|

|

A Crossbreed

I have a

curious animal, half-cat, half-lamb. It is a legacy from my father. But

it only

developed in my time; formerly it was far more lamb than cat. Now it is

both in

about equal parts. From the cat it takes its head and claws, from the

lamb its

size and shape; from both its eyes, which are wild and changing, its

hair,

which is soft, lying close to its body, its movements, which partake

both of

skipping and slinking. Lying on the window-sill in the sun it curls

itself up

in a ball and purrs; out in the meadow it rushes about as if mad and is

scarcely to be caught. It flies from cats and makes to attack lambs. On

moonlight nights its favorite promenade is the tiles. It cannot mew and

it loathes

rats. Beside the hen-coop it can lie for hours in ambush, but it has

never yet

seized an opportunity for murder.

I feed it on milk; that seems to suit it

best. In long draughts it sucks the milk into it through its teeth of a

beast

of prey. Naturally it is a great source of entertainment for children.

Sunday

morning is the visiting hour. I sit with the little beast on my knees,

and the

children of the whole neighborhood stand round me. Then the strangest

questions

are asked, which no human being could answer: Why there is only one

such

animal, why I rather than anybody else should own it, whether there was

ever an

animal like it before and what would happen if it died, whether it

feels

lonely, why it has no children, what it is called, etc.

I never trouble to answer, but confine

myself without further explanation to exhibiting my possession.

Sometimes the

children bring cats with them; once they actually brought two lambs.

But

against all their hopes there was no scene of recognition. The animals

gazed

calmly at each other with their animal eyes, and obviously accepted

their

reciprocal existence as a divine fact.

Sitting on my knees the beast knows neither

fear nor lust of pursuit. Pressed against me it is happiest. It remains

faithful to the family that brought it up. In that there is certainly

no

extraordinary mark of fidelity, but merely the true instinct of an

animal

which, though it has countless step-relations in the world, has perhaps

not a

single blood relation, and to which consequently the protection it has

found

with us is sacred.

Sometimes I cannot help laughing when it

sniffs round me and winds itself between my legs and simply will not be

parted

from me. Not content with being lamb and cat, it almost insists on

being a dog

as well. Once when, as may happen to anyone, I could see no way out of

my

business difficulties and all that depends on such things, and had

resolved to

let everything go, and in this mood was lying in my rocking-chair in my

room,

the beast on my knees, I happened to glance down and saw tears dropping

from

its huge whiskers. Were they mine, or were they the animal's? Had this

cat,

along with the soul of a lamb, the ambitions of a human being? I did

not

inherit much from my father, but this legacy is worth looking at.

It has the restlessness of both beasts,

that of the cat and that of the lamb, diverse as they are. For that

reason its

skin feels too narrow for it. Sometimes it jumps up on the armchair

beside me,

plants its front legs on my shoulder, and puts its muzzle to my ear. It

is as

if it were saying something to me, and as a matter of fact it turns its

head

afterwards and gazes in my face to see the impression its communication

has

made. And to oblige it I behave as if I had understood and nod. Then it

jumps

to the floor and dances about with joy.

Perhaps the knife of the butcher would be a

release for this animal; but as it is a legacy I must deny it that. So

it must

wait until the breath voluntarily leaves its body, even though it

sometimes

gazes at me with a look of human understanding, challenging me to do

the thing

of which both of us are thinking.

FRANZ KAFKA: Description

of a Struggle (Translated from the

German by Tania and James Stern)

Jorge Luis

Borges: The Book of Imaginary Beings

I have a

curious animal, half-cat, half-lamb. It is a legacy from my father: Tôi

có 1

con vật kỳ kỳ, nửa mèo, nửa cừu. Nó là gia tài để lại của ông già của

tôi

Không phải

ngẫu nhiên mà Gregor Samsa thức giấc như là một con bọ ở trong nhà bố

mẹ, mà

không ở một nơi nào khác, và cái con vật khác thường nửa mèo nửa cừu

đó, là thừa

hưởng từ người cha.

Walter

Benjamin

Một chuyến

đi

Perhaps the

knife of the butcher would be a release for this animal; but as it is a

legacy

I must deny it that. So it must wait until the breath voluntarily

leaves its

body, even though it sometimes gazes at me with a look of human

understanding,

challenging me to do the thing of which both of us are thinking.

Có lẽ con dao của tên đồ tể là 1 giải thoát cho con vật, nhưng tớ đếch

chịu như

thế, đối với gia tài của bố tớ để lại cho tớ. Vậy là phải đợi cho đến

khi hơi thở

cuối cùng hắt ra từ con vật khốn khổ khốn nạn, mặc dù đôi lúc, con vật

nhìn tớ

với cái nhìn thông cảm của 1 con người, ra ý thách tớ, mi làm cái

việc đó đi,

cái việc mà cả hai đều đang nghĩ tới đó!

“Kafka: Những

năm đốn ngộ” là tập nhì, của cuốn tiểu sử hách xì xằng, masterful, về

Kafka của

Reiner Stach. Tập đầu là về những năm từ

1910 tới 1915, khi Kafka còn trẻ, viết như khùng, như điên, writing

furiously,

vào ban đêm, into the night, trong khi cày 50 giờ/tuần. Tập nhì ghi lại

thời kỳ danh vọng trồi

lên, cho tới khi ông mất, ở một viện an dưỡng ở Áo vào tuổi bốn mươi,

sau những

năm tháng đau khổ vì bịnh lao phổi. (Tập thứ ba, ghi lại những năm đầu

đời, đang

tiến hành).

Trong

những

năm sau cùng, từ 1916 tới 1924, Kafka nhận được thư, từ giám

đốc, quản lý nhà băng, chọc quê ông, khi yêu cầu giải thích những

truyện ngắn

do ông viết ra (“Thưa Ngài, Ngài làm tôi đếch làm sao vui được. Tôi mua

cuốn “Hóa

Thân” của Ngài làm quà tặng cho 1 người bà con, nhưng người đó đếch

biết làm

sao xoay sở, hay là làm gì, với cuốn truyện”).

Ai

là nhà

văn của thế kỷ vừa qua?

Đa số đều

cho rằng, ba nhà văn đại diện cho thế kỷ 20 là James Joyce, Marcel

Proust, và Franz Kafka.

Trong ba nhà văn này, người viết xin được chọn Kafka là

nhà văn của thế kỷ 20.

Thế kỷ 20 như chúng ta biết, là thế kỷ của hung bạo. Những

biểu tượng của nó, là Hitler với Lò Thiêu Người, và Stalin với trại tập

trung cải

tạo. Điều lạ lùng ở đây là: Kafka mất năm 1924, Hitler nắm quyền vào

năm 1933;

với Stalin, ngôi sao của ông Thần Đỏ này chỉ sáng rực lên sau

Cuộc Chiến

Lớn II (1945), và thời kỳ Chiến Tranh Lạnh. Bằng cách nào Kafka nhìn

thấy trước

hai bóng đen khủng khiếp, là chủ nghĩa Nazi, và chủ nghĩa toàn trị?

Gần hai chục

năm sau khi ông mất, nhà thơ người Anh Auden có thể viết, không cố

tình nói ngược ngạo, hay tạo sốc: "Nếu phải nêu một tác giả của thời

đại

chúng ta, sánh được với Dante, Shakespeare, Goethe, và thời đại của họ,

Kafka sẽ

là người đầu tiên mà người ta nghĩ tới."

G. Steiner cho rằng:

"(ngoài Kafka ra) không có thể có tiếng nói chứng nhân nào thật hơn, về

bóng đen của thời đại chúng ta." Khi Kafka mất, chỉ có vài truyện ngắn,

mẩu

văn được xuất bản. Những tác phẩm quan trọng của ông đều được xuất bản

sau khi

ông mất, do người bạn thân đã không theo di chúc yêu cầu huỷ bỏ. Tại

sao thế giới-ác

mộng riêng tư của một nhà văn lại trở thành biểu tượng của cả một thế

kỷ?

Nhà phê bình

Mác-xít G. Lukacs cho rằng, trong

những phát kiến (inventions) của Kafka, có những dấu vết đặc thù,

của phê

bình xã hội. Viễn ảnh của ông về một hy vọng triệt để, thật u tối: đằng

sau bước

quân hành của cuộc cách mạng vô sản, ông nhìn thấy lợi lộc của nó là

thuộc về bạo

chúa, hay kẻ mị dân. Cuốn tiểu thuyết "Vụ Án" là một huyền thoại quỉ

ma, về tệ nạn hành chánh mà "Căn Nhà U Tối" của Dickens đã tiên đoán.

Kafka là người thừa kế nhà văn người Anh Dickens, không chỉ tài bóp méo

các biểu

tượng định chế (bộ máy kỹ nghệ như là sức mạnh của cái ác, mang tính

huỷ diệt),

ông còn thừa hưởng luôn cơn giận dữ của Dickens, trước cảnh tượng người

bóc lột

người.

Chọn Kafka

là tiếng nói chứng nhân đích thực, nhà văn của thế kỷ hung bạo, là

chỉ có "một nửa vấn đề". Kafka, theo tôi, còn là người mở ra thiên

niên kỷ mới, qua ẩn dụ "người đàn bà ngoại tình".

Thế nào là

"người đàn bà ngoại tình"? Người viết xin đưa ra một vài

thí dụ: một người ở nước ngoài, nói tiếng nước ngoài, nhưng không thể

nào quên

được tiếng mẹ đẻ. Một người di dân phải viết văn bằng tiếng Anh, nhưng

đề tài

hoàn toàn là "quốc tịch gốc, quê hương gốc" của mình. Một người đàn

bà lấy chồng ngoại quốc, nhưng vẫn không thể quên tiếng Việt, quê hương

Việt. Một

người Ả Rập muốn "giao lưu văn hóa" với người Do Thái...

Văn chương

Việt hải ngoại, hiện cũng đang ở trong cái nhìn "tiên tri"

của Kafka: đâu là quê nhà, đâu là lưu đầy? Đi /Về: cùng một nghĩa như

nhau?

Jennifer Tran

Time:

100 người ảnh hưởng nhất chưa từng sống

Kafka:

Years of insight

Những năm

đốn

ngộ

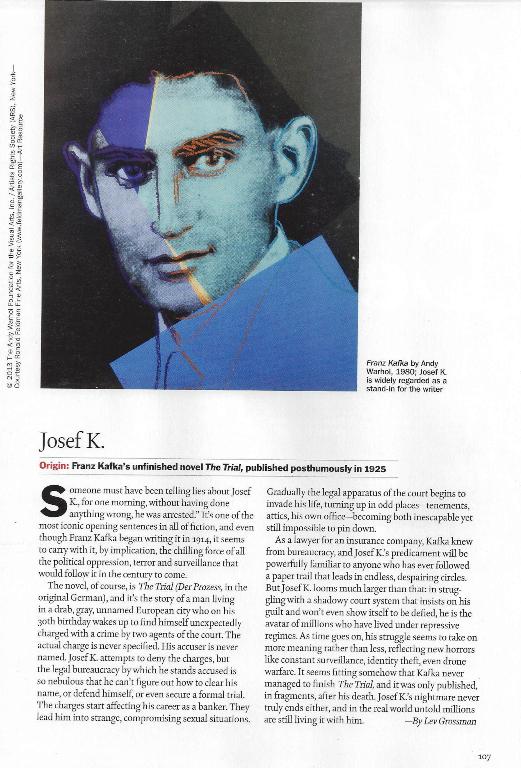

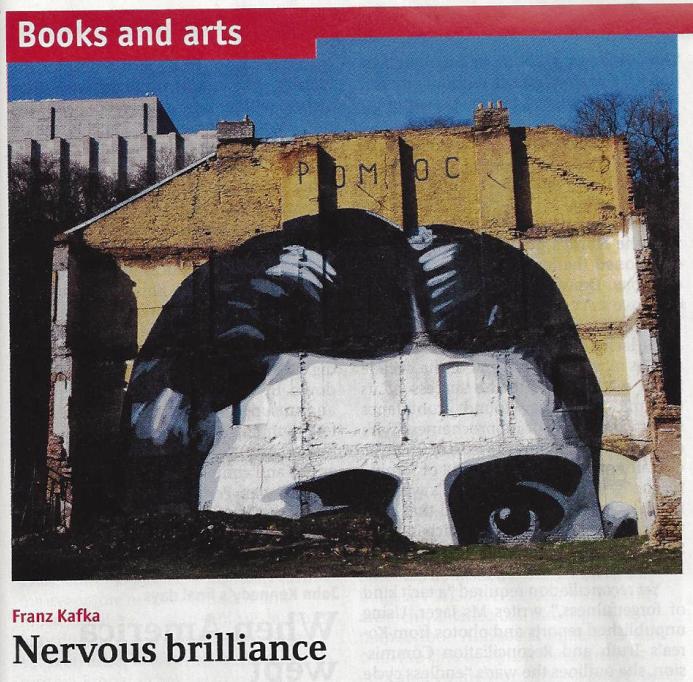

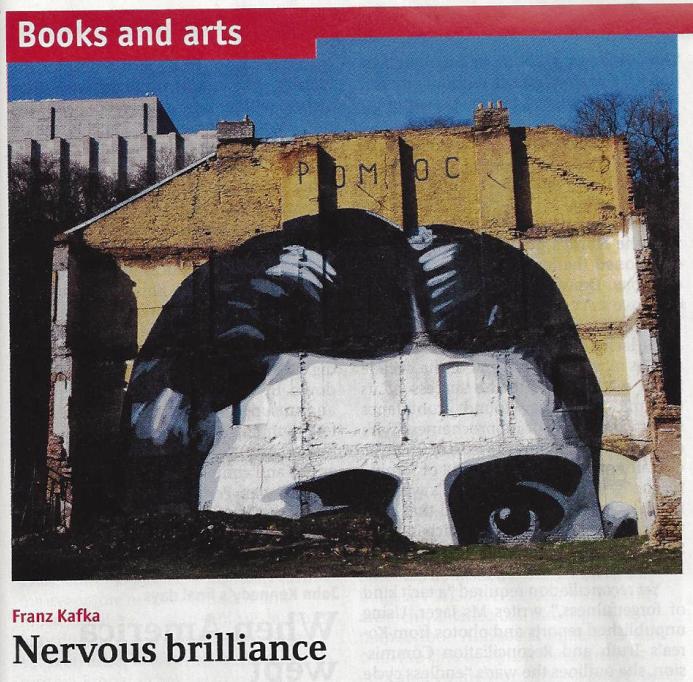

Hình trên

báo giấy còn thấy được 1 con mắt của Kafka.

Note: Nervous brilliance,

tạm dịch, “sáng chói bồn chồn”.

Bỗng nhớ Cô Tư, “sáng chói, đen, và hơi khùng” [thực ra là, “đen, buồn

và hơi

khùng”]

Nhưng cuốn

tiểu sử của Mr Stach cũng cho thấy cái phần nhẹ nhàng, sáng sủa hơn của

Kafka. Trong

1 lần holyday, đi chơi với bồ, ông cảm thấy mình bịnh, vì cười nhiều

quá. Trong

những năm sau cùng của đời mình, ông gặp 1 cô gái ngồi khóc ở 1 công

viên, và cô

nàng nói với ông, là cô làm mất con búp bế. Thế là mỗi ngày ông viết

cho cô bé

1 lá thư, trong ba tuần lễ, lèm bèm về con búp bế bị mất. Với người

tình sau cùng,

Dora Diamant, rõ là ông tính lấy làm vợ. Cô này còn dụ ông trở lại được

với Do

Thái giáo.

Những giai

thoại trên chọc thủng hình ảnh 1 Kafka khắc khổ, qua tác phẩm của ông.

Mr Stach

còn vứt vô thùng rác [undermine] những cái nhìn có tính ước lệ

[conventional

views] về 1 Kakka như 1 nhà tiên tri của những tội ác kinh hoàng ghê

rợn

[atrocities] sẽ tới (ba chị/em của ông chết trong trại tập trung Nazi,

cũng như

hai bạn gái của ông). Trong những nhận xét về mục tiêu bài Do Thái, ông

mô tả 1 thế giới

như ông nhìn thấy nó, đầy nỗi cô đơn và những cá nhân con người bị bách

hại, nhưng

không phải 1 thế giới không có hy vọng.

*

Franz

Kafka:

Sáng chói bồn chồn

A definitive

biography of a rare writer

Một tiểu sử

chung quyết của 1 nhà văn hiếm, lạ.

Kafka: The

Years of Insight. By Reiner Stach. Princeton University Press;

682 pages; $35

and £24.95.

Vào năm

1915, một truyện ngắn được gọi là “Hóa Thân” được xuất bản ở 1 tạp chí

“bèo”

[small] của Đức. Nó kể câu chuyện một anh chàng bán hàng, một buổi sáng

thức

dậy thấy mình biến thành 1 con bọ khổng lồ. Tác giả, một nhân viên dân

sự trung lưu, làm việc tại Prague. Chưa tới 10 năm sau đó, ông mất, một

tác giả

ít được biết tới của ba cuốn tiểu thuyết và vài tác phẩm ngắn hơn.

Nhưng Hóa Thân

– có lẽ chỉ chừng 50 trang - sẽ hóa thân thành 1 con bọ khổng lồ, ấy

chết xin lỗi

- sẽ trở thành nguồn cảm hứng cho hằng hà tác phẩm - những chuyển thể

sân khấu, dàn

dựng kịch nghệ không làm sao đếm nổi, những luận án tiến sĩ thạc sĩ, và

hằng

hà những nhà văn tiếp theo. Hoá Thân,

và cùng với truyện ngắn đó, hai cuốn tiểu

thuyết, Vụ Án, và Tòa Lâu Đài,

đã đóng cứng vị trí của Kafka, như là một trong những nhà văn quan

trọng nhất của

thế kỷ 20.

Hình trên

báo giấy còn thấy được 1 con mắt của Kafka.

Note: Nervous brilliance,

tạm dịch, “sáng chói bồn chồn”.

Bỗng nhớ Cô Tư, “sáng chói, đen, và hơi khùng” [thực ra là, “đen, buồn

và hơi

khùng”]

Nhưng

cuốn

tiểu sử của Mr Stach cũng cho thấy cái phần nhẹ nhàng, sáng sủa hơn của

Kafka. Trong

1 lần holyday, đi chơi với bồ, ông cảm thấy mình bịnh, vì cười nhiều

quá. Trong

những năm sau cùng của đời mình, ông gặp 1 cô gái ngồi khóc ở 1 công

viên, và cô

nàng nói với ông, là cô làm mất con búp bế. Thế là mỗi ngày ông viết

cho cô bé

1 lá thư, trong ba tuần lễ, lèm bèm về con búp bế bị mất. Với người

tình sau cùng,

Dora Diamant, rõ là ông tính lấy làm vợ. Cô này còn dụ ông trở lại được

với Do

Thái giáo.

Những giai

thoại trên chọc thủng hình ảnh 1 Kafka khắc khổ, qua tác phẩm của ông.

Mr Stach

còn vứt vô thùng rác [undermine] những cái nhìn có tính ước lệ

[conventional

views] về 1 Kakka như 1 nhà tiên tri của những tội ác kinh hoàng ghê

rợn

[atrocities] sẽ tới (ba chị/em của ông chết trong trại tập trung Nazi,

cũng như

hai bạn gái của ông). Trong những nhận xét về mục tiêu bài Do Thái, ông

mô tả 1 thế giới

như ông nhìn thấy nó, đầy nỗi cô đơn và những cá nhân con người bị bách

hại, nhưng

không phải 1 thế giới không có hy vọng.

Franz Kafka

A definitive biography of a rare writer

Kafka: The Years of Insight. By Reiner

Stach. Princeton University Press; 682 pages; $35 and £24.95.

Buy from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk

IN 1915 a short story called “The Metamorphosis” (“Die Verwandlung”) was published in a small German

magazine. It told the story of Gregor Samsa, a salesman who wakes up

one morning to find that he has turned into an enormous bug. The

author, Franz Kafka, was a middle-ranking civil servant working in

Prague. He would die less than ten years later, a little-known author

of three novels and several shorter works. But “The

Metamorphosis”—perhaps 50 pages long—would go on to inspire countless

stage adaptations and doctoral theses and scores of subsequent writers.

The story, along with the novels “The Trial” and “The Castle”, ensured

Kafka’s place as one of the most important writers of the 20th century.

“Kafka: The Years of Insight” is the second volume of

Reiner Stach’s masterful biography of the author. The first dealt with

the years 1910 to 1915, when Kafka was a young man writing furiously

into the night while working 50-hour weeks. The second volume records

his burgeoning fame up until his death in an Austrian sanatorium at the

age of 40, after years of suffering from tuberculosis. (A third volume,

tracing his early years, is in the works.)

In these final years, from 1916 to 1924, Kafka receives

letters from quizzical bank managers asking him to explain his stories

(“Sir, You have made me unhappy. I bought your ‘Metamorphosis’ as a

present for my cousin, but she doesn’t know what to make of the

story”). He spends hours nagging away at his prose, only to rip it up,

throw it away and start again. He apparently denies being the author of

certain stories when asked by other invalids at a retreat. He has four

love affairs, mostly through letters, and spends much of his time away

from his cramped office at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute.

These are years of insight, but also of depression and illness.

Despite the gloom, this biography makes for an excellent

read. Mr Stach, a German academic, expertly presents Kafka’s struggles

with his work and health against the wider background of the first

world war, the birth of Czechoslovakia and the hyperinflation of the

1920s. Alert to the limits of biography, Mr Stach bases everything on

archival materials and, where possible, Kafka’s own view of events. He

is also wryly aware of the academic cottage industry that has sprung up

around Kafka’s work, hints of which had already emerged in his

lifetime. “You are so pure, new, independent...that one ought to treat

you as if you were already dead and immortal,” wrote one fan.

The picture that emerges is of a difficult, brilliant

man. In Mr Stach’s view, Kafka was “a neurotic, hypochondriac,

fastidious individual who was complex and sensitive in every regard,

who always circled around himself and who made a problem out of

absolutely everything”. A decision to visit a married woman, soon to be

his lover, takes him three weeks and 20 letters. When writing to his

first fiancée, he refers to himself in the third person and struggles

to evoke intimacy. Kafka makes decisions only to swiftly unmake them.

Other people irritate him. “Sometimes it almost seems to me that life

itself is what gets on my nerves,” he wrote to a friend.

But Mr Stach’s biography also shows Kafka’s lighter

side. On holiday with a mistress, he feels almost sick with laughter.

In the last years of his life he meets a crying young girl in a park

who explains that she has lost her doll. He then proceeds to write her

a letter a day for three weeks from the perspective of the doll,

recounting its exploits. With his final mistress, Dora Diamant, Kafka

has no doubt that he wants to marry her. She even inspires him to

recover his interest in Judaism.

Such anecdotes pierce the austere image left by Kafka’s

work. Mr Stach also effectively undermines conventional views of Kafka

as a prophet of the atrocities to come (his three sisters died in Nazi

concentration camps, as did two of his mistresses). A frequent target

of anti-Semitic remarks, Kafka depicted the world as he saw it, full of

lonely and persecuted individuals, but not one without hope.

|

|