái quốc, ông không chơi trò chơi chân

thực. Ông

chẳng nổi loạn gì hơn bất cứ 1 con người bình thường Nga Xô. Czeslaw Milosz "Tôi

trở nên khiếp đảm bởi nghệ thuật", D. M. Dylan Thomas mở đầu "Hồi tưởng

& Hoang tưởng". Với ông, khả năng thấu thị, nhìn thấy cái chết,

trước

khi nó xẩy ra, ở một cậu bé, chính là "phép lạ" của nghệ thuật, (ở

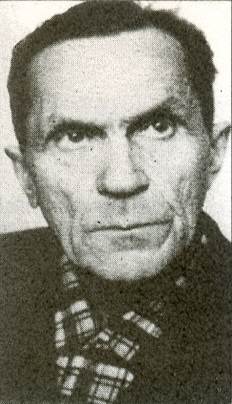

chúng ta). Và ông trở nên khiếp đảm, bởi nó.   Nikolaï

Boukharine en 1921. Conscient dès 1927 que Staline liquiderait la

“Vieille

Garde bolchevique”, “l'enfant chéri du parti " comme il avait été

surnommé, voulut servir Staline jusqu'au bout. Bukharin năm

1921. Biết rất rõ, Stalin sẽ làm thịt đám Cựu Vệ Binh Bôn-xê-vích, "đứa

con cưng

của Đảng", như nick của ông, quyết định hầu hạ Xì tới cùng. Le 13

novembre, dans Troud, N. Boukharine

déclare: «Chez nous aussi, d'autres partis peuvent exister. Mais voici

le

principe fondamental qui nous distingue de l'Occident. La seule

situation

imaginable est la suivante: un parti règne, tous les autres sont en

prison.» Ngày

12.111927, B. tuyên bố trên tờ Troud:

“Ở xứ ta thì cũng vậy, các đảng khác cũng

có thể có. Nhưng đây là nguyên tắc của… Bắc Kít chúng ta, và nó phân

biệt Mít với

Tây Phương. Chỉ có thể có một hoàn cảnh như thế này: Đảng VC Bắc Kít

cầm quyền.

Các đảng khác, vô tù”. Chúng nó làm

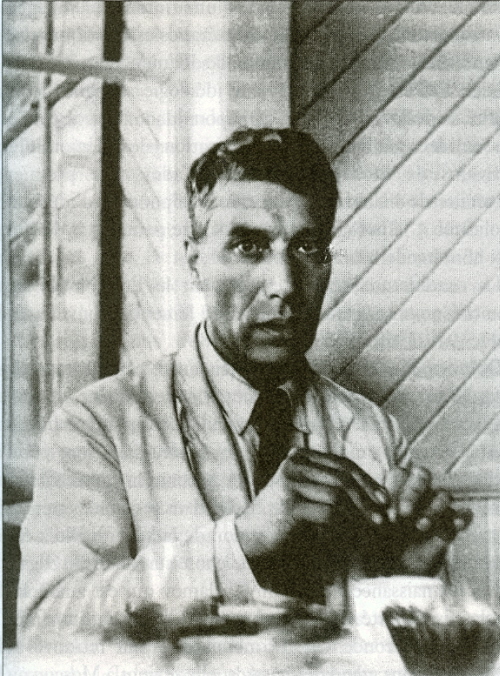

CS. Koestler bắt đầu nhìn ra tình anh em ruột thịt giữa chủ nghĩa CS và chủ nghĩa Phát Xít. Ông bye bye Đảng.    Boris

Pasternak Pasternak's

poems are like the flash of a strobe light-for an instant they reveal a

corner

of the universe not visible to the naked eye. I fell in love with these

poems

as a child. They were magical, fragments of the natural world captured

in words

that I did not always understand. Pasternak was my father's favorite

poet. In

the evenings he often recited his poems aloud, as did Marina

Tsvetayeva, a

friend of the family who often came to our house in those years before

the war. - Olga

Carlisle 16-17 mai

[1933]. Ossip Mandelstam est arrêté dans la nuit pour avoir écrit en

novembre

1933 un

poème sur Staline: «Ses doigts épais sont gras comme des asticots / Et

ses mots

tombent comme des poids de cent kilos. / Il rit dans sa moustache

énorme de

cafard, / Et ses bottes luisent, accrochant le regard. / [ ... ] Et

chaque

exécution est un régal, / Dont se pourlèche l'Ossète au large

poitrail."

Il avait lu son poème à Pasternak dans la rue au début de l'année. Trong The Noise of Time, Tiếng động của thời gian, lời giới thiệu, có một giai thoại thật thú vị liên quan tới Pasternak, vụ bắt nhà thơ Osip Mandelstam và một cú phôn của Bác Xì, từ Điện Cẩm Linh. Liền sau khi

Osip bị bắt, nhà thơ được Stalin đích thân hỏi tội. Đây là một đặc ân

chưa từng

một nhà thơ nào được hưởng, do quyền uy của nhà thơ [perhaps the

profoundest

tribute ever paid by the Soviet regime to the power of Mandelstam’s

pen]. Do

chính Boris Parternak kể lại. -Phải Pạt đó

không? Đây là Xì ta lìn. Chói lọi mới

chẳng trói lại! * Contemporary

trends conceived art as a fountain, though it is a sponge. They decided

it

should spring forth, though it should absorb and become saturated. In

their

estimation it can be decomposed into inventive procedures, though it is

made of

the organs of reception. Art should always be among the spectators and

should

look in a purer, more receptive, truer way than any spectator does; yet

in our

days art got acquainted with powder and the dressing room; it showed

itself

upon the stage as if there were in the world two arts, and one of them,

since

the other was always in reserve, could afford the luxury of self

distortion,

equal to a suicide. It shows itself off, though it should hide itself

up in the

gallery, in anonymity. Đương

thời coi thơ như dòng suối. Không

phải vậy, thơ là miếng bọt biển. Bùi Giáng

(hay Nguyễn Đức Sơn ?): Em chưa vãi

mà hồn anh đã ướt, là cũng ý đó.  Người trong chốn giang hồ, thân không làm chủ. Ôi chao, Gấu

lại nghe ông bạn văn VC than, tại sao anh cứ nhắc mãi đến

Lò

Thiêu? "Tại sao anh

cứ cay đắng mãi như thế?" D. M.

Thomas, trong “Solzhenitsyn, thế kỷ ở trong ta”, chương “Cái

chết

của một thi sĩ”, đã nhận xét, về cuốn Dr. Zhivago: Giả như áp

dụng nhận định trên cho Thơ Ở Đâu Xa, những vần thơ làm ở một

nơi chốn không thể làm thơ, liệu có khiêm cưỡng chăng? Nên nhớ, khi

Pasternak được tin, Nobel trao cho ông vì Dr. Zhivago, ông

rất bực. Ông nghĩ ông phải được Nobel như là nhà thơ. Thông báo giải

thưởng Nobel, tháng 10, 1958, tiếp theo sự ra mắt Dr. Zhivago tại Tây

Phương đã

bùng ra chiến dịch tố cáo, bôi nhọ Pasternak, bắt đầu từ tờ Sự Thật.

Tiếp theo,

Hội Nhà Văn trục xuất ông. Bí thư Thành Đoàn gọi Pasternak là một con

heo ỉa

đái vào cái máng ăn của nó. Pasternak từ chối giải thưởng, nhưng cũng

không yên

thân. Ông gần 70, sức khỏe tồi tệ, chiến dịch làm nhục làm ông hoàn

toàn suy sụp.

Người tình, Olga Ivinskaya, sợ ông bị tim quật chết, và căng hơn, có

thể tự

sát, bèn năn nỉ ông viết thư cho Khrushchev, xin cho ở lại nước Nga, vì

nếu rời

nước Nga, là chết. Ông mất ngày

30 Tháng Năm 1960. Thông báo chính thức, nhỏ nhoi, và, cáo thị độc nhất

về đám

tang, là một bản viết tay, dán ở kế bên quầy bán vé đi Kiev Station, ở

Moscow,

từ đó đi tới Peredelkino, một 'colony' ở ngoại vi thành phố Moscow, là

nơi nhà

văn cư ngụ: Gấu đọc Dr.

Zhivago thời mới lớn, thời gian thường

qua nhà ông anh nhà thơ, đói ăn đói cả đọc. Cùng đọc với bà cụ. Hai bà

cháu

cùng mê đọc. Và cùng mê Dr Zhivago.

Em Lara ở trong truyện đẹp hơn nhiều so với Lara khi được chuyển thể

thành phim,

nhưng bắt

buộc phải như vậy thôi.

Varlam

Chalamov L'ancien Zek

rend visite à Pasternak dès sa sortie du Goulag en 1953. *

Coetzee

nói về Brodsky: Ông chẳng hề loay hoay hì hục làm cho mình được

yêu, thí

dụ, như Pasternak, rất được yêu. Venclova cho rằng, người Nga tìm chẳng

thấy, ở

trong thơ của ông sự "ấm áp", "tha thứ tất cả", "sướt

mướt", "nức nở con tim", hay sự "vui tươi, nhí nhảnh".

Nhà thơ Viktor Krivulin nghi ngờ tính hài hước, rất ư là không giống

Nga, very

un-Russian, vốn trở thành thói quen trong thơ Brodsky. Ông trau giồi

hài hước,

Krivulin nói, để bảo vệ mình, từ những ý nghĩ, tư tưởng, hay hoàn cảnh

mà ông cảm

thấy không thoải mái. "Một sự sợ hãi phải phơi lòng mình ra, hay có

thể,

chỉ là một ước muốn đừng phơi mở...". Ui

chao, liệu có thể bệ cả đoạn trên sang bài tưởng niệm ông anh nhà thơ? Why

not? 5 năm rồi không gặp... 5 năm rồi TTT đã ra đi, nhưng hẳn là ai cũng còn nhớ, khi ông sắp đi, ra lệnh cho vợ con, đừng làm phiền bè bạn, đừng thông báo thông biếc, sống ta đã chẳng làm cho họ vui, cớ sao ta chết, lại làm cho họ buồn? Gấu

phải mãi sau này, mới hiểu ra tại làm sao mà Milosz thèm được cái số

phận bảnh

tỏng của Brodsky: được lọc ra giữa những thi sĩ của thời đại của ông,

của thành

phố của ông, để nhân dân ban cho cái án cải tạo, rồi được Đảng tha cho

về, được

Đảng bắt phải lưu vong, và sau đó, khăn đóng áo dài bước lên Đài cao

nhận

Nobel. Trong khi cái số phần của Milosz, chính là cái mà ông miêu tả

trong bài

viết Rửa, To Wash, 1 thi sĩ bửn của thời

đại của ông. To

Gấu tin là

trong bài thơ tự trào về mình, TTT cho biết, chưa từng bắn một phát

súng, bảo là tự hào, thì thật nhảm (1): thi sĩ cũng muốn có tí bùn dơ ở

trên

người, và sau 30 Tháng Tư, phải cám ơn VC đã cho ông đi tù, cùng bạn

bè,“cùng hội

cùng thuyền”, nhờ cú đi tù mà lại làm được thơ, như những ngày đầu đời,

“nụ hôn

đầu Ga Hàng Cỏ”, bẽn la bẽn lẽn giấu các bạn tù! (1) Một chủ

nhật khác, một cách nào đó, là một bản văn giải thích hành động

không rút súng bắn

VC một lần nào! Nên nhớ, TTT đã từng nhập thân vào bạn của ông, là anh chàng sĩ quan VNCH, Đạo, anh này đã từng nằm suốt đêm ở bên ngoài, chờ cho tên VC nằm vùng, một “serial killer”, chuyên xử tử những tên Ngụy trong vùng, đêm đó lén về nhà, hú hí với vợ con, sáng trở về rừng, mới ra lệnh cho lính dưới quyền nổ súng! TTT có mấy cuốn tiểu

thuyết viết bỏ dở, chưa kể Ung Thư,

hoàn tất nhưng

không cho xb. Trong mấy cuốn đó, cuốn nào cũng thật là tuyệt, ở những

đoạn mở. Uổng

thật! Giấu mặt, viết về 1 em mới nhơn

nhớn, khung cảnh Đà Lạt. Một cú tự thuật, TTT vô

Quang Trung, giữa đám con nít mới lớn,

chúng gọi

ông là Cụ, hay Bố gì đó. Nhân nói chuyện... Bố: Cả trại tù Đỗ Hòa, đám học viên, không chỉ Đội Ba, mà Gấu là Y Tế Đội, đều gọi Gấu là Bố! Bà Cụ Gấu tự

hào lắm, vì “chi tiết là Thượng Đế” thần sầu này!

ON PASTERNAK

SOBERLY FOR THOSE

WHO WERE FAMILIAR with the poetry of Boris Pasternak long before he

acquired

international fame, the Nobel Prize given to him in 1958 had something

ironic

in it. A poet whose equal in Russia was only Akhmatova, and a congenial

translator of Shakespeare, had to write a big novel and that novel had

to

become a sensation and a best seller before poets of the Slavic

countries were

honored for the first time in his person by the jury of Stockholm. Had

the

prize been awarded to Pasternak a few years earlier, no misgivings

would have

been possible. As it was, the honor had a bitter taste and could hardly

be

considered as proof of genuine interest in Eastern European literatures

on the

part of the Western reading public--this quite apart from the good

intentions

of the Swedish academy. THE IMAGE OF

THE POET Half a

century separates us from the Russian Revolution. When we consider that

the

Revolution was expected to bring about the end of the alienation of the

writer

and of the artist, and consequently to inaugurate new poetry of a kind

never

known before, the place Pasternak occupies today in Russian poetry is

astounding.

After all, his formative years preceded World War I and his craft

retained some

habits of that era. Like many of his contemporaries in various

countries, he

drew upon the heritage of French poetes

maudits. In every avant-garde movement, the native traditions

expressed

through the exploration of linguistic possibilities are perhaps more

important

than any foreign influences. I am not concerned, however, with literary

genealogy but with an image which determines the poet's tactics-an

image of

himself and of his role. A peculiar image was created by French poets

of the

nineteenth century, not without help from the minor German Romantics

and Edgar

Allan Poe; this image soon became common property of the international

avant-garde. The poet saw himself as a man estranged from a society

serving

false values, an inhabitant of la cité

infernale, or, if you prefer, of the wasteland and passionately

opposed to

it. He was the only man in quest of true values, aware of surrounding

falsity,

and had to suffer because of his awareness. Whether he chose rebellion

or contemplative

art for art's sake, his revolutionary technique of writing served a

double

purpose: to destroy the automatism of opinions and beliefs transmitted

through

a frozen, inherited style and to mark his distance from the idiom of

those who

lived false lives. Speculative thought, monopolized by optimistic

philistines,

was proclaimed taboo: the poet moved in another realm, nearer to the

heart of

things. Theories of two languages were elaborated: le

langage lyrique was presented as autonomous, not translatable into

any logical terms proper to le langage

scientifique. Yet the poet had to pay the price: there are limits

beyond

which he could not go and maintain communication with his readers. Few

are

connoisseurs. Sophistication, or as Tolstoy called it utonchenie,

is self-perpetuating, like drug addiction. Contemporary

trends conceived art as a fountain, though it is a sponge. They decided

it

should spring forth, though it should absorb and become saturated. In

their

estimation it can be decomposed into inventive procedures, though it is

made of

the organs of reception. Art should always be among the spectators and

should

look in a purer, more receptive, truer way than any spectator does; yet

in our

days art got acquainted with powder and the dressing room; it showed

itself

upon the stage as if there were in the world two arts, and one of them,

since

the other was always in reserve, could afford the luxury of self

distortion,

equal to a suicide. It shows itself off, though it should hide itself

up in the

gallery, in anonymity. Did

Pasternak when writing these words think of himself in contrast with

Vladimir

Mayakovsky? Perhaps. Mayakovsky wanted to smash to pieces the image of

the poet

as a man who withdraws. He wanted to be a Walt Whitman-as the Europeans

imagined Walt Whitman. We are not concerned here with his illusions and

his

tragedy. Let us note only that the instinctive sympathy many of us feel

when

reading those words of Pasternak can be misleading. We have been

trained to

identify a poet's puurity with his withdrawal up into the gallery seat

of a

theater, where in addition he wears a mask. Already some hundred years

ago

poetry had been assigned a kind of reservation for a perishing tribe;

having

conditioned reflexes we, of course, admire "pure lyricism." Not all

Pasternak's poems are personal notes from his private diary or, to put

it

differently, "Les jardins sous la

pluie" of Claude Debussy. As befitted a poet in the Soviet Union,

in

the twenties he took to vast historical panoramas foreshadowing Doctor Zhivago. He enlivened a textbook

cliche (I do not pretend to judge that cliche, it can be quite close to

reality

and be sublime) with all the treasures of detail registered by the eye

of an adolescent

witness; Pasternak was fifteen when the revolutionary events occurred

that are

described in the long poems "The Year 1905" and "Lieutenant

Schmidt." Compared with his short poems, they seem to me failures; the

technique of patches and glimpses does not fit the subject. There is no

overall

commitment, the intellect is recognized as inferior to the five senses

and is

refused access to the material. As a result, we have the theme and the

embroidery; the theme, however, returns to the quality of a cliche. Thus I tend

to accuse Pasternak, as I accused his contemporaries in Poland, of a

programmatic helplessness in the face of the world, of a carefully

cultivated

irrational attitude. Yet it was exactly this attitude that saved

Pasternak's

art and perhaps his life in the sad Stalinist era. Pasternak's more

intellectually inclined colleagues answered argument by argument, and

in consequence

they were either liquidated or they accepted the supreme wisdom of the

official

doctrine. Pasternak eluded all categories; the "meaning" of his poems

was that of lizards or butterflies, and who could pin down such

phenomena using

Hegelian terms? He did not pluck fruits from the tree of reason, the

tree of

life was enough for him. Confronted by argument, he replied with his

sacred

dance. We can agree

that in the given conditions that was the only victory possible. Yet if

we

assume that those periods when poetry is amputated, forbidden thought,

reduced

to imagery and musicality, are not the most healthy, then Pasternak's

was a

Pyrrhic victory. When a poet can preserve his freedom only if he is

deemed a

harmless fool, a yurodivy holy

because bereft of reason, his society is sick. Pasternak noticed that

he had

been maneuvered into Hamlet's position. As a weird being, he was

protected from

the ruler's anger and had to play the card of his weirdness. But what

could he

do with his moral indignation at the sight of the crime perpetrated

upon

millions of people, what could he do with his love for suffering

Russia? That

was the question. His mature

poetry underwent a serious evolution. He was right, I feel, when at the

end of

his life he confessed that he did not like his style prior to 1940: My hearing

was spoiled then by the general freakishness and the breakage of

everything

customary-procedures which ruled then around me. Anything said in a

normal way

shocked me. I used to forget that words can contain something and mean

something

in themselves, apart from the trinkets with which they are adorned ....

I

searched everywhere not for essence but for extraneous pungency. We can read

into that judgment more than a farewell to a technique. He never lost

his

belief in the redeeming power of art understood as a moral discipline,

but his

late poems can be called Tolstoyan in their nakedness. He strives to

give in

them explicitly a certain vision of the human condition. I did not

find in Pasternak's work any hint of his philosophical opposition to

the

official Soviet doctrine, unless his reluctance to deal with

abstractions-so

that the terms "abstract" and "false" were for him

synonymous-is a proof of his resistance. The life of Soviet citizens

was his

life, and in his patriotic poems he was not paying mere lip service. He

was no

more rebellious than any average Russian. Doctor

Zhivago is a Christian book, yet there is no trace in it of that

polemic

with the anti-Christian concept of man which makes the strength of

Dostoevsky. Pasternak’s

Christianity is atheological. It is very difficult to analyze a Weltanschauung which pretends not to be

a Weltanschauung at all, but simply

"closeness to life," while in fact it blends contradictory ideas

borrowed from extensive readings. Perhaps we should not analyze.

Pasternak was

a man spellbound by reality, which was for him miraculous. He accepted

suffering because the very essence of life is suffering, death, and

rebirth.

And he treated art as a gift of the Holy Spirit. We would not

know, however, of his hidden faith without Doctor

Zhivago. His poetry-even if we put aside the question of

censorship-was too

fragile an instrument to express, after all, ideas. To do his Hamlet

deed

Pasternak had to write a big novel. By that deed he created a new myth

of the

writer, and we may conjecture that it will endure in Russian literature

like

other already mythical events: Pushkin's duel, Gogol's struggles with

the

Devil, Tolstoy's escape from Yasnaya Poliana. A NOVEL OF

ADVENTURES, RECOGNITIONS, HORRORS, AND SECRETS The success

of Doctor Zhivago in the West cannot

be explained by the scandal accompanying its publication or by

political

thrills. Western novel readers have been reduced in our times to quite

lean

fare; the novel, beset by its enemy, psychology, has been moving toward

the

programmatic leanness of the antinovel. Doctor

Zhivago satisfied a legitimate yearning for a narrative full of

extraordinary happenings, narrow escapes, crisscrossing plots and,

contrary to

the microscopic analyses of Western novelists, open to huge vistas of

space and

historical time. The novel reader is a glutton, and he knows

immediately

whether a writer is one also. In his desire to embrace the

unexpectedness and

wonderful fluiddity of life, Pasternak showed a gluttony equal to that

of his

nineteenth -century predecessors. Critics have

not been able to agree as to how Doctor

Zhivago should be classified. The most obvious thing was to speak

of a revival

of great Russian prose and to invoke the name of Tolstoy. But then the

improbable encounters and nearly miraculous interventions Pasternak is

so fond

of had to be dismissed as mistakes and offenses against realism. Other

critics,

like Edmund Wilson, treated the novel as a web of symbols, going so far

sometimes

in this direction that Pasternak in his letters had to deny he ever

meant all

that. Still others, such as Professor Gleb Struve, tried to mitigate

this

tendency yet conceded that Doctor Zhivago

was related to Russian Symbolist prose of the beginning of the century.

The

suggestion I am going to make has been advanced by no one, as far as I

know. It is

appropriate, I feel, to start with a simple fact: Pasternak was a

Soviet

writer. One may add, to displease his enemies and some of his friends,

that he

was not an internal émigré but shared the joys and sorrows of the

writers'

community in Moscow. If his community turned against him in a decisive

moment,

it proves only that every literary confraternity is a nest of vipers

and that

servile vipers can be particularly nasty. Unavoidably he followed the

interminable discussions in the literary press and at

meettings-discussions

lasting over the years and arising from the zigzags of the political

line. He

must also have read many theoretical books, and theory of literature in

the

Soviet Union is not an innocent lotus-eaters' pastime but more like

acrobatics

on a tightrope with a precipice below. Since of all the literary genres

fiction

has the widest appeal and can best be used as an ideological weapon,

many of

these studies were dedicated to prose. According to

the official doctrine, in a class society vigorous literature could be

produced

only by a vigorous ascending class. The novel, as a new literary genre,

swept

eighteenth-century England. Thanks to its buoyant realism it was a

weapon of

the ascending bourgeoisie and served to debunk the receding

aristocratic order.

Since the proletariat is a victorious class it should have an

appropriate

literature, namely, a literature as vigorous as the bourgeoisie had in

its

upsurge. This is the era of Socialist Realism, and Soviet writers

should learn

from "healthy" novelists of the past centuries while avoiding

neurotic writings produced in the West by the bourgeoisie in its

decline. This

reasoning, which I oversimplify for the sake of clarity, but not too

much,

explains the enormous prestige of the English eighteenth-century novel

in the

Soviet Union. Pasternak

did not have to share the official opinions as to the economic causes

and

literary effects in order to feel pleasure in reading English

"classics," as they are called in Russia. A professional translator

for many years, mostly from English, he probably had them all in his

own

library in the original. While the idea of his major work was slowly

maturing

in his mind he must often have thought of the disquieting trends in

modern

Western fiction. In the West fiction lived by denying more and more its

nature,

or even by behaving like the magician whose last trick is to unveil how

his

tricks were done. Yet in Russia Socialist Realism was an artistic flop

and of

course nobody heeded the repeated advice to learn from the

"classics": an invitation to joyous movement addressed to people in

straitjackets is nothing more than a crude joke. And what if somebody,

in the

spirit of spite, tried to learn? Doctor Zhivago, a book of hide-and-seek

with fate,

reminds me irresistibly of one English novel: Fielding's Tom

Jones. True, we may have to make some effort to connect the

horses and inns of a countryside England with the railroads and woods

of

Russia, yet we are forced to do so by the travel through enigmas in

both

novels. Were the devices applied mechanically by Pasternak, the

parallel with

Fielding would be of no consequence. But in Doctor

Zhivago they become signs which convey his affirmation of the

universe, of

life, to use his preferred word. They hint at his sly denial of the

trim,

rationalized, ordered reality of the Marxist philosophers and reclaim

another

richer subterranean reality. Moreover, the devices correspond perfectly

to the

experience of Pasternak himself and of all the Russians. Anyone who has

lived

through wars and revolutions knows that in a human anthill on fire the

number

of extraordinary meetings, unbelievable coincidences, multiplies

tremendously

in comparison with periods of peace and everyday routine. One survives

because

one was five minutes late at a given address where everybody got

arrested, or

because one did not catch a train that was soon to be blown to pieces.

Was that

an accident, fate, or providence? If we assume

that Pasternak consciously borrowed his devices from the

eighteenth-century

novel, his supposed sins against realism will not seem so disquieting.

He had

his own views on realism. Also we shall be less tempted to hunt for

symbols in Doctor Zhivago as for raisins in a cake.

Pasternak perceived the very texture of life as symbolic, so its

description

did not call for those protruding and all too obvious allegories.

Situations

and characcters sufficed; to those who do not feel the

eighteenth-century flavor

in the novel, I can point to the interventions of the enigmatic

Yevgraf, the

half-Asiatic natural brother of Yuri Zhivago, who emerges from the

crowd every

time the hero is in extreme danger and, after accomplishing what he has

to,

returns to anonymity. He is a benevolent lord protector of Yuri;

instead of an aristocratic

title, he has connections at the top of the Communist Party. Here again

the

situation is realistic: to secure an ally at the top of the hierarchy

is the

first rule of behavior in such countries as the Soviet Union. THE POET AS

A HERO Yuri Zhivago

is a poet, a successor to the Western European bohemian, torn asunder

by two

contradictory urges: withdrawal into himself, the only receptacle or

creator of

value; movement toward society, which has to be saved. He is also a

successor

to the Russian "superfluous man." As for virtues, he cannot be said

to possess much initiative and manliness. Nevertheless the reader is in

deep

sympathy with Yuri since he, the author affirms, is a bearer of

charisma, a

defender of vegetal "inner freedom." A passive witness of bloodshed,

of lies and debasement, Yuri must do something to deny the utter

insignificance

of the individual. Two ways are offered to him: either the way of

Eastern Christianity

or the way of Hamlet. Pity and

respect for the yurodivy-a half-wit

in tatters, a being at the very bottom of the social scale-has ancient

roots in

Russia. The yurodivy, protected by

his madness, spoke truth in the teeth of the powerful and wealthy. He

was

outside society and denounced it in the name of God's ideal order.

Possibly in

many cases his madness was only a mask. In some respects he recalls

Shakespeare's fool; in fact Pushkin merges the two figures in his Boris

Godunov, where the half-wit Nikolka is the only man bold enough to

shout the

ruler's crimes in the streets. Yuri Zhivago

in the years following the civil war makes a plunge to the bottom of

the social

pyramid. He forgets his medical diploma and leads a shady existence as

the

husband of the daughter of his former janitor, doing menial jobs,

provided with

what in the political slang of Eastern Europe are called "madman’s

papers." His refusal to become a member of the "new intelligentsia"

implies that withdrawal from the world is the only way to preserve

integrity in

a city ruled by falsehood. Yet in Yuri Zhivago there is another trait.

He

writes poems on Hamlet and sees himself as Hamlet. Yes, but Hamlet is

basically

a man with a goal, and action is inseparable from understanding the

game. Yuri

has an intuitive grasp of good and evil, but is no more able to

understand what

is going on in Russia than a bee can analyze chemically the glass of a

windowpane against which it is beating. Thus the only act left to Yuri

is a

poetic act, equated with the defense of the language menaced by the

totalitarian double-talk or, in other words, with the defense of

authenticity.

The circle closes; a poet who rushed out of his tower is back in his

tower. Yuri's

difficulty is that of Pasternak and of his Soviet contemporaries.

Pasternak solved

it a little better than his hero by writing not poems but a novel, his

Hamletic

act; the difficulty persists, though, throughout the book. It is

engendered by

the acceptance of a view of history so widespread in the Soviet Union

that it

is a part of the air one breathes. According to this view history

proceeds

along preordained tracks, it moves forward by "jumps," and the

Russian Revolution (together with what followed) was such a jump of

cosmic

dimension. To be for or against an explosion of historical forces is as

ridiculous as to be for or against a tempest or the rotation of the

seasons.

The human will does not count in such a cataclysm, since even the

leaders are

but tools of mighty "processes." As many pages of his work testify,

Pasternak

did not question that view. Did he not say in one of his poems that

everything

by which this century will live is in Moscow? He seemed to be

interpreting

Marxism in a religious way. And is not Marxism a secularized biblical

faith in

the final accomplishment, implying a providential plan? No wonder

Pasternak, as

he says in his letter to Jacqueline de Proyart, liked the writings of

Teilhard

de Chardin so much. The French Jesuit also believed in the

Christological

character of lay history, and curiously combined Christianity with the

Bergson

an "creative evolution" as well as with the Hegelian ascending

movement. Let us note

that Pasternak was probably the first to read Teillhard de Chardin in

Russia.

One may be justly puzzled by the influence of that poet-anthropologist,

growing

in the last decade both in the West and in the countries of the Soviet

bloc.

Perhaps man in our century is longing for solace at any price, even at

the

price of sheer Romanticism in theology. Teilhard de Chardin has predecessors,

to mention only Alexander Blok's "music of history" or some pages of

Berdyaev. The latent "Teilhardism" of Doctor Zhivago

makes it a Soviet novel in the sense that one might

read into it an esoteric interpretation of the Revolution as opposed to

the

exoteric interpretation offered by official pronouncements. The

historical

tragedy is endowed with all the trappings of necessity working toward

the

ultimate good. Perhaps the novel is a tale about the individual versus

Caesar,

but with a difference: the new Caesar's might has its source not only

in his

legions. What could

poor Yuri Zhivago do in the face of a system blessed by history and yet

repugnant to his notions of good and evil? Intellectually, he was

paralyzed. He

could only rely on his subliminal self, descend deeper than

state-monopolized

thought. Being a poet, he clutches at his belief in communion with ever

reborn

life. Life will take care of itself. Persephone always comes back from

the

underground, winter's ice is dissolved, dark eras are necessary as

stages of

preparations, life and history have a hidden Christian meaning. And

suffering

purifies. Pasternak

overcame his isolation by listening to the silent complaint of the

Russian

people; we respond strongly to the atmosphere of hope pervading Doctor Zhivago. Not without some doubts,

however. Life rarely takes care of itself unless human beings decide to

take

care of themselves. Suffering can either purify or corrupt, and too

great a

suffering too often corrupts. Of course hope itself, if it is shared by

all the

nation, may be a powerful factor for change. Yet, when at the end of

the novel,

friends of the long-dead Yuri Zhivago console themselves with timid

expectations,

they are counting upon an indefinite something (death of the tyrant?)

and their

political thinking is not far from the grim Soviet joke about the best

constitution in the world being one that grants to every citizen the

right to a

postmortem rehabilitation. But Pasternak's weaknesses are dialectically bound up with his great discovery. He conceded so much to his adversary, specuu1ative thought, that what remained was to make a jump into a completely different dimension. Doctor Zhivago is not a novel of social criticism, it does not advocate a return to Lenin or to the young Marx. It is profoundly revisionist. Its message summarizes the experience of Pasternak the poet: whoever engages in a polemic with the thought embodied in the state will destroy himself, for he will become a hollow man. It is impossible to talk to the new Caesar, for then you choose the encounter on his ground. What is needed is a new beginning, new in the present conditions but not new in Russia marked as it is by centuries of Christianity. The literature of Socialist Realism should be shelved and forgottten; the new dimension is that of every man's mysterious destiny, of compassion and faith. In this Pasternak revived the best tradition of Russian literature, and he will have successors. He already has one in Solzhenitsyn. The paradox

of Pasternak lies in his narcissistic art leading him beyond the

confines of

his ego. Also in his reed like pliability, so that he often absorbed

les idees recues without examining them

thoroughly as ideas but without being crushed by them either. Probably

no

reader of Russian poets resists a temptation to juxtapose the two

fates:

Pasternak's and Mandelstam's. The survival of the first and the death

in a

concentration camp of the second may be ascribed to various factors, to

good

luck and bad luck. And yet there is something in Mandelstam's poetry,

intellectually structured, that doomed him in advance. From what I have

said

about my generation's quarrel with worshippers of "Life," it should

be obvious that Mandelstam, not Pasternak, is for me the ideal of a

modern

classical poet. But he had too few weaknesses, was crystalline,

resistant, and

therefore fragile. Pasternak-more exuberant, less exacting, uneven-was

called

to write a novel that, in spite and because of its contradictions, is a

great

book.

|