|

|

|

Trong cuốn của

Robert Hass, Gấu mới dinh về, có bài "Cơn giận dữ của Chekhov", Chekhov's anger, thật là

tuyệt, và lại có tí tính thời sự, vì liên quan đến truyện ngắn, và

truyện ngắn mới

được Nobel.

Gấu chép lại ở đây, mấy câu thật thú, đọc khi ở tiệm sách, và vì thế

mà dinh về dinh [đưa nàng về dinh!]:

Chúng ta được

dạy từ những người viết giả tưởng của thế kỷ 19, là đọc tác phẩm, vì

cái nhìn của

nó, không chỉ về những cuộc đời riêng tư, mà về trọn xã hội.

We have been

taught by the fiction writers of the nineteenth century to read work

for its

view not just of individual lives but of a whole society.

Chekho tính làm cú này,

không phải viết rộng và mang tính biểu tượng, largely and symbolically,

nhưng choàng lên một khối lượng khổng lồ những cuộc đời Nga, but by

covering

immense amounts of Russian life.

Cẩm như Trò

Đời, Comédie humaine, của Balzac, của Tẩy.

Nhưng câu kết

bài viết mới cực thú:

Nếu Chekhov không

phải là một trong những nhà tiểu thuyết gia vĩ đại nhất, thì ông là 1

trong những

nhà thi sĩ lớn lao nhất.

Robert

Hass,

1986.

Robert Hass

MARCH I [1998]

Marie Howe

Marie Howe's

new book, her second book of poems, is called What the Living Do (Norton). Many

of the poems deal with a beloved brother's death from AIDS, but the

book begins

with poems of childhood and adolescence. The boys' fort that the girls

couldn't

go into. The initiation where boys tie up girls, and things start to

get out of

hand, and the one boy the girls might trust is afraid to say, "Stop

it." The pajama parties where girls talk about boys and practice

kissing.

They're delicious poems, and they

have the effect of making you understand how powerful the love between

a

brother and sister can be, and what it might mean to have your older

brother and protector die before your eyes.

Howe's way

with language is very spare. Many of the poems have a stripped-down,

point-blank quality that gives them a certain radiance.

Here's one:

The Last Time

The last

time we had dinner together in a restaurant

with white

tablecloths, he leaned forward

and took my

two hands in his hands and said,

I'm going to

die soon. I want you to know that.

And I said,

I think I do know.

And he said,

What surprises me is that you don't.

And I said,

I do. And he said, What?

And I said,

Know that you're going to die.

And he said,

No, I mean know that you are.

Ui chao GCC đọc

bài thơ này, thì lại nhớ đến Sad Seagull, và cái lần ngồi với em, buổi

sáng, tại

1 quán Starbucks ở Little Saigon, và có thể, “anh đang chết, ở khu

Phước Lộc Thọ”, là đã

được tiên tri từ những dòng thơ trên.

Tks. NQT

NOVEMBER 21 [1999]

Thanksgiving:

Daniel Halpern

Anyone who

has had a newborn arrive in their life knows how powerful and hard to

describe

the emotions are. Twentieth-century poets have mostly stayed away from

them.

They are too frail. They are not mammal grief and rage, even though

they can

turn into grief and rage. (That's what King Lear is about.) And the

example of

the tradition of domestic and familial poetry in Victorian America has

not

encouraged us. It made the subject seem impossible to approach without

sentimentality. Language makes the distinction: we speak of anger and

desire as

"feeling," the tender and uneasy stuff around the helplessness of

infants, and the impulse to protect children we call "sentiment." And

it's probably well that we do. Because they are frail emotions, and

they are

capable of turning into something quite savage. Nevertheless it is a

deep

thing, the wonder (and fear) at the arrival of a newborn child, and the

process

of-hard to know how else to say it-falling in love that parents go

through with

this creature given into their care. How do you talk about it?

Daniel Halpern, in his new book Something Shining (Knopf),

takes the subject on. He's my editor, and an old friend, and a poet

I've been

reading for twenty years or more. I've always thought of him as a poet

on the model

of the Roman poet Horace, with a poised and immensely civilized mind

for the

life we live, its large and small panics and decorums, and a civilized

balance

in his verse, in which orderliness can sometimes seem sinister and wry,

and

sometimes seem a gift, the kind of gift social being can give to one

another,

like a well-set table. Reading him has, over the years, made for very

good

company, this intelligence that is reasonably disenchanted, keeps an

eye on the

decades as they pass, the telling particulars in the social habits of a

generation, its ardors, suavities, and defeats.

And now this book that requires another kind of

poise. How do

you write about the whole business of becoming a parent, and about the

way this

attachment, this profound and life-defining tenderness and wonder,

grows in us.

He goes straight to it, and succeeds, I think. Have a look:

After the

Vigil

They turn

up, no longer nameless,

their bodies

clear, so nearly pure

they appear

in morning light transparent.

They turn up

and one day look at you

for the

first time, their eyes sure now

you are one

of theirs, surely here to stay.

They turn up

wearing an expression of yours,

imitating

your mouth, the smile perfected

over years

of enduring amusing moments.

They turn up

without a past, their fingers,

inexact

instruments that examine what carpets

their turf,

what they inherit through blood.

They turn up

with your future, if not in mind

very much in

the explosive story of their genes,

in gesture

foreshadowing the what's-to-come.

They turn up

with your hair-albeit not much

of

it-something in the color, the curl of it

after the

bath, its bearing after sleep.

They turn up

already on their own, ideas

of their

own, settling on their own limits,

their

particular sense of things.

They turn up

and we have been waiting,

as they have

without knowing. They turn

into this

world, keeping their own counsel.

NOVEMBER 21 [1999]

Thanksgiving:

Daniel Halpern

Anyone who

has had a newborn arrive in their life knows how powerful and hard to

describe

the emotions are. Twentieth-century poets have mostly stayed away from

them.

They are too frail. They are not mammal grief and rage, even though

they can

turn into grief and rage. (That's what King Lear is about.) And the

example of

the tradition of domestic and familial poetry in Victorian America has

not

encouraged us. It made the subject seem impossible to approach without

sentimentality. Language makes the distinction: we speak of anger and

desire as

"feeling," the tender and uneasy stuff around the helplessness of

infants, and the impulse to protect children we call "sentiment." And

it's probably well that we do. Because they are frail emotions, and

they are

capable of turning into something quite savage. Nevertheless it is a

deep

thing, the wonder (and fear) at the arrival of a newborn child, and the

process

of-hard to know how else to say it-falling in love that parents go

through with

this creature given into their care. How do you talk about it?

Daniel Halpern, in his new book Something Shining (Knopf),

takes the subject on. He's my editor, and an old friend, and a poet

I've been

reading for twenty years or more. I've always thought of him as a poet

on the model

of the Roman poet Horace, with a poised and immensely civilized mind

for the

life we live, its large and small panics and decorums, and a civilized

balance

in his verse, in which orderliness can sometimes seem sinister and wry,

and

sometimes seem a gift, the kind of gift social being can give to one

another,

like a well-set table. Reading him has, over the years, made for very

good

company, this intelligence that is reasonably disenchanted, keeps an

eye on the

decades as they pass, the telling particulars in the social habits of a

generation, its ardors, suavities, and defeats.

And now this book that requires another kind of

poise. How do

you write about the whole business of becoming a parent, and about the

way this

attachment, this profound and life-defining tenderness and wonder,

grows in us.

He goes straight to it, and succeeds, I think. Have a look:

After the

Vigil

They turn

up, no longer nameless,

their bodies

clear, so nearly pure

they appear

in morning light transparent.

They turn up

and one day look at you

for the

first time, their eyes sure now

you are one

of theirs, surely here to stay.

They turn up

wearing an expression of yours,

imitating

your mouth, the smile perfected

over years

of enduring amusing moments.

They turn up

without a past, their fingers,

inexact

instruments that examine what carpets

their turf,

what they inherit through blood.

They turn up

with your future, if not in mind

very much in

the explosive story of their genes,

in gesture

foreshadowing the what's-to-come.

They turn up

with your hair-albeit not much

of

it-something in the color, the curl of it

after the

bath, its bearing after sleep.

They turn up

already on their own, ideas

of their

own, settling on their own limits,

their

particular sense of things.

They turn up

and we have been waiting,

as they have

without knowing. They turn

into this

world, keeping their own counsel.

FEBRUARY I [1998]

Một

nhà thơ Ba Lan: Adam

Zagajewski

Một trong những thơ đương thời

mà tôi mê, là Adam Zagajewski, một

nhà thơ Ba Lan, sống ở Paris, thành viên của thế hệ "Solidarity". Hai

tập thơ, và hai tập tiểu luận của ông, là những tác phẩm [đầy tính]

tưởng

tượng, và ngạc nhiên, về chính trị, và nghệ thuật. Mới đây, ông có nửa

năm làm

thầy ở Houston. Và ở đây, 1 bài thơ, từ cuốn mới ra lò của ông, Chủ

nghĩa

thần bí cho những người mới bắt đầu, là từ kinh nghiệm này. Một bài

thơ về

1 cái đầu lừ khừ, vào cái giờ chạng vạng, khi ý thức lập loè như ánh

đèn của

viên phi công:

Houston, 6

P.M.

Âu Châu đã

ngủ rồi, ở bên dưới cái khăn choàng xộc xệch, thô kệch

Của những

biên giới,

Và những hận

thù cũ, xưa: Pháp làm ổ tới Đức,

Bosnia trong

vòng tay của Serbia.

Lobely

Sicily trong biển xanh da trời

Mới đầu buổi

chiều, ở đây, đèn đã thắp,

Và mặt trời

u tối nhạt nhòa dần.

Tôi một

mình. Đọc tí tí, nghĩ tí ti.

Nghe ti ti

tí âm nhạc.

Tôi ở nơi,

có tình bạn,

Nhưng không

có một người bạn, nơi say mê,

Nở rộ không

cần sự thần kỳ

Nơi người chết

cười ha hả.

Tôi một mình

là bởi vì Âu Châu đang ngủ.

Tình yêu của

tôi ngủ trong một căn nhà cao ở ngoại vi Paris.

Ở Krakow và ở

Paris bạn bè của tôi,

Lội qua cùng

con sông lú, lấp, quên lãng.

Tôi đọc và

nghĩ; trong một bài thơ tôi thấy câu này,

“Có những cú

đánh thật khủng khiếp… Đừng hỏi!”

Tôi đếch hỏi,

tất nhiên.

Một chiếc trực

thăng làm vỡ mẹ buổi chiều êm ả.

Ở đây không

có những loài chim “nightingales” hay “blackbirds”.

Với tiếng

hót buồn, ngọt của chúng

Và bắt chước

mọi tiếng người.

Thơ vời

chúng ta tới với cuộc sống, với sự can đảm

Đối diện cái

bóng lớn mãi ra.

Bạn có thể

đưa mắt nhìn một cách bình thản Trái Đất

Như một phi

hành gia tuyệt hảo?

Dưng không,

Từ biếng

nhác vô hại,

Từ Hy Lạp của

những cuốn sách

Từ Jerusalem

của hồi tưởng;

Bất thình

lình xuất hiện

Một hòn đảo

của một bài thơ, không có người ở;

Một tên

[thuyền trưởng] Cook mới

Sẽ có một

ngày, khám phá ra nó.

Âu Châu thì

đã ngủ rồi.

Những con

thú của ban đêm,

Ảm đạm, và

tham lam

Dọn vô, mở

cuộc giết

Chẳng mấy chốc

Mẽo cũng ngủ.

Người dịch là

Clare Cavanagh. Một bài thơ không đơn giản. Rắc rối, phải nói thế - lưu

vong, mất

mát, ở 1 nơi mà anh ta chẳng cảm thấy chân của mình dính vào đất, hay,

như một mầm hạt, loay hoay tìm cách trổ rễ; cảm quan sắc bén về bạo

động của lịch sử, cái lừ đừ của nhịp sống của chúng ta, như 1 đáp ứng

[tương quan], với bạo

lực đó, "chuyện thường ngày ở huyện" liên quan đến “ngũ khoái” của

chúng

ta (ăn ngủ, đi đứng…). Cảm quan của

Zagajewski về quyền năng nghệ thuật - của những cuốn sách, âm nhạc,

thơ ca –

thì chẳng hề tiếu lâm khôi hài, hay mỉa mai châm biếm. Trong tác phẩm

của ông, Trái

đất thuộc về cái bóng, thơ, về can đảm và ánh sáng. Nhưng trong bài thơ

này,

thơ là 1 hòn đảo, không người ở, chờ được khám phá, và trong khúc thơ

chót, những

con vật của đêm bèn tiến vô. Quả là 1 bài “Ru mãi ngàn năm" khá khủng

khiếp!

“Có những cú

khủng khiếp… Đừng hỏi”, là dòng thơ thứ nhất, dùng làm tựa đề cho bài

thơ, từ tập

thơ đầu tiên của nhà thơ lớn, người Peru, César

Vallejo, mất năm 1938, nhan đề “Los

Heraldos Negros”, “Những

thiên sứ đen”. Cuốn thơ và bài thơ đều rất đáng tìm đọc. Còn chi tiết

này: Có

loài chim hét, blackbird, ở Texas, nhưng không phải Turdus

merula, the European blackbird, một loài chim hét

Âu Châu,

hót rất hay.

Tiểu luận

và

thơ của Zagajewski thì thật đáng đọc. Cả hai thì đều sáng ngời, thông

minh một

cách sắc sảo, chất khôi hài ở trong đó thì được chắt ra từ cuộc gặp gỡ

của Đông

Âu với lịch sử, và cũng đầy niềm vui bất ngờ. “Chủ nghĩa thần bí dành

cho những

kẻ mới bắt đầu” có những phẩm chất đó, và, cũng còn có, một nỗi buồn

rầu liên lỉ,

như thể, khi lịch sử, qua một bước ngoặt đáng khuyến khích của nó, như

ở Ba

Lan, những cảnh sắc chán chường mà chúng ta cưu mang ở trong chúng ta,

và của

thế giới, tiếp tục “u u”, những âm vang, với bạo lực và nỗi khốn cùng,

ở đâu đó,

được làm mới, và trở nên sáng sủa hơn.

FEBRUARY I [1998]

A Polish Poet: Adam

Zagajewski

One of my favorite contemporary

poets is Adam Zagajewski, a Polish

poet who lives in Paris. Zagajewski was a member of the generation of

Polish writers who came of age during the Solidarity years. Two volumes

of

translations of his poems have been published in English, Tremor

and Canvas,

both from Farrar, Straus & Giroux, and two volumes of his essays, Solidarity,

Solitude (Ecco Press) and Two Cities (Farrar, Straus &

Giroux),

imaginative and surprising books about politics and art. Lately, he has

been

teaching half the year in Houston. And here, from his new book, Mysticism

for Beginners (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), is a poem that comes

out of

that experience. It's a poem of the idling mind in that hour of dusk

when

consciousness flickers like a pilot light:

Một trong những thơ đương thời

mà tôi mê, là Adam Zagajewski, một

nhà thơ Ba Lan, sống ở Paris, thành viên của thế hệ "Solidarity". Hai

tập thơ, và hai tập tiểu luận của ông, là những tác phẩm [đầy tính]

tưởng

tượng, và ngạc nhiên, về chính trị, và nghệ thuật. Mới đây, ông có nửa

năm làm

thầy ở Houston. Và ở đây, 1 bài thơ, từ cuốn mới ra lò của ông, Chủ

nghĩa

thần bí cho những người mới bắt đầu, là từ kinh nghiệm này. Một bài

thơ về

1 cái đầu lừ khừ, vào cái giờ chạng vạng, khi ý thức lập loè như ánh

đèn của

viên phi công:

Houston, 6

P.M.

Europe already sleeps beneath a

coarse plaid of borders

and ancient hatreds: France nestled

up to Germany, Bosnia in Serbia's arms,

Lobely Sicily in azure seas.

It's early evening here, the

lamp is lit

and the dark sun swiftly fades.

I'm alone. I read a little, think a little,

listen to a little music.

I'm where there's friendship,

but no friends, where enchantment

grows without magic,

where the dead laugh.

Tôi ở nơi có tình bạn,

Nhưng không có một người bạn, nơi sự thích say mê, thích thú

Nở rộ không cần sự thần kỳ

Nơi người chết cười.

I'm alone because Europe is

sleeping. My love

sleeps in a tall house on the outskirts of Paris.

In Krakow and Paris my friends

wade in the same river of oblivion.

I read and think; in one poem

I found the phrase "There are blows so terrible ...

Don't ask!" I don't. A helicopter

breaks the evening quiet.

Poetry calls us to a higher

life,

but what's low is just as eloquent,

more plangent than Indo-European,

stronger than my books and records.

There are no nightingales or

blackbirds here

with their sad, sweet cantilenas,

and mimics every living voice.

Poetry summons us to life, to

courage

in the face of the growing shadow.

Can you gaze calmly at the Earth

like the perfect astronaut?

Out of harmless indolence, the

Greece of books,

and the Jerusalem of memory there suddenly appears

the island of a poem, unpeopled;

some new Cook will discover it one day.

Europe is already sleeping.

Night's animals,

mournful and rapacious,

move in for the kill.

Soon America will be sleeping, too.

Houston, 6

P.M.

Âu Châu đã

ngủ rồi, ở bên dưới cái khăn choàng xộc xệch, thô kệch

Của những

biên giới,

Và những hận

thù cũ, xưa: Pháp làm ổ tới Đức,

Bosnia trong

vòng tay của Serbia.

Lobely

Sicily trong biển xanh da trời

Mới đầu buổi

chiều, ở đây, đèn đã thắp,

Và mặt trời

u tối nhạt nhòa dần.

Tôi một

mình. Đọc tí tí, nghĩ tí ti.

Nghe ti ti

tí âm nhạc.

Tôi ở nơi,

có tình bạn,

Nhưng không

có một người bạn, nơi say mê,

Nở rộ không

cần sự thần kỳ

Nơi người chết

cười ha hả.

Tôi một mình

là bởi vì Âu Châu đang ngủ.

Tình yêu của

tôi ngủ trong một căn nhà cao ở ngoại vi Paris.

Ở Krakow và ở

Paris bạn bè của tôi,

Lội qua cùng

con sông lú, lấp, quên lãng.

Tôi đọc và

nghĩ; trong một bài thơ tôi thấy câu này,

“Có những cú

đánh thật khủng khiếp… Đừng hỏi!”

Tôi đếch hỏi,

tất nhiên.

Một chiếc trực

thăng làm vỡ mẹ buổi chiều êm ả.

Ở đây không

có những loài chim “nightingales” hay “blackbirds”.

Với tiếng

hót buồn, ngọt của chúng

Và bắt chước

mọi tiếng người.

Thơ vời

chúng ta tới với cuộc sống, với sự can đảm

Đối diện cái

bóng lớn mãi ra.

Bạn có thể

đưa mắt nhìn một cách bình thản Trái Đất

Như một phi

hành gia tuyệt hảo?

Dưng không,

Từ biếng

nhác vô hại,

Từ Hy Lạp của

những cuốn sách

Từ Jerusalem

của hồi tưởng;

Bất thình

lình xuất hiện

Một hòn đảo

của một bài thơ, không có người ở;

Một tên

[thuyền trưởng] Cook mới

Sẽ có một

ngày, khám phá ra nó.

Âu Châu thì

đã ngủ rồi.

Những con

thú của ban đêm,

Ảm đạm, và

tham lam

Dọn vô, mở

cuộc giết

Chẳng mấy chốc

Mẽo cũng ngủ.

The

translator is Clare Cavanagh. It's a complicated poem-the exile at a

loss in a

place where he cannot feel roots, or rather like some seed beginning

tentatively to send out roots; the acute sense of the violence of

history, the

oddness of the circadian rhythms of our lives in relation to that

violence, the

ordinariness of sleeping and waking. Zagajewski's sense of the power of

art-of

books, music, poetry-is never ironic. In his work Earth belongs to the

shadow,

poetry to courage and the light. But in this poem, anyway, poetry is an

island,

unpeopled, waiting to be discovered, and in the last stanza the night

animals

are moving in. A rather terrible lullaby.

There are perhaps a couple of details to

gloss. The line "There are blows so terrible ... Don't ask" comes

from the great Peruvian poet César Vallejo who died in 1938. This comes

from

the first line of the title poem of his first book, Los Heraldos Negros

(The

Black Messengers). It is a book and a

poem very much worth looking up. And another detail: there are, of

course,

blackbirds in Texas, but not Turdus merula, the European blackbird,

which is a

species of thrush and has a very rich song.

Zagajewski's essays and poems are worth

getting to know. Both can be radiant, sharply intelligent, suffused

with an

irony bred of Eastern Europe’s encounter with history, but full also of

unexpected joy. Mysticism for Beginners has these qualities, also a

restless

melancholy, as if, when history takes an encouraging turn, as it has in

Poland,

the despairing landscapes that we carry inside us and that the world

keeps

echoing with renewed violence and misery elsewhere become more clear.

Người dịch là

Clare Cavanagh. Một bài thơ không đơn giản. Rắc rối, phải nói thế - lưu

vong, mất

mát, ở 1 nơi mà anh ta chẳng cảm thấy chân của mình dính vào đất, hay,

như một mầm hạt, loay hoay tìm cách trổ rễ; cảm quan sắc bén về bạo

động của lịch sử, cái sự

lừ đừ của nhịp sống của chúng ta, như 1 đáp ứng [tương quan], với bạo

lực đó, "chuyện thường này ở huyện" liên quan đến “ngũ khoái” của chúng

ta (ăn ngủ, đi đứng…). Cảm quan của

Zagajewski về quyền năng của nghệ thuật - của những cuốn sách, âm nhạc,

thơ ca –

thì chẳng hề tiếu lâm khôi hài, hay mỉa mai châm biếm. Trong tác phẩm

của ông, Trái

đất thuộc về cái bóng, thơ, về can đảm và ánh sáng. Nhưng trong bài thơ

này,

thơ là 1 hòn đảo, không người ở, chờ được khám phá, và trong khúc thơ

chót, những

con vật của đêm bèn tiến vô. Quả là 1 bài “Ru mãi ngàn năm" khá khủng

khiếp!

MAY 3 [1998]

In Memoriam:

Octavia Paz

I was in San

Miguel Allende in January when I heard that Octavio Paz was gravely

ill. My

hotel room had a rooftop patio. When I walked out onto it at dawn, six

thousand

feet up in the Sierra Madre, I looked out at a late Renaissance dome,

eighteenth-century church spires, laundry lines, utility lines, black

rooftop

cats gazing with what seemed religious reverence at the pigeons they

could not

quite reach, and in the distance at the lines of low bare hills that

formed the

high shallow valley of San Miguel. Overhead

there was a flock of what must have been two hundred cormorants flying

silently

and swiftly north. In the dawn light it looked as if the white sky were

full of

broken black crosses, a kind of aerial, fast-moving cemetery. It could

have

been an image from one of his poems.

He was not

only Mexico's greatest poet. He was one of the most remarkable literary

figures

of this half century. His essays are at least as compelling as his

poems and a

good way for English readers to get to know him. Paz's great prose book

is

probably his stunning meditation on the nature of poetry, The Bow and the Lyre, and there

are others: his book-length essay on

Mexico and Mexican culture, The

Labyrinth of Solitude,

and his biographical study of Mexico's great poet of the

Colonial Period, Sor Juana de la Cruz, and his essays on history and

politics, One Earth, Four or Five

Worlds, and his essays on Mexican art. Only Czeslaw

Milosz among the poets of his generation has had the same depth and

range.

But he was a

poet first of all. The best volumes of his work in English are Selected Poems

and A Tree Within, both

published by New Directions. Here is one

of his poems, gorgeous in Spanish, and you can almost hear the original

in this

translation from Selected Poems:

Tưởng niệm

Octavio Paz

Tôi ở San

Miguel Allende, vào tháng

Giêng, thì nghe tin ông bịnh nặng. Căn phòng khách sạn của tôi có cái

terrace.

Buổi sáng sớm, tôi ra terrace, từ trên đỉnh cồn nhìn xuống thành phố,

những vòm thời

kỳ Phục Hưng muộn, những đuờng xoắn nhà thờ thế kỷ 18, những đường giặt

ủi, tiện

ích, những con mèo đen trên mái nhà, với cái nhìn có vẻ kính cẩn, và

nhuốm tí mùi

tôn giáo, gửi tới những con bồ câu, chúng không làm sao sơ múi, vì

ngoài tầm nhảy, và

xa hơn tí nữa, là những đường viền của những ngọn đồi trần trụi, thấp,

tạo thành

cái dáng của thung lũng San Miguel. Trên đầu tôi, cả 1 đàn chim cốc,

chừng hai

trăm con, lặng lẽ, lầm lũi di chuyển về phương bắc. Trong ánh sáng lờ

mờ của buổi

sáng tinh sương, cả bầu trời màu trắng thì đầy những cây thập tự

đen, gãy, bể, chắng khác chi một nghĩa địa đang lặng lẽ, nhanh lẹ di

động. Hẳn

là hình ảnh này, là từ trong thơ của ông, được thiên nhiên lập lại.

Ông không chỉ là nhà thơ Mexico lớn lao nhất. Ông là

1 trong những

khuôn mặt văn học đáng kể nhất của nửa thế kỷ này. Những bài tiểu luận

của ông

thì cũng dữ dằn, hiếp đáp chúng ta, chẳng thua gì thơ của ông, và là 1

cách thật

tốt, cho độc giả tiếng Anh biết tới ông. Cuốn thơ xuôi lớn của ông có

lẽ là trầm

tư ngỡ ngàng về thơ, The Bow and the Lyre,

và còn những cuốn khác nữa: tiểu luận dài, là cả 1 cuốn sách, về Mexico

và văn

hóa của nó, Mê Cung của Cô Đơn, và

nghiên cứu có tính tiểu sử của nhà thơ lớn

Mexico, thời kỳ thuộc địa, Sor Juana de la Cruz, và tiểu luận của ông

về

lịch sử

và chính trị, One Earth, Four or Five Worlds, và những tiểu

luận

về nghệ

thuật Mexico. Trong thế hệ thi sĩ cùng thời, chỉ Czeslaw Milosz, tầm

vóc và chiều sâu, ngang ông.

Nhưng trước tiên, và trong tất cả, thì vẫn là thi sĩ Octavio Paz,

[“ông số 1” như Mít có thể gọi, dù "Ông số 1" này thì cũng viết đủ thứ,

khiến ông

tiên chỉ VP mà còn nhầm, và coi là tiểu thuyết gia!] Những

cuốn dịch qua tiếng Anh bảnh nhất, là Tuyển

Tập Thơ, và

A Tree Within. Ở đây, là 1 bài thơ thần sầu,

mà qua bản

tiếng Anh, bạn có thể ngửi ra mùi vị gốc Tây Bán Nhà của nó:

Wind and Water

and Stone

The water

hollowed the stone,

the wind

dispersed the water,

the stone

stopped the wind.

Water and

wind and stone.

The wind

sculpted the stone,

the stone is

a cup of water,

the water

runs off and is wind.

Stone and

wind and water.

The wind

sings in its turnings,

the water

murmurs as it goes,

the

motionless stone is quiet.

Wind and

water and stone.

One is the

other, and is neither:

among their

empty names

they pass

and disappear,

water and

stone and wind.

Gió và Nước và Đá

Nước làm rỗng đá

Gió làm nước tung toé

Đá chặn gió

Nước và gió và đá.

Gió tạc đá

Đá là ly nước

Nước chạy/chảy và là gió

Đá và gió và nước

Gió hát theo từng khúc quanh

của nó

Nước thầm thì khi chảy

Đám bất động lặng câm

Gió và nước và đá

Kẻ này là kẻ kia và chẳng là kẻ

nào:

Giữa những cái tên trống rỗng

Chúng qua đi và biến mất

Nước và đá và gió

Robert Hass: Now & Then

Octavio

Paz

Autumn

The wind wakes,

sweeps the thoughts from my mind

and hangs me

in a light that smiles for no one:

what random beauty!

Autumn: between your cold hands

the world flames.

1933

Octavio Paz: First Poems (1931-1940)

Mùa Thu

Gió thức dậy

Quét những ý nghĩ ra khỏi cái đầu của anh

Và treo anh

Trong ánh sáng mỉm cười cho chẳng ai

Cái đẹp mới dưng không, tình cờ làm sao?

Mùa thu: giữa lòng bàn tay lạnh của em

Tình anh sưởi ấm

[nguyên văn, thế giới bập bùng ngọn lửa]

Here

My footsteps in this street

echo

in another street

where

I hear my footsteps

passing in this street

where

Only the mist is real

[1958-1961]

Đây

Tiếng bước chân của tôi

trong con phố này

vọng lên

trong một con phố khác

nơi

tôi nghe những bước chân của mình

qua con phố này

nơi

Chỉ sương mù là có thực

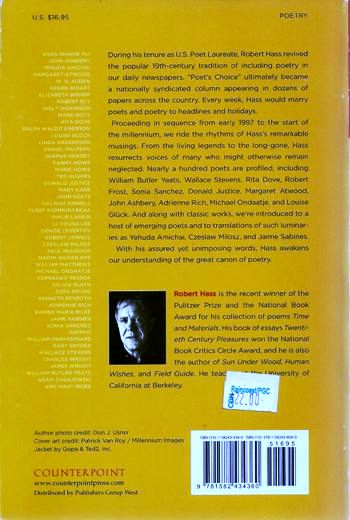

Robert Hass,

nhà thơ với vòng nguyệt quế Mẽo, U.S. Poet Laureate, còn là nhà dịch

thơ số 1,

như những bạn thơ, cũng "U.S. Laureate" như Charles Simic, thí

dụ.

Tin

Văn sẽ đi những bài viết trong này, vì đọc chúng, cũng là đọc thơ toàn

thế giới!

Hà, hà!

Khi GCC phịa

ra mục “thơ mỗi ngày” và được 1 độc giả đi 1 cái mail cám ơn, đã

thấy sướng

mê tơi.

Nhưng mục nhà thơ Robert Hass phịa ra mới khủng, như chính ông thú

nhận,

chưa từng có trên đời:

The

Poet’s Choice Columns.

A Note to

Readers

THIS IS A

BOOK of poems and small essays about them written over a period of

about two

years. It came about because Nina King, then literary editor of the Washington

Post, invited me to write a weekly column for the Post's Book World.

The idea

was that I would, each week, select a poem and comment on it. The aim

was to

introduce poetry to people who had never read it at all; to reintroduce

it to

people who had read it in school but had gotten out of the habit and,

having an

impulse to find their way back to it, didn't know where to start; and

to give

people who did read poetry some poems and ideas about poems to think

about.

The column

was a novelty. Nothing quite like it had been done in an

American

newspaper in

many decades, if ever, and it was immediately popular with readers of

Book

World….

Để ăn mừng tập

thơ, GCC xin giới thiệu tới độc giả TV, bài tưởng niệm Zbigniew

Herbert, Robert

Hass viết, đúng

SN/GCC.

AUGUST 16 [1998]

In Memoriam: Zbigniew

Herbert

Zbigniew

Herbert died a few weeks ago in Warsaw at the age of seventy-three. He

is one

of the most influential European poets of the last half century, and

perhaps-even more than his great contemporaries Czeslaw Milosz and

Wladislawa

Symborska-the defining Polish poet of the post-war years.

It's hard to

know how to talk about him, because he requires superlatives and he

despised

superlatives. He was born in Lvov in 1924. At fifteen, after the German

invasion

of Poland, he joined an underground military unit. For the ten years

after the

war when control of literature in the Polish Stalinist regime was most

intense,

he wrote his poems, as he said, "for the drawer." His first book

appeared in 1956. His tactic, as Joseph Brodsky has said, was to turn

down the

temperature of language until it burned like an iron fence in winter.

His verse

is spare, supple, clear, ironic. At a time when the imagination was, as

he

wrote, "like stretcher bearers lost in the fog," this voice seemed

especially

sane, skeptical, and adamant. He was also a master of the prose poem.

Here are

some samples:

The Wind and the Rose

Once in a

garden there grew a rose. A wind fell in love with her. They were

completely different,

he-light and fair; she immobile and heavy as blood.

There came a

man in wooden clogs and with his thick hands he plucked the rose. The

wind

leapt after him, but the man slammed the door in his face.

-O that I

might turn to stone-wept the unlucky one-I was

able to go round the whole world, I was

able to stay away for years at a time, but I knew that she was always

there

waiting.

The wind

understood that, in order really to suffer, one has to be faithful.

Mưa

Khi ông anh của tớ từ mặt

trận trở về

Trán của anh có 1 ngôi sao bạc nho nhỏ

Và bên dưới ngôi sao

Một vực thẳm

Một mảnh bom

Đụng anh ở Plê Ku

Hay, có lẽ, ở Củ Chi

(Anh quên những chi tiết)

Anh trở thành nói nhiều

Trong nhiều ngôn ngữ

Nhưng anh thích nhất trong tất cả

Ngôn ngữ lịch sử

Đến hụt hơi,

Anh ra lệnh đồng ngũ đã chết, chạy

Nào anh Núp,

Nào anh Trỗi.

Anh la lớn

Trận đánh này sẽ là trận chiến thần thánh chót

[Mỹ Kút, Ngụy Nhào, còn kẻ thù nào nữa đâu?]

Rằng Xề Gòn sẽ vấp ngã,

Sẽ biến thành Biển Máu

Và rồi, xụt xùi, anh thú nhận

Bác Hồ, lũ VC Bắc Kít đếch ưa anh.

[Hà, hà!]

Chúng tôi nhìn anh

Ngày càng xanh mướt, tái nhợt

Cảm giác bỏ chạy anh

Và anh lần lần trở thành 1 đài tưởng niệm liệt sĩ

Trở thành những cái vỏ sò

âm nhạc của những cái tai

Đi vô khu rừng đá

Và da mặt anh

Thì được bảo đảm bằng những cái núm mắt khô, mù

Anh chẳng còn gì

Ngoại trừ xúc giác

Những câu chuyện gì, anh kể

Với những bàn tay của mình.

Bên phải, những câu chuyện tình

Bên trái, hồi ức Anh Phỏng Giái

Chúng mang ông anh của tớ

đi

Đưa ra khỏi thành phố

Mỗi mùa thu anh trở về

Ngày càng ốm nhom, mỏng dính

Anh không muốn vô nhà

Và đến cửa sổ phòng tớ gõ

Hai anh

em đi bộ trong

những con phố Xề Gòn

Và anh kể

cho tớ nghe

Những câu

chuyện chẳng đâu vào đâu

Và sờ mặt

thằng em trai của anh

Với những

ngón tay mù,

Của mưa.

Zbigniew

Herbert

AUGUST 16 [1998]

In Memoriam: Zbigniew

Herbert

Zbigniew

Herbert mất vài tuần trước đây, ở Warsaw thọ 73 tuổi. Ông là 1 trong

những nhà

thơ Âu Châu, ảnh hưởng nhất trong nửa thế kỷ, và có lẽ - bảnh hơn

nhiều, so với ngay cả hai người vĩ đại, đã từng được Nobel, đồng thời,

đồng hương với ông, là Czeslaw Milosz và

Wladislawa

Symborska - nhà thơ định nghĩa thơ Ba Lan hậu chiến.

Thật khó mà

biết làm thế nào nói về ông, bởi là vì ông đòi hỏi sự thần sầu, trong

khi lại

ghét sự thần sầu. Ông sinh tại Lvov năm 1924. Mười lăm tuổi, khi Đức

xâm lăng

Ba Lan, ông gia nhập đạo quân kháng chiến. Trong 10 năm, sau chiến

tranh,

khi chế độ

Xì Ta Lin Ba Lan kìm kẹp văn chương tới chỉ, ông làm thơ, thứ thơ mà

ông nói, “để

trong ngăn kéo”.

*

Zbigniew Herbert, “Ba Lan Tam

Kiệt” [hai “kiệt” còn lại là,

Milosz, Szymborska đều đợp Nobel văn chương], như "Đồng Nai Tam Kiệt"

của xứ Mít Nam: Bùi Giáng, Tô Thuỳ Yên, Thanh Tâm Tuyền, như NTV đã

từng gọi.

Gấu biết tới Herbert, là qua 1 bài viết của Coetzee, "Thế nào là cổ

điển?" (1)

Nhưng để đọc được ông, thì cũng mới đây thôi, một phần vì cuốn nào của

ông thì

cũng dày cộm, và vì ông là thi sĩ, mà cái món thi sĩ, thì Gấu cũng mới

đọc

được, mới đây thôi!

Đọc 1 phát, là dịch ào ào, điếc không sợ súng!

(1)

Nhà văn Nam Phi [Coetzee]

nhắc tới một bài diễn thuyết -

cùng tên với bài viết của ông, của T.S. Elliot - vào tháng Mười 1944,

tại

London, khi Đồng Minh đang quần nhau với Nazi tại đất liền (Âu Châu).

Về cuộc chiến, Eliot chỉ nhắc tới nó, bằng cách xin lỗi thính giả, rằng

chỉ là

tai nạn của hiện tại (accidents of the present time), một cái hắt hơi,

xỉ mũi,

đối với cuộc sống của Âu Châu, và nó làm ông không thể sửa soạn chu đáo

cho bài

nói chuyện.

"Nhà là nơi một người bắt đầu"

[Home is where one starts

from], "Trong cái bắt đầu là cái chấm dứt của tôi" [In my beginning

is my end], nhà thơ [Eliot] cho rằng, để trả lời cho câu hỏi này, chúng

ta phải

trở lại với nhà thơ lớn lao nhất, "cổ điển của chính thời đại của chúng

ta" (the great poet of the classic of our own times), tức nhà thơ Ba

Lan,

Zbigniew Herbert.

Với Herbert, đối nghịch Cổ Điển

không phải Lãng Mạn, mà là Man Rợ.

Với nhà thơ Ba Lan, viết từ mảnh đất văn hóa Tây Phương không ngừng

quần thảo

với những láng giềng man rợ, không phải cứ có được một vài tính cách

quí báu

nào đó, là làm cho cổ điển sống sót man rợ. Nhưng đúng hơn là như thế

này: Cái

sống sót những xấu xa tồi tệ nhất của chủ nghĩa man rợ, và cứ thế sống

sót, đời

này qua đời khác, bởi những con người nhất quyết không chịu buông xuôi,

nhất

quyết bám chặt lấy, với bất cứ mọi tổn thất, (at all costs), cái mà con

người

quyết giữ đó, được gọi là Cổ Điển.

Như vậy, với

chúng ta, cuộc chiến vừa qua, cũng

chỉ là một cái hắt hơi của lịch sử. Không phải viết từ những đối nghịch

chính

trị, như một hậu quả của cuộc chiến đó, mà trở nên bền. Muốn bền, là

phải lần

tìm cho được, cái gọi là nhà, liệu có đúng như Eliot nói đó không: Nhà

là nơi

một người bắt đầu.

Hay nhà là

nơi cứ thế sống sót những xấu xa của

chủ nghĩa Man Rợ, đời này qua đời khác, bởi những con người nhất quyết

không

chịu buông xuôi, nhất quyết bám chặt lấy, với bất cứ mọi tổn thất...

Câu trên, Nhà là nơi một người bắt đầu, có vẻ như áp dụng cho một nhà

văn Việt

nam ở hải ngoại.

Câu dưới, có

vẻ như dành cho nhà văn trong nước.

|

|