|

The

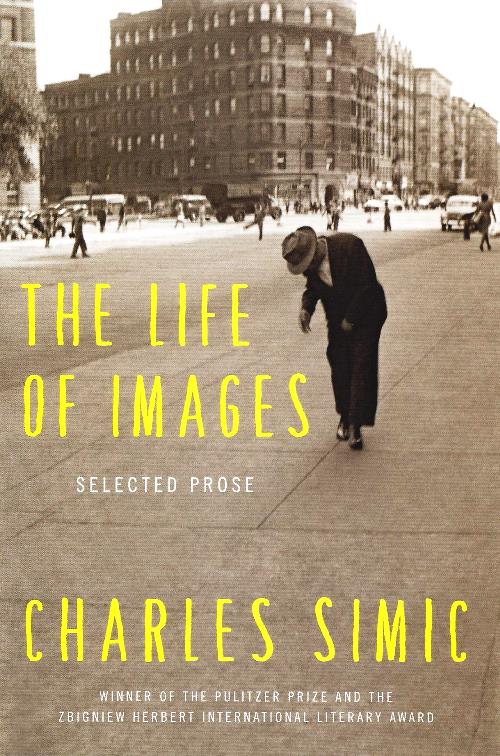

Life of Images

The Life of Images 9 hrs

· Quoc Tru Nguyen I am a writer. It's my job to be alone. Mới đọc 1 câu của Anne Enright. Share with U The

destruction of Vukovar and Sarajevo will not be forgiven the Serbs.

Whatever

moral credit they had as the result of their history they have

squandered in these

two acts. The suicidal and abysmal idiocy of nationalism is revealed

here

better than anywhere else. No human being or group of people has the

right to

pass a death sentence on a city. Nhà thơ thứ thiệt đéo là thành viên của bất cứ bộ lạc nào! On the Couch

with Philip Roth, at the Morgue with Pol Pot Charles

Simic As a rule, I

read and write poetry in bed; philosophy and serious essays sitting

down at my

desk; newspapers and magazines while I eat breakfast or lunch, and

novels while

lying on the couch. It’s toughest to find a good place to read history,

since

what one is reading usually is a story of injustices and atrocities and

wherever one does that, be it in the garden on a fine summer day or

riding a

bus in a city, one feels embarrassed to be so lucky. Perhaps the

waiting room

in a city morgue is the only suitable place to read about Stalin and

Pol Pot? Oddly, the

same is true of comedy. It’s not always easy to find the right spot and

circumstances to allow oneself to laugh freely. I recall attracting

attention

years ago riding to work on the packed New York subway while reading

Joseph

Heller’s Catch 22 and

bursting into guffaws every few minutes. One or

two

passengers smiled back at me while others appeared annoyed by my

behavior. On

the other hand, cackling in the dead of the night in an empty country

house

while reading a biography of W.C. Fields may be thought pretty strange

behavior

too. Wherever and

whatever I read, I have to have a pencil, not a pen—preferably a stub

of a

pencil so I can get close to the words, underline well-turned

sentences,

brilliant or stupid ideas, interesting words and bits of information,

and write

short or elaborate comments in the margins, put question marks, check

marks and

other private notations next to paragraphs that only I—and sometimes

not even

I—can later decipher. I would love to see an anthology of comments and

underlined passages by readers of history books in public libraries,

who

despite the strict prohibition of such activity could not help

themselves and

had to register their complaints about the author of the book or the

direction

in which humanity has been heading for the last few thousand years. Witold

Gombrowicz says somewhere in his diaries that we write not in the name

of some

higher purpose, but to assert our very existence. This is true not only

of

poets and novelists, I think, but also of anyone who feels moved to

deface

pristine pages of books. With that in mind, for someone like me, the

attraction

some people have for the Kindle and other electronic reading devices is

unfathomable. I prefer my Plato dog-eared, my Philip Roth with coffee

stains,

and can’t wait to get my hands on that new volume of poetry by Sharon

Olds I

saw in a bookstore window late last night. December 14, 2009 12:55 p.m. Trên tràng kỷ

với Philip Roth, Như là luật,

tôi đọc thơ ở trên giường; triết và tiểu luận nghiêm túc ngồi trên ghế,

ở nơi bàn

viết; báo chí khi ăn sáng hay trưa, và tiểu thuyết thì nằm dài trên

tràng kỷ.

On the Couch

with Philip Roth, at the Morgue with Pol Pot Charles

Simic As a rule, I

read and write poetry in bed; philosophy and serious essays sitting

down at my

desk; newspapers and magazines while I eat breakfast or lunch, and

novels while

lying on the couch. It’s toughest to find a good place to read history,

since

what one is reading usually is a story of injustices and atrocities and

wherever one does that, be it in the garden on a fine summer day or

riding a

bus in a city, one feels embarrassed to be so lucky. Perhaps the

waiting room

in a city morgue is the only suitable place to read about Stalin and

Pol Pot? Oddly, the

same is true of comedy. It’s not always easy to find the right spot and

circumstances to allow oneself to laugh freely. I recall attracting

attention

years ago riding to work on the packed New York subway while reading

Joseph

Heller’s Catch 22 and

bursting into guffaws every few minutes. One or

two

passengers smiled back at me while others appeared annoyed by my

behavior. On

the other hand, cackling in the dead of the night in an empty country

house

while reading a biography of W.C. Fields may be thought pretty strange

behavior

too. Wherever and

whatever I read, I have to have a pencil, not a pen—preferably a stub

of a

pencil so I can get close to the words, underline well-turned

sentences,

brilliant or stupid ideas, interesting words and bits of information,

and write

short or elaborate comments in the margins, put question marks, check

marks and

other private notations next to paragraphs that only I—and sometimes

not even

I—can later decipher. I would love to see an anthology of comments and

underlined passages by readers of history books in public libraries,

who

despite the strict prohibition of such activity could not help

themselves and

had to register their complaints about the author of the book or the

direction

in which humanity has been heading for the last few thousand years. Witold

Gombrowicz says somewhere in his diaries that we write not in the name

of some

higher purpose, but to assert our very existence. This is true not only

of

poets and novelists, I think, but also of anyone who feels moved to

deface

pristine pages of books. With that in mind, for someone like me, the

attraction

some people have for the Kindle and other electronic reading devices is

unfathomable. I prefer my Plato dog-eared, my Philip Roth with coffee

stains,

and can’t wait to get my hands on that new volume of poetry by Sharon

Olds I

saw in a bookstore window late last night. December 14, 2009 12:55 p.m. Trên tràng kỷ

với Philip Roth, Căng nhất là tìm ra một chỗ thật ngon để đọc lịch sử, bởi vì cái thứ mà bạn đọc đó, thì đầy rẫy những bất công, những điều ghê rợn, và một khi bạn đọc nó, thì có lẽ nên đọc ở ngoài vườn, vào một ngày hè đẹp trời hay là khi đi xe buýt trong thành phố, bạn cảm thấy bực bội, bị làm phiền, nhờ vậy mà thành ra may mắn. Nhưng có lẽ nhà xác của một thành phố là chỗ thật thích hợp để đọc về Stalin và Pol Pot. Lạ lùng làm sao, cũng như vậy, là với hài kịch. Ðâu có dễ mà tìm được đúng chỗ, và hoàn cảnh để tự cho phép mình cười một cách thoải mái, tự do. Tôi lại nhớ cái lần đọc Joseph Heller’s Catch 22 cách đây nhiều năm, khi ngồi trên xe điện ngầm đông người ở New York, trên đường đi làm, và cứ vài phút lại cười hô hố một cách thật là sảng khoái. Một vài hành khách nhìn tôi mỉm cười, trong khi những người khác tỏ ra rất ư là bực bội. Mặt khác, quang quác như gà mái đẻ trong cái chết của một đêm đen, trong một căn nhà ở miền quê, khi đọc tiểu sử W.C. Fields thì tâm thần có vấn đề, hơi bị mát dây, hẳn là như vậy. Ở đâu, đọc, bất cứ cái chi chi, là tôi phải thủ cho mình 1 cây viết chì, không phải viết mực - tốt nhất là một mẩu viết chì, như thế tôi có thể tới thật gần với những chữ, gạch đít những câu kêu như chuông, viết tới chỉ, những ý nghĩ sáng láng, hay, ngu thấy mẹ, những từ thú vị, đáng quân tâm, những mẩu thông tin, và chơi một cái còm ở bên lề trang sách, một cái dấu hỏi, đánh dấu trang, đoạn, đi 1 đường mật mã mà chỉ tôi mới hiểu được, [và có khi, chính tôi cũng chịu thua], như là dấu chỉ đường, nhằm đọc tiếp những trang sau đó. Tôi rất mê đọc một tuyển tập những cái còm, và những đoạn được gạch đít, của những độc giả, trong những cuốn sách lịch sử ở trong thư viện công cộng, đã từng có mặt ở trên trái đất này hàng ngàn năm, mặc dù sự cấm đoán rất ư là chặt chẽ. Witold Gombrowicz có nói đâu đó, trong nhật ký của ông, là chúng ta viết không phải là để nhân danh những mục đích cao cả, nhưng chỉ để khẳng định cái sự hiện hữu rất ư là mình ên của mình. Ðiều này không chỉ đúng với thi sĩ, tiểu thuyết gia, mà còn đúng với bất cứ 1 kẻ nào cảm thấy bị kích thích, chỉ muốn làm xấu đi 1 trang sách cổ xưa. Với ý nghĩ này ở trong đầu, một kẻ như tôi thật không thể chịu nổi cái sự ngu si của người đời, khi bị quyến rũ bởi ba thứ quỉ quái như là sách điện tử, “tân bí kíp” Kindle! Tôi khoái cuốn Plato quăn góc của tôi, cuốn Philip Roth của tôi với những vết cà phe, và nóng lòng chờ đợi cái giây phút cực khoái: được mân mê tuyển tập thơ mới ra lò của Sharon Olds mà tôi nhìn thấy vào lúc thật khuya đêm qua, tại khung kính của 1 tiệm sách. Errata: It’s toughest to find a good

place to

read history, since what one is reading usually is a story of

injustices and

atrocities and wherever one does that, be it in the garden on a fine

summer day

or riding a bus in a city, one feels embarrassed to be so lucky.

Perhaps the

waiting room in a city morgue is the only suitable place to read about

Stalin

and Pol Pot? Căng nhất là

tìm ra một chỗ thật ngon để đọc lịch sử, bởi vì cái thứ mà bạn đọc đó,

thì đầy

rẫy những bất công, những điều ghê rợn, và một khi bạn đọc nó, thì có

lẽ nên đọc

ở ngoài vườn, vào một ngày hè đẹp trời hay là khi đi xe buýt trong

thành phố, bạn

cảm thấy bực bội, bị làm phiền, nhờ vậy mà thành ra may mắn. Nhưng có

lẽ nhà

xác của một thành phố là chỗ thật thích hợp để đọc về Stalin và Pol

Pot. Căng nhất là

tìm ra một chỗ thật ngon để đọc lịch sử, bởi vì cái thứ mà họ đang

đọc

đó thường thường nói về những bất công, những điều ghê rợn,

và

khi người ta đọc nó tại những nơi, hoặc trong một căn vườn vào

một

ngày hạ đẹp hoặc đang trên xe buýt trong một thành phố nào đó, người ta

sẽ cảm

thấy xấu hổ vì mình may mắn quá . Phải chăng phòng đợi của

một nhà

xác thành phố là nơi thích hợp duy nhất để đọc Stalin hay Pol Pot ? Tks Đọc lại, tá hoả.Dịch nhảm thực! Tks again NQT

ELEGY IN A

SPIDER'S WEB In a

letter

to Hannah Arendt, Karl Jaspers describes how the philosopher Spinoza

used to

amuse himself by placing flies in a spider's web, then adding two

spiders so he

could watch them fight over the flies. "Very strange and difficult to

interpret," concludes Jasper. As it turns out, this was the only time

the

otherwise somber philosopher was known to laugh.

I knew he was pulling my leg, but I was shocked nevertheless. I told him that I was never very good at hating, that I've managed to loathe a few individuals here and there, but had never managed to progress to hating whole peoples. "In that case," he replied, "you're missing out on the greatest happiness one can have in life." I’m

surprised that there is no History of Stupidity. I envision a work of

many

volumes, encyclopedic, cumulative, with an index listing millions of

names. I

only have to think about history for a moment or two before I realize

the

absolute necessity of such a book. I do not underestimate the influence

of

religion, nationalism, economics, personal ambition, and even chance on

events,

but the historian who does not admit that men are also fools has not

really

understood his subject.

Watching Yugoslavia dismember itself, for

instance, is like watching a man mutilate himself in public. He has

already

managed to make himself legless, armless, and blind, and now in his

frenzy he's

struggling to tear his heart out with his teeth. Between bites he

shouts to us

that he is a martyr for a holy cause, but we know that he is mad, that

he is

monstrously stupid.

Bi khúc

trong mạng nhện

Trong 1 lá

thư viết cho Hannah Arendt, Karl Jaspers kể, về triết gia Spinoza, giải

khuây bằng

cách bắt mấy con ruồi bỏ vô một cái mạng nhện, và sau đó, bỏ thêm vô

hai con nhện,

và theo dõi hai đấng nhện quần thảo lẫn nhau, tranh giành mồi. "Vậy là mi đánh mất cái hạnh phúc lớn lao nhất mà 1 con người có được ở trên cõi đời này rồi!” Tôi ngạc nhiên,

tại sao không có Lịch Sử của sự Ngu Đần, và bèn mơ tưởng một tác phẩm,

rất nhiều

tập, một bách khoa toàn thư, tích luỹ, thu thập… với

1 index gồm rất nhiều tên. Cứ mỗi lần nghĩ

đến lịch sử, chừng một, hai phút là tôi thèm viết nó, và bèn nhận ra

cái sự cần

thiết của cuốn sách như thế. Tôi không coi thường, đánh giá thấp, ảnh

hưởng của

tôn giáo, chủ nghĩa quốc gia, kinh tế học, tham vọng cá nhân, và ngay

cả cái gọi

là cơ may trong những sự kiện, nhưng một sử gia mà không thừa nhận

rằng, con người

là lũ khùng, thì người đó chưa thấu đáo về cái đề tài của mình.

THE TRUE

ADVENTURES OF FRANZ KAFKA'S CAGE A cage went

in search of a bird. Cái lồng bèn lên đường làm

cách mạng, để tìm con chim.

It occurred

to Chairman Mao one day to find out from his chief of secret police how

many

empty cages there were in China and whether they were being carried

about at

night by suspicious individuals he was not aware of or were they ghosts

of some

of his old party comrades whom he had imprisoned and tortured over the

years? Những cuộc phiêu lưu thực của cái lồng chim

của Kafka

Khác với "Bác Hồ có 1 con chim, hỏi thăm chị Định, để xìn[xin] cái lông", Bác Mao, một bữa, qua Cớm Tẫu báo cáo, biết được con số lồng trống rỗng, bèn ra lệnh điều tra, liệu chúng đã được những phần tử nghi ngờ làm chuyện hồ nghi trong đêm khuya, hay là đó là hồn ma của những cựu đảng viên bị Bác cầm tù, tra tấn dòng dã qua bao năm tháng. "Birdcages of the world, free yourself from filthy birds," shouted the young Peruvian revolutionary as he was being led blindfolded before the firing squad. Vùng lên, hỡi những cái lồng chim trầm luân ở trên thế gian này,"Anh Trỗi la lớn, trước khi bị Ngụy làm thịt. ELEGY IN A

SPIDER'S WEB I knew he was pulling my leg, but I was shocked nevertheless. I told him that I was never very good at hating, that I've managed to loathe a few individuals here and there, but had never managed to progress to hating whole peoples. "In that case," he replied, "you're missing out on the greatest happiness one can have in life." I’m

surprised that there is no History of Stupidity. I envision a work of

many

volumes, encyclopedic, cumulative, with an index listing millions of

names. I

only have to think about history for a moment or two before I realize

the

absolute necessity of such a book. I do not underestimate the influence

of

religion, nationalism, economics, personal ambition, and even chance on

events,

but the historian who does not admit that men are also fools has not

really

understood his subject.

Watching Yugoslavia dismember itself, for

instance, is like watching a man mutilate himself in public. He has

already

managed to make himself legless, armless, and blind, and now in his

frenzy he's

struggling to tear his heart out with his teeth. Between bites he

shouts to us

that he is a martyr for a holy cause, but we know that he is mad, that

he is

monstrously stupid.

Cái từ "chúng

tôi" gây phiền phức, phải chăng, cái từ nhỏ xíu "chúng tôi" (mà

tôi quá ghê tởm, đếch tin cậy, và cấm 1 cá nhân 1 con người xử dụng)

-WITOLD

GOMBROWICZ

What are

you? Americans ask me. I explain that I was born in Belgrade, that I

left when

I was fifteen, that we always thought of ourselves as Yugoslavs, that

for the

last thirty years I have been translating Serbian, Croatian, Slovenian,

and

Macedonian poets into English, that whatever differences I found among

these

people delighted me, that I don't give a shit about any of these

nationalist

leaders and their programs ... * Sacrifice

the children-an old story, pre-Homeric-so that the -ALEKSANDER

WAT The

destruction of Vukovar and Sarajevo will not be forgiven the Serbs.

Whatever

moral credit they had as the result of their history they have

squandered in these

two acts. The suicidal and abysmal idiocy of nationalism is revealed

here

better than anywhere else. No human being or group of people has the

right to

pass a death sentence on a city. Here is

something we can all count on. Sooner or later our tribe always comes

to ask us

to agree to murder. For

that

reason he deserves to be exiled, put to death, and remembered. Mistaken ideas always end

in

bloodshed, but in every case it is "There

are always a lot of people just waiting for a bandwagon to jump on

either for

or against something," Hannah Arendt said in a letter. She knew what

she

was talking about. The terrifying thing about modern intellectuals

everywhere

is that they are always changing idols. At least religious fanatics

stick

mostly to what they believe in. All the rabid nationalists in Eastern

Europe

were Marxists yesterday and Stalinists last week. The freedom of the

individual

has never been their concern. They were after bigger fish. The

sufferings of

the world are an ideal chance for all intellectuals to have an

experience of

tragedy and to fulfill their utopian longings. If in the meantime one

comes to

share the views of some mass murderer, the end justifies the means.

Modern tyrants

have had some of the most illustrious literary salons. So what's to

be done? people rightly ask. I've no idea. As an elegist I mourn and

expect the

worst. Vileness and stupidity always have a rosy future. The world is

still a

few evils short, but they'll come. Dark despair is the only healthy

outlook if

you identify yourself with the flies I as I do. If, however, you

secretly think

of yourself as one of the spiders, or, God forbid, as the laughing

philosopher

himself, you have much less to worry about. Since you'll be on the

winning

side, you can always rewrite history and claim you were a fly. Elegies

in a

spider's web is all we bona fide flies get. That and the beauty of the

sunrise

like some unexpected touch of the executioner's final courtesy the day

they take

us out to be slaughtered. In the meantime, my hope is very modest.

Let’s have a

true ceasefire for once, so the old lady can walk out into the rubble

and find

her cat. Charles Simic: The Life of Images Một tên BVVC của Gấu, một

năm trước đây, mail Gấu, tại làm sao mà mi không về nước mà thù đồng

bào Mít của riêng, của chính mi? ... không thể

có hòa giải với chính quyền cộng sản Việt Nam mà chỉ có thể giải thể

chế độ cộng

sản này đi. Một khi chế độ cộng sản Việt Nam bị giải thể thì tự dưng sẽ

có sự

hòa giải giữa các quan điểm khác nhau. Bởi vì lúc đó, chế độ sẽ là dân

chủ-đa đảng,

ai cũng có quyền nói lên quan điểm của mình, không còn ai bị coi là thù

địch với

ai nữa, mà đó chỉ là sự khác biệt hay đối lập về mặt chính trị mà thôi. Bởi là vì cả hai cuộc chiến dân Mít đều bị lũ Việt Minh, trước, và Bắc Kít, sau, giật giây, xỏ mũi. Đau thế. Thảm thế.

|