TIN VĂN TRÊN

ART2ALL

Album

PB Summer [Al, trang trong]

Note: Tin Văn, Jan

30, 2004 *

Making

America

Tạo Dựng Nước Mỹ

Lucy Carlyle

đọc

lê thi diem thúy

The Gangster

We Are All Looking For.

Tên Găng Tơ Mà Tất Cả Chúng Ta Tìm.

Nhà xb Picador, 160 trang,

12.99 Anh Kim [Anh]

Nhà

xb Knopf [Mỹ], 18 US

Trước khi The Gangster We Are

All Looking For được xb tại Mỹ vào năm 2001, lê thi diem thúy

là một nghệ sĩ trình diễn có tiếng trong giới kịch

nghệ, với những tác phẩm mang tính tư tưởng, tự thuật. Qua

những tác phẩm như Red Fiery Summer và the bodies between us

[hiện đương được chuyển thành tiểu thuyết], bà đào sâu,

khai phá những đề tài như chiến tranh, tính thực dân

đô hộ về văn hóa, hồi ức, và căn cước từng cá nhân

[identity], dựa vào kinh nghiệm trẻ thơ của bà, như là

một cô gái, bị bứng ra khỏi Việt Nam và trồng lại ở Mỹ.

Với The Gangster, bà chuyển những mầy mò khám phá có tính riêng tư, thầm kín,

về những liên hệ giữa Á Châu và Tây Phương,

thành thể văn hư cấu. [The Gangster đã từng xuất hiện trong

“Những tiểu luận hay nhất của Mỹ trong năm 1997”. CTND]

Như tác giả, nhân vật kể chuyện ở trong The Gangster là

một bé gái rời Việt Nam trên một con thuyền cùng

với bố, định cư tại miền nam tiểu bang California ở Mỹ, bà mẹ sau

đó cũng tới đây sống với họ. Cuốn sách dựa trên

kinh nghiệm riêng của thúy, kể những gì xẩy ra sau cuộc

dời đổi – tái định cư, từ một nơi ăn chốn ở không đuợc thoải

mái, tới một nơi ăn chốn ở khác, sự chưng hửng nơi đất lạ,

và nỗi lo sợ tai ương có thể bùng nổ bất cứ lúc

nào, ở trong gia đình, vì những cấu xé, trì

chiết với chính nó.

Bằng con mắt của một bé gái, và của một cái

tôi, một bản ngã, đang phát triển, của một bé

gái tị nạn, thuý chuyển những chi tiết vụn vặt của cuộc sống

tại tiểu bang California ở Mỹ, thành niềm bí ẩn, và

sự ngỡ ngàng.

Chúng

tôi ngồi trước mớ giầy chưng diện, đẹp đẽ, bóng loáng

của Ken, đôi nào đôi nấy mỗi đôi mỗi kiểu, mỗi

đôi mỗi góc, như thể

người mang giầy thì đã tuột ra khỏi, trong khi giầy, do nặng

nề không thể theo, nên bị bỏ lại.

Bằng những kiểu giải thích lầm lạc mang tính

tưởng tượng như thế, nước Mỹ trở thành một cái gì khác

chính nó: không phải Mỹ, không phải Việt Nam,

nhưng mà là một nơi chốn của sự lạng quạng, trật chìa,

trục trặc [a place of dislocation], của xa lạ thái quá, và

của bí ẩn. Nhưng thuý, đẩy sự không thể làm sao

giải thích này, về phía gia đình của mình.

Cô tưởng tượng, những người qua đường đã nhìn như thế

nào về gia đình của cô, nhân một lần đi siêu

thị quá khuya: “Gia đình này chẳng mua sắm gì

hết và rời siêu thị ít phút sau, trước 1 giờ

sáng, sau khi đứa bé, có lẽ là con gái

của họ, nằm giữa lối đi ở khu bán gia vị, trong khi người đàn

ông thì mê mẩn với đủ thứ chai lọ, bao bì đựng

các loại muối ăn.”

Nếu gia đình này làm cho nước Mỹ trở thành

xa lạ, thì cũng có thể nói ngược lại, như thế, nghĩa

là, chính nước Mỹ đã biến những người trong gia đình

này thành những kẻ lạ, trong tiến trình “mày làm

tao sao, thì tao làm mày y hệt như vậy” [a process of

mutual alienation].

Trong khi suy nghĩ về bản chất của sự xa lạ - của cả hai, một bên

là xứ sở thâu nhận họ, và một bên là những

người mới tới - người kể chuyện chuyên chở, không chỉ sự giải

thích cuộc sống Tây Phương, của một người ở bên ngoài

cuộc sống đó, mà còn một hiểu biết thật ngỡ ngàng

của cô, về cha mẹ của mình. Cô để ý, với con mắt

gần như không muốn can thiệp vô, hay xâm phạm tới, sự

kiện, mẹ cô cạo trọc đầu, sau một lần cãi lộn với cha cô,

và sau đó đội một cái nón đánh banh;

hay sự kiện này, trong khi coi phim chưởng, mẹ cô thích

thú ngồi rung đùi, và điều này làm cho

cha cô “như phát khùng”, và sau đó, ngồi

cứng ngắc, bất động suốt cả đêm. Cô con gái tin rằng,

mẹ mình ngày xưa là một người ngoan đạo, còn

cha cô, là một tên găng tơ, nhưng

thực hư ra sao, chẳng làm sao biết.

Một phần, như chúng ta thấy, sự thất bại trong việc hiểu biết lẫn

nhau này, là do sự chẳng hứng thú gì, trong

tình yêu [giữa ông bố và bà mẹ], và

một phần, là do tính bí ẩn của tuổi thơ ấu [the myteriousness

of childhood]. Nhưng có thể còn do sự mất mát hồi ức

vì gia đình bị bứng ra khỏi mảnh đất này, đem tới mảnh

đất khác. Sự nhắc nhở không giải thích tới một người

anh hay em trai đã mất khiến chúng ta có thể nghĩ rằng,

có một sự đứt đoạn về lịch sử, trong khi đó, những phản ứng

lớ ngớ của cha mẹ cô gái về những hoàn cảnh thực tế của

cuộc sống Mỹ, điều này như muốn nói lên sự bất bình,

không muốn nhập vào thời điểm hiện tại, cuộc sống hiện thời.

Chẳng thể sở hữu, cái

đã mất, đã qua, cũng như cái đang có, đang cầm

trong tay, điểm xoáy của câu chuyện kể vì vậy cứ thế

đong đưa giữa quá khứ và hiện tại, và cũng thế là

nhân vật chính, đong đưa giữa thế giới trong nhà, và

thế giới bên ngoài. Cùng lúc….

Và cả hai đứa chúng

tôi đều tin rằng còn nhiều độc giả khác nữa, không

thể quên cái xen anh chàng Tự Học [L' Autodidacte] bị tay quản thủ

thư viện người Corse đánh cho sặc máu mũi, vì cái

tội vẫy gọi nhau làm người, đam mê làm người, say mê

chủ nghĩa nhân bản, trong Buồn Nôn...

- NQT

"Bạn hãy

nói bạn có đọc Sartre không, bạn hãy nói,

bạn có ưa thích Sartre không, tôi sẽ nói

bạn là ai." -

HPA:

Jean-Paul Sartre [trong Những Không Gian & Khoảnh Khắc Văn Chương,

nhà xb Hội Nhà Văn 1999]

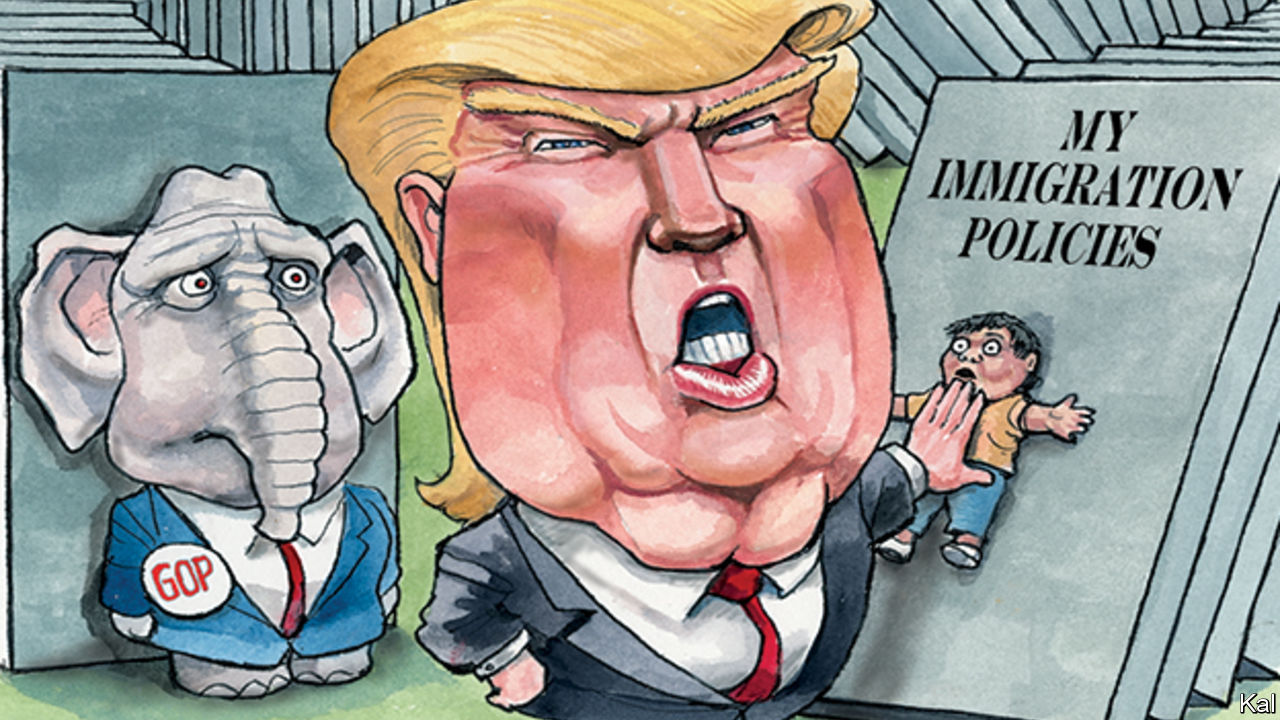

Lexington:

A blot against America

But Donald Trump’s ill-fated policy

of caging children will hurt his party more than him

Nhưng chính sách bịnh hoạn [ill-fated; yểu mệnh] nhốt

trẻ con vô chuồng sẽ làm tổn thương đảng của Trump hơn là

Trump

https://www.economist.com/united-states/2018/06/23/a-blot-against-america

But

Donald Trump’s ill-fated policy of caging children will hurt his party

more than him

Note: Tờ này giật tít, cực độc.

Lần Lú lên đỉnh vinh quang, sau khi nhổ được cái

gai Anh Ba X: Đại Hội của loài bò sát.

Trên Tin Văn có copy bài viết này, để

coi lại, rồi trình độc giả.

Nhưng cái tít này, có thể chôm

Tin Văn, và Tin Văn thì chôm của Améry.

Ông Thánh Lò Thiêu, phán, ta mang

gánh nặng Lò Thiêu, đâu phải cả lò Đức.

(1)

Câu của NKT, The Economist quá dã man,

khi, chính Trump, gốc gác di dân, bị “đất mẹ” tống

đi lưu dầy, vì thành tích bất hảo - nước Úc

được thành lập, là theo kiểu này. Tờ Harper’s khui

vụ này, trên Tin Văn post lại.

Tên Trump đau có đau bằng cả nước Mẽo đau, “được, được!”

[Tờ NKT dùng từ "đảng" của Trump. Gấu tố thêm.]

Ta mang gánh nặng Cái Ác Bắc Kít, đâu

phải lũ Bắc Kít!

Sao mi thù Bắc Kít đến mức khốn nạn như thế, chồng

ta là Bắc Kít… ?

Hà, hà!

Sorry!

(1)

http://tanvien.net/TG_TP/Jean_Amery.html

Moi, je traine le fardeau de la faute collective,

dis-je, pas eux.

Jean Améry viết, trong Vượt quá tội ác và

hình phạt, Par-delà le

crime et le châtiment.

Gấu cũng có thể nói

như thế:

Ta mang cái gánh nặng của Cái Ác Bắc

Kít, đâu phải lũ Bắc Kít?

http://www.nybooks.com/daily/2018/…/20/tales-from-the-gulag/

Kolyma Stories is a collection of short stories inspired by the

fifteen years that Varlam Shalamov (1907–1982) spent as a prisoner in

the Soviet Gulag. Shalamov did six years of slave labor in the gold mines

of Kolyma before gaining a more tolerable position as a paramedic in the

prison camps. He began writing his account of life in Kolyma after Stalin’s

death in 1953.

—The Editors

TRAMPLING THE SNOW

How do you trample a road through virgin snow? One man walks ahead,

sweating and cursing, barely able to put one foot in front of the other,

getting stuck every minute in the deep, porous snow. This man goes a

long way ahead, leaving a trail of uneven black holes. He gets tired,

lies down in the snow, lights a cigarette, and the tobacco smoke forms

a blue cloud over the brilliant white snow. Even when he has moved on,

the smoke cloud still hovers over his resting place. The air is almost

motionless. Roads are always made on calm days, so that human labor is not

swept away by wind. A man makes his own landmarks in this unbounded snowy

waste: a rock, a tall tree. He steers his body through the snow like a

helmsman steering a boat along a river, from one bend to the next.

The narrow, uncertain footprints he leaves are followed by five

or six men walking shoulder to shoulder. They step around the footprints,

not in them. When they reach a point agreed on in advance, they turn around

and walk back so as to trample down this virgin snow where no human foot

has trodden. And so a trail is blazed. People, convoys of sleds, tractors

can use it. If they had walked in single file, there would have been

a barely passable narrow trail, a path, not a road: a series of holes

that would be harder to walk over than virgin snow. The first man has the

hardest job, and when he is completely exhausted, another man from this

pioneer group of five steps forward. Of all the men following the trailblazer,

even the smallest, the weakest must not just follow someone else’s footprints

but must walk a stretch of virgin snow himself. As for riding tractors or

horses, that is the privilege of the bosses, not the underlings.

1956

CONDENSED MILK

Hunger made our envy as dull and feeble as all our other feelings.

We had no strength left for feelings, to search for easier work, to walk,

to ask, to beg. We envied only those we knew, with whom we had come

into this world, if they had managed to get work in the office, the

hospital, or the stables, where there were no long hours of heavy physical

work, which was glorified on the arches over all the gates as a matter

for valor and heroism. In a word, we envied only Shestakov.

Only something external was capable of taking us out of our indifference,

of distracting us from the death that was slowly getting nearer. An external,

not an internal force. Internally, everything was burned out, devastated;

we didn’t care, and we made plans only as far as the next day.

Now, for instance, I wanted to get away to the barracks, lie down

on the bunks, but I was still standing by the doors of the food shop.

The only people allowed to buy things in the shop were those convicted

of nonpolitical crimes, including recidivist thieves who were classified

as “friends of the people.” There was no point in our being there, but

we couldn’t take our eyes off the chocolate-colored loaves of bread; the

heavy, sweet smell of fresh bread teased our nostrils and even made our

heads spin. So I stood there looking at the bread, not knowing when I would

find the strength to go back to the barracks. That was when Shestakov called

me over.

I had gotten to know Shestakov on the mainland, in Moscow’s Butyrki

prison. We were in the same cell. We were acquaintances then, not friends.

When we were in the camps, Shestakov did not work at the mine pit face.

He was a geological engineer, so he was taken on to work as a prospecting

geologist, presumably in the office. The lucky man barely acknowledged

his Moscow acquaintances. We didn’t take offense—God knows what orders

he might have had on that account. Charity begins at home, etc.

“Have a smoke,” Shestakov said as he offered me a piece of newspaper,

tipped some tobacco into it, and lit a match, a real match.

I lit up.

“I need to have a word with you,” said Shestakov.

“With me?”

“Yes.”

We moved behind the barracks and sat on the edge of an old pit

face. My legs immediately felt heavy, while Shestakov cheerfully swung

his nice new government boots—they had a faint whiff of cod-liver oil.

His trousers were rolled up, showing chessboard-patterned socks. I surveyed

Shestakov’s legs with genuine delight and even a certain amount of pride.

At least one man from our cell was not wearing foot bindings instead of

socks. The ground beneath us was shaking from muffled explosions as the

earth was being prepared for the night shift. Small pebbles were falling

with a rustling sound by our feet; they were as gray and inconspicuous as

birds.

“Let’s move a bit farther,” said Shestakov.

“It won’t kill you, no need to be afraid. Your socks won’t be

damaged.”

“I’m not thinking about my socks,” said Shestakov, pointing his

index finger along the line of the horizon. “What’s your view about

all this?”

“We’ll probably die,” I said. That was the last thing I wanted

to think about.

“No, I’m not willing to die.”

“Well?”

“I have a map,” Shestakov said in a wan voice. “I’m going to take

some workmen—I’ll take you—and we’ll go to Black Springs, fifteen kilometers

from here. I’ll have a pass. And we can get to the sea. Are you willing?”

He explained this plan in a hurry, showing no emotion.

“And when we reach the sea? Are we sailing somewhere?”

“That doesn’t matter. The important thing is to make a start.

I can’t go on living like this. ‘Better to die on one’s feet than live

on one’s knees,’” Shestakov pronounced solemnly. “Who said that?”

Very true. The phrase was familiar. But I couldn’t find the strength

to recall who said it and when. I’d forgotten everything in books. I didn’t

believe in bookish things. I rolled up my trousers and showed him my red

sores from scurvy.

“Well, being in the forest will cure that,” said Shestakov, “what

with the berries and the vitamins. I’ll get you out, I know the way.

I have a map.”

I shut my eyes and thought. There were three ways of getting from

here to the sea, and they all involved a journey of five hundred kilometers,

at least. I wouldn’t make it, nor would Shestakov. He wasn’t taking me

as food for the journey, was he? Of course not. But why was he lying? He

knew that just as well as I did. Suddenly I was frightened of Shestakov,

the only one of us who’d managed to get a job that matched his qualifications.

Who fixed him up here, and what had it cost? Anything like that had to

be paid for. With someone else’s blood, someone else’s life.

“I’m willing,” I said, opening my eyes. “Only I’ve got to feed

myself up first.”

“That’s fine, fine. I’ll see you get more food. I’ll bring you

some . . . tinned food. We’ve got lots. . . .”

There are lots of different tinned foods—meat, fish, fruit, vegetables—but

the best of all is milk, condensed milk. Condensed milk doesn’t have

to be mixed with boiling water. You eat it with a spoon, or spread it on

bread, or swallow it drop by drop from the tin, eating it slowly, watching

the bright liquid mass turn yellow with starry little drops of sugar forming

on the can. . . .

“Tomorrow,” I said, gasping with joy, “tinned milk.”

“Fine, fine. Milk.” And Shestakov went off.

I returned to the barracks, lay down, and shut my eyes. It was

hard to think. Thinking was a physical process. For the first time I saw

the full extent of the material nature of our psyche, and I felt

its palpability. Thinking hurt. But thinking had to be done. He was going

to get us to make a run for it and then hand us in: that much was completely

obvious. He would pay for his office job with our blood, my blood. We’d

either be killed at Black Springs, or we’d be brought back alive and given

a new sentence: another fifteen years or so. He must be aware that getting

out of here was impossible. But milk, condensed milk. . . .

I fell asleep and in my spasmodic hungry sleep I dreamed of Shestakov’s

can of condensed milk: a monstrous tin can with a sky-blue label.Enormous,

blue as the night sky, the can had thousands of holes in it and milk

was oozing out and flowing in a broad stream like the Milky Way. And I

had no trouble reaching up to the sky to eat the thick, sweet, starry milk.

I don’t remember what I did that day or how I worked. I was waiting

and waiting for the sun to sink in the west, for the horses to start

neighing, for they were better than people at sensing that the working

day was ending.

The siren rang out hoarsely; I went to the barracks where Shestakov

lived. He was waiting for me on the porch. The pockets of his quilted

jacket were bulging.

We sat at a big, scrubbed table in the barracks, and Shestakov

pulled two cans of condensed milk out of a pocket.

I used the corner of an ax to pierce a hole in one can. A thick

white stream flowed onto the lid and onto my hand.

“You should have made two holes. To let the air in,” said Shestakov.

“Doesn’t matter,” I said, licking my sweet dirty fingers.

“Give us a spoon,” Shestakov asked, turning to the workmen who

were standing around us. Ten shiny, well-licked spoons were stretched

over the table. They were all standing to watch me eat. That wasn’t for

lack of tact or out of any hidden desire to help themselves. None of them

even hoped that I would share this milk with them. That would have been unprecedented;

any interest in what someone else was eating was selfless. I also knew

that it was impossible not to look at food disappearing into someone else’s

mouth. I made myself as comfortable as I could and consumed the milk without

bread, just washing it down occasionally with cold water. I finished the

two cans. The spectators moved away; the show was over. Shestakov looked

at me with sympathy.

“You know what,” I said, carefully licking the spoon. “I’ve changed

my mind. You can leave without me.”

Shestakov understood me and walked out without saying a thing.

This was, of course, a petty revenge, as weak as my feelings.

But what else could I have done? I couldn’t warn the others: I didn’t

know them. But I should have warned them: Shestakov had managed to persuade

five others. A week later they ran off; two were killed not far from Black

Springs, three were tried a month later. Shestakov’s own case was set

aside in the process, and he was soon moved away somewhere. I met him

at another mine six months later. He didn’t get an additional sentence

for escaping. The authorities had used him but had kept to the rules.

Things might have been different.

He was working as a geological prospector, he was clean-shaven

and well-fed, and his chess-pattern socks were still intact. He didn’t

greet me when he saw me, which was a pity. Two tins of condensed milk

was not really worth making a fuss about, after all.

1956

—translated by Donald Rayfield

Gignoux: The Siberian Gulag, 1931

Before our human dream (or terror) wove

Mythologies, cosmogonies, and love,

Before time coined its substance into days,

The sea, the always sea, existed: was.

Who is the sea? Who is that violent being,

Violent and ancient, who gnaws the foundations,

Of earth? He is both one and many oceans;

He is abyss and splendor, chance and wind.

Who looks on the sea, sees it the first time,

Every time, with the wonder distilled

From elementary things-from beautiful

Evenings, the moon, the leap of a bonfire.

Who is the sea, and who am I? The day

That follows my last agony shall say.

[ Trans. John Updike]

I think this poem should be good since the subject is the sea.

The sea has been haunting poetry ever since Homer, and in English poetry

the sea has been there since earliest times. You find it in the first

verses of Beowulf, when we are told of the ship of Scyld, the king of Denmark.

Then they sent him out to sea in a ship. Then the writer says they sent

him to travel far on the power of the sea. And the sea has been always with

us. The sea is far more mysterious than the earth. And I don't think you

can speak of the sea without the memory of that first chapter of Moby Dick.

Therein he felt the mystery of the sea. What have I done? I have merely tried

to rewrite those ancient poems about the sea. I think back to Carnoes of

course-Por mares nunca de antes navegades "O seas never sailed before"-to

The Odyssey, to ever so many seas. The sea is haunting us all the time. It

is still mysterious to us. We do not know what it is or, as I say in the

poem, who he is, since we do not know who we are. That is another mystery.

I have written many poems about the sea. This one may perhaps be worth your

attention. I don't think I can say anything more, since this poem is not

intellectual. That's all to the good. This poem arises from emotion, so

it shouldn't be too bad.

1904: London

THE OLD MEN ADMIRING

THEMSELVES IN THE WATER

I heard the old, old men say,

"Everything alters,

And one by one we drop away."

They had hands like claws, and their knees

Were twisted like the old thorn-trees

By the waters.

I heard the old, old men say,

"All that's beautiful drifts away

Like the waters."

William Butler Yeats, from In the Seven Woods. The Irish poet

was in his thirties when he wrote

this short verse, though it was not, even then, his earliest

work concerned with growing older. 'My first denunciation of old age,"

he later wrote to Olivia Shakes pear, came "before I was twenty." In 1922,

when the Irish Free State was founded, Yeats accepted an invitation to

serve in its senate. The following year he was awarded the Nobel Prize

in Literature.

http://tanvien.net/Viet/rain.html

THE RAIN

When my older brother

came back from war

he had on his forehead a little silver star

and under the star

an abyss

a splinter of shrapnel

hit him at Verdun

or perhaps at Grunwald

(he'd forgotten the details)

He used to talk much

In many languages

But he liked most of all

The language of history

until losing breath

he commanded his dead pals to run

Roland Kowalski Hannibal

he shouted

that this was the last crusade

that Carthage soon would fall

and then sobbing confessed

that Napoleon did not like him

we looked at him

getting paler and paler

abandoned by his senses

he turned slowly into a monument

into musical shells of ears

entered a stone forest

and the skin of his face

was secured

with the blind dry

buttons of eyes

nothing was left him

but touch

what stories

he told with his hands

in the right he had romances

in the left soldier's memories

they took my brother

and carried him out of town

he returns every fall

slim and very quiet

he does not want to come in

he knocks at the window for me

we walk together in the streets

and he recites to me

improbable tales

touching my face

with blind fingers of rain

Zbigniew Herbert: The Collected Poems 1956-1998

Mưa

Khi ông anh của tớ từ mặt

trận trở về

Trán của anh có 1 ngôi sao bạc nho nhỏ

Và bên dưới ngôi sao

Một vực thẳm

Một mảnh bom

Đụng anh ở Plê Ku

Hay, có lẽ, ở Củ Chi

(Anh quên những chi tiết)

Anh trở thành nói

nhiều

Trong nhiều ngôn ngữ

Nhưng anh thích nhất trong tất cả

Ngôn ngữ lịch sử

Đến hụt hơi,

Anh ra lệnh đồng ngũ đã chết, chạy

Nào anh Núp,

Nào anh Trỗi.

Anh la lớn

Trận đánh này sẽ là trận chiến thần thánh

chót

[Mỹ Kút, Ngụy Nhào, còn kẻ thù

nào nữa đâu?]

Rằng Xề Gòn sẽ vấp ngã,

Sẽ biến thành Biển Máu

Và rồi, xụt xùi, anh thú nhận

Bác Hồ, lũ VC Bắc Kít đếch ưa anh.

[Hà, hà!]

Chúng tôi nhìn

anh

Ngày càng xanh mướt, tái nhợt

Cảm giác bỏ chạy anh

Và anh lần lần trở thành 1 đài tưởng niệm

liệt sĩ

Trở thành những cái

vỏ sò âm nhạc của những cái tai

Đi vô khu rừng đá

Và da mặt anh

Thì được bảo đảm bằng những cái núm mắt

khô, mù

Anh chẳng còn gì

Ngoại trừ xúc giác

Những câu chuyện gì,

anh kể

Với những bàn tay của mình.

Bên phải, những câu chuyện tình

Bên trái, hồi ức Anh Phỏng Giái

Chúng mang ông anh

của tớ đi

Đưa ra khỏi thành phố

Mỗi mùa thu anh trở về

Ngày càng ốm nhom, mỏng dính

Anh không muốn vô nhà

Và đến cửa sổ phòng tớ gõ

Hai anh em đi bộ trong

những con phố Xề Gòn

Và anh kể cho tớ nghe

Những câu chuyện chẳng đâu vào đâu

Và sờ mặt thằng em trai của anh

Với những ngón tay mù,

Của mưa

Zbigniew Herbert

(1924-1998)

Born in Lvov, a city that after 1945 was incorporated into

the Soviet Union, Zbigniew Herbert led a difficult life of an eternal

and itinerant student until 1956, when his first collection of poems finally

appeared. As a young man, he hesitated between poetry, art history, and

philosophy. His life remained peripatetic even after 1956, an important

year for Poland as it marked the end to the excesses of Stalinist cultural

policy. Herbert lived then in Warsaw, Paris, Berlin, Italy, and the United

States (he taught for a year at the University of California, Los Angeles).

He was driven to travel by his immense appetite for the ancient and modern

beauty that is scattered throughout the museums, architecture, and landscapes

of western and southern Europe, food for his imagination. Herbert invented

a new tone in poetry, a music filled with tragedy, irony, and goodness. His

"Mr. Cogito," the speaker in many of his poems, is a brilliant and sometimes

melancholy commentator on twentieth-century madness. Herbert's poems turned

out to be readily translatable, so he found a home for his brilliance in

other languages as well (especially in English, German, and Swedish). Still,

he never enjoyed a Goethean peace of mind, tormented by sickness and bad

luck, he became a beloved and nationally worshipped poet only posthumously.

Henryk Elzenberg, one of young Herbert's masters, is the addressee in letters

that follow. Elzenberg was an independent philosopher and a sage.

Adam Zagajewski: Polish writers on writing

Ba Lan Tam Kiệt - Szymborska, Milosz, Herbert - hai đấng

được Nobel, trong khi Herbert, bảnh nhất, lại không được. Cái

gì làm ông quá cả… Nobel?

Theo GCC, thơ của Herbert vượt được ngưỡng Nobel. Đọc AZ phán

về ông, là nhận ra. Còn điều này, Herbert chưa

từng phải bỏ nước ra đi, như Szymsborka, nhưng hơn cả Szymborka, ông

chưa hề 1 lần bị cái bả CS quyến rũ. Khó lắm đấy, cú

này, theo GCC.

Sinh ở Lvov, thành phố sau 1945 bị nhập vào Liên

Xô, Herbert sống cuộc đời khó khăn của 1 sinh viên.

“miên viễn, và lưu động”, cho tới năm 1956, khi tuyển tập

thơ đầu tiên của ông, sau cùng xuất hiện. Khi

còn trẻ, ông lưỡng lự giữa thơ, lịch sử nghệ thuật và

triết học. Đời của ông là 1 đời tiêu dao, ngay cả sau

1956, 1 năm quan trọng đối với Ba Lan, vì nó đánh

dấu chấm hết sự thái quá của chính sách văn

hóa Xì ta lin nít. Herbert từ đó sống ở Warsaw,

Paris, Berlin, Italy, và Mẽo (ông dạy 1 năm ở Đại Học California,

Los Angeles). Ông mê du lịch, bởi nỗi thèm thuồng bao

la của mình, bởi cái đẹp cổ đại và hiện đại rải rác

dàn trải qua những viện bảo tàng, kiến trúc, và

phong cảnh của Tây Âu, Nam Âu, thức ăn của sự tưởng

tượng của ông

Herbert phịa ra 1 giọng mới cho thơ, 1 âm nhạc tẩm đẫm bi kịch,

hài hước, và cái tốt. Mr. Cogito, phát ngôn

viên trong nhiều bài thơ của ông, là 1 tay “còm”

thông minh, sáng chói, và đôi lúc

buồn bã, về cái điên khùng của thế kỷ 20. Thơ

của Herbert, hóa ra là luôn sẵn sàng để được dịch,

vì thế ông còn kiếm ra nhà, cho cái sự

thông minh sáng rỡ của mình, ở trong những ngôn

ngữ khác, (đặc biệt là trong tiếng Anh, Đức. và Thụy

Điển). Tuy nhiên, ông không làm sao enjoy 1 sự bình

an trong tâm hồn theo kiểu của Goethe, (do bị) dằn vặt, bởi bịnh hoạn

và vận xấu, ông trở thành một nhà thơ được yêu

mến và được thế giới ngưỡng vọng, chỉ sau khi chết.

AZ, người biện tập tuyển tập Những nhà văn Balan bàn về

viết, thay vì giới thiệu thơ Herbert, thì là những thư

từ trao đổi giữa Herbert và người nhận thư, Henryk Elzenberg, là

1 trong những sư phụ trẻ của trường phái Herbert, một triết gia độc

lập và hiền giả

Tin Văn post 1 đoạn, trong 1 cuộc trò chuyện, giữa hai tác

giả trên, và, có thể, khi đọc, chúng ta mường

tượng ra câu trả lời của TTT, khi ông không "viết lại,

lại viết", re-écrire.

RG: Could you define your poetry in one sentence?

ZH: When a person decides to take the frightening step of publishing,

he has no idea what the consequences will be for his life, for his health.

Writing, painting (I might not include music) leave

their mark on the soul. They make it either better or worse, but never

leave it indifferent. Here my younger colleagues will say: "He's all right,

he got prizes, he's sitting in Paris and giving us advice." Nevertheless

it is choosing danger, choosing fate, a more difficult life. I would

like what I write to be the reflection of some human life- unimportant,

undistinguished, mine - and through that the life of my generation, my relation

to my elders, to my masters. That is a duty of continuity and - apart from

my terrible character flaws - a duty of fidelity. Oh, that's what I would

say, that my poetry is about fidelity; in general it is about a certain virtue

of endurance, of affirming life in all its complexity. And I still hope that

one day when I see that I'm slipping on the page, I will have the courage

to say to myself: "No thanks, I step down." There's that eternal question

of Mauriac's: why did Rimbaud stop writing? Well, because he had said everything.

Translated by Alissa Valles

Well, because he had said everything.

Đặng Tiến, khi viết về TTT, dùng chữ tiết tháo. Herbert,

dùng chữ trung thực, fidelity, a certain virtue of endurance, of

accepting life…

Note: Bài tưởng niệm Herbert của Hass, cũng thật tuyệt. Nhưng

bài tuyệt nhất, là bài giới thiệu tuyển tập thơ Herbert,

của AZ, theo GCC

AUGUST 16 [1998]

In Memoriam: Zbigniew Herbert

Zbigniew Herbert

died a few weeks ago in Warsaw at the age of seventy-three. He is one of

the most influential European poets of the last half century, and perhaps-even

more than his great contemporaries Czeslaw Milosz and Wladislawa Szymborska-the

defining Polish poet of the post-war years.

It's hard to know how to talk about him, because

he requires superlatives and he despised superlatives. He was born in Lvov

in 1924. At fifteen, after the German invasion of Poland, he joined an underground

military unit. For the ten years after the war when control of literature

in the Polish Stalinist regime was most intense, he wrote his poems, as

he said, "for the drawer." His first book appeared in 1956. His tactic, as

Joseph Brodsky has said, was to turn down the temperature of language until

it burned like an iron fence in winter. His verse is spare, supple, clear,

ironic. At a time when the imagination was, as he wrote, "like stretcher bearers

lost in the fog," this voice seemed especially sane, skeptical, and adamant.

He was also a master of the prose poem. Here are some samples:

Zbigniew

Herbert mất vài tuần trước đây, ở Warsaw thọ 73 tuổi. Ông

là 1 trong những nhà thơ Âu Châu, ảnh hưởng nhất

trong nửa thế kỷ, và có lẽ - bảnh hơn nhiều, so với ngay cả

hai người vĩ đại, đã từng được Nobel, đồng thời, đồng hương với ông,

là Czeslaw Milosz và Wladislawa Szymborska - nhà

thơ định nghĩa thơ Ba Lan hậu chiến.

Thật khó mà biết làm thế nào nói

về ông, bởi là vì ông đòi hỏi sự thần sầu,

trong khi lại ghét sự thần sầu. Ông sinh tại Lvov năm 1924. Mười

lăm tuổi, khi Đức xâm lăng Ba Lan, ông gia nhập đạo quân

kháng chiến. Trong 10 năm, sau chiến tranh, khi chế độ Xì Ta

Lin Ba Lan kìm kẹp văn chương tới chỉ, ông làm thơ, thứ

thơ mà ông nói, “để trong ngăn kéo”. Cuốn đầu tiên của ông, xb năm 1956.

Đòn của ông [his tactic], như Brodsky chỉ cho thấy, là

giảm nhiệt độ ngôn ngữ tới khi nó cháy đỏ như một mảnh

hàng rào sắt, trong mùa đông. Câu thơ

của ông thì thanh đạm, mềm mại, sáng sủa, tếu tếu.

Tới cái lúc, khi mà tưởng tượng, như ông viết,

“như những người khiêng băng ca – trong khi tản thương, [“sơ tán

cái con mẹ gì đó”, hà hà] - mất tích trong sương mù”, thì

tiếng thơ khi đó, mới đặc dị trong lành, mới bi quan, và

mới sắt đá làm sao.Ông

còn là 1 sư phụ của thơ xuôi.

This poetry is about the pain

of the twentieth century, about accepting the cruelty of an inhuman age,

about an extraordinary sense of reality.

And the fact that at the same time the poet loses none of his lyricism

or his sense of humor-this is the unfathomable secret of a great artist.

Thơ này là về nỗi

đau của thế kỷ 20, về chấp nhận cái sự độc ác, tàn bạo,

dã man của thời phi nhân, về cảm quan cực kỳ khác thường

về thực tại. Nhưng, sự kiện, cùng lúc, nhà thơ không

mất đi 1 tí gì của chất trữ tình, hay cái cảm

quan cà chớn, tếu táo, tưng tửng của mình – thì

đó là cái bí mật khủng ơi là khủng của

1 đại nghệ sĩ.

Adam Zagajewski: Introduction

(Translated

by Bill Johnston) (1)

Wislawa Szymborska, a Nobel Prize-winning poet who used the imagery of

everyday objects and a mordant style to explore dramatic themes of human

experience including love, war and death, died Feb. 1 at her home in Krakow,

Poland. She was 88.

Ms. Szymborska shunned the idea of being a political poet, though she

recognized the personal could bleed into the political while living under

a communist regime.

“When I was young, I had a moment of believing in the communist doctrine,”

she told Hirsch in 1996. “I wanted to save the world through communism. Quite

soon, I understood that it doesn’t work, but I’ve never pretended it didn’t

happen to me.

“At the very beginning of my creative life, I loved humanity,” she continued.

“I wanted to do something good for mankind. Soon, I understood that it isn’t

possible to save mankind. There’s no need to love humanity, but there is

a need to like people. Not love, just like. This is the lesson I draw from

the difficult experiences of my youth.”

Nữ thi sĩ Wislawa Szymborska, Nobel văn chương, mất, thọ 88 tuổi. Bà

thường sử dụng hình ảnh những vật dụng đời thường để khai phá

những đề tài thê lương của cõi người, bao gồm tình

yêu, chiến tranh, cái chết. Bà không nghĩ, bà

là nhà thơ chính trị, tuy nhiên theo bà,

chạy trời không khỏi nắng, khi sống dưới chế độ CS.

Khi tôi còn trẻ, đã có lúc tôi

tin vào chủ nghĩa khốn nạn đó, bà nói với thi

sĩ Mẽo Hirsch, vào năm 1966. Tôi muốn kíu thế giới, qua

chủ nghĩa CS. Chẳng mấy chốc tôi nhận ra, vô phương, nhưng tôi

hề chối, đã từng ngu như thế, hà, hà!

Vào lúc rất ư khởi đầu của cái việc viết lách

của tôi, tôi iêu nhân loại, tôi muốn làm

1 điều gì tốt cho nhân loại. Chẳng bao lâu, tôi

nhận ra vô phương kíu nhân loại, và chẳng có

cái yêu cầu iêu nhân loại, nhưng có yêu

kầu, thik nhân noại.

Không phải yêu, mà thik, like, hà, hà!

Chủ nghĩa CS ở xứ Mít theo GCC, không mắc mớ gì tới

chủ nghĩa CS, như những triết gia được coi là những nhà Mác

Học, như Lukacs, Henri Lefebvre, hay Althusser… nghĩ về nó, sống chết

vì nó. Ở Việt Nam, chỉ có mỗi một thằng cha Gấu rất

rành về nó, ngay từ khi vừa mới lớn, là đã đắm

đuối với nó. Đó là sự thực. Gấu chẳng đã từng

kể, thời gian bị VC cho xơi hai trái mìn claymore, ở nhà

hàng nổi Mỹ Cảnh, 1965, trong những giờ phút mấp mé bờ

tử sinh, nơi nhà thương Grall, cuốn sách gối đầu giường của

Gấu là cuốn viết về chủ nghĩa duy vật, cuốn của Henri Lefebvre!

TTT, ông anh của GCC, người được coi là rất rành Mác

Xít, cũng biết 1 thứ Mác Xít qua Raymond Aron, ông

này, triết gia Mác Xít, nhưng không phải là

1 Mác Học, theo GCC.

Phải viết dài dòng như thế, thì bạn đọc mới hiểu,

phát giác khủng khiếp mà Gấu có được, khi đọc

Tolstaya, "Những Thời Ăn Thịt Người", khi vừa đến Trại Tị Nạn Thái

Lan:

Chủ nghĩa CS ở xứ Mít, là quái thai sinh ra từ Cái

Ác Bắc Kít, không mắc mớ gì tới chủ nghĩa CS.

Có thể nói, từ lúc ra đời, 1945, Vẹm, nhập thân

của Cái Ác Bắc Kít, sử dụng bất cứ 1 thứ khi giới nào

tiện dụng, hữu dụng, đối với chúng, để chiếm lấy xứ Mít, làm

của riêng của chúng. Giết sạch những kẻ không theo ta,

vu cho chúng đủ thứ tội ác, nào Việt Gian, tức theo

Tẩy, nào Đệ Tứ, nào Ngụy, theo Mẽo, cốt sao chiếm được cả nước

Mít, chỉ cho chúng!

Tình trạng lúc này, cả nước chống lại chúng,

thì chúng bèn coi cả nước là kẻ thù, cũng

phịa ra đủ thứ tội giáng lên dân Mít, y chang lúc

khởi thuỷ!

Vào thời net, với những phương tiện thông tin tối tân

như You Tube, FB, không có cách chi để bịp bợm, chúng

nói thẳng băng, chúng ông là như thế đó.

Tên Trọng Lú không thèm giấu giếm, Luật An Ninh,

là để bảo vệ chế độ!

Jun 18 at 9:59 AM

nguyên nhân

những con bồ câu. đứng đợi

mẩu bánh mì. được ném. xuống

trời chiều. vàng lụa. đôi mắt. cong

những giọt máu. của đứa con. gái

nhỏ xuống. từ ngón tay. tự cắt

chuyện. từ những ngày. xa xưa

ăn nói. ngớ. ngẩn

tự móc họng. cho ói. mửa

hết những. chất độc

rồi tự bịt kín. mũi

để không phải. hít. thở

cuộc sống. nhiễm độc

từ loài. người

bằng lòng độc. ác

và bằng. sự thông minh

Đài Sử

Bài thơ dưới đây, Gấu đọc lần đầu, cũng lâu lắm

rồi, nay thấy trong cuốn thơ mới mua, tại 1 tiệm sách cũ mới kiếm

thấy, và cũng cảm thấy, như lần đầu đọc: Bài thơ tả cảnh

Gấu trở lại Quán Chùa…

Cafe

Of those at the table in the cafe

where on winter noons a garden of frost glittered on windowpanes

I alone survived.

I could go in there if I wanted to

and drumming my fingers in a chilly void

convoke shadows.

With disbelief I touch the cold marble,

with disbelief I touch my own hand.

It-is, and I-am in ever novel becoming,

while they are locked forever and ever

in their last word, their last glance,

and as remote as Emperor Valentinian

or the chiefs of the Massagetes, about whom I know nothing,

though hardly one year has passed, or two or three.

I may still cut trees in the woods of the far north,

I may speak from a platform or shoot a film

using techniques they never heard of.

I may learn the taste of fruits from ocean islands

and be photographed in attire from the second half of the century.

But they are forever like busts in frock coats and jabots

in some monstrous encyclopedia.

Sometimes when the evening aurora paints the roofs in a poor street

and r contemplate the sky, I see in the white clouds

a table wobhling. The waiter whirls with his tray

and they look at me with a burst of laughter

for I still don't know what it is to die at the hand of man,

they know-they know it well.

Warsaw, 1944

Bài thơ sau đây, trong Wallace Stevens: Selected Poems.

Đấng này, Gấu tìm đọc nhân nghe lời xúi của

bà Thụy Khê Yankee mũi lõ, Helen Vendler!

II

THE WORLD IS LARGER IN SUMMER

He left half a shoulder and half a head

To recognize him in after time.

These marbles lay weathering in the grass

When the summer was over, when the change

Of summer and of the sun, the life

Of summer and of the sun, were gone.

He had said that everything possessed

The power to transform itself, or else,

And what meant more, to be transformed.

He discovered the colors of the moon

In a single spruce, when, suddenly,

The tree stood dazzling in the air

And blue broke on him from the sun,

A bullioned blue, a blue abulge,

Like daylight, with time's bellishings,

And sensuous summer stood full-height.

The master of the spruce, himself,

Became transformed. But his mastery

Left only the fragments found in the grass,

From his project, as finally magnified.

http://www.tanvien.net/new_daily_poetry/Wallace_Stevens.html

THE POEM THAT TOOK THE PLACE OF

A MOUNTAIN

There it was,

word for word,

The poem that

took the place of a mountain.

He breathed its

oxygen,

Even when the

book lay turned in the dust of his table.

It reminded him

how he had needed

A place to go

to in his own direction,

How he had recomposed

the pines,

Shifted the rocks

and picked his way among clouds,

For the outlook

that would be right,

Where he would

be complete in an unexplained completion:

The exact rock

where his inexactnesses

Would discover,

at last, the view toward which they had edged,

Where he could

lie and, gazing down at the sea,

Recognize his

unique and solitary home.

Bài thơ chiếm trái

núi

[Dịch] theo kiểu dùi

đục chấm mắm cáy, “mô tà mô”

[mot-à-mot, word for word]

Thì đúng

là, bài thơ đá đít trái

núi, và chiếm chỗ của nó.

Nó thở không

khí của trái núi

Ngay cả khi cuốn sách

ở trên bàn biến thành bụi

Nó nhắc nhở,

bài thơ cần, ra làm sao, như thế nào

Một nơi chốn để đi,

theo cái hướng của riêng nó

Như thế nào,

nó tái cấu trúc những ngọn thông

Bầy biện lại những

hòn đá, và kiếm ra con đường đi của

nó, giữa những đám mây

Viễn cảnh mà

nói, thì OK

Một khi mà nó

hoàn thiện, trong cái hoàn thiện

không thể nào giải thích được

Đúng cục đá,

khi cái không đúng của nó

Sẽ khám phá,

vào lúc sau cùng, cái nhìn

mà theo đó, chúng xen vô

Nơi nó sẽ nằm,

và nhìn xuống biển

Nhận ra căn nhà

độc nhất, cô đơn của nó.

Note: Bài thơ

thần sầu, tuyệt cú mèo.

Gấu dịch hơi bị nhảm,

nhưng "có còn hơn không", hà,

hà!

Thơ Wallace Stevens, quả là quái. Gấu nhớ, có

dịch mấy bài, cực thú vị, nhưng kiếm không ra.

Bài Người Tuyết, Snow Man được tác giả cuốn Thơ Kíu

đời lôi ra, (1) khen um lên, trên Tin Văn cũng có

dịch, nhưng Gấu đọc, không vô.

Cách vị này giải thích bài "Dừng ngựa

bên rừng chiều tuyết phủ", theo Gấu, thua cách của Borges,

và của đám UNHCR hiểu, khi dùng bài thơ này,

như là 1 nhắn nhủ lũ Mít lưu vong:

Tụi mi có những lời hứa phải giữ, promises to keep, trước khi

lăn ra ngủ [ngỏm]

(1)

Poetry will save your life, by Jill Bialosky,

a memoir

Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village, though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

My little horse must think it queer

To stop without a farmhouse near

Between the woods and frozen lake

The darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound's the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep

Robert Frost

~~oOo~~

Dừng ngựa bên rừng buổi

chiều tuyết rụng

Rừng này của ai tôi nghĩ tôi biết

Nhà ông ta ở trong làng

Làm sao ông ta thấy tôi ngừng ngựa

Ngắm tuyết rơi phủ kín rừng.

Ngựa của tôi chắc thấy kỳ kỳ

Tại sao ngưng ở đây, chung quanh chẳng nhà cửa trang

trại,

Chỉ thấy rừng và hồ nước đóng băng

Vào đúng chiều hôm cuối năm

Nó bèn khẩy khẩy cái chuông nhỏ

Như để nói với chủ của nó, này, chắc có

chi lầm lẫn

Để đáp lại tiếng chuông ngựa,

Là tiếng gió thoảng và tiếng mỏng của hạt

tuyết rơi.

Rừng thì đẹp, tối, và sâu

Nhưng tôi còn những lời hứa phải giữ

Và nhiều dặm đường phải đi

Trước khi lăn ra ngủ

Lăn ra ngủ

Nguyễn Quốc Trụ dịch

Trong cuốn sách của những điều sáng

rỡ, Milosz chọn được “nhõn” 1 bài thơ của Wallace Stevens.

Tuy nhiên, theo Gấu, cách đọc Stevens của Milosz, không…

tới. Stevens có nhiều bài thơ phải nói là thần

sầu, thí dụ bài A Child Asleep In Its

Own Life, Tin Văn đã từng giới thiệu, nhưng kiếm không

ra. Bài Snow Man mà chẳng tuyệt sao.

WALLACE STEVENS

1879-1955

Wallace Stevens was under the spell of science and scientific methods.

An analytical tendency is visible in his poems on reality, and this is just

opposite to the advice of Zen poet Basho, who wanted to capture the thing

in a single stroke. When Stevens tries to describe two pears, as if for

an inhabitant of another planet, he enumerates one after another their chief

qualities, making his analysis akin to a Cubist painting. But pears prove

to be impossible to describe.

Czeslaw Milosz: A Book of Luminous Things

Tạm dịch: Stevens ăn phải bả của khoa học và những phương pháp

khoa học. Trong những bài thơ về thực tại, rõ ràng

nhận ra, khuynh huớng nghiên cứu, và điều này ngược

hẳn lại với Basho, bắn 1 phát là trúng ngay con mồi!

Khi Stevens cố gắng miêu tả hai trái đào tiên,

cho một kẻ chưa từng tới Thiên Thai, ông lèm bèm

hết cái con ngon tới cái ngon khác của hai trái

đào tiên, y chang trường phái Lập Thể.

Nhưng đào tiên thì làm sao mà miêu

tả?

Nếu có, thì đành bắt chước Basho, đợp 1 phát!

Hà, hà!

STUDY OF TWO PEARS

1

Opusculum paedagogum.

The pears are not viols,

Nudes or bottles.

They resemble nothing else.

2

They are yellow forms

Composed of curves

Bulging toward the base.

They are touched red.

They are not flat surfaces

Having curved outlines.

They are round

Tapering toward the top.

4

In the way they are modelled

There are bits of blue.

A hard dry leaf hangs

From the stem.

5

The yellow glistens.

It glistens with various yellows,

Citrons, oranges and greens

Flowering over the skin.

6

The shadows of the pears

Are blobs on the green cloth.

The pears are not seen

As the observer wills.

Poetry is the scholar's art."

Wallace Stevens, Opus Posthumous

Thơ là nghệ thuật khoa bảng

Cole: You said you don’t often do negative reviews. What do you do with

a book you don’t like? How do you handle it?

Vendler: I forget it-you mean if I have to write about it?

Cole: Yes.

Vendler: I tell the truth as I see it. I was reading a biography of

Mary McCarthy, and it turns out she was hurt by a review that I did of

her Birds of America. But she also believed it to be true, which hurt her

more.

Cole: As a writer and a professor, I guess I understand both sides of

the equation. This has been interesting. Thank you for taking time out

from your academic schedule.

Vendler: Thank you.

[Bà nói, bà không viết nhiều, cái

thứ điểm sách tiêu cực - tức chê bai, mạ lị, miệt thị…

như GCC thường viết – Bà làm gì với cuốn bà

không thích? Làm thế nào bà “handle”

nó?

Bạn tính nói, nếu tôi phải viết về nó?

Yes

Thì cứ nói thẳng ra ở đây. Tôi đọc tiểu sử

của Mary McCarthy, hóa ra là bà bị tui, chính

tui, phạng cho 1 cú đau điếng, khi điểm cuốn "Chim Mẽo" của bà.

Nhưng bà cũng nói thêm, tui phạng đúng, và

cái đó làm bà còn đau hơn nhiều!]

Ui chao, GCC đã từng gặp đúng

như thế, khi phạng nhà thơ NS. Ông đau tới chết, như

1 bạn văn nhận xét, “anh đâm trúng tim của ông

ta, nhà văn nhà thơ dễ dãi và sung sướng và

hạnh phúc”!

Cú đánh NTH mà chẳng thú sao!

“Văn chương khủng khiếp”!

Hà, hà!

Đúng là 1 tên

“sa đích văn nghệ”, như NS gọi GCC!

The Incomparable Critic

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2015/aug/13/helen-vendler-incomparable-critic/

Charles Simic

Nostalgia

When the cobbler shop closed in our village

with a hand-written note in the window

and an apology

on a wintry evening,

while crows sat with big shoulders,

their backs turned in the last shiver of light,

I was driven

not to elegy but etymology:

Ceapail perhaps, meaning binding or fettering?

Klabba from the Swedish?

More likely cobolere, to mend shoes.

As if the origin of a word we used

without thinking could help us deal

with what we were about to lose

without thinking:

a small room

gloomy with machines, with

a hand crank and a leather treadle

where I saw a woman standing,

years ago, her paired shoes

in her hands and already

I was placing them in some ideal

river village

where someone said

I'll make up a bed for you

and immediately

I could hear the chime

of another childhood: a spare room

perfumed by windfalls in one corner,

porcelain ornaments on a traycloth,

a painting on the wall of a flowered lane

I wanted them to walk down

until they wandered

into the dusk

of another word: this time nostalgia.

The first part of it nostos, meaning

the return home.

- Eavan Boland

The Treepenny Review Fall 2014

Hoài hương

Khi cái tiệm bồ tèo ở trong làng

Đóng cửa, với tờ giấy, vài hàng viết tay, xin lỗi,

ở cửa sổ

Vào một chiều tối có gió

Khi lũ quạ ngồi, với những cái vai kếch xù,

Với cái lưng quay về cú rùng mình sau cùng

của ánh sáng

Tớ bị quần thảo, không phải bởi một bài ai điếu, hay một

bi khúc

Nhưng mà là, một đam mê, săn đuổi cái nghĩa

ban đầu của 1 từ.

Ceapail chắc có nghĩa là binding [trói

buộc], hay fettering [rằng buộc]?

Klabba, từ tiếng Thụy Điển?

Giống như cololere, vá giầy.

Như thế, cái khởi thuỷ, cái gốc của một từ chúng

ta dùng

chẳng suy nghĩ

có thể giúp chúng ta lèm bèm về 1

cái gì

chúng ta mất

[cũng] chẳng suy tư cái con mẹ gì cả!

Một căn phòng nhỏ

Âm u, lù tà mù, với những máy móc

Một cái quay tay, một cái bàn đạp bằng da

Nơi tôi nhìn thấy 1 người đàn bà đứng

Nhiều năm trước đây

Đôi giầy của nàng trên tay nàng

Và tôi bèn coi như đã làm rồi, cái

việc

Để chúng vào trong con sông lý tưởng nào

đó

Con sông làng

Nơi có người nào nói

Ta sẽ làm giường cho mi

Và liền lập tức

Tôi có thể nghe tiếng chuông đổ

Của một thời thơ ấu khác: một căn phòng dư,

Dậy mùi táo từ một góc phòng

Những đồ trang trí bằng sành trên một cái

khay bằng vải

Một bức vẽ trên tường, một con đường đầy hoa

Tôi muốn chúng bước ra khỏi bức họa

Cho tới khi chúng đi dạo vào hoàng hôn

Của một từ khác: hoài hương

Cái phần đầu của từ này, nostos

Có nghĩa là,

Nhớ Saigon.

Love Poem

Feather duster.

Birdcage made of whispers.

Tail of a black cat.

I'm a child running

With open scissors.

My eyes are bandaged.

You are a heart pounding

In a dark forest.

The shriek from the Ferris wheel.

That's it, bruja

With arms akimbo

Stamping your foot.

Night at the fair.

Woodwind band.

Two blind pickpockets in the crowd.

Charles Simic: Jackstraws

Thơ Tình

Chổi lông gà quét

bụi

Lồng chim làm bằng những lời thì

thầm

Đuôi mèo đen

Gấu là đứa trẻ chạy

Với cây kéo mở

Mắt dán băng

Em của Gấu ư?

Trái tim nện thình thịch

Trong khu rừng âm u

Tiếng rít từ bánh xe Ferris

Vậy đó, bruja

Tay chống háng

Dậm chân

Đêm hội

Băng Woodwind

Hai tên móc túi mù

Trong đám đông.

My shadow and your shadow on the wall

Caught with arms raised

In display of exaggerated alarm,

Now that even a whisper, even a breath

Will upset the remaining straws

Still standing on the table

In the circle of yellow lamplight,

These few roof-beams and columns

Of what could be a Mogul Emperor's palace.

The Prince chews his long nails,

The Princess lowers her green eyelids.

They both smoke too much,

Never go to bed before daybreak.

Charles Simic: Jackstraws

Rút cọng rơm

Bóng của GNV và của BHD thì ở trên tường

Xoắn vào nhau, bốn cánh tay dâng cao

Trong cái thế báo động hơi bị thái quá,

Và bây giờ, chỉ cần một lời thì thầm,

Có khi chỉ một hơi thở thật nhẹ

Cũng đủ làm bực mình cả đám còn lại

Vẫn đứng trên mặt bàn .

Trong cái vòng tròn ánh sáng

đèn màu vàng

Vài cây xà, cây cột

Của cái có thể là Cung Ðiện của Hoàng

Ðế Mogul.

GNV cắn móng tay dài thòng,

BHD rủ cặp mí mắt xanh.

Cả hai đều hút thuốc lá nhiều quá,

Chẳng bao giờ chịu đi ngủ trước khi đêm qua.

Beauty Parlor

School of the deaf with a playground

In a tangle of dead weeds and trash

On a street of torched cars and vans,

Here then is the white and red banner,

Grime-streaked and wind-torn,

Still inviting us to the GRAND OPENING.

The one with a flamethrower hairdo

Who set all our hearts on fire,

Where is she today? I inquired

Of a ragged little tree in front,

While its branches took swipes at my head

As if to knock some sense into me.

Charles Simic: Jackstraws

Tiệm Làm Đẹp

Trường của những người điếc với một cái sân chơi

Hầm bà làng những cỏ khô và rác

rến

Trên một con phố với những xe như những ngọn đuốc

Chỗ này, chỗ kia, là những băng vải, trắng và

đỏ

Bụi bặm, rách bươm vì gió

Nhưng vưỡn mời chúng ta vào Ngày Hội Lớn

Cái em kỳ nữ gì gì đó

Với cái băng đô đỏ rực

Làm tim chúng ta cũng rực đỏ theo màu cờ

Em đó bi giờ đâu nhỉ? Gấu bèn hỏi

Cái cây nhỏ, tả tơi, trước mặt,

Cành của nó lòa xòa xoa đầu Gấu

Như muốn gõ bật ra một ý nghĩa nào đó.

SIXTEEN

Loving the World Anyway

I should be content

to look at a mountain

for what it is

and not as a comment

on my life.

-DAVID IGNATOW

Three brief images-one Chippewa, one Turkish, and one West African-move

the focus of a man's attention from self to world.

Ba hình ảnh ngắn ngủi chuyển sự chú tâm của

con người, từ nó tới thế giới.

SOMETIMES I GO ABOUT PITYING MYSELF

Sometimes I go about pitying myself,

and all the time

I am being carried on great winds across the sky.

Chippewa music adapted from the translation by Frances

Densmore

Đôi khi Gấu tự thương hại

Gấu

Đôi khi Gấu tự thương hại Gấu

Và suốt thời gian đó thì

Gấu được những trận gió lớn chở đi tung tăng khắp thế gian!

UNITY

The horse's mind

Blends

So swiftly

Into the hay's mind

FAZIL HUSNU DAGLARCA

translated by Talat Sait Halman

Một mối

Tâm trí, thần hồn chú ngựa

Thì bèn quấn quýt với linh hồn cỏ khô

OLD SONG

Do not seek too much fame,

but do not seek obscurity.

Be proud.

But do not remind the world of your deeds.

Excel when you must,

but do not excel the world.

Many heroes are not yet born,

many have already died.

To be alive to hear this song is a victory.

Traditional, West Africa

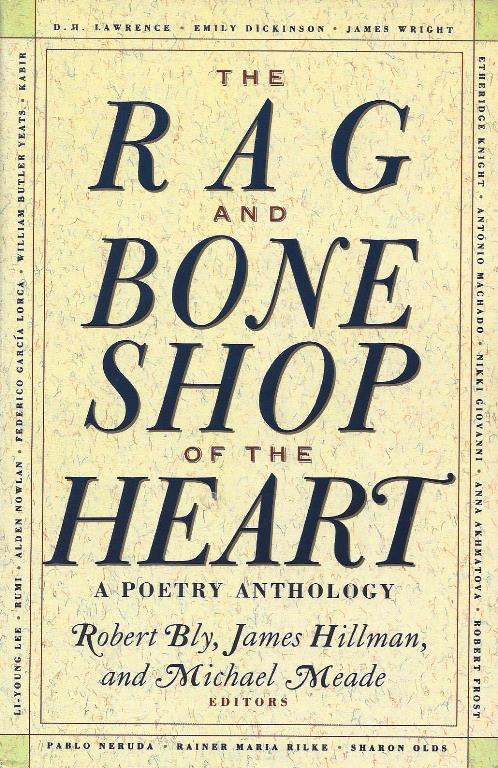

The Rag and the Bone Shop of the Heart

A Poetry Anthology

Robert Bly, James Hillman and Michael Meade editors

Một trang Tin Văn cũ

Đừng tìm kiếm danh vọng nhiều quá

Nhưng đừng tìm kiếm sự tối tăm.

Hãy hãnh diện

Nhưng cũng đừng nhắc nhở thế giới về những chiến công của

bạn

Chơi trội, OK, nếu bạn phải chơi trội.

Nhưng đừng chơi trò nổi cộm với cả thế gian

Nhiều vị anh hùng chưa sinh ra

Nhiều người đã chết

Sống, và vô 1 trang TV cũ, đọc, thì đã

là một chiến thắng khổng lồ rồi!

BREASTS

I love breasts, hard

Full breasts, guarded

By a button.

They come in the night.

The bestiaries of the ancients

Which include the unicorn

Have kept them out.

Pearly, like the east

An hour before sunrise,

Two ovens of the only

Philosopher's stone

Worth bothering about.

They bring on their nipples

Beads of inaudible sighs,

Vowels of delicious clarity

For the little red schoolhouse of our mouths.

Elsewhere, solitude

Makes another gloomy entry

In its ledger, misery

Borrows another cup of rice.

They draw nearer: Animal

Presence. In the barn

The milk shivers in the pail.

I like to come up to them

From underneath, like a kid

Who climbs on a chair

To reach a jar of forbidden jam.

Gently, with my lips,

Loosen the button.

Have them slip into my hands

Like two freshly poured beer-mugs.

I spit on fools who fail to include

Breasts in their metaphysics,

Star-gazers who have not enumerated them

Among the moons of the earth ...

They give each finger

Its true shape, its joy:

Virgin soap, foam

On which our hands are cleansed.

And how the tongue honors

These two sour buns,

For the tongue is a feather

Dipped in egg-yolk.

I insist that a girl

Stripped to the waist

Is the first and last miracle,

That the old janitor on his deathbed

Who demands to see the breasts of his wife

For one last time

Is the greatest poet who ever lived.

O my sweet, my wistful bagpipes.

Look, everyone is asleep on the earth.

Now, in the absolute immobility

Of time, drawing the waist

Of the one I love to mine,

I will tip each breast

Like a dark heavy grape

Into the hive

Of my drowsy mouth.

CHARLES SIMIC

That the old janitor on his deathbed

Who demands to see the breasts of his wife

For one last time

Is the greatest poet who ever lived.

Làm nhớ

NGUYỄN TÔN NHAN

Đời chẳng cho ta chút gì cả

Một mảnh không gian thở ngợp người

Gió tạt hôm kia môi phai má

Nắng ngườm bữa nọ má hoàn môi

Từ chốn không quen mà chẳng lạ

Ta đi về tới dứt luân hồi

Em bồng ngây dại ra hong

tóc

Sớm bay tạt hết khô mồ hôi

Lồng lộng trời cao sa xuống thấp

Không cho ngửi chút ngái trong người

Thì ra ta vẫn thèm ghê gớm

Xin cho ngửi đến chết mùi đời

Hỡi ơi mộng ngắn như gang tấc

Đo chẳng vừa nào nắng cứ phai

Mưa cứ tạt cho bay nửa giấc

Ta chẳng còn biết nhớ mong ai

Một mảnh không gian nho

nhỏ thở

Ngày sau thoi thóp thoáng hương nhài

Hay là hương của em xưa cũ

Vỡ nửa dưới thềm hơi hướng rơi.

1995

Hihi, a2a rule No.#1 :

K

Tks and Best Regards and Take Care

GCC

Jun 17 at 7:15 PM

Tối qua, TB 15.6.18 vợ chồng tớ dự tiệc cưới của con trai Hàm.

Hình này do bà xã tớ chụp

NKL’s

TKS

Chúc Mừng bạn Hàm và gia đình.

NQT’s

Hình: Quyên & Hàm & Lãng

Dear ông Gấu

chúc mừng Jennifer và Richie lên

lớp. ("hôm qua đi học rồi mà!") (1)

gửi ông Gấu một clip xem cho vui

tks

DHQ

Tks

GCC's

(1)

Lần về Saigon, Gấu có ghé quán. Bà chủ

quán, chắc đã mất, con cháu kế nghiệp, chắc thế.

Dương Nghiễm Mậu cũng hay ngồi quán này, nhưng Gấu chưa từng

gặp. Quán hủ tíu, cũng quán nhà, phía

bên kia đường, nổi tiếng chẳng kém cà phê Thái

Chi. Còn 1 tiệm cũng thần sầu của thời ô mai, tiệm ô

mai, ở xa xa 1 chút, về phía chợ Tân Định. Rồi quán

bánh cuốn Thanh Trì, chủ nhật có món bún

thang, cũng khu này, rồi quán cà phê Huy Tưởng,

ui choa, và nao nức cả 1 thời chưa nhớn mà đã già,

đã chết, đã hăm he mang kỷ niệm về phía bên

kia…

http://www.tanvien.net/sangtac/st03_lan_cuoi_sg.html

....

Một Sài-gòn trong có quán cà phê

Thái Chi ở đầu đường Nguyễn Phi Khanh, góc Đa Kao. Bà

chủ quán khó tính, chỉ bằng lòng với một dúm

khách quen ngồi dai dẳng như muốn dính vào tuờng,

với dăm ba tờ báo Paris Match, với mớ bàn ghế lùn tịt.

Trên tường treo một chiếc dĩa tráng men, in hình một

cậu bé mếu máo, tay ôm cặp, với hàng chữ Pháp

ở bên dưới: "Đi học hả? Hôm qua đi rồi mà!"

Đó là nơi em tôi

thường ngồi lỳ, trong khi chờ đợi Tình Yêu và Cái

Chết. Cuối cùng Thần Chết lẹ tay hơn, không để cho nạn

nhân có đủ thì giờ đọc nốt mấy trang Lục Mạch Thần

Kiếm, tiểu thuyết chưởng đăng hàng kỳ trên nhật báo

Sài-gòn, để biết kết cục bi thảm của mối tình Kiều

Phong-A Tỷ, như một an ủi mang theo, thay cho những mối tình tưởng

tượng với một cô Mai, cô Kim nào đó, như một

nhắn nhủ với bạn bè còn sống: "Đừng yêu sớm quá,

nếu nuốn chết trẻ." Chỉ có bà chủ quán là

không quên cậu khách quen. Ngày giỗ đầu của

em tôi, bà cho người gửi tới, vàng hương, những lời

chia buồn, và bộ bình trà "ngày xưa cậu Sĩ

vẫn thường dùng."

Auden

Poet's Choice

39·

YEHUDA AMICHAI

Once you were my guardian,

Now I am your guard.

AFTER MY father died, one of the first poems I wanted to reread was

Yehua Amichai's "Letter of Recommendation." I first read this lyric

in the Israeli poet's book Amen in 1977, and it has remained with

me ever since as a model of sacred passion, of unabashed feeling and precise

tenderness.

LETTER OF RECOMMENDATION

On summer nights I sleep naked

in Jerusalem on my bed,

which stands on the brink

of a deep valley

without rolling down into it.

During the day I walk about,

the Ten Commandments on my lips

like an old song someone is humming to himself

Oh, touch me, touch me, you good woman!

This is not a scar you feel under my shirt.

It's a letter of recommendation, folded,

from my father:

"He is still a good boy and full of love."

I remember my father waking me up

for early prayers. He did it caressing

my forehead, not tearing the blanket away.

Since then I love him even more.

And because of this

let him be woken up

gently and with love

on the Day of Resurrection.

(TRANSLATED BY YEHUDA AMICHAI AND TED HUGHES)

Amichai's poems keep what he calls "the route to

childhood open." They speak with warmth, nostalgia, and reverence for

his dead father. Playful wit doesn't work against the feeling in this

poetry, but in tandem with it. Unlike many contemporary poets here and

abroad, Amichai doesn't fear showing too much emotion in his work, and he

often lets his love songs ("Oh, touch me, touch me, you good woman!") turn

into memorial poems and prayers for the dead.

I love the human scale-the vulnerable presence-in Amichai's poetry,

and I can't help feeling that the example of a sweet, gentle, and religious

Jewish father stands as an implicit challenge to other more traditional

hyper-aggressive societal models of fatherhood and masculinity.

Do we become like parents to the dead? In "My Father's

Memorial Day," Amichai visits not just his father's graveside but all those

buried with him in a single row, a group of people yoked together by death,

"his life's graduation class." I'm struck by the complete confidence he

has in the mutual, ongoing love that persists between his father and him

("My father still loves me, and I / Love him always, so I don't weep") and

the way the poem then opens out into a lyric that tries to do justice to

the genuine human sadness of the cemetery it-self Amichai's feeling extends

to embrace the suffering of others ("I have lit a weeping in my eyes"). He

concludes with a kind of ritual mourning-a parental feeling-for someone

else's child:

MY FATHER'S MEMORIAL DAY

On my father's memorial day

I went out to see his mates-

All those buried with him in one row,

His life's graduation class.

I already remember most of their names,

Like a parent collecting his little son

From school, all of his friends.

My father still loves me, and I

Love him always, so I don't weep.

But in order to do justice to this place

I have lit a weeping in my eyes

With the help of a nearby grave-

A child's. "Our little Yossy, who was

Four when he died."

(TRANSLATED BY YEHUDA AMCHHAI AND TED HUGHES)

130.

FAREWELL

Another year gone-

hat in my hand,

sandals on my feet.

-BASHO

GOOD-BYES ARE POIGNANT. They belong to the part of life that's

to write about. I'd like to close with a special nod to the reader,

I think of as a friend. I'd like to sign it with a wave and even a good-bye,

the lyric as farewell. As Wallace Stevens writes, "That wo be waving and

that would be crying, I Crying and shouting meaning farewell" ("Waving

Adieu, Adieu, Adieu").

My grandfather taught me that, when a friend or relative was

leaving on the train, we should stand on the platform and continue waving

until the train had disappeared. It was something he learned a Japanese

friend. I was delighted to find this notion confirmed Robert Aitken's

illuminating book A Zen Wave, in which he remarks

that the Japanese say good-bye to the very end: "They wave and waving

until their friends are out of sight." He points this out as part of a

commentary on one of Basho's poems, which Robert Hass renders:

Seeing people off,

being seen off-

autumn in Kiso.

Basho seems to be saying that for him, fall in Kiso is the time

of departures. It is almost the outcome-the upshot-of our leave-taking.

Now we say good-bye to our friends; now our friends say good-bye to

us.

The experience of seeing off a friend is also

important in Chinese poetry. Here is Ezra Pound's version of a striking

poem that wanderer Li Po wrote in 754 about parting from a dear one

in Hsuancheng. Pound's lyrical adaptation first appeared as one of "Four

Poems of Departure" in Cathay (1915). (There

is also a strong version of this poem in Red Pine's Poems of the Masters.)

TAKING LEAVE OF A FRIEND

Blue mountains to the north of the walls,

White river winding about them;

Here we must make separation

And go out through a thousand miles of dead grass.

Mind like a floating wide cloud,

Sunset like the parting of old acquaintances

Who bow over their clasped hands at a distance.

Our horses neigh to each other

as we are departing.

"Dear friend whoever you are take this kiss, /I give it especially

to you, do not forget me," Whitman declared in one of his songs of parting,

"So Long!" (He also boldly announced, "Camerado, this is no book, / Who

touches this touches a man.") I'd like to close with lines of farewell

from the twenty-fourth section of the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass.

Whitman was unabashed about addressing and embracing each stranger, each

one of us, as a dear familiar, about imagining the exchange between poet

and his unknown reader as a form of creative love. I leave these lines

to each individual reader, to each one of you, as a fleeting final gesture

of our shared participation in poetry:

Lift me close to your face till I whisper,

What you are holding is in reality no book, nor part of a book,

It is a man, flushed and full-bodied-it is I- So long!

We must separate-Here! take from my lips this kiss,

Whoever you are, I give it especially to you;

So long-and I hope we shall meet again.

Note: Bài viết đóng lại Poet's Choice. Bài

haiku của Basho, làm Gấu nhớ tới bài của Nguyễn Bính,

"cánh buồm nâu, cánh buồn nâu, cánh

buồm... "

Nhìn người đi

đi-

mùa thu ở Kiso.

Bài thơ của Đỗ Phủ, cũng... OK. Nó làm

Gấu, không phải nhớ tới Nguyễn Bính, mà, chính

Gấu, lần tính farewell, ở PLT, tếu thế!

To Please a Shasow

J. Brodsky

…

Yeats’s [Bài thơ tưởng niệm Yeats của Auden. NQT] last, with

its shuddering

The mercury sank in the mouth of the dying day.

They overshadowed that unforgettable rendition of stricken body as

a city whose suburbs and squares are gradually emptying as if after a

crushed rebellion. They over-shadowed even that statement of the era

. . . poetry makes nothing happen....

They, those eight lines in tetrameter that made this third part of

the poem sound like a cross between a Salvation Army hymn, a funeral

dirge, and a nursery rhyme, like this:

Time that is intolerant

Of the brave and innocent,

And indifferent in a week

To a beautiful physique,

Worships language and forgives

Everyone by whom it lives;

Pardons cowardice, conceit,

Lays its honors at their feet

Thời gian vốn không khoan

dung

Đối với những con người can đảm và thơ ngây,

Và dửng dưng trong vòng một tuần lễ

Trước cõi trần xinh đẹp,

Thờ phụng ngôn ngữ và

tha thứ

Cho những ai kia, nhờ họ, mà nó sống;

Tha thứ sự hèn nhát và trí trá,

Để vinh quang của nó dưới chân chúng.

I remember sitting there in the small wooden shack, peering through

the square porthole-size window at the wet muddy, dirt road with a few

stray chickens on it, half believing what I'd just read, half wondering whether

my grasp of English wasn't playing tricks on me. I had there a veritable

boulder of an English-Russian dictionary, and I went through its pages time

and again, checking every word, every allusion, hoping that they might spare

me the learning that stared at me from the page. I guess I was simply refusing

to believe that way back in 1939 an English poet had said, "Time ... worships

language," and yet the world around was still what it was.

But for once the dictionary didn't overrule me.

Auden had indeed said that time (not the time) worships language,

and the train of thought that statement set in rnotion in me is still

trundling to this day. For "worship" is an attitude of the lesser toward

the greater. If time worships language, It means that language is greater,

or older, than time, which is, in its turn, older and greater than space.

That was how I was taught, and I indeed felt that way. So if time – which

is synonymous with, nay, even absorbs deity-worships language, where then

does language come from? For the gift is always smaller than the giver.

And then isn't language a repository of time? And isn't this why time worships

it? And isn't a song, or a poem, or indeed a speech itself, with its caesuras,

pauses, spondees, and so forth, a game language plays to restructure time?

And aren't those by whom language "lives" those by whom time does too? And

if time "forgives" them, does it do so out of generosity or out of necessity?

And isn't generosity a necessity anyhow?

….

Brodsky: To Please a Shadow

Note: Cuốn thơ tiếng Anh, hóa ra của 1 người bạn ở Moscow,

Gấu nhớ lộn, của 1 độc giả, tội nghiệp nhà thơ bị nhà nước

lưu đầy nội xứ, gửi tặng. Nhưng cái cảnh Brodsky đọc nó- remember

sitting there in the small wooden shack, peering through the square porthole-size

window at the wet muddy, dirt road with a few stray chickens on it…, thì

đúng như Gấu còn nhớ, và nó làm Gấu

nhớ đến Gấu, lần đầu nghe “Ngày mai đi lượm xác chồng”, ở

nông trường cải tạo Đỗ Hoà, Nhà Bè.

Cái sự ngộ ra cả 1 cõi thơ, trong có cõi

thơ của mình, mà Brodsky trải qua, khi đọc hai khúc

trên của Auden, quái làm sao, Gấu cũng trải qua -

vào lúc chót đời, khi được Ông Trời trao tặng

món quà thơ, thưởng công làm trang Tin Văn -

khi đọc Milosz, khi ông đọc Simone Weil, Khoảng Cách Là

Linh Hồn Của Cái Đẹp: Nếu không đi tù VC, là

Gấu không làm sao hiểu được, cái hồn của văn chương

Ngụy, là ở trong 1 số bài nhạc sến của chúng.

Sao không hát cho những người vừa nằm xuống chiều qua?

V/v Vưỡn chuyện Cái Ác Bắc Kít:

Marlene Dietrich by David Levine

GABRIELE ANNAN

Girl From Berlin

Originally published February 14,1985, as a review

of Marlene Dietrich's ABC, Ungar Marlene D. by Marlene Dietrich. Grasset

(Paris) Sublime Marlene by Thierry de Navacelle. St. Martin's

Marlene Dietrich: Portraits 1926-1960, introduction

by Klaus-Jurgen Sembach, and epilogue by losefvon Sternberg. Schirmer/Mosel;

Grove Marlene a film directed by Maximilian Schell, produced by Karel

Dirka. Dietrich by Alexander Walker. Harper and Row

Among the rarities Schell has to show is a scene from

Orson Welles's Touch of Evil (1958), in which Dietrich was only a guest

star. She plays the madame of a Texas brothel, Welles a corrupt, alcoholic

police chief on the skids. He comes into the brothel and finds her alone

at a table in the hall.

"You've been reading the cards, haven't you?" [he says].

"I've been doing the accounts."

"Come on, read the future for me."

"You haven't got any."

"Hm ... what do you mean?"

"Your future's all used up. Why don't you go home?"

Dietrich's voice is deadpan, but it breaks your heart all right with

a Baudelairean sense of the pathos of human depravity, degradation, and

doom.

“Cô gái từ Berlin” là 1 bài

viết về nữ tài tử điện ảnh người Đức, Marlene Dietrich.

Trong phim “Cánh Đồng Bất Tận", em đóng

vai 1 bướm Xề Gòn, buồn buồn ngồi bói Kiều. Một tên

cớm Bắc Kít bước vô, ra lệnh:

-Coi cho ta 1 quẻ về tương lai.

Ngài đâu còn?

-Mi nói sao?

Tương lai của Ngài xài hết rồi, sao Ngài không

về lại xứ Bắc Kít của Ngài đi?

Giọng em bướm trong Cánh Đồng Bất Tận mới dửng dưng, bất cần

đời làm sao, nhưng bất cứ 1 tên Mít nào nghe

thì cũng đau thốn dế, khi nghĩ đến 1 xứ Mít tàn tạ

sau khi Bắc Kít chiếm trọn cả nước.

Đúng là THNM!

Số báo này, câu đề từ của nó,

đúng câu mà Gấu đã từng chôm, để vinh

danh thơ trẻ ở trong nước:

Thousands have lived without love, not one without

water

W.H. Auden, 1957

http://www.tanvien.net/g…/gt_tho_toi_khong_danh_cho_ban.html

Xin trao thi sĩ vòng hoa tặng : Auden, nhà

thơ người Anh, khi được hỏi, hãy chọn bông hoa đẹp nhất trong

vòng hoa tặng, ông cho biết, bông hoa đó đã

tới với ông một cách thật là khác thường. Bạn

của ông, Dorothy Day, bị bắt giam vì tham gia biểu tình.

Ở trong tù, mỗi tuần, chỉ một lần vào thứ bẩy, là

nữ tù nhân được phép lũ lượt xếp hàng đi tắm.

Và một lần, trong đám họ, một tiếng thơ cất lên, thơ

của ông, bằng một giọng dõng dạc như một tuyên ngôn:

"Hàng trăm người sống không cần tình

yêu,

Nhưng chẳng có kẻ nào sống mà không cần nước"

Khi nghe kể lại, ông hiểu rằng, đã không

vô ích, khi làm thơ.

Và. đúng như Gấu tiên đoán,

Brodsky được vinh danh, qua số báo, nhờ tác phẩm Thuỷ Ấn,

viết về Venice, post sau đây

Tuy nhiên, cả số báo, là nhằm vinh danh xứ Nam Kít,

và thứ văn chương của nó, như sông lạch:

Too often, where we need water we find guns

Ban Ki–moon 2008

Câu trên, 1 cách nào đó,

giải thích 30 năm nội chiến từng ngày.

1992: Venice

WAVE THEORY

I always adhered to the idea that God is time, or at least that his spirit

is. Perhaps this idea was even of my own manufacture, but now I don't remember.

In any case, I always thought that if the spirit of God moved upon the

face of the water, the water was bound to reflect it. Hence my sentiment

for water, for its folds, wrinkles, and ripples, and-as I am a Northerner-for

its grayness. I simply think that water is the image of time, and every