|

|

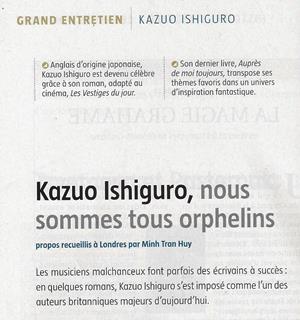

Note: Kiếm ra số báo ML có

bài "đại phỏng vấn" Kazuo Ishiguro, do Trần Minh Huy thực hiện: Tôi

chưa từng có ý làm 1 tiểu thuyết gia, cho tới năm 23 tuổi, bất thình

lình phán 1 phát, mình phải viết về xứ Nhựt Lùn. Bài phỏng vấn tuyệt

lắm. GCC sẽ đi 1 đường chuyển ngữ, để cho thấy, không phải là cứ đeo

kiếng vô - viết bằng tiếng mũi lõ - là có văn chương.

Thành tựu của cuộc

ăn cướp Miền Nam chỉ đẻ ra 1 thứ nhà văn "rửa bướm như rửa rau"!

Kazuo Ishiguro

His first

novel, A Pale View of Hills won the 1982 Winifred Holtby Memorial

Prize. His

second novel, An Artist of the Floating

World won the 1986 Whitbread Prize. Ishiguro received the 1989 Man

Booker prize

for his third novel The Remains of the Day. His fouth novel, The

Unconsoled won

the 1995 Cheltenham Prize.

His novels:

An Artist of the Floating World (1986), When We Were Orphans (2000),

Never Let

Me Go(2005) were all shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize.(less)

Thầy của KI, là Dos

Quotes by Kazuo Ishiguro

“There

was another life that I might have had, but I am having this one.”

― Kazuo Ishiguro

tags: inspirational, missed-chances

2643 likes

like

“Memories,

even your most precious ones, fade surprisingly quickly. But I don’t go

along

with that. The memories I value most, I don’t ever see them fading.”

― Kazuo Ishiguro, Never

Let Me Go

tags: memory

2100 likes

like

“I

keep thinking about this river somewhere, with the water moving really

fast.

And these two people in the water, trying to hold onto each other,

holding on

as hard as they can, but in the end it's just too much. The current's

too

strong. They've got to let go, drift apart. That's how it is with us.

It's a

shame, Kath, because we've loved each other all our lives. But in the

end, we

can't stay together forever.”

― Kazuo Ishiguro, Never

Let Me Go

“There

was another life that I might have had, but I am having this one.”

Note:

Câu này, giống thơ GCC:

Không

phải tiếc cuộc đời đã sống

Mà cuộc đời bỏ lỡ, nhớ hoài

Chúng ta viết cho ai?

hay là

Cái kệ sách giả dụ

Note Bài này, GCC mới kiếm

thấy, nhưng lại không biết ai là tác giả. Mò mãi mới ra: Italo Calvino.

Bài tuyệt hay. Nó giải thích được cái sự tha hóa của đám nhà văn Mít,

chê tiếng Mít, viết bằng tiếng mũi lõ: Đếch có mảnh đất nào an toàn cả.

Tác phẩm, chính nó, là 1 trận địa.

Đám khốn này, biết tỏng ra là đếch ai thèm đọc chúng, trừ đám bạn bè

quanh quẩn cũng mất gốc như chúng.

Tàn Ngày

Trong “Những

đứa trẻ của im lặng”, Michael Wood có 1 bài thật “căng”, về Tàn Ngày.

Cách đọc sách của ông, là từ hai bậc đại sư phụ trong giới phê bình,

một, đại

phê bình gia “Trùm” Mác Xít, G. Lukacs, và một, “Trùm” Cơ cấu luận, Ký

hiệu học,

và là người đỡ đầu, phát ngôn viên của trào lưu Tiểu Thuyết Mới ở Tẩy –

còn là vị Thầy

“hụt” của Thầy Kuốc [hụt, theo nghĩa, phịa ra] - Roland Barthes.

Bài này

“kinh” lắm. Hắc búa lắm. Thực sự là vậy. Diễn ngôn của những kẻ khác: The Dicourse of Others.

Tàn Ngày

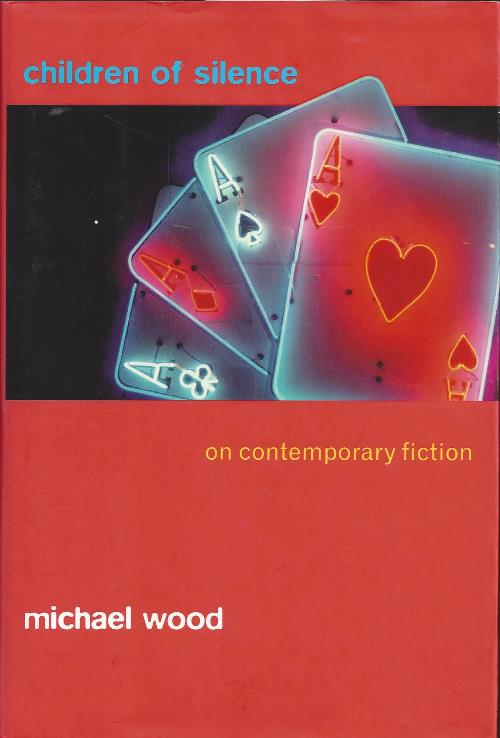

V/v Đeo kiếng vô thì đọc

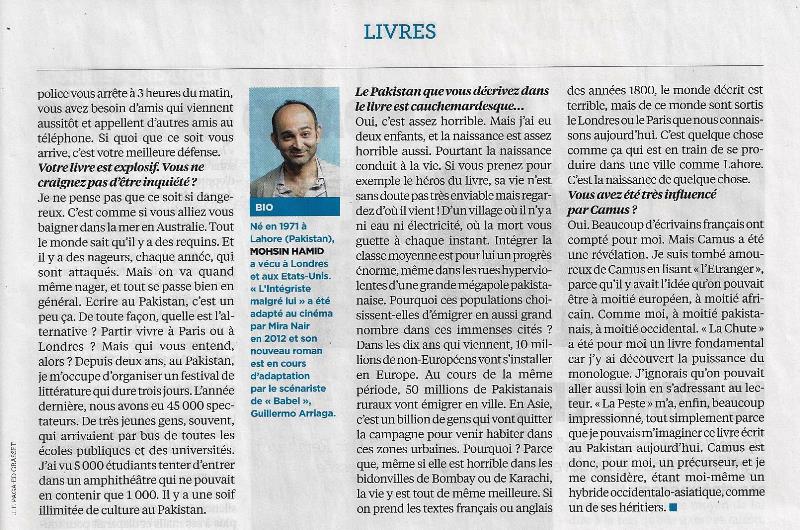

được chữ: Viết văn bằng tiếng của tụi mũi lõ. Tờ Obs, số 28 Aout & 3 Sept giới

thiệu một anh gốc Pakistan, viết văn bằng tiếng Hồng Mao, nhưng sư phụ

của anh, là Camus. GCC

dịch 1 khúc ở trên, là để tặng lũ Mít, Bắc Kít, đúng hơn, chạy thoát

được cái sân gà vịt ở Hà

Nội, nhờ ăn cướp được Miền Nam cho chúng cơ hội, đừng viết dơ bẩn quá.

Cứ vạch

cái đó ra rửa rửa, rồi viết viết, thì quá tởm!

Ông quá bị ảnh hưởng bởi…

Cà Mâu [Cà Mâu là quê hương của Cô Tư]?

Đúng như thế. Rất nhiều nhà văn Tẩy đáng kể đối với tôi. Nhưng Camus là

1 mặc khải. Tôi mê ông ta, je suis tombé amoureux de Camus, khi đọc “Kẻ

Xa Lạ”, bởi cái ý tưởng, người ta có thể nửa Âu, nửa Phi. Như tôi, nửa

Pakistan, nửa Tây Phương. “Sa Đọa”, đối với tôi, thật cơ bản,

fondamental, bởi là vì tôi khám phá ra sức mạnh, quyền năng, la

puissance, của độc thoại. Tôi không hề biết, trước đó, là người ta có

thể đi xa tới mức như thế, trong cái chuyện lèm bèm với độc giả. “Dịch

Hạch” quá ấn tượng đối với tôi, giản dị bởi cái điều, bây giờ, vào thời

điểm này, tôi có thể tưởng tượng, cuốn tiểu thuyết có thể viết ra ở

Pakistan. Camus, như thế, đối với tôi, là 1 kẻ tiền thân, và tôi tự coi

mình, như 1 con vật lưỡng thê, như 1 trong những kẻ thừa kế của ông ta.

Về Kazuo

Ishiguro: The

master craftsman: 10 things you need to know about Kazuo Ishiguro (Sunday London Times

31-8-14) - Ai

chưa đọc Ishiguro thì nên đọc. Một người Nhật lớn lên bên Anh, viết

tiếng Anh

hay mê hồn!

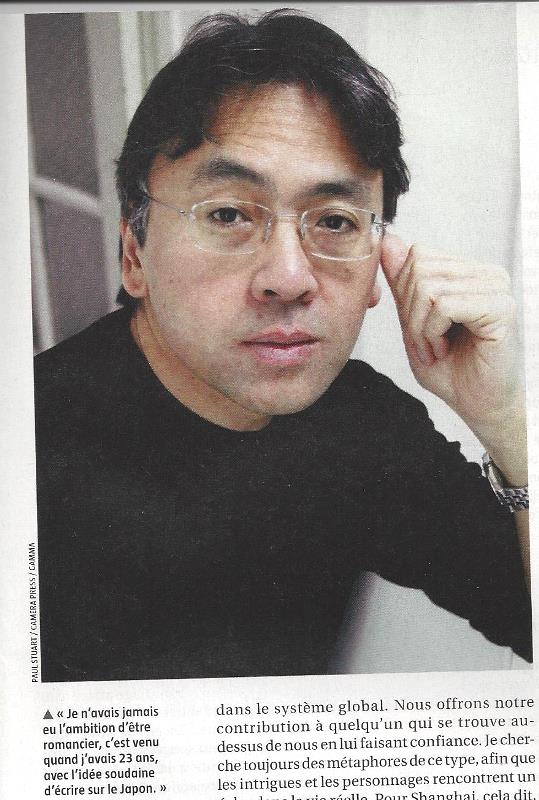

Note: Thấy dòng trên, trên

trang "Vịt Xì Tốp Đi

Thui", của Thầy THD. Bèn bệ về.

Tks. GCC.

[Không biết có phải do Thầy đọc TV, mà cũng lèm bèm về Kazuo

Ishiguo, viết tiếng Anh hay mê hồn!].

Trùm viết văn: 10 điều bạn cần biết về Ông

Trùm. Trong 10

điều, có 1, theo GCC cực thú, do ông Trùm Amazon, 1 fan của KI, phán:

"Trước khi đọc Tàn Ngày, tớ

không tin là có 1 cuốn tiểu thuyết được coi là tuyệt hảo".

Tuyệt. Khen như thế mới là khen! (1)

2. He might be responsible for Amazon

Jeff Bezos, the founder of

Amazon, is a devoted fan of

Ishiguro’s Booker prize-winning 1989 novel, The Remains of the Day. In a 1998

interview, Bezos proclaimed it the most influential book he has ever

read.

“Before reading it, I didn’t think a perfect novel was possible.”

Bezos’s

attachment to the book is so profound that he is rumored to have

decided to set

up an internet bookstore soon after reading it. Even though Bezos’s

wife denies

the story, the fact remains that Ishiguro enjoys the passionate support

of the

world’s most powerful bookseller.

(1)

Lời khen trên,

không giống như bạn quí của GCC, là "Người Đi Trên Mây", thổi Thầy

Kuốc, nhà phê bình

Mít xuất sắc nhất, không phải thời nào cũng có, thí dụ.

Nó làm độc giả nhớ tới

Borges, và giấc mơ viết DQ, của ông:

For Don Quixote, more than any book ever

written, is literature. (1)

Độc giả TV chắc

còn nhớ, câu chuyện, 1 ông hổ, mê văn chương, và mê 1 văn nhân quá -

thí dụ GCC! - bèn hóa

thân làm người, và làm bạn với vị văn nhân, thực sự là làm thằng bồi,

để hàng ngày nghe văn chương.

Thế rồi, một bữa, ông chủ ghé 1 diễn đàn văn

học, Hạ Vệ, hay Da Mùi gì đó, và bọn này mở tiệc

đãi, thi nhau xổ thơ, văn.

Lúc

đầu thì ông hổ cố chịu, sau chịu không nổi, năn nỉ, thôi đi, tha cho

tôi.

Lũ

kia đâu chịu nghe, càng xổ tiếp.

Thế là ông hổ điên lên, lắc mình 1 phát, biến

thành hổ, quơ chân quạt chết hết, rồi cúi lạy vị văn nhân, bỏ đi!

Tàn Ngày

If Wilson

and Swift may be considered quintessentially English], then Kazuo

Ishiguro [and

Timothy Mo] offer evidence of how the English-language novel is now

enriched

from a diversity of cultures. The former is of Japanese extraction, the

latter

of Chinese, though both were educated in England. Ishiguro's three

novels - A

Pale View of Hills (1982), An Artist of the Floating World (1986) and

The

Remains of the Day (1989) - have all been distinguished by an

exquisite

precision; he is a writer who works scrupulously within self-imposed

limits,

achieving his effects by understatement and the adroit deployment of

his material.

Each of his novels has an unmistakable identity; yet he displays his

virtuosity

in his use of a different narrative voice in each. The Remains of the Day, for

instance, is narrated by an elderly English butler. In his portrayal of

this

character, so different from himself, Ishiguro shows himself a pure

novelist.

The central question which occupies Mr. Stevens, the narrator, is `what

makes a

great butler?'. This may seem an extraordinary question for a young

novelist to

pose at the end of the twentieth century; yet Ishiguro uses it in order

to be

able to ask the far more important question of how a man's life is

justified.

Graceful,

humorous, subtle and enquiring, Ishiguro is a writer who impresses by

his

willingness to submerge his own personality and by his fidelity to his

material. Each of his novels is thoroughly and perfectly composed; the

proportions are always seemly. They acquire a strength and authority

from

Ishiguro's acceptance of physical realities and from the exactness of

his

perceptions.

Allan Massie

Đoạn trên, GCC

trích từ 1 bài viết, nay không làm sao tìm lại được. Nhận xét thần sầu,

về 1

nhà văn mũi tẹt, viết bằng 1 thứ tiếng của tụi mũi lõ, mà tụi lõ chưa

từng vươn

tới tầm cỡ như vậy, thế mới khủng khiếp, thế mới ngả đầu bái phục.

Đâu có phải

cứ viết bằng tiếng của Tẩy mũi lõ, như mấy anh chị Mít, là thành nhà

văn đâu?

Trong

tất cả những thứ VC viết ra, rồi được thế giới gật gù, chỉ có 1 Nỗi

Buồn Chiến

Tranh

của Bảo Ninh.

Đau thế.

Cứ đeo kiếng

vô, là đọc được chữ - cứ viết bằng tiếng mũi lõ, là trở thành văn

chương - hồi nhỏ, đọc Quốc Văn Giáo Khoa Thư, phải đến già,

ra được

Xứ Người, Gấu mới hiểu ra ý nghĩa của ẩn dụ này.

Viết bằng tiếng nước Người, là

một cách biến kít thành vàng ròng!

Nhưng với lũ Bắc Kít, ở Paris, nếu là vàng ròng, thì vưỡn còn mùi chiến

lợi phẩm,

mùi tàn dư Mỹ Ngụy, trong có mùi kít Mẽo!

Lũ này, là cũng xuất phát từ sân nuôi gà vịt Hà Nội. Cái tay NG của đài

Bi Bì Xèo đã từng đi 1 đường về chúng.

Gấu cũng lầm về tay Khờ.

Như lầm về Sến.

Với Sến, là

hình ảnh 1 thiên sứ Mít!

Với bạn

quí… Khờ, là hình ảnh một anh chàng

Rhett Butler, đang đưa em Scarlett O'Hara di tản, nghe mất Miền Nam,

bèn đá cho

em 1 phát, trở về… nhà, tham dự cuộc

chiến,

dù chỉ hưởng tí xái, một, hai ngày, nhưng thà như vậy, suốt đời không

phải đau nỗi đau

đếch có mặt

ở Lò Thiêu, của… Steiner! Nhân vật Kiệt

của TTT, trong Một Chủ Nhật Khác, chẳng

là từ bạn quí Khờ của Gấu mà ra ư: Đang… lưu

vong, nghe mất quê hương, bèn trở về, nói

là do bà vợ đang có bầu, Thuỳ, kêu về, nhưng thực sự là do tiếng gọi

khủng khiếp

của 1 Miền Nam, "bớ người ta, kíu tui với"!

Hà, hà!

Note: Nhân

nhắc tới TTT, tới MCNK, bèn nhớ ra Bếp

Lửa, anh chàng Đại và cuốn Tội

Ác và Hình

Phạt của Dos, cuốn sách gối đầu giuờng trước khi bỏ ra ngoài ấy

- tức ra bưng,

lên rừng, theo VC - của anh ta. Cuốn này, được cả hai tờ Obs

và Time chọn, 1 trong

những tuyệt tác của nhân loại.

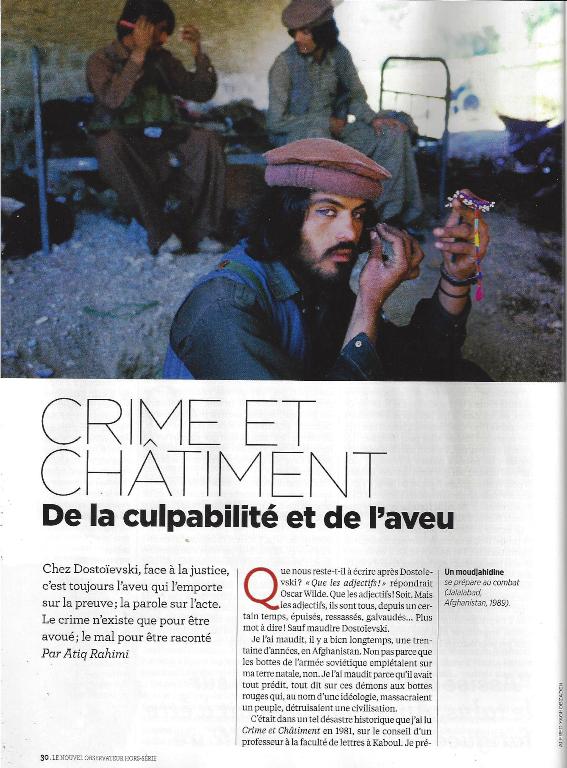

Tội Ác và

Hình Phạt

Ở Dos, trước

công lý, luôn luôn lời thú tội vượt chứng cớ, lời nói vượt hành

động. Tội

ác hiện hữu là để thú ra, cái ác, là để kể ra.

GCC tin rằng,

sau này, sẽ có 1 cuốn tiểu thuyết, của 1 tên VC Bắc Kít, thú tội, về

Tội Ác làm thịt Miền

Nam!

Phải là giả

tưởng mới OK.

Hiện thực chỉ là kít, thí

dụ, Đêm

giữa ban ngày, Bên thắng nhục.

Cũng thú tội đấy, nhưng đồ dởm không à!

Bằng lời dối

trá, ta nói ra sự thực, là vậy!

Hà, hà!

Atiq Rahimi

là tác giả Hòn Đá Nhẫn Nhục, Syngué sabour, Pierre de

Patience, giải

Goncourt 2008, đã chuyển thành phim. Ông

còn là tác giả cuốn Trời đánh ông đi, hỡi

Dos, Maudit soit Dos, 2011

Atiq Rahimi: "Écrire dans

une autre langue est un plaisir"

Viết bằng một ngôn ngữ khác là một niềm vui

Ông

mê Tây, mê Đầm từ thuở nào?

Vào năm 14 tuổi tôi khám phá ra Những người khốn khổ, của Hugo, qua

bản dịch tiếng Ba Tư. Tại Trung tâm văn hóa Tây, tôi khám phá ra

Đợt Sóng Mới, Jean-Luc Godard, Hisroshima tình tôi,

và những cuốn phim của Claude Sautet mà tôi thật mê ý nghĩa nhân bản ở

trong đó.

Ở

xứ Afghanistan CS đó mà cũng có thể tiếp cận văn hóa Tây sao?

Đúng như vậy, mặc dù khủng bố, mặc dù kiểm duyệt. Ở

chuyên khoa đại học, tôi trình bầy một đề tài về Camus, và được Thành

Đoàn hỏi thăm sức khoẻ, “Cấm không được nói về đám trí thức trưởng giả”.

Viết

văn bằng tiếng Tây,về nỗi đau và sự bất bình, nổi loạn, muốn “làm giặc”

của một đàn bà ngồi bên cái thân hình mê man bất động của người chồng,

một câu chuyện xẩy ra ở Afghanistan hay một nơi chốn nào đó…

-Có thể là do đề tài của cuốn truyện. Tiếng mẹ đẻ là

thứ tiếng người ta học sự cấm đoán, điều cấm kỵ. Để nói về một thể xác

người nữ, chắc chắn là phải sử dụng thứ ngôn ngữ thứ nhì, ngôn ngữ của

sự thừa nhận. Viết bằng tiếng Pháp cho phép tôi thực sự xâm nhập vào

bên trong những nhân vật, và nói về thân xác. Viết bằng một ngôn ngữ

khác thì là một niềm vui thích, giống như làm tình. (1)

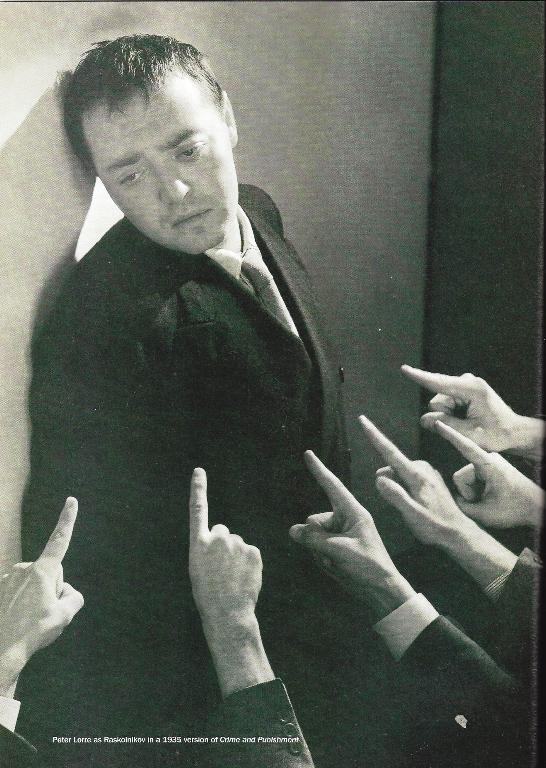

Rodion R. Raskolnikov

Origin:

Fyodor Dostoyevsky's 1866 novel, Crime

and Punishment

From Dante's

Inferno, where hell seems a good deal

more interesting than heaven, to Milton's Paradise

Lost, where Satan gets all the best lines, to Shakespeare's Othello, where

Iago's intrigues are more compelling than Othello's virtues, writers

have

learned fiction's dark secret: the allure of evil trumps the banality

of good.

Yet in Fyodor Dostoyevsky's Crime and

Punishment, the author passes rapidly over his main character's

evil deeds-the

pointless murders of an innocent old woman and her half-sister-to

explore their

psychological consequences.

Dostoyevsky understood punishment not as a

concept

but as bitterly lived experience. A parlor radical in his youth, he was

arrested, along with dozens of utopian associates who questioned the

regime of Czar

Nicholas I, and put through a mind-bending form of psychological

torture: he

was convicted of treason, sentenced to death, blindfolded and put in

front of a

firing squad-only to be given a reprieve at the last moment and

sentenced to

four years of exile in a Siberian prison camp.

The author's years in

chains

deepened and darkened his view of the human condition and inspired his

creation

of Raskolnikov, the impoverished former student whose love of

idealistic

concepts outpaces his love for the messy realities of human life and

leads him

to justify his murders as an expression of his self-declared

superiority over

the common man. In Raskolnikov, Dostoyevsky traced the chilling

trajectory of

the sort of evil that begins with grandiose visions of the superhuman,

only to

end in the death camps of Hitler's Germany, the gulag of Stalin's

Russia and

the horrors of the Great Cultural Revolution of Mao's China. The guilty

young

man is the dark prophet of the 20th century's false gods.

Time: The

100 most influential people who never lived, 100 người ảnh hưởng nhất

chưa hề sống.

Từ Hỏa Ngục

của Dante, nơi địa ngục xem ra

bảnh hơn nhiều so với thiên đường, tới Thiên

Đàng Đã Mất của Milton, nơi quỉ Satan được tác giả dành cho những

dòng thật

là tuyệt vời, tới Othello, nơi những

âu mưu của Iago mới thần sầu làm sao, so với thứ đạo hạnh hạng bét của

Othello,

những nhà văn biết, học được, cái bí ẩn đen tối của giả tưởng: cái dáng

dấp của

cái ác phong nhã, đánh bại cái tầm phào, cù lần của cái tốt, và hơn thế

nữa: nó

là hồi chuông báo tử của cái thiện!

Tuy nhiên,

trong Tội Ác và Hình Phạt của Dos,

tác giả đi 1 đường thoáng qua, về tội ác, và dành cả cuốn sách của mình

để khai

triển hậu quả của nó.

Ông biết về

hình phạt không phải như khái niệm mà là 1 kinh nghiệm cay đắng đã từng

trải

qua….

Bà cảm thấy thế nào khi sống

tại nước Pháp

hiện nay?

Tôi gần như luôn luôn cảm thấy

mình sống

trong tình trạng lưu vong. Tôi tin rằng mặc dù sống ở Pháp đã lâu vậy

mà tôi

chưa bao giờ nói: đây là xứ sở của tôi. Nhưng tôi cũng không nói Việt Nam là

xứ sở của

tôi. Tôi coi tiếng Pháp là tình yêu sâu đậm của mình. Đó là cái neo độc

nhất

cắm vào thực tại mà tôi luôn thấy, thật hung bạo, Tôi rất lo ngại về sự

bùng

phát của một thứ chủ nghĩa quốc gia dữ dằn ở Âu Châu. Tôi có cảm tưởng

Âu Châu

ngày càng trở nên lạnh nhạt, và càng ngày càng bớt bao dung. Có lẽ

chúng ta

đang ở trong một thời hòa bình chỉ ở ngoài mặt, có vẻ như hòa bình,

những cuộc

xung đột ngầm chỉ chờ dịp để bùng nổ, tôi sống trong sợ hãi một cú bộc

phát

lớn.

Trong Cronos, bà đưa ra một lời

kêu gọi,

về một sự phản kháng. Phản kháng như thế nào, theo một hình thức nào,

vào lúc

này, theo bà?

Đó là thứ tình cảm bực tức,

muốn làm một

cái gì đó, muốn nổi loạn, khi tôi theo dõi những biến động, Đôi khi tôi

cảm

thấy gần như ở trong tình trạng bị chúng trấn áp đến nghẹt thở. Tới mức

có lúc

tôi ngưng không đọc báo hàng ngày, không nghe tin tức trên đài nữa. Như

nữ nhân

vật Cronos, tôi thỉnh thoảng ở trong tình trạng cảm thấy mình bị cự

tuyệt, bị

sự chối từ cám dỗ…. Như nữ nhân vật này, tôi chỉ có thể chiến đấu bằng

ngòi bút.

Có thể 1 ngày nào đó những biến động bắt buộc tôi phải hành động khác

đi. Nhưng

vào lúc này, trong xã hội mà tôi sống trong đó, khí giới độc nhất của

tôi là viết.

Dù có thể chẳng được hồi đáp

Tôi luôn viết với thứ tình cảm

là tôi có

thể giảng đạo ở giữa sa mạc. Nhưng điều đó không đánh gục tôi. Ngược

lại. Một cách

nào đó, vậy mà lại hay. Đừng bao giờ cảm thấy mình viết ra là được chấp

nhận. Nếu

không bạn sẽ bị ru ngủ bởi sự hài lòng, thoải mái. Bằng mọi cách, cố mà

đừng để

xẩy ra tình trạng tự hoang phế, hay thương thân trách phận. Tình cảm

hài lòng,

và oán hận là hai tảng đá ngầm lớn mà tôi cố gắng tránh né.

Những cuốn sách của bà hay nói tới đề tài

bị bỏ bùa…

Đề tài này luôn ám ảnh tôi. Nó

đầy rẫy ở

trong những tiểu thuyết của Henry James, trong có những phụ nữ bị mồi

chài bởi

những tên sở khanh. Văn chương tuyệt vời nhất là khi nó mê hoặc, quyến

rũ. Tôi

mê những nhân vật giống như là một cái mồi, sẵn sàng phơi mình ra để mà

được… làm

thịt. Bản thân tôi, cũng đã từng bị mê hoặc, hết còn chủ động

được,

trước một vài

người, trong đời tôi, và tôi luôn quan tâm tới điều này.

*

Đây là

đề tài ‘ban phát’, thay vì ‘giải phóng’ bà 'Thấm

Vân Thấm Dần Thấm Tới Đất' [mô phỏng cái tít “Mưa không ướt đất” của 1

nữ văn sĩ

nổi tiếng trước 1975 ở Miền Nam] từng đề cập.

Và một

trong những tiểu thuyết thần sầu của Henry James mà Linda Lê nhắc tới

ở đây, là Washington

Square.

Cuốn này đã

được quay thành phim, với nhân

vật thần sầu, Monty Cliff, đóng vai anh chàng sở khanh đào mỏ.

Nhân

trong

nước đang ì xèo về phim Cánh Đồng

Bất Tận chuyển thể từ tiểu thuyết của

Nguyễn

Ngọc Tư, TV bèn ‘lệch pha’qua nhân vật đàng điếm sở khanh Monty Cliff,

một trong

những kép độc được mấy em gái thời Gấu mới lớn mê mẩn, không chỉ anh

ta, mà còn, nào là Elvis

Presley,

Gregory Peck, Clark Gable...

Tên nào

Gấu cũng thù, do hồi đó Gấu

mê một

em, và

thần tượng của em là những đấng trên!

Gấu Cái

cũng cực mê Elvis Presley, từng trốn học đi coi phim có anh ta

thủ vai chính! (1)

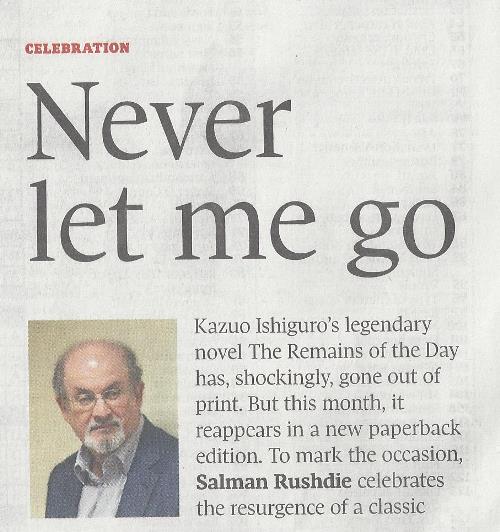

Cuốn tiểu

thuyết truyền kỳ “Tàn Ngày” của Kazuo Ishiguoro, quái làm sao, ở cái xứ

Tây

Phương, vậy mà tuyệt bản. Nhưng tháng này, nó tái xuất hiện trên chốn

giang hồ,

và Salman Rushdie bèn đi 1 đường chào mừng.

Trong “Quê Hương Tưởng

Tượng”, ông

đã viết về nó.

Lạ là, “Tàn

Ngày” là cuốn tiểu thuyết, bản dịch tiếng Anh, đầu tiên, Gấu đọc, khi

ra được hải

ngoại, nghĩa là tới được xứ xở thứ ba, là Canada, quê hương thứ nhì của

GCC.

UNHCR có thuật

ngữ, Đệ Nhất, Đệ Nhị và Đệ Tam Quốc Gia, để chỉ cuộc đời 1 tên tị nạn.

Đệ Nhất,

là quê hương mà nó phải bỏ chạy, Đệ Nhị là xứ tạm dung, chờ Đệ Tam

nhận, cho tái

định cư.

Khi viết cho

talawas, bài đầu tiên làm quen, "Dịch là cướp", GCC chỉ nghĩ theo

chiều, dịch từ

tiếng Anh của tiếng Việt. Không hề nghĩ đến chiều dịch từ tiếng “da

màu” qua tiếng

Anh.

Trong nước gọi là giới thiệu dòng văn chương Mít, với thế giới.

"Tàn Ngày", không phải như vậy, theo nghĩa, chính cái xứ sở nói tiếng

Anh cần nó. Trong

tiếng Anh, có cái gì thiếu, và chính "Tàn Ngày" mang lại cho nó.

Khủng đến mức như

thế.

Trong khi đám

Mít ở Tây viết tiếng Tây, theo Gấu, chỉ làm dơ, làm bửn, làm nhục tiếng

Tây!

Đó là sự thực.

Không tin, bạn cứ thử đọc lũ này, là thấy rõ.

TV sẽ giới

thiệu cả hai bài viết của Salman Rushdie.

The man who

wrote The Remains of the Day in

the pitch-perfect voice of an English butler is

himself very polite. After greeting me at the door of his home in

London’s

Golders Green, he immediately offered to make me tea, though to judge

from his

lack of assurance over the choice in his cupboard he is not a regular

four P.M.

Assam drinker. When I arrived for our second visit, the tea things were

already

laid out in the informal den. He patiently began recounting the details

of his

life, always with an amused tolerance for his younger self, especially

the

guitar-playing hippie who wrote his college essays using disembodied

phrases

separated by full stops. “This was encouraged by professors,” he

recalled.

“Apart from one very conservative lecturer from Africa. But he was very

polite.

He would say, Mr. Ishiguro, there is a problem about your style. If you

reproduced this on the examination, I would have to give you a

less-than-satisfactory grade.”

Đoạn mở ra

cuộc nói chuyện, và sau đó, là bài phỏng vấn, trên đây, của tờ The

Paris

Review, là đã khiến chúng ta tò mò rồi, “Mr. Ishiguro, có một vấn đề

trong văn

phong của ông”.

Liệu có tên

Tẩy chính gốc nào, tìm ra “vấn đề trong văn phong, biết bằng tiếng Tẩy”

của lũ

Mít, chọn Paris làm nhà của chúng?

Một trong những

tác giả hải ngoại đầu tiên mà Gấu đọc, và tò mò về văn phong là Đỗ KH,

khi đọc

“Cây Gậy Làm Mưa” của anh. Gấu đã viết về vụ này, liền sau đó, trong

bài viết về

ông anh nhà thơ:

Bao nhiêu

năm nhìn lại, tôi nhìn ra thất bại của bản thân, khi tìm cách thay đổi

văn mạch

cũ của văn chương Việt Nam. Sự thất bại không phải vì dòng văn chương

mới mẻ đó

không thích hợp với quan niệm thưởng ngoạn của đa số độc giả, mà là:

Tôi quá bị

ám ảnh bởi vấn đề kỹ thuật. Một cách nào đó, tôi đã không lãnh hội được

bài học

của Kafka, khi ông cho rằng, kỹ thuật chính là hữu thể (être) của văn

chương.

Rõ ràng, câu văn bị kỹ thuật non nớt, sự vụng về, tham vọng làm mới văn

chương... tàn phá, trở thành vụn nát.

Nhưng lối viết đó không phải là

một thất

bại. Theo tôi, trong cuốn "Cây gậy làm mưa", Đỗ KH. cũng đã thử nghiệm

một lối viết mới "na ná" như vậy, và hơn thế nữa, tác giả đưa luôn

những

mạch văn "ngoại lai", những ngôn ngữ " quốc tế"... vào

trong văn mạch Việt Nam. (1)

Tay này, Đỗ KH, Đỗ Khiêm, sau

này, hỏng, cực hỏng. Thất bại, trong toan tính làm mới tiếng Mít, có

thể, anh

quay qua viết văn bằng tiếng Tẩy, 1 thứ “ký, kiếc”, gì đó, cực nhảm,

theo Gấu.

Cũng 1 thứ lạc

loài, tuy không ở Paris!

[Sẽ viết rõ ra thêm, sau, sau khi giới thiệu

cách viết

của Naipaul. NQT]

V/v Đỗ KH.

Gấu nhớ đọc trên net, có 1

tay nào đó, hỏi Lê Đạt, về thơ hải ngoại, và nhắc tới

thơ Đỗ Kh. Lê Đạt phán, nhớ đại khái, tay này mà thơ cái con

khỉ gì - ngôn

ngữ của GCC - một tay viết "ký", đúng hơn.

Nhận xét cùa Lê Đạt đúng chỉ có 1 nửa, như 1 nửa... sự thực.

Thơ Đỗ Kh, nếu hỏng, là

hỏng theo nghĩa chung của thơ Mít, một thứ thơ

kể lể, cũng 1 cách "tự sự", narative, hay được đám hải ngoại sử dụng,

khi ngồi

bên ly cà phê, nhớ bạn quí...

Thơ Raymond Carver cũng bị

1 số

đấng phê

bình coi thuộc dạng này, nhưng không đúng. Bởi là vì toàn thể 1 bài thơ

của Raymond

Carver, sau những dòng kể lể, thể nào cũng toát ra 1 cái gì đó, mắc mớ

đến nỗi

sầu đời của ông.

Hoặc 1 đốn ngộ về kiếp người.

Theo GCC, 1 trong những

người đọc ra thơ của RC, là

Czeslaw Milosz.

Nhưng ký của Đỗ Kh mới cực

hỏng. Cái hỏng của nó, theo GCC, là do trước

đó, ký

của Mít, hỏng, theo chiều thuận, thí dụ, thì bây giờ, hỏng, theo chiều

ngược hẳn

lại.

Trước, ký, tiểu thuyết, truyện ngắn, bất cứ cái đéo gì viết ra, là

phải nhắm

tới Đạo Lớn của… VC.

Sau đó, ngược hẳn

lại,

chỉ nói tới cái tôi, 1 cái tôi đầy sex, đầy trụy lạc, đầy hưởng thụ,

đầy nhơ bửn. (1)

NQT

Thơ RC rất đỗi thê lương,

và nỗi cô đơn đến với chúng ta, rất đỗi bất ngờ. Trong thơ ông có nỗi

buồn cháy da cháy thịt, nhưng không phải là do mất 1 người thân, thí dụ

như bài sau đây, GCC thật mê.

Chiều tối

Tôi câu cá 1 mình

vào buổi chiều tối mùa thu tiều tụy đó,

Màn đêm cứ thế mò ra.

Cảm thấy,

mất mát ơi là mất mát

và rồi,

vui ơi là vui,

khi tóm được một chú cá hồi bạc,

mời chú lên thuyền

nhúng 1 cái lưới bên dưới chú.

Trái tim bí mật!

Khi tôi nhìn xuống làn nước xao động,

nhìn lên đường viền đen đen của rặng núi

phiá sau thành phố,

chẳng thấy gợi lên một điều gì,

và rồi

tôi mới đau đớn làm sao,

giả như sự chờ mong dài này,

lại trở lại một lần nữa,

trước khi tôi chết.

Xa cách mọi chuyện.

L'AUTRE VIE

Et maintenant l'autre vie.

Celle où

on ne fera pas d'erreurs.

Lou

LIPSITZ.

Cõi Khác

Nào, bây giờ là cõi khác

Cõi đếch có lầm lẫn

Tàn Ngày tuyệt

bản, được tái bản, Rushdie đi 1 đường chào mừng, trên tờ báo ngày Globe

and

Mail, trích từ lời giới thiệu của R. nhân cuốn sách tái xuất

hiện trên

chốn

giang hồ, một tác phẩm cổ điển

Cuốn này GCC

đã từng giới thiệu, ngay từ ngày mới ra hải ngoại, trên 1 đài TV của

Toronto,

trong 1 chương trình chừng 15 phút của Mít.

Tếu thế.

Nói chuyện

cam chịu lịch sử, và nổi tiếng nhờ nó, bảnh nhất, theo Gấu, là nhà văn

Anh gốc

Nhật, viết văn bằng tiếng Anh 'hách hơn Ăng lê', Kazuo Ishiguro, tác

giả “Tàn

Ngày”, được Booker Prize. Ông thuộc trào lưu những nhà văn trẻ bảnh của

Anh, gồm

Martin Amis, Salman Rushdie… Trên số báo Le Magazine Littéraire, April

2006, đặc biệt về 'em' Duras, cô đầm ở xứ An Nam Mít, có bài phỏng vần

ông, do

Trần Minh Huy thực hiện, ‘K.I., thời của hoài nhớ’, ‘K.I, chúng ta là

những đứa

trẻ mồ côi’...

Khi được hỏi,

sự thiếu vắng nổi loạn thật là rõ ràng trong tất cả các tác phẩm của

ông, K.I.

trả lời: "Đúng như thế, những nhân

vật như Stevens trong Tàn Ngày, họ chấp nhận những gì đời đem đến cho

họ, và, bằng

mọi cách, đóng trọn vai trò cam chịu lịch sử, thay vì nổi loạn, bỏ

chạy… và cố

tìm trong đó, cái gọi là nhân phẩm, chẳng bao giờ tra hỏi chế độ."

Cái gọi là

nhân phẩm, bật ra từ Tàn Ngày, và là

chủ đề của cuốn tiểu thuyết đưa ông đài danh vọng, và đã được quay

thành phim…

"Tôi [K.I. muốn chứng minh sự can đảm của Stevens, nhân phẩm của anh

ta,

khi đối mặt với cái điều, là, người ta đã làm hỏng đời của anh ta”.

Rushdie đọc Tàn Ngày, khác, cái sự thất bại lớn lao

nhất của Stevens, là hậu quả của niềm tin sâu thẳm của ông ta - rằng

chủ của

ông, sư phụ của ông, his master, làm việc cho điều tốt của nhân loại.

Đọc,

“lệch

pha” đi, thì nó ra cái thất bại lớn lao nhất của xứ Mít:

Chúng cứ nghĩ đất nước,

độc lập thống nhất, qui về 1 mối, là số 1, là tốt nhất cho… Mít!

Celebration

Never Let Me Go

I was very

consciously trying to write for an international audience," Kazuo

Ishiguro

says of “The Remains of the Day” in his Paris Review interview. "One of

the ways I thought I could do this was to take a myth of England that

was known

internationally - in this case, the English butler."

"Jeeves

was a big influence." This is a necessary genuflection. No literary

butler

can ever quite escape the gravitational field of Wodehouse's shimmering

Reginald, gentleman's gentleman par excellence, savior, so often, of

Bertie Wooster's

imperiled bacon. But, even in the Wodehousian canon, Jeeves does not

stand

alone. Behind him can be seen the rather more louche figure of the Earl

of

Emsworth's man, Sebastian Beach, enjoying a quiet tipple in the

butler's pantry

at Blandings Castle. And other butlers - Meadowes, Maple, Mulready,

Purvis -

float in and out of Wodehouse's world, not all of them pillars of

probity. The

English butler, the shadow that speaks, is, like all good myths,

multiple and contradictory.

One can't help feeling that Gordon Jackson's portrayal of the stoic

Hudson in

the 1970S TV series Upstairs, Downstairs

may have been as important to

Ishiguro as Jeeves: the butler as liminal figure, standing on the

border

between the worlds of "Upstairs" and "Downstairs,"

"Mr. Hudson" to the servants, plain "Hudson" to the gilded

creatures he serves.

Now that the

popularity of another television series, Downton Abbey, has introduced

a new

generation to the bizarreries of the English class system, Ishiguro's

powerful,

understated entry into that lost time to make, as he says, a portrait

of a

"wasted life," provides a salutary, disenchanted counterpoint to the

less sceptical methods of Julian Fellowes's TV drama. The

Remains of the Day, in its quiet, almost stealthy way,

demolishes the value system of the whole upstairs-downstairs

world.

(It should

be said that Ishiguro's butler is in his way as complete a fiction as

Jeeves.

Just as Wodehouse made immortal a world that never existed except in

his

imagination, so also Ishiguro projects his imagination into a poorly

documented

zone. "I was surprised to find," he says, "how little there was

about servants written by servants, given that a sizable proportion of

people

in this country were employed in service right up until the Second

World War.

It was amazing that so few of them had thought their lives worth

writing about.

So most of the stuff in The Remains of the

Day ... was made up.")

The surface of

The Remains of the Day is almost perfectly still. Stevens, a butler

well past

his prime, is on a week's motoring holiday in the West Country. He

tootles

around, taking in the sights and encountering a series of

green-and-pleasant

country folk who seem to have escaped from one of those English films

of the

1950s in which the lower orders doff their caps and behave with respect

towards

a gent with properly creased trousers and flattened vowels. It is, in

fact,

July 1956 -the month in which Nasser's nationalization of the Suez

Canal

triggered the Suez Crisis - but such contemporaneities barely impinge

upon the

text. (Ishiguro's first novel, A Pale View

of Hills, was set in post-war Nagasaki but hardly mentioned the

Bomb. The

Remains of the Day ignores Suez, even though that debacle marked the

end of the

kind of Britain whose passing is a central subject of the novel.)

Nothing much

happens. The high point of Mr. Stevens's little outing is his visit to

Miss

Kenton, the former housekeeper at Darlington Hall, the great house to

which

Stevens is still attached as "part of the package," even though

ownership has passed from Lord Darlington to a jovial American named

Farraday

who has a disconcerting tendency to banter. Stevens

hopes to persuade Miss Kenton to return to the Hall. His hopes come to

nothing.

He makes his way home. Tiny events; but why, then, is the aging

manservant to

be found, near the end of his holiday, weeping before a complete

stranger on

the pier at Weymouth? Why, when the stranger tells him that he ought to

put his

feet up and enjoy the evening of his life, is it so hard for Stevens to

accept

such sensible, if banal, advice? What has blighted the remains of his

day?

Just below

the understatement of the novel's. surface is a turbulence as immense

as it is

slow; for The Remains of the Day is in fact a brilliant subversion of

the

fictional modes from which it seems at first to descend. Death, change,

pain

and evil invade the innocent Wodehouse world. (In Wodehouse, even the

Oswald

Mosley-like Roderick Spade of the Black Shorts movement, as close to an

evil

character as that author ever created, is rendered comically pathetic

by

"swanking about," as Bertie says, "in footer bags.") The

time-hallowed bonds between master and servant, and the codes by which

both

live, are no longer dependable absolutes but rather sources of ruinous

self-deceptions; even the happy yokels Stevens meets on his travels

turn out to

stand for the post-war values of democracy and individual and

collective rights

which have turned Stevens and his kind into tragicomic anachronisms.

"You can't

have dignity if you're a slave," the butler is informed in a Devon

cottage, but for Stevens, dignity has always meant the subjugation of

the self

to the job, and of his destiny to his master's. What then is our true

relationship to power? Are we its servants or its possessors? It is the

rare

achievement of Ishiguro's novel to pose Big Questions - What is

Englishness?

What is greatness? What is dignity? - with a delicacy and humor that do

not

obscure the tough-mindedness beneath. The real story here is that of a

man destroyed

by the ideas upon which he has built his life. Stevens is much

preoccupied by "greatness,"

which, for him, means something very like restraint. The greatness of

the British

landscape lies, he believes, in its lack of the "unseemly

demonstrativeness"

of African and American scenery. It was his father, also a butler, who

epitomized this idea of greatness; yet it was just this notion which

stood

between father and son, breeding deep resentments and an inarticulacy

of the

emotions that destroyed their love. In Stevens's view, greatness in a

butler

"has to do crucially with the butler's ability not to abandon the

professional being he inhabits." This is linked to Englishness.

Continentals and Celts do not make good butlers because of their

tendency to

"run about screaming" at the slightest provocation. Yet it is

Stevens's longing for this kind of "greatness" that has wrecked his

one chance of finding romantic love. Hiding within his role, he long

ago drove

Miss Kenton away into the arms of another man. "Why, why, why do you

always have to pretend?" she asks him in despair, revealing his

greatness

to be a mask, a cowardice, a lie. Stevens's greatest defeat is the

consequence

of his most profound conviction - that his master is working for the

good of

humanity, and that his own glory lies in serving him. But Lord

Darlington is,

and is finally dis- graced as, a Nazi collaborator and dupe. Ste- vens,

a

cut-price St. Peter, denies him at least twice, but feels forever

tainted by

his master's fall. Darlington, like Stevens, is destroyed by a personal

code of

ethics. His disapproval of the ungentlemanly harshness towards the

Germans of

the Treaty of Versailles is what -propels him towards his

collaborationist

doom. Ideals, Ishiguro shows us, can corrupt thoroughly as cynicism.

The film

version of The Remains of the Day

softens the book's portrait of Lord

Darlington. Sympathetically portrayed with a stiff-up lip aplomb that

slowly

disintegrates, he comes across as more of a fool than a more to be

pitied than

censured, Ishiguro’s novel is less equivocal, its portrait of the

British

aristocracy's flirtation with Nazism untinged by sentiment. In this

matter

Stevens is an unreliable narrator, making excuses for his lordship -

"Lord

Darlington wasn't a bad man. He wasn't a bad man at all" - but the

reader

is allowed to see more clearly than the butler, and can't make any such

excuse,

At least Lord Darlington chose his own path. "I cannot even claim

that," Stevens mourns. "You see, I trusted ... I can't even say I

made my own mistakes. Really -one has to ask oneself - what dignity is

there in

that?" His whole life has been a foolish mistake, and his only defence

against the horror of this knowledge is the same capacity for self-

deception

which proved his undoing. It's a cruel and beautiful conclusion to a

story both

beautiful and cruel.

With The

Remains of the Day, Ishiguro turned away from the Japanese

settings of his

first two novels and revealed that his sensibility was not rooted in

anyone

place, but capable of travel and metamorphosis. "By the time I started The

Remains of the Day," he told the Paris Review, " I realized that

the

essence of what I wanted to write was movable ... For me, the essence

doesn't

lie in the setting." Where, then, might that essence lie? "Without

psychoanalyzing myself. I can't say why. You should

never believe an author if he tells you why he has certain recurring

themes."

Copyright ©

2014 Salman Rushdie. Excerpted from the foreword by Salman Rushdie to The

Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro. Published by Vintage

Canada, a

division

of Random House of Canada Limited, a Penguin Random House Company.

Reproduced

by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Kazuo

Ishiguro, The Art of Fiction

KAZDO

ISHIGDRO

The surface

of Kazuo Ishiguro's novel, The Remains of

the Day, is almost perfectly still. Stevens, a butler well past his

prime,

is on a week's motoring holiday in the West Country. He tootles around,

taking

in the sights and encountering a series of green-and-pleasant country

folk who

seem to have escaped from one of those English films of the 1950s in

which the

lower orders doff their caps and behave with respect towards a gent

with

properly creased trousers and flattened vowels. It is, in fact, July

1956; but

other, timeless worlds, the world of Jeeves and Bertie Wooster, the

upstairs-

downstairs world of Hudson, Mrs Bridges and the Bellamys, are also in

the air.

Nothing much happens. The high point of Mr

Stevens's little outing is his visit

to Miss Kenton, the former housekeeper at Darlington Hall, the great

house to

which Stevens is still attached as 'part of the package', even though

ownership

has passed from Lord Darlington to a jovial American named Farraday who

has a

disconcerting tendency to banter. Stevens hopes to persuade Miss Kenton

to

return to the Hall. His hopes come to nothing. He makes his way home.

Tiny

events; but why, then, is the ageing manservant to be found, near the

end of

his holiday, weeping before a complete stranger on the pier at

Weymouth? Why,

when the stranger tells him that he ought to put his feet up and enjoy

the

evening of his life, is it so hard for Stevens to accept such sensible,

if

banal, advice? What has blighted the remains of his day?

Just below the understatement

of the novel's surface is a turbulence as immense as it is slow; for The

Remains of the Day is in fact a brilliant subversion of the

fictional modes

from which it at first seems to descend. Death, change, pain and evil

invade

the Wodehouse-world; the time-hallowed bonds between master and

servant, and

the codes by .which both live, are no longer dependable absolutes but

rather

sources of ruinous self-deceptions; even the gallery of happy yokels

turns out

to stand for the post-war values of democracy and individual and

collective

rights which have turned Stevens and his kind into tragicomic

anachronisms.

'You can't have dignity if you're a slave,' the butler is informed in a

Devon

cottage; but for Stevens, dignity has always meant the subjugation of

the self

to the job, and of his destiny to his master's. What then is our true

relationship to power? Are we its servants or its possessors? It is the

rare

achievement of Ishiguro's novel to pose Big Questions (What is

Englishness?

What is greatness? What is dignity?) with a delicacy and humor that do

not

obscure the tough-mindedness beneath.

The real story here is that of a man

destroyed by the ideas upon which he has built his life. Stevens is

much

preoccupied by 'greatness', which, for him, means something very like

restraint. (The greatness of the British landscape lies, he believes,

in its

lack of the 'unseemly demonstrativeness' of African and American

scenery.) It

was his father, also a butler, who epitomized this idea of greatness;

yet it

was just this notion which stood between father and son, breeding deep

resentments and an inarticulacy of the emotions that destroyed their

love.

In

Stevens's view, greatness in a butler 'has to do crucially with the

butler's

ability not to abandon the professional being he inhabits.' This is

linked to

Englishness: Continentals and Celts do not make good butlers because of

their

tendency to 'run about screaming' at the slightest provocation. Yet it

is

Stevens's longing for such 'greatness' that wrecked his one chance of

finding

romantic love; hiding within his role, he long ago drove Miss Kenton

away, into

the arms of another man. 'Why, why, why do you always have to pretend?' she

asked in despair. His greatness is revealed as a mask, a cowardice, a

lie.

His

greatest defeat was brought about by his most profound conviction-that

his

master was working for the good of humanity, and that his own glory lay

in

serving him. But Lord Darlington ended his days in disgrace as a Nazi

collaborator and dupe; Stevens, a cut-price St Peter, denied him at

least

twice, but felt for ever tainted by his master's fall. Darlington, like

Stevens, was destroyed by his own code of ethics; his disapproval of

the

ungentlemanly harshness of the Treaty of Versailles is what led him

towards his

collaborationist doom. Ideals can corrupt as thoroughly as cynicism.

But at

least Lord Darlington chose his own path. 'I cannot even claim that,'

Stevens

mourns. 'You see, I trusted ... I can't even say I made my own

mistakes.

Really, one has to ask oneself, what dignity is there in that?' His

whole life

has been a foolish mistake; his only defence against the horror of this

knowledge is that same facility for self-deception which proved his

undoing.

It's a cruel and beautiful conclusion to a story both beautiful and

cruel.

Ishiguro's first novel, A Pale View of Hills, was set in

post- war Nagasaki but

never mentioned the Bomb; his new book is set in the very month that

Nasser

nationalized the Suez Canal, but fails to mention the crisis, even

though the Suez

debacle marked the end of a certain kind of Britain whose passing is a

subject

of the novel. Ishiguro's second 'Japanese' novel, An Artist of the Floating

World, also dealt with themes of collaboration, self-deception,

self-betrayal

and with certain notions of

formality and dignity that recur here. It seems that England and Japan

may not

be so very unlike one another, beneath their rather differently

inscrutable

surfaces.

1989

Salman

Rushdie

|

|