|

Ghi

|

Death in rue Catinat

Go and try

to disprove death, death will disprove you.

- TURGENEV

On 5 January

1952 the New York Times

reported that General de Lattre had been operated on in

Paris: 'Neither the nature of his illness nor of the operation has been

disclosed.' By 11 January the heroic soldier was dead; it was a time of

mourning in Vietnam, as a letter sent home by Nancy Baker shows:

For

about 4

weeks the latter part of January and the first of February, the local

French

and Vietnamese officials and the Diplomatic Corps were in

mourning for the

death of de Lattre. Not that I

was in agreement for that long length of time of mourning, we still had

a very

enjoyable time staying home in the evenings, reading, or have small

dinners.'

With de

Lattre gone, hope died that the French could win the war in Vietnam.

The United

States and France held opposed views on the country's future, and if

the US

State Department did not press France hard

this was only because it felt that France might throw in the towel, to

stem the

loss of its best sons. There were real divisions in the American

legation in

Saigon also. On the one hand Ambassador Heath was a genuine supporter

of the

French leadership symbolized by de Lattre. Edmund Gullion thought the

French

were wrong and that they were not serious about independence. He and

Robert Blum

were strongly against the survival of colonialism and in favor of

building up a

nationalist army. They both advocated ways of winning the war which the

French

authorities found unacceptable.

Blum, like

Pyle in The Quiet American, was

looking for a third force to capture the nationalist interest of the

Vietnamese

people. He felt that only if the Vietnamese were fighting for democracy

and independence

would they begin to take a powerful personal interest in defeating the

communist Vietminh. Without a third force, he and Gullion both

believed the French could not succeed. As Blum said:

We

wanted to

strengthen the ability of the French to protect the area against

Communist

infiltration and invasion, and we wanted to capture the nationalist

movement

from the Communists by encouraging the national aspirations of the

local populations

and increasing popular support of their governments. We knew that the

French

were unpopular! that the war that had been going on since I946 was not

only nationalist

revolt against them but was an example of the awakening

self-consciousness of

the peoples of Asia who were trying to break loose from domination by

the Western

world.

Blum wanted

the United States to be looked upon as a friend to a new nation, not as

a

supporter of colonialism (that was an anathema to the Americans). After

visiting

Vietnam in I951, Congressman John F. Kennedy went home to preach the

gospel of

those forward-looking Americans in the legation. Speaking of how

America had

allied itself to the desperate effort of the French regime to hang on

to the

remnants of an empire, Kennedy concluded: 'the French cannot succeed in

Indochina

without giving concessions necessary to make the native army a reliable

and

crusading force. ' Emperor Bao

Dai feared that if the Vietnamese army were expanded into a nationalist

army,

it might defect en masse to the Vietminh. His tragedy

was that he was expressing

a truth that initially looked like cynicism.

Because Bao Dai

proved so disappointing the Americans felt they had to find someone who

represented the new nationalism, someone who opposed the French,

someone

without the taint of colonialist power, who was also strongly opposed

to the

communist Vietminh. Thus Colonel The became significant.

At the time that

Greene was visiting Vietnam and beginning to writeThe Quiet American, Colonel

The had not yet become important to the Americans. They knew he was

small beer,

but in the early days of his revolt from the Cao Dai his statements

expressed

his opposition to both the French and the communists. It was only

later, after

Dien Bien Phu in 1954 when the French were in the process of leaving

Vietnam,

that the Americans decided on their third force figure - the Catholic

strong

man Ngo Dinh Diem, who had spent much of the war in a monastery in New

Jersey.

Thé then came into his own by joining forces with Diem. He was brought

back out

of the jungle to support Diem by Colonel Lansdale with the help of CIA

money.

To the French The was a murderous reptile: to the ordinary Vietnamese a

romantic hero.

Norman

Sherry: The Life of Graham Greene Volume

2: 39-55

Ways of Escape

Ngô Đình Diệm

mang trong ông huyền thoại về một con người Mít hoàn toàn Mít, không

đảng phái,

không Đệ Tam, Đệ Tứ, không Việt gian bán nước cho Tây, cho Tầu, cho

Liên Xô.

Cùng với huyền thoại về một vĩ nhân Mít hoàn toàn Mít đó, là huyền

thoại về một

lực lượng thứ ba, như Gấu đã từng lèm bèm nhiều lần, đây là đề tài của

cuốn Người

Mỹ Trầm Lặng của Greene. Fowles khuyên anh chàng Mẽo ngây thơ, trầm

lặng, mang

Phượng về Mẽo, quên mẹ nó lực lượng thứ ba đi: lịch sử diễn ra đúng như

vậy, nước

Mẽo đã dang tay đón bao nhiêu con người Miền Nam bị cả hai bên bỏ rơi,

những cô

Phượng ngày nào. (1)

Trong "Tiểu sử

của Graham Greene", Tập 3, có cái tiểu chú, về lần GG phỏng vấn Tổng

Thống Diệm [bài phỏng vấn thấy ghi, ở cuối sách, 16.8.1982, đúng sinh nhật GCC, nhưng phỏng vấn Diệm ngày

nào, không], ông có hỏi Diệm là tại sao cho Thế

trở về,

khi ông ta trách nhiệm về vụ giết rất nhiều người của chính ông ta [ám

chỉ vụ

Thế chủ mưu giết thường dân tại Catinat] Greene nhớ là, Diệm bật cười

lớn, và nói:

“Peut-être, peut-être” [Có thể, có thể].

Cả cuốn "Người

Mỹ Trầm Lặng" xoay quanh nhân vật Thế, “Lực lượng thứ ba”, không có Thế

[LLTB] là

không có nó. Chúng ta tự hỏi, liệu có LLTB?

Because Bao

Dai proved so disappointing the Americans felt they had to find someone

who

represented the new nationalism, someone who opposed the French,

someone

without the taint of colonialist power, who was also strongly opposed

to the

communist Vietminh. Thus Colonel The became significant. At the time

that

Greene was visiting Vietnam and beginning to write The Quiet American,

Colonel

The had not yet become important to the Americans. They knew he was

small beer,

but in the early days of his revolt from the Cao Dai his statements

expressed his

opposition to both the French and the communists. It was only later,

after Dien

Bien Phu in 1954 when the French were in the process of leaving

Vietnam, that

the Americans decided on their third force figure - the Catholic strong

man

Ngo Dinh Diem, who had spent much of the war in a monastery in New

Jersey. Thé

then came into his own by joining forces with Diem. He was brought back

out of

the jungle to support Diem by Colonel Lansdale with the help of CIA

money. To

the French The was a murderous reptile: to the ordinary Vietnamese a

romantic

hero. Howard Simpson, an American writer in Saigon, described

overhearing an

'incongruous melodrama' (his words) involving General Nguyen Van Vy, a

pro-French

Bao Dai loyalist and chief of staff of the Vietnamese army, and Colonel

The:

Cao Dai

general Trinh Minh The, in civilian clothes, is lecturing Vy while

armed

members of The's newly formed pro-Diem 'Revolutionary Committee' have

taken up

positions by the doors and windows...

General Vy

is being asked to read a prepared statement calling for an end to

French

interference in Vietnamese affairs, repudiating Bao Dai, and pledging

his

loyalty to Ngo Dinh Diem. Vy is responding to The's harangue in a low

voice,

trying to argue his case. The veins on The's forehead are standing out

... Suddenly

The pulls a Colt .45 from his belt, strides forward, and puts its

muzzle to

Vy's temple. The pushes Vy to the microphone, the

heavy automatic pressed tight against the

general's short-cropped gray hair. I wince, waiting for the Colt's

hammer to fall.

The

repetitive clicking of a camera is the only sound in the tense silence

... Vy

begins to read the text into the mike, the paper shaking in his hands.

His face

is ashen, and perspiration stains his collar. The complains he can't

hear and

demands that Vy speak louder. When Vy finishes, The puts his automatic

away.

General relief sweeps the room."

*

The's

influence is central to the plot of The

Quiet American. He is the

catalyst who reveals Pyle's 'special

duties” '.

The's desperate actions in the novel are based on historical fact.

Greene also

asserts, both in the novel and in his non-fictional writing, that the

CIA was

involved with The, providing him with the material to carry out

nefarious actions.

This is what so scandalized Liebling in the New Yorker: 'There is a

difference

. . . between calling your over-successful offshoot a silly ass and

accusing

him of murder.’

In his

dedication to Rene Berval and Phuong, Greene mentioned that he had

rearranged

historical events: 'the big bomb near the Continental preceded and did

not

follow the bicycle bombs. I have no scruples about such small

changes.'

Trong cuốn

tiểu sử của Greene, thì “Lực Lượng Thứ Ba”, anh Xịa ngây thơ gặp, là

Trình Minh

Thế. Greene không ưa TMT, và không tin ông làm được trò gì. Nhưng chỉ

đến khi

TMT bị Diệm thịt, thì ông mới thay đổi thái độ, như trong cái thư mở ra

"Người Mỹ

Trầm Lặng" cho thấy.

Theo GCC, cuốn NMTL được

phát sinh, là từ cái tên Phượng, đúng như

trong tiềm

thức của Greene mách bảo ông. (1)

Cả

cuốn truyện

là từ đó mà ra. Và nó còn tiên tri ra được cuộc xuất cảng người phụ nữ

Mít cả

trước và sau cuộc chiến, đúng như lời anh ký giả Hồng Mao ghiền khuyên

Pyle, mi

hãy quên “lực lượng thứ ba” và đem Phượng về Mẽo, quên cha luôn cái xứ

sở khốn

kiếp Mít này đi!

The Life of

Graham Greene

Volume 2:

1939-1955

Norman

Sherry

Note: Một

trong những em Phượng, đi đúng những ngày 30 Tháng Tư, 1975, và là 1

trong những

nhà văn nữ hàng đầu của Miền Nam trước 1975, khi Gấu tới trại tị nạn,

gửi thư cầu

cứu, đã than giùm, anh đi trễ quá, Miền Biển Động hết động rồi.

Sao không ở

luôn với số phận xứ Mít [ở với VC?], chắc em P. của 1 anh Mẽo Pyle nào

đó, tính khuyên Gấu?

(1)

"Phuong,"

I said – which means Phoenix, but nothing nowadays is fabulous and

nothing

rises from its ashes. "Phượng", tôi nói, "Phượng có nghĩa là Phượng

hoàng, nhưng những ngày này chẳng có chi là huyền hoặc, và chẳng có gì

tái sinh

từ mớ tro than của loài chim đó":

Quả có sự

tái sinh từ mớ tro than của loài chim đó!

Cuộc xuất cảng Phượng sau 1975,

là cả 1

cái nguồn nuôi nước Mít, theo nghĩa thê thảm nhất, hoặc, cao cả nhất

[Hãy nghĩ

đến những gia đình Miền Nam phải cho con gái đi làm dâu Đại Hàn,

thí dụ,

để sống sót VC]

Ways of Escape

Kevin

Ruane, The

Hidden

History of Graham Greene’s Vietnam War: Fact, Fiction and The Quiet

American, History,

The Journal of the Historical Association, ấn hành bởi Blackwell

Publishing

Ltd., tại Oxford, UK và Malden, MA., USA, 2012, các trang 431-452.

LỊCH SỬ ẨN

TÀNG CỦA CHIẾN TRANH VIỆT NAM CỦA GRAHAM GREENE:

SỰ KIỆN,

HƯ CẤU VÀ QUYỂN THE QUIET AMERICAN (NGƯỜI MỸ TRẦM LẶNG)

Ngô Bắc dịch

ĐẠI Ý:

Nơi

trang có minh họa đằng trước trang nhan đề của quyển tiểu

thuyết đặt khung cảnh tại Việt Nam của mình, quyển The Quiet

American,

xuất bản năm 1955, Graham Greene đã nhấn mạnh rằng ông viết “một truyện

chứ

không phải một mảnh lịch sử”, song vô số các độc giả trong các thập

niên kế

tiếp đã không đếm xỉa đến các lời cảnh giác này và đã khoác cho tác

phẩm sự

chân thực của lịch sử. Bởi viết ở ngôi thứ nhất, và bởi việc gồm

cả sự

tường thuật trực tiếp (được rút ra từ nhiều cuộc thăm viếng của ông tại

Đông

Dương trong thập niên 1950) nhiều hơn những gì có thể được tìm thấy

trong bất

kỳ tiểu thuyết nào khác của ông, Greene đã ước lượng thấp tầm mức theo

đó giới

độc giả của ông sẽ lẫn lộn giữa sự thực và hư cấu. Greene đã

không chủ

định để quyển tiểu thuyết của ông có chức năng như sử ký, nhưng đây là

điều đã

xảy ra. Khi đó, làm sao mà nó đã được ngắm nhìn như lịch sử? Để

trả lời

câu hỏi này, phần lớn các nhà bình luận quan tâm đến việc xác định

nguồn khởi

hứng trong đời sống thực tế cho nhân vật Alden Pyle, người Mỹ trầm lặng

trong

nhan đề của quyển truyện, kẻ đã một cách bí mật (và tai họa) phát triển

một Lực

Lượng Thứ Ba tại Việt Nam, vừa cách biệt với phe thực dân Pháp và phe

Việt Minh

do cộng sản cầm đầu. Trong bài viết này, tiêu điểm ít nhắm vào

các nhân

vật cho bằng việc liệu người Mỹ có thực sự bí mật tài trợ và trang bị

vũ khí

cho một Lực Lượng Thứ Ba hay không. Ngoài ra, sử dụng các thư tín

và nhật

ký không được ấn hành của Greene cũng như các tài liệu của Bộ Ngoại Vụ

[Anh

Quốc] mới được giải mật gần đây chiếu theo Đạo Luật Tự Do Thông Tin Của

Vương

Quốc Thống Nhất (UK Freedom of Information Act), điều sẽ được nhìn thấy

rằng

người Anh cũng thế, đã có can dự vào mưu đồ Lực Lượng Thứ Ba sau lưng

người

Pháp và rằng bản thân Greene đã là một thành phần của loại dính líu

chằng chịt

thường được tìm thấy quá nhiều trong các tình tiết của các tiểu thuyết

của ông.

Source

Note: Nguồn

của bài viết này, đa số lấy từ “Ways of Escape” của Graham Greene.

Và cái sự lầm

lẫn giữa giả tưởng và lịch sử, ở đây, là do GG cố tình, như chính ông

viết:

Như vậy là đề tài Người Mỹ

Trầm Lặng đến với tôi, trong

cuộc “chat”, về “lực lượng thứ ba” trên con đường đồng bằng [Nam Bộ] và

những

nhân vật của tôi bèn lẵng nhẵng đi theo, tất cả, trừ 1 trong số họ, là

từ tiềm

thức. Ngoại lệ, là Granger, tay ký giả Mẽo. Cuộc họp báo ở Hà Nội, có

anh ta,

được ghi lại, gần như từng lời, từ nhật ký của tôi, vào thời kỳ đó.

Có lẽ cái chất phóng sự của Người

Mỹ Trầm Lặng nặng “đô” hơn, so với bất

cứ cuốn tiểu thuyết nào mà tôi đã viết. Tôi chơi lại cách đã dùng, trong

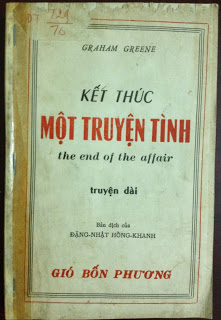

Kết

Thúc một Chuyện Tình, khi sử dụng ngôi thứ nhất, và cách chuyển

thời

[time-shift], để bảo đảm chất phóng sự. Cuộc họp báo ở Hà Nội không

phải là thí

dụ độc nhất của cái gọi là phóng sự trực tiếp. Tôi ở trong 1 chiến đấu

cơ (tay

phi công đếch thèm để ý đến lệnh của Tướng de Lattre, khi cho tôi tháp

tùng),

khi nó tấn công những điểm có Vẹm, ở trong toán tuần tra của lực lượng

Lê

Dương, bên ngoài Phát Diệm. Tôi vẫn còn giữ nguyên hình ảnh, 1 đứa bé

chết, bên

cạnh bà mẹ, dưới 1 con mương. Những vết đạn cực nét làm cho cái chết

của hai mẹ

con nhức nhối hơn nhiều, so với cuộc tàn sát làm nghẹt những con kinh

bên ngoài

nhà thờ Phát Diệm.

Tôi trở lại Đông Dương lần thứ tư và là lần cuối cùng vào năm 1955, sau

cú thất

trận của Tẩy ở Bắc Việt, và với tí khó khăn, tôi tới được Hà Nội, một

thành phố

buồn, bị tụi Tẩy bỏ rơi, tôi ngồi chơi chai bia cuối cùng [may quá,

cũng bị tụi

Tẩy] bỏ lại, trong 1 quán cà phê, nơi tôi thường tới với me-xừ Dupont.

Tôi cảm

thấy rất bịnh, mệt mỏi, tinh thần sa sút. Tôi có cảm tình với tụi thắng

trận

nhưng cũng có cảm tình với tụi Tẩy [làm sao không!] Những cuốn sách của

những

tác giả cổ điển Tẩy, thì vưỡn thấy được bày ở trong 1 tiệm sách nhỏ,

chuyên bán

sách cũ, nơi tôi và ông bạn nói trên cùng lục lọi, mấy năm về trước,

nhưng 100

năm văn hóa thằng Tây mũi lõ thì đã theo tín hữu Ky Tô, nhà quê, Bắc

Kít, bỏ

chạy vô Miền Nam. Khách sạn Metropole, nơi tôi thường ở, thì nằm trong

tay Phái

Đoàn Quốc Tế [lo vụ Đình Chiến. NQT]. Mấy anh VC đứng gác bên ngoài tòa

nhà,

nơi Tướng De Lattre đã từng huênh hoang hứa nhảm, ‘tớ để bà xã ở lại,

như là 1

bằng chứng nước Tẩy sẽ không bao giờ, không bao giờ….’

Ngày lại qua ngày, trong khi

tôi cố tìm cách gặp Bác Hát….

Graham

Greene: Ways of Escape

GCC đang hăm

he/hăm hở dịch tiếp đoạn, Greene làm “chantage” - Day after day passed

while I tried to bully my way into the presence of Ho Chi Minh, I

don't

know why my blackmail succeeded, but I was summoned suddenly to take

tea with

Ho Chi Minh meetin -, để Bác hoảng, phải cho gặp mặt.

*

Đỉnh cao chói lọi

Sinh nhạt Bác

Viên gạch Bác

Một

số tiết lộ về cuộc chiến từ tài liệu CIA

Greene viết Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng, là

cũng từ nguồn này, qua lần gặp gỡ một anh Xịa, khi đi thăm Le Roy, trên

đường trở về Sài Gòn. (1)

(1)

Giấc mơ lớn của Mẽo,

từ đó, cái mầm của Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng bật ra, khi Greene, trên đường trở về Sài Gòn, sau khi qua một

đêm với tướng Leroy, Hùm Xám Bến Tre, như ông viết, trong Tam thập

lục kế tẩu vi thượng sách, Ways of Escape.

"Cách đây chưa đầy một

năm, [Geeene viết năm 1952], tôi đã từng tháp tùng Le Roy, tham quan

vương quốc sông rạch, trên chiến thuyền của ông ta. Lần này, thay vì

chiến thuyền, thì là du thuyền, thay vì dàn súng máy ở hai bên mạn

thuyền, thì là chiếc máy chạy dĩa nhạc, và những vũ nữ.

Bản nhạc đang chơi, là từ

phim Người Thứ Ba, như để vinh danh tôi.

Tôi dùng chung phòng ngủ

với một tay Mẽo, tùy viên kinh tế, chắc là CIA, [an American attached

to an economic aid mission - the members were assumed by the French,

probably correctly, to belong to the CIA]. Không giống Pyle,

thông minh hơn, và ít ngu hơn [of less innocence]. Anh ta bốc phét,

suốt trên đường từ Bến Tre về Sài Gòn, về sự cần thiết phải tìm cho ra

một lực lượng thứ ba ở Việt Nam.

Cho tới lúc đó, tôi chưa

bao giờ cận kề với giấc mộng lớn của Mẽo, về những áp phe ma quỉ, tại Đông

phương, như là nó đã từng, tại Phi Châu.

Trong Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng, Pyle nhắc tới câu của tay ký giả York

Harding – cái mà phía Đông cần, là một Lực Lượng Thứ Ba – anh ta xem có

vẻ ngây thơ, nhưng thực sự đây chính là chính sách của Mẽo.

Người Mẽo tìm kiếm một nhà lãnh đạo Việt Nam không tham nhũng, hoàn

toàn quốc gia, an incorruptible, purely nationalist Vietnamese leader,

người có thể kết hợp, unite, nhân dân Việt Nam, và tạo thành một thế

đứng, một giải pháp, đối với Việt Minh CS."

Greene rất chắc chắn, về nguồn của

Người Mỹ trầm lặng:

"Như vậy, đề tài NMTL tới

với tôi, trong cuộc nói chuyện trên, về 'lực lượng thứ ba', trên đường

vượt đồng bằng sông Cửu Long, và từ đó, những nhân vật theo sau, tất

cả, [trừ một, Granger], là từ tiềm thức bật ra."

Ways of escape

NKTV: 30.4.2912_1

Trong cuốn

tiểu sử của Greene, thì “Lực Lượng Thứ Ba”, anh Xịa ngây thơ gặp, là

Trình Minh

Thế. Greene không ưa TMT, và không tin ông làm được trò gì. Nhưng chỉ

đến khi

TMT bị Diệm thịt, thì ông mới thay đổi thái độ, như trong cái thư mở ra

"Người Mỹ

Trầm Lặng" cho thấy.

Theo GCC, cuốn NMTL được

phát sinh, là từ cái tên Phượng, đúng như

trong tiềm

thức của Greene mách bảo ông.

Cả

cuốn truyện

là từ đó mà ra. Và nó còn tiên tri ra được cuộc xuất cảng người phụ nữ

Mít cả

trước và sau cuộc chiến, đúng như lời anh ký giả Hồng Mao ghiền khuyên

Pyle, mi

hãy quên “lực lượng thứ ba” và đem Phượng về Mẽo, quên cha luôn cái xứ

sở khốn

kiếp Mít này đi!

The Life of

Graham Greene

Volume 2:

1939-1955

Norman

Sherry

Note: Một

trong những em Phượng, đi đúng những ngày 30 Tháng Tư, 1975, và là 1

trong những

nhà văn nữ hàng đầu của Miền Nam trước 1975, khi Gấu tới trại tị nạn,

gửi thư cầu

cứu, đã than giùm, anh đi trễ quá, Miền Biển Động hết động rồi.

Sao không ở luôn

với số phận xứ Mít [ở với VC?]

"Phuong,"

I said – which means Phoenix, but nothing nowadays is fabulous and

nothing

rises from its ashes. "Phượng", tôi nói, "Phượng có nghĩa là Phượng

hoàng, nhưng những ngày này chẳng có chi là huyền hoặc, và chẳng có gì

tái sinh

từ mớ tro than của loài chim đó":

Quả có sự

tái sinh từ mớ than của loài chim đó! Cuộc xuất cảng Phượng sau 1975,

là cả 1

cái nguồn nuôi nước Mít, theo nghĩa thê thảm nhất, hoặc, cao cả nhất

[Hãy nghĩ

đến những gia đình Miền Nam phải cho con gái đi làm dâu Đại Hàn,

thí dụ,

để sống sót VC]

Võ tướng

quân về Trời

Greene đi tuần tra cùng lính Pháp tại Phát Diệm

So the

subject of The Quiet American came to

me, during that talk of a 'third force' on the road through the delta,

and my

characters quickly followed, all but one of them from the unconscious.

The

exception was Granger, the American newspaper correspondent. The press

conference in Hanoi where he figures was recorded almost word for word

in my

journal at the time. Perhaps there is more direct reportage in The Quiet American than in any other

novel I have written. I had determined to employ again the experience I

had

gained with The End of the Affair in

the use of the first person and the time-shift, and my choice of a

journalist

as the 'I' seemed to me to justify the use of reportage. The press

conference

is not the only example of direct reporting. I was in the dive-bomber

(the

pilot had broken an order of General de Lattre by taking me) which

attacked the

Viet Minh post and I was on the patrol of the Foreign Legion paras

outside Phat

Diem. I still retain the sharp image of the dead child couched in the

ditch

beside his dead mother. The very neatness of their bullet wounds made

their death

more disturbing than the indiscriminate massacre in the canals around.

I went back

to Indo-China for the fourth and last time in 1955 after the defeat of

the French

in the north, and with some difficulty I reached Hanoi - a sad city,

abandoned

by the French, where I drank the last bottle of beer left in the cafe

which I

used to frequent with Monsieur Dupont. I was feeling very ill and tired

and

depressed. I sympathized with the victors, but I sympathized with the

French

too. The French classics were yet on view in a small secondhand

bookshop which

Monsieur Dupont had rifled a few years back, but a hundred years of

French

civilization had fled with the Catholic peasants to the south. The

Metropole

Hotel where I used to stay was in the hands of the International

Commission.

Viet Minh sentries stood outside the building where de Lattre had made

his

promise, 'I leave you my wife as a symbol that France will never, never

... '

Day after day passed while I tried to bully my way into the presence of

Ho Chi

Minh. It was the period of the crachin

and my spirits sank with the thin day-long drizzle of warm rain. I told

my

contacts I could wait no longer - tomorrow I - would return to what was

left of

French territory in the north.

I don't know

why my blackmail succeeded, but I was summoned suddenly to take tea

with Ho Chi

Minh, and now I felt too ill for the meeting. There was only one thing

to be

done. I went back to an old Chinese chemist's shop in the rue des

Voiles which

I had visited the year before. The owner, it was said, was 'the

Happiest Man in

the World’. There I was able to smoke a few pipes of opium while the

mah-jong

pieces rattled like gravel on a beach. I had a passionate desire for

the impossible

- a bottle of Eno's. A messenger was dispatched and before the pipes

were

finished I received the impossible. I had drunk the last bottle of beer

in

Hanoi. Was this the last bottle of Eno's? Anyway the Eno's and the

pipes took

away the sickness and the inertia and gave me the energy to meet Ho Chi

Minh at

tea.

Of those

four winters which I passed in Indo-China opium has left the happiest

memory,

and as it played an important part in the life of Fowler, my character

in The Quiet American, I add a few memories

from my journal concerning it, for I am reluctant to leave Indo-China

for ever

with only a novel to remember it by.

Graham Greene: Ways of Escape

Như vậy là đề

tài Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng đến với tôi,

trong cuộc “chat”, về “lực lượng thứ ba” trên con đường đồng bằng [Nam

Bộ] và

những nhân vật của tôi bèn lẵng nhẵng đi theo, tất cả, trừ 1 trong số

họ, là từ

tiềm thức. Ngoại lệ, là Granger, tay ký

giả Mẽo. Cuộc họp báo ở Hà Nội, có anh ta, được ghi lại, gần như từng

lời, từ

nhật ký của tôi, vào thời kỳ đó.

Có lẽ cái chất

phóng sự của Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng nặng “đô”

hơn, so với bất cứ cuốn tiểu thuyết nào mà tôi đã viết. Tôi chơi lại

cách đã dùng,

trong Kết Thúc một Chuyện Tình, khi sử

dụng ngôi thứ nhất, và cách chuyển thời [time-shift], để bảo đảm chất

phóng sự.

Cuộc họp báo ở Hà Nội không phải là thí dụ độc nhất của cái gọi là

phóng sự trực tiếp. Tôi

ở trong 1 chiến đấu cơ (tay phi công đếch thèm để ý đến lệnh của Tướng

de

Lattre, khi cho tôi tháp tùng), khi nó tấn công những điểm có Vẹm, ở

trong toán

tuần tra của lực lượng Lê Dương, bên ngoài Phát Diệm. Tôi vẫn còn giữ

nguyên hình

ảnh, 1 đứa bé chết, bên cạnh bà mẹ, dưới 1 con mương. Những vết đạn cực

nét làm

cho cái chết của hai mẹ con nhức nhối hơn nhiều, so với cuộc tàn sát

làm

nghẹt những con kinh bên ngoài nhà thờ Phát Diệm.

Tôi trở lại Đông

Dương lần thứ tư và là lần cuối cùng vào năm 1955, sau cú thất trận của

Tẩy ở Bắc

Việt, và với tí khó khăn, tôi tới được Hà Nội...

Ways of Escape

Cuốn này mua

từ hồi nào, bi giờ mới thấy, sau khi lục lọi, cố tìm cuốn Phân tâm học về

Lửa của Bachelard, để đọc lại. Coi lửa của Bachelard có tí nhân ái

nào

không so với lửa của QD, ông anh ruột của Thầy Phúc.

Hà, hà!

Cuốn này, nằm trong 1 chùm

mà 1 em nữ phê bình gia phán, trung tâm điểm

của khá nhiều cái viết của Greene [Brighton

Rock, The Power and the

Glory, The

Heart of the matter] là tự tử, mà theo như Ky Tô giáo, đây là

tội nặng

nhất. Và

nhà văn bèn phịa ra 1 câu để bào chữa cho quan điểm của ông: Tui là tác

giả, và

tác giả này thì là một tín hữu Kytô, “I am an author who is a Catholic”

Ways of escape: Tam

thập lục kế, tẩu vi

thượng sách!

Hồi ký

của Greene. Những đoạn viết về Việt Nam thật tuyệt.

Trở lại

Anh, Greene nhớ Việt Nam

quá và đã

mang theo cùng với ông một cái tẩu hít tô phe, như là một kỷ niệm tình

cảm: cái

tẩu mà ông đã hít lần chót, tại một tiệm hít ngoài đường Catinat. Tay chủ, người Tầu hợp với ông, và ông đã đi vài

đường

dậy tay này vài câu tiếng Anh. Tới ngày rời Việt Nam,

tay chủ tiệm hít bèn giúi vào

tay Greene cái tẩu. Cây gậy thiêng nằm trên một cái dĩa tại căn phòng

của

Greene, ở Albany,

bị sứt mẻ tí tí, do di chuyển, đúng là một thần vật cổ, của những ngày

hạnh

phúc.

Lần

thăm Việt Nam cuối, chàng

[Greene] hít nhiều hơn lệ thường: thường, nghĩa là ba hoặc bốn bi,

nhưng chỉ

riêng trong lần cuối này, ở Sài Gòn, trong khi chờ đợi một tờ visa

khác, tiếu

lâm thay, của Vi Xi, chàng "thuốc" chàng đến bất tri bất giác, he

smoked himself inerte.

Trong

những lần trước, thường

xuyên là với những viên chức Tây, chàng hít không quá hai lần trong một

tuần.

Lần này, một tuần hít ba lần, mỗi lần trên mười bi. Ngay cả hít nhiều

như thế

cũng chẳng đủ biến chàng thành ghiền. Ghiền, là phải hít trên trăm bi

một ngày.

Norman Sherry: Tiểu sử Greene

Trong

Ba Mươi Sáu Chước, Tẩu

Vi Thượng Sách, Ways of escape, một dạng

hồi nhớ văn học, Greene cho biết, đúng là một cơ may, chuyện ông chết

mê chết

mệt xứ Đông Dương. Lần thứ nhất viếng thăm, ông chẳng hề nghĩ, mình sẽ

đẻ ra

được một cuốn tiểu thuyết thật bảnh, nhờ nó. Một người bạn cũ của ông,

từ hồi

chiến tranh, lúc đó là Lãnh sự tại Hà

Nội, nơi một cuộc chiến tranh khác đang tiến diễn và hầu như hoàn toàn

bị bỏ

quên bởi báo chí Anh. Do đó, sau Malaya,

ông

bèn nháng qua Việt Nam thăm bạn, chẳng hề nghĩ, vài năm sau, sẽ

trải

qua tất cả những mùa đông của ông ở đây.

"Tôi nhận thấy, Malaya

'đần' như một người đàn bà đẹp đôi khi 'độn'. Người ở đó thường nói,

'Bạn phải

thăm xứ xở này vào thời bình', và tôi thật tình muốn vặc lại, 'Nhưng tớ

chỉ

quan tâm tới cái xứ sở đần độn này, khi có máu'. Không có máu, nó trơ

ra với

vài câu lạc bộ Anh, với một dúm xì căng đan nho nhỏ, nằm tênh hênh chờ

một tay

Maugham nào đó mần báo cáo về chúng."

"Nhưng

Đông Dương, khác

hẳn. Ở đó, tôi nuốt trọn bùa yêu, ngải lú, tôi cụng ly rượu tình với

mấy đám sĩ

quan Lực Lượng Lê Dương, mắt tay nào cũng sáng lên, khi vừa nghe nhắc

đến hai

tiếng Sài Gòn, hay Hà Nội."

Và bùa

yêu ép phê liền tù tì,

tôi muốn nói, giáng cú sét đánh đầu tiên của nó, qua những cô gái mảnh

khảnh,

thanh lịch, trong những chiếc quần lụa trắng, qua cái dáng chiều mầu

thiếc xà

xuống cánh đồng lúa trải dài ra mãi, đây đó là mấy chú trâu nước nặng

nề trong

cái dáng đi lảo đảo hai bên móng vốn có tự thời nguyên thuỷ của loài

vật này,

hay là qua mấy tiệm bán nước thơm của người Tây ở đường Catinat, hay

trong

những sòng bài bạc của người Tầu ở Chợ Lớn, nhưng trên hết, là qua cái

cảm giác

bi bi hài hài, trớ trêu làm sao, và cũng

rất ư là phấn chấn hồ hởi mà một dấu báo của hiểm nguy mang đến cho du

khách

với cái vé khứ hồi thủ sẵn ở trong túi: những tiệm ăn bao quanh bằng

những hàng

dây kẽm gai nhằm chống lại lựu đạn, những vọng gác cao lênh khênh dọc

theo

những con lộ nơi đồng bằng Nam Bộ với những lời cảnh báo thật là kỳ kỳ

[bằng

tiếng Tây, lẽ dĩ nhiên]: "Nếu bạn bị tấn công, và bị bắt giữ trên đường

đi, hãy báo liền lập tức cho viên sếp đồn quan trọng đầu tiên".

Dịp đó,

tôi ở hai tuần, và

tranh thủ tối đa, tới giây phút cuối cùng, cái giây phút không thể tha

thứ ,

"the unforgiving minute". Hà Nội cách Sài Gòn bằng London

xa Rome,

nhưng

ngoài chuyện ăn ngủ... ở cả hai thành phố, tôi còn ban cho mình những

chuyến tham

quan nơi đồng bằng Nam Bộ, tới những giáo phái lạ lùng như Cao Đài mà

những ông

thánh của nó bao gồm Victor Hugo, Christ, Phật, và Tôn Dật Tiên.

Ways of

escape

Liệu

giấc mơ về một cuộc

cách mạng, thỏa mãn giấc mơ như lòng chúng ta

thèm

khát tương lai, của TTT, có gì liên can tới ‘lực lượng thứ ba’, vốn là

một giấc

mơ lớn, của Mẽo, nằm trong hành trang của Pyle, [Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng

],

khi tới Việt Nam.

Giấc

mơ lớn của Mẽo, từ đó, cái mầm của Người Mỹ Trầm

Lặng bật

ra,

khi Greene, trên đường trở về Sài Gòn, sau khi qua một đêm với tướng

Leroy, Hùm

Xám Bến Tre, như ông viết, trong Tam thập lục kế tẩu

vi thượng

sách, Ways of

Escape.

"Cách

đây chưa đầy một năm, [Geeene viết năm 1952], tôi đã từng tháp

tùng

Le Roy, tham quan vương quốc sông rạch, trên chiến thuyền của ông ta.

Lần này,

thay vì chiến thuyền, thì là du thuyền, thay vì dàn súng máy ở hai bên

mạn thuyền,

thì là chiếc máy chạy dĩa nhạc, và những vũ nữ.

Bản

nhạc đang chơi, là từ phim Người Thứ Ba, như để vinh danh

tôi.

Tôi

dùng chung phòng ngủ với một tay Mẽo, tùy viên kinh tế, chắc là

CIA, [an

American attached to an economic aid mission - the members were assumed

by the

French, probably correctly, to belong to the CIA]. Không giống

Pyle,

thông minh hơn, và ít ngu hơn [of less innocence]. Anh ta bốc phét,

suốt trên

đường từ Bến Tre về Sài Gòn, về sự cần thiết phải tìm cho ra một lực

lượng thứ

ba ở Việt Nam.

Cho tới

lúc đó, tôi chưa giờ cận kề với giấc mộng lớn của Mẽo, về những

áp phe

ma quỉ, tại Đông phương, như là nó đã từng, tại Phi Châu.

Trong Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng, Pyle nhắc tới câu của tay ký giả York

Harding –

cái mà phía Đông cần, là một Lực Lượng Thứ Ba – anh ta xem có vẻ ngây

thơ,

nhưng thực sự đây chính là chính sách của Mẽo. Người Mẽo tìm kiếm một

nhà lãnh

đạo Việt Nam không tham nhũng, hoàn toàn quốc gia, an incorruptible,

purely

nationalist Vietnamese leader, người có thể kết hợp, unite, nhân dân

Việt Nam,

và tạo thành một thế đứng, một giải pháp, đối với Việt Minh CS.

Greene rất chắc chắn, về nguồn của Người Mỹ trầm lặng:

"Như vậy, đề tài NMTL tới với tôi, trong cuộc nói chuyện trên, về 'lực

lượng

thứ ba', trên đường vượt đồng bằng sông Cửu Long, và từ đó, những nhân

vật theo

sau, tất cả, [trừ một, Granger], là từ tiềm thức bật ra."

Ways of Escape.

Granger, một ký giả Mẽo, tên thực ngoài đời, Larry

Allen, đã từng được

Pulitzer khi tường thuật Đệ Nhị Chiến, chín năm trước đó. Greene gặp

anh ta năm

1951. Khi đó 43 tuổi, hào quang đã ở đằng sau, nhậu như hũ chìm. Khi,

một tay

nâng bi anh ta về bài viết, [Tên nó là gì nhỉ, Đường về Địa ngục,

đáng

Pulitzer quá đi chứ... ], Allen vặc lại: "Bộ anh nghĩ, tôi có ở đó hả?

Stephen Crane đã từng miêu tả một cuộc chiến mà ông không có mặt, tại

sao tôi

không thể? Vả chăng, chỉ là một cuộc chiến thuộc địa nhơ bẩn. Cho ly

nữa đi. Rồi

tụi mình đi kiếm gái."

Trong

Tẩu Vi

Thượng Sách. Greene có kể về mối tình của ông đối với Miền Nam Việt Nam,

và từ đó, đưa đến chuyện ông viết Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng…

Tin Văn post lại ở đây, như là một dữ kiện, cho thấy, Mẽo thực sự không

có ý

‘giầy xéo’ Miền Nam.

Và cái cú đầu độc tù Phú Lợi, hẳn là ‘diệu kế’ của đám VC nằm vùng.

Cái chuyện MB phải thống nhất đất nước, là đúng theo qui luật lịch sử

xứ Mít,

nhưng, do dùng phương pháp bá đạo mà hậu quả khủng khiếp 'nhãn tiền’

như ngày

nay!

Ui chao, lại nhớ cái đoạn trong Tam Quốc, khi Lưu Bị thỉnh thị quân sư

Khổng

Minh, làm cách nào lấy được xứ... Nam Kỳ, Khổng Minh bèn phán, có ba

cách,

vương đạo, trung đạo, và bá đạo [Gấu nhớ đại khái].

Sau khi nghe trình bầy, Lê Duẩn than, vương đạo khó quá, bụng mình đầy

cứt, làm

sao nói chuyện vương đạo, thôi, bá đạo đi!

Cú Phú Lợi đúng là như thế! Và cái giá của mấy anh tù VC Phú Lợi, giả

như có,

là cả cuộc chiến khốn kiếp!

*

Ways of escape: Tam thập lục kế, tẩu

vi thượng sách!

Hồi ký của Greene. Những đoạn viết về

Việt Nam

thật tuyệt.

Trở lại Anh, Greene nhớ Việt Nam

quá và đã mang theo cùng với ông một cái tẩu hít tô phe, như là một kỷ

niệm

tình cảm: cái tẩu mà ông đã hít lần chót, tại một tiệm hít ngoài đường

Catinat. Tay

chủ, người Tầu hợp với ông, và ông đã đi vài đường dậy tay này vài câu

tiếng

Anh. Tới ngày rời Việt Nam,

tay chủ tiệm hít bèn giúi vào tay Greene cái tẩu. Cây gậy thiêng nằm

trên một cái

dĩa tại căn phòng của Greene, ở Albany,

bị sứt mẻ tí tí, do di chuyển, đúng là một thần vật cổ, của những ngày

hạnh

phúc.

Lần thăm Việt Nam cuối, chàng [Greene] hít nhiều hơn lệ thường: thường,

nghĩa

là ba hoặc bốn bi, nhưng chỉ riêng trong lần cuối này, ở Sài Gòn, trong

khi chờ

đợi một tờ visa khác, tiếu lâm thay, của Vi Xi, chàng "thuốc" chàng

đến bất tri bất giác, he smoked himself inerte.

Trong những lần trước, thường xuyên là với những viên chức Tây, chàng

hít không

quá hai lần trong một tuần. Lần này, một tuần hít ba lần, mỗi lần trên

mười bi.

Ngay cả hít nhiều như thế cũng chẳng đủ biến chàng thành ghiền. Ghiền,

là phải hít

trên trăm bi một ngày.

Norman Sherry: Tiểu sử Greene

*

Trong Ba Mươi Sáu Chước, Tẩu Vi Thượng Sách, Ways

of escape, một dạng

hồi nhớ văn học, Greene cho biết, đúng là một cơ may, chuyện ông chết

mê chết

mệt xứ Đông Dương. Lần thứ nhất viếng thăm, ông chẳng hề nghĩ, mình sẽ

đẻ ra

được một cuốn tiểu thuyết thật bảnh, nhờ nó. Một người bạn cũ của ông,

từ hồi

chiến tranh, lúc đó là Lãnh sự tại Hà Nội, nơi một cuộc chiến

tranh khác

đang tiến diễn và hầu như hoàn toàn bị bỏ quên bởi báo chí Anh. Do đó,

sau Malaya,

ông bèn nháng qua Việt Nam

thăm bạn, chẳng hề nghĩ, vài năm sau, sẽ trải qua tất cả những mùa đông

của ông

ở đây.

"Tôi nhận thấy, Malaya

'đần' như một người đàn bà đẹp đôi khi 'độn'. Người ở đó thường nói,

'Bạn phải

thăm xứ xở này vào thời bình', và tôi thật tình muốn vặc lại, 'Nhưng tớ

chỉ

quan tâm tới cái xứ sở đần độn này, khi có máu'. Không có máu, nó trơ

ra với

vài câu lạc bộ Anh, với một dúm xì căng đan nho nhỏ, nằm tênh hênh chờ

một tay

Maugham nào đó mần báo cáo về chúng."

"Nhưng Đông Dương, khác hẳn. Ở đó, tôi nuốt trọn bùa yêu, ngải lú, tôi

cụng ly rượu tình với mấy đám sĩ quan Lực Lượng Lê Dương, mắt tay nào

cũng sáng

lên, khi vừa nghe nhắc đến hai tiếng Sài Gòn, hay Hà Nội."

Và bùa yêu ép phê liền tù tì, tôi muốn nói, giáng cú sét đánh đầu tiên

của nó,

qua những cô gái mảnh khảnh, thanh lịch, trong những chiếc quần lụa

trắng, qua

cái dáng chiều mầu thiếc xà xuống cánh đồng lúa trải dài ra mãi, đây đó

là mấy

chú trâu nước nặng nề trong cái dáng đi lảo đảo hai bên mông vốn có tự

thời

nguyên thuỷ của loài vật này, hay là qua mấy tiệm bán nước thơm của

người Tây ở

đường Catinat, hay trong những sòng bài của người Tầu ở Chợ Lớn,

nhưng trên

hết, là qua cái cảm giác bi bi hài hài, trớ trêu làm sao, và cũng

rất ư

là phấn chấn hồ hởi mà một dấu báo của hiểm nguy mang đến cho du khách

với cái

vé khứ hồi thủ sẵn ở trong túi: những tiệm ăn bao quanh bằng những hàng

dây kẽm

gai nhằm chống lại lựu đạn, những vọng gác cao lênh khênh dọc theo

những con lộ

nơi đồng bằng Nam Bộ với những lời cảnh báo thật là kỳ kỳ [bằng tiếng

Tây, lẽ

dĩ nhiên]: "Nếu bạn bị tấn công, và bị bắt giữ trên đường đi, hãy báo

liền

lập tức cho viên sếp đồn quan trọng đầu tiên".

Dịp đó, tôi ở hai tuần, và tranh thủ tối đa, tới giây phút cuối cùng,

cái giây

phút không thể tha thứ , "the unforgiving minute". Hà Nội cách Sài

Gòn bằng London xa Rome,

nhưng ngoài chuyện ăn ngủ... ở cả hai thành phố, tôi còn ban cho mình

những

chuyến tham quan nơi đồng bằng Nam Bộ, tới những giáo phái lạ lùng như

Cao Đài

mà những ông thánh của nó bao gồm Victor Hugo, Christ, Phật, và Tôn Dật

Tiên.

Ways of escape

Liệu giấc mơ về một cuộc cách mạng, thỏa mãn giấc mơ

như lòng chúng ta thèm

khát tương lai, của TTT, có gì liên can tới ‘lực lượng thứ ba’, vốn là

một giấc

mơ lớn, của Mẽo, nằm trong hành trang của Pyle, [Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng

],

khi tới Việt Nam.

Giấc mơ lớn của Mẽo, từ đó, cái mầm của Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng bật

ra,

khi Greene, trên đường trở về Sài Gòn, sau khi qua một đêm với tướng

Leroy, Hùm

Xám Bến Tre, như ông viết, trong Tam thập lục kế tẩu vi thượng

sách, Ways of

Escape.

"Cách đây chưa đầy một năm, [Geeene viết năm 1952], tôi đã từng tháp

tùng

Le Roy, tham quan vương quốc sông rạch, trên chiến thuyền của ông ta.

Lần này,

thay vì chiến thuyền, thì là du thuyền, thay vì dàn súng máy ở hai bên

mạn

thuyền, thì là chiếc máy chạy dĩa nhạc, và những vũ nữ.

Bản nhạc đang chơi, là từ phim Người Thứ Ba, như để vinh danh

tôi.

Tôi dùng chung phòng ngủ với một tay Mẽo, tùy viên kinh tế, chắc là

CIA, [an

American attached to an economic aid mission - the members were assumed

by the

French, probably correctly, to belong to the CIA]. Không giống

Pyle,

thông minh hơn, và ít ngu hơn [of less innocence]. Anh ta bốc phét,

suốt trên

đường từ Bến Tre về Sài Gòn, về sự cần thiết phải tìm cho ra một lực

lượng thứ

ba ở Việt Nam.

Cho tới lúc đó, tôi chưa giờ cận kề với giấc mộng lớn của Mẽo,

về những áp

phe ma quỉ, tại Đông phương, như là nó đã từng, tại Phi Châu.

Trong Người Mỹ Trầm Lặng, Pyle nhắc tới câu của tay ký giả York

Harding

– cái mà phía Đông cần, là một Lực Lượng Thứ Ba – anh ta xem có vẻ ngây

thơ,

nhưng thực sự đây chính là chính sách của Mẽo. Người Mẽo tìm kiếm một

nhà lãnh

đạo Việt Nam không tham nhũng, hoàn toàn quốc gia, an incorruptible,

purely nationalist

Vietnamese leader, người có thể kết hợp, unite, nhân dân Việt Nam, và

tạo thành

một thế đứng, một giải pháp, đối với Việt Minh CS.

Greene rất chắc chắn, về nguồn của Người Mỹ trầm lặng:

"Như vậy, đề tài NMTL tới với tôi, trong cuộc nói chuyện trên, về 'lực

lượng thứ ba', trên đường vượt đồng bằng sông Cửu Long, và từ đó, những

nhân

vật theo sau, tất cả, [trừ một, Granger], là từ tiềm thức bật ra."

Ways of Escape.

Granger, một ký giả Mẽo, tên thực ngoài đời, Larry Allen, đã từng được

Pulitzer

khi tường thuật Đệ Nhị Chiến, chín năm trước đó. Greene gặp anh ta năm

1951.

Khi đó 43 tuổi, hào quang đã ở đằng sau, nhậu như hũ chìm. Khi, một tay

nâng bi

anh ta về bài viết, [Tên nó là gì nhỉ, Đường về Địa ngục, đáng

Pulitzer

quá đi chứ... ], Allen vặc lại: "Bộ anh nghĩ, tôi có ở đó hả? Stephen

Crane đã từng miêu tả một cuộc chiến mà ông không có mặt, tại sao tôi

không thể?

Vả chăng, chỉ là một cuộc chiến thuộc địa nhơ bẩn. Cho ly nữa đi. Rồi

tụi mình

đi kiếm gái."

*

I

shared a room that night

with an American attached to an economic aid mission - the members were

assumed

by the French, probably correctly, to belong to the CIA. My companion

bore no

resemblance at all to Pyle, the quiet American of my story - he was a

man of

greater intelligence and of less innocence, but he lectured me all the

long

drive back to Saigon on the necessity of finding a 'third force in

Vietnam'. I

had never before come so close to the great American dream which was to

bedevil

affairs in the East as it was to do in Algeria. The only leader

discernible for the 'third force' was the self· styled General The. At

the time

of my first visit to the Caodaists he had been a colonel in the army of

the

Caodaist Pope - a force of twenty thousand men which theoretically

fought on

the French side. They had their own munitions factory in the Holy See

at Tay

Ninh; they supplemented what small arms they could squeeze out of the

French

with mortars made from the exhaust pipes of old cars. An ingenious

people - it

was difficult not to suspect their type of ingenuity in the bicycle

bombs which

went off in Saigon the following

year. The

time-bombs were concealed in plastic containers made in the shape of

bicycle

pumps and the bicycles were left in the parks outside the ministries

and

propped against walls ... A bicycle arouses no attention in Saigon.

It is as much a bicycle city as Copenhagen.

Between my two visits General

The (he had promoted himself) had deserted from the Caodaist army with

a few

hundred men and was now installed on the Holy Mountain,

outside Tay Ninh. He had declared war on both the French and the

Communists.

When my novel was eventually noticed in the New Yorker the reviewer

condemned

me for accusing my 'best friends' (the Americans) of murder since I had

attributed to them the responsibility for the great explosion - far

worse than

the trivial bicycle bombs - in the main square of Saigon when many

people lost

their lives. But what are the facts, of which the reviewer needless to

say was

ignorant? The Life photographer at the moment of the explosion was so

well

placed that he was able to take an astonishing and horrifying

photograph which

showed the body of a trishaw driver still upright after his legs had

been blown

off. This photograph was reproduced in an American propaganda magazine

published in Manila

over the title 'The work of Ho Chi Minh', although General The had

promptly and

proudly claimed the bomb as his own. Who had supplied the material to a

bandit

who was fighting French, Caodaists and Communists? There was certainly

evidence

of contacts between the American services and General The. A jeep with

the

bodies of two American women was found by a French rubber planter on

the route

to the sacred mountain - presumably they had been killed by the Viet

Minh, but

what were they doing on the plantation? The bodies were promptly

collected by

the American Embassy, and nothing more was heard of the incident. Not a

word

appeared in the Press. An American consul was arrested late at night on

the bridge

to Dakow [DaKao ?], (where Pyle in my novel lost his life) carrying

plastic

bombs in his car. Again the incident was hushed up for diplomatic

reasons.

So the subject of The Quiet

American came to me, during that talk of a 'third force' on the road

through

the delta, and my characters quickly followed, all but one of them from

the

unconscious. The exception was Granger, the American newspaper

correspondent.

The press conference in Hanoi

where he figures was recorded almost word for word in my journal at the

time. Perhaps

there is more direct reportage in The Quiet American than in any other

novel I

have written. I had determined to employ again the experience I had

gained with The End of the Affair in

the use of the first person and the

time-shift, and my

choice of a journalist as the 'I' seemed to me to justify the use of

reportage.

The press conference is not the only example of direct reporting. I was

in the

dive-bomber (the pilot had broken an order of General de Lattre by

taking me)

which attacked the Viet Minh post and I was on the patrol of the

Foreign Legion

paras outside Phat Diem. I still retain the sharp image of the dead

child

couched in the ditch beside his dead mother. The very neatness of their

bullet

wounds made their death more disturbing than the indiscriminate

massacre in the

canals around.

I went back to Indo-China for

the fourth and last time in 1955 after the defeat of the French in the

north,

and with some difficulty I reached Hanoi

- a sad city, abandoned by the French where I drank the last bottle of

beer

left in the cafe which I used to frequent with Monsieur Dupont. I was

feeling

very ill and tired and depressed. I sympathized with the victors, but I

sympathized with the French too. The French classics were yet on view

in a

small secondhand bookshop which Monsieur Dupont had rifled a few years

back,

but a hundred years of French civilization had fled with the Catholic

peasants

to the south. The Metropole Hotel where I used to stay was in the hands

of the

International Commission. Viet Minh sentries stood outside the building

where

de Lattre had made his promise, 'I leave you my wife as a symbol that France

will

never, never ... '

Day after day passed while I

tried to bully my way into the presence of Ho Chi Minh. It was the

period of

the crachin and my spirits sank with

the thin day-long drizzle of warm rain. I told my contacts I could wait

no

longer - tomorrow I would return to what was left of French territory

in the

north.

I don't know why my blackmail

succeeded, but I was summoned suddenly to take tea with Ho Chi Minh,

and now I

felt too ill for the meeting. There was only one thing to be done. I

went back

to an old Chinese chemist's shop in the rue des Voiles which I had

visited the

year before. The owner, it was said, was 'the Happiest Man in the

World'. There

I was able to smoke a few pipes of opium while the mah-jong pieces

rattled like

gravel on a beach. I had a passionate desire for the impossible - a

bottle of

Eno's. A messenger was dispatched and before the pipes were finished I

received

the impossible. I had drunk the last bottle of beer in Hanoi. Was this

the last bottle of Eno's?

Anyway the Eno's and the pipes took away the sickness and the inertia

and gave

me the energy to meet Ho Chi Minh at tea.

Of those four winters which I

passed in Indo-China opium has left the happiest memory, and as it

played an

important part in the life of Fowler, my character in The Quiet

American, I add

a few memories from my journal concerning it, for I am reluctant to

leave

Indo-China for ever with only a novel to remember it by.

31

December 1953. Saigon

One of the interests of

far

places is 'the friend of friends': some quality has attracted somebody

you

know, will it also attract yourself? This evening such a one came to

see me, a

naval doctor. After a whisky in my room, I drove round Saigon

with him, on the back of his motorcycle, to a couple of opium fumeries.

The

first was a cheap one, on the first floor over a tiny school where

pupils were

prepared for 'le certificat et le brevet'. The proprietor was smoking

himself:

a malade imaginaire dehydrated by his sixty pipes a day. A young girl

asleep,

and a young boy. Opium should not be for the young, but as the Chinese

believe

for the middle-aged and the old. Pipes here cost 10 piastres each (say

2s.).

Then we went on to a more elegant establishment - Chez Pola. Here one

reserves the room and can bring

a companion. A

great Chinese umbrella over the big circular bed. A bookshelf full of

books

beside the bed - it was odd to find two of my own novels in a fumerie:

Le

Ministère de la Peur, and Rocher de Brighton. I wrote a dédicace in

each of them. Here the pipes cost 30

piastres.

My experience of opium

began

in October 1951 when I was in Haiphong

on the way to the Baie d' Along. A French official took me after dinner

to a

small apartment in a back street - I could smell the opium as I came up

the

stairs. It was like the first sight of a beautiful woman

Ways of escape

Cái

cú bom nổ

trên đường Catinat, mặc dù Mẽo nói, đây là tác phẩm của Bác Hồ,

nhưng theo Greene, TMT hãnh diện tự nhận là tác giả.

Cái cú Greene blackmail Bác Hồ mà chẳng thú sao?

Nhưng thú nhất, có lẽ là những xen G. đi hít tô phe, và có lần thấy

sách của mình ở tiệm hút, bèn lôi ra, viết lời đề tặng.

Ui chao, giá mà Gấu cũng có tí kỷ niệm này thì thật tuyệt. Tưởng tượng

không thôi, vô một tiệm ở Cây Da Xà, thấy Những Ngày Ở Sài Gòn, trên giá

sách, kế bên bàn đèn, là đã thấy sướng mê tơi rồi!

*

31 December 1953. Saigon

One of the interests of far places is 'the friend of friends': some

quality has

attracted somebody you know, will it also attract yourself? This

evening such a

one came to see me, a naval doctor. After a whisky in my room, I drove

round Saigon with him, on

the back of his motorcycle, to a couple of opium fumeries. The first

was a

cheap one, on the first floor over a tiny school where pupils were

prepared for

'le certificat et le brevet'. The proprietor was smoking himself: a

malade imaginaire

dehydrated by his sixty pipes a day. A young girl asleep, and a young

boy.

Opium should not be for the young, but as the Chinese believe for the

middle-aged and the old. Pipes here cost 10 piastres each (say 2s.).

Then we

went on to a more elegant establishment - Chez Pola. Here one

reserves

the room and can bring a companion. A great Chinese umbrella over the

big

circular bed. A bookshelf full of books beside the bed - it was odd to

find two

of my own novels in a fumerie: Le Ministère de la Peur, and Rocher

de Brighton. I wrote a dédicace in each of them. Here

the pipes cost 30

piastres.

My experience of opium began in October 1951 when I was in Haiphong on the way to

the Baie d' Along. A French official took me after dinner to a small

apartment in

a back street - I could smell the opium as I came up the stairs. It was

like

the first sight of a beautiful woman with

whom one realizes that a relationship is possible: somebody whose

memory will

not be dimmed by a night's sleep.

The madame decided that as I

was a debutant I must have only four pipes, and so I am grateful to her

that my

first experience was delightful and not spoiled by the nausea of

over-smoking.

The ambiance won my heart at once - the hard couch, the leather pillow

like a

brick these stand for a certain austerity, the athleticism of pleasure,

while

the small lamp glowing on the face of the pipe-maker, as he kneads his

little

ball of brown gum over the flame until it bubbles and alters shape like

a

dream, the dimmed lights, the little chaste cups of unsweetened green

tea,

these stand for the' luxe et volupte'.

Each pipe from the moment the

needle plunges the little ball home and the bowl is reversed over the

flame

lasts no more than a quarter of a minute - the true inhaler can draw a

whole

pipeful into his lungs in one long inhalation. After two pipes I felt a

certain

drowsiness, after four my mind felt alert and calm - unhappiness and

fear of

the future became like something dimly remembered which I had thought

important

once. I, who feel shy at exhibiting the grossness of my French, found

myself

reciting a poem of Baudelaire to my companion, that beautiful poem of

escape, Invitation au Voyage. When I got home

that night I experienced for the first time the white night of opium.

One lies

relaxed and wakeful, not wanting sleep. We dread wakefulness when our

thoughts

are disturbed, but in this state one is calm - it would be wrong even

to say

that one is happy - happiness disturbs the pulse. And then suddenly

without

warning one sleeps. Never has one slept so deeply a whole night-long

sleep, and

then the waking and the luminous dial of the clock showing that twenty

minutes

of so-called real time have gone by. Again the calm lying awake, again

the deep

brief all-night sleep. Once in Saigon after smoking I went to bed at

1.30 and

had to rise again at 4.00 to catch a bomber to Hanoi, but in those less three hours

I slept

all tiredness away.

Not that night, but many

nights later, I had a curiously vivid dream. One does not dream as a

rule after

smoking, though sometimes one wakes with panic terror; one dreams, they

say,

during disintoxication, like de Quincey, when the mind and the body are

at war.

I dreamed that in some intellectual discussion I made the remark, 'It

would

have been interesting if at the birth of Our Lord there had been

present

someone who saw nothing at all,' and then, in the way that dreams have,

I was

that man. The shepherds were kneeling in prayer, the Wise Men were

offering

their gifts (I can still see in memory the shoulder and red-brown robe

of one

of them - the Ethiopian), but they were praying to, offering gifts to,

nothing

- a blank wall. I was puzzled and disturbed. I thought, 'If they are

offering

to nothing, they know what they are about, so I will offer to nothing

too,' and

putting my hand in my pocket I found a gold piece with which I had

intended to

buy myself a woman in Bethlehem. Years later I was reading one of the

gospels

and recognized the scene at which I had been an onlooker . “So they

were

offering their gifts to the mother of God,” I thought. 'Well, I brought

that

gold piece to Bethlehem

to give to a woman, and it seems I gave it to a woman after all.'

10 January 1954. Hanoi

With French friends to the

Chinese quarter of Hanoi.

We called first for our Chinese friend living over his warehouse of

dried

medicines from Hong Kong - bales and

bales and

bales of brittle quackery. The family were all gathered in one upper

room with

the dog and the cat - husband and wife, daughters, grandparents,

cousins. After

a cup of tea we paid a visit to a relative - variously known as Serpent

Head

and the Happiest Man in the World. All these Chinese houses have little

frontage, but run back a long way from the street. The Happiest Man in

the

World sat there between the narrow walls like a tunnel, in thin pajamas

- he

never troubled to dress. He was rich and he had inherited the business

from his

father before it was necessary for him to work and when his sons were

already

old enough to do the work for him. He was like a piece of dried

medicine

himself, skeletonized by opium. In the background the mah-jong players

built

their walls, demolished, reshuffled. They didn't even have to look at

the

pieces they drew, they could tell the design by a touch of the finger.

The game

made a noise like a stormy tide turning the shingle on a beach. I

smoked two

pipes as an aperitif, and after dinner at the New Pagoda returned and

smoked

five more.

11 January 1954. Hanoi

Dinner with French friends

and afterwards smoked six pipes. Gunfire and the heavy sound of

helicopters low

over the roofs bringing the wounded from - somewhere. The nearer you

are to

war, the less you know what is happening. The daily paper in Hanoi

prints less than the daily paper in Saigon, and that prints less than

the

papers in Paris.

The noise of the helicopters had an odd effect on opium smoking. It

drowned the

soft bubble of the wax over the flame, and because the pipe was silent,

the

opium seemed to lose a great deal of its perfume, in the way that a

cigarette

loses taste in the open air.

12 January 1954. Vientiane

Up early to catch a military

plane to Vientiane, the administrative

capital

of Laos.

The plane was a freighter with no seats. I sat on a packing case and

was glad

to arrive.

After lunch I made a rapid

tour of Vientiane.

Apart from one pagoda and the long sands of the Mekong

river, it is an uninteresting town consisting only of two real streets,

one

European restaurant, a club, the usual grubby market where apart from

food

there is only the debris of civilization - withered tubes of

toothpaste,

shop-soiled soaps, pots and pans from the Bon Marche. Fishes were small

and

expensive and covered with flies. There were little packets of dyed

sweets and

sickly cakes made out of rice colored mauve and pink. The fortune-maker

of Vientiane

was a man with

a small site let out as a bicycle park - hundreds of bicycles at 2

piastres a

time (say 20 centimes). When he had paid for his concession he was

likely to

make 600 piastres a day profit (say 6,000 francs). But in Eastern

countries

there are always wheels within wheels, and it was probable that the

concessionaire was only the ghost for one of the princes.

Sometimes one wonders why one

bothers to travel, to come eight thousand miles to find only Vientiane

at the

end of the road, and yet there is a curious satisfaction later, when

one reads

in England the war communiqués and the familiar names start from the

page - Nam

Dinh, Vientiane, Luang Prabang -looking so important temporarily on a

newspaper

page as though part of history, to remember them in terms of mauve rice

cakes,

the rat crossing the restaurant floor as it did tonight until it was

chased

away behind the bar. Places in history, one learns, are not so

important.

After dinner to the house of

Mr. X, a Eurasian and a habitual smoker. Thinned by his pipes, with

bony wrists

and ankles and the arms of a small boy, Mr. X was a charming and

melancholy

companion. He spoke beautifully clear French, peering down at his

needle

through steel-rimmed spectacles. His house was a hovel too small for

him to

find room for his wife and child whom he had left in Phnom Penh.

There was nothing to do in the

evening - the cinema showed only the oldest films, and there was really

nothing

to do all day either, but wait outside the government office where he

was

employed on small errands. A palm tree was his bookcase and he would

slip his

book or his newspaper into the crevices of the trunk when summoned into

the

house. Once I needed some wrapping paper and he went to the palm tree

to see

whether he had any saved. His opium was excellent, pure Laos

opium, and

he prepared the pipes admirably. Soon his French employers would be

packing up

in Laos, he would

go to France,

he

would have no more opium - all the ease of life would vanish but he was

incapable of considering the future. His sad amused Asiatic face peered

down at

the pipe while his bony fingers kneaded and warmed the brown seed of

contentment, and he spoke musically and precisely like a don on the

types and

years of opium - the opium of Laos,

Yunan, Szechuan, Istanbul, Benares -

ah, Benares, that was a kind to

remember over the years. *

13 January 1954

On again to Luang Prabang.

Where Vientiane

has two streets Luang Prabang has one, some shops, a tiny modest royal

palace

(the King is as poor as the state) and opposite the palace a steep hill

crowned

by a pagoda which contains - so it is believed - the giant footprint of

Buddha.

Little side streets run down to the Mekong,

here full of water. There is a sense of trees, temples, small quiet

homes, river

and peace. One can see the whole town in half an hour's walk, and one

could

live here, one feels, for weeks, working, walking, sleeping, if the

Viet Minh

were not on their way down from the mountains. We determined, tomorrow

before

returning, to take a boat up the Mekong

to the

grotto and the statue of Buddha which protects Luang Prabang from her

enemies.

There is more atmosphere of prayer in a pagoda than in most churches.

The

features of Buddha cannot be sentimentalized like the features of

Christ, there

are no hideous pictures on the wall, no stations of the Cross, no

straining

after unfelt agonies. I found myself praying to Buddha as always when I

enter a

pagoda, for now surely he is among our saints and his intercession will

be as

powerful as the Little Flower's - perhaps more powerful here among a

race akin

to his own.

After dinner I was very

tired, but five pipes of inferior opium - bitter with dross - smoked in

a

chauffeur's house made me feel fresh again. It was a house on piles and

at the

end of the long narrow veranda, screened from the dark and the

mosquitoes, a

small son knelt at a table doing his lessons while his mother squatted

beside

him. The soft recitation of his lesson accompanied the murmur and the

bubble of

the pipe.

16 January 1954. Saigon .

Laos remained careless Laos

till the end. f was worried by

the late arrival of the car and only just caught the plane which left

the

airfield at 7.00 in the dark. Two stops on the way to Saigon.

I got in about 12.30. Why is it that Saigon

is always so good to come back to? I remember on

my first journey to Africa, when I walked across Liberia,

I used to dream of the

delights of a hot bath, a good meal, a comfortable bed. I wanted to go

straight

from the African hut with the rats

* A connoisseur would say

'The number 1 Xieng Khouang opium of Laos' when referring to the

best

opium from this country. (As, for instance, rubber from Malaya

is described as Number1R.S.S.) Xieng Khouang is a province to the

north-east of Vientiane

where

the best opium is grown.

running down

the wall at

night to some luxury hotel in Europe

and enjoy

the contrast. In fact one never satisfactorily found the contrast -

either in Liberia

or later in Mexico.

Civilization was always

broken to one slowly: the trader's establishment at Grand Bassa was a

great

deal better than the jungle, the Consulate at Monrovia

was better than the tradesman's house, the cargo boat was an approach

to

civilization, by the time one reached England the contrast had

been

completely lost. Here in Indo-China one does capture the contrast: Vientiane is a century away from Saigon.

18 January 1954

After drinking with M and D

of the Sureté and a dinner with a number of people from the Legation, I

returned early to the hotel in order to meet a police commissioner

(half-caste)

and two Vietnamese plainclothes men who were going to take me on a tour

of Saigon's night side. Our first

fumerie was in the paillote district - a district of

thatched houses in a bad state of repair. In a small yard off the main

street

one found a complete village life - there was a cafe, a restaurant, a

brothel,

a fumerie. We climbed up a wooden ladder to an attic immediately under

the

thatch. The sloping roof was too low to stand upright, so that one

could only

crawl from the ladder on to one of the two big double mattresses spread

on the

floor covered with a clean white sheet. A cook was fetched and a girl,

an

attractive, dirty, slightly squint-eyed girl, who had obviously been

summoned

for my private pleasure. The police commissioner said, 'There is a

saying that

a pipe prepared by a woman is more sweet.' In fact the girl only went

through

the motions of warming the opium bead for a moment before handing it

over to

the expert cook. Not knowing how many fumeries the night would produce

I smoked

only two pipes, and after the first pipe the Vietnamese police

scrambled

discreetly down the ladder so that I could make use of the double bed.

This I

had no wish to do. If there had been no other reason it would still

have been

difficult to concentrate on pleasure, with the three Vietnamese police

officers

at the bottom of the ladder, a few feet away, listening and drinking

cups of

tea. My only word of Vietnamese was 'No,' and the girl's only word of

English

was 'OK,' and it became a polite struggle between the two phrases.

At the bottom of the ladder I

had a cup of tea with the police officers and the very beautiful madame

who had

the calm face of a young nun. I tried to explain to the Vietnamese

commissioner

that my interest tonight was in ambiance only. This dampened the

spirits of the

party.

I asked them whether they

could show me a more elegant brothel and they drove at once towards the

outskirts of the city. It was now about one o'clock in the morning. We

stopped

by a small wayside café and entered. Immediately inside the door there

was a

large bed with a tumble of girls on it and one man emerging from the

flurry. I

caught sight of a face, a sleeve, a foot. We went through to the cafe

and drank

orangeade. The madame reminded me of the old Javanese bawd in South

Pacific.

When we left the man on the bed had gone and a couple of Americans sat

among

the girls, waiting for their pipes. One was bearded and gold-spectacled

and

looked like a professor and the other was wearing shorts. The night was

very

mosquitoes and he must have been bitten almost beyond endurance.

Perhaps this

made his temper short. He seemed to think we had come in to close the

place and

resented me.

After the loud angry voices

of the Americans, the bearded face and the fat knees, it was a change

to enter

a Chinese fumerie in Cholon. Here in this place of bare wooden shelves

were

quiet and courtesy. The price of pipes - one price for small pipes and

one

price for large pipes - hung on the wall. I had never seen this before

in a

fumerie. I smoked two pipes only and the Chinese proprietor refused to

allow me

to pay. He said I was the first European to smoke there and that he

would not

take my money. It was 2.30 and I went home to bed. I had disappointed

my

Vietnamese companions. In the night I woke dispirited by the faults of

the play

I was writing, The Potting Shed, and

tried unsuccessfully to revise it in my mind.

20 January 1954. Phnom Penh

After dinner my host and I

drove to the centre of Phnom

Penh

and parked the car. I signaled to a rickshaw driver, putting my thumb

in my

mouth and making a gesture rather like a long nose. This is always

understood

to mean that one wants to smoke. He led us to a rather dreary yard off

the rue

A -. There were a lot of dustbins, a rat moved among them, and a few

people lay

under shabby mosquito-nets. Upstairs on the first floor, off a balcony,

was the

fumerie. It was fairly full and the trousers were hanging like banners

in a

cathedral nave. I had eight pipes and a distinguished looking man in

underpants

helped to translate my wishes. He was apparently a teacher of English.

9 February 1954. Saigon

After dinner at the

Arc-en-Ciel, to the fumerie opposite the Casino above the school. I had

only

five pipes, but that night was very dopey. First I had a nightmare,

then I was

haunted by squares - architectural squares which reminded me of Angkor,

equal

distances, etc., and then mathematical squares - people's income, etc.,

square

after square after square which seemed to go on all night. At last I

woke and

when I slept again I had a strange complete dream such as I have

experienced

only after opium. I was coming down the steps of a club in St James's Street

and on the steps I met

the Devil who was wearing a tweed motoring coat and a deerstalker cap.

He had

long black Edwardian moustaches. In the street a girl, with whom I was

apparently living, was waiting for me in a car. The Devil stopped me

and asked

whether I would like to have a year to live again or to skip a year and

see

what would be happening to me two years from now. I told him I had no

wish to

live over any year again and I would like to have a glimpse of two

years ahead.

Immediately the Devil vanished and I was holding in my hands a letter.

I opened

the letter - it was from some girl whom I knew only slightly. It was a

very

tender letter, and a letter of farewell. Obviously during that missing

year we

had reached a relationship which she was now ending. Looking down at

the woman

in the car I thought, ‘I must not show her the letter, for how absurd

it would

be if she were to be jealous of a girl whom I don't yet know.' I went

into my

room (I was no longer in the club) and tore the letter into small

pieces, but

at the bottom of the envelope were some beads which must have had a

sentimental

significance. I was unwilling to destroy these and opening a drawer put

them in

and locked the drawer. As I did so it suddenly occurred to me, ‘In two

years'

time I shall be doing just this, opening a drawer, putting away the

beads, and

finding the beads are already in the drawer.' Then I woke.

There remains another memory

which I find it difficult to dispel, the doom-laden twenty-fours I

spent in Dien Bien Phu in January

1954. Nine years later when I

was asked by the Sunday Times to

write on ‘a decisive battle of my choice', it was Dien

Bien Phu that came straightway to my mind.

Fifteen Decisive

Battles of the World - Sir

Edward

Creasy gave that classic title to his

book in 1851, but it is doubtful whether any battle listed there was

more

decisive than Dien Bien Phu in 1954.

Even

Sedan, which came too late for Creasy, was only an episode in

Franco-German

relations, decisive for the moment in a provincial dispute, but the

decision

was to be reversed in 1918, and that decision again in 1940.

Dien

Bien Phu, however,

was a

defeat for more than the French army. The battle marked virtually the

end of

any hope the Western Powers might have entertained that they could

dominate the

East. The French with Cartesian clarity accepted the verdict. So, too,

to a

lesser extent, did the British: the independence of Malaya, whether the

Malays

like to think it or not, was won for them when the Communist forces of

General

Giap, an ex-geography professor of Hanoi University, defeated the

forces of

General Navarre, ex-cavalry officer, ex-Deuxieme Bureau chief, at Dien

Bien

Phu. (That young Americans were still to die in Vietnam

only shows that it takes

time for the echoes even of a total defeat to encircle the globe.)

The battle

itself, the heroic

stand of Colonel de Castries' men while the conference of the Powers at

Geneva

dragged along, through the debates on Korea, towards the second item on

the

agenda - Indo-China - every speech in Switzerland punctuated by deaths

in that

valley in Tonkin - has been described many times. Courage will always

find a

chronicler, but what remains a mystery to this day is why the battle

was ever

fought at all, why twelve battalions of the French army were committed

to the

defence of an armed camp situated in a hopeless geographical

terrain-hopeless

for defence and hopeless for the second objective, since the camp was

intended