|

|

GCC có mấy số

ML về Flaubert, số trên chắc là mới nhất. Trong có bài “Nghệ Thuật

Khinh Bỉ” đọc

cũng thú: Mặc dù văn phong khách quan, cuốn tiểu thuyết của Flaubert

nằm trong

truyền thống văn chương miêu tả những bất hạnh của cái xấu, cái ác, les

malheurs du vice. “Bà Bô” phải gợi ra lòng thương hại lẫn khinh khi,

nhưng

Flaubert không hề có ý định viết văn để ăn mày nước mắt độc giả, những

kẻ mủi

lòng vì số phận người đàn bà ngoại tình, mặc dù những bất hạnh giáng

xuống đời

Bà.

Số báo còn

hai bài, cũng thật tuyệt. “Sổ Đọc” của Vila-Maltas: Monsieur Mantra,

"l'irréalisme magique " de Rodrigo Fresán, và bài của Linda Lê,

trong

mục “Trở về với những tác giả cổ điển”: "Les Griffes du passé, Những

móng nhọn của quá khứ.

Hai mục này, Gấu

đều mê, nhưng sau này đều bị tờ ML bỏ đi.

Tiếc!

[Thuổng văn phong của Thầy Kuốc: Thích!]

Số Mùa

Hè,

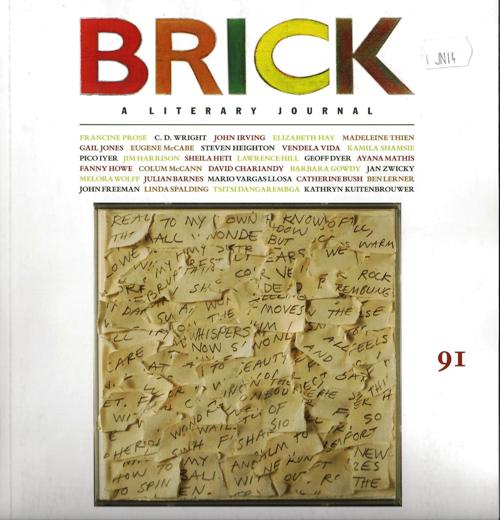

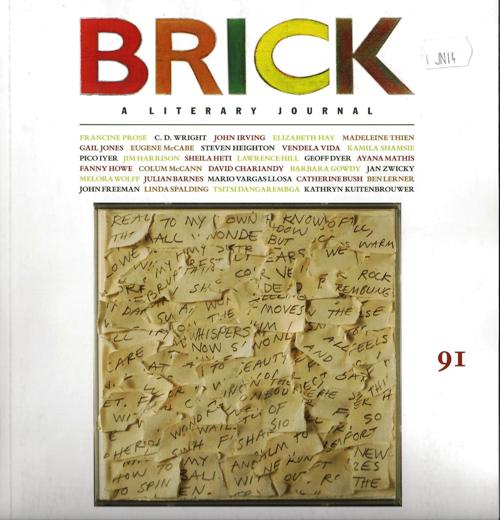

2013. Báo nhà [Toronto]. Nhiều bài tuyệt lắm, hà hà!

Nhẩn nha đi vài đường, sau.

Một trong những đề tài của số này, là về

“cái gọi là”

kết thúc, the end, của 1 cuốn tiểu thuyết.

Flaubert

JULIAN BARNES

MARIO VARGAS

LLOSA

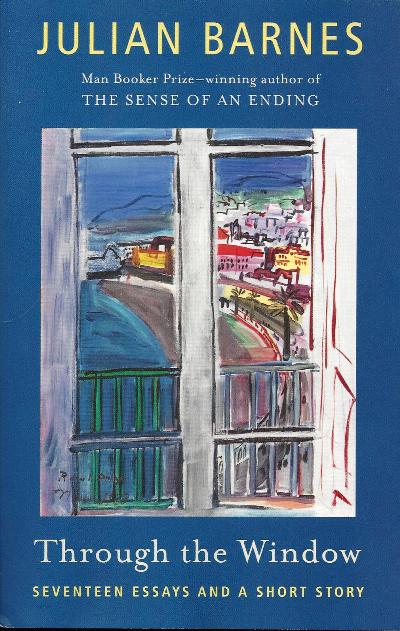

Note: Đọc

bài này, thì cũng nên đọc thêm bài Julian Barnes viết, trong tập tiểu

luận của

ông, Qua Cửa Sổ, Through the Window:

"Dịch Madame Bovary", Translating

Madame Bovary

[qua tiếng Anh]. Trong bài viết, ông có chê

bản dịch

mới của em Lydia Davis, được coi là 1 trong những chuyên gia về

Flaubert. Bà này, trên

1 số Paris Review, Fall, 2010, có đi mấy truyện ngắn, phỏng

theo

Flaubert, After Flaubert.

At the Hay

Festival if Literature and the Arts twenty years ago, Julian Barnes and

Mario

Vargas Llosa met to talk about Gustave Flaubert. In January 2013 at Hay

Festival Cartagena de Indias in Colombia, they discussed their hero

again-and

found that he had changed almost as much as they had. Marianne Ponsford

moderated their conversation.

Note: Hai

ông học trò, một ông Booker, một ông Nobel, vinh danh Thầy, cùng lúc,

viết về mối

tình của cả hai, với cùng 1 em bướm, Madame Bovary.

Flaubert

cried out against the paradox whereby he lay dying like a dog whereas

that

‘whore’ Emma Bovary, his creature… continued alive.

G. Steiner, The Uncommon Reader.

Flaubert la

lên, tại sao ‘con điếm’ Bovary cứ sống hoài, trong khi ta nằm đây, chết

như một

con chó ghẻ?

“Cái

chết của Lucien de Rubempré là một bi kịch lớn, the great drama, trong

đời tôi”, Oscar Wilde nhận xét về một trong những nhân vật của Balzac.

Tôi luôn coi lời phán này, this statement, là thực, literally true. Một

dúm nhân vật giả tưởng đã ghi dấu thật đậm lên đời tôi hơn những con

người bằng xuơng bằng thịt, bằng máu bằng mủ mà tôi đã từng quen biết.

Llosa

mở ra cuốn tiểu luận của mình The

Perpetual Orgy, "Đốt đuốc chơi... Em", như trên.

Cả một cuốn tiểu luận, dành cho Em Bovary, chưa đủ, sau ông còn viết cả

một cuốn tiểu thuyết, Gái Hư, The Bad

Girl, để vinh danh Em!

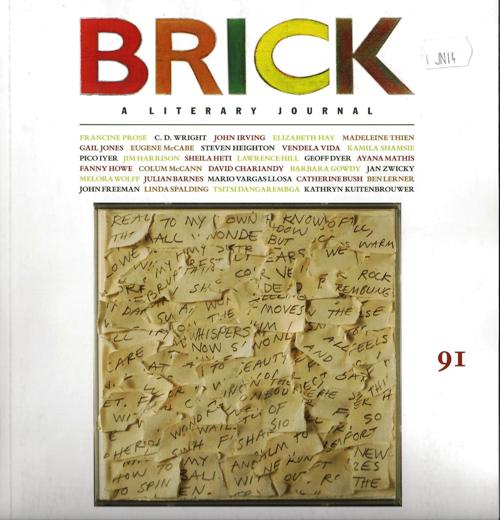

Số báo Brick,

trên, gồm bài viết của 44 tác giả

viết về cái hậu, the end, của 1 cuốn tiểu thuyết; Madeleine Thien, chắc

là Mít,

ở Montreal, phỏng vấn Tsiti Dangaremba, về cuốn tiểu thuyết đầu tay

thần sầu của

em này, hai ông nhà văn thổi bướm Bovary….

Trong 44 tác

giả, chưa có ai từng đọc Lukacs, theo Gấu, bởi là vì, Lukacs là người

đưa

ra 1 nhận định cực

thần sầu về cái kết, của 1 cuốn tiểu thuyết:

Đó là lúc ý thức của tiểu

thuyết

gia vượt ý thức của nhân vật chính, để tìm lại đời sống thực.

Trong bài viết về Bếp Lửa, 1972, Gấu

“đế” thêm: Đây là hình ảnh Lưu Nguyễn về trần, bởi là vì, mỗi một

cuốn tiểu thuyết lớn, thì là 1 câu chuyện thần tiên, đúng như Nabokov

phán, khi

viết về Madame Bovary của Flaubert.

Cả cuốn Bếp

Lửa [cuộc sống của anh chàng Tâm trong "Bếp Lửa"], thật khệnh

khạng [đi ra ngoài

đó - lên rừng, theo VC – thì cũng chỉ là 1 thứ đánh đĩ], thật kịch cợm,

thật trí

thức, thật siêu hình [giả như Thượng Đế mà nhập thân trong xác phàm,

thì cũng từ

chết đến bị thương, từ thua cho tới thua, và chỉ thoát ra bằng sự thất

bại], một

câu chuyện "thần tiên", kết bằng 1 câu thật cảm động, thật sến, mà tất

cả

lũ Mít

đều thèm nghe:

Anh yêu quê

hương vô cùng và anh yêu em vô cùng.

Trong 44 tác

giả, tuyệt nhất với Gấu, là Pico Iyer, viết về kết thúc của Người Mỹ

Trầm Lặng của

Graham Greene.

Pico

Iyer mở

ra bài viết bằng 1 câu, qua đó, có vẻ như cũng thật mê

Greene (1)

Tôi mất cả nửa

đời mình để nhập vô cuốn phúc âm nhức nhối của Graham Greene về nhân

loại.

It took me

half a life time to grow into Graham Greene’s anguished gospel of

humanity.

Tuyệt!

Tờ Brick

viết về Pico Iyer:

Pico Iyer cố

làm bật G.G khỏi hệ thống của mình bằng cách viết ba ngàn trang về G.G,

tới cuốn

mới nhất: “Người đàn ông trong đầu tôi”. Nhưng vưỡn thua.

Pico Iyer

tried to get Graham Greene out of his system by writing three thousands

pages

on him, boiled down into his most recent book, The Man Within My Head

(a). He still

failed

“Writing is,

in the end, that oddest of anomalies: an intimate letter to a stranger.”

Viết, quái nhất trong những quái: Lá thư riêng tư cho... một kẻ lạ,

người dưng, nước lã!

― Pico Iyer

“Perhaps the

greatest danger of our global community is that the person in LA thinks

he

knows Cambodia because he's seen The Killing Fields on-screen, and the

newcomer

from Cambodia thinks he knows LA because he's seen City of Angels on

video.”

Cái nguy hiểm

nhất của cộng động toàn cầu, là, ngồi ở LA phán, tớ biết Cam bốt, vì

mới xem

phim “Cánh đồng giết người”. Và 1 tên Cam bốt mới nhập Mẽo phán, tớ

biết LA, vì

mới coi video “Thành phố của những thiên thần”

― Pico Iyer (1)

“Ông số 2”, ngồi ở Quận Cam, chẳng đã ngậm ngùi phán, Sài Gòn có người

chết đói, ngay bên hông Chợ Bến

Thành!

(a)

The Man

Within My Head by Pico Iyer

We all

carry

people inside our heads—actors, leaders, writers, people out of history

or

fiction, met or unmet, who sometimes seem closer to us than people we

know.

In The Man

Within My Head, Pico Iyer sets out to unravel the mysterious

closeness he has

always felt with the English writer Graham Greene; he examines Greene’s

obsessions, his elusiveness, his penchant for mystery. Iyer follows

Greene’s

trail from his first novel, The Man

Within, to such later classics as The Quiet

American and begins to unpack all he has in common with Greene:

an English

public school education, a lifelong restlessness and refusal to make a

home

anywhere, a fascination with the complications of faith. The deeper

Iyer

plunges into their haunted kinship, the more he begins to wonder

whether the

man within his head is not Greene but his own father, or perhaps some

more

shadowy aspect of himself.

Drawing upon

experiences across the globe, from Cuba to Bhutan, and moving, as

Greene would,

from Sri Lanka in war to intimate moments of introspection; trying to

make

sense of his own past, commuting between the cloisters of a

fifteenth-century

boarding school and California in the 1960s, one of our most

resourceful

explorers of crossing cultures gives us his most personal and

revelatory book.

It is still

beautiful to feel the heart beat

but often

the shadow seems more real than the body.

The samurai looks insignificant

beside his

armor of black dragon scales.

Thì

vưỡn đẹp khi cảm thấy trái tim đập

Nhưng thường là cái bóng có

vẻ thực hơn cơ thể

Vì samurai xem ra chẳng có ý

nghĩa gì

Bên cạnh bộ giáp với những vẩy

rồng đen thui của ông ta.

Note: Bài thơ thần sầu.

Gửi theo ông anh quá tuyệt. Bảy năm rồi, xác thân nào còn, linh hồn thì

cũng có khi đã đầu thai kiếp khác, hoặc tiêu diêu nơi miền cực lạc.

Nhưng cái bóng thì lại càng ngày càng lớn, dội cả về Đất Cũ:

VC bi giờ

coi bộ trân

trọng cái bóng của ông cùng cái áo giáp, mấy cái vảy rồng đen thui, còn

hơn cả đám bạn quí hải ngoại của ông! (1)

Nhẩn nha đi vài đường, sau. Một trong những đề tài của số này, là về

“cái gọi là”

kết thúc, the end, của 1 cuốn tiểu thuyết.

Flaubert

JULIAN

BARNES

MARIO VARGAS

LLOSA

At the Hay

Festival if Literature and the Arts twenty years ago, Julian Barnes and

Mario

Vargas Llosa met to talk about Gustave Flaubert. In January 2013 at Hay

Festival Cartagena de Indias in Colombia, they discussed their hero

again-and

found that he had changed almost as much as they had. Marianne Ponsford

moderated their conversation.

Ponsford:

What has changed for you in your appreciation of Flaubert in the past

twenty

years?

Barnes:

I

suppose there are two parts to the answer: what has changed with

Flaubert, and

what has changed with me. Rather surprisingly, Flaubert, despite being

dead for

133 years, is still changing. That's to say, the corpus is still

expanding. In

the last twenty years, the magnificent Pleiade edition of the Correspondance

has been completed, and so we can now read almost every single letter

of his

that has survived. And the correspondence is the place to find Flaubert

the

human being and is to be read side by side with the novels. It's a

great work

of art in itself. Other things that have been published: the Pléiade

produced

the Oeuvres de jeunesse for

the first time in a complete

format-everything he

published before Madame Bovary.

It's a fat volume that has more words

in it

than all the books he published in his lifetime. And it also proves

that if

Flaubert had died in 1850 or 1851, before he'd started writing Madame

Bovary,

no one would say, We have lost a genius.

Also what

has changed with Flaubert is new translations-some of them are an

improvement

and some of them are not. I don't follow the academic discourse, but in

the

world of amateur Flaubert scholarship amazing books keep coming out.

One

arrived on my desk the other day: it is a dictionary of all the words

that

appear in Madame Bovary. In

order. Every time the word crops up, it is

listed.

So you get “I” and you have “la” and “le” and "lui," and there are

eleven pages, each of six columns-2,027

entries in all-going "la la la la la"-like we're in a demented opera

house. You look at it and you think, What is this for? There's a very

French

introduction to it, which says, This is perhaps a work suited to the

Oulipo

school, whereby if we put all the words of Madame

Bovary into a book, in alphabetical order, you the reader can then

manufacture

your own novel using only the words that are in the original. Crazy, or

what?

So that's

how Flaubert has changed. For myself, I continue

to read him, and I find that I do read the books differently, still. I

go back

the most often to Madame Bovary, and I still find, in its

adamantine

perfection, that there are new things to discover, things I had not

noticed

before. Bouvard et Pecuchet now

stands clearer and greater

in my mind because I think I'm beginning finally to understand what

it's about. It's not a

book to read when you're a young man.

Llosa: No.

Barnes: So partly he's changed,

and partly

I've changed.

Llosa: I'd like to add a

footnote to what

Julian said. It's a fact I read not long ago and which pleased me

enormously.

It was about the number of critical works generated by French authors

worldwide,

and Flaubert came' out third. After Victor Hugo and Montaigne, it was

Flaubert

who produced the most critical works, university theses, essays,

scholarly

tomes. And on the personal front: I continue to reread, sometimes

fragments, of

Flaubert, and he is a writer who has never disappointed me and has

always moved

me. I even reread scenes that are already very clear in my mind, some

of themfor

their literary intelligence. The scene I always reread-and particularly

when I’m

depressed-is Madame Bovary's suicide. For a

strange reason, which a psychoanalyst could no doubt explain to me one

day. Why

is it that that scene, which is so atrociously sad, the scene in which

Madame

Bovary swallows the arsenic, and there's that truly chilling

description of

what happens to her face, her mouth, her tongue ... How is that a scene

that

draws me out of my own misery and demoralization and makes me feel

somehow

reconciled to life? I'm not joking. In periods of great depression in

my life

I've gone back to read the suicide scene in Madame

Bovary-and the perfection, the mastery, the beauty with which that

horror

is described is so great that I feel an injection of enthusiasm, a

justification

for life itself. Life is worth living, if only to read the sort of

skill to be

found in those pages –the extraordinary lucidity, intelligence,

dexterity,

intuition with which he was able to bring to life a scene which, told

straight,

would produce a rejection of and a distaste for life. Julian, does that

scene

have the same emotional effect on you?

Barnes:

Um,

I don't go to it when I'm depressed. I think I'd turn to music rather

than

literature. But I think I'm a Simpler and less perverse human being

than you

are. But going back to what we were saying about how Flaubert has

changed and

how he's viewed. I've been thinking about how when you and I first read

him, he

was really rather unfashionable. I think he was a victim of political

correctness from the Left, partly because he said harsh things about

the

Commune, and partly because he was after all a rentier. He didn't

really live

off his writing, he lived off the income from his family and property

and so

on, and he could be dismissed as a bourgeois-in fact he was resolutely

anti-bourgeois. Fifty years ago he was read in schools, but afterwards

you were

sort of meant to forget him.

Llosa:

I

remember that atrocious phrase of Sartre's against Flaubert: "I hold

Flaubert responsible for the crimes committed against the Communards,

because

he never wrote a word condemning them." Which reveals very well that

rejection of Flaubert by the Left at a certain moment.

Barnes:

Yes.

It was political, and it was also aesthetic. In his autobiography, Les

Mots,

Sartre writes of being "poisoned by the old bile" of Flaubert and

Edmond de Goncourt and Theophile Gautier. They were the enemy, who had

to be

wiped from the battlefield. I've only read the first of his three

volumes about

Flaubert, L'Idiot de la famille, and it's a kind of monstrous work.

It's always

struck me as an attempt to bury Flaubert. As if he said, I'm going to

erect

this enormous monument to Flaubert, which will be so vast, and so

Sartrean,

that everyone will forget who's buried underneath. But he failed.

Llosa:

Even

Sartre recognized that Flaubert was the first modern novelist, in the

sense

that he gave rise to a certain model of novel that continues to this

day. There

were great novelists in the nineteenth century, but they didn't enrich

the

novels of the future in the way that Flaubert's teachings did. He

created a

whole technique for the invisibility of the narrator-a commitment to

finding

the exact word, so that the reader was not distracted either by exact

word or

by absence. We have to rearrange our sense of realism when we anything

published earlier. The contemporary novel was born with Flaubert, and

in that

sense all novelists are Flaubertians now, whether we like Flaubert or

not.

Barnes:

Yes,

I'd agree with all of that, and I'd add his clever and subtle use of

irony, and

his deployment of the style indirect libre, which he developed to a

point of

perfection that had not been there before. Also, he was, for me, the

novelist

who promoted the absolute importance of form in the novel. If we

compare the

Flaubertian method with what British novelists were doing at the

time-Dickens,

Thackeray, Trollope, George Eliot-there's one practical difference.

Their

novels mostly appeared first in monthly parts, and they would write

them as

they went along. They would be, essentially, brilliant episodes which

were then

bound up into a novel. I think a lot of novelists, pre- and

post-Flaubert, have

a very loose and fuzzy sense of what form is. Some think it's just

telling a

story, and going along until it ends-that structure is only important

when

writing a sonnet or something. I remember the wonderful thing that

Virginia

Woolf said about Dickens. She compared a Dickens novel to a blazing

fire, which

sometimes seems to be dying down, whereupon Dickens suddenly creates a

perfectly formed new character and chucks him or her onto the fire,

which

blazes up again and the novel takes off. Which is responding to the

particular

needs of writing weekly episodes.

Although Madame

Bovary was

published in the Revue de

Paris in periodical form, Flaubert had already finished it, and

he never

published anything until it was formally complete. What I see

increasingly as I

understand more about novels and write more novels is the way in which

things

are held together. For example, there's a tiny character in Madame

Bovary called Justin. He's the

assistant to Monsieur Homais, the

pharmacien. The main function of Justin in the book is to help

Madame

Bovary steal and swallow the arsenic. And when you read the book for

the first

time, that's probably the only time you properly take account of him.

But

Justin is there for three-quarters of the novel in very tiny

touches-often seen

in doorways looking at scenes. All these touches, when put together,

add up to

a sort of parallel seduction, and parallel corruption, of Justin by

Emma. At the

end, he's the person who is seen weeping on her grave. His presence,

and his

subtle underlinings, are a way of stitching the novel together, which

you can

do only if you have a great sense of architecture. And great architects

sometimes design the door handles as well as the walls.

Llosa:

I'd

like to touch on another aspect of Flaubert, which is his attempt to

achieve the

impossible. I think that Bouvart et Pécuchet is a

novel which proposes to do something unachievable,

a novel that is

born condemned to disaster. But it has aspired to so much and gone so

far, that

even though it doesn't reach its goal, the work is extraordinary,

unusual.

Well,

there's a thread in modern literature that is in some way encapsulated

by that

insane attempt of Flaubert's to write a novel that synthesized all the

knowledge

of his time. Joyce-a great admirer of Flaubert, as

were Proust and Kafka-wrote, after he finished Ulysses,

Finnegan Wake, a novel that is almost impossible to read

and impossible to finish. In Spanish we have

Paradiso, by Lezama Lima. I think that had never happened before

Flaubert-a

truly great, unfinished, and frustrated masterpiece like

Bouvard et Pécuchet. That too is a branch of his influence.

Ponsford :

I'd like to return to Madame Bovary, the character.

She was a

frivolous, vain-

Llosa: No! I protest!

Ponsford: -irresponsible, volatile

woman-

Llosa: That's a lie. Slander!

Barnes: Mario-

Llosa:

No,

wait! I'm going to defend Madame Bovary! She

was just a young girl who read romantic fiction. And she thought that

life was

as it was depicted in novels. And her tragedy, her drama, is that she

wanted to

turn that fiction into reality. Like Quixote-who read books about

chivalry,

thought life was as it was in those, and set out to transform reality

into

something resembling fiction. That's what Madame Bovary does. She wants

life to

be made of extraordinary passions that lead one to have great

adventures, she

wants life to be about pleasure-the pleasure of elegance, of

extravagance, of

sensuality; the pleasure of the sentimental excesses of passion. That's

what

she wants to bring about with her deeds, and what does she find all

around her?

Mediocrities- poor devils who are incapable of living at the level of

sensitivity

and imagination that she has been taught by fiction. That's the great

symbolism

of Madame Bovary, what makes it not

just a little realist novel but a novel that expresses a fundamental

element of

the human condition: our inability, as human beings, to accept reality

as it

is. Our profound need to live in another way-not to have just this one

life.

It's why we read fiction. Throughout history there have been people

like Don

Quixote and Madame Bovary, and the world has changed and progressed:

we've come

out or the caves and reached the moon, thanks to those crazy fools.

Madame

Bovary wasn't frivolous. She was a

great dreamer, a great rebel, an absolutely extraordinary and admirable

woman.

Barnes: I had failed to inform

our

moderator that Mario has

been in love with Emma Bovary for forty or fifty years.

Llosa: It's true, absolutely.

Barnes: I too react-though not

with quite

such personal feeling as you do-when readers complain that Madame

Bovary is a

trivial person. She is the only person in the novel who attempts to

extract herself

from her circumstances. She's the only person who acts with boldness

and

courage, in difficult social circumstances for a woman. The men in

Madame

Bovary are all cowards. She is not a coward, either in love or in sex,

and they

don't measure up to her. People sometimes say, "I don't like Madame

Bovary."

Someone even complained to me that she was" a bad mother." And you

think: What's that got to do with anything? You know, Hamlet: he

couldn't make

up his mind. King Lear: mad as a hatter. You don't go to great

literature in

order to like people, to find chums. This is the Oprah-fication of

literature.

But I yield to you, Mario, in your passion for Madame Bovary. I respect

her, I

admire her, I might even fancy her, but you can have her in that

carriage.

|

|