Dịch thuật | Dịch ngắn | Đọc sách | Độc giả sáng tác | Giới thiệu | Góc Sài gòn | Góc Hà nội | Góc Thảo Trường

Thư tín | Phỏng vấn | Phỏng vấn dởm | Phỏng vấn ngắn

Giai thoại | Potin | Linh tinh | Thống kê | Viết ngắn | Tiểu thuyết | Lướt Tin Văn Cũ | Kỷ niệm | Thời Sự Hình | Gọi Người Đã Chết

Ghi chú trong ngày | Thơ Mỗi Ngày | Nhật Ký | Chân Dung | Jennifer Video

|

|

Nhật

Ký Tin Văn

Lao

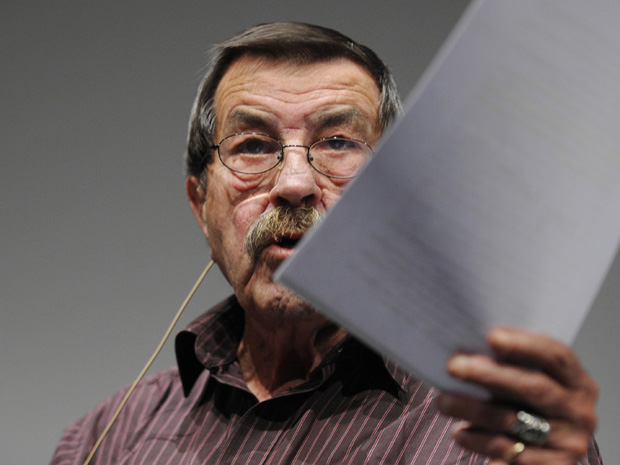

Home, 2014 & 15 Trip[TV last page]  Cu Lùn, Toronto, 11.5.09 GÜNTER GRASS, one of the great German novelists, has died at the age of 87. A man renowned for a willingness to write openly about his country’s 20th-century history, his reputation as a moral authority was dented by the controversies of his later life. In 1959 Mr Grass published his first novel, the one that would go on to define his literary career. Set in his native Danzig, “The Tin Drum” tells the story of 20th-century Germany through the memoirs of its narrator, Oskar Matzerath, a drum-obsessed man-child who has decided never to grow up. The book had a hostile reaction in Germany on its publication, but went on to become hugely successful internationally (and the basis for an Oscar-winning film 20 years later). Other significant works included “Cat and Mouse” and “Dog Years”, which with “The Tin Drum” make up the “Danzig Trilogy”, and “The Flounder”, a sprawling fairy-tale of a novel that charts a much longer span of German history. In 1999 Mr Grass was awarded the Nobel prize for literature, with the committee praising “frolicsome black fables” that “portray the forgotten face of history". Always a polemicist, he expressed doubts about the reunification of Germany in 1990, and in an autobiography published in 2006 he came clean about his membership of the Waffen-SS during the second world war—an admission that many felt should have been made earlier, given Mr Grass’s status as the voice of Germany’s public conscience with respect to its Nazi past. Then in 2012 he was accused of anti-semitism after writing a poem that denounced Israel’s nuclear programme and its aggressive posture towards Iran. A full obituary considering Mr Grass's literary, social and moral impact in greater detail will be available in this week’s Economist. Bài trên tờ Người Kinh Tế, không quên cú thú tội trước bàn thờ của GG, và không quên luôn bài thơ của ông, khi tố cáo Do Thái, về chương trình võ khí nguyên tử của nước này, và thái độ hiếu chiến đối với Iran. Trên TV có nhắc tới vụ này, để coi lại. Günter

Grass’s Poem About Israel Provokes Intense Criticism

"Why

only now, grown old,/And with what ink remains, do I say:/Israel's

atomic power

endangers/an already fragile world peace?" he writes, before answering

his

own question: "Because what must be said/may be too late tomorrow." Tại làm sao

bi giờ, già quá rùi, còn tí mực còn lại, tui lại để cho tay tui dính

mùi "giang

hồ gió tanh mưa máu"? Nghe như giọng

GCC, đếch phải Gunter Grass! Hà, hà! Gunter Grass vừa đi một bài thơ, “Điều phải nói”, tố cáo Israel âm mưu làm cỏ, [wipe out, annihilation] Iran, gây hiểm họa cho hòa bình thế giới. “Tớ quá già rồi, và bằng

những giọt mực chót, cảnh cáo nước Đức của tớ, coi chừng

lại dính vô tội ác [“supplier to a crime”]." (1) Bộ Trưởng ngoại giao Israel, đọc bài thơ, phán, thơ vãi linh hồn [“pathetic”], và cái việc ông ta, Grass, chuyển từ giả tưởng qua khoa học viễn tưởng, coi bộ ngửi không được, poor taste. Günter Grass

pointe tout particulièrement le silence de l'Allemagne, "culpabilisée

par

son passé nazi", qui refuserait de voir le danger constitué par

l'arsenal

nucléaire israélien. Un arsenal "maintenu secret -, et sans contrôle,

puisque aucune vérification n'est permise" et qui "menace la paix

mondiale déjà si fragile", insiste l'écrivain. Il en profite pour

rappeler

que l'Allemagne s'apprête à livrer un sixième sous-marin à Israël.

Berlin et

Tel Aviv ont en effet conclu un contrat en 2005 sur la vente de

sous-marins

Dolphin, qui peuvent être équipées d'armes nucléaires. Enfin, Günter

Grass

réclame la création d'une agence" internationale pour contrôler les

armes

atomiques israéliennes, tout comme l'AIEA le fait pour les activités

nucléaires

iraniennes Grass đặc biệt nhấn mạnh tới sự im lặng của nước Đức, “do tội lỗi bởi quá khứ Nazi”, thành ra vờ, làm ra vẻ không nhìn thấy hiểm họa của võ khí nguyên tử của Israel. Một võ khí nguyên tử “được giữ bí mật, không kiểm cha, kiểm mẹ, vì đếch ai được phép”…

GRASS'S

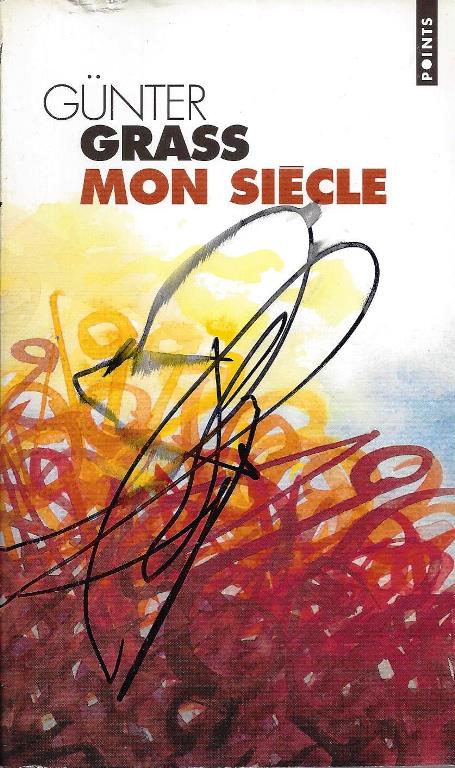

CENTURY From a

writer like Gunter Grass, one expects a masterpiece even on his

deathbed;

though by all indications My Century (Alfaguara)

will be only the second-to-last of his great books. It's a

collection of short stories, one for each year of the century now

behind us, in

which the great German writer examines the frequently tortured fate of

his

country. From the first soccer teams to World War I, from the economic

crisis of

the twenties to the rise of Nazism, from World War II and the

concentration

camps to the German Miracle, from the post-war period to the fall of

the Berlin

Wall, everything has a place in this book, which manages to seem short

though

it's more than four hundred pages long, perhaps because the succession

of

horrors, the succession of disasters, and the human instinct for

survival

despite everything make it feel that way: the century has exhaled. Bolano: Trong Ngoặc. Note: Bài này ngắn, nhưng cực thú. GCC đã tính đi hết cả bài, nhưng lần khân, nay nhân Grass đi xa, bèn gửi với theo. Từ 1 nhà văn

khổng lồ như Grass, người ta hy vọng 1 cuốn khổng lồ, ngay cả khi ông

đang hấp

hối trên giường chờ chết. The Turkish

Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk had warm personal memories: “Grass learned a

lot

from Rabelais and Celine and was influential in development of ‘magic

realism’

and Marquez. He taught us to base the story on the inventiveness of the

writer

no matter how cruel, harsh and political the story is,” he said. Pamuk, nhắc

tới Céline, khi tưởng niệm Grass. Tuy nhiên, qua trả lời phỏng vấn trên

tờ Văn

Học, ML, Grass rất bực khi bị coi là 1 Céline của Đức. Nhân đây, bèn

trích dẫn Kazin, trong bài Intro cho tờ The Paris Review, số có bài

phỏng vấn Céline: Louis-Ferdinand

Celine was an extraordinary and terrifying presence in the

twentieth-century

novel. He was never altogether sane after suffering head wounds in the

First

World War, and by the Second, like other wounded and desperate French

writers

who had come to despair of history, he allied himself with the most

evil forces

in Europe in order to protest the cruelty and injustice that had always

been

under his eye when he practiced medicine in the slums of Paris. Celine

was an

amazingly powerful writer who when interviewed did not make very much

of being

a writer. He thought it enough for a man to tell a story; he must tell

it in order

to be released from life's order; only then can he die in peace. It is

doubtful

that Celine died in peace. But he was so strong and original a

writer-surely he

is the only genius of the French novel since Proust-that when he tells

his

"story" the impact of his life experience becomes one of those blows

which we suffer with gratitude. He describes his childhood in Paris-the

mother,

a lace maker, made the family live on noodles because more pungent

foods left

odors in the lace-he touches on the Fir t World War, on his doctoring.

It is

extraordinary how much, ill these few pages, he says about the human

condition.

Politically, Celine was a maniac. Yet his gift for describing things as

they

are was great, and the compassion he shows in his books is striking. ALFRED KAZIN  Note: Số báo này, mua xon ở Lào. Có bài Intro của Kazin. Tay này tuyệt lắm. Di dân Mẽo gốc Do Thái. Trong tập essay GCC mới mua, dưới đây, có 1 bài rất tuyệt về tay này.  GCC đang

tính tìm hiểu Mít di dân có thể nào thành công không, về cái chuyện

viết lách ở

Mẽo, so với Mẽo gốc Do Thái.

Trên tờ The New Yorker, trong bài viết về cú Mỹ Lai, tác giả có nhắc tới Nguyễn Quí Đức, đấng này về luôn Việt Nam rồi, có giải thích, ở Mẽo không làm sao hoàn tất là 1 con người được, về Việt Nam tìm cái phần thiếu, nhớ đại khái [sẽ check lại sau]. Rồi Thận Nhiên, lưu vong kép, rồi Đinh Linh, rồi Sến ở Đức…

Thơ

Mỗi Ngày

Four Poems

by Charles Simic THE ESCAPEE The name of

a girl I once loved OH, MEMORY You've been

paying visits THE FEAST Dine in

style tonight SCRIBBLED IN

THE DARK Sat up Startled * Hotel of Bad

Dreams. The night

clerk * Body and

soul Playing

their farces * Oh, laggard

snowflake * Softly now,

the fleas are awake. The Paris

Review 209, Summer 2014 [Mới lục ra,

không biết đã dịch chưa!] Rồi! (1) Yes,

defending poetry, high

style, etc., Bảo vệ thơ,

và vân vân. Đúng

rồi, bảo vệ thơ, văn

phong cao, v...v…

Kính

gửi đến ông vài lời, sau

khi làm độc giả thường nhật của tanvien.net hơn một năm nay. Bởi quá

thích, mục

Thơ mỗi ngày, nên hôm nay mới đánh bạo viết mấy dòng gửi ông, để cám ơn

những

gì mà một mình ông làm, kiến tạo và duy trì hào hứng trang web này trong suốt thời gian qua. Kính chúc ông viết hăng

mỗi ngày, và qua việc viết, sẽ đem đến cho đời ông, và độc giả những chất liệu và phương thức sống, đọc

& viết tươi mới mãi. Phúc

đáp: Đa tạ

Mục “Thơ Mỗi Ngày”, do trục trặc

kỹ thuật, một số bài bị ‘delete’. Trong có mấy bài về Pessoa, và mail

của bạn, trên.

Sorry abt that. NQT [GCC post lại mail trên, hy vọng vị độc giả vưỡn đọc TV, và reply, vì GCC không còn địa chỉ mail của vị này] 30.4.2015

EXAMPLE A gale With this example Wislawa Symborska: Here Thí dụ Một trận gió lạnh Với thí dụ này Ui chao, VC quả đã làm

thịt ông bố, nhưng chừa ông con Như có Bác Hồ trong ngày vui đại thắng! Bạn có thể áp dụng bài thơ

trên, cho rất nhiều trường hợp, Nào họ Trịnh hầu đờn Hồ

Tôn Hiến Virtue, after all, is far

from being synonymous with survival;  Bếp Lửa

Ottawa Trong bài viết

về Borges, Hổ trong gương, “Tigers in the mirror”, trên The New Yorker,

sau in

trong “Steiner at The New Yorker”, Steiner có nhắc tới 1 truyện ngắn

của

Borges, mới được dịch qua tiếng Anh, The Intruder. Truyện này hoành

dương,

illustrate, tư tưởng hiện tại của Borges. Tò mò, Gấu

kiếm trong “thư khố” của Gấu, về ông, không có. Lên net, có, nhưng chỉ

cho đọc,

không làm sao chôm: “The Intruder”, câu chuyện hai anh em chia nhau,

một phụ nữ

trẻ. Một trong họ, giết cô gái để cho tình anh em lại được trọn vẹn. Vì

chỉ có

cách đó mà hai em mới cùng san sẻ một cam kết mới: “bổn phận quên

nàng”. Borges coi

nó như là 1 vi-nhét - bức họa nhỏ, dùng để trang trí - cho những những

câu chuyện

đầu tay của Kipling. “Kẻ lén vô nhà, The Intruder”, quả là 1 chuyện

nhỏ, nhẹ,

nhưng không 1 tì vết và cảm động một cách lạ thường. Lần đầu đọc, trên

net, Gấu

mơ hồ nghĩ đến BHD, tượng trưng cho thứ văn học của Gấu, hay rộng ra,

của cả Miền

Nam đúng hơn, được cả hai thằng, anh Bắc Kít và em Nam Kít, cùng mê, và

1 thằng

đã "làm thịt em" để cả hai cùng có bổn phận, quên nàng: Như thể, sau

khi Gấu lang thang xứ người, lưu vong nơi Xứ Lạnh, một bữa trở về Xề

Gòn, và thấy

Những Ngày Ở Sài Gòn, nằm trên bàn! "The

Intruder," a very short story recently translated into English,

illustrates Borges's present ideal. Two brothers share a young woman.

One of

them kills her so that their fraternity may again be whole. They now

share a

new bond: "the obligation to forget her." Borges

himself compares this vignette to Kipling's first tales. "The

Intruder" is a slight thing, but flawless and strangely moving. It is

as

if Borges, after his rare voyage through languages, cultures,

mythologies, had

come home and found the Aleph in the next patio. Steiner cho

rằng cái sự nổi tiếng của Borges làm khổ dúm độc giả ít ỏi, như là 1 sự

mất mát riêng tư. Vào cái tuổi

già chín rục, Borges tếu táo, tôi bắt đầu nghi, rằng thì là bi giờ cả

thế giới

biết tới mình! TTT cũng thế. May sau đó,

nhờ Nguyễn Đình Vượng, đổ mớ sách ra hè đường Xề Gòn, nhờ thế cuốn sách

tái

sinh, từ tro than, từ bụi đường! Gấu là thằng

may nhất, nếu không có cú bán xon của NDT, Gấu không làm sao được đọc

Bếp Lửa! Viết  A brief

survey of the short story: Italo Calvino "My

author is Kafka", Calvino once told an interviewer when asked about his

influences, and his presence is discernible throughout Calvino's work,

from The

Argentine Ant to the 1984 story Implosion. Here Calvino links two of

literature's most introspective characters, the doomed prince Hamlet

(the story

begins: "To explode or to implode – said Qfwfq – that is the

question") and the mole-like creature from Kafka's death-haunted story

The

Burrow, in a beautiful but deeply melancholic rumination on black holes

and the

death of the universe, and an apprehension that obliteration lies at

the heart

of each individual consciousness:

"Don't distract yourselves fantasizing

over the reckless behaviour of hypothetical quasi-stellar objects at

the

uncertain boundaries of the universe: it is here that you must turn

your

attention, to the centre of our galaxy, where all our calculations and

instruments indicate the presence of a body of enormous mass that

nevertheless

remains invisible. Webs of radiation and gas, caught there perhaps

since the

time of the last implosions, show that there in the middle lies one of

these

so-called holes, spent as an old volcano. All that surrounds it, the

wheel of

planetary systems and constellations and the branches of the Milky Way,

everything in our galaxy rests on the hub of this implosion sunk away

into

itself." Không 1 tên Mít nào viết nổi 1 câu thật là bình thường như vậy. Bài viết này, nằm trong loạt bài nghiên cứu về truyện ngắn của tờ Guardian. Bài này cũng thật là tuyệt

Monsters

Together  Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov signing the Nazi–Soviet Pact, with German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop directly behind him, next to Stalin, August 23, 1939 In the vast literature about Stalin and Hitler

during World War II, little is said about their being allies for

twenty-two months. That is more than an odd chapter in the history of

that war, and its meaning deserves more attention than it has received. Ít người còn nhớ Nazi và Liên Xô đã từng là bạn quí! TTT 2006-2015 Nỗi Buồn Hoa

Phượng Nhà thơ TTT

có lần ngồi Quán Chùa, nhân lèm bèm về nhạc sến, đúng hơn, nhạc có lời,

ông

phán, GCC nhớ đại khái, ở trong chúng, có cái gọi là nhịp của thời gian. Hết

năm học, một em, còn nhớ, người Nam, đưa cho GCC 1 cuốn sổ nho nhỏ, GGC

nhớ là,

đẹp lắm, và nói, anh viết vài dòng lưu bút cho em! Cũng chẳng

nhớ 1 tí gì, về nội dung bức thư tình.

|

Cảnh đẹp VN Giới Thiệu Sách, CD Art2all Việt Nam Xưa Talawas Guardian Intel Life Huế Mậu Thân Cali Tháng Tám 2011 30. 4. 2013 Thơ JHV TMT Trang đặc biệt Tưởng nhớ Thảo Trường Tưởng nhớ Nguyễn Tôn Nhan TTT 2011 TTT 2012 7 năm TTT mất Xử VC Hình ảnh chiến tranh Việt Nam của tờ Life Vĩnh Biệt BHD 6 năm BHD ra đi Blog TV  Lô cốt trên đê làng Thanh Trì, Sơn Tây Bếp Lửa

trong văn chương

Báo Văn [Phê Bình] cũ, có bài của GCC Mù Sương Hồi Ký Viết Dưới Hầm Nghĩ về phê bình Mây Bay Đi Nguyễn Du giữa chúng ta "Tạp Ghi" by Tuấn Anh Chữ và Việc TSVC Nhã Tập Truyện Kiều ABC Xuân Vấn Đề Kỷ Dậu Truyện ngắn Võ Phiến Những ngày ở Sài Gòn nhà xb Hoàng Đông Phương Mộ Tuyết [Hồi bắt đầu đi làm] Happy Birthday GCC, 2012 SN 16.8.2013 Cali 3.08 Cali Tháng Tám 2011 Vietnam's Solzhenitsyn NQT vs DPQ @ NMG's Lolita vs BHD |