TƯỞNG NIỆM I II Tribute to Solz 1 [Tribute] 2 [Tribute_solz] 3 [Tribute1] 4 [Tribute 2] 5 [Tribute 3] 6 [Tribute 4] 7 [Tribute 5] 8 [Solz1] 9 [Solz 2] 10 [Solz 3] |

....

Alexander Solzhenitsyn, tác

giả các cuốn ‘Bán đảo Gulag' (the Gulag Archipelago) và ‘Một ngày

trong cuộc

đời Ivan Denisovich’ (One Day In The Life Of Ivan Denisovich), đã trở

về Nga

năm 1994... Thú

thực Gấu không thể tưởng

tượng mấy anh Yankee mũi tẹt làm cho Bi Bi Xèo ngu dốt đến mức như thế

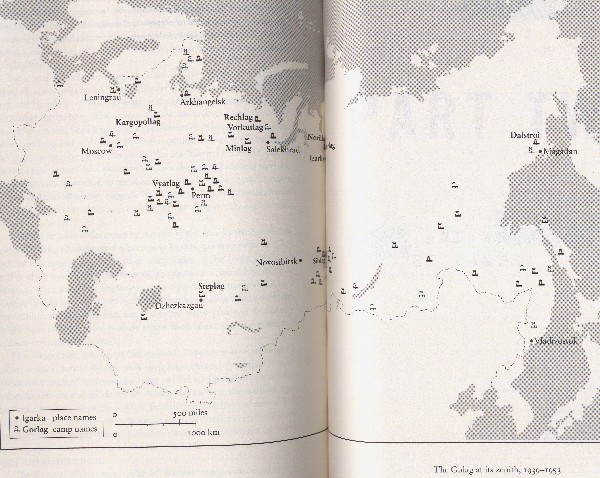

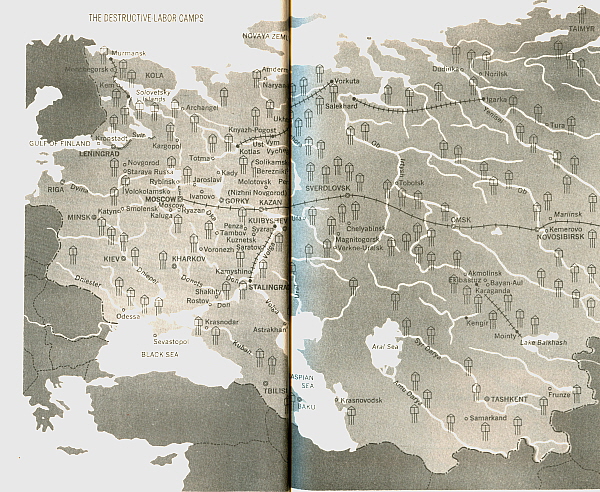

này!   (1) Lấy từ Gulag a history, của Anne Applebaum (2). Từ Quần đảo Gulag, của Solz, bản rút gọn Gulag, a history Cái gọi là văn

chương Miền

Nam, trước 1975, ngày càng lộ ra như một toàn thể, không một nhà văn

nào có thể

bị chia cắt ra khỏi một nhà văn nào, trừ những anh VC nằm cùng, tất

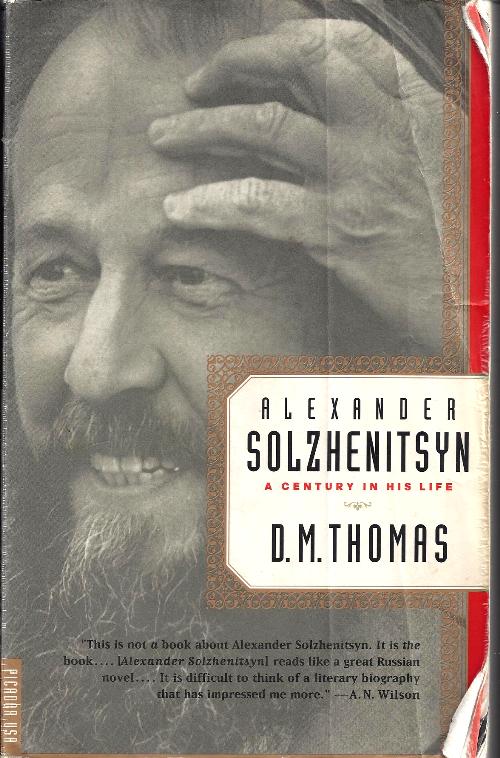

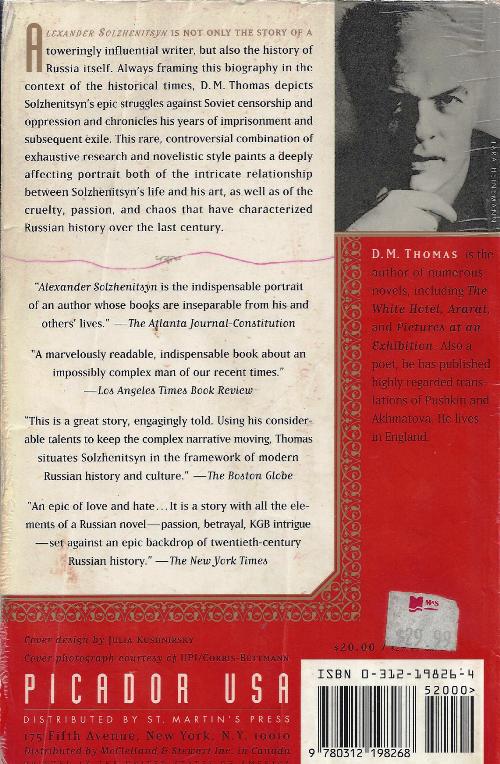

nhiên.   Alexander Solzhenitsyn: Thế kỷ

ở trong ta. Trong bài tựa, D.M. Thomas viết,

Solz đã giúp trong cái chuyện hạ gục nền độc tài vĩ đại nhất thế giới,

kể từ trước

tới nay, ngoài ra còn dậy cho Tây phương biết, Cái Ác đầy đủ của nó

khủng

khiếp ghê rợn là dường nào, its full horror. Không nhà văn nào của thế

kỷ 20 có

một tầm ảnh hưởng như ông trong lịch sử. Một thứ cầu nguyện, theo Thomas. Không phải theo kiểu thường nhân ghé đứng chụp hình kế bên Shakespeare, vừa tưởng niệm vừa hưởng tí vinh dự: Solz nhìn ở Pushkin như người đồng thời của mình. Nhưng cái cử chỉ, hành động ghé tượng Pushkin đã khiến Thomas có một vision về cuốn sách mình sẽ viết. Nó làm ông nhớ đến bài thơ hách xì xằng của Pushkin, Kỵ Sĩ Đồng, 1833. Ui chao, lạ làm sao, nó làm Gấu nhớ tượng Đức Thánh Trần và ngón tay của Người chỉ ra cửa biển Vũng Tầu! Một linh hồn lưu vong Không hiểu ngày nay, ở quê hương Việt Nam thân yêu của chúng ta, còn có những đồng bào hong hóng chờ tới giờ phát thanh bằng tiếng Việt của một VOA, một BBC?… Những người dân Nga đã có thời trải qua những giờ phút như vậy, và Solzhenitsyn hiểu rằng, những đồng bào của ông, đâu phải ai cũng có cơ may, hoặc có đủ can đảm, cầm trong tay một ấn bản in lén lút tác phẩm của ông. Họ biết về Hy Vọng Dù Không Còn Hy Vọng, biết những sự thực nóng bỏng ở trong những tác phẩm của ông, những cuốn tiểu thuyết, và nhất là tác phẩm mang tính tài liệu lớn lao của ông, Quần Đảo Gulag: họ biết chúng, qua những tiếng còn tiếng mất, của những làn sóng ngắn các đài phát thanh Tây Phương. The Old Days PROLOGUE I ASKED A

RETIRED KGB COLONEL, NOW GIVEN THE JOB OF IM-proving Russia's image

abroad,

what image he would choose to represent the beginning of the Bolshevik

era. We

were at a Helsinki hotel, overlooking the frozen sea. Some mutual

friends had

said he knew something about KGB attempts on Solzhenitsyn's life; he

was

disappointingly vague on that subject, but enjoyed talking with me

about

Russian history and art over a bottle of vodka. "What

image?" he mused, gazing out through the icy window at the Gulf of

Finland. A few weeks before, a car ferry, the Estonia, had sunk in

heavy seas,

with a thousand deaths. It had seemed, we had agreed, an apt image for

the end

of Communism: a tiny crack, widening swiftly through a weight of water,

capsizing the unbalanced boat. "I would choose," he replied at last,

"a moment described in Nathan Milstein's autobiography. As a symbolic

beginning,

you understand. Milstein was a music student in Petersburg during the

First

World War. And he writes that, in 1916, in the winter, he was walking

along the

Moika Canal. In front of the Yousoupov Palace he heard agitated voices,

and saw

people craning to look over the parapet into the frozen river. So

Milstein

looked down too, and saw some of the ice was broken, and there, the

water had

pink swirls in it. People around him were shouting, 'Rasputin! Bastard!

Serve

him right!' Milstein realized the pinkish swirls were the blood of

Rasputin-one

of the most powerful men in the empire. Imagine it: hurrying along a

frozen

canal-a day in December like this one, perhaps late for a violin

lesson-and you

see Rasputin's blood! ... Well, I've seen lots of blood, even shed

quite a lot

of it. ... But anyway, if I were a writer, or maybe a filmmaker, that's

how I'd

start: looking down at broken ice and seeing swirls of blood. Like a

dream ...

" Beginning

this biography, I see the old KGB man and the swirl of Rasputin's

blood. The

single most important aspect of Solzhenitsyn's life is that he was born

a year

after the Bolshevik Revolution. He is "October's twin." Other great

Russian writers who suffered intensely under Communism, but who spent

their

childhood and youth in normal bourgeois circumstances under tsarism,

can refer

to the beginning of their lives with a lucid definiteness. Anna

Akhmatova:

"I was born in the same year [1889] as Charlie A Chaplin, Tolstoy's Kreuzer Sonata, the Eiffel Tower, and,

it seems, T. S. Eliot."

(1). Boris Pasternak: "I was born in 1890 in Moscow, on the 29th of

January

according to the Old Calendar, in Lyzhin's house opposite the Seminary

in

Oruzheiny Street. Surprisingly, something has remained in my memory of

my walks

in autumn with my wet-nurse in the Seminary park-sodden paths heaped

with

fallen leaves, ponds and artificial hills, the painted Seminary

railings, the

noisy games and fights of the seminarists during their recreation. " (2) The

lighthearted juxtaposition of Chaplin and Eliot in the former, and the

rich

sensuous detail in the latter, have no counterpart in Solzhenitsyn's

brief

references to his childhood. No other writer has used his adult life as

material

to the degree Solzhenitsyn has done, yet from the very beginnings one

finds a

kind of Dickensian fog and murk. Perhaps one consequence of this was

that,

while he seemed to develop a very sure sense of identity, he

continually

explored different fictional self-portrayals-Nerzhin in The

First Circle, Kostoglotov in Cancer Ward,

Vorotyntsev in August

1914-as if the misty beginnings make him need to keep looking for

himself. His

self-representations are of the fully grown man-soldier, writer, zek;* not, however, husband or lover,

with rare exceptions; and for any "portrait of the artist as a young

man" or as a child we look in vain. Instead of any clear statement of

where and when he was born, there is a sense of confused, almost

mythic, birth.

It could not have been other, for a child born in the turbulence of

1918, and

already fatherless. It was,

after all, the time of facelessness. In Akhmatova's horrifying image of

the

Revolution: As though,

in night's terrible mirror The human

face disappeared, and also its divine image. In the classical world a

slave was

called aprosopos,

"faceless"; literally, one who cannot be seen. The

Bolsheviks gloried in facelessness. Out of that

violent beginning, he became the last in a great line of poets and

novelists

that began with Pushkin. They were more than writers; they were, since

they all

lived under authoritarian or tyrannical regimes, "another government,"

in Solzhenitsyn's phrase: cherished by their fellow Russians because

they felt

a special responsibility to be truthful. Solzhenitsyn's

long life is unique and extraordinary. He has embraced almost the

totality of

his country's terrible century. Born amid chaos; caught up, as a

schoolboy, in

the heavily propagandized excitement of the first Bolshevik years; then

a

front-line Red Army soldier; the shock of arrest, for writing imprudent

letters

criticizing Stalin; the horror of a Lubyanka interrogation, followed by

the

camps and "perpetual exile"; release from it in the milder years of

Khrushchev; sudden fame as the author of One

Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich,

which devastatingly brought what had only been whispered about into the

open;

then, losing favor, becoming a dissident of incredible fearlessness,

and

enterprise; publication of The Gulag

Archipelago, his exposure of the whole Soviet tyranny from Lenin

on;

rearrest and enforced exile from his country-the first Russian to

suffer this

fate since Trotsky; quarrels with his hosts in the West; eventual

return to a

Russia where, for very different reasons, he found it necessary to be a

kind of

dissident still. ... Solzhenitsyn

helped to bring down the greatest tyranny the world has seen, besides

educating

the West as to its full horror. No other writer of the twentieth

century has

had sue an influence on history. But his

story is not of one century alone. When Alexander Tvardovsky, editor of

the

journal Novy Mir, sent for the

unknown writer to discuss the manuscript of Ivan

Denisovich, Solzhenitsyn paused beneath Pushkin's statue in

Strastnaya

Square, "partly to beg for his support, and partly to promise that I

knew

the path I must follow and would not stray from it. It was a sort of

prayer."

(4). This is much more than the respectful homage an English or

American

novelist might pay to a bust of Shakespeare: Solzhenitsyn saw Pushkin

as his

contemporary. When I was

thinking hard and long about whether to accept an invitation to write

this

biography, I had a dream in which I was in the small Cornish town of my

childhood. Suddenly floodwaters rose, and I found myself swept along by

them.

At first it was quite exhilarating-even though I can't swim; I expected

to

round a corner and see my old school; I could cling on to a wall. But

when the

billows swept me round the corner, I saw, in place of the expected road

and

school, a flat sea of turbulent water. Fear gripped me. Along with

many other personal associations, the dream was obviously warning me I

might

drown .if I entered this unfamiliar territory: I am a novelist and

poet, not a

biographer. I might drown under the horrifying weight of a densely

packed life

like Solzhenitsyn's, or under his wrath, since he hates unapproved

biographers

as much as he hated the Soviet censors. Bill I chose

to see the dream in a more positive light. I could see the flood as

pointing in

the direction of one of the great seminal works of Russian literature, Pushkin's The

Bronze Horseman (1833). In that great narrative poem, a flood

sweeps over

St. Pertersbug and devastates the life of "my poor, poor Yevgeni”, a

humble

clerk. Driven mad, Yevgeni shakes his fist at the famous equestrian

statue of

Peter the Great, crying, “All rigid, you wonder-worker, just you wait!”

Peter

was the egoistical monster who had ordered the creation of a capital

city on

marshy Finnish ground. He thought nothing of the thousands of lives his

dream

would cost in the construction of it. But the

Russians still have an admiration for Peter-just as too many of them

still

admire Stalin and would like to see him back. Any reference in a

literary work

of the Bolshevik era to The Bronze Horseman can immediately be

interpreted as a

comment on Stalinism. Russian life and literature is a country, with

limitless

intercommunications-not a history. "Russian literature," wrote the

scholar and translator Max: Hayward, is "a single enterprise in which

no

one writer can be separated from another. Each one of them is best

viewed

through the many-sided prism constituted by all of them taken together.

A later

generation consciously takes up the motifs of its predecessors,

responds to

them, echoes them, and sometimes consummates them in the light of the

intervening historical experience.?" This seems

to me the only worthwhile kind of "writers' union"; and to write a

life of Solzhenitsyn is inevitably to write about a century-or perhaps two. I have

felt myself to be a visitor in the "country of Russian literature"

since

I first inadequately learned Russian during two years of military

service in the

1950s. Being reminded by the dream of that great fellowship of Russian

writers,

for whom two centuries are but a single moment, helped to persuade me

to yield

to the flood, for good or ill. Another persuasion was that

Solzhenitsyn's life

has been a fantastic and inspiring story; but one so complicated by

politics

that it is difficult to see the wood for the plethora of trees. It

challenged

me to use my fictive experience to tell a story that is truly stranger

than

fiction. D.M. Thomas

|