|

|

Viết Mỗi Ngày

Mà không phải chỉ có Dương Thu Hương. Lớn hơn Dương Thu Hương rất nhiều,

nhà văn Alexander Solzhenitsyn, giải Nobel văn chương năm 1970, bị trục

xuất khỏi Nga vào năm 1974; và sau một thời gian ngắn sống ở Tây Đức và

Thụy Sĩ, ông được mời sang Mỹ. Ông định cư ở Mỹ cho đến năm 1994, khi

chế độ cộng sản đã sụp đổ tại Nga, ông mới về nước. Trong gần 20 năm ở

Mỹ, Solzhenitsyn chỉ sống một cách lặng lẽ ở một địa phương khuất lánh

heo hút. Trừ sự ồn ã ở vài năm đầu, sau đó, dường như người ta quên mất

ông, hơn nữa, có khi còn bực bội vì ông. Một số quan điểm của ông, lúc

còn nằm trong nhà tù Xô Viết, được xem là dũng cảm; lúc đã sống ở Mỹ,

ngược lại, lại bị xem là cực đoan.

NHQ

Solz qua Tây Phương sau bài diễn văn để đời ở Harvard, [chửi

Mẽo như điên], ông lui về pháo đài của ông,

ở Vermont cả gia đình xúm nhau làm nhà xb, viết

như điên, in như điên. Không thèm vô quốc

tịch Mẽo, phán, ngay từ lúc mới ra hải ngoại, tao sẽ về, và

lúc đó chế độ Đỏ đã sụp rồi [nhân tiện, bài

viết mới nhất của Bùi Văn Phú là hàm ý

này, lưu vong sẽ có ngày trở về, và Vẹm lúc

đó đã chết].

Đúng là điếc không sợ súng.

1 YEAR AGO TODAY Sat, Oct 4, 2014 Chữ người tử tù

Nhà văn Isaac Bashevis Singer, khi phải lựa chọn một số truyện ngắn,

để làm một tuyển tập, ông nói đùa, mình đúng là một đấng "quân vương",

với ba ngàn cung tần mỹ nữ, và hàng lô con cháu. Chẳng muốn bỏ đứa nào!

Ông sinh năm 1904, tại Ba Lan, di cư sang Mỹ năm 1935, và một thời

gian làm ký giả cho tờ báo cộng đồng Jewish Daily Forward, tại New York

City. Chỉ viết văn bằng tiếng Iddish, và được coi như nhà văn cuối cùng,

và có lẽ vĩ đại nhất của "trường" văn...

Continue Reading

Follow

1 hr · Edited ·

Mấy

hôm anh Tường cứ đòi ra Huế chơi, cái Líp con

gái anh bận lắm nhưng vẫn cố sắp xếp đưa ba mạ ra Huế. Ra Huế được

ba ngày, thăm bạn bè đầy đủ xong đột nhiên anh đổ bệnh

thập tử nhất sinh. Sự sống tính từng giờ. Cái Líp khóc

quá, nó làm bài thơ:" Xin ba vài năm nữa"

rất cảm động, anh Tô Nhuận Vĩ nói ai đọc bài thơ cũng

ứa nước mắt. Có lẽ anh Tường cảm động quá nên làm

theo ý con. Từ sáng nay anh đã khá lên

phần nào, tuy vẫn nằm thở ô xy.

P/S: Anh Tường đang ốm đau,

kẻ nào chĩa mồm vào đây biêu riếu anh ấy sẽ bị

coi là quân mất dạy và sẽ bị chặn ngay lập tức.

*****

Sợ lâu lắm mới đi được.

Cầu được như Võ Tướng Quân!

GCC

Tribute to Võ Phiến

Võ Phiến, nhà văn Bình Định

Trường hợp Võ Phiến

Note: Ông con đấu tố ông bố.

Khi

viết những dòng này mình vẫn không tin nhà

văn Nhật Tuấn đã rũ bỏ "Nơi Hoang Dã" đi về cõi khác!

Nhớ lần về Việt Nam nhà văn Nhật Tuấn chỉ đường cho mình tới nhà anh ở

Bình Dương. Đang lớ ngớ hỏi đường thấy anh ấy đi xe máy ra trên xe treo

lủng lẳng 4 con gà chết. Anh nói: chó nhà mình nó cắn mấy con này. Em

có biết làm thịt gà không? Mình trả lời em biết, nhưng em và bạn em thêm

anh nữa làm sao ăn hết cả 4 con.

- Để mình đưa cho ông hàng xóm 2 con nhờ ông ấy vặt lông. Ba

người 2 con, lại còn nhiều đồ mồi tớ mua rồi, ăn không hết đâu. À mà

sao Tuấn sống ở nước ngoài bao nhiêu năm rồi mà gầy thế? Thế thì anh

phải hỏi "nước ngoài", em cũng chịu, mình trả lời.

Thấy anh sống một mình nhà đất thì rộng mình nói: ở một mình thế này,

nhớ có chuyện gì thì sao, khi trái gió trở trời? Anh Nhật Tuấn nói:

không sao đâu, tớ quen rồi. Tối hôm trước mình uống nhiều nên

nhức đầu. Anh Nhật Tuấn bảo: cậu vào phòng tớ mà nghỉ, tớ ngồi tiếp bạn

cậu, rồi nấu nướng sau. Vào phòng mình cũng không ngủ được cứ nhớ về

tiểu thuyết "Đi Về Nơi Hoang Dã" của anh Nhật Tuấn mà người gửi cho mình

là anh ruột anh ấy, nhà văn Nhật Tiến (hiện định cư tại California -

Mỹ.)

Xuống bếp, mình làm 2 món gà xé phay

và om sả ớt, xào mực, nấu canh chua cá lóc...

Uống bia xanh cổ rụt Sài Gòn là chính, ăn chỉ là...gia vị. Bao nhiêu

là chuyện để nói. Trong câu chuyện có nhắc tới nhân vật Beo Hồng... mình

nói: thôi anh, nhắc làm gì, chua cả miệng. Anh em mình có bao nhiêu

chuyện để nói...

Cách đây chưa lâu, anh còn nhắn vào FB

của mình: có thời gian về nhậu với tớ đi...

Thế mà!

Lúc này đây mình cứ day dứt, băn khoăn câu hỏi: anh sống một mình,

trước lúc anh rời bỏ "Miền Hoang Dã" có ai bên cạnh anh không?

Tạm biệt anh.

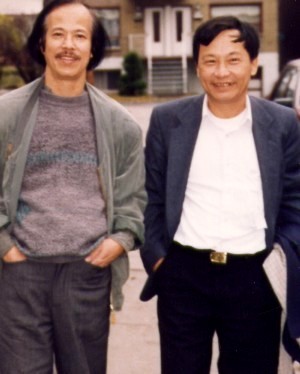

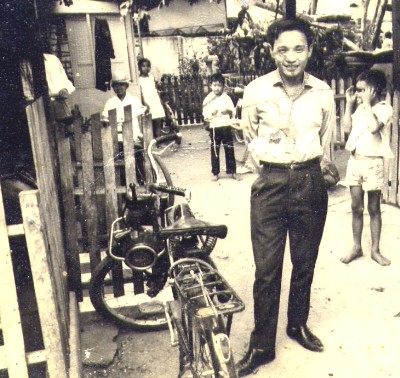

(Praha - 6 -10 - 2015) (Ảnh mình chụp với nhà văn Nhật Tuấn tại nhà anh ở Bình Dương cuối năm 2013.). Một số tác phẩm của nhà văn Nhật Tuấn: Trang 17 (1978)

Con chim biết chọn hạt (1981)

Bận rộn (1985)

Mô hình và thực tế (1986)

Lửa lạnh (1987)

Biển bờ (1987)

Tín hiệu của con người (1987)

Đi về nơi hoang dã (1988)

Niềm vui trần thế (1989)

Những mảnh tình đã vỡ (1990)

Tặng phẩm cho em (1995)

Một cái chết thong thả (1995)

RIP

Sếp 1 thời của Gấu Cà Chớn. Gấu đã kể ra rồi, thời gian nhà

xb Văn Học tính tái bản cuốn Mặt Trời Vẫn Mọc, dịch Hemingway.

Anh được Hoàng Lại Giang ra lệnh cùng làm việc với Gấu.

Thời Sự

Nobel Vật Lý

Kajita and McDonald win Nobel physics prize for work on neutrinos

Takaaki Kajita and Arthur McDonald win for discovery of neutrino oscillations, which show that neutrinos have mass

Nobel vật lý về tay hai tác giả khám phá ra những

rung động của neutrios, và điều này chứng tỏ, chúng

có khối lượng!

Ui chao, đúng là THNM, vì bèn nhớ ra câu

tự xoa đầu thần sầu, cái gì gì selfie, Những ngày

ở Xề Gòn.

Note: neutrino, là neutron, tiếng Tẩy, không

phải hạt cơ bản, mà là trung hòa tử, như Gấu còn

nhớ được, nó không có khối lượng. Cái sự kiện

có khối lượng này sẽ gây chấn động trong giới giang hồ

vật lý học.

Một đấng Canada, một đấng Nhật Bổn chia nhau giải Nobel vật lý

Nobel Y học

DESPITE

what the romantic poets would have you believe, the natural world is not

a friendly place. It is full of dangerous creatures, and some of the most

dangerous are the smallest: the bacteria, viruses and parasites that between

them debilitate and kill millions of people every year. But it is possible,

with a bit of cunning, a bit of luck and a lot of hard work, to turn a bit

of nature against itself—to humanity's benefit. And it is for exactly this

sort of work that Sweden's Royal Academy of Sciences has awarded the 2015

Nobel prize in physiology or medicine.

Độc giả Kim Dung hẳn là nhớ câu phán trứ

danh của ông, nơi nào phát sinh độc, thì quanh

quẩn đó, có thứ trị độc.

Giải Nobel Y học năm nay, bảnh hơn, phán, thuốc trị độc, là từ thuốc độc mà ra!

Mặc dù những nhà thơ lãng mạn khiến bạn

tin rằng, thiên nhiên vốn hiền hoà.

Đếch phải như thế.

Nó là nơi đầy những sinh vật nguy hiểm, và một vài

thứ nguy hiểm nhất, thì nhỏ nhất…

Nhưng có thể, với tí

cà chớn, tiếu lâm, láu cá, tí cơ may, và

lao động tới chỉ, con người làm cho thiên nhiên vs thiên

nhiên, để thủ lợi.

Nobel 2015, về diện mạo học hay là y học, được ban cho những con người làm cái thứ việc kể trên.

Cô Rơm và những truyện ngắn khác

Cô Rơm là người Hà-nội. Theo như tôi

biết, hay tưởng tượng rằng mình biết, cô có tên

mộc mạc này, là do bà mẹ sinh ra cô trên

một ổ rơm, khi gia đình chạy khỏi thành phố Hà-nội,

những ngày đầu "Mùa Thu".

Kim Dung cho rằng thiên nhiên khi "bịa đặt" ra một tai ương,

thường cũng bịa đặt ra một phương thuốc chữa trị nó, quanh quẩn đâu

gần bên thảm họa.

Ông kể về một thứ cỏ chỉ có ở một địa phương lạnh khủng khiếp,

và người dân nghèo đã dùng làm giầy

dép.

Những người dân quê miền Bắc chắc không thể quên

những ngày đông khắc nghiệt, và để chống lại nó,

có ổ rơm. Tôi nghĩ Trần Mộng Tú tin rằng "rơm" là

phương thuốc hữu hiệu, không chỉ để chống lại cái lạnh của thiên

nhiên, mà còn của con người.

Ít nhất, chúng ta biết được một điều: tác

giả đã mang nó tới miền Nam, rồi ra hải ngoại, tạo thành

thứ tiếng nói hiền hậu chuyên chở những câu chuyện thần

tiên.

"Ba mươi năm ở Mỹ làm được dăm bài thơ, viết được vài

truyện ngắn. Lập gia đình vốn liếng được ba đứa con (2 trai, 1 gái:

các cháu 22, 20, 19), một căn nhà để ở.... lúc

nào tôi cũng nghĩ tôi là người giầu có lắm....

trong túi luôn có một bài thơ đang làm

dở. Thấy Trời rộng lượng với mình quá. Mấy chục năm trước Trời

có lấy đi nhà cửa người thân. Bây giờ Trời lại

đền bù. Còn quê hương thì lúc nào

cũng thấy ở trong tim, chắc khó mà mất được...".

Nguyễn Quốc Trụ

Cô Rơm và những truyện ngắn khác, nhà xb Văn Nghệ (Cali) 1999.

Nghĩ lại về những bài học quá khứ của Âu Châu

Guardian Weekly, 2 & 8 Oct 2015, đọc Black Earth, Đất Đen: Lò Thiêu như là Lịch sử và như là Cảnh báo, của Snyder

TV sẽ đi bài này. Tác giả bài viết phê

bình cách nhìn của sử gia Snyder, xuất phát từ

những nỗi sợ sinh thái.

Tying the Holocaust to modern-day ecological fears is a flawed premise, says Richard J Evans

Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning by Timothy Snyder

Bodley Head, 480pp

We have got the Holocaust all wrong, says Timothy Snyder, and so we have

failed to learn the lessons we should have drawn from it. When people talk

of learning from the Nazi genocide of some 6 million European Jews during

the second world war, they normally mean that we should mobilize to stop

similar genocides happening in future. But Snyder means something quite different,

and in order to layout his case, he provides an engrossing and often thought-

provoking analysis of Hitler's antisemitic ideology and an intelligently

argued country-by-country survey of its implementation between 1939 and 1945.

Hitler, Snyder correctly observes, was a believer in race

as the fundamental feature of life on Earth. History was a perpetual struggle

for the survival of the fittest race, in which religion, morality and secular

ethics all stood in the way of the drive for supremacy. His political beliefs

reduced humankind to a state of nature, sweeping aside the claims of modern

science to improve the natural world. Interfering in nature, for example

by improving crop yields in order to overcome the food supply deficit in

Germany during the first world war, was wrong: the way to achieve this aim

was to conquer the vast arable lands of eastern Europe.

Race, in Hitler's thought, replaced the state as the most

important characteristic of human society. What he wanted was anarchy, a

virtually stateless society, denuded of rules, laws and ethics, that allowed

the Nazis to do what they had to in the interests of the "Aryan" (ie German)

race. He had already begun to achieve this in Germany itself, where the expanding

world of the stormtroopers, the SS, the camps, the special courts and the

Nazi party was rolling back the frontiers of the established German state

and its institutions well before the war started. But it was only with the

conquest of eastern Europe that Hitler had the opportunity to create a truly

anarchic society in which expropriation, murder and extermination of those

he considered racially inferior - Poles, Ukrainians, Belarusians and other

"Slavs" - could be practiced without restraint.

For Hitler, as Snyder notes, Jews fell into a different

category. They were not a regional nor even a European enemy, but a universal,

global one. Rather than being an inferior race they were a "non -race" or

a "counter-race", not following the laws of nature, as Slavs, Teutons, Latins

and the rest of them did. Hitler's global vision potentially targeted Jews

wherever they could be found.

If the killing fields of eastern Europe could be the site

of mass extermination by virtue of the aboli- tion of the state - the Polish

state, the Soviet state (in the areas conquered by the Nazis), the Estonian,

Latvian and Lithuanian states - then the impact of Nazi exterminism in other

countries depended largely on how far the state and its institutions had

managed to survive. Thus most Jews escaped being murdered in Belgium and

Denmark, where the institutions of the state, headed by the monarchy, remained

largely in place, while in the Nether- lands, where the monarch and the leading

politicians had fled, they did not. Similarly, despite the antisemitism of

the Vichy regime, most French Jews managed to survive the war.

Snyder delivers what is surely the best and most unsparing

analysis of eastern European collaborationism now available, though the preceding

sections on the history of Polish and Russian antisemitism are perhaps longer

and more detailed than was necessary. Overlong, too, are the chapters on

partisan resistance. And although it is better by some distance than Snyder's

previous, overpraised book Bloodlands, Black Earth shares some of the same

failings as that flawed work, delivering an account of the Holocaust that

is skewed far too much towards eastern Europe; it also misunderstands the

ideological roots of the genocide, which, as most historians would now agree,

was set in motion not as an act of revenge against an imagined Jewish world

conspiracy following the failure of Operation Barbarossa in December 1941,

but as an act of hubris launched the previous July, as Hitler and the leading

Nazis considered the operation a resounding success.

This is not a comprehensive history of the Nazi genocide

of the Jews, therefore, but a book with a thesis: and it is here that it

really goes off the rails. In his concluding chapter, Snyder describes the

Holocaust as an act of "ecological panic", the belief of Hitler that the

Jews were "an ecological flaw": nature's harmony could only be restored through

their complete elimination.

In the 21 first century, he speculates, climate change

could lead to wholesale food shortages caused by desertification of huge

areas of the planet, or alternatively drastic economic collapse. The consequences

of the destruction of the state, so obvious in Eastern Europe between the

wars, can now be seen in Iraq and Syria. Territorial conquest and exterminatory

wars might occur with increasing frequency as the condition of the Earth

deteriorates. China might invade Africa. Russia has already invaded Ukraine.

Some Muslims are starting to blame Jews and gays. American evangelical Christians

decry the work of scientists. Climate change, they say, is a myth, de- signed

to give the state greater powers. But this is -just what Hitler said about

the state. Far better, Snyder concludes, to use governments to slow down

and eliminate climate change, reduce its harmful effects and ensure everyone

has enough to eat.

Such proposals seem reasonable enough, but do they really

constitute lessons we should all learn from the Holocaust? Snyder here is

surely confusing Hitler's global crusade against the Jewish "world-enemy"

with his regional agenda of ensuring Germany's food supplies, which the science

of the 1930s was not capable of guaranteeing on the basis of German agricultural

production alone. His speculations about possible Chinese or Russian wars

of conquest driven by the need for resources are wild in the extreme. This

is a pity: much of this book makes for compelling and convincing reading,

but tying historical arguments to ecological nostrums in this way does not

really work.

Bắt Trẻ Đồng Xanh

http://www.diendantheky.net/2010/12/bat-tre-ong-xanh1.html

Note: Bài viết này,

lần đầu đăng trên nhật báo Tiền Tuyến, tờ báo của quân

đội VNCH. Chi tiết này rất quan trọng, đến nỗi Phan Lạc Phúc,

chủ bút, phải đi 1 đường cám ơn.

Có thể nói, khi cho đăng, chọn báo đăng, là VP

đã chấp nhận thái độ chính trị, tôi là

nhà văn chống cộng.

Trong số báo Văn, đặc biệt về VP, có chi tiết này.

Cái dã tâm ăn cướp cho bằng được Miền Nam, có,

từ khi còn ở trong bụng mẹ của từng tên Bắc Kít.

Đẻ ra 1 phát, là ngửi ngay liền cái đói, là bèn nghĩ đến ăn cướp!

Đây là cách giải thích mới nhất về Nazi, của sử gia Snyder, mà TV đang giới thiệu.

Áp dụng vào xứ Mít, quá đúng.

Nhưng cái vụ bắt trẻ này, không đúng.

Đám VC Nam Bộ tự động dâng con nít cho Bắc Kít,

khi bắt con cái của chúng vượt Trường Sơn.

Thế mới dã man.

Cũng như khi được lệnh tập kết, thì tên Nam Bộ nào cũng

còn được lệnh, phải làm cho 1 cô gái Nam Kít

mang bầu, trước khi đi.

“Nature,” he wrote, “knows no political boundaries.”

Thiên nhiên, Hítler phán, đếch biết đến cái

gọi là biên cương chính trị.

Mít vs Lò Thiêu Người

Sách Báo

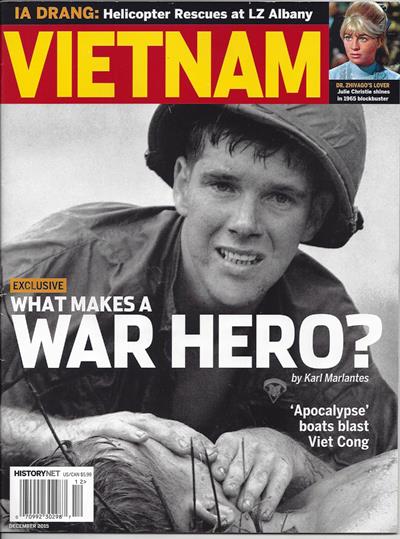

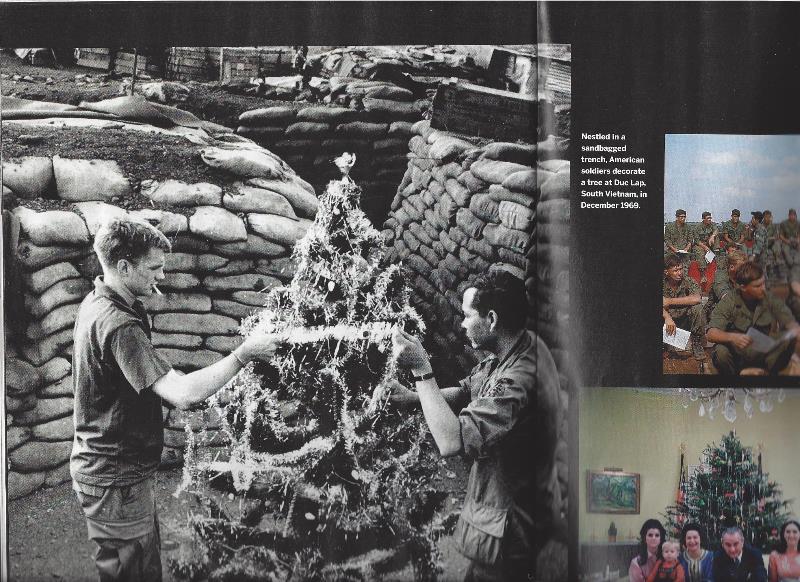

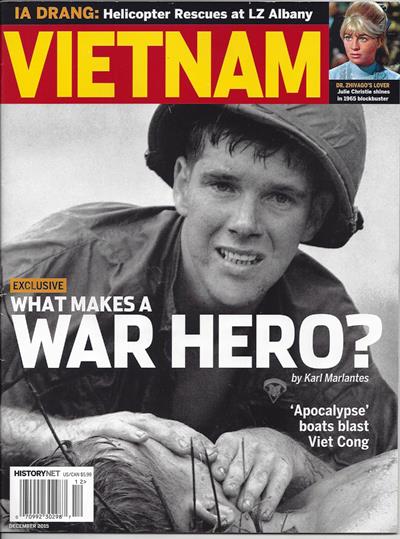

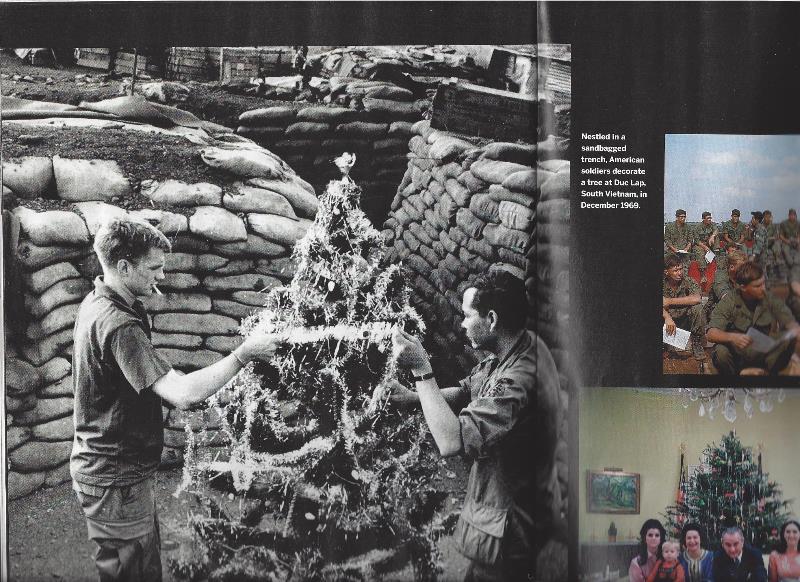

Vietnam, 1965. Noel @ Đức Lập with GI, and “Vĩnh Biệt Tình Em, Dr. Zhivago”, with Julie Christie.

Vẹm chửi Tẩy mũi lõ, chia để trị, khi phân ra Nam Kỳ tự trị, Bắc Kỳ bảo hộ.

Không phải.

Có cái gì đó, khiến Tẩy rất dễ gần với Nam Kít.

Maugham, trong bài viết vế Huế cũng nhận ra.

Chính cái

điều này, càng khiến Bắc Kít, không phải thù

Tẩy mũi lõ, mà thằng em ruột Nam Bộ của nó.

Chán thế!

Cuốn sách những sinh vật tưởng tượng

Viết mỗi ngày

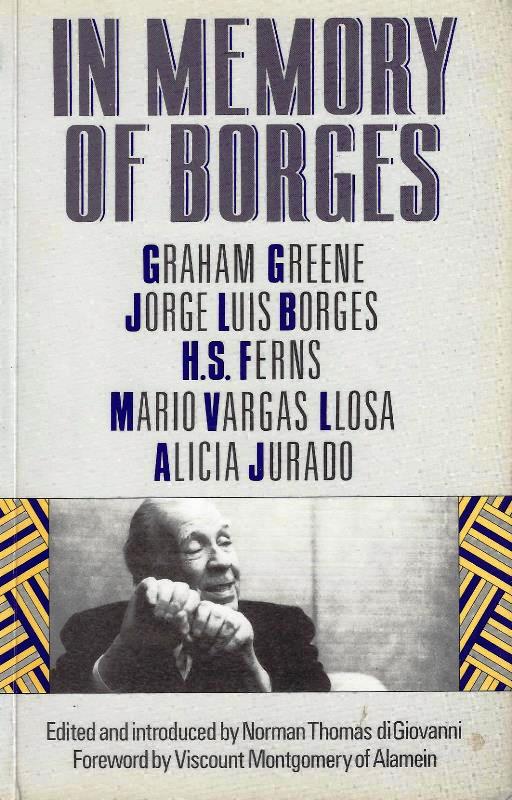

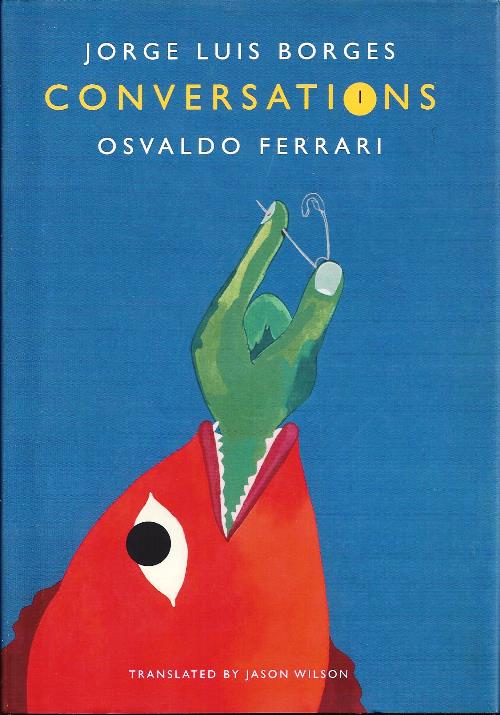

Borges

Conversations

In Memory of Borges

Cô bạn, cô phù dâu ngày nào, Gấu gặp

lại ở hải ngoại. Cô phán, cực kỳ bi thương, cực kỳ hạnh phúc,

tại làm sao mà bao nhiêu năm trời, tình cảm của

anh dành cho tôi vẫn như ngày nào.

Nhờ gặp lại cô, Gấu viết lại được, không chỉ thế, mà còn làm được tí thơ!

Bài viết về cô, Cầm Dương Xanh, được một vị nữ độc giả, Bắc

Kít, Hà Lội, mê quá, bệ ngay về trang FB của cô.

Cô tình cờ thấy trang TV, trong khi lướt net, tìm tài liệu về Camus.

Book of Fantasy

SAIGON 1970 by Charley Seavey - Walking towards the market - Chợ chim chó,

thú, đường Hàm Nghi (đoạn giữa Pasteur và

Công Lý)

Hình manhhai

A Critic at Large October 5, 2015 Issue

The Unforgotten

Patrick Modiano’s mysteries.

By Alexandra Schwartz

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/10/05/the-unforgotten-books-alexandra-schwartz

Levi Page

PRIMO LEVI

Unfinished Business

Sir, please accept my resignation

As of next month,

And, if it seems right, plan on replacing me.

I'm leaving much unfinished work,

Whether out of laziness or actual problems.

I was supposed to tell someone something,

But I no longer know what and to whom: I've forgotten.

I was also supposed to donate something-

A wise word, a gift, a kiss;

I put it offfrom one day to the next. I'm sorry.

I'll do it in the short time that remains.

I'm afraid I've neglected important clients.

I was meant to visit

Distant cities, islands, desert lands;

You'll have to cut them from the program

Or entrust them to my successor.

I was supposed to plant trees and I didn't;

To build myself a house,

Maybe not beautiful, but based on plans.

Mainly, I had in mind

A marvelous book, kind sir,

Which would have revealed many secrets,

Alleviated pains and fears,

Eased doubts, given many

The gift of tears and laughter.

You'll find its outline in my drawer,

Down below, with the unfinished business;

I didn't have the time to write it out, which is a shame,

It would have been a fundamental work.

Translated from the Italian by Jonathan Galassi

PRIMO LEVI* (I9I9-I987) was an Italian chemist and writer, best known for

his memoirs if This Is a Man and The Periodic Table. The poem in this issue

is from Collected Poems, translated by Jonathan

Galassi, from The Complete Works of Primo Levi, edited by Ann Goldstein.

Copyright © I997 by Giulio Einaudi editore s.p.a., Torino.

English translation copyright © 20IS by Jonathan Galassi.

Poetry Magazine Oct 2015

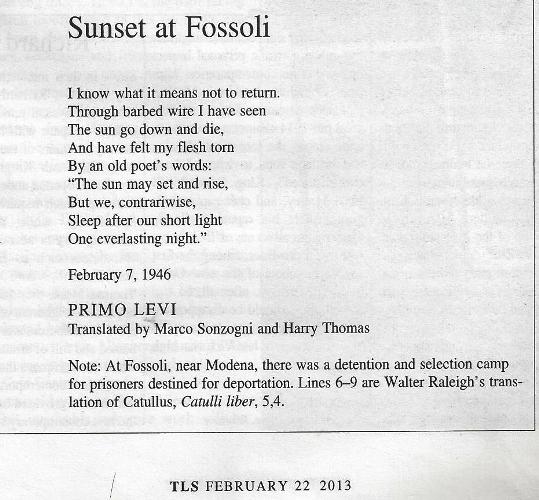

Mặt Trời Lặn

ở Fossoli

Tôi biết, nghĩa là gì,

không trở về.

Qua những

hàng rào kẽm gai

tôi nhìn

thấy

mặt trời xuống và chết

Và da

thịt tôi như bị xé ra

Bởi những

dòng thơ của một thi sĩ già:

“Mặt trời

thì có thể lặn và mọc

Nhưng

chúng tôi, ngược hẳn lại

Ngủ, sau

1 tí ánh sáng ngắn ngủi,

Một đêm

dài ơi là dài”

Tháng Hai,

7, 1946

Primo Levi

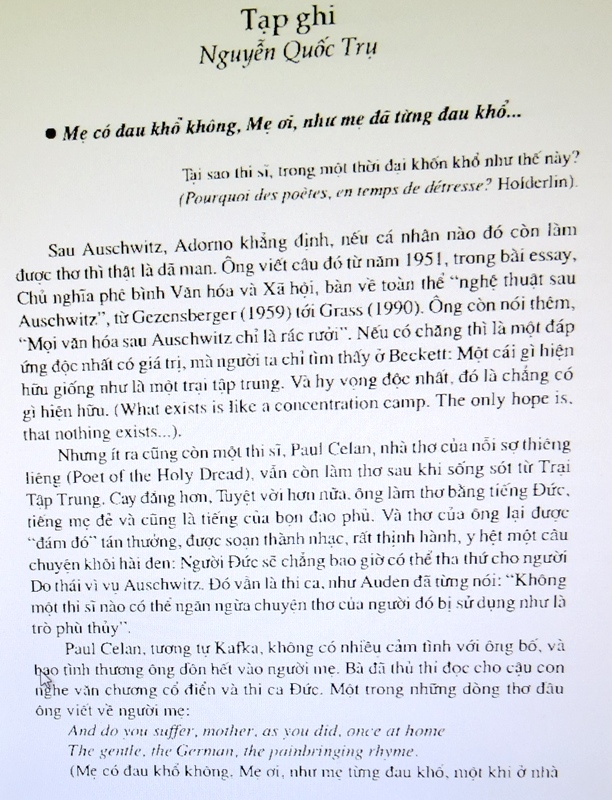

Mít vs Lò Thiêu Người

Tạp Ghi Văn Học, Xuân Đinh Sửu, 1 & 2 1977.

Ngụy có bao giờ nghĩ đến chuyện cải tạo Bắc Kít, nếu thắng trận.

Một trong những

chương của cuốn sách viết về "Sự hung dữ vô dụng". Những chi

tiết về những trò độc ác của đám cai tù, khi

hành hạ tù nhân một cách vô cớ, không

một mục đích, ngoài thú vui nhìn chính

họ đang hành hạ kẻ khác. Sự hung dữ tưởng như vô dụng

đó, cuối cùng cho thấy, không phải hoàn toàn

vô dụng. Nó đưa đến kết luận: Người Do thái không

phải là người. (Kinh nghiệm cay đắng này, nhiều người Việt

chúng ta đã từng cảm nhận, và thường là cảm nhận

ngược lại: Những người CS không giống mình. Ngày đầu

tiên đi trình diện cải tạo, nhiều người sững sờ khi được hỏi,

các người sẽ đối xử như thế nào với "chúng tôi",

nếu các người chiếm được Miền Bắc. Câu hỏi này gần như

không được đặt ra với những người Miền Nam, và nếu được đặt

ra, nó cũng không giống như những người CSBV tưởng tượng. Cá

nhân người viết có một anh bạn người Nam

ở trong quân đội. Anh chỉ mơ, nếu có ngày đó,

thì tha hồ mà nhìn ngắm thiên nhiên, con

người Hà-nội, Miền Bắc. Lẽ dĩ nhiên, đây vẫn chỉ là

những mơ ước, nhận xét hoàn toàn có tính

cách cá nhân.

Cuốn sách những sinh vật tưởng tượng

Viết mỗi ngày

Borges

Conversations

In Memory of Borges

Cô bạn, cô phù dâu ngày nào, Gấu gặp

lại ở hải ngoại. Cô phán, cực kỳ bi thương, cực kỳ hạnh phúc,

tại làm sao mà bao nhiêu năm trời, tình cảm của

anh dành cho tôi vẫn như ngày nào.

Nhờ gặp lại cô, Gấu viết lại được, không chỉ thế, mà còn làm được tí thơ!

Bài viết về cô, Cầm Dương Xanh, được một vị nữ độc giả, Bắc

Kít, Hà Lội, mê quá, bệ ngay về trang FB của cô.

Cô tình cờ thấy trang TV, trong khi lướt net, tìm tài liệu về Camus.

Book of Fantasy

1 YEAR AGO TODAY Tue, Sep 30, 2014 SÁNG TẠO số 3 - tháng 12/ 1956 - "Những ngón tay bắt được của trời"

http://huyvespa.blogspot.com/…/sang-tao-so-3-thang-12-1956-…

"- Những tờ báo mà tôi đã chủ trương thì

nó là cái dàn phóng, cái plate-forme,

cái tribune commune, nói chung là như vậy, tụ họp mọi

người lại đấy để cho có một chỗ đất đứng rồi thì anh muốn

làm gì thì làm. Nó chỉ là một

chỗ départ, một chỗ để khởi hành. Bây giờ nếu tôi

khoẻ trở lại thì tôi cũng làm y như vậy. Làm

một chỗ để đứng. Tôi rất yêu cái tinh thần, tinh thần

thật ở Pháp. Camus. Bon. Sartre. Bon. Tôi chịu ảnh hưởng của

mấy người đó. ...Tôi cho là họ rất hay. Thành

ra tờ Sáng Tạo mới có những tiểu đề ở dưới gọi là Diễn

đàn văn học nghệ thuật hôm nay - aujourd'hui, chứ không

có hiện đại gì cả"

(MAI THẢO trả lời phỏng vấn THỤY KHÊ 1997)

1 YEAR AGO TODAY Mon, Sep 29, 2014 Biển Buổi chiều đứng trên bãi Wasaga

Nhìn hồ Georgian

Cứ nghĩ thềm bên kia là quê nhà. ... See More

Mít vs Lò Thiêu Người

The Gulag can be regarded as the quintessential expression of modern Russian

society. This vast array of punishment zones across Russia, started in Tsarist

times and ending in the Soviet era, left a legacy on the Russian quest for

identity. In Russia, prison is usually referred to as the malinkaya zone

(small zone). The Russians have an expression for freedom: bolshaya zona,

(big zone). The distinction being that one is slightly less humane than the

other. But which one? A Russian friend once said, "First they make you work

in the factory, then they finish you off in prison." By the 1950s, the Gulag

played an integral role in the development of the Soviet economy. In fact,

Stalin used these camps as a source of economic stimulation, to excavate

the vast natural resources of the east and to stimulate growth and settlement

across the twelve time zones of the former USSR. The majority of mines, timber

industries, factories, and Russia's prized oil and gas fields were all discovered

through convict labour. In effect, almost every imaginable industry in Russia

today exists because of Stalin's policy. This photo was taken at the state

theatre in Vorkuta, a large city in the far north of Russia, beyond the Arctic

Circle, and one of the largest penal colonies created by the Soviet bureaucracy.

Today, survivors-both prisoner and guard-and their descendants still live

in this city. The woman was the lead in a play by Ostrovsky: Crazy Money.

www.donaldweber.com

Spring 2015

THE NEW QUARTERLY

Nếu không có cú dậy cho VC một bài học,

lũ Ngụy "vẫn sống ở Trại Tù", cùng với con cái của chúng.

Tờ Điểm Sách Nữu Ước, NYRB, có bài của Timothy Snyder,

về “Thế giới của Hitler”.

Tờ Người Nữu Ước, Adam Gopnik có bài

“Những ám ảnh của Hitler”.

Tin Văn post cả hai, và thủng thẳng

đi vài đường về nó. Một câu chuyện mới về Lò

Thiêu, như Adam Gopnik, tác giả bài viết trên tờ

Người Nữu Ước, phán.

Gulag

có thể được coi như là 1 biểu hiện cốt tuỷ của xã hội

hiện đại Nga. Không gian tù kể như khắp nước Nga, thời gian,

khởi từ chế độ phong kiến và chấm dứt cùng với thời kỳ Xô Viết, để

lại gia tài là cuộc truy tìm căn cước Nga. Ở Nga,

nhà tù thường được gọi là “vùng nhỏ”. Và

họ có 1 chữ để gọi tự do, “vùng lớn”.

Cái nào

“người” hơn cái nào?

Trước tiên, họ cho anh làm

ở nhà máy, sau nhà máy, thì tới nhà

tù.

Trong bài điểm cuốn Mùa Gặt Buồn của Conquest, Tolstaya phán,

chế độ Xô Viết chẳng hề phịa ra 1 thứ trừng phạt mới nào.

Chúng có sẵn hết, từ hồi phong kiến. Cái gọi là

thời ăn thịt người cũng có sẵn, từ thời Ivan Bạo Chúa.

Tất cả những nhận xét trên đây, áp dụng y chang

vào xứ Bắc Kít. Suốt bốn ngàn năm văn hiến, Bắc Kít

chưa từng biết đến tự do, dân chủ… là cái gì.

Những hình phạt thời kỳ phong kiến, đầy rẫy. Bạn thử chỉ cho Gấu, trong

lịch sử Bắc Kít, một giai thoại nào, liên quan, mắc mớ,

"nói lên" lòng nhân từ của… Bắc Kít?

Tô Hoài, thay vì gọi “Đàng Ngoài”, thì chỉ đích danh, “Quê Người”.

Ông biết, có 1 nơi đúng là Quê Nhà,

nhưng cùng với cái biết đó, là dã tâm

ăn cướp.

Hết phong kiến, thì lại đô hộ Tầu, hoặc xen kẽ, rồi bảo hộ Pháp.

Thời ăn thịt người cũng có.

Ăn thịt lợn, vỗ béo bằng thai nhi, thì cũng là ăn thịt người, vậy.

During Stalin's time, as I see it, Russian society, brutalized by centuries

of violence, intoxicated by the feeling that everything was allowed, destroyed

everything "alien": "the enemy," "minorities"-any and everything the least

bit different from the "average." At first this was simple and exhilarating:

the aristocracy, foreigners, ladies in hats, gentlemen in ties, everyone

who wore eyeglasses, everyone who read books, everyone who spoke a literary

language and showed some signs of education; then it became more and more

difficult, the material for destruction began to run out, and society turned

inward and began to destroy itself. Without popular support Stalin and his

cannibals wouldn't have lasted for long. The executioner's genius expressed

itself in his ability to feel and direct the evil forces slumbering in the

people; he deftly manipulated the choice of courses, knew who should be the

hors d' oeuvres, who the main course, and who should be left for dessert;

he knew what honorific toasts to pronounce and what inebriating ideological

cocktails to offer (now's the time to serve subtle wines to this group; later

that one will get strong liquor).

It is this hellish cuisine that Robert Conquest examines. And the leading

character of this fundamental work, whether the author intends it or not,

is not just the butcher, but all the sheep that collaborated with him, slicing

and seasoning their own meat for a monstrous shish kebab.

Tatyana Tolstaya

Lần trở lại xứ Bắc, về lại làng cũ, hỏi bà

chị ruột về Cô Hồng Con, bà cho biết, con địa chỉ, bố mẹ bị

bắt, nhà phong tỏa, cấm không được quan hệ, và cũng chẳng

ai dám quan hệ. Bị thương hàn, đói, và khát,

và do nóng sốt quá, khát nước quá, cô

gái bò ra cái ao ở truớc nhà, tới bờ ao thì

gục xuống chết.

Có thể cảm thấy đứa em quá đau khổ, bà an ủi, hồi đó “phong trào”.

Tolstaya viết:

Trong thời Stalin, như tôi biết,

xã hội Nga, qua bao thế kỷ sống dưới cái tàn bạo, bèn

trở thành tàn bạo, bị cái độc, cái ác

ăn tới xương tới tuỷ, và bèn sướng điên lên, bởi

tình cảm, ý nghĩ, rằng, mọi chuyện đều được phép, và

bèn hủy diệt mọi thứ mà nó coi là “ngoại nhập”:

kẻ thù, nhóm, dân tộc thiểu số, mọi thứ có tí

ti khác biệt với nhân dân chúng ta, cái

thường ngày ở xứ Bắc Kít. Lúc đầu thì thấy đơn

giản, và có tí tếu, hài: lũ trưởng giả, người

ngoại quốc, những kẻ đeo cà vạt, đeo kiếng, đọc sách, có

vẻ có tí học vấn…. nhưng dần dần của khôn người khó,

kẻ thù cạn dần, thế là xã hội quay cái ác

vào chính nó, tự huỷ diệt chính nó. Nếu

không có sự trợ giúp phổ thông, đại trà

của nhân dân, Stalin và những tên ăn thịt người

đệ tử lâu la không thể sống dai đến như thế. Thiên tài

của tên đao phủ, vỗ ngực xưng tên, phô trương chính

nó, bằng khả năng cảm nhận, dẫn dắt những sức mạnh ma quỉ ru ngủ đám

đông, khôn khéo thao túng đường đi nước bước, biết,

ai sẽ là món hors d’oeuvre, ai là món chính,

ai sẽ để lại làm món tráng miệng…

Đó là nhà bếp địa ngục mà Conquest săm soi. Và nhân vật dẫn đầu thì không

phải chỉ là tên đao phủ, nhưng mà là tất cả bầy cừu cùng cộng tác với hắn,

đứa thêm mắm, đứa thêm muối, thêm tí bột ngọt, cho món thịt của cả lũ.

Cuốn "Đại Khủng Bố", của Conquest, bản nhìn lại, a reassessment, do Oxford University Press xb, 1990.

Bài điểm sách, của Tolstaya, 1991.

GCC qua được trại tị nạn Thái Lan, cc 1990.

Như thế, đúng là 1 cơ may cực hãn hữu, được đọc nó, khi vừa mới Trại, qua

tờ Thế Kỷ 21, với cái tên “Những Thời Ăn Thịt Người”. Không có nó, là không

có Gấu Cà Chớn. Không có trang Tin Văn.

Có thể nói, cả cuộc đời Gấu, như 1 tên Bắc Kít, nhà quê, may mắn được ra

Hà Nội học, nhờ 1 bà cô là Me Tây, rồi được di cư vào Nam, rồi được đi tù

VC, rồi được qua Thái Lan... là để được đọc bài viết!

Bây giờ, được đọc nguyên văn bài điểm sách, đọc những đoạn mặc khải, mới

cảm khái chi đâu. Có thể nói, cả cái quá khứ của Gấu ở Miền Bắc, và Miền

Bắc - không phải Liên Xô - xuất hiện, qua bài viết.

Khủng khiếp thật!

Tatyana Tolstaya, trong một bài người viết tình cờ đọc đã

lâu, khi còn ở Trại Cấm, và chỉ được đọc qua bản dịch,

Những Thời Ăn Thịt Người (đăng trên tờ Thế Kỷ 21), cho rằng, chủ nghĩa

Cộng-sản không phải từ trên trời rớt xuống, cái tư duy

chuyên chế không phải do Xô-viết bịa đặt ra, mà

đã nhô lên từ những tầng sâu hoang vắng của lịch

sử Nga. Người dân Nga, dưới thời Ivan Bạo Chúa, đã từng

bảo nhau, người Nga không ăn, mà ăn thịt lẫn nhau. ["We Russians

don't need to eat; we eat one another and this satisfies us."].

Chính

cái phần Á-châu man rợ đó đã được đưa lên làm giai cấp nồng cốt xây dựng

xã hội chủ nghĩa. Bà khẳng định, nếu không có sự yểm trợ của nhân dân Nga,

chế độ Stalin không thể sống dai như thế. Puskhin đã từng van vái: Lạy Trời

đừng bao giờ phải chứng kiến một cuộc cách mạng Nga!

"God forbid we should ever witness a Russian revolt, senseless and merciless,"

our brilliant poet Pushkin remarked as early as the first quarter of the

nineteenth century.

Trong bài viết, Tolstaya kể, khi cuốn của Conquest, được tái

bản ở Liên Xô, lần thứ nhất, trên tờ Neva,

“last year” [1990, chắc hẳn], bằng tiếng Nga, tất nhiên, độc giả Nga, đọc,

sửng sốt la lên, cái gì, những chuyện này, chúng tớ biết hết rồi!

Bà giải thích, họ biết rồi, là do đọc Conquest, đọc

lén, qua những ấn bản chui, từ hải ngoại tuồn về!

Bản đầu tiên của nó, xb truớc đó 20 năm, bằng tiếng Anh, đã được tuồn vô

Liên Xô, như 1 thứ sách “dưới hầm”, underground, best seller.

Cuốn sách đạt

thế giá folklore, độc giả Nga đo lường lịch sử Nga, qua Conquest,"according to Conquest"

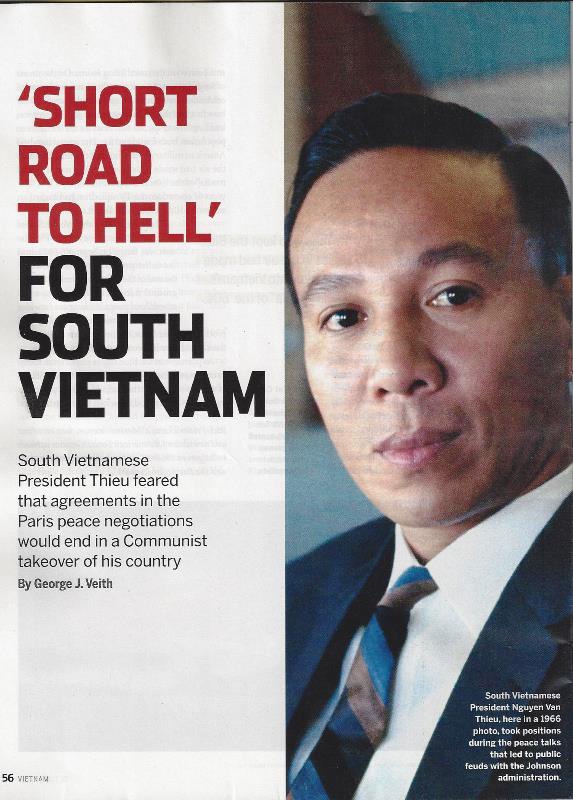

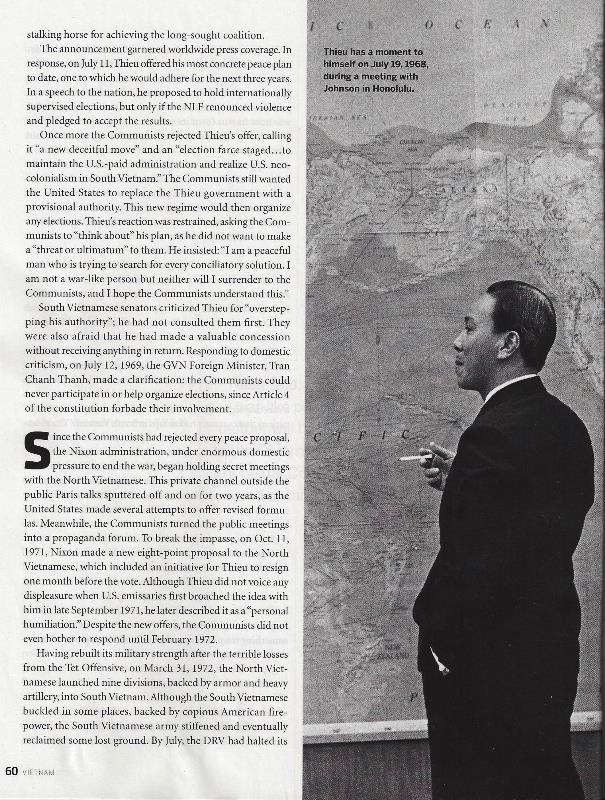

Nhân nhắc tới Tông Tông Thiệu.

Đường ngắn tới… Heo

Heo 1: Ngay sau 30 Tháng 4, 1975 cho lũ Ngụy

Heo 2: Dài dài sau đó, cho tới 40 năm sau, và sau nữa, cho xứ Mít.

Nhìn hình, thì thấy Tông Tông Thiệu bảnh trai hơn bất cứ 1 tên nào ở Bắc Bộ Phủ!

Được, được!

“Short road to Hell”, cụm từ này, là của tuỳ

viên báo chí của Tông Tông Thiệu, phát biểu, khi Nixon và Kissinger tìm đủ

mọi cách đe dọa Thiệu, bắt ông phải ngồi vô bàn hội nghị ở Paris. Trên tờ

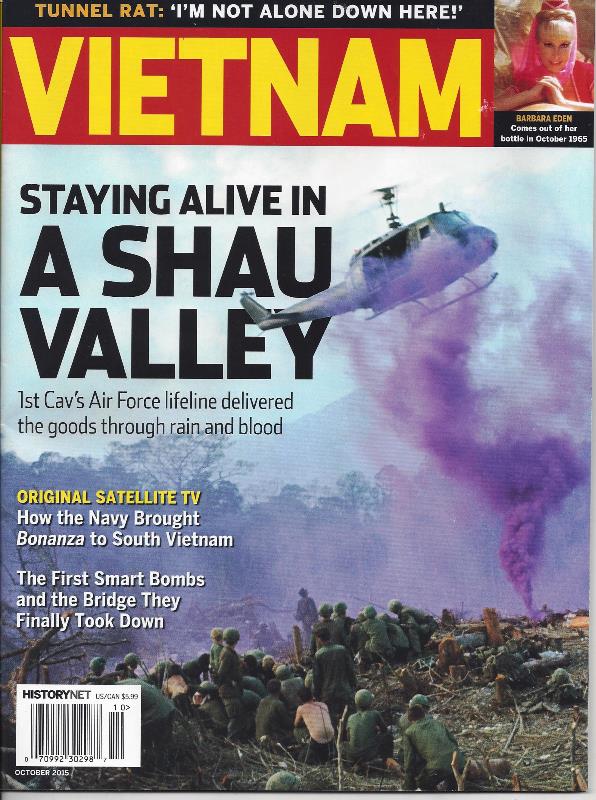

Vietnam, số mới nhất Tháng 10, 2015, có bài viết của J. Veith, tác giả Tháng

Tư Đen: Miền Nam thất thủ, Black April : The Fall of South Vietnam, 1973-75,

viết về cú bức tử Miền Nam của Nixon và Kissinger. Bài viết là từ cuốn New

Perceptions of the Vietnam War: Essays on the War: The South Vietnamese Experience,

The Diaspora, and the Continuing Impact, do Nathalie Huynh Chau Nguyen biên

tập:

Sau khi dụ khị đủ mọi cách, Thiệu vẫn lắc đầu, Nixon dọa cắt hết

viện trợ Mẽo, nếu không chịu ký hòa đàm.

After persuasion had failed, Nixon threatened Thieu with the cessation of all American aid if he did not sign the accords

Tổng Lú nhớ đọc nhe, vừa hôn đít O bá mà, vừa đọc nhe!

Hôn rồi, về xứ Mít đọc, cũng được!

Chúng ta giả dụ, sau khi Mẽo lại đi đêm với Tập, như Kissingger

đã từng đi đêm với Mao, chúng yêu cầu, thịt thằng

VC Mít nhe?

[Ngụy đọc khúc này, sướng nhé!]

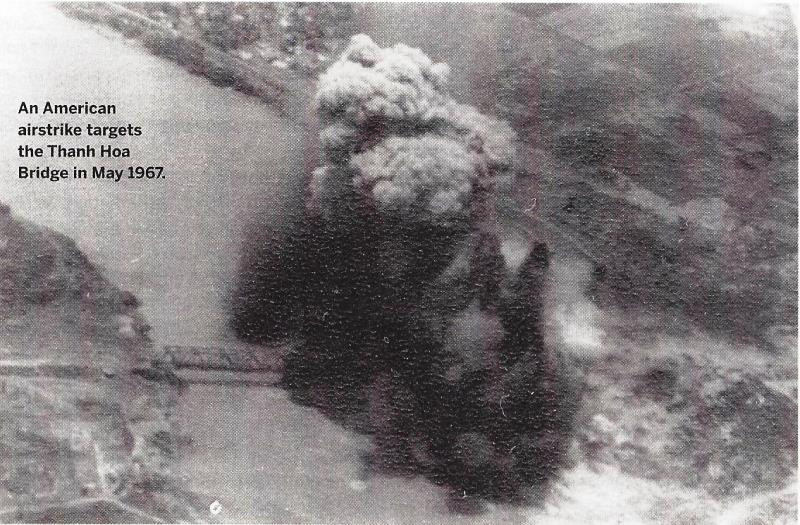

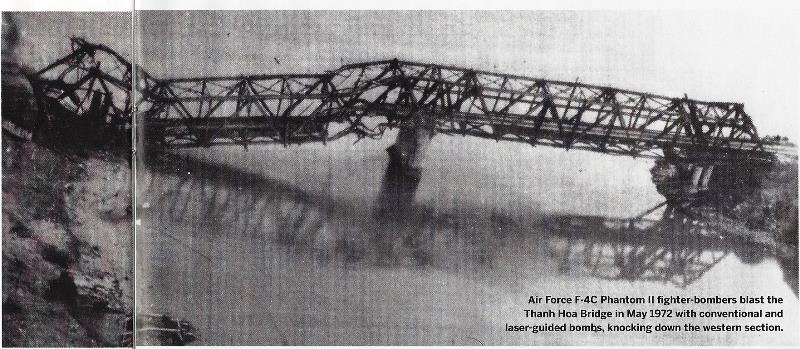

Mẽo dùng bom khôn đánh sập cầu Hàm Rồng [the Dragon's Jaw]

Cuốn sách những sinh vật tưởng tượng

Viết mỗi ngày

Borges

Conversations

In Memory of Borges

In Memory of Borges

Tiểu thuyết bắt buộc phải “mua vui thì cũng được vài trống canh”?

It is essential that a novel be enjoyed?

[Graham] Greene: Tôi không chắc. Những quả có cái

gọi là thú đau thương ở nơi người đọc.

I am not sure. There may be a certain masochism in the reader.

Nhân vật đàn bà nào ông khoái nhất trong những cuốn tiểu thuyết của ông?

Chắc là độc giả không đồng ý với tôi, nhưng có

thể nhân vật trong Kết Thúc Một Chuyện Tình, The End of the Affair.

Tôi nhận được 1 lời khen từ Theodora Benson, một nữ văn sĩ, cùng

thời với tôi. Bà viết, không phải tôi viết, mà

là 1 người đàn bà giúp tôi viết. Tuyệt.

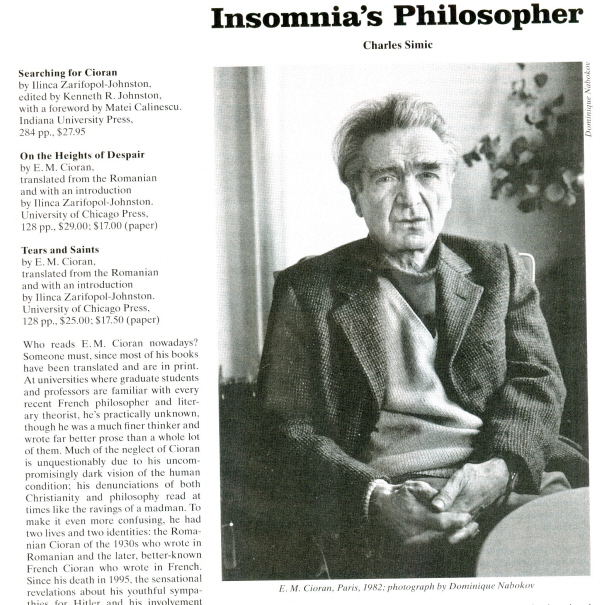

Có lẽ đã đến lúc cần nghiêm túc nghĩ đến

việc mở

một chuyên đề đích thực về Cioran :p

Blog NL

Bài viết về Ciroran của Charles Simic thật tuyệt. Gấu cứ tính đi hoài, mà cứ lu bu hoài.

Mới lật ra đi 1 đường loáng thoáng, vớ được câu này thật tuyệt:

Con người, bị đá văng ra khỏi Thiên Đàng, với 1 tí

tưởng tượng, đủ cho nó cảm thấy đời mình sao rất đỗi bi thương!

Ui chao, hồi còn trẻ, bị em bỏ, bị cuộc chiến hành, không

làm sao dám bỏ chạy, đúng là tâm trạng

Gấu khi đó.

Những ngày Mậu Thân căng thẳng,

Đại Học

đóng cửa, cô bạn về quê, nỗi nhớ bám riết vào da thịt thay cho cơn bàng

hoàng

khi cận kề cái chết theo từng cơn hấp hối của thành phố cùng với tiếng

hỏa tiễn

réo ngang đầu. Trong những giờ phút lặng câm nhìn bóng mình run rẩy

cùng với

những thảm bom B52 rải chung quanh thành phố, trong lúc cảm thấy còn

sống sót,

vẫn thường tự hỏi, phải yêu thương cô bạn một cách bình thường, giản dị

như thế

nào cho cân xứng với cuộc sống thảm thương như vậy...

Bạn đọc TV để ý, không có chấm câu. Câu văn dài thòng, như bè rau ruống!

Cô bạn, cô phù dâu ngày nào, Gấu gặp

lại ở hải ngoại. Cô phán, cực kỳ bi thương, cực kỳ hạnh phúc,

tại làm sao mà bao nhiêu năm trời, tình cảm của

anh dành cho tôi vẫn như ngày nào.

Nhờ gặp lại cô, Gấu viết lại được, không chỉ thế, mà còn làm được tí thơ!

Bài viết về cô, Cầm Dương Xanh, được một vị nữ độc giả, Bắc

Kít, Hà Lội, mê quá, bệ ngay về trang FB của cô.

Cô tình cờ thấy trang TV, trong khi lướt net, tìm tài liệu về Camus.

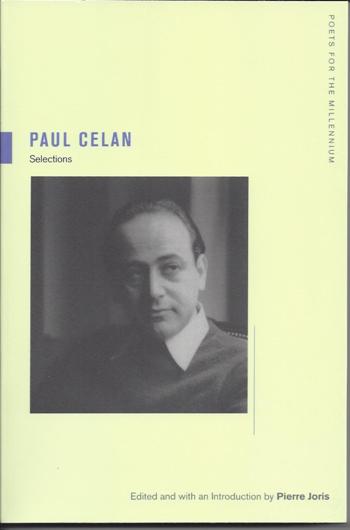

Cầm

Dương Xanh

ENCOUNTERS

WITH PAUL CELAN

E. M. CIORAN

Précis de decomposition, my first book written in

French,

was published in I949 by Gallimard. Five works of mine had been

published in

Romanian. In 1937, I arrived in Paris on a scholarship from the

Bucharest

Institut francais, and I have never left. It was only in I947, though,

that I

thought of giving up my native language. It was a sudden decision.

Switching

languages at the age of thirty-seven is not an easy undertaking. In

truth, it

is a martyrdom, but a fruitful martyrdom, an adventure that lends

meaning to

being (for which it has great need!). I recommend to anyone going

through a

major depression to take on the conquest of a foreign idiom, to

reenergize

himself, altogether to renew himself, through the Word. Without my

drive to conquer

French, I might have committed suicide. A language is a continent, a

universe,

and the one who makes it his is a conquistador. But let us get to the

subject.

...

The German

translation of the Précis proved

difficult. Rowohlt, the publisher, had engaged an unqualified woman,

with

disastrous resuits. Someone else had to be found. A Romanian writer,

Virgil Ierunca,

who, after the war, had edited a literary journal in Romania, in which

Celan's

first poems were published, warmly recommended him. Celan, whom I knew

only by

name, lived in the Latin quarter, as did 1. Accepting my offer, Celan

set to

work and managed it with stunning speed. I saw him often, and it was

his wish

that I read closely along, chapter by chapter, as he progressed,

offering

possible suggestions. The vertiginous problems involved in translation

were at that

time foreign to me, and I was far from assessing the breadth of it.

Even the

idea that one might have a committed interest in it seemed rather

extravagant

to me. I was to experience a complete reversal, and, years later, would

come to

regard translation as an exceptional undertaking, as an accomplishment

almost

equal to that of the work of creation. I am sure, now, that the only

one to

understand a book thoroughly is someone who has gone to the trouble of

translating it. As a general rule, a good translator sees more clearly

than the

author, who, to the extent that he is in the grips of his work, cannot

know its

secrets, thus its weaknesses and its limits. Perhaps Celan, for whom

words were

life and death, would have shared this position on the art of

translation.

In 1978,

when Klett was reprinting Lehre vom Zerfall

(the German Précis), I was asked to correct any errors

that might exist. I was

unable to do it myself, and refused to engage anyone else. One does not

correct Celan. A few months before he

died, he said to me that he would like to review the complete text.

Undoubtedly, he would have made numerous revisions, since, we must

remember,

the translation of the Précis dates

back to the beginning of his career as a translator. It is really a

wonder that

a noninitiate in philosophy dealt so extraordinarily well with the

problems

inherent in an excessive, even provocative, use of paradox that

characterizes

my book.

Relations

with this deeply torn being were not simple. He clung to his biases

against one

person or another, he sustained his mistrust, all the more so because

of his

pathological fear of being hurt, and everything hurt him. The slightest

indelicacy, even unintentional, affected him irrevocably. Watchful,

defensive

against what might happen, he expected the same attention from others,

and

abhorred the easygoing attitude so prevalent among the Parisians,

writers or

not. One day, I ran into him in the street. He was in a rage, in a

state

nearing despair, because X, whom he had invited to have dinner with

him, had

not bothered to come. Take it easy, I said to him, X is like that, he

is known

for his don't-give-a-damn attitude. The only mistake was expecting him.

Celan,

at that time, was living very simply and having no luck at all finding

a decent

job. You can hardly picture him in an office. Because of his morbidly

sensitive

nature, he nearly lost his one opportunity.

The very day

that I was going to his home to lunch with him, I found out that there

was a

position open for a German instructor at the Ecole normale supérieure,

and that

the appointment of a teacher would be imminent. I tried to persuade

Celan that

it was of the utmost importance for him to appeal vigorously to the

German

specialist in whose hands the matter resided. He answered that he would

not do

anything about it, that the professor in question gave him the cold

shoulder,

and that he would for no price leave himself open to rejection, which,

according to him, was certain. Insistence seemed useless.

Returning

home, it occurred to me to send him by pneumatique,

a message in which I pointed out to him the folly of allowing such an

opportunity

to slip away. Finally he called the professor, and the matter was

settled in a

few minutes. "I was wrong about him," he told me later. I won't go so

far as to propose that he saw a potential enemy in every man; however,

what was

certain was that he lived in fear of disappointment or outright

betrayal. His

inability to be detached or cynical made his life a nightmare. I will

never

forget the evening I spent with him when the widow of a poet had, out

of

literary jealousy, launched an unspeakably vile campaign against him in

France

and Germany, accusing him of having plagiarized her husband. "There

isn't

anyone in the world more miserable than I am," Celan kept saying. Pride

doesn't soothe fury, even less despair.

Something

within him must have been broken very early on, even before the

misfortunes

which crashed down upon his people and himself. I recall a summer

afternoon

spent at his wife's lovely country place, about forty miles from Paris.

It was

a magnificent day.

Everything

invoked relaxation, bliss, illusion. Celan, in a lounge chair, tried

unsuccessfully to be lighthearted. He seemed awkward, as if he didn't

belong,

as though that brilliance was not for him. What can I be looking for

here? he

must have been thinking. And, in fact, what was he seeking in the

innocence of

that garden, this man who was guilty of being unhappy, and condemned

not to

find his place anywhere? It would be wrong to say that I felt truly ill

at

ease; nevertheless, the fact was that everything about my host,

including his

smile, was tinged with a pained charm, and something like a sense of

nonfuture.

Is it a

privilege or a curse to be marked by misfortune? Both at once. This

double face

defines tragedy. So Celan was a figure, a tragic being. And for that he

is for

us somewhat more than a poet .

E. M. Cioran, "Encounters

with

Paul Celan," in Translating Tradition: Paul Celan in France, edited by

Benjamin Hollander (San Francisco: ACTS 8/9,1988): 151-52.

Is it a

privilege or a curse to be marked by misfortune? Both at once. This

double face

defines tragedy. So Celan was a figure, a tragic being. And for that he

is for

us somewhat more than a poet .

Đặc quyền,

hay trù ẻo, khi nhận "ân sủng" của sự bất hạnh?

Liền tù tì cả

hai!

Cái bộ mặt

kép đó định nghĩa thế nào là bi kịch.

Và như thế, Celan là 1 hình tượng, một

con người bi thương.

Và như thế, ông bảnh hơn nhiều, chứ không "chỉ là 1 nhà

thơ"!

Book of Fantasy

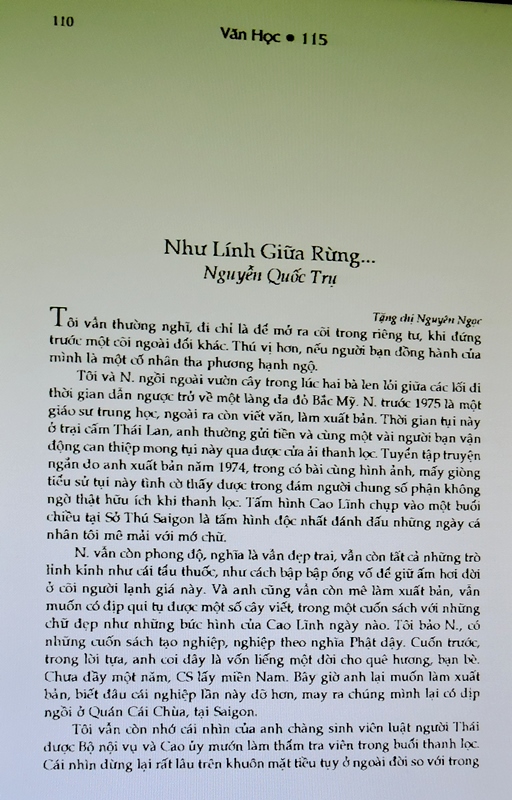

Note: Bài viết này, nhờ Văn Học

đưa lên lưới, đọc lại được, bằng cách chụp. Đọc, không

nhận ra đã từng viết.

Thú nhất, là cái mẩu viết về phê bình gia, trong bài tạp ghi.

RIP

Note: Trong nước mà sao rành thế?

Ngoài nước chưa thấy báo nào loan tin.

Nếu phải đặt

vào thế tam giác, với ba đỉnh, Gatsby-Le

Grand

Meaulnes-Một Chủ Nhật Khác, thì MCNK bảnh nhất, vì cái nền của

nó, là

cuộc

chiến Mít. Trong đời thực, Alain-Fournier,

trung

uý, tử trận năm 28 tuổi, tại khu rừng Saint-Rémy, ngày 22 tháng Chín

năm 1914.

Kiệt nhân vật của MCNK thì bị lầm là VC và bị bắn chết, khi đang ở nhà

thương,

mò ra rừng Đà Lạt, ngó thông, nhưng

TTT, sĩ quan VNCH thì chết vì bịnh ở Mẽo.

Nếu coi

cuộc chiến khốn kiếp là Ngày Hội

Nhân Gian thì Một Chủ

Nhật Khác lại bảnh nhất trong những cuốn bảnh nhất, so với Anh

Môn Vĩ

Đại và Gatsby Vĩ Đại!

GCC thực sự không tin, cõi văn Mít lại có 1 cuốn như Một Chủ Nhật

Khác.

Khủng nhất, là đoạn Kiệt tiễn Hiền đi, rồi lại trở về, với vợ con, với

cuộc

chiến, để... chết.

Như vậy là Kiệt đã đi tới cõi

bên kia, lo xong cho Hiền, rồi lại trở lại cõi

bên này.

Trong vương quốc của những

người đã chết

Tôi vẫn thường tha thẩn đi về

Thơ của Gấu

Gấu ngờ rằng nơi mà Kiệt đưa

Hiền tới, rồi trở về, để chết, cùng

với cuộc chiến, là Lost Domain, Miền Đã Mất, ở trong Le

Grand

Meaulnes.

Bài Giáng cũng có một cõi Lost Domain của ông,

là thời gian 15 năm

chăn dê, vui đùa với chuồn chuồn, châu chấu, trước khi trở về đời, làm

Ông

Khùng giữa cõi Bọ.

Hậu thế sau này, có thể sẽ coi Một Chủ Nhật Khác, là tác phẩm

số 1 của

thời đại hoàng kim Miền Nam VNCH, hẳn thế!

Hơn thế, chứ sao lại hẳn thế!

*****

Date: Thu, 25 Mar 2010 20:04:13 +0000

Toi cung ban rat nhieu viec, tu "Viet", cho toi lam viec cho nha` tho, roi co`n ch^`ng, con , nhung viec khong ten nua.

"Anh có thật? Ngày chủ nhật kia có thật? Ngôi

chùa lộng gió có thật? Ngôi nhà trong đêm

thơ mộng khủng khiếp nhớ đời có thật? Em hỏi hoài... Những

tiếng nổ ở phi trường buổi sáng em đi thì chắc chắn có

thật. Chúng nổ inh trong tai em, gây rung chuyển hết thẩy. Những

nụ hôn chia biệt cũng có thật, còn hằn rát bên

má em, không biết bao giờ phai...

Chiều nay Saigon đổ trận mưa đầu mùa. Trên ấy mưa chưa? Anh

vẫn ngồi quán cà phê buổi chiều? Anh có lên

uống rượu ở P.? Anh có trở lại quán S., với ai lần nào

không? Sắp đến kỳ thi. Năm nay em không có mặt để nhìn

trộm anh đi đi lại lại trong phòng, mặc quân phục đeo súng

một cách kỳ cục. Anh có đội thêm nón sắt không?

Năm đầu tiên em gọi anh là con Gấu. Hỗn như Gấu, đối với nữ

sinh viên. Em có ngờ đâu anh là Yêu Râu

Xanh...

MCNK

Cái mail có thiệt. Mới kiếm lại được.

Tưởng người đã đi xa

Nhưng người vưỡn lại về!

Tôi không tin cái ác, tôi tin cái chết

Je ne crois pas au mal, je crois à la mort.

Bài phỏng vấn Amis là chính của số báo. Đọc OK

lắm. Amis là nhà văn mũi lõ Tây Phương đầu tiên

đụng vô đề tài Gulag. Như… Sến, thầy của ông là

Nabokov. Nabokov gần như không bao giờ đề cập tới đề tài này,

trong giả tưởng của mình. Ngược hẳn trò. Đây là

1 trong những câu hỏi hắc búa của tờ ML.

Từ từ, Gấu lèm bèm tiếp.

TV đã giới thiệu bài viết trên tờ Obs về cuốn này.

Auschwitz Tháng Tư 1942

Obs 20 & 26 Aout 2015

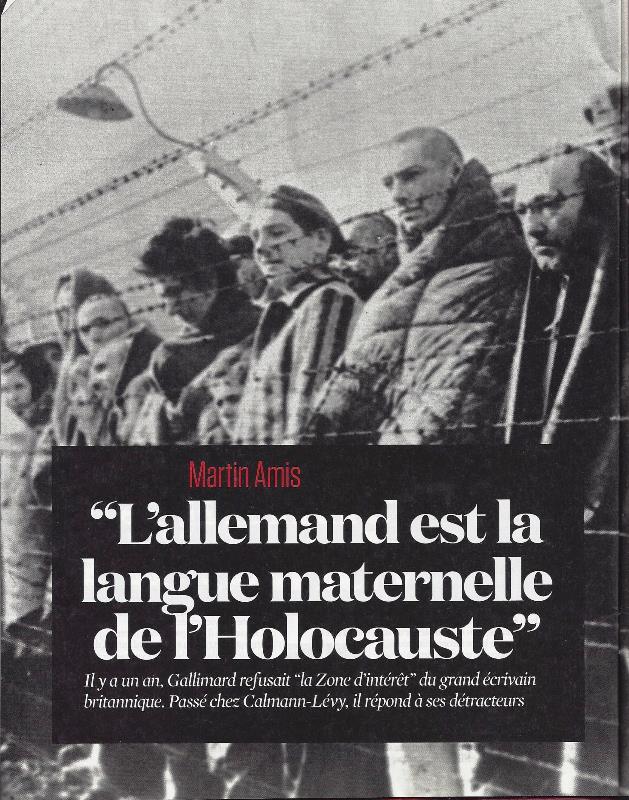

Tiếng Đức là tiếng mẹ đẻ của Lò Thiêu

Hãy nhớ rõ 1 điều, tiếng Đức không ngây thơ vô tội trước Lò Thiêu

G. Steiner: Phép Lạ Hổng

Martin Amis : "L’allemand est la langue maternelle de l’Holocauste"

http://bibliobs.nouvelobs.com/romans/20150818.OBS4359/martin-amis-l-allemand-est-la-langue-maternelle-de-l-holocauste.html

Tại làm sao mà ông

đặt tít cho cuốn sách của mình, là Miền Nhận

Hàng [la Zone d’intérêt: Miền Nam nhận họ, Miền Bắc nhận

hàng]?

[Note: Câu này, bản in trên báo có tí khác, bản trên net]

Tôi tính gọi nó là “Tuyết màu hạt dẻ”,

nhưng Simenon đã chơi cái tít “Tuyết dơ” rồi.

Nabokov phán, có hai thứ tít. Thứ lòi ra sau

khi viết xong, như người ta đặt tên cho đứa bé, khi nó

ra đời.

Thứ kia mới khủng, nó có từ trước, ngay từ đầu, nó cắm mẹ vô não của bạn

từ hổi nào hồi nào. Đây là trường hợp cuốn của tôi. Vùng nhận hàng, hay,

Miền Lợi Tức, là công thức mà Nazi sử dụng để chỉ Miền Lò Thiêu. Một cái

tít rõ ràng ngửi ra tiền.

Ui chao, thảo nào Bắc Kít gọi, Đàng Trong: Nhà

của chúng. Đàng Ngoài, là, tính nhượng

cho Tẫu!

Amis quả đúng là 1 nhà văn xì

căng đan. Cuốn sách mới xb của ông, bị Gallimard vứt vô

thùng rác, dù đây là nhà xb bạn

quí của ông. Cũng đếch thè m nói năng, phôn, phiếc gì hết.

Rồi 1 nhà xb Đức cũng chê. Sau cùng, nhà Calmann-Lévy

in nó. Theo tin hành lang, Gallimard chê, vì không

tới tầm.

Nhưng cuốn này, quả là khủng.

Gấu mê nhất cuốn Nhà Hội của ông. Có gần đủ sách

của ông, nhưng thú thực, không chịu nổi!

Trong số các quy luật sinh học,

tôi nhớ có cái quy luật này liên quan tới

tiến hóa: đó phải là sự tiến hóa của cả quần

thể. Không thể có tiến hóa ở từng cá thể riêng

lẻ.

Vương Trí Nhàn

Nhảm.

Quần thể tiến hóa sao bằng thời chống Mỹ Kíu Nước.

Đẻ ra thứ văn học sống bằng máu của kẻ khác.

Quần thể là đàn cừu. Không nghe Nobel Mít phán, sao?

Kundera chẳng đã kể, ném 1 con cừu xuống biển, là cả đàn cừu cứ thế nhảy theo? (1)

(1)

Kundera

coi tiểu thuyết là

sản phẩm của Âu châu. Và nó là một cuộc hôn nhân giữa sự không-nghiêm

trọng và

chuyện chết người. Chúng ta sẽ cùng với ông chứng kiến một cảnh trong

"Cuốn Sách Thứ Tư" của Rabelais. Giữa biển cả, chiếc thuyền của

Pantagruel gặp một con tầu chở cừu của mấy người lái buôn. Một người

trong bọn

thấy Panurge mặc quần không túi, cặp kiếng gắn lên nón, đã lên tiếng

chế riễu,

gọi là anh chàng mọc sừng. Panurge lập tức trả miếng: anh mua một con

cừu, rồi

ném nó xuống biển. Vốn có thói quen làm theo con đầu đàn, những con kia

cứ thế

nhào xuống nước....

Khi Koestler viết Bóng Đêm giữa Ban Ngày, ông chống

lại toàn thể tập thể, là… nhân loại.

Tức là đã tiên tri ra được sự cáo chung của chủ nghĩa CS.

Một đòn "cách sơn đả ngưu", như GCC đã từng viết, khi đọc 1 cuốn tiểu sử của Koestler:

"The final rout of the Soviet imperium in 1989-1990 began with the publication of Darkness at Noon"

David Cesarani: [Tiểu sử] Arthur Koestler: Một cái đầu không nhà, The homeless mind.

[Cú hỏng cẳng sau chót của uy quyền tối thượng của Xô

Viết, vào thời kỳ 1989-1990, bắt đầu, khi Bóng Đêm Giữa

Ban Ngày của Koestler ra lò, 1940].

Đúng là đòn "cách sơn đả ngưu"!

Từ bao nhiêu năm trước,

với con mắt cú vọ của một ký giả khi nhìn vào

sự kiện đời thường, tức diễn tiến những vụ án tại Moscow, mà

đã ngửi ra được tiếng chuông gọi hồn của chủ nghĩa Cộng Sản,

thì quả là cao thủ!

Khi Nguyễn Huy Thiệp viết Tướng Về Hưu, ông đã tiên tri

ra được Cái Ác Bắc Kít sẽ ngự trị toàn xứ Mít,

nảy sinh từ những con heo được nuôi bằng thai nhi.

Ông Vương Viên Ngoại này, do không biết viết sáng

tác là gì, nên phán nhảm.

Nhận xét về Nguyên Ngọc, qua nét vẽ của Xuân Sách

cũng sai, và làm sai luôn, những hậu quả sau đó.

NN cũng 1 thứ sống bằng máu của kẻ khác.

Những sáng tác của ông đâu phải sáng tác,

mà xúi người khác chết, cho ông ta sống.

Cái thứ sáng tác, thứ thật, là tiên tri

ra được sự thực sắp tới, do 1 cá nhân, bằng 1 cách nào

đó, thở trước hơi thở của quần thể.

Thơ tự do của TTT, lúc mới xuất hiện mà chẳng bị chửi tơi bời sao?

Isn't "we" the problem, that little words "we" (which I distrust so profoundly, which I would forbid the individual man to use).

Cái từ "chúng tôi" gây phiền phức, phải chăng,

cái từ nhỏ xíu "chúng tôi" (mà tôi

quá ghê tởm, đếch tin cậy, và cấm 1 cá nhân

1 con người xử dụng) -WITOLD GOMBROWICZ

Sacrifice the children-an old story, pre-Homeric-so that the nation will endure, to create a legend.

-ALEKSANDER WAT

Xúi con nít hy sinh, để có được những anh hùng Núp, trò này xưa lắm rồi.

Mistaken ideas always end in bloodshed, but in every case it is someone else's

blood. This is why our thinkers feel free to say just about everything.

-CAMUS

Tư tưởng lầm lạc luôn chấm dứt bằng máu, của kẻ khác, không phải của những tên như NN.

Levi Page

Bài mới nhất về Primo Levi trên The New Yorker

His friend Edith Bruck, herself a survivor of Auschwitz and Dachau,

said, “There are no howls in Primo’s writing—all emotion is

controlled—but Primo gave such a howl of freedom at his death.” This is

moving, certainly, and perhaps true. Thus one consoles oneself, and

consolation is necessary: like much suicide, Levi’s death is only a

silent howl, because it voids its own echo. It is natural to be

bewildered, and it is important not to moralize. For, above all, Job

existed and was not a parable. ♦

Không có gầm rú, gào thét trong cái

viết của Primo Levi - mọi xúc động đều được kiềm chế - nhưng Primo

đem đến tiếng gầm rú của tự do, với cái chết của mình.

Rằng, con người tự an ủi mình, và an ủi thì cần thiết:

giống như tự làm thịt mình, cái chết của Levi chỉ là

tiếng gầm rú của im lặng…

Thảo nào GCC cứ tính thử hoài, tiếng gầm rú của im lặng!

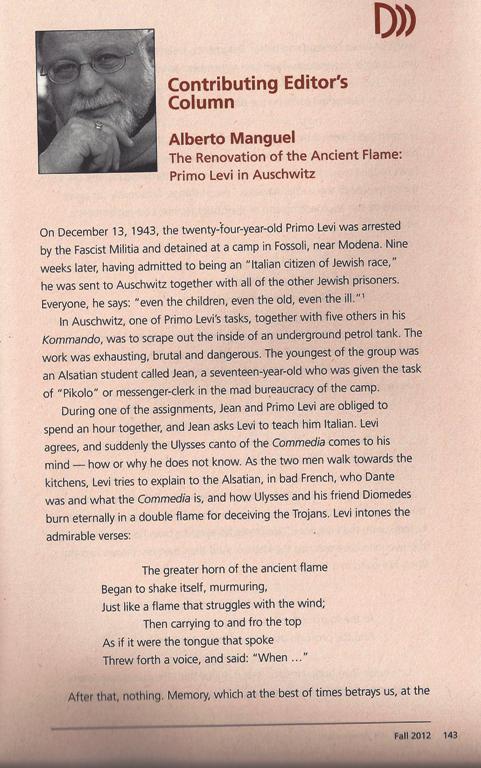

Làm mới Ngọn Lửa Cũ:

Primo Levi ở Lò Thiêu

Vào ngày 13 tháng Chạp 1943, Primo Levi, 24 tuổi, bị

Phát Xít Ý bắt. Chín tuần sau, khai là

công dân Ý gốc Do Thái, bèn bị tống vô

Lò Thiêu với tất cả những tù nhân Do Thái

khác. Tất cả, ngay cả trẻ con, người già, người bịnh.

Trong 1 lần cùng làm 1 ca với Jean, một tù nhân

17 tuổi, anh này nhờ Levi chỉ cho vài chiêu tiếng Ý,

thế là "Kịch Trời" của Dante bật ra trong đầu Levi.

Cái ngọn ngọn lửa, ngọn lửa cũ

Bắt đầu lắc lư, lầm bầm, lầu bầu

Như thể ngọn lửa đang chống cự với gió

Mang tới mang lui

Như cái lưỡi

Thì thào lời, “Khi mà….”

Chỉ có thế, là hết. Như thể hồi ức, vào những lúc

thật thầu sầu của nó, vưỡn phản bội chúng ta

Levi sometimes said that he felt a larger shame—shame

at being a human being, since human beings invented the world of the concentration

camp. But if this is a theory of general shame it is not a theory of original

sin. One of the happiest qualities of Levi’s writing is its freedom from

religious temptation. He did not like the darkness of Kafka’s vision, and,

in a remarkable sentence of dismissal, gets to the heart of a certain theological

malaise in Kafka: “He fears punishment, and at the same time desires it .

. . a sickness within Kafka himself.” Goodness, for Levi, was palpable and

comprehensible, but evil was palpable and incomprehensible. That was the

healthiness within himself.

How Primo Levi survived

Levi không chịu nổi Kafka. Ông nói ra điều này, khi dịch Kafka:

Một

sự hiếp đáp có tên là Kafka

Franz Kafka & Primo

Levi, tại sao?

Không phải tôi chọn,

mà là nhà xb. Họ đề nghị và tôi chấp

thuận. Kafka không hề là tác giả ruột của tôi. Nói đúng ra, thì là thế

này: Tôi

đã hơi coi nhẹ một việc dịch như vậy, bởi vì tôi không nghĩ, là mình sẽ

phải

cực nhọc với nó. Kafka không hề là một trong những tác giả mà tôi yêu

thích.

Tôi nói lý do tại sao: Không có gì là chắc chắn, về chuyện, những tác

phẩm mà

mình thích, thì có gì giông giống với những tác phẩm của mình, mà

thường là

ngược lại. Kafka đối với tôi, không phải là chuyện dửng dưng, hoặc buồn

bực, mà

là một tình cảm, một cảm giác thủ thế, phòng ngự. Tôi nhận ra điều này

khi dịch

Vụ Án. Tôi cảm thấy như bị cuốn sách hiếp đáp, bị nó tấn công. Và tôi

phải bảo

vệ, phòng thủ. Bởi vì đây là một cuốn sách rất tuyệt. Nhưng nó đâm thấu

bạn,

giống như một mũi tên, một ngọn lao. Độc giả nào cũng cảm thấy như bị

đưa ra

xét xử, khi đọc nó. Ngoài ra, ngồi thoải mái trong chiếc ghế bành với

cuốn sách

ở trên tay, khác hẳn chuyện hì hục dịch từng từ, từng câu. Trong khi

dịch tôi

hiểu ra lý do của sự thù nghịch (hostile) của tôi với Kafka. Đó là do

bản năng

tự vệ, phản xạ phòng ngự, do sợ hãi gây

nên. Có thể, còn một lý do xác đáng

hơn: Kafka là người Do Thái, tôi cũng là Do Thái.

Vụ Án bắt đầu bằng một chuyện bắt giam không dự đoán

trước được, và chẳng thể nào biện minh, nghề nghiệp viết lách

của tôi bắt đầu bằng một vụ bắt bớ không lường trước được và

chẳng thể biện minh. Kafka là một tác giả mà tôi

ngưỡng mộ, tuy không ưa, tôi sợ ông ta, giống như bị sao

quả tạ giáng cho một cú bất thình lình, hoặc

bị một nhà tiên tri nói cho bạn biết, bạn chết vào

ngày nào tháng nào.

Note: Bài dịch này, hân hạnh được Sến để mắt tới, cho đăng trên talawas. Tks. NQT

Đâu dễ gì được Sến để mắt tới!

Một chuyến đi

Một chuyến đi

Bài viết chót cho Văn Học NMG.

Viết về mấy ông bạn Trúc Chi, Tạ Chí Đại Trường... nhưng thực sự là về Nguyễn Tuân.

Cái tít là từ Nguyễn Tuân.

Nguyen Tuan...

07/07/2010

"Nguyễn Tuân nổi tiếng với tùy bút, và tùy

bút Nguyễn Tuân, nổi đình nổi đám vì chất

khinh bạc của nó. Những người viết sau này, không thể

nào tới được cái chất khinh bạc "ròng" như vậy, đành

phải thay bằng giọng thầy đời, giọng uyên bác, giọng có

đi Tây, đi Tầu, có ở Paris, có biết khu "dân sinh"

Saint-Germain-des-Prés... Ra cái điều đi hơn Nguyễn Tuân!

Trúc Chi có thể "hơn" Nguyễn Tuân ở cái khoản

đi, nhưng "may thay", chân truyền Nguyễn Tuân ở cái khoản

khinh bạc: khinh bạc như là cực điểm của lòng nhân hậu.

Lòng nhân hậu, hay hồn nhân hậu này, theo tôi

nên "dịch ra tiếng Tây" bằng chữ la nostalgie, vốn thường được

hiểu là hoài hương."

"Mot chuyen di" cua GNV hay qua. Nguoi trong nuoc cung dang viet hang loat

ve Nguyen Tuan, nhung khong hieu sao, doc ho cu co cam giac nhu dang nghe

mot nhom nguoi noi chuyen voi nhau trong mot... dam gio^~.

Mít vs Lò Thiêu Người

The Gulag can be regarded as the quintessential expression of modern Russian

society. This vast array of punishment zones across Russia, started in Tsarist

times and ending in the Soviet era, left a legacy on the Russian quest for

identity. In Russia, prison is usually referred to as the malinkaya zone

(small zone). The Russians have an expression for freedom: bolshaya zona,

(big zone). The distinction being that one is slightly less humane than the

other. But which one? A Russian friend once said, "First they make you work

in the factory, then they finish you off in prison." By the 1950s, the Gulag

played an integral role in the development of the Soviet economy. In fact,

Stalin used these camps as a source of economic stimulation, to excavate

the vast natural resources of the east and to stimulate growth and settlement

across the twelve time zones of the former USSR. The majority of mines, timber

industries, factories, and Russia's prized oil and gas fields were all discovered

through convict labour. In effect, almost every imaginable industry in Russia

today exists because of Stalin's policy. This photo was taken at the state

theatre in Vorkuta, a large city in the far north of Russia, beyond the Arctic

Circle, and one of the largest penal colonies created by the Soviet bureaucracy.

Today, survivors-both prisoner and guard-and their descendants still live

in this city. The woman was the lead in a play by Ostrovsky: Crazy Money.

www.donaldweber.com

Spring 2015

THE NEW QUARTERLY

Nếu không có cú dậy cho VC một bài học,

lũ Ngụy "vẫn sống ở Trại Tù", cùng với con cái của chúng.

Tờ Điểm Sách Nữu Ước, NYRB, có bài của Timothy Snyder,

về “Thế giới của Hitler”.

Tờ Người Nữu Ước, Adam Gopnik có bài

“Những ám ảnh của Hitler”.

Tin Văn post cả hai, và thủng thẳng

đi vài đường về nó. Một câu chuyện mới về Lò

Thiêu, như Adam Gopnik, tác giả bài viết trên tờ

Người Nữu Ước, phán.

Cuốn sách những sinh vật tưởng tượng

Viết mỗi ngày

In

March 1984, Jorge Luis Borges began a series of radio “dialogues” with

the Argentinian poet and essayist Osvaldo Ferrari, which have now been

translated into English for the first time

Everything exists in order to end up in a book, or everything leads to a book. nybooks.com

Cuốn này, Gấu mua từ hồi nào rồi. Câu NYRB trích, là của Mallarmé

Thế giới hiện

hữu để tiến tới một cuốn sách đẹp

Le monde

existe pour

aboutir à un beau livre.

Mallarmé.

Note: Mới tậu. Đi liền cú,

Borges lèm bèm về Kafka, nhân TV đang dịch Trước Pháp Luật:

Kafka Could

Be Part of Human Memory

Kafka có thể [có, là] phần hồi ức con người

Mới ra lò,

2014.

Tên nhà xb mới

thú: Seagull Books

www.seagullbooks.org

"Phần hồi ức con người" của Kafka, thì cũng giống như 1954 của TTT, với

hồi ức Mít: Chúng ta không thể nào hiểu được 1954 nếu thiếu "Bếp Lửa",

thí dụ vậy,

Ferrari hỏi

Borges, nghe người ta nói là, chúng ta không thể hiểu được lịch sử của

thời

chúng ta, nếu thiếu sự giúp đỡ của Kafka, Borges bèn trả lời, thì đúng

như thế,

nhưng quá thế nữa, Kafka quan trọng hơn lịch sử của chúng ta!

Ui chao em của

GCC, HA, trách Gấu, mi viết hoài về TTT, ở trên net, rồi mi chết,

thì mất liêu luôn, sao không chịu in ra giấy, vì TTT còn quan trọng hơn

cả hồi ức

Mít!

Hà, hà!

FERRARI. But

we are told that we cannot make a faithful interpretation of our times

without Kafka's help.

BORGES. Yes,

but Kafka is more important than our times....

Borges

Conversations

Hiền đâu rồi?

Duy, bạn Kiệt có lần hỏi chàng.

Độc giả MCNK cũng thắc mắc.

Liệu TTT, tác giả có khi nào thắc mắc?

Kiệt trả lời Thuỳ, bà vợ, anh đưa cô ta tới chỗ đó đó, rồi lại trở về với em!

Trong chưởng Kim Dung, cũng có nhân vật Khúc Phi Yến, xuất hiện 1 lần, rồi biến mất.

Manguel đi 1 bài thật là tuyệt vời về đề tài này.

TV post ở đây, rồi đi 1 đường lèm bèm sau.

Book of Fantasy

Saigon ngày nào của GCC

Bài Tạp Ghi đầu tiên viết cho Văn Học NMG. Tháng 9/1996.

Cái hình Saigon Kids, của Dirck Halstead, Sếp UPI ngày

nào của Gấu, lấy trên net

http://www.gio-o.com/LyOcBR/LyOcBrWisTom2baitho.htm

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1996 was awarded

to Wislawa Szymborska "for poetry that with ironic precision allows the historical

and biological context to come to light in fragments of human reality".

Giải Thưởng Nobel Văn Chương 1996 dành cho Wislawa Szymborska "vì

nền thi ca trào phúng chính xác cho phép

văn cảnh thuộc lịch sử và sinh học trong những mảnh đời nhân

thế được soi sáng".

Lý Ốc dịch

Theo GCC, dịch giả không thèm để ý đến “phân tích loại từ”, analyse grammaticale.

Trong cụm từ trên, precison là danh từ, ironic là tĩnh

từ, bổ nghĩa [modify] cho precison. Khi dịch ra tiếng Mít, ironic

biến thành danh từ.

Đúng ra phải dịch, đại khái, S được Nobel vì thơ của

bà, với sự chính xác có tính hài

hước, [nó] cho phép cái nội dung mang tính lịch

sử và sinh học, phơi ra trước ánh sáng, trong những

mẩu đoạn của thực tại con người.

Tiếng Việt không phân biệt rõ ràng về tự loại,

nhưng người dịch phải biết, nếu không, độc giả không biết đuờng

nào mà lần!

Hơn nữa 1 vòng hoa Nobel là cả 1 kỳ công của Viện Hàn

Lâm. Làm sao chỉ vài chữ, mà nói lên

được cả hai, một, cõi văn của người được, và một, cái

tôn chỉ của giải Nobel.

Going Home

He came home. Said nothing.

It was clear, though, that something had gone wrong.

He lay down fully dressed.

Pulled the blanket over his head.

Tucked up his knees.

He's nearly forty, but not at the moment.

He exists just as he did inside his mother's womb,

clad in seven walls of skin, in sheltered darkness.

Tomorrow he'll give a lecture

on homeostasis in metagalactic cosmonautics.

For now, though, he has curled up and gone to sleep.

Wislawa Szymborska

Về Nhà

Chàng về nhà. Nín thinh không nói.

Rõ ràng, dù sao, đã có chuyện gì trắc trở.

Chàng nằm dài để nguyên bộ cánh.

Kéo mền trùm kín mít.

Co quắp hai gối chèo queo.

Chàng gần tứ thập, nhưng lắm lúc như em thơ.

Chàng hiện hữu như là bào thai trong bụng mẹ,

gói giữa bảy lớp thành da, ẩn trú trong cõi huyền thiên sâu thẳm.

Ngày mai chàng sẽ đọc một diễn văn

về sự cân bằng trong những chuyến du hành ngoài vũ trụ.

Còn bây giờ, dù sao, chàng cũng đã cuộn mình trôi vào giấc ngủ.

Lý Ốc dịch

Vv “chính xác tiếu lâm”.

Nếu đúng như thế, thì “not at the moment” không thể dịch

là “lắm lúc như trẻ thơ được”, mà phải dịch “không,

vào lúc này”, vì tác giả giải thích,

lúc này, chàng như con sâu nằm trong bụng mẹ,

và đây là ý nghĩa của từ “về nhà”!

The Disquieting Resonance of 'The Quiet

American'

by Pico Iyer

April 21, 2008 5:08 PM ET

Note: Bài viết này, nhờ Văn Học

đưa lên lưới, đọc lại được, bằng cách chụp. Đọc, không

nhận ra đã từng viết.

Thú nhất, là cái mẩu viết về phê bình gia, trong bài tạp ghi.

Mít vs Lò Thiêu Người

The Gulag can be regarded as the quintessential expression of modern Russian

society. This vast array of punishment zones across Russia, started in Tsarist

times and ending in the Soviet era, left a legacy on the Russian quest for

identity. In Russia, prison is usually referred to as the malinkaya zone

(small zone). The Russians have an expression for freedom: bolshaya zona,

(big zone). The distinction being that one is slightly less humane than the

other. But which one? A Russian friend once said, "First they make you work

in the factory, then they finish you off in prison." By the 1950s, the Gulag

played an integral role in the development of the Soviet economy. In fact,

Stalin used these camps as a source of economic stimulation, to excavate

the vast natural resources of the east and to stimulate growth and settlement

across the twelve time zones of the former USSR. The majority of mines, timber

industries, factories, and Russia's prized oil and gas fields were all discovered

through convict labour. In effect, almost every imaginable industry in Russia

today exists because of Stalin's policy. This photo was taken at the state

theatre in Vorkuta, a large city in the far north of Russia, beyond the Arctic

Circle, and one of the largest penal colonies created by the Soviet bureaucracy.

Today, survivors-both prisoner and guard-and their descendants still live

in this city. The woman was the lead in a play by Ostrovsky: Crazy Money.

www.donaldweber.com

Spring 2015

THE NEW QUARTERLY

Nếu không có cú dậy cho VC một bài học,

lũ Ngụy "vẫn sống ở Trại Tù", cùng với con cái của chúng.

Tờ Điểm Sách Nữu Ước, NYRB, có bài của Timothy Snyder,

về “Thế giới của Hitler”.

Tờ Người Nữu Ước, Adam Gopnik có bài

“Những ám ảnh của Hitler”.

Tin Văn post cả hai, và thủng thẳng

đi vài đường về nó. Một câu chuyện mới về Lò

Thiêu, như Adam Gopnik, tác giả bài viết trên tờ

Người Nữu Ước, phán.

The Bloi and the Morlocks

The hero of the novel The Time Machine, which a young writer Herbert

George Wells published in 1895, travels on a mechanical device into an unfathomable

future. There he finds that mankind has split into two species: the Eloi,

who are frail and defenseless aristocrats living in idle gardens and feeding

on the fruits of the trees; and the Morlocks, a race of underground proletarians

who, after ages of laboring in darkness, have gone blind, but driven by the

force of the past, go on working at their rusted intricate machinery that

produces nothing. Shafts with winding staircases unite the two worlds. On

moonless nights, the Morlocks climb up out of their caverns and feed on the

Eloi.

The nameless hero, pursued by Morlocks, escapes back into

the present. He brings with him as a solitary token of his adventure

an unknown flower that falls into dust and that will not blossom on earth

until thousands and thousands of years are over.

Nguỵ vs VC

Nhân vật chính trong cuốn tiểu thuyết “Máy Thời Gian”,

sử dụng cái máy thần sầu du lịch xuyên qua thời gian

tới những miền tương lai không làm sao mà dò được.

Ở đó, anh ta thấy Mít – nhân loại - được chia thành

hai, một, gọi là Ngụy, yếu ớt, ẻo lả, và là những nhà

trưởng giả, bất lực, vô phương chống cự, sống trong những khu

vườn nhàn nhã, ăn trái cây, và một, VC,

gồm những tên bần cố nông, vô sản, sống dưới hầm, địa

đạo [Củ Chi, thí dụ], và, do bao nhiêu đời lao động trong

bóng tối, trở thành mù, và, được dẫn dắt bởi

sức mạnh kẻ thù nào cũng đánh thắng, với sức người sỏi

đá cũng thành cơm, cứ thế cứ thế lao động, để thâu hoạch

chẳng cái gì. Có những cầu thang nối liền hai thế giới,

và vào những đêm không trăng, VC, từ những hang

động, hầm hố, bò lên làm thịt lũ Ngụy.

Nhân vật chính, không tên, bị VC truy đuổi, trốn

thoát được, và trở lại thời hiện tại. Anh ta mang theo cùng

với anh, một BHD, như chứng tích của cuộc phiêu lưu, và

vừa trở lại hiện tại, bông hồng bèn biến thành tro bụi,

và, như…. Cô Sáu trong Tiền Kiếp Của GCC, hàng

hàng đời sau, sẽ có ngày nào đó, bông

hồng lại sống lại…

Who knows?

Hà, hà!

The Tigers of Annam

To the Annamites, tigers, or spirits who dwell in tigers, govern the four

corners of space. The Red Tiger rules over the South (which is located at

the top of maps); summer and fire belong to him. The Black Tiger rules over

the North; winter and water belong to him. The Blue Tiger rules over the

East; spring and plants belong to him. The White Tiger rules over the West;

autumn and metals belong to him.

Over these Cardinal Tigers is a fifth tiger, the

Yellow Tiger, who stands in the middle governing the others, just as the

Emperor stands in the middle of China and China in the middle of the World.

(That's why it is called the Middle Kingdom; that's why it occupies the middle

of the map that Father Ricci, of the Society of Jesus, drew at the end of

the sixteenth century for the instruction of the Chinese.)

Lao-tzu entrusted to the Five Tigers the mission of waging

war against devils. An Annamite prayer, translated into French by Louis Cho

Chod, implores the aid of the Five Heavenly Tigers. This superstition is

of Chinese origin; Sinologists speak of a White Tiger that rules over the

remote region of the western stars. To the South the Chinese place a Red

Bird; to the East, a Blue Dragon; to the North, a Black Tortoise. As we see,

the Annamites have preserved the colors but have made the animals one.

The Sphinx

The Sphinx of Egyptian monuments (called by Herodotus androsphinx, or man-sphinx,

in order to distinguish it from the Greek Sphinx) is a lion having the head

of a man and lying at rest; it stood watch by temples and tombs: and is said

to have represented royal authority. In the halls of Karnak, other Sphinxes

have the head of a ram, the sacred animal of Amon. The Sphinx of Assyrian

monuments is a winged bull with a man's bearded and crowned head; this image

is common on Persian gems. Pliny in his list of Ethiopian animals includes

the Sphinx, of which he details no other features than "brown hair and two

mammae on the breast."

The Greek Sphinx has a woman's head and breasts, the wings

of a bird, and the body and feet of a lion. Some give it the body of a dog

and a snake's tail. It is told that it depopulated the Theban countryside

asking riddles (for it had a human voice) and making a meal of any man who

could not give the answer. Of Oedipus, the son of Jocasta, the Sphinx asked,

"What has four legs, two legs, and three legs, and the more legs it has the

weaker it is?" (So runs what seems to be the oldest version. In time the

metaphor was introduced which makes of man's life a single day. Nowadays

the question goes, "Which anima] walks on four legs in the morning, two legs

at noon, and three in the evening?") Oedipus answered that it was a man 'who

as an infant crawls on all fours, when he grows up walks on two legs, and

in old age leans on a staff. The riddle solved, the Sphinx threw herself

from a precipice.

De Quincey, around 1849, suggested a second interpretation,

which complements the traditional one. The subject of the riddle according

to him is not so much man in general as it is Oedipus in particular, orphaned

and helpless at birth, alone in his manhood, and supported by Antigone in

his blind and hopeless old age.

Trả

lời phỏng vấn của tờ báo Nhật Shûkan Posuto ngày 17/8/1979, ở cao điểm

của làn sóng thuyền nhân Việt Nam lênh đênh trên Biển Đông, triết gia

Pháp Michel Foucault, đồng tham gia Ủy ban vận động "Một chiếc tàu cho

Việt Nam", nhận định rằng di dân sẽ trở thành một vấn nạn đầy đau đớn và

bi thảm của hàng triệu người mà những gì đang xảy ra ở Việt Nam là điềm

báo. Điềm báo ấy đã trở thành hiện thực trong Khủng hoảng Di dân hiện

tại ở châu Âu. Những ngày này, sống ở một trong n... ****

Note: Re Foucalt

2. Michel Foucault: Nguồn

gốc

vấn đề người Việt tị nạn.

Lời người giới thiệu: Sau đây

là chuyển ngữ, từ bản tiếng Pháp, cuộc phỏng vấn đặc biệt triết gia

người Pháp,

Michel Foucault, đăng trên tạp chí Nhật Bản, Shukan posuto, số đề ngày

17 tháng

Tám 1979. Nhan đề tiếng Nhật: "Nanmin mondai ha 21 seiku minzoku daiidô

no

zencho da." ("Vấn đề người tị nạn là điềm báo trước cuộc di dân lớn

lao mở đầu thế kỷ 21"). Người phỏng vấn: H. Uno. Người dịch ra tiếng

Pháp:

R. Nakamura.

Người phỏng vấn: Theo ông,

đâu là cội nguồn của vấn đề người Việt tị nạn?

Michel Foucault: Việt Nam

không ngừng bị chiếm đóng, trong một thế kỷ, bởi những thế lực quân sự

như

Pháp, Nhật, và Mỹ. Và bây giờ cựu-Miền Nam bị chiếm đóng bởi cựu-Miền

Bắc. Chắc

chắn, cuộc chiếm đóng Miền Nam bởi Miền Bắc thì khác những cuộc chiếm

đóng

trước đó, nhưng đừng quên rằng, quyền lực Việt Nam của Miền Nam hiện

nay, là thuộc

về Việt Nam của Miền Bắc. Suốt một chuỗi những chiếm đóng trong một thế

kỷ như

thế đó, những đối kháng, xung đột quá đáng đã xẩy ra ở trong lòng dân

chúng.

Con số những người cộng tác với kẻ chiếm đóng, không nhỏ, và phải kể cả

ở đây,

những thương gia làm ăn buôn bán với những người bản xứ, hay những công

chức

trong những vùng bị chiếm đóng. Do những đối kháng lịch sử này, một

phần dân

chúng đã bị kết án, và bị bỏ rơi.

-Rất nhiều người tỏ ra nhức

nhối, vì nghịch lý này: trước đây, phải hỗ trợ sự thống nhất đất nước

Việt Nam,

và bây giờ, phải đối diện với hậu quả của việc thống nhất đó: vấn đề

những

người tị nạn.

Nhà nước không có quyền sinh

sát - muốn ai sống thì được sống, muốn ai chết thì người đó phải chết -

với dân

chúng của mình cũng như dân chúng của người – của một xứ sở khác. Chính

vì

không chấp nhận một thứ quyền như thế, mà [thế giới đã] chống lại những

cuộc

dội bom Việt Nam của Hoa Kỳ và, bây giờ, cũng cùng một lý do như vậy,

giúp đỡ

những người Việt tị nạn.

-Có vẻ như vấn đề người Căm

Bốt tị nạn khác với của người Việt tị nạn?

Chuyện xẩy ra ở Căm Bốt là

hoàn toàn quái đản trong lịch sử hiện đại: nhà cầm quyền tàn sát sân

chúng của