Nguyễn Quốc Trụ

Sinh 16 tháng Tám,

1937

Kinh

Môn,

Hải Dương

[Bắc

Việt]

Quê

Sơn

Tây

[Bắc

Việt]

Vào

Nam

1954

Học

Nguyễn

Trãi

[Hà-nội]

Chu Văn An,

Văn Khoa

[Sài-gòn]

Trước

1975

công

chức

Bưu

Điện

[Sài-gòn]

Tái

định

cư năm

1994

Canada

Đã

xuất

bản

Những

ngày

ở Sài-gòn

Tập

Truyện

[1970,

Sài

Gòn,

nhà

xb Đêm

Trắng

Huỳnh

Phan

Anh

chủ

trương]

Lần

cuối,

Sài-gòn

Thơ,

Truyện,

Tạp

luận

[Văn

Mới,

Cali.

1998]

Nơi

Người

Chết

Mỉm Cười

Tạp

Ghi

[Văn

Mới,

1999]

Nơi

dòng

sông

chảy

về phiá

Nam

[Sài

Gòn

Nhỏ,

Cali,

2004]

Viết

chung

với

Thảo

Trần

Chân

Dung

Văn Học

[Văn

Mới,

2005]

Trang Tin Văn, front page, khi quá đầy,

được

chuyển

qua Nhật

Ký

Tin Văn,

và

chuyển

về

những

bài

viết

liên

quan.

*

Một

khi

kiếm,

không

thấy trên

Nhật

Ký,

index:

Kiếm

theo

trang

có

đánh

số.

Theo

bài

viết.

Theo

từng

mục,

ở đầu trang

Tin

Văn.

Email

Nhìn

lại

những trang

Tin

Văn

cũ

1

2

3

4

5

Bản quyền Tin Văn

*

Tất

cả bài

vở

trên

Tin Văn,

ngoại

trừ

những

bài

có

tính

giới

thiệu,

chỉ

để sử dụng

cho cá

nhân

[for personal

use], xài

thoải

mái

[free]

Liu

Xiaobo

Elegies

Nobel

văn

chương

2012

Anh

Môn

Kỷ niệm 100 năm sinh của Milosz

IN MEMORIAM

W. G. SEBALD

http://tapchivanhoc.org

|

Kepler khám phá ra,

mặt trời là định tinh, và những vì sao khác,

như trái đất, mặt trăng… quay quanh mặt trời, từ 1 cảm quan

tôn giáo:

Chúa ban ánh sáng tới cho muôn loài.

Ngược hẳn Gấu Cà Chớn.

Gấu phát giác ra, những cái đọc trước 1975, là

để sửa soạn đón nhận cái họa Lò Thiêu, là

từ cảm quan “đói”, những ngày tù Đỗ Hòa!

Phải đến khi về già, nhìn lại, Gấu mới hiểu ra 1 điều

thật là tầm thường giản dị:

Giả như là Gấu có được cái ân sủng, là

1 tên Ky Tô, thì đời Gấu khác hẳn.

Bởi là vì rõ ràng là, Chúa

quá quan tâm đến 1 tên vô đạo là Gấu Cà

Chớn, tếu thế!

Cái gì gì:

Em linh hồn vô tội

Đeo thánh giá huy hoàng

Anh 1 đời sám hối.

Mà sao vẫn hoang đàng!

Lần đầu nghe

bản nhạc, là ở trong tù Đỗ Hòa.

Nghe 1 phát, là bủn rủn chân tay..... (1)

(1) Gấu có một bài viết,

cứ ấp ủ mãi, mà không làm sao viết ra được,

cho đến lúc thấy cái tít kỷ niệm 5 năm talawas !

Bài viết liên can đến một bài hát, Gấu

nghe, lần đầu trong đời, những ngày ở trại lao động cải tạo Đỗ Hòa,

Cần Giờ.

Chuyện Tình Buồn.

Có hai tay ca bài này thật là tới, một

là bạn thân của Gấu, Sĩ Phú, và một, Tuấn Ngọc.

Năm năm trời không gặp,

Được tin em lấy chồng...

..

Anh một đời rong ruổi,

Em tay bế tay bồng...

Chả là, trước khi bị tóm, bị tống đi lao động cải tạo,

một buổi tối, Gấu nhớ cô bạn quá, mò tới con hẻm ngày

xưa, đứng thật xa nhìn vô căn nhà, lúc đó

cũng đã tối, thành thử cũng chẳng ai thèm để ý,

và Gấu thấy cô bạn ngày nào đang đùa

với mấy đứa con, đứa bò, đứa nằm dưới sàn nhà, tay

cô thì bận một đứa nữa.

Cảnh này, cứ mỗi lần nghe bản nhạc là lại hiện ra,

ngay cả những ngày sắp sửa đi xa như thế này....

Thế mới thảm !

Thế mới nhảm !

Thế mới chán ! NQT

Nhật Ký

64

***

GyorgyFaludy

(Hungary- mất ngày 1 Tháng Chín, 2006, thọ 95 tuổi)

chọn nhà tù. Ông đã được đề nghị, một cơ may,

chạy trốn quê hương, qua Áo định cư, nhưng từ chối, và

lý luận, rằng, tôi phải tận mắt chứng kiến, những đau khổ,

những rùng rợn, cho dù tới cỡ nào, mà những người

Cộng Sản mơ tưởng ra được, cho xứ sở của tôi

Không có viết và mực, ở trong trại tập trung Stalinist

tại Hung, Gyorgy Faludy dùng cọng chổi để viết, bằng máu,

và trên giấy vệ sinh. Đau khổ, như một lần ông nói,

không phải là một đức hạnh. Nhưng ba năm của ông tại Recsk,

từ 1950 đến 1953, theo một nghĩa nào đó, quả là những

năm tháng mặc khải. Tập thơ xuôi, "tản văn", như lối nói

hiện nay, nổi tiếng ở bên ngoài nước Hung, kể lại quãng

đời hưng phấn một cách âm u đó, darkly inspiring, tức

thời gian ông ở tù được ông đặt tên là “Những

Ngày Hạnh Phúc Của Tôi Ở Địa Ngục.

Note: Những ngày ở Đỗ Hòa của Gấu, 1 cách nào

đó, cũng là những ngày hạnh phúc. Gấu làm

báo nông trường, làm Y Tế Đội, nhờ lần thăm nuôi

đầu tiên và cũng là cuối cùng của Gấu Cái.

Những lần sau, bà cụ Gấu lo, tháng 1 lần, trong hai năm trời....

Thơ

Mỗi

Ngày

A Happy Love

A happy love. Is

it normal,

is it serious, is it profitable-

what use to the world are two people

who have no eyes for the world?

Elevated each for each, for no apparent merit,

by sheer chance singled out of a million, yet convinced

it had to be so-as reward for what? for nothing;

the light shines from nowhere-

why just on them, and not on others?

Is this an offense to justice? Yes.

Does it violate time-honored principles, does it cast

any moral down from the heights? It violates and casts down.

Look at the happy couple:

if they'd at least dissemble a bit,

feign depression and thereby cheer their friends!

Hear how they laugh-offensively.

And the language they speak-it only seems to make sense.

And all those ceremonials, ceremonies,

those elaborate obligations toward each other-

it all looks like a plot behind mankind's back!

It's even hard to foresee how far things might go,

if their example could be followed.

What could religions and poetries rely on,

what would be remembered, what abandoned,

who would want to keep within the bounds.

A happy love. Is it necessary?

Tact and common sense advise us to say no more of it

than of a scandal in Life's upper ranks.

Little cherubs get born without its help.

Never, ever could it populate the earth,

for it happens so seldom.

Let people who know naught of happy love

assert that nowhere is there a happy love.

With such faith, they would find it easier to live and to die.

Under a Certain Little Star

I apologize to coincidence for calling it necessity.

I apologize to necessity just in case I'm mistaken.

Let happiness be not angry that I take it as my own.

Let the dead not remember they scarcely smoulder in my

memory.

I apologize to time for the muchness of the world overlooked per

second.

I apologize to old love for regarding the new as the first.

Forgive me, far-off wars, for bringing flowers home.

Forgive me, open wounds, for pricking my finger.

I apologize to those who cry out of the depths for the minuet-

record.

I apologize to people at railway stations for sleeping at five in

the morning.

Pardon me, hounded hope, for laughing now and again.

Pardon me, deserts, for not rushing up with a spoonful of water.

And you, O falcon, the same these many years, in that same

cage,

forever staring motionless at that self-same spot,

absolve me, even though you are but a stuffed bird.

I apologize to the cut-down tree for the table's four legs.

I apologize to big questions for small answers.

O Truth, do not pay me too much heed.

O Solemnity, be magnanimous unto me.

Endure, mystery of existence, that I pluck out the threads of

your train.

Accuse me not, O soul, of possessing you but seldom.

I apologize to everything that I cannot be everywhere.

I apologize to everyone that I cannot be every man and woman.

I know that as long as I live nothing can justify me,

because I myself am an obstacle to myself.

Take it not amiss, O speech, that I borrow weighty words,

and later try hard to make them seem light.

The Suicide's Room

You certainly think

that the room was empty.

Yet it had three chairs with sturdy backs.

And a lamp effective against the dark.

A desk, on the desk a wallet, some newspapers.

An un sorrowful Buddha, a sorrowful Jesus.

Seven good-luck elephants, and in a drawer a notebook.

You think that our addresses were not there?

You think there were no books, pictures, records?

But there was a consoling trumpet in black hands.

Saskia with a heartfelt flower of love.

Joy the fair spark of the gods.

Odysseus on the shelf in life-giving sleep

after the labors of Book Five.

Moralists,

their names imprinted in syllables of gold

on beautifully tanned spines.

Right next, statesmen standing straight.

And not without a way out, if only through the door,

not without prospects, if only through the window,

that is how the room looked.

Distance glasses lay on the windowsill.

A single fly buzzed, that is, was still alive.

You think at least the note made something clear.

Now what if I tell you that there was no note-

and so many of us, friends of his, yet all could fit

in the empty envelope propped against the glass.

Transtromer

Page

TTT 10 years Tribute

C uốn này, thấy lâu rồi,

nhưng không dám đụng vô. Bìa

cứng, xót tiền quá, và đọc,

thì cũng cực quá.

Nhân

Tết Mít, bèn bệ về, vì, cũng

có ý, đi 1 đường tưởng niệm ông anh

nhà thơ, bằng cái bài của bà

nữ phê bình TK "Yankee mũi lõ" này,

về Langston Hughes.

Lần

đầu GCC nghe cái tên ông nhà

thơ da đen này, là qua thơ TTT.

Nghê

thuật đen.

Đen,

với ông anh là da đen, là Jazz...

Nhưng

với GCC, là… cơm đen!

Như cái

note dưới đây

Suicide's Note:

The calm,

Cool

face of the river

Asked

me for a kiss

*

Christ is a nigger,

Beaten and

black:

Oh, bare

your back!

Mary is His

mother:

Mammy of

the South,

Silence your

mouth.

God is His

father:

White Master

above

Grant Him

your love.

Most holy

bastard

Of the bleeding

mouth,

Nigger Christ

On the cross

Of the South

Christ là tên mọi đen

Bị đánh đập, và đen:

Ôi, trật cái lưng ra đây!

Mary là Má của Nó,

Nam Kít

Hãy câm miệng!

Chúa của Nó

Da trắng ở trên Trời

Ban cho Nó tình yêu

Ôi đứa con hoang kia ơi

Miệng đầy máu

Christ da đen

Trên thập tự

Christ, Nam Kít!

*

The saxophone

Has a vulgar

tone.

I wish it

would

Let me alone.

The saxophone

Is ordinary.

More than

that,

It's mercenary!

The saxophone's

An instrument

By which

I wish

1'd never

been

Sent!

*

Me and the Mule

My old mule,

He's got

a grin on his face.

He's been

a mule so long

He's forgot

about his race.

I'm like

that old mule-

Black-and

don't give a damn!

You got to

take me

Like I am.

Helen Vendler: The Unweary Blues. The Collected Poems of Langston

Hughes

[in The Ocean, the Bird and the Scholar]

Semyon Lipkin (I911-2003)

Born

in Odessa, Semyon Israilievich Lipkin moved to Moscow in 1929. Unable

from 1934 to publish his own work, he turned to translating, mainly from

Persian and the Turkic languages of Central Asia. His first collection

of his own poetry appeared only in 1967. He also wrote a novel about Stalin's

deportation of the Chechens, and a memoir of Vasily Grossman. It was

Lipkin who initiated the process that led to the text of Grossman’s Life

and Fate being smuggled out to the West.

By the Sea

The waves crashed under the flicker of the lighthouse

and I, in my ignorance, heard a monotone.

Years later the sea speaks to me and I begin to understand

there are birds and laundresses, sprites and sorcerers,

laments and curses, moans and profanity, white horses

and half breeds who rear up unexpectedly.

There are waves who are salesgirls with buxom hips

who sell foam from the counter, they tremble fluent or airy.

Nature can't be indifferent, she always mimics us

like a loan, a translation; we're the blueprint, she's the

copy.

Once upon a time the pebble was different

and so the wave was different.

(1965)

Yvonne Green

*

He

who gave the wind its weight,

and gave measure to the water,

pointed lightning on its path,

and showed rain what rules to follow -

he once told me with quiet joy:

'No one's ever going to kill you:

How can dust be broken down?

Who has power to ruin beggars?'

(1981)

Robert Chandler

Nhờ Lipkin mà Tây Phương được đọc tuyệt tác

Đời và Số Phận của Vasily Grossman

Bác

đọc quyển này chưa – 832 trang, bây giờ bán ở format

de poche rồi. Bác cốp theo kiểu này viết đi, lồng trong

chế độ là cảnh đời của người dân. Bác có trí

nhớ phi thường, bác không viết thì ai mà viết

được.

Tks

NQT

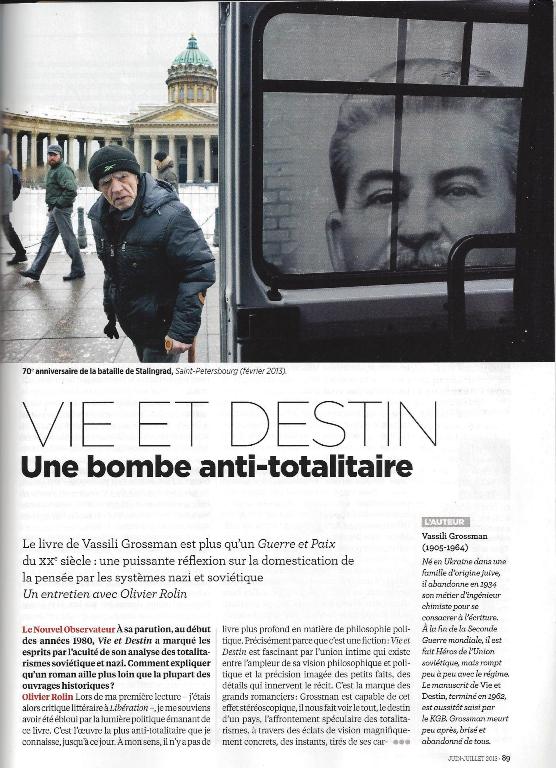

"Mort de l'esclave

et réssurection de l'homme libre".

Dans ce roman-fresque,

composé dans les années 1950, à la façon

de Guerre et paix,

Vassili Grossman (1905-1964) fait revivre l'URSS en guerre à

travers le destin d'une famille, dont les membres nous amènent

tour à tour dans Stalingrad assiégée, dans les

laboratoires de recherche scientifique, dans la vie ordinaire du peuple

russe, et jusqu'à Treblinka sur les pas de l'Armée rouge.

Au-delà de ces destins souvent tragiques, il s'interroge sur la

terrifiante convergence des systèmes nazi et communiste alors

même qu'ils s'affrontent sans merci. Radicalement iconoclaste

en son temps - le manuscrit fut confisqué par le KGB, tandis

qu'une copie parvenait clandestinement en Occident -, ce livre pose

sur l'histoire du XXe siècle une question que philosophes et historiens

n'ont cessé d'explorer depuis lors. Il le fait sous la forme d'une

grande œuvre littéraire, imprégnée de vie et d'humanité,

qui transcende le documentaire et la polémique pour atteindre

à une vision puissante, métaphysique, de la lutte éternelle

du bien contre le mal.

Destin de Grossman

Vie

et destin est l'un des chefs-d'oeuvre du XXème siècle.

On n'en lisait pourtant qu'une version incomplète depuis que les

manuscrits avaient été arrachés au KGB et à

la censure. Celle que Bouquins propose désormais est la

première intégrale. Elle a été révisée

à partir de l'édition russe qui fait désormais autorité,

celle de 2005, et traduite comme la précédente par Alexis

Berelowitch et Anne Coldefy-Faucard. Raison de plus pour se

le procurer. Ce volume sobrement intitulé Oeuvres (1152

pages, 30 euros) contient également une dizaine de nouvelles, le

roman Tout passe, texte testamentaire qui dresse notamment

le portrait d'une série de Judas, et divers documents dont une

lettre à Kroutchtchev. Mais Vie et destin, roman

dédié à sa mère par un narrateur qui s'adresse

constamment à elle, demeurera l'oeuvre qui éclipse toutes

les autres. La bataille de Stalingrad est un morceau d'anthologie, et,

au-delà de sa signfication idéologique, la manière

dont l'auteur passe subrepticement dans la ville de l'évocation

du camp nazi au goulag soviétique est un modèle d'écriture.

Toute une oeuvre parue à titre posthume.

Dans son éclairante préface, Tzvetan

Todorov résume en quelques lignes "l'énigme" de Vassili Grossman (1905-1964)

:

" Comment se fait-il

qu'il soit le seul écrivain soviétique connu à

avoir subi une conversion radicale, passant de la soumission à

la révolte, de l'aveuglement à la lucidité ? Le

seul à avoir été, d'abord, un serviteur orthodoxe

et apeuré du régime, et à avoir osé, dans

un deuxième temps, affronter le problème de l'Etat totalitaire

dans toutes son ampleur ?"

On songe bien sûr

à Pasternak et Soljenitsyne. Mais le préfacier,

anticipant la réaction du lecteur, récuse aussitôt

les comparaisons au motif que le premier était alors un écrivain

de premier plan et que la mise à nu du phénomène

totalitaire n'était pas au coeur de son Docteur Jivago

; ce qui n'est évidemment pas le cas du second avec Une Journée

d'Ivan Denissovitch, à ceci près rappelle Todorov,

qu'étant un inconnu dans le milieu littéraire, il n'avait

rien à perdre. La métamorphose de Grossman

est donc un cas d'école unique en son genre :"mort de l'esclave et réssurection

de l'homme libre".

Bảnh hơn Pasternak, bảnh hơn

cả Solzhenitsyn, Tzvetan Todorov, trong lời tựa, thổi Đời & Số Mệnh của Grossman: Cái

chết của tên nô lệ và sự tái sinh của con

người tự do.

Tờ Obs, số đặc biệt về những tuyệt tác của văn học,

kể ra hai cuốn cùng dòng, là Gulag của Solz, 1 cuốn sách

lật đổ 1 đế quốc, và Vie & Destin

của Grossman: Trái bom chống toàn

trị.

TV sẽ giới thiệu bài phỏng vấn Ovivier Rolin, trên

tờ Obs.

Why even poets hate poetry

The Hatred of Poetry.

By Ben Lerner. Farrar, Straus & Giroux; 86 pages; $12. Fitzcarraldo;

£9.99.

POETRY has

always occupied an ambivalent space in society. In the ancient world

Plato banned poets from his ideal republic; today they have to navigate

the “embarrassment or suspicion or anger” that follows when they

admit to their profession in public. Ben Lerner understands this hatred:

as a poet he has been on the receiving end of it, but also, more interestingly,

he has felt it himself.

Long before

he published his two acclaimed novels, “Leaving the Atocha Station” and “10:04”,

Mr Lerner was known as a poet. Yet the biographical details that are woven

into this short and spirited discussion suggest an uneasy relationship with

the form. As a boy, charged with learning a poem, Mr Lerner tried to game

the system by asking his librarian which was the shortest; later in life

he confesses that he has never heard what Sir Philip Sidney described as

“the planet-like music of poetry”, nor experienced the “trance-like state”

widely said by critics to be induced by John Keats (“I’ve never seen any

critic in a trance-like state,” he adds, not unfairly.)

Yet Mr Lerner

does not see all this as a problem; indeed, he believes it to be

central to the art form. Poets and non-poets alike hate poetry, he

argues, because poetry will always fail to deliver on the transcendental

demands people have invested in it. As a result they enjoy pronouncing

upon the abstract powers and possibilities of poetry more than they

actually like to sit down and read it. As Keats wrote in “Ode on a Grecian

Urn”, “Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard/Are sweeter.” Mr

Lerner takes his cue from Keats, but is a little more frank when he

describes “the fatal problem with poetry: poems”.

This inevitable

sense of falling short is expressed in some of the best poetry ever

written, he says, and he elaborates his point with energised discussions

of Keats, Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson. But it is also inadvertently

present in some of the worst poetry ever written. “Alas! I am very

sorry to say/That 90 lives have been taken away”, wrote William Topaz

McGonagall, a Scottish poet, in a notoriously underwhelming response

to the Tay Bridge disaster of 1879. “When called upon to memorialise

a faulty bridge, McGonagall constructs another,” writes Mr Lerner,

as he dissects McGonagall’s swirling metrical confusion with poetically

informed glee across a number of pages.

But McGonagall’s

literary ineptitude is well known, and Mr Lerner’s essay becomes

most interesting when he ventures into more contemporary territory,

attacking with polemic zeal what he sees as confused critical assaults

on modern poetry: the belief in a “vague past the nostalgists can

never quite pinpoint” when poetry could still unite everyone, or in a

“capacity to transcend history” that often seems to rely on its poetic

purveyors being “white men of a certain class”. The hatred of poetry, Mr

Lerner shows, can suddenly and revealingly become a vehicle for bitter

politics. Yet he also sees communal redemption in the strange bond people

have with this ancient art form: if we constantly think poetry is an embarrassing

failure, then that means that we still, somewhere, have faith that it

can succeed.

http://tanvien.net/new_daily_poetry/9.html

MIRRORS AT 4 A.M.

You must come to them sideways

In rooms webbed in shadow,

Sneak a view of their emptiness

Without them catching

A glimpse of you in return.

The secret is,

Even the empty bed is a burden to them,

A pretense.

They are more themselves keeping

The company of a blank wall,

The company of time and eternity

Which, begging your pardon,

Cast no image

As they admire themselves in the mirror,

While you stand to the side

Pulling a hanky out

To wipe your brow surreptitiously.

Charles Simic: Sixty

Poems

Gương, 4 giờ sáng

Bạn phải rón rén,

me mé, tới đó (1)

Những căn phòng, đầy mạng nhện, trong bóng

tối.

Lén nhìn 1 cú, cái vẻ trống

trơn của chúng

Đừng để chúng lén "đợp" lại bạn

Cũng 1 cú!

Niềm bí ẩn là,

Ngay cả cái giường trống trơn

Thì cũng là 1 gánh nặng cho chúng.

Một cái cớ.

Chúng thấy bình yên hơn

Cảm thấy chúng là chúng hơn

Khi có bạn quí cận kề

Là bức tường trần trụi

Là thời gian

Là vĩnh cửu

Những thứ đó, xin lỗi

bạn

Chúng đếch để bóng của chúng

Trên mặt gương

Khi chúng tự sướng

Trong lúc bạn đứng né

qua 1 bên

Rút chiếc khăn tay

Kín đáo lau lông mày

1.

with one side faced forward

<I had to walk sideways to

get between the two towering piles of boxes>

Synonyms broadside, crabwise,

edgeways [chiefly British] [net]

Chữ này - sideways -

của tiếng anh hay quá, tiếng việt không có từ tương đương

. Nó vừa có nghĩa là không đi thẳng đến

trước mặt, chỉ đi bên mé, bên rìa, hoặc

đi bằng ngõ vòng vo, lại vừa có nghĩa len lén

.

K

Note: Bài thơ này, mới thấy trên Gió-O.

Nhớ là, không làm sao dịch được từ

"sideways", bèn cầu cứu K.

Tks again.

Bản của Lý Ốc, theo Gấu, dịch ẩu quá, "as

always": "to them" sao mà là "đến bên cạnh chúng";

nếu đã "lén" lau chân mày,

thì cắt bỏ "một cách kín đáo"!

Thảo nào, ngay cả thi sĩ mà cũng thù

ghét thơ!

Why?

Poets

and non-poets alike hate poetry, he argues, because poetry will

always fail to deliver on the transcendental demands people have invested

in it. As a result they enjoy pronouncing upon the abstract powers and

possibilities of poetry more than they actually like to sit down and

read it. As Keats wrote in “Ode on a Grecian Urn”, “Heard melodies are

sweet, but those unheard/Are sweeter.” Mr Lerner takes his cue from

Keats, but is a little more frank when he describes “the fatal problem

with poetry: poems”.

Đọc thơ tán gái/thơ

ngồi bên ly cà phê nhớ bạn hiền thì thật là

ngọt ngào/ Nhưng đếch đọc chúng, ngọt hơn nhiều!

Thơ luôn thất bại, không đáp trả những

đòi hỏi siêu thoát mà người đọc đầu tư

vào nó

Cái vấn nạn tàn khốc của thơ, chính

là: những bài thơ!

http://www.gio-o.com/LyOcBR/LyOcBRTamGuongDich.htm

Những Tấm Gương Lúc 4 AM

Em hãy đi nép đến bên

cạnh chúng

Những căn phòng trong in bóng sọc giăng,

Len lén nhìn vào cõi không

gian trống trơn

Đừng để chúng bắt dính

Một ánh liếc nhìn của em dội lại.

Bí mật là,

Ngay cả chiếc giuờng trống cũng mang gánh nặng,

Một sự giả vờ.

Chúng vẫn còn đang tự gắn liền

Sự kết liên với bức tường phẳng tắp,

Mối thân quen cùng với thời gian và

muôn năm

Mà, xin em,

Hãy lánh mặt

Khi chúng tự ái mộ mình trong gương;

Trong khi em đứng nép bên

cạnh

Lấy ra chiếc khăn tay

Em lén lau nét chân mày một

cách kín đáo.

Đọc/Viết

mỗi ngày

Trăng ơi

thơ ấu mãi

Note: Bài viết này,

về tập truyện ngắn của 1 bạn văn - có thể là do 1 đấng phi

công VC vừa đi xa, lại được 1 bạn văn khác, NND, trích

& post một mẩu trên FB - khiến thiên hạ xôn xao.

Nay post lại toàn thể.

Nó liên can đến 1 cô bé, và

Hà Nội của cô bé đó, cả hai thì đều

đã mất.

Hà Nội Của Gấu

Gấu, Bắc Kỳ 54. Rời Hà Nội khi

vừa mới biết yêu cái cột đèn, cái ngã

tư, tiếng còi mười giờ chạy trên thành phố... Vào

Nam, Gấu nhớ tiếng còi, nhớ cái tháp rùa đến

ngơ ngẩn mụ cả người, bèn tự nhủ thầm, phải kiếm cho được một cô

bé Hà Nội...

Cô là em của một người bạn học. Ông anh vợ

hụt học dưới Gấu một lớp. Quen qua một người bạn, tên Uyển, hồi

ở hẻm Đội Có, Phú Nhuận.

Kỷ niệm lần đầu tới nhà cô bé, nghĩ lại thấy

thật buồn cười.

Ông anh cô khi đó đang học Đệ Tam, ban toán,

và ông đã ra câu đố: muốn gặp em tao thì

phải giải cho được bài toán hình học này.

Chẳng hiểu ông thực tình bí, hay là muốn

thử tài, theo kiểu: mày có đủ sức chinh phục con

em tao hay không? Hồi đi học, Gấu vốn nổi tiếng là một cây

toán. Cô em cũng dân toán, sau học y khoa.

Lên đại học, ghi danh chứng chỉ Toán Đại Cương;

tới kỳ thi, không hiểu bài toán muốn gì,

Gấu nộp giấy trắng ra về!

Nhà nghèo, Gấu chỉ đủ tiền mua cours của giáo

sư Monavon, mà không hề làm một bài tập nào.

Ôi, giấc mộng đã tan mà sao ảo tưởng vẫn

còn!

Khi Gấu quen, cô bé mới mười một tuổi, chưa có

núm cau. Chưa có gì, chỉ có một nỗi buồn

Hà Nội, ở trong đôi mắt thăm thẳm.

Như lạnh lùng tra hỏi: anh yêu tôi hay là

anh yêu Hà Nội?

Vừa ra ý ỡm ờ: anh yêu tôi, vì tôi

độc?

Và đẹp?

Nhà cô bé giầu, Gấu sững sờ tự hỏi, tại sao

lại có nỗi buồn như thế ở trong cô bé mới mười một

tuổi?

Sau này thân rồi, cô tâm sự: đi học,

H. chỉ có mỗi một cái áo dài trắng độc nhất.

Có lần, H. nghe mấy con bạn nói đằng sau lưng: con nhỏ

này nó làm bộ nghèo...

Lần cuối cùng gặp cô bé, khi mối tình

đã tan vỡ. Cô lúc này coi Gấu như một người

thân, nói: H. mới đi chợ cho mẹ, lỡ tiêu quá

một chút, anh đưa H. để bù vô. H. rất ghét

phải giải thích...

Em gái của cô, mỗi lần thấy bố vô phòng,

là bỏ ra ngoài.

Lần cuối cùng hẹn gặp trước khi Gấu lấy vợ: cô đang

học y khoa, ở tít mãi trong Chợ Lớn. Chỗ gặp mặt là

một quán Tầu ngay Chợ Đũi. Gấu vẫn thường ngồi đó, chờ

cô bé đưa em đi học tại một trường kế bên, rồi ghé.

Cô em gái có lần thấy, đang bữa ăn chiều như nhớ

ra, kêu "chị, chị ra đây em nói cái này

hay lắm: buổi sáng em thấy chị đi với anh Gấu."

Bạn bè, cô, và cô em gái vẫn

gọi anh bằng cái tên đó. "Có thể bữa nào

giận H. nó sẽ nói cho cả nhà nghe, nhưng cũng chẳng

sao..."; Gấu ngồi chờ, cố nhớ lại những kỷ niệm cũ. Khi quá giờ

hẹn 5 phút, anh bỏ đi.

Sau này, anh nghe cô kể lại: Bữa đó, trời

mưa lớn, H. đội mưa chạy xe từ Đại học Y khoa, suốt quãng đường

Chợ Lớn - Sài Gòn. Cũng biết là vô ích,

vô phương. Lũ bạn nói, con này điên rồi. Tới nơi,

đã trễ hẹn. Thường, em vẫn trễ hẹn, anh vẫn chờ (có lần anh

nói anh có cả một đời để chờ...), nhưng lần đó, em

hiểu.

Bữa đó, mưa lớn thật. Gấu đội mưa đi ra khỏi quán.

Đi khơi khơi, không chủ đích, mơ hồ hy vọng những đợt mưa

xối xả trên thành phố Sài Gòn xóa

sạch giùm tất cả những kỷ niệm về một cô gái

Hà Nội,

độc,

và

đẹp...

Độc, là chuyện sau này, do Gấu tưởng tượng ra,

khi đi tìm một cái tên, cho một cuộc chiến.

Sự thực, những kỷ niệm về một miền đất, về một thành phố,

và về cô bé, chúng thật đẹp.

*****

"Suốt khoảng phố gần trường toàn nhà một tầng cửa

gỗ lùa, lọt vào một nhà cửa sổ chấn song sắt luôn

mở rộng. Có một lồng chim ngày nào đi học tôi

cũng thấy treo phía ngoài. Chim gì chẳng đẹp. Trông

như mớ cỏ rối. Nhưng tiếng hót thì trong veo. Trong. Và

phấp phỏng như nắng thu đang do dự rây qua ngàn vạn lá

xuống phố. Nhà ấy không bán hàng. Có

những đứa trẻ ăn mặc đẹp hơn tôi, chân đi dép nhựa

ra vào. Chúng đến đó học đàn. Chúng

làm tôi tủi thân nhiều hơn là thẹn. Có

một lần tôi bị tụt quai dép cao su và tôi chẳng

còn cách nào hơn là lếch thếch xách

cả dép lẫn cặp nhón nhén đi bộ trên hè

phố trước mặt chúng nó.

Từ ngôi nhà chúng ra vào bay ra những

hợp âm thô kệch, lập cập. Thua tiếng hót của con

chim giống như nùi cỏ rối (....) Nhưng không hiểu sao tôi

cứ buồn buồn khi nghe tiếng dương cầm vang lên lập cà lập

cập dưới ngón tay bọn trẻ con không quen biết..."

"Có lần tôi nhìn thấy cô chơi đàn.

Tôi không biết đó là bản gì. Nhưng tiếng

pi-a-nô buổi tối thành phố lên đèn ấy tôi

nhớ lập tức. Tiếng đàn mới cao sang làm sao. Trong vắt.

Róc rách. Dường như những thân sao đen cao vút

đang từ từ vướn lên, vòm lá mở ra để lộ một bầu trời

đen thẫm, mịn màng như một đĩa thạch và chi chít

sao."

"Chiến tranh đánh phá lần thứ hai. Có vẻ

ác liệt hơn lần trước. Cũng có thể là vì

tôi lớn hơn và biết sợ nhiều hơn trước. Chúng tôi

lại đi sơ tán. Để lại Hà Nội những hầm công cộng dài

rộng mênh mông, những hố tăng xê ngập nước ngày

mưa. Để lại tiếng loa truyền thanh và tiếng còi báo

động nghe hết hồn hết vía rú lên từ phía Nhà

Hát Lớn..."

".... Hồi ức chiến tranh thường chỉ quẫy cựa khi đi qua Phố Huế.

Một đứa lớp tôi chết ở đó. Vệt bom liếm hết nhà

nó thì dừng và hôm đó là hôm

nó về lấy gạo nuôi em."

(Những giọt trầm, truyện ngắn Lê Minh Hà)

Gấu được đi học Hà Nội, là nhờ bà cô

lấy chồng Pháp. Một kỹ sư Sở Hỏa Xa Đông Dương. Bà

cô đẹp, cao, sang, không một chút liên can tới

cái làng nghèo đói ven đê sông

Hồng. Người ở đó không muốn bà về. Chỉ cần tháng

tháng gửi tiền. Vì cũng là một người cùng làng,

thằng cháu bị vạ lây, thời gian đầu sống với bà cô.

Có thể, lúc đầu bà cô chỉ nghĩ tới

Gấu, do tội nghiệp. Chẳng bao giờ bà hỏi han. Gấu cũng chẳng dám

đòi hỏi gì, ngoài hai bữa cơm, rồi lo đi học. Bà

cho Gấu ở riêng một căn phòng kế bên nhà bếp.

Không được bén mảng lên nhà trên.

Gấu chỉ có một bộ quần áo đi học. Mỗi lần giặt,

ủi liền, cho kịp giờ đi học. Có những lần quá ướt, bàn

ủi không kịp nóng. Cho tới một bữa, Gấu ỷ y, chạy ra ngoài,

khi ngửi mùi khét thì đã xong một bên

ống quần.

Đó là một villa trông ra hồ Halais. Nhà

của hai ông Tây, đều kỹ sư Sở Hỏa Xa Đông Dương.

Ông Tây già, là chồng bà cô.

Chức vụ chắc thua ông Tây trẻ, vì ông này

có tới hai người hầu: một người bếp, một người bồi. Ông

Tây già ăn uống đều do bà vợ. Ông bếp già,

vào những ngày cuối tuần, chủ đi chơi, thường dắt gái

về nằm trong bóng tối hành lang phía trước. Mỗi

lần như vậy, Gấu lén lên nhà trên, bò

tới sát, chỉ cách bức tường, cánh cửa, rồi hồi hộp

lắng nghe. Một lần cô gái làng chơi biết, nói:

có người ở bên trong nhà. Ông bếp hừ, hai thằng

bé, trời tối mịt, chúng nó chẳng thấy gì đâu.

Mỵ là tên anh bồi. Gấu không nhớ tên

ông bếp già. Ông rất thù ghét Tây,

tuy làm bồi bếp. Gấu biết từng chi tiết chiến thắng Điện Biên

Phủ, là do ông kể. Chắc cũng chỉ từ trí tưởng tượng

của ông. Hiệp định Genève chia đôi đất nước, ông

về làng, chắc chắn là khổ sở với quá khứ Việt gian.

Gấu gặp cả hai vợ chồng anh Mỵ, và đứa con gái duy nhất mới

sinh được vài tháng, ở Hải Phòng, những ngày

chờ đợi tầu. Thằng em đã về quê, ở với bà vợ lớn.

Lần đó, anh Mỵ nói với bà cô. Bữa

hôm sau, bà dẫn Gấu đi mua mấy bộ quần áo. Bà

mắng: tại sao không nói. Thấy thằng cháu im thin

thít, bà như hiểu ra, giải thích: Tao chỉ ghét

mẹ mày. Cả làng cả họ cứ xúm vào gấu váy

con mụ me Tây này.

Không những mắng, mà còn tát

cho Gấu vài cái.

Đó là lần bà bắt gặp hai đứa, Gấu, thằng

Hìu, em anh Mỵ, trời tối thui mà cũng cố căng mắt nhìn

ra phía ngoài...

Lếch thếch xách dép, một kỷ niệm như vậy

dù sao cũng dễ thương hơn nhiều, so với của Gấu, những ngày

đầu học Nguyễn Trãi, với cái quần độc nhất, với đôi

guốc lạch cạch nện trên đường phố, trong sân trường. Nhưng

dù dép, dù guốc, cũng không bằng chân

trần, lúc tan học, nhìn lũ bạn đứng từ ngoài liệng

cả dép lẫn cặp vào tới tận gậm giường bên trong nhà,

rồi theo nhau chạy ra bãi cát dưới chân cầu sông

Hồng, hoặc lang thang bên dưới vòm trời thành phố.

Và tiếng còi dễ thương đuổi theo Gấu suốt đời chưa biến

thành ghê rợn, nhưng tiếng kèn đồng thê thảm

từ một vũ trường gần bờ Hồ theo Gấu mãi, cùng với hình

ảnh cô gái bán rau muống bị Tây hiếp đứng co

ro cố túm chiếc quần còn rỉ dòng nước nhờn, khi nhìn

thấy thằng nhỏ đi học đang bước tới, ngay gần nhà ở ngoại ô

Bạch Mai, kế bên đường rầy xe điện.

"Vậy mà không hiểu sao đôi khi tôi

cứ nghẹn ngào, không làm sao dứt đứt ra khỏi lòng

dạ những xôn xao của cái thời ngốc".

(Lê Minh Hà, Những giọt trầm)

Ngay khi từ biệt, Gấu đã biết, sẽ có ngày

cô bé (Hà-nội?) trở lại, qua một hình

bóng khác. Khó mà dứt đứt ra khỏi lòng

dạ, một thành phố, một đoạn đời.

Sự thực, khi gặp ông anh vợ hụt lần đầu, Gấu không

hề biết, ông có một người em gái, tên là

"cô bé". Nhưng chuyện ông đưa ra bài toán

đố là có thiệt. Về già nghĩ lại, bao chuyện may

rủi trên đời, đều là do chuyện mê toán của

Gấu, kể từ khi còn ở Hà Nội. Người đầu tiên khám

phá ra tài làm toán của Gấu là Ông

Tây, chồng bà cô.

Bà cô Gấu, tuy bề ngoài lạnh lùng,

nhưng lúc nào cũng để ý đến Gấu, qua... Ông

Tây. Một lần bà nói, “Ông Tây bảo, mày

còn ngu hơn thằng Hìu, em anh Mỹ”.

Đó là một buổi chiều, Ông Tây

đi làm về. Có bà cô ngồi trên xe. Khi

xe làm hiệu rẽ vào cổng, thằng cháu nhanh nhẩu

tập làm bồi, mở vội hai cánh cổng bằng sắt. Thằng Hìu

đứng bên, dơ tay chặn lại. Không hiểu làm sao nó

biết, hai người chỉ đậu xe, về nhà thay đồ, và còn

đi shopping.

Lần thứ nhì đụng độ Ông Tây, là

bữa Gấu mê mải làm toán, ngay hàng lang trước

villa. Dùng phấn trắng vẽ ngay trên mặt gạch. Gấu không

nghe thấy tiếng xe, tiếng mở cổng, ngay cả khi Ông Tây tới

sát bên Gấu… chỉ tới khi ông hừ một tiếng rất ư là

hài lòng, và sau đó bỏ vào trong nhà.

Chắc ông đã mê mải theo dõi, và hồi hộp,

không hiểu thằng bé nhà quê này có

chứng minh nổi bài toán hình học hay không.

Ông là kỹ sư, và hình ảnh thằng nhỏ đang say

sưa với bài toán đến nỗi quên phận sự làm bồi,

không mở cổng cho ông, có thể làm ông nhớ

lại thằng nhỏ-là ông ngày nào.

Bữa sau, bà cô mặt mày tươi tỉnh cải chính

câu nói bữa trước, “Không, Ông Tây nói,

mày thông minh hơn thằng Hìu.”

Chính Ông Tây mới là người quyết định

tương lai của Gấu. Bởi vì bà cô, kể từ đó,

đã có ý định cố lo cho thằng cháu ăn học.

Trong quyết định bỏ vào Nam của Gấu, có giấc mơ

học giỏi tiếng Pháp, để viết một bức thư cám ơn một ông

tây thuộc địa.

My Old Saigon

V/v SN của AA

Late at night. Monday. The

twenty-third.

The capital's outlines in the

mists.

Some idiot's given us the word,

He's informed the world that

love exists.

And out of boredom or laziness

Everyone believes and lives that

way:

They all look forward to trysts,

no less,

They sing their love songs night

and day.

But to some, the secret's revealed,

The smallest silence weighs like

a brick.

I too stumbled on what was concealed.

Since then I've felt as if I

was sick.

1917

Đêm khuya, muộn. Thứ Hai. Ngày 23

Những đường ven thủ đô, trong sương mù

Một tên ngu ngốc nào đó, phán

Rằng tình yêu vưỡn còn!

Yêu hiện hữu!

Và do chán quá, nản quá, và… lười

quá

Chúng ta bèn OK, OK!

Và mọi người bèn sống theo kiểu này:

Tất cả bèn mong ngóng, hẹn hò

Hát hò, ngày và đêm

Những bài tình ca của chúng ta!

Nhưng với vài người, bí mật bật mí

Một sự im lặng, dù nhỏ nhoi cỡ nào

Thì cũng nặng như đá

Gấu, cũng té nhào khi vấp vào điều được che giấu

Kể từ đó, lúc nào Gấu cũng cảm thấy bịnh!

AA viết về St. Petersburg làm

GCC nhớ Sài Gòn của Gấu.

Gấu cũng có 1 Saigon của Dos, và cũng đã từng

viết về nó, về những lần đọc Dos trong 1 quán cà

phê hủ tíu Tầu, trong khi chờ BHD.

Mùi cà phê, thì là mùi

cà phê túi, và thay vì cà phê

cháy, thì là mùi 1 ly hồng trà.

The City

THE WORLD

OF ART artists had a sense of Petersburg's "beauty" and it was they,

incidentally, who discovered mahogany furniture." I remember Petersburg

from very early on-beginning with the 1890s. It was essentially Dostoevsky's

Petersburg. It was Petersburg before streetcars, rumbling and clanking

horse-drawn trams, boats, signs plastered from top to bottom, unmercifully

hiding the buildings' lines. I took it in particularly freshly and keenly

after the quiet and fragrance of Tsarskoe Selo. Inside the arcade there

were clouds of pigeons and large icons in golden frames with lamps that

were never extinguished in the corner recesses of the passageways. The

Neva was covered with boats. A lot of foreign conversation on the street.

Many of the houses were painted red (like the Winter Palace), crimson,

and rose. There weren't any of these beige and gray colors that now

run together so depressingly with the frosty steam or the Leningrad twilight.

There were still a lot of magnificent wooden buildings then (the houses

of the nobility) on Kamennoostrovsky Prospect and around Tsarskoe Selo

Station. They were torn down for firewood in 1919. Even better were the

eighteenth-century two-story houses, some of which had been designed by

great architects. "They met a cruel fate"-they were renovated in the 1920s.

On the other hand, there was almost no greenery in Petersburg of the 1890s.

When my mother came to visit me for the last time in 1927, she, along with

her reminiscences of the People's Will, unconsciously recalled Petersburg

not of the 1890s, but of the 1870s (her youth), and she couldn't get over

the amount of greenery. And that was only the beginning! In the nineteenth

century there was nothing but granite and water.

More about the City

YOU CAN'T

BELIEVE YOUR eyes when you read that Petersburg staircases always smelled

of burnt coffee. There would often be tall mirrors and sometimes carpets.

But not in one single Petersburg home did one ever smell anything on

the staircase but the perfume of the ladies who had passed through and

the cigars of the gentlemen who had passed through. The fellow probably

had in mind the so-called "black" entrance (that is the back entrance,

nowadays, generally, the only one) and there it really could smell of

anything at all, because the doors from all the kitchens opened out onto

that stairway. For example, bliny for Shrovetide, mushrooms and fast-day

oil during Lent, and smelt from the Neva in May. When they were cooking

something pungent, the cooks would open the door onto the back staircase

"to let out the fumes" (that's how they termed it), but nevertheless, the

back staircase, alas, more often than not smelled of cats. The sounds in

the Petersburg courtyards. First of all, the sound of firewood being thrown

into the cellar. Organ-grinders ("Sing, my little sparrow, sing, soothe

my heart ... "), grinders ("I grind knives, scissors ... "), secondhand-clothes

dealers ("Dressing gowns, dressing gowns ... "), who were always Tatars.

Tinsmiths. "I've got Vyborg pretzels." The reverberation in the courtyards

and wells.

Smoke over the rooftops. The Petersburg Dutch ovens. The Petersburg

fireplaces-an ineffective offensive. The Petersburg fires during bitter

frosts. The peal of bells that would deafen the city with their sound.

The drum roll that always made one think of an execution. The sleds that

collided with all their might against the curbstones of the humpbacked bridges,

which now have nearly lost their humpbackedness. The last branch-line on

the islands always reminded me of a Japanese print. The horse's muzzle,

frozen with icicles, almost touching your shoulder. And then there was the

smell of damp leather in the horse-drawn cab when it rained. I composed

almost all of Rosary in conditions like these, and at home would merely write

down the finished poems.

Cùng với những cuộc phiêu

lưu của những tác phẩm lớn ở trong tôi, Sài-gòn

trở thành một sân khấu cho tôi đóng vai những

nhân vật-nhà văn. Thành phố thân yêu,

một buổi sáng đẹp trời bỗng nhường cho một St. Petersbourg thời

Dostoievsky với những cầu thang âm u, và cậu sinh viên,

trong một góc bàn tại một tiệm cà phê Tầu nơi

Ngã Sáu, một mình đi lại trong giấc mơ vĩ đại, biến

đổi thế giới, làm lại loài người.

Hay một London của Dickens, một buổi

chiều đầy sương mù, chú bé Oliver Twist đói

lả người, như tôi, một ngày trong chuỗi ngày cắp

sách đến trường, đêm đêm làm bồi bàn,

thời người Mỹ chưa đổ quân ào ạt vào Việt Nam. Thành

phố chưa có xa lộ, chưa có cầu Sài-gòn. Và

tiệm chả cá Thăng-Long nơi tôi tối tối bưng xoong mỡ sôi

đổ lên dĩa chả cá, nghe tiếng mỡ kêu xèo xèo,

chưa biến thành nhà hàng Kontiki ở ngay đầu đường

Phạm Đăng Hưng, nơi dành riêng cho đám quân

nhân Hoa Kỳ.

Ngày mai trời sẽ mưa trên

thành phố Bouville

Demain il pleuvra sur Bouville

(Sartre, La Nausée)

Ôi Sài-gòn, một

Sài-gòn hư tưởng, một Bouville, một London, của riêng

tôi đó!

|

Trang NQT

art2all.net

Lô

cốt

trên

đê

làng

Thanh Trì,

Sơn Tây

|

|