Nguyễn Quốc Trụ

Sinh 16 tháng Tám,

1937

Kinh

Môn,

Hải Dương

[Bắc

Việt]

Quê

Sơn

Tây

[Bắc Việt]

Vào

Nam

1954

Học

Nguyễn

Trãi

[Hà-nội]

Chu Văn An,

Văn Khoa

[Sài-gòn]

Trước

1975

công

chức

Bưu

Điện [Sài-gòn]

Tái

định

cư năm

1994

Canada

Đã

xuất

bản

Những

ngày

ở Sài-gòn

Tập

Truyện

[1970,

Sài

Gòn,

nhà

xb Đêm

Trắng

Huỳnh

Phan

Anh

chủ

trương]

Lần

cuối,

Sài-gòn

Thơ,

Truyện,

Tạp

luận

[Văn

Mới,

Cali.

1998]

Nơi

Người

Chết

Mỉm Cười

Tạp

Ghi

[Văn

Mới,

1999]

Nơi

dòng

sông

chảy

về phiá

Nam

[Sài

Gòn

Nhỏ,

Cali,

2004]

Viết

chung

với

Thảo Trần

Chân

Dung

Văn Học

[Văn

Mới,

2005]

Trang Tin Văn, front page, khi quá đầy,

được

chuyển

qua Nhật

Ký

Tin Văn,

và

chuyển

về

những

bài

viết

liên

quan.

*

Một

khi

kiếm,

không

thấy trên

Nhật

Ký,

index:

Kiếm

theo

trang

có

đánh

số.

Theo

bài

viết.

Theo

từng

mục,

ở đầu trang

Tin

Văn.

Email

Nhìn

lại

những trang

Tin

Văn

cũ

1

2

3

4

5

Bản quyền Tin Văn

*

Tất

cả bài

vở

trên

Tin Văn,

ngoại

trừ

những

bài

có

tính

giới

thiệu,

chỉ

để sử dụng

cho cá

nhân

[for personal

use], xài

thoải

mái

[free]

Liu

Xiaobo

Elegies

Nobel

văn

chương

2012

Anh

Môn

Kỷ niệm 100 năm sinh của Milosz

IN MEMORIAM

W. G. SEBALD

http://tapchivanhoc.org

|

Waiting For SN

Bác «lãng

mạn» quá, cứ mong chờ có một cú ngoạn

mục của các nhân tài.

O.

Lãng mạn phải là

chúng mày mới đúng. Đau khổ cho nhiều vào,

đọc sách cho nhiều vào, xót thương mình chưa

đủ rồi xót thương người… để mơ mộng: cách mạng. Ôi

chao cách mạng! Cách mạng để làm gì? Những

con ngựa bị hành hạ đau quá thì lồng lên hất

thằng dô kề ngã mà chạy. Chạy đi đâu? Thằng

dô kề nó sẽ túm được, nó đánh đập tàn

nhẫn hơn và lại sỏ cương trèo lên.

Bếp

Lửa [TTT]

Ngày

Lễ Cha

Kenzaburo

Oe: Cha và Con ( Nguyễn Quốc Trụ)

Vài dòng về một người cha ( Phạm Đình

Lân)

Con sẽ

về ( Hoa Cát Phan Văn)

Khi Chúa tạo ra những Ông Bố - Erma

Bombeck ( Đặng Lệ Khánh dịch)

Thư gởi ba - Lisa M. Krieger (Đặng

Lệ Khánh dịch)

Hạt giống (

Hồ Đình Nghiêm)

Thần tượng ( Ca

Dao)

26

Three Letters to His Father

[Thư gửi Bố của Kafka]

Kafka's lengthy letter to his father, composed

in mid-November 1919 in Schelesen (Zelizyj, is now considered

to be one of the most powerful and paradigmatic father-and-son

confrontations. Less well known, however, is the fact that this

letter had a precursor, which Kafka abandoned after just a few

pages. Unlike the finished "Letter to His Father," this earlier

draft is still formally addressed to both of his parents, although

the true addressee is clearly just his father:

Dear Parents, on the evening

when Hugo Kaufmann last visited us, and you Father, Karl, and Hugo

discussed various business and family affairs, I later overheard

you from the bathroom, complaining to Mother about my lack of engagement

in the conversation. It was not the first time that I have heard

you make these sorts of accusations against me, Father, and you have

not always done it through closed doors, you have also said it directly

to my face, and your accusations have not been not limited to my lack

of engagement, Father, as weighty as that is in itself-still, your criticism

that evening, although I could not even hear all of it clearly, made

me even sadder than usual. For a long time I sought some way out, until

finally, as I lay in bed, it occurred to me that I could write you a

letter and explain everything, since you would have time to read at the

spa. This idea gave me such joy that I thought at once of 100 things that

I must write to you, and moreover of a system that would make them completely

persuasive. The next morning, though, while my joy about the idea was still

there, as it still is today, my confidence in my own ability to carry

it out is lacking, although in the end my task comes down to the most basic

things. So I am beginning this letter without self-confidence, and only

in the hope that you, Father, will still love me in spite of it all, and

that you will read the letter better than I write it.

If you think back a bit, Father, I'm sure we agree

that our relationship in the past few years has been almost unbearable

at times. (My relationship to Mother may not be fundamentally

different, but because of her unlimited selflessness, which relieves

me of all my duties to her, I do not see that and barely feel it.)

I am to blame for this unbearable relationship, I alone. In general

I have not concerned myself with your affairs even as much as a casual

acquaintance would have done (to say nothing of a son's duties), and

when I did concern myself with them, it was clear that I was only doing

so under pressure; I have not fulfilled my responsibilities to my Sisters,

and in that respect I have not relieved you of any troubles;

This draft, which cannot be

dated, has a much more defensive tone than the finished letter;

therefore it was certainly written before 1919, possibly years earlier

(Hans-Cerd Koch, the editor of Kafka's letters, considers May 1918

to be the most likely date). Apparently this draft was written before

several family conflicts arose, cases where Kafka considered his father

to be clearly in the wrong- particularly Hermann's alienation from his

daughter Ottla, as well as the conflict surrounding Kafka's recent engagement

to Julie Wohryzek. When Kafka told his parents in September 1919 that he

intended to marry Wohryzek, a woman of modest means, his father berated

and humiliated him. After that altercation, Kafka felt a need to settle

a score, not merely to explain himself.

In addition to this draft and

the famous later letter, Kafka made at least one more attempt

to resolve their differences in writing. In April 1918, as he prepared

to return to his parents' apartment in Prague after spending months

on a farm where his sister Ottla was the caretaker, he sent a letter

in advance to his father. In it, Kafka apparently touched on quite

uncomfortable topics, especially his father's aversion to the country

life that Ottla had chosen-an aversion so intense that the mere mention

his youngest daughter was sometimes enough to make their father fly into

a rage. This letter is no longer extant but evidence of its impact can

be seen in an unpublished letter written to Ottla by her close friend,

their cousin Irma. Irma worked in Kafka's father's fancy goods store, so

she was particularly subject to his moods. On April 25, 1918, five days

before Kafka returned to Prague, Irma complained to Ottla about "the mess

Franz made for me with his letter to your father."

To die for others

is difficult enough.

To live for others is even harder.

G. Steiner: Errata

Nhờ ông bố, Steiner thoát chết ở Lò Thiêu.

Tôi cũng là thứ sống sót, ông nói về mình.

Và, bèn tự an ủi, bằng câu trên

Chết vì người khác, đủ khó

Sống vì họ, khó hơn nhiều!

Thơ Mỗi Ngày

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/06/20/fourteen-by-marie-howe

Poems June 20, 2016 Issue

Fourteen

By Marie Howe

She is still mine—for another year or

so—

but she’s already looking past me

through the funeral-home door

to where the boys have gathered

in their dark suits.

Mười bốn

Em vưỡn là của GCC - một năm nữa, cỡ đó

Nhưng Em đã nhìn quá GCC

Qua cái cửa nhà đòn

Tới cái chỗ đám nhóc trong những

bộ đồ tang tụ tập

Đinh Cường Tribute

Tribute to

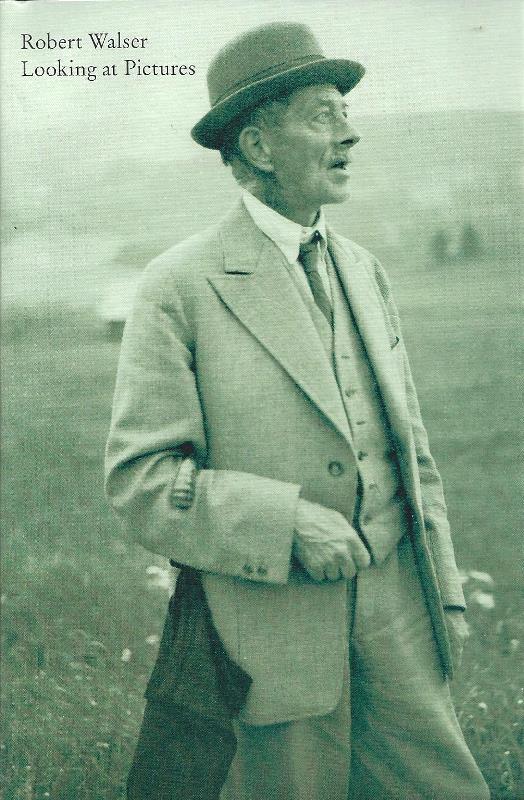

Robert Walser

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2016/06/23/robert-walser-adorable-bookling/

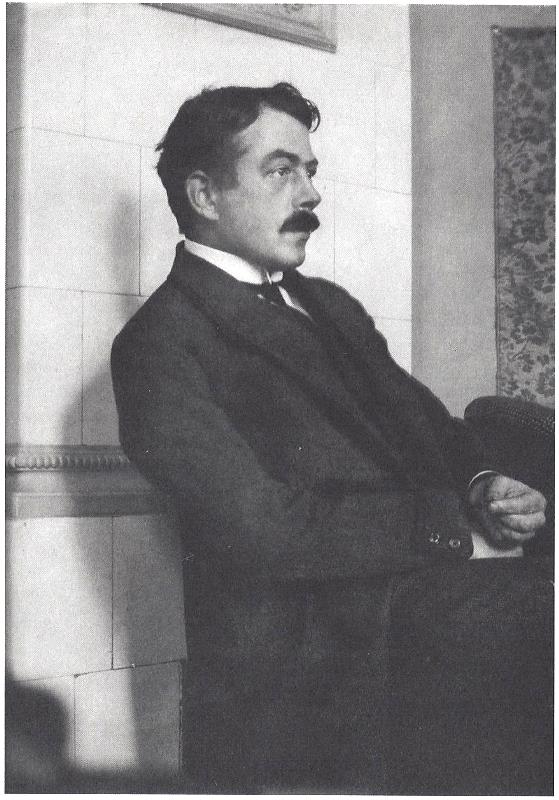

Robert

Walser, Berlin, cc 1907

‘An Adorable Bookling’

Looking at Pictures

by Robert Walser, translated from the German by Susan Bernofsky,

with additional translations by Lydia Davis and Christopher Middleton

Christine Burgin/New Directions, 143 pp., $24.95

Tờ NYRB số mới nhất, 23 June,

2016, đi 1 đường về Walser, điểm cuốn Tin Văn đã/đang giới thiệu,

Looking at Pictues, như 1 tưởng niệm 10 năm TTT

ra đi, và bạn ông, Đinh Cường, mới ra đi.

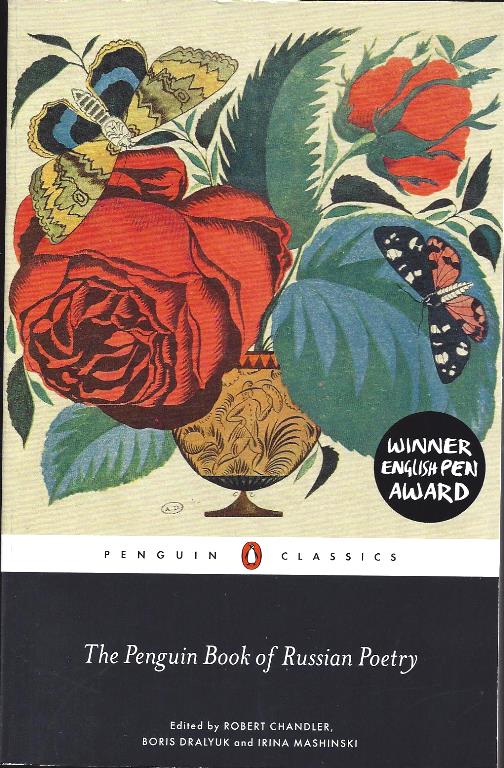

Elena Shvarts (1948-2010)

Born in Leningrad, Elena Andreyevna Shvarts

attended the University of Tartu in Estonia. She published her

first poems in the Tartu University newspaper in I973, but from

then until 1989 - although well known in Russia - she was able

to publish only abroad or in samizdat.

The poet and translator Sasha

Dugdale writes: 'In Shvarts's poetry, the world about her is

transformed into a unique and mystical landscape, half-real, half-Breughelesque

fantasy. St Petersburg's streets and enormous tenement blocks

are peopled by the souls of the dead, the River Neva is an often malign

force, the street where she once lived becomes "my Paradise, my lost

Paradise". Her work is full of religious imagery: angels, demons,

fools-in-Christ, icons and visions of heaven and hell, but the belief

which illuminates the poems is far from orthodox. [ ... ] In her

writing, poetry itself is the sacred act [ ... ] She writes in

one poem, "When an angel carries away my soul/all shrouded in fog,

folded in flames / I have no body, no tears to weep / just a bag

in my heart, full of poems."

A metaphor running though

Shvarts's work is that of bird- song escaping from a cage. The

poem 'Birdsong on the Seabed' ends:

Is it worth singing where no one can hear,

unrolling trills on the bed?

I am waiting

for you, I lean from the boat -

bird,

ascend to the depths.

(trans. Sasha Dugdale)

The second and third of the poems below are

among the last

Shvarts wrote.

*

How shameful it is to grow

old -

I don't know why,

after all I never made a vow

I wouldn't die

or slip away, my white hairs shining

to the pitch-dark cellar,

nor did I promise myself

I'd stay a child for ever,

but all the same I'm suddenly uneasy -

my withering is plain.

I know why it hurts so much,

but why, oh why, this sense of shame?

(1994)

Sasha Dugdale

On the Street

A mirror's gaze slipped across

me

half-mocking, half-severe

and in it, crooked, staring back

some laughable old dear.

Mirrors have often shown me change

yet in them, always, a face I knew-

till now. It would have seemed less strange

to see a beast come leaping through.

(2010)

Sasha Dugdale

Song

The sun once sang of safety

as it rose above

but then the sun knew nothing

of dark destroying love.

Down swept the sky,

slipped purple on the snows

and the blue tit piped:

your life draws to its close.

(2010)

Sasha Dugdale

En

attendant SN

Âm nhạc của trái cầu

Âm nhạc của trái cầu

Chúng ta chẳng bao giờ

trưởng thành, nhưng cứ thêm tuổi mãi ra, già

mãi ra, rồi già.

Fourteen

She is

still mine—for another year or so—

but she’s

already looking past me

through

the funeral-home door

to where

the boys have gathered in their dark suits.

Mười

bốn

Em vưỡn là của GCC - một

năm nữa, cỡ đó

Nhưng Em đã nhìn quá GCC

Qua cái cửa nhà đòn

Tới cái chỗ đám nhóc trong những

bộ đồ tang tụ tập.

Nếu như thế, cuộc đời của Em chỉ

có, khi có GCC trong đời Em.

Chỉ đến khi, vào những ngày Sài Gòn

đầy biến động, khi làm tờ TSVC, khi có cái số phôn của tòa

soạn, và cũng là số phôn của gia đình, bèn

nhờ Cô Nga, 1 nữ điện thoại viên trên Đài

gọi giùm, và khi hỏi thăm boyfriend, Em cho biết, anh

ấy được lòng Bố em lắm, cứ nghe rục rịch đảo chánh, là

bèn vác mấy bao gao đến nhà cho Bố của em rồi.

Ngưng một lúc thật lâu, rồi Em nói tiếp:

-Gấu không làm được việc đó đâu!

-Đừng bao

giờ nói, mi không xứng đáng!

-Đừng bao giờ nói, mi làm hư tuổi thơ của ta!

Khi tôi gặp chàng

lần đầu tiên, tôi mười một tuổi.

Khi chàng đăm đăm nhìn

tôi, bỗng nhiên tôi nghĩ tới những chữ kỳ lạ như tình

yêu, tình yêu, yêu... và tôi bỗng

bàng hoàng run sợ...

Không,

trăm lần không, ngàn lần không, đừng bao giờ nói

như vậy, đừng bao giờ nói anh không xứng đáng, cũng

đừng bao giờ nói anh làm cho tuổi thơ của Hương bị xáo

trộn

Khi GCC nằm nhà thương Đô Thành, BHD không

dám vô thăm. Đọc báo Chính Luận, thấy

GCC thuộc loại bị thương nặng, khóc, mà không

dám dụi mắt, sợ mắt sẽ đỏ, mọi người trong nhà sẽ

biết. Khi Gấu chuyển vô Grall, ghé thăm đâu cũng

được một, hai lần; một lần, trên đường đi, ghé 1 tiệm

sách ở Lê Lợi, mua 1 cuốn của J.H. Chase, Un beau

matin d’été, Một sáng đẹp mùa hè.

Hỏi, đọc chưa. Gấu ngu quá, nói đọc rồi, em, mặt xịu

xuống, H. cũng nghĩ là anh đọc rồi.

Khi về nhà dưỡng thương, ở hẻm Nguyễn Huỳnh

Đức, Phú Nhuận, có ghé, rồi, khi về Đài

làm việc, với cái tay băng bột, cũng ghé.

Khi tháo băng bột, là mối tình

chấm dứt.

Cái đoạn, chạy theo em, nơi cổng trường

Đại Học Khoa Học, Đại lộ Cộng Hòa, xẩy ra đúng như

vậy. Gấu không thêm bớt, tưởng tượng.

Sau này, nghe qua Vy, cô em họ, em

nói, học Y Khoa mấy năm dài, làm sao bắt anh

Gấu đợi. Mà đợi, thì cũng chắc gì đã nên

vợ, nên chồng. Hơn nữa, anh Gấu, có bằng cấp, công

chức chánh ngạch Bưu Điện, có nhà nhà

nước cấp, lại viết văn nữa, thiếu gì người lo cho anh ấy…

Em tính toán y hệt 1 cô gái

Bắc Kít. Thật là chu đáo. Nhưng lý

do chính, là, em không muốn Gấu phải gọi ông

bố của em là bố!

Nhớ, lần đi chơi trong Chợ Lớn, về, ghé

hình như cũng đường Lê Lợi, để em đi bộ về nhà.

Ra khỏi xe, có một bà và 1 cô gái,

đứng bên hè đường đợi tắc xi, hóa ra là

cô bạn cùng lớp, và bà mẹ của cô.

Cả hai cùng trố mắt nhìn. Gấu hoảng quá. Em tỉnh

bơ, như người Hà Nội, chào, và giới thiệu Gấu,

không phải bạn trai, mà là bạn của ông

anh.

Thật là chững chạc.

Ui chao, sau đọc MCNK, cũng có 1 cảnh y

chang. Nhưng thê lương hơn nhiều.

Và tôi nhớ ra rằng

thì là Giorgio Agamben đã từng giải thích,

với mỗi một thằng cu Gấu ở trong chúng ta, sẽ xẩy ra một cái

ngày, mà vào ngày đó, Bông Hồng

Đen từ bỏ nó.

“Y hệt như là, bất thình lình, trong đêm

khuya, do tiếng động của một băng con nít đi qua cửa sổ của

căn phòng của bạn, và bạn cảm thấy, chẳng hiểu tại ra

làm sao, vì nguyên cớ nào, vị nữ thần, người

nữ muôn đời của bạn, từ bỏ bạn”.

Và nàng nói, “Bây giờ H. hết

lãng mạn rồi!”

Hình như, luôn luôn là, đối với Gấu tôi,

khi đến cõi đời này, là để tìm kiếm trong

giây lát, vị nữ thần của riêng Gấu tôi, vị nữ

thần của một đứa con nít, một thằng bé nhà quê

Bắc Kỳ, thằng bé đó chơi trò chơi phù thuỷ

thứ thiệt của giấc mơ.

Tựa hồn những năm xưa

"Entends, la douce

Nuit qui marche" [Hear, my darling, hear, the sweet Night who

walks]. The silent walking of the night should not be heard.

Baudelaire

She walks in beauty, like the

night

Byron: Hebrew

Melodies (1815):

She walks in beauty, like the

night

Byron: Hebrew Melodies (1815):

Nàng bước trong cái đẹp, như đêm

Borges phán:

Để chấp nhận dòng trên, người đọc

phải tưởng tượng ra một em, cao, tối, tall, dark, bước đi như Đêm,

và Đêm, đến lượt nó, là 1 người đàn

bà cao, tối, và cứ thế, cứ thế.

Tưởng tượng đẩy tưởng tượng,

câu "hót" BHD, thần sầu, "không phải của

GNV", làm nhớ đến lời nhạc thần sầu của TCS, trong Phôi Pha:

Từ vườn khuya bước về

Bàn chân

ai rất nhẹ

Tựa hồn những năm xưa.

BHD ở ngoài đời, cao,

đen, nhập vào với đêm, y chang lời nhạc của TCS

mô tả, những lần "bàn chân ai rất nhẹ, tựa

hồn những năm xưa!"

Lũ Mít, ai không biết, riêng

với GCC, đọc/viết không phải là duyên

mà là... họa!

Cái đọc trước 1975,

là để rước cái họa Lò Thiêu

sau này!

Là, để vào lúc,

tới được Xứ Lạnh, vô thư viện Toronto và cầm lên

cuốn Ngôn ngữ và Câm lặng

của Steiner!

Primo Levi phán

y chang:

Viết và cho xb

Đây có phải là

1 người, và Hưu Chiến, đánh 1

cái dấu quyết định lên đời tôi, không

chỉ như là 1 nhà văn...

Kafka mà không

thế ư. Ông Trời năn nỉ thiếu điều lạy lục tôi,

đừng viết.

NO!

Since then, at an uncertain

hour,

That

agony returns:

And

till my ghastly tale is told,

This

heart within me burns.

Kể từ đó, đâu

biết giờ nào,

Cơn hấp hối đó trở lại,

Và cho tới khi câu chuyện

thê lương của tôi được kể

Trái tim này trong tôi

bỏng rát.

Để "minh họa" cho cái

ý tưởng, cái đọc trước 1975, giống như 1 cuộc xét

nghiệm, the test, của Kafka, hay, như 1 sửa soạn, trained, theo bài

viết trên tờ Guardian, theo đó, can đảm là

phải được rèn luyện, để sau này, ra hải ngoại, được hưởng

cái họa/món quà của Thượng Đế… : Lò

Thiêu, GCC kể chuyện tù VC ở nông trường cải tạo Đỗ

Hòa, Nhà Bè.

The test, the trained, tên tù VC....

"Cho đến khi câu chuyện thê luơng được

kể,

Trái tim này trong GCC bỏng rát"

Đã tính không kể, mang đi theo,

nhưng ông Trời chưa cho đi....

V/v cái họa, món quà…. vị bằng

hữu O. cho biết, nó chỉ là “sự nhẹ nhàng”:

Câu này của OVID, người La Mã,

chết trước Chúa Giêsu khoảng chục năm

Bác tìm câu Mathêu, chương

11, "hãy mang lấy ách của Ta' tìm trong usccb.org

của các giám mục Mỹ, bác sẽ thấy light nghĩa

là nhẹ nhàng.

Hãy đến với Ta, hết thảy những kẻ lao đao

và vác nặng". Và Ta sẽ cho nghỉ ngơi lại sức:

29 Hãy mang lấy ách của Ta vào

mình, hãy thụ giáo với Ta, vì Ta hiền

lành và khiêm nhượng trong lòng, và

các ngươi sẽ tìm thấy sự nghỉ ngơi cho tâm hồn.

30 Vì chưng ách Ta thì êm ái, và

gánh Ta lại nhẹ nhàng".

Bible Mathew chpter 11

27 “All things have been committed to me by my Father.

No one knows the Son except the Father, and no one knows the Father

except the Son and those to whom the Son chooses to reveal him.

28 “Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened,

and I will give you rest. 29 Take my yoke upon you and learn from

me, for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for

your souls. 30 For my yoke is easy and my burden is light.”

28 « Venez à moi, vous tous qui peinez

sous le poids du fardeau, et moi, je vous procurerai le repos.

29 Prenez sur vous mon joug, devenez mes disciples,

car je suis doux et humble de cœur, et vous trouverez le repos pour

votre âme.

30 Oui, mon joug est facile à porter, et mon

fardeau, léger. »

Sách

Báo

Đọc/Viết

mỗi ngày

Picasso and the Fall of Europe

A vision

of Europe in 1950:

Two world

wars in one generation, separated by an uninterrupted chain of local wars

and revolutions, followed by no peace treaty for the vanquished and no

respite for the victor, have ended in the anticipation of a third world

war between the two remaining world powers. This moment of anticipation

is like the calm that settles after all hopes have died. We no longer hope

for an eventual restoration of the old world order with all its traditions,

or for the reintegration of the masses of five continents who have been

thrown into a chaos produced by the violence of wars and revolutions and

the growing decay of all that has still been spared. Under the most diverse

conditions … we watch the development of the same phenomena – homelessness

on an unprecedented scale, rootlessness to an unprecedented depth …

It is as

though mankind had divided itself between those who believe in human omnipotence

(who think that everything is possible if one knows how to organise masses

for it) and those for whom powerlessness has become the major experience

of their lives.

On the level

of historical insight and political thought there prevails an ill-defined,

general agreement that the essential structure of all civilisations is

at breaking point. Although it may seem better preserved in some parts

of the world than in others, it can nowhere provide the guidance to the

possibilities of the century, or an adequate response to its horrors.

The seer is Hannah Arendt, in the 1950

preface to The Origins of Totalitarianism. When she wrote a

new preface to the book in 1966, and looked back for a moment at her

original judgment, she was a touch apologetic. The Origins had

been drafted between 1945 and 1949, and in retrospect it registered,

she had come to feel, as a first effort to understand what had happened

in the opening half of the 20th century, ‘not yet sine ira et studio,

still in grief and sorrow and, hence, with a tendency to lament, but no

longer in speechless outrage and impotent horror’. ‘I left my original

preface in the present edition in order to indicate the mood of those

years.’

I understand

her unease. Already by the mid-1960s, the moment of The Origins of Totalitarianism’s

second edition, the tone and even the substance of her 1950 reckoning

with fascism and Stalinism had a period flavour. The world – or at least,

the world of European and European-in-exile intellectuals – had decided

that the 20th century’s long catastrophe was over. Many thought that 1962,

the year of the Cuban Missile Crisis, had marked its ending. And whatever

crisis of civilisation had succeeded the earlier terrible catastrophe –

Arendt and her friends were far from certain how to characterise the new

situation, and certainly not inclined necessarily to see it as a respite

from ongoing decay and powerlessness at the level of civil society – it

could no longer be written about (or depicted) in epic terms. The fall

of Europe had happened, tens of millions had perished, but the fall of

Europe had not proved a new fall of Troy. After it had not come the savage

god. Maybe ‘the essential structure of civilisation’ had broken; but the

breakage, in the years after 1950, had failed to give rise to a new holocaust

or a final nuclear funeral pyre. In place of the banality of evil had arrived

the banality of Mutually Assured Destruction.

‘Two world

wars in one generation, separated by an uninterrupted chain of local wars

and revolutions’: perhaps it goes without saying that for Arendt’s generation

the revolution that summed up the previous horror – staging, as it had

seemed to, the essential combat between fascism and communism with special

concentrated violence, and drawing into it left and right partisans from

across the world – was the Civil War in Spain. It was, for them, the epic

event of the mid-20th century. Picasso’s Guernica had given it

appropriate, unforgettable form.

The painting

still does, of course. Arendt may have been right to feel a twinge of embarrassment

at the tragic, exalted, ‘catastrophist’ tone of her 1950 preface, and

to have thought by 1966 that the fate of mass societies in the late 20th

century needed to be approached in a different key. But her thinking has

not carried the day. The late 20th century, she argued, would only truly

confront itself in the mirror if it recognised that the battle for heaven

on earth (the classless society, the thousand years of the purified race)

was over. It had given way (this is Arendt’s implication) to a form of

‘mock-epic’ or dismal comedy – still bloodstained and disoriented, but

divested, by the evidence of Auschwitz and the Gulag, of the deadly dream

that everything is possible. And it is this post-epic reality we should

now learn to live with, she believed – maybe even to oppose. We shall only

do this, her 1966 preface says, if we manage to look back on the hell of

the totalitarian period with thorough bemused disillusion. We have to learn

how not to allow the earlier 20th century to stand for the human condition.

We have to detach ourselves from its myth.

But this has

proved impossible. Guernica lives on. Or to put it more carefully:

what is striking about so many 21st-century societies, especially those

involved directly in the wars and revolutions Arendt had in mind, is the

fact that they go on stubbornly living – at the level of myth, of national

self-consciousness, of imagined past and present – in the shadow of an

already distant past. It is their fantasy relation to the struggle of

fascism and communism that continues to give them or rob them of their

identity. Germany remains the prime example, in its interminable double

attachment to (its guilt at and caricature of) the pasts of Nazism and

the Stalinist ‘East’. Russia – with its neo-Bolshevik hyper-nationalism

– is the paranoid case of entrapment for ever in the moment of Stalingrad.

Britain’s endless replaying of its finest hour stands in the way (as it

is meant to) of any real reckoning with the past of empire. (How far, we

might ask, has the UK’s sense of its ‘role in the world’ progressed – been

inflected imaginatively, mimetically, ethically – since the ironies of Kipling

and Conrad?)

Note: Bài

viết này thật tuyệt, nhưng chắc là không làm

sao có thì giờ dịch qua tiếng Mít. Chỉ 1 bức họa mà

gói trọn cả 1 sụp đổ Âu Châu.

Cái viễn ảnh của Âu Châu thập niên 1950, của

Hannah Arendt mà không khủng sao: Hai cuộc thế chiến trong

1 thế hệ.

Bài này, có trên Tin Văn, bản dịch tiếng

Mít

http://tanvien.net/TG_TP/preface_arendt.html

Hannah

Arendt : Những Nguồn Gốc Của Chủ Nghĩa Toàn Trị.

Lời Tựa

lần xuất bản đầu (1951).

Weder

demVergangenen anheimfallen noch

dem Zukunftigen.

Es kommt darauf an, ganz gegenwartig zu sein.

K. Jaspers

Chớ đắm

đuối hoài vọng quá khứ, hoặc tương lai.

Điều

quan trọng là hãy trọn vẹn ở trong hiện tại.

Karl

Jaspers. (1)

Hai thế chiến trong một thế hệ - phân cách nhau là

một chuỗi không dứt những chiến tranh và cách mạng địa

phương, tiếp theo sau không hòa ước cho kẻ thua mà cũng

chẳng thảnh thơi cho kẻ thắng – đã kết thúc trong cảnh thập

thò của cuộc Thế Chiến Thứ Ba giữa hai cường lực thế giới còn

lại. Khoảnh khắc thập thò này giống như sự bình lặng

dấy lên sau khi mọi hy vọng vừa chết. Chúng ta không

còn hy vọng tái lập thật rốt ráo cái trật tự

thế giới cũ với tất cả truyền thống của nó, hoặc tái phục

nguyên khối quần chúng năm châu, bị ném vào

cuộc hỗn mang do bạo động chiến tranh và cách mạng gây

nên, và cuộc hủy diệt dần những gì còn sót

lại. Ở trong những điều kiện phức biệt nhất, những hoàn cảnh dị biệt

nhất, chúng ta theo dõi cùng những hiện tượng cứ thế

phát triển: hiện tượng bán xới trên một qui mô

chưa từng có trước đây, và hiện tượng mất gốc chưa bao

giờ tới độ sâu như vậy.

Chưa bao giờ tương lai của chúng ta lại mập mờ đến như thế,

chưa bao giờ chúng ta lại lệ thuộc đến như thế vào những

quyền lực chính trị; chẳng thể nào tin cậy, rằng chúng

sẽ tuân thủ qui luật "lợi cho mình nhưng đừng hại cho người";

những sức mạnh thuần chỉ là điên rồ, nếu xét theo tiêu

chuẩn những thế kỷ khác. Tuồng như thể nhân loại tự phân

ra, một bên là những kẻ tin ở sự toàn năng của con người

(những kẻ tin rằng mọi sự đều khả dĩ nếu người ta biết cách tổ chức

quần chúng thực hiện theo đường lối đó), một bên là

những kẻ mà sự bất lực đã trở thành kinh nghiệm chủ

chốt trong đời họ.

Trên bình diện kiến giải lịch sử và tư duy chính

trị, trội hẳn lên là một kiểu thỏa thuận chung, [tuy] không

được định nghĩa rõ ràng: rằng cấu trúc thiết yếu của

tất cả văn minh đang ở điểm đứt đoạn. Mặc dù có vẻ được gìn

giữ khá hơn ở một số nơi trên thế giới so với những nơi khác,

chẳng nơi nào nó có thể đem đến cho chúng ta

một sự hướng dẫn, nếu nói về những khả tính - hoặc một phản

ứng tới nơi tới chốn, trước những điều ghê gớm tởm lợm - của thế kỷ.

Một khi [con người] tới gần trái tim của những biến cố như thế, thay

vì một phán đoán quân bình, một kiến giải

thận trọng, thì lại là hy vọng tuyệt vọng, và sợ hãi

tuyệt vọng. Những biến động trung tâm của thời đại chúng ta

được lãng quên thật hiệu quả, bởi những người đắm mình

vào một niềm tin, rằng tận thế không thể nào tránh

được, hơn là bởi những người buông xuôi vào một

chủ nghĩa lạc quan liều lĩnh.

Dựa lưng vào một niềm lạc quan liều lĩnh và một tuyệt

vọng liều lĩnh, cuốn sách này được viết trong một bối cảnh

như thế đó. Cuốn sách khẳng định: rằng Tiến Bộ và Tận

Thế là hai mặt, của vẫn một huân chương; rằng cả hai đều là

những điều này mục nọ của mê tín, không phải của

niềm tin. Nó đã được viết ra, từ một xác tín,

là có thể khám phá những cơ chế ẩn giấu, theo

đó, toàn bộ những thành tố truyền thống của thế giới

chính trị và tâm linh của chúng ta bị tan biến

vào một lò cừ, nơi mọi sự dường như mất đi giá trị

đặc thù của nó, trở thành lạ lẫm đối với nhận thức

của con người, trở thành vô dụng cho những mục tiêu của

con người. Một cám dỗ khó đề kháng - chịu khuất mình

vào một quá trình thuần túy, giản dị của sự

băng hoại, không chỉ là vì nó khoác lên

cho sự vĩ đại hồ đồ - tức cái gọi là "tất yếu lịch sử" - một

bộ áo mã, mà còn là vì điều này:

tất cả mọi sự, ở bên ngoài nó, đều có vẻ như

thiếu sống, thiếu máu, vô nghĩa, và không thực.

Mọi chuyện xẩy ra ở trên cõi đời này phải "được

hiểu" đối với con người, một xác tín như thế sẽ đưa đến chuyện

giải thích lịch sử bằng những khuôn sáo. Nhưng "hiểu"

không có nghĩa là từ chối cái nghịch thường,

hoặc diễn dịch một điều chưa hề xẩy ra bằng tiền lệ, hoặc giải thích

hiện tượng bằng loại suy và bằng tổng quát, khiến con người

trơ ra, khi đụng đầu, và kinh nghiệm thực tại. Thay vì vậy,

nó có nghĩa, quan sát, nghiên cứu, ý thức

được cái gánh nặng mà thế kỷ này đã đặt

lên chúng ta – không phủ nhận sự hiện hữu, mà cũng

không cam chịu sức nặng của nó. Như vậy, "hiểu" có nghĩa

là giáp mặt thực tại, không tính toán

trước, nhưng chú tâm, và đề kháng lại nó,

bất kể nó ra sao.

Theo nghĩa đó, phải đối mặt và hiểu được sự kiện ngược

ngạo: rằng một hiện tượng nhỏ nhoi như thế (vàchẳng có chi

là quan trọng như thế, đối với chính trị thế giới): hiện tượng

vấn đề Do Thái và chủ nghĩa bài Do Thái lại

có thể trở thành tác nhân của, đầu tiên

là phong trào Quốc Xã, rồi sau đó, thế chiến,

và sau chót, cho việc thiết lập những xưởng máy của

cái chết. Hoặc, sự sai biệt lố bịch giữa nhân và quả

mở ra kỷ nguyên của chủ nghĩa tư bản, khi những khó khăn kinh

tế, trong vài thập niên, dẫn tới một biến đổi sâu xa tình

hình chính trị trên toàn thế giới. Hay, sự mâu

thuẫn kỳ quặc giữa cái chủ nghĩa hiện thực trơ tráo tuyên

xưng của những phong trào toàn trị và sự miệt thị lồ

lộ của chúng, đối với toàn bộ mạng lưới thực tại. Hoặc, sự

bất tương xứng nhức nhối giữa quyền năng thực sự của con người hiện đại (lớn

hơn bao giờ hết, lớn đến mức có thể thách thức ngay cả sự hiện

hữu của vũ trụ) và nỗi bất lực mà con người hiện đại phải sống,

và phải tìm ra cái ý nghĩa của cái thế

giới do nó tạo nên, bằng chính sức mạnh năng vô

biên của nó.

Toan tính toàn trị - chinh phục toàn cầu, thống

trị toàn diện – là một phương thức mang tính hủy diệt,

nhằm vượt ra ngoài mọi ngõ cụt. Thành công của

nó có thể trùng khớp với sự hủy diệt nhân loại;

ở nơi nào nó cai trị, ở nơi đó hủy diệt bản chất của

con người. Hỡi ơi, nhắm mắt bưng tai, quay lưng lại với những sức mạnh

hủy diệt của thế kỷ này thì cũng chẳng đi đến đâu.

Thực vậy, đây là nỗi khốn khó của thời đại chúng

ta, mắc míu lung tung, đan xen lạ lùng giữa xấu và

tốt, đến nỗi, nếu không có "bành trướng để bành

trướng" của những tên đế quốc, thế giới chẳng bao giờ trở thành

một; nếu không có biện pháp chính trị "quyền

lực chỉ vì quyền lực" của đám tư sản, cái sức mạnh

vô biên của con người chắc gì đã được khám

phá; nếu không có thế giới ảo vọng, thiên đường

mù của những phong trào toàn trị, qua đó, những

bất định thiết yếu của thời đại chúng ta đã được bầy ra một

cách thật rõ nét, như chưa từng được bầy ra như vậy,

thì làm sao chúng ta [lại có cơ hội] bị đẩy tới

mấp mé bên bờ tận thế, vậy mà vẫn không hay, chuyện

gì đang xẩy ra?

Và nếu thực, là, trong những giai đoạn tối hậu của chủ

nghĩa toàn trị, một cái ác triệt để xuất hiện, (triệt

để bởi vì chúng không thể suy diễn ra, từ những động

cơ có thể hiểu được, của con người), thì cũng thực, là,

nếu không có chủ nghĩa toàn trị, chúng ta có

thể chẳng bao giờ biết được bản chất thực sự cơ bản, thực sự cội rễ, của

cái ác.

Chủ nghĩa bài Do Thái (không phải chỉ có

sự hận thù người Do Thái không thôi), chủ nghĩa

đế quốc (không chỉ là chinh phục), chủ nghĩa toàn trị

(không chỉ là độc tài) – cái này tiếp

theo cái khác, cái này bạo tàn hơn cái

kia, tất cả đã minh chứng rằng, phẩm giá của con người đòi

hỏi một sự đảm bảo mới, và sự đảm bảo mới mẻ này, chỉ có

thể tìm thấy bằng một nguyên lý chính trị mới,

bằng một lề luật mới trên trái đất này; sự hiệu lực

của nó, lần này, phải được bao gồm cho toàn thể loài

người, trong khi quyền năng của nó phải được hạn chế hết sức nghiêm

ngặt, phải được bắt rễ, và được kiểm soát do những thực thể

lãnh thổ được phân định mới mẻ lại.

Chúng ta không còn thể cho phép chúng

ta giữ lại những cái gì tốt trong quá khứ, và

đơn giản gọi đó là di sản của chúng ta, hay loại bỏ

cái gì là xấu, giản dị coi đó là một

gánh nặng chết tiệt mà tự thân chúng sẽ bị thời

gian chôn vùi trong lãng quên. Cái mạch

ngầm của lịch sử Tây phương sau cùng đã trồi lên

trên mặt đất, và soán đoạt phẩm giá của truyền

thống của chúng ta. Đây là thực tại chúng ta

sống trong đó. Đây là lý do tại sao mọi cố gắng

chạy trốn cái u ám của hiện tại, bằng hoài vọng một

quá khứ vẫn còn trinh nguyên, hay bằng một sự lãng

quên có dự tính về một tương lai tốt đẹp hơn: tất cả

những cố gắng như vậy đều là vô hiệu.

Hè 1950

Hannah Arendt

NQT chuyển ngữ.

Chú thích:

Cuốn Những Nguồn Gốc Của Chủ Nghĩa

Toàn Trị, trước đây, khi dịch ra tiếng Pháp,

đã được phân làm ba. Vì vậy, thiếu Lời Tựa. Lần

này, nhà xb Gallimard đã đem đến cho nó một

bản dịch toàn thể; cùng với tác phẩm "Eichmann ở Jérusalem", cả hai

được in chung thành một tập, trong tủ sách Quarto. Như thế,

Lời Tựa lần xuất bản đầu tiên bằng tiếng Anh (1951), lần thứ nhất ra

mắt độc giả tiếng Pháp, trên tạp chí Văn Học, Le Magazine Littéraire, số Tháng

Sáu, 2002.

Do tính quan trọng của bản văn, và sự chính xác

của nó, chúng tôi có cho "scan" nguyên

bản tiếng Anh và bản dịch tiếng Pháp trên trang Tin Văn,

để độc giả tiện tham khảo.

Picasso’s mural for Unesco’s headquarters

in Paris.

Literary history

Born to be Wilde

Oscar Wilde came from a wild

and eccentric family

Fine and dandyThe

Fall of the House of Wilde. By Emer O’Sullivan. Bloomsbury;

495 pages; £25. To be published in America in October; $35.

AS A child,

Oscar Wilde announced that he would like to be remembered as the hero

of a “cause célèbre and to go down

to posterity as the defendant in such a case as ‘Regina Versus Wilde’”.

He succeeded, of course, and his notoriety poses a problem for biographers

unlikely to discover anything new about the great aesthete. They increasingly

turn to the lesser-canonised figures in his sphere; in 2011 came Franny

Moyle’s account of Wilde’s wife, Constance Lloyd. Then “Wilde’s Women”

by Eleanor Fitzsimons. Now Emer O’Sullivan, the author of a new book

“The Fall of the House of Wilde”, places Oscar in the context of his

immediate family, stating that “it is to No.1 Merrion Square we need

to look for the formation of Oscar’s mind.”

This approach

can reap rewards. Some familial ties are plain to see; Oscar’s renowned

style and turn of phrase finds its origins in his mother, Jane; she

deplores those who “paraphrase a Poet into the prose of everyday life”

and rebukes the subtitle of “Lady Windermere’s Fan” on the grounds that

“no one cares for a good woman.” Jane’s salons attracted intellectual

figures, with attendants seeking to display their wit and conversational

skill. Oscar emulated these events—notably in his drawing-room dramas,

where style was paramount—but also in his salons, named “Tea and Beauties”,

in London.

The Wildes

prized independent thinking. Sir William, a renowned polymath and

doctor, controversially advocated interracial coupling, arguing that

it encouraged diversity of thought and the progression of society. His

wife Jane wrote poems raging with republican spirit, felt passionately

about the “bondage of women” and translated a deeply unpopular work

on temptation. Oscar inherited this sense of intellectual daring and

the need to push boundaries. In one of his first pieces of professional

writing, he praises the patent homoeroticism of paintings by Spencer

Stanhope. Other reviewers, likely fearful of social condemnation, turned

a blind eye.

Yet Ms O’Sullivan

often strains to make parallels that aren’t there. Much is made,

for example, of Oscar’s affair with Robbie Ross, two years into his

marriage with Lloyd. This is the exact time, Ms O’Sullivan notes, at

which a patient of William’s called Mary Travers aroused suspicion

from Jane. According to Ms O’Sullivan, this may be an echo of the memory

or significant “of an order underlying the chaos of human relationships”.

That father and son shared a wandering eye does not warrant such sweeping

statements.

At the same

time, obvious parallels are ignored or suffer from a lack of information.

Jane’s lifelong interest in women’s rights and the undervalued intellects

of wives surely influenced Oscar’s decision to edit Woman’s World, a magazine which provided more varied

reading material for an emerging class of educated women. How his family

responded to Oscar’s trial and imprisonment—the climax of any biography

of the writer—readers can only guess: “what Jane or Willie [Oscar’s

brother] thought about Oscar’s pending trial is nowhere recorded.” Similarly,

the impact of the trial upon Oscar’s children—who dropped the surname “Wilde”

as a result of the scandal—is barely mentioned.

Readers may

finish the book longing for more detail on Jane Wilde, who is repeatedly

lauded as a literary force in her own right (though with little textual

support). It is her fate that is the most disquieting. Oscar achieved

his aim to be remembered by history—his grave in Paris is a site of

pilgrimage. Jane, however, paid the price of his fame. Once voted the

greatest living Irishwoman by her contemporaries, Jane Wilde was buried

in poverty “without fanfare—without name or record…in soil to which

she did not belong”.

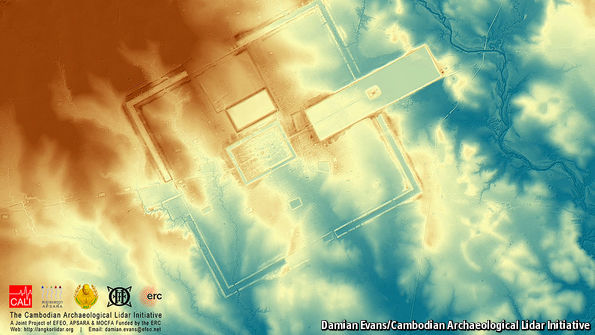

Cambodia

Buried treasure

It may not

look like much now, but in the 12th century, Preah Khan of Kompong

Svay (pictured) was part of the world’s largest urban settlement and

one of its most powerful empires. Found beneath the forest floor near

Angkor Wat using lidar (like radar, but with lasers), these cities

of the Khmer Empire show complex water systems built centuries before

the underlying technology was believed to have existed, as well as highways

connecting major settlements. The lack of evidence of a substantial relocated

population nearby casts doubt on the widely accepted theory that the

Khmer Empire collapsed when the Siamese invaded. More maps will be published

in the coming months.

Đế Quốc Khờ Me dưới lòng đất

My Old Saigon

Chắc cũng gần tòa soạn

báo Văn

https://www.flickr.com/photos/13476480@N07/27134222114/in/photostream/

|

Trang NQT

art2all.net

Lô

cốt

trên

đê

làng

Thanh Trì,

Sơn Tây

|

|