|

|

|

Mít vs Lò

Thiêu

Note: Bài viết của Bass, theo GCC, tuyệt.

Nhưng, vì ông không phải là Mít,

và hơn thế nữa, càng không phải 1 tên Bắc Kít, cho nên

ông không thể đẩy nó đến tận cùng, bật ra hai chân lý khổng

lồ về xứ Mít.

Thứ nhất, dân Bắc không hiểu dân chủ

nghĩa là gì, do họ chưa từng biết đến nó. Suốt bốn ngàn

năm dựng nước, hết phong kiến thì nô lệ Tầu, rồi một trăm năm nô lệ thằng Tây, chúng cũng đếch cho

biết mùi dân chủ, mà thay vì vậy, là bảo hộ, với đám cường hào

ác bá dựa oai Tẩy ị lên đầu nhân dân, thi nhau tác quái. Lũ

VC bây giờ, là kế thừa truyền thống đó.

Và chân lý khổng lồ

thứ nhì, ở cái nền của chế độ công an trị, là Cái Ác Bắc Kít.

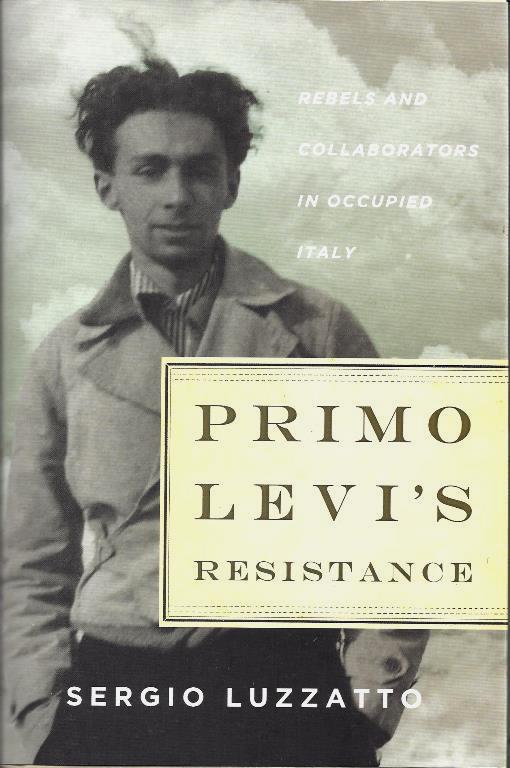

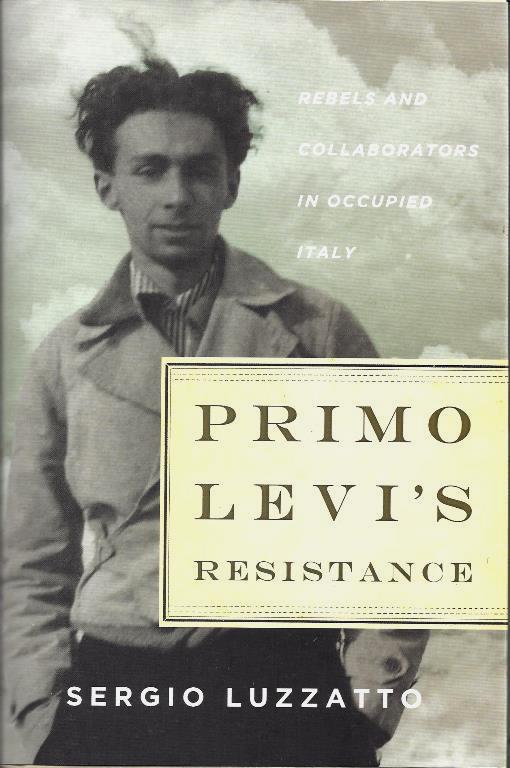

Nguyên tác tiếng Ý 2013.

Bản tiếng Anh, mới ra lò 2016

Nguyên tác tiếng Ý 2013.

Bản tiếng Anh, mới ra lò 2016.

A PIONEERING EXAMINATION OF THE ITALIAN

RESISTANCE

AND THE GRIM SECRET THAT HAUNTED PRIMO

LEVI'S LIFE

No

other Auschwitz survivor has been as literarily powerful and historically

influential as Primo Levi. Yet Levi was not only a victim or a witness.

In the fall of 1943, at the very start of the Italian Resistance, he was

a fighter, participating in the first attempts to launch guerrilla warfare

against occupying Nazi forces. Those three months have been largely overlooked

by Levi's biographers; indeed, they went strikingly unmentioned by Levi

himself. For the rest of his life he barely acknowledged that autumn

in the Alps. But an obscure passage in Levi's The Periodic Table

hints that his deportation to Auschwitz was linked directly to an incident

from that time: "an ugly secret" that had made him give up the struggle,

"extinguishing all will to resist, even to live."

What did Levi -mean by those dramatic lines? His small partisan

band, it appears, had turned on itself, committing a brutal act against

two of its own members. Using that shocking episode as a starting point,

Sergio Luzzatto offers a rich examination of the early days of the

Resistance, when the nascent movement struggled to define its role. Combining

investigative flair with profound empathy, he traces vivid portraits

of both rebels and Nazi collaborators, showing how their fates continued

to be intertwined into the postwar years. And he provides startling

insight into the origins of the moral complexity that runs through the

work of Primo Levi himself.

Lời giới thiệu trang bìa [jacket]

What enemy? Every man's his own

foe,

Each one split by his own

frontier,

Left hand enemy of the right.

Stand up, old enemies of

yourselves,

This war of ours is never

done.

One cannot read that last verse without

thinking of the moment in The Truce when Levi, having just left Auschwitz,

hears words of warning from another of the saved: guerra è sempre,

"war is always." The poem, written almost forty years later, is equally

eloquent and emphatic: the enemy is not outside, but inside the band

of comrades-indeed, inside each one of them. "Every man's his own foe,

/ Each one split by his own frontier."

It would be reassuring to think that in war the enemy

is always outside, and that once the enemy is defeated the problem

of wrongdoing has been resolved. On close inspection, however, the Italian

civil war (where it doesn't seem difficult, at least in retrospect, to

distinguish the side of rights and humanity from the side of inhumanity

and abuse) tells another story. It is a story of unquestionable good,

the fight against Nazi Fascism, intermixed with a story of profound wrong,

a wrong no human being, not even the best, can say he is totally free

of. Between black and white lie many shades of gray. At times this story

is one of simple, sharp contrasts. More often, its truths are expressed

in gradations.

Prologue

Còn lại

một việc nữa: văn chương miền Nam đâu có dừng lại ở năm 1975.

Đây mới là điều huyền bí nhất.

Blog

NL

Nếu như thế, thì cuộc chiến

cũng không chấm dứt với ngày đó.

Trong lời Prologue, trích

đoạn, trên, cho thấy, Primo Levi cũng không tin cuộc chiến Nazi chấm

dứt với cú Đồng Minh giải phóng nước Ý của ông.

War is always.

Cái trò bầu bán Đại Hụi Bịp vừa

xẩy ra mà không mặt dầy, trơ trẽn ư?

Chỉ cần 1 tên Bắc Kít, có tí tiếng tăm, thí dụ như 1 tên Nobel

Toán, viết trên FB, tao nói, đéo được, là sẽ có phản ứng.

Một người thôi ư? Đúng như thế. Một ông Solz đã từng làm. Một ông

Brodsky cũng đã từng.

Cái vụ anh y tá dạo bị Bắc Kít đá đít, thì cũng đã xẩy ra rồi,

với tên Hồ Tôn Hiến, Sáu Dân cái con mẹ gì đó.

Hình như bị đá đít rồi mà còn lăm le làm chuyện ruồi bu, thế là

chúng thịt luôn.

Bạn đọc TV có thể vặc Gấu, nè, nếu mi viết như thế, thì trường

hợp DTH, sao?

Căng, nhể!

Trọng Lú dưới cái nhìn của Người

Kinh Tế qua Đại Hụi Bịp: Trò

ma nớp của loài bò sát

Chính trị xứ Mít

VC

Politics in Vietnam

Reptilian manoeuvres

Trò ma nớp của loài bò sát

A colourful prime minister goes, as the grey men stay

Một vì thủ tướng màu mè ra đi, một lũ muối tiêu ở lại

Note:

Bảnh thật, đám lề trái cũng không nghĩ ra nổi, hình ảnh 1 lũ bò sát ở

Đại Hội Bịp, và cái chết của vị đại cha già dân tộc, là con rùa vàng, biểu

tượng của bốn ngàn năm

văn minh Sông Hồng, nằm chết lều bều trên mặt Hồ Gươm!

Carry on, Nguyen Phu TrongWHEN Great Grandfather,

a revered turtle which had long paddled around Hanoi’s central lake, was

found dead on the eve of the Communist Party’s five-yearly congress, many

Vietnamese thought it a bad omen for the ruling party. The animal embodied

a legend about a 15th-century Vietnamese warrior who presented his sword

to a turtle after vanquishing the Chinese. Some wondered whether the party’s

leaders, whose dusty Marxism-Leninism feels increasingly out of step with

Vietnam’s youthful population of 93m, were also losing their edge.

As it happens, the

congress, which concluded in pomp on January 28th, ended up backing an only

slightly more sprightly reptile. After eight days of unusually fierce politicking,

party bigwigs forced the charismatic and pro-business prime minister to

leave government after his term expires in a few months. Nguyen Tan Dung

had hoped to assume the top party post of general secretary. Instead Mr

Dung, along with the state president, Truong Tan Sang, failed to get a seat

on the party’s new Central Committee, while the septuagenarian incumbent,

Nguyen Phu Trong, was asked to carry on as all-important party chief.

Given term limits

and mandatory retirement ages, Mr Dung, who is 66, had every reason to be

shown the door. Yet analysts thought he might win promotion to general secretary.

His patronage network is extensive, and he enjoyed the support of business

types backing a more open economy. Younger Vietnamese liked Mr Dung’s friendly

stance towards America and his robust defence of Vietnam’s sovereignty

in territorial disputes with China.

True, whiffs of

corruption hung over him, and the bankruptcies of two state firms he championed

were a blot. But many Vietnamese could accept these things. Despite the

scandals, “he still improved Vietnam’s relations with America”, says Pham

Khac Quang, a 33-year-old machine-parts distributor in Hanoi. Had he kept

on doing that, all else “would have been forgiven”. In December Mr Dung defended

his record in a nine-page memo to colleagues, later leaked to a political

blog.

In the end an opposing

party faction loosely grouped around Mr Trong gained the upper hand, in

part through skilful management of voting procedures that baffle even some

insiders. This group appears to have emphasised Mr Dung’s economic mishaps.

His opponents almost certainly pointed out that his self-promotion and his

anti-China populism were incompatible with the Communists’ preference for

cautious, consensual rule. Some doubtless worried that his rise would undermine

their own power.

As for Mr Trong,

party chief since 2011, he is a colourless apparatchik in the twilight of

his career. His support owes as much to Mr Dung’s divisiveness as to any

personal merits; indeed, with the prime minister out of the picture Mr

Trong may soon retire himself, to be replaced by a bland successor—a front-runner

is the party’s propaganda chief, Dinh The Huynh. More interesting are the

officials the congress appears to have chosen for other top jobs. Nguyen

Thi Kim Ngan looks likely to become the first woman to chair the National

Assembly; she understands economics and is broadly well-regarded. The probable

new state president is Tran Dai Quang, the minister for public security.

He would be a worrying choice, given the state’s tendency to lock up and

occasionally torture dissidents. Human Rights Watch calls its record “dismal”.

The next prime minister

is expected to be Nguyen Xuan Phuc, who is harder to read. As one of Mr

Dung’s deputies he has worked to cut red tape, with the help of some American

funding. A foreign businessman calls him a “straight shooter”. Yet Mr Phuc

has demonstrated little of Mr Dung’s popularity or vim, and he probably

cleaves closer to Mr Trong’s slightly more conservative views.

The new leaders

may slow the pace of economic liberalisation, but they are unlikely to reverse

it. Nor will relations with America be set back. It was Mr Trong, after

all, who delighted in calling on President Barack Obama in Washington last

summer—a big step in attempts to make Vietnam less vulnerable to Chinese

bullying. A party plenum recently reaffirmed its support for the Trans-Pacific

Partnership, an American-led trade deal which the incoming government will

soon have to ratify. Meanwhile, bigwigs at the congress made encouraging

noises about shrinking flabby state firms. Investors will welcome this sense

of consistency, although the prime minister’s imminent departure has also

dashed hopes that grander modernisations might be on the cards.

More radical changes

may have to wait for the next congress, in 2021. Then a mass of Russian-speaking

party members, brought up hating America, are due to retire. Their successors

may well be Western-educated technocrats who understand that the party’s

best hope of survival lies in making the economy more competitive, and in

convincing young Vietnamese such as Mr Quang, the machine-parts distributor,

that it has their interests at heart. For the moment, though, hammer-and-sickle

banners cover the capital. And most people—like subjects in a 15th-century

kingdom—have no say in who rules the roost.

Tìm đọc lại bài này thấy hay quá, copy nguyên văn ra đây

cho ai không vượt tường lửa được... Bài này ai là đảng viên cộng sản thì

nên đọc, ai hiểu cộng sản rồi thì có thể bỏ qua... #DMCS

Một thời lịch sử với Nguyễn Hộ

Chia rẽ về tư tưởng trong hàng ngũ những người cộng

sản sau 1975 đã đưa đến sự ly khai hơn 10 năm sau đó của ông Nguyễn

Hộ, một nhà cách mạng kỳ cựu của miền Nam Việt Nam.

... Continue Reading

Nhắc lại giai đoạn từ bỏ con đường cộng

sản của ông Nguyễn Hộ cuối những năm 1980.

Note: CLB Khiến Chán của đám Miền Nam, đã từng được Xịa phịa ra, trong

thời kỳ chiến tranh.

Cũng hội họp, ra mắt, tuyên bố ly khai với VC Bắc Kít. Tẩy mắc bẫy.

Tờ Le Monde đi trang nhất. Tờ Time, chắc là nhờ Cao Bồi, không. Nhưng lộng

giả thành chân. Sau 1975, quả có, với Nguyễn Hộ. Với VC, chống nó là nó thịt,

đơn giản có vậy

Hannah Arendt, theo GCC là người có thẩm

quyền nhất, theo nghĩa, rất rành, về chủ nghĩa toàn trị.

Hannah Arendt, trong cuốn Từ Dối Trá đến Bạo Lực, chương

Về Bạo Lực, Sur la Violence,

có đưa ra 1 nhận xét, thật tuyệt, nếu áp dụng vào cái cảnh

VC đánh chủ của VC, là nhân dân, như đang xẩy ra.

Bà viết:

Bạo lực càng trở nên

một khí cụ đáng ngờ và không đi đến đâu trong những liên hệ quốc

tế, thì nó lại càng trở nên thật quyến rũ, và thật hữu hiệu ở bên

trong cái gọi là cách mạng…

Marx không phải không

ý thức đến bạo lực trong lịch sử, nhưng ông chỉ ban cho nó 1 vai

trò thứ yếu, cái xã hội cũ đi đến mất tiêu thì không phải do bạo lực

mà là do những mâu thuẫn nội tại… cái gọi là “chuyên chính vô

sản” chỉ có thể được dựng lên sau Cách Mạng và chỉ trong 1 thời

kỳ ngắn…

Plus la violence est devenue

un instrument douteux et incertain dans les relations internationales,

plus elle a paru attirante et efficace sur le plan intérieur,

et particulièreement dans le domaine de la révolution. La rude

phraséologie marxiste de la Nouvelle Gauche s'accompagne des progrès

incessants de la conception non marxiste proclamée par Mao Tsé-toung,

selon laquelle « le pouvoir est au bout du fusil ». Certes, Marx

était parfaitement consscient du rôle de la violence dans l'histoire,

mais ce rôle lui paraissait secondaire; la société ancienne est conduite

à sa perte non par la violence, mais par ses contradictions internes.

L'apparition d'un nouveau type de société est précédée, mais

non provoquée, de convulsions violentes qu'il compare aux douleurs

de l'enfantement qui précèèdent la naissance, mais qui, naturellement,

n'en sont pas la cause. Dans la même ligne de pensée, il estimait

que l'Etat constituait un instrument de violence au service de la classe

dominante, mais cette classe n'exerce pas son pouuvoir en ayant recours

aux moyens de la violence. Il réside dans le rôle de la classe dirigeante

dans la société, ou, plus exactement, dans le processus de production.

On a souvent remarqué, et parfois déploré, que, sous l'influence

des théories de Marx, la gauche révolutionnaire se refusait à utiliser

les moyens de la violence; la« dictature du prolétariat» qui,

selon Marx, devait être ouvertement répressive, ne devait être instaurée

qu'après la Révolution, et ne durer, comme la dictature romaine, qu'une

période de temps limitée; l'assassinat politique, à l'exception de quelques

actes de terrorisme individuel accomplis par de petits groupes d'anarchistes,

fut surtout utilisé par la droite, tandis que les soulèvements armés

et organisés demeuraient principalement une prérogative militaire. La

gauche restait néanmoins convaincue que « toutes les conspirations

sont non seulement inutiles mais nuisibles. Elle [savait] trop bien que

les révolutions ne se font pas d'une façon intentionnelle et arbitraire,

mais qu'elles sont partout et toujours le résultat nécessaire de circonstances

entièrement indépendantes de la volonté et de la direction des partis

et de classes entières de la société.»

Hannah Arendt: Sur

la violence

Hannah Arendt :

Những Nguồn Gốc Của Chủ Nghĩa Toàn Trị.

Lời Tựa lần xuất bản đầu (1951).

Thực vậy, đây là nỗi khốn khó của thời

đại chúng ta, mắc míu lung tung, đan xen lạ lùng giữa xấu và tốt, đến

nỗi, nếu không có "bành trướng để bành trướng" của những tên đế quốc,

thế giới chẳng bao giờ trở thành một; nếu không có biện pháp chính

trị "quyền lực chỉ vì quyền lực" của đám tư sản, cái sức mạnh vô biên

của con người chắc gì đã được khám phá; nếu không có thế giới ảo vọng,

thiên đường mù của những phong trào toàn trị, qua đó, những bất định thiết

yếu của thời đại chúng ta đã được bầy ra một cách thật rõ nét, như chưa

từng được bầy ra như vậy, thì làm sao chúng ta [lại có cơ hội] bị đẩy tới

mấp mé bên bờ tận thế, vậy mà vẫn không hay, chuyện gì đang xẩy ra?

Và nếu thực, là, trong những giai đoạn tối hậu của chủ nghĩa

toàn trị, một cái ác triệt để xuất hiện, (triệt để bởi vì chúng không

thể suy diễn ra, từ những động cơ có thể hiểu được, của con người), thì

cũng thực, là, nếu không có chủ nghĩa toàn trị, chúng ta có thể chẳng

bao giờ biết được bản chất thực sự cơ bản, thực sự cội rễ, của cái ác.

Chủ nghĩa bài Do Thái (không phải chỉ có sự hận thù người

Do Thái không thôi), chủ nghĩa đế quốc (không chỉ là chinh phục), chủ

nghĩa toàn trị (không chỉ là độc tài) – cái này tiếp theo cái khác,

cái này bạo tàn hơn cái kia, tất cả đã minh chứng rằng, phẩm giá của

con người đòi hỏi một sự đảm bảo mới, và sự đảm bảo mới mẻ này, chỉ có

thể tìm thấy bằng một nguyên lý chính trị mới, bằng một lề luật mới

trên trái đất này; sự hiệu lực của nó, lần này, phải được bao gồm

cho toàn thể loài người, trong khi quyền năng của nó phải được hạn chế

hết sức nghiêm ngặt, phải được bắt rễ, và được kiểm soát do những thực

thể lãnh thổ được phân định mới mẻ lại.

Chúng ta không còn có thể cho phép chúng ta giữ lại những

cái gì tốt trong quá khứ, và đơn giản gọi đó là di sản của chúng ta,

hay loại bỏ cái gì là xấu, giản dị coi đó là một gánh nặng chết tiệt mà

tự thân chúng sẽ bị thời gian chôn vùi trong lãng quên. Cái mạch ngầm

của lịch sử Tây phương sau cùng đã trồi lên trên mặt đất, và soán đoạt

phẩm giá của truyền thống của chúng ta. Đây là thực tại chúng ta

sống trong đó. Đây là lý do tại sao mọi cố gắng chạy trốn cái u ám

của hiện tại, bằng hoài vọng một quá khứ vẫn còn trinh nguyên, hay bằng

một sự lãng quên có dự tính về một tương lai tốt đẹp hơn: tất cả những

cố gắng như vậy đều là vô hiệu.

không một tờ báo nào đăng tin linh mục

Chân Tín qua đời. đấy là vị Chủ tịch ủy ban cải thiện chế

độ lao tù miền Nam Việt Nam.Người công bố cho thế giới biết

chế độ chuồng cọp Côn Đảo đã vi phạm nhân quyền như thế nào.

Lịch sử để lịch sử phán xét,

người trí thức chế độ nào cũng vậy nếu vi phạm quyền

con người thì họ lên tiếng.

tôi khinh bọn ăn cháo đá

bát của ngày xưa nếu không có linh mục Chân Tín

, Linh mục Nguyễn Ngọc Lan các ông đã rũ xương trong tù, nay

các ông [ trừ người đã chết ] ăn cháo đá bát.

Thưa người tôi xem là thầy đang

ở nước ngoài và các anh em. tôi không hoàn tất

được việc thầy nhờ để tên trong việc cậy nhờ chia buồn. vì

không báo nào chịu đăng dù tôi sẵn sàng trả đăng tin tiền

sòng phẳng

kwan

RIP

Đây là 1 phần của cái giá

phải trả của đám được coi là Lực Lượng Thứ Ba, tức đám

nằm vùng.

Tất cả đám này, số phận tên

nào cũng thế, than thở cái nỗi gì nữa.

NQT

V/v “ăn cháo đá bát”. Câu này còn có khi được hiểu/viết là,

“ăn cháo đái bát”, và cái nghĩa này, mới đúng, cho 1 số tên nằm

vùng bợ đít VC, trong có tên “người của chúng ta ở Paris”.

GCC đã từng viết về tên này đôi lần rồi, viết thêm, có khi

chúng lại nghĩ Gấu thù oán cá nhân.

Tất nhiên, không, vì thú thực, Gấu không có được cái thú

vui độc ác bịnh hoạn này, tiếc thế, nhưng cái cas của tên này quá quái

đản, thưộc loại siêu, nên đành lại lôi ra. (1)

Cũng Bắc Kít di cư, cũng dân Chu Văn An, bố còn làm giám

thị, cùng học một năm với Gấu, khác lớp, nổi tiếng giỏi toán, được Ngụy

cho đi du học, nằm vùng VC, đã từng làm tà lọt/thông ngôn cho trưởng

phái đoàn Bắc Kít ở hòa đàm Paris….

Những sự kiện đó, cũng thường, vì hắn tin vào chủ nghĩa,

tin vào lý tưởng nước Mít là một, vv và vv.

Nhưng có chuyện này, Gấu không làm sao hiểu nổi. Đó là hắn

cạy miệng người đã chết, để nhét vô miệng những lời nói cực kỳ thô bỉ.

Người này là bố của 1 ông, bạn của hắn. Cũng 1 tên tuổi

trong giới giang hồ, đã từng làm Trùm chương trình tiếng Mít của Đài

Bi Bi Xèo. Ông bố là Ngụy, đi tù VC về, ông con hỏi, tù ra sao, thì tất

nhiên là khổ rồi, đáy địa ngục mà, nhưng giả như ta [Ngụy] mà thắng, thì

khủng khiếp hơn nhiều!

Khủng khiếp hơn nhiều, như thế nào, thì hắn không cho biết,

mà chỉ cho biết, ông bố nói xong, gạt phắt, thôi đừng hỏi chuyện đó

nữa, cái gì đã qua, cho qua luôn!

Cùng học môt năm, hình như thế. Những gì về tên này, Gấu

biết được, là qua 1 anh bạn cùng học.

Đệ tử của Cao Bồi. Bị Xịa gài, trong vụ "một ngàn giọt lệ".

Tuy công lao như thế, vậy mà bị Vẹm cấm cửa, không cho về. Ông chánh

tổng An Nam ở Paris cũng đã từng bị Vẹm cấm cửa!

Được, được!

Cái này thì đành phải khen Vẹm 1 phát!

Gấu là thằng viết lách đầu tiên, dám về trong nước, và được

Vẹm đón tiếp rất ư là niềm nở, thú thế chứ, chúng đâu so được với Gấu!

(1)

Bạn có thể cắt nghĩa, cái sự GCC hay lèm bèm về Cái Ác

Bắc Kít, theo cái cảm tính của Kafka, với Prague của ông:

Trong 1 lá thư cho

bạn, Kafka viết, luần quần trong bất cứ 1 ai, là một con quỉ, nó

gậm đêm, đến tang thương, đến hủy hoại, và điều này, đếch VC, và cũng

đếch Ngụy, hay đúng hơn, đời Mít là như thế:

Nếu bạn đếch phải như thế, thì bạn đếch phải là Mít!

Bạn không thể sống, đúng hơn.

Kafka Poet

Cu Bao

with Bùi Văn Phú

and 18 others.

Đối kháng quyền lực

Vậy là trong vòng 2 năm nữa tôi sẽ bị giam lỏng ở đây.

Tôi không thể chống lại chuyện này vì Nhà nước có công an, quân đội

và nhà tù. Tôi ch...

See

More

Đọc, tên "người của chúng ta ở Paris",

cậy miệng xác chết để nhét lời thô bỉ, đã tởm, nhìn tên này tự sướng,

tởm cũng chẳng thua!

Gấu đã nói rồi, lũ này, mỗi tên tởm một kiểu.

Suốt đời phản kháng!

Có lần Gấu phán, VNCH,

hay Ngụy, có lẽ là chế độ đẹp nhất mà xứ Mít có được, và sau này, không

thể nào lại có được, và sở dĩ được như thế, phần lớn, là nhờ cái nền

của nó, là 1 Miền Nam thiên hòa địa lợi, trọng nhân bằng, nhân ái, chưa

từng biết đến cái ác, cái đói, cái khổ, khác hẳn Miền Bắc. Cuộc chiến

Mít, họ đâu có muốn, và hơn thế nữa, họ đâu có hận thù Miền Bắc. Bầu cử

dân chủ như Miến Điện bây giờ? Cái đó, dân Miền Nam đã hưởng rồi. Họ chọn

người họ thích, tin tưởng, trọng nể vô Thượng Viện, Hạ Viện. Lũ nằm vùng,

rồi Bắc Kít, tìm đủ mọi cách làm thịt nó, kết quả là 1 nước Mít như bây

giờ, lũ khốn này phạm vào tội đại ác, vậy mà bây giờ tự sướng, tụ thổi

bằng những dòng cực tởm. Suốt đời phản kháng? Kít

Trang

Top Ten, trong tháng:

Tình cờ lục lọi báo cũ, GCC lôi ra 1 tờ NYRB,

Dec 20, 2001, trong có lá thư của 1 độc giả, hỏi, nhân 1 bài trước đó,

giả như không có Lenin, thì không có chủ nghĩa CS? Tác giả bài viết “Lenin

& The Radiant Future”, trả lời, khó lắm, vì còn nhiều yếu tố khác,

trong có Marx, và những bài giảng của ông này thì đầy quyền uy, vì thực

[Marx’s teaching is all-powerful because it is true]

[Bỗng như nghe Vương Tân, phán, Vượt Mác, dễ ợt!]

Đem câu hỏi đó vô xứ Mít, liệu Bác Hồ, khi làm bồi tầu, rửa chén

không sạch, bị đại bàng, đầu gấu đánh chết, thì liệu xứ Mít thoát nạn

VC?

Căng, nhể?

Theo GCC, cái chết của xứ Mít, là từ mắc míu ngàn đời, từ thuở

lập nước, với Tẫu. Một mặt chống Tẫu, 1 mặt mở nước về phiá Nam, lịch sử

Mít cứ thế kéo dài, cho đến lúc Bác Hồ làm bồi Tây, rồi qua Tây, vô Đảng

CS Tây, lấy tên Tây, vưỡn OK như thường.

Chỉ đến khi Bác trốn Tẩy đi Moscow, rồi được Moscow phái về TQ,

là kể như số phận xứ Mít ô hô ai tai!

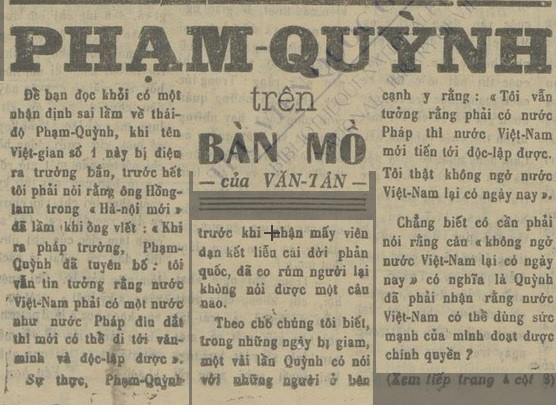

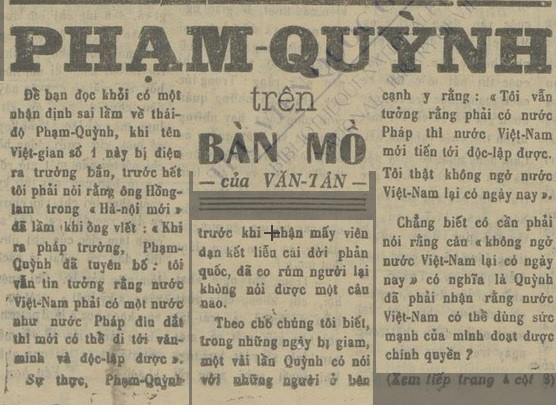

Phạm Quỳnh, vào giây phút

cuối cùng của đời mình, trước khi bị Vẹm làm thịt - trong lúc

đó, Bác Hồ đang bận viết cái thư gửi cho mấy chú Phạm Tuân, con Phạm

Quỳnh, ngày sau lịch sử sẽ minh oan cho cha của các chú - vẫn tin rằng,

phải có thằng Tẩy dìu dắt thì xứ Mít mới khá được.

Graham Greene cũng tin như thế, khi đi những dòng

hoài nhớ chủ nghĩa thực dân thuộc địa của Tẩy ở xứ An Nam ta.

Nhưng những cảm khái trên đây, chỉ có tính

cảm khái. Bây giờ nhìn lại, chúng mang ý nghĩa lịch sử. Vẹm đánh

Tây, là để làm thịt Việt Gian. Đánh Mẽo, để tranh chân làm bồi

Mẽo của Ngụy!

Greene provided surprising support for colonialism,

suggesting the relativity of his political beliefs. Elsewhere he

wrote: 'the writer should always be ready to change sides at the drop

of a hat. He stands for the victims, and the victims change?

In an article for Paris Match he took a more Olympian

view:

It is a stern and sad outlook and, when everything

is considered, it represents for France the end of an empire. The

United States is exaggeratedly distrustful of empires, but we Europeans

retain the memory of what we owe to Rome, just as Latin America knows

what it owes to Spain. When the hour of evacuation sounds there will

be many Vietnamese who will regret the loss of the language which put

them in contact with the art and faith of the West. The injustices committed

by men who were harassed, exhausted and ignorant will be forgotten

and the names of a good number of Frenchmen, priests, soldiers and

administrators, will remain engraved in the memory of the Vietnamese:

a fort, a road intersection, a dilapidated church. 'Do you remember,'

someone will say, 'the days before the Legions left?'

Cái câu cảm khái của Phạm Quỳnh, "không ngờ xứ

Mít khốn nạn như ngày hôm nay", thì cũng giống như quyết định, của

ông cụ của Gấu, không muốn đám con cái của ông sau này, bị nỗi nhục

nhã, bố mày là 1 tên Vẹm.

TTT cũng có ý đó, khi viết:

Chúng nó

say giết người như gạch ngói

Như lòng chúng ta thèm khát tương lai

Cái tương lai của dân Mít, có vẻ như bây giờ mới

ló dạng.

Hãy cho anh khóc bằng mắt em

Những cuộc tình duyên Budapest

Hãy cho anh khóc bằng mắt em

Những cuộc tình duyên Budapest

Anh một trái tim em một trái tim

Chúng kéo đầy đường chiến xa đại bác

Hãy

cho anh giận bằng ngực em

Như chúng bắn lửa thép vào

Môi son họng súng

Mỗi ngã tư mặt anh là hàng rào

Hãy

cho anh la bằng cổ em

Trời mai bay rực rỡ

Chúng

nó say giết người như gạch ngói

Như lòng chúng ta thèm khát tương lai

Hãy

cho anh run bằng má em

Khi chúng đóng mọi đường biên giới

Lùa

những ngón tay vào nhau

Thân thể anh chờ đợi

Hãy

cho anh ngủ bằng trán em

Ðau dấu đạn

Ðêm

không bao giờ không bao giờ đêm

Chúng tấn công hoài những buổi sáng

Hãy

cho anh chết bằng da em

Trong dây xích chiến xa tội nghiệp

Anh sẽ sống

bằng hơi thở em

Hỡi những người kế tiếp

Hãy cho

anh khóc bằng mắt em

Những cuộc tình duyên Budapest

12-56

Let the Past Collapse on Time!

“Dzhugashvili [Stalin] is there,

preserved in a jar,” as the poet Joseph Brodsky wrote

in 1968. This jar is the people’s memory, its collective

unconscious.

“Stalin ở trong đó, được gìn giữ ở trong

1 lọ sành”, như Brodsky viết, vào năm 1968. Cái lọ sành là

hồi ức của dân tộc, cái vô thức tập thể của nó.

“Tẫu Cút Đi”: Trong cái

lọ sành đựng hồi ức của Bắc Kít, hình như đếch có

chỗ dành cho Tẫu, trong cả hai cuộc chiến thần kỳ, chống thực dân

cũ, Pháp, và mới, Mẽo.

“You were not

who you were, but what you were rationed to be”:

Mi không phải là mi, mà là kẻ được

cái chế độ tem phiếu đó nắn khuôn.

Yiyun Li

Cái chuyện Miền Nam, tức Ngụy, chống Tẫu,

thì rõ như ban ngày.

Còn cái chuyện Bắc Kít chống Tẫu,

thì có cái gì đó cực kỳ vô ơn ở trong đó

Không có Tẫu, là cả hai cuộc chiến

không có.

Nhìn rộng ra, nhìn suốt 1 cõi 4 ngàn

năm văn hiến của.. Bắc Kít, có hai yếu tố không có, lòng

nhân từ và lòng biết ơn.

Di chúc Bác Hồ có câu,

ta thà ngửi cứt Tây 5 năm, còn hơn là ngửi cứt Tầu cả

đời. Cái tay viết tiểu sử Graham Greene trích dẫn, nhưng anh ta

thòng thêm 1 câu, Bác nói thì Bác nói, gái Tẫu, Tẫu dâng, Bác

không tha, khí giới Tẫu cung cấp để giết Ngụy, Bác cũng nhận,

gạo Tẫu viện trợ cho Bắc Kít khỏi chết đói, OK hết.

Thu

Ngoc Dinh

Bà Dương Thu Hương, cựu Phó Thống đốc NHNN VN: "Láng giềng

chúng ta sang đây xây dựng làng xã, thành phố rồi!"

Đây là nội dung phát biểu của bà Dương Thu Hương, ...

Thế rồi nhận định nữa là do ‘sự chống phá của các thế lực

thù địch’. Tôi thấy chưa tìm đâu thấy cái chống phá bên ngoài, nhưng

cái niềm tin của dân đã giảm, thì còn nguy hiểm hơn cả thế lực bên ngoài.

Cái điều đó là cái mà tôi cho rằng cần phải đánh giá như thế, chứ còn

ba cái thằng Việt kiều nó về lọ mọ vớ vẩn, không thèm chấp. Tất nhiên

chúng ta vẫn cảnh giác nhưng chưa thấy ai chống phá chúng ta những cái

gì mà gọi là để cho đất nước này đổ cả. Mà tôi chỉ sợ cái lòng dân này

làm cho chúng ta sụp đổ. Nó như là một toà nhà mà bị mối, mặt bên ngoài

toà nhà vẫn rất đẹp nhưng mà nó bị mối hết rồi".

Mời nghe toàn bộ audio tại đây: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ubS8pd28Ua0

Note: Bà này bảnh thực.

Tếu nhất, là, cùng tên với nhà văn DTH!

Cùng các anh chị em chạy lên Đồng Nai "giải cứu" Đỗ

Thị Minh Hạnh và Trương Minh Đức ra khỏi đồn công an Long Bình lúc

gần 2 giờ sáng rồi cùng mọi người đưa cả hai về cấp cứu tại bệnh viện

Hoàn Mỹ Sài Gòn, chừ 3 giờ sáng mới về đến nhà. Còn nhiều anh chị em

vẫn ở lại bệnh viện với Đức và Hạnh.

Công an đã đánh Minh Hạnh và Minh Đức bầm dập, Hạnh bị

tổn thương vùng đầu và khắp người đến mức không đi nổi, anh em phải dìu

ra xe.

Chừ đi ngủ mai sẽ kể nhiều chuyện về vụ bắt và đánh người

hung tợn phi pháp nầy của công an Đồng Nai.

Trần Bang,

Tia Chop Nho,

Nguyễn Hoàng

Vi, Tran Nguyen,

Peter Lam Bui,

Hoàng

Dũng, Tuấn Khanh, Suong Quynh...

Nguyễn Quang

Duy added 3 new photos

— with Ngô Nhật

Đăng and 85 others.

ĐIỀN CHỦ NGUYỄN THỊ NĂM MỘT NHÂN VẬT LỊCH SỬ.

Nguyễn Quang Duy

Khai mạc cuộc triển lãm Cải cách ruộng đất (CCRĐ), ông

Nguyễn Văn Cường, Giám đốc Bảo tàng Lịch s ...

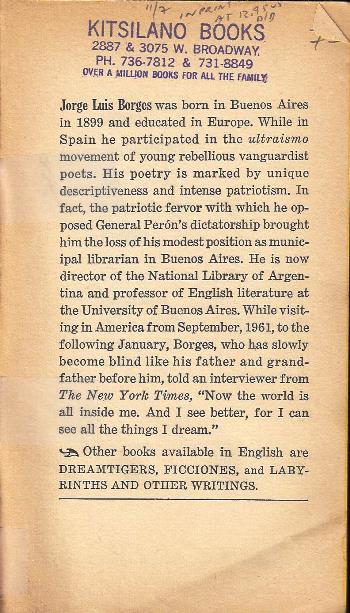

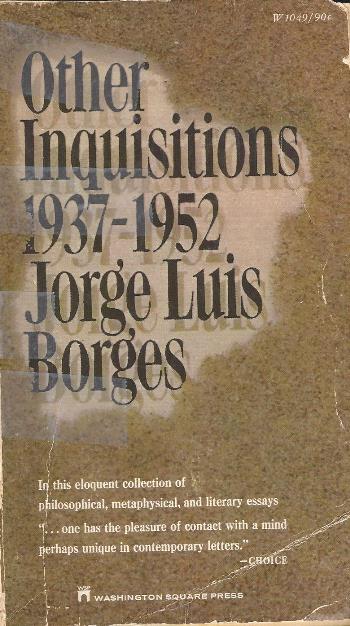

Borges

cho rằng, quan niệm về một âm mưu ghê rợn của Đức nhằm thống trị toàn

thế giới, là quá tầm phào, cà chớn.

"Gấu Nhà Văn" tin rằng Cái Ác Bắc Kít đưa đất nước

Mít xuống hố; Borges, chính cái thứ giáo dục dậy con nít hận thù gây

đại họa.

TV post mấy

đoạn viết của ông, và sẽ số gắng chuyển ngữ, nếu có thể.

NOTES ON GERMANY & THE WAR

JORGE

LUIS BORGES

A Pedagogy of Hatred

Displays of hatred are even more

obscene and denigrating than exhibitionism. I defy pornographers to show

me a picture more vile than any of the twenty-two illustrations that comprise

the children's book Trau keinem Fuchs auf gruener Heid und keinem Jud

bei seinem Eid [Don't Trust Any Fox from a Heath or Any Jew on his Oath]

whose fourth edition now infests Bavaria.

It was first published a year ago, in 1936, and has already sold 51,000

copies. Its goal is to instill in the children of the Third Reich

a distrust and animosity toward Jews. Verse (we know the mnemonic virtues

of rhyme) and color engravings (we know how effective images are) collaborate

in this veritable textbook of hatred.

Take any page: for example, page

5. Here I find, not without justifiable bewilderment, this didactic

poem-"The German is a proud man who knows how to work and struggle.

Jews detest him because he is so handsome and enterprising" -followed

by an equally informative and explicit quatrain: "Here's the Jew, recognizable

to all, the biggest scoundrel in the whole kingdom. He thinks he's wonderful,

and he's horrible." The engravings are more astute: the German is a Scandinavian,

eighteen-year-old athlete, plainly portrayed as a worker; the Jew is a

dark Turk, obese and middle-aged. Another sophistic feature is that the

German is clean-shaven and the Jew, while bald, is very hairy. (It is well

known that German Jews are Ashkenazim, copper-haired Slavs. In this book

they are presented as dark half-breeds so that they'll appear to be the exact

opposite of the blond beasts. Their attributes also include the permanent

use of a fez, a rolled cigar, and ruby rings.)

Another engraving shows a lecherous dwarf trying to seduce

a young German lady with a necklace. In another, the father reprimands

his daughter for accepting the gifts and promises of Solly Rosenfeld,

who certainly will not make her his wife. Another depicts the foul body

odor and shoddy negligence of Jewish butchers. (How could this be,

with all the precautions they take to make meat kosher?) Another, the

disadvantages of being swindled by a lawyer, who solicits from his

clients a constant flow of flour, fresh eggs, and veal cutlets. After a

year of this, the clients have lost their case but the Jewish lawyer

"weighs two hundred and forty pounds." Yet another depicts the opportune

expulsion of Jewish professors as a relief for the children:

"We want a German teacher;' shout

the enthusiastic pupils, "a joyful teacher who knows how to play with

us and maintain order and discipline. We want a German teacher who will

teach us common sense." It is difficult not to share such aspirations.

What can one say about such a book? Personally I am outraged,

less for Israel's sake than

for Germany's,

less for the offended community than for the offensive nation. I don't

know if the world can do without German civilization, but I do know

that its corruption by the teachings of hatred is a crime.

[1937]

1939

Those who hate Hitler usually

hate Germany...

... I naively believe that a powerful Germany would

not have saddened Novalis or been repudiated by Holderlin. I detest Hitler

precisely because he does not share my faith in German people; he has decided

that to undo 1918, the only possible lesson is barbarism ; the best incentive,

concentration camp....

1941

The notion of an atrocious conspiracy by Germany

to conquer and oppress all the countries of the atlas is (I rush to admit)

irrevocably banal. It seems an invention of Maurice Leblanc, of Mr. Phillips

Oppenheim, or of Baldur von Schirach. Notoriously anachronistic, it has

the unmistakable flavor of 1914. Symptomatic of a poor imagination, grandiosity,

and crass make-believe, this deplorable German fable counts on the complicity

of the oblique Japanese and the docile, untrustworthy Italians, a circumstance

that makes it even more ridiculous ... Unfortunately, reality lacks literary

scruples. All liberties are permitted, even a coincidence with Maurice Leblanc.

As versatile as it is monotonous, reality lacks nothing, not even the purest

indigence. Two centuries after the published ironies of Voltaire and

Swift, our astonished eyes have seen the Eucharist Congress; men fulminated

against by Juvenal rule the destinies of the world. That we are readers

of Russell, Proust, and Henry James matters not; we are in the rudimentary

world of the slave Aesop and cacophonic Marinetti. Ours is a paradoxical

destiny.

Le vrai peut quelque fois n'être pas vraisemblable: the unbelievable, indisputable truth is that the

directors of the Third Reich are procuring a universal empire, the

conquest of the world. I will not enumerate the countries they have

already attacked and plundered, not wishing this page to be infinite.

Yesterday the Germanophiles swore that the maligned Hitler did not

even dream of attacking this continent; now they justify and praise

his latest hostility. They have applauded the invasion of Norway and Greece, the Soviet Republics

and Holland;

who knows what celebrations they will unleash the day our cities and

shores are razed. It is childish to be impatient; Hitler's charity is

ecumenical; in short (if the traitors and Jews don't disrupt him) we

will enjoy all the benefits of torture, sodomy, rape, and mass executions.

Do not our plains abound in Lebensraum, unlimited and precious matter?

Someone, to frustrate our hopes, observes that we are very far away,

My answer to him is that colonies are always far from the metropolis;

the Belgian Congo is not on the borders of Belgium.

BORGES: An Essay on Neutrality

CCRD,

lệnh từ Bắc Kinh, Bắc Kít phải làm, là, phải làm.

Giả như để chậm lại, là không có vụ di cư.

Bắc Kít quên ơn Tẫu, nhưng, có thể nói, không có Tẫu không

có Ngụy. Hoặc có, nhưng chết hết ở trong Lò Cải Tạo, nếu Tẫu không dạy

cho VC hai bài học!

Thực hư môn sử bị 'xóa sổ'?

http://www.bbc.com/vietnamese/vietnam/2015/11/151119_hangout_history_teaching

Cái môn sử mà VC nhồi nhét vô đầu con nít, sở dĩ giờ

này lâm đại họa, vì nó quá nhảm. Làm đếch gì có Lê Văn Tám, thí dụ,

và gần đây nhất, là cuộc chiến Mít: Từ trẻ con tới người lớn xứ Bắc

Kít bây giờ thì mới ngã ngửa ra rằng thì là, hóa ra Ngụy chúng sướng

hơn Cách Mạng nhiều, và rõ ràng là chúng “người” hơn nhiều so với thứ

được trồng bằng Cái Ác Bắc Kít.

Không chỉ sử, mà có thể nói cả 1 nền giáo dục Bắc Kít

cần phải xóa sổ, vì đó là 1 nền giáo dục dậy con nít hận thù.

Cái chết của Bắc Kít, là dậy con nít thù hận.

Borges bị Naipaul chửi là cả đời mân mê cái bất tử,

đếch thèm để ý đến đời thực.

Không đúng. Cả đời Borges, bất cứ khi nào ông quan tâm

đến đời thực, là thực sự quan trọng, hết sức cần thiết.

Ông phán, Lò Thiêu, sở dĩ xẩy ra, là vì nước Đức dậy

con nít thù hận. Cái thù hận sắc dân chỉ là cái cớ, dậy con nít thù

hận mới là cái chết của nước Đức.

Hai phát giác thần sầu của Borges liên quan tới Nazi,

đều có gì mắc mớ tới Bắc Kít, và cuộc chiến vừa qua, theo GCC.

Thứ nhất, là nền giáo dục hận thù gây họa.

Thứ nhì, Borges tin rằng Hitler không hề muốn thắng, mà

muốn thua, muốn bại trận.

Gấu chẳng đã từng kể câu chuyện anh bạn cùng học thời

trung học NKL, đi tù cải tạo, 1 lần chuyển trại, đói quá, được 1

bà già Bắc Kít lén cho ăn. Nhìn anh ăn vội vàng, lén lút, bà than,

các cháu đánh đấm ra làm sao mà để thua giặc dữ. Già này đêm ngày

cầu nguyện cho Miền Nam giải phóng Đất Bắc.

Nguyễn Chí Thiện mà chẳng thế sao. Ở tù VC, khi nghe tin

Miền Nam thua trận, ông quá đau lòng.

Còm của Borges về ngày 30 Tháng Tư 1975

A Comment on August 23, 1944

That crowded day gave me three

heterogeneous surprises: the physical happiness I experienced

when they told me that Paris had been liberated; the discovery that

a collective emotion can be noble; the enigmatic and obvious enthusiasm

of many who were supporters of Hitler. I know that if I question that

enthusiasm I may easily resemble those futile hydrographers who asked why

a single ruby was enough to arrest the course of a river; many will accuse

me of trying to explain a chimerical occurrence. Still, that was what happened

and thousands of persons in Buenos Aires can bear witness to it.

From the beginning, I knew that it was useless to

ask the people themselves. They are changeable; through their practice

of incoherence they have lost every notion that incoherence should be

justified: they venerate the German race, but they abhor "Saxon" America;

they condemn the articles of Versailles, but they applaud the marvels

of the Blitzkrieg; they are anti-Semitic, but they profess a religion

of Hebrew origin; they laud sub-marine warfare, but they vigorously condemn

acts of piracy by the British; they denounce imperialism, but they vindicate

and promulgate the theory of Lebensraum; they idolize

San Martin, but they regard the independence of America as a mistake; they

apply the canon of Jesus to the acts of England, but the canon of Zarathustra

to those of Germany.

I also reflected that every other uncertainty was

preferable to the uncertainty of a dialogue with those siblings of chaos,

who are exonerated from honor and piety by the infinite repetition

of the interesting formula I am Argentine.

And further, did Freud not reason and Walt Whitman not foresee that

men have very little knowledge about the real motives for their conduct?

Perhaps, I said to myself, the magic of the symbols Paris

and liberation is so powerful that Hitler's partisans

have forgotten that these symbols mean a defeat of his forces. Wearily,

I chose to imagine that fickleness and fear and simple adherence to

reality were the probable explanations of the problem.

Several nights later a book and a memory enlightened

me. The book was Shaw's Man and Superman; the passage

in question is the one about John Tanner's metaphysical dream, where

it is stated that the horror of Hell is its unreality. That doctrine can

be compared with the doctrine of another Irishman, Johannes Scotus Erigena,

who denied the substantive existence of sin and evil and declared that

all creatures, including the Devil, will return to God. The memory was

of the day that is the exact and detested opposite of August 23, 1944:

June 14, 1940. A certain Germanophile, whose name I do not wish to remember,

came to my house that day. Standing in the doorway, he announced the

dreadful news: the Nazi armies had occupied Paris. I felt a mixture of

sadness, disgust, malaise. And then it occurred to me that his insolent

joy did not explain the stentorian voice or the abrupt proclamation. He

added that the German troops would soon be in London. Any opposition was

useless, nothing could prevent their victory. That was when I knew that

he too was terrified.

I do not know whether the facts I have related require

elucidation. I believe I can interpret them like this: for Europeans

and Americans, one order-and only one is possible: it used to be called

Rome and now it is called Western Culture. To be a Nazi (to play the

game of energetic barbarism, to play at being a Viking, a Tartar, a sixteenth-century

conquistador, a Gaucho, a redskin) is, after all, a mental and moral

impossibility. Nazism suffers from unreality, like Erigena's hells.

It is uninhabitable; men can only die for it, lie for it, kill and wound

for it. No one, in the intimate depths of his being, can wish it to triumph.

I shall hazard this conjecture: Hitler wants

to be defeated. Hitler is collaborating blindly with the inevitable

armies that will annihilate him, as the metal vultures and the dragon

(which must not have been unaware that they were monsters) collaborated,

mysteriously, with Hercules.

J.L. Borges

Borges kể là ngày 14 June

1940, một tay nói tiếng Đức mà tên của người này, ông không muốn nói

ra, tới nhà ông. Đứng tại cửa, anh ta báo tin động trời: Quân đội Nazi

đã chiếm đóng Paris.

Tôi [Borges] thấy trong tôi lẫn

lộn một mớ cảm xúc, buồn, chán, bịnh.

Thế rồi Borges bỗng để ý tới 1

điều thật lạ, là, trong cái giọng bề ngoài tỏ ra vui mừng khi báo tin

[30 Tháng Tư, nói tiếng Bắc Kít, mà không mừng sao, khi Nazi/VC chiếm đóng

Paris/Sài Gòn!], sao nghe ra, lại có vẻ như rất ư là khiếp sợ, hoảng

hốt?

Hà, hà!

Thế rồi anh ta phán tiếp, Nazi/VC

sẽ không tha London. Và không có gì ngăn cản bước chân của Kẻ Thù

Nào Cũng Đánh Thắng!

Và tới lúc đó, thì Borges hiểu,

chính anh ta cũng quá khiếp sợ!

Cũng tới lúc đó, Borges hiểu

ra "chân lý": Hitler muốn thua trận: Hitler wants to be defeated.

Đọc tới đó, thì Gấu nhớ ra cái

bà già nhà quê Bắc Kít đã từng lén VC cho bạn của Gấu, sĩ quan cải

tạo 13 niên, tí ti đồ ăn, trong 1 lần chuyển trại tù. Bà lầm bầm,

khi nhìn bạn của Gấu nuốt vội tí cơm, các cháu đánh đấm ra làm sao

mà để thua giặc dữ. Già này ngày đêm cầu khẩn các cháu ra giải phóng

Đất Bắc Kít!

NOTES GERMANY &

ON THE WAR

A Pedagogy of Hatred

Displays of hatred are even

more obscene and denigrating than exhibitionism. I defy pornographers to

show me a picture more vile than any of the twenty-two illustrations that

comprise the children's book Trau keinem Fuchs auf gruener Heid und keinem

Jud bei seinem Bid [Don't Trust Any Fox from a Heath or Any Jew on his

Oath] whose fourth edition now infests Bavaria. It was first published

a year ago, in 1936, and has already sold 51,000 copies. Its goal is to instill

in the children of the Third Reich a distrust and animosity toward Jews.

Verse (we know the mnemonic virtues of rhyme) and color engravings (we know

how effective images are) collaborate in this veritable textbook of hatred.

Take any page: for example, page 5. Here I find, not without justifiable

bewilderment, this didactic poem-"The German is a proud man who knows

how to work and struggle. Jews detest him because he is so handsome and

enterprising" -followed by an equally informative and explicit quatrain:

"Here's the Jew, recognizable to all, the biggest scoundrel in the whole

kingdom. He thinks he's wonderful, and he's horrible." The engravings are

more astute: the German is a Scandinavian, eighteen-year-old athlete, plainly

portrayed as a worker; the Jew is a dark Turk, obese and middle-aged. Another

sophistic feature is that the German is clean-shaven and the Jew, while

bald, is very hairy. (It is well known that German Jews are Ashkenazim,

copper-haired Slavs. In this book they are presented as dark half-breeds

so that they'll appear to be the exact opposite of the blond beasts. Their

attributes also include the permanent use of a fez, a rolled cigar, and ruby

rings.)

Another engraving shows a lecherous dwarf trying to seduce a young

German lady with a necklace. In another, the father reprimands his daughter

for accepting the gifts and promises of Solly Rosenfeld, who certainly

will not make her his wife. Another depicts the foul body odor and shoddy

negligence of Jewish butchers. (How could this be, with all the precautions

they take to make meat kosher?) Another, the disadvantages of being swindled

by a lawyer, who solicits from his clients a constant flow of flour, fresh

eggs, and veal cutlets. After a year of this, the clients have lost their

case but the Jewish lawyer "weighs two hundred and forty pounds." Yet another

depicts the opportune expulsion of Jewish professors as a relief for the

children: "We want a German teacher;' shout the enthusiastic pupils, "a

joyful teacher who knows how to play with us and maintain order and discipline.

We want a German teacher who will teach us common sense." It is difficult

not to share such aspirations.

What can one say about such a book? Personally I am outraged, less

for Israel's

sake than for Germany's,

less for the offended community than for the offensive nation. I don't know if the world can do without

German civilization, but I do know that its corruption by the teachings

of hatred is a crime.

[1937]

Jorge

Luis Borges: Selected Non-Fictions,

Penguin Books

Người dịch: Suzanne Jill Levine

*

Note: Tình cờ vớ được bài trên, Sư Phạm của Hận Thù, đọc, Gấu bỗng nhớ

đến bài viết Còn Lại Gì? của PTH,

thí dụ, những đoạn dậy toán bằng đếm xác Mỹ Ngụy...

I don't know if the world can

do without German civilization, but I do know that its corruption by the

teachings of hatred is a crime.

Tôi không biết thế giới làm ăn ra sao, nếu thiếu nền văn minh

Đức, nhưng tôi biết, cái sự sa đọa, hư ruỗng của nó, do dậy dỗ hận thù,

và đây là 1 tội ác.

Cái

việc dậy con nít hận thù là một tội ác. Cái sự thắng trận và băng hoại sau

đó, chính là do dậy con nít thù hận. We want a German

teacher who will teach us common sense: Chúng em muốn 1 ông thầy dậy

chúng em lương tri. (1)

Borges có mấy

bài viết, có tính "dấn thân, nhập cuộc", được gom lại thành 1 cục, có tên

là "Ghi chú về Đức & Cuộc Chiến", trong tuyển tập Selected Non-Fictions, Penguin Books.

Bài trên, như

tiên tri ra được Bắc Kít sẽ thắng cuộc chiến Mít, nhờ dạy con nít thù

hận.

Còn bài nữa, cũng tuyệt lắm: "Một cuộc triển lãm gây bực mình",

“A Disturbing Exposition”. Bài này thì lại mắc mớ đến cái vụ khu trục

đám nhà văn Ngụy ra khỏi nền văn học VC.

Người Mẹ trong tác phẩm của Kincaid

Bài dịch này, cũng là từ hồi mới qua

Canada, 1997. Ng. Tuấn Anh cũng là bút hiệu của Gấu Cà Chớn

Đọc bản tiếng

Anh 1 phát, là trúng đòn liền, vì Gấu cũng 1 thứ

không thương Mẹ mình, và đây là độc hại di truyền từ bà nội

Gấu.

Bà rất thù cô con dâu, và đổ diệt

cho mẹ Gấu, vì ngu dốt quá, khiến chồng bị chúng giết.

Bà

cụ Gấu do tham phiên chợ cuối năm 1946, tại Việt Trì, và

khi trở về làng quê bên kia sông, tay thủ lãnh băng đảng

chiếm Việt Trì lúc đó, là 1 tên học trò của ông cụ, đã đưa

cái thư mời dự tiệc tất niên, nhờ bà đưa cho chồng. Nhận được thư,

đúng bữa ba mươi Tết, ông cụ đi, và mất tích kể từ đó. Gấu

đã viết về chuyện này trong Tự Truyện.

Lần trở lại đất Bắc, Gấu muốn tìm hiểu

coi cụ mất đích thực ngày nào, và thắp 1 nén hương cho

bố mình.

Bãi

sông Việt Trì, nơi ông cụ Gấu mất. Khi Gấu về, cầu đang

thi công. Gấu xuống xe, thắp hương, cúng, khấn

Bố.

Bà chị Gấu không xuống xe. Hình như

Bà chưa lần nào cúng Bố.

Cúng Mẹ thì lại càng không.

Note: Bản trường ca, hoá

ra là trang Tin Văn, chỉ để tố cáo Cái Ác Bắc Kít.

Kincaid viết về quê hương

của Bà:

Bạn cứ tới những nơi chốn, nơi

cái xiềng thuộc địa thật sự bằng thép, và tỏ ra hết

sức hữu hiệu: Phi Châu, vùng Caribbean, hay một nơi nào khác

trên địa cầu. Phi Châu là một thảm họa. Tôi không hiểu đất đai con

người ở đây rồi có ngày lành mạnh trở lại, hay là không. Thật khó

có chuyện, những ông chủ thuộc địa bỏ qua, không đụng tới cái phần

tâm linh của con người Phi Châu. Bởi vậy, chuyện tiểu thuyết hóa là

đồ dởm. Những người Phi Châu đối xử với nhau thật là độc ác; bạn chỉ

việc nhìn tất cả những con người đói khát đó thì thấy. Làm sao có chuyện

những ngài thủ lãnh Phi Châu nhìn vào mặt con dân của họ, và rớt nước

mắt? Họ cứ tiếp tục duy trì, theo một con đường tệ mạt khốn kiếp, cái

điều đã xẩy ra khi còn chế độ thuộc địa. Sự thực, là bất cứ đâu

đâu, cái gọi là di sản của chủ nghĩa thuộc địa, đó là: độc

ác, tàn nhẫn, trộm cướp. Cách những tên thực dân đối xử: mild way,

nhẹ nhàng thôi, đôi lúc có xoa đầu những người dân cô lô nhần,

bây giờ chúng ta đối xử với nhau, theo một cách cay độc hơn, khốn

kiếp hơn. Và bạn biết không, chúng ta cứ mắm môi mắm lợi, lấy hết

sức lực ra, full force, để mà "chơi" nhau. Bởi vậy, có thể dưới luật

thuộc địa, người Phi Châu ăn rất ít; dưới luật của người Phi Châu,

họ chẳng ăn gì hết - và cứ như thế.

Có

1 cái gì đó, y chang xứ Bắc Kít, thời Pháp Thuộc.

Khi vô Nam, là Gấu nhận ra liền, xứ này

không giống xứ Bắc Kít, và Gấu mơ hồ hiểu ra, sự khác biệt

là do đâu. Gấu nhớ, hồi mới vô Sài

Gòn, lần đầu vô 1 quán ăn xã hội, chỉ phải mua đồ ăn, cơm

tha hồ ăn, khỏi trả tiền, thằng bé Bắc Kít sững người, ú a ú ớ…. Rồi những lần đi chơi Bình

Dương, vào vườn chôm chôm, cũng tha hồ ăn, nhưng đừng

mang về, rồi, rồi, chỉ đến khi vô tù VC, thì mới gặp lại xứ

Bắc Kít ngày nào.

Mít vs Lò Thiêu Người

ĐÁNH ĐẾN LUẬT SƯ ĐANG HÀNH NGHỀ LÀ CÙNG ĐƯỜNG RỒI

Điều đó càng chứng tỏ cái chết của em Đỗ Đăng Dư không phải do bạn

tù gây ra như công an Hà Nội thông báo.

Luật sư đoàn Hà Nội, hội luật sư Hà Nội, hội Luật Sư VN không thể

đứng ngoài cuộc khi hội viên của mình bị hành hung đang lúc hành nghề

Cả hai luật sư đều bị đánh Ls Trần Thu Nam và LS Lê Luân

Lũ cướp VC đi đến đỉnh cao của Cái Ác Bắc Kít rồi.

Ai chống nó, là nó thịt.

Một đất nước mà côn đồ làm chủ thì hết thuốc chữa!

VC, từ “một mùa thu năm qua cách mạng tiến ra” [Phạm Duy tán tỉnh kháng

chiến, sau thua, về thành], sử dụng, một và chỉ một mà thôi, đòn nhơ bửn

này. Thủ tiêu, khủng bố, vu oan - Việt gian, Ngụy, Tề - tất cả những ai

chống lại chúng.

Ông cụ của Gấu, sở dĩ không theo chúng là vì vậy. Ông quá tởm chúng,

có thể do đã từng chứng kiến 1 vụ thủ tiêu, một người lương thiện không

chịu theo chúng. Ông cố tránh cho con cái, không trở thành, con của 1 tên

Vẹm. Gấu trở về lại Đất Bắc, và vỡ ra điều này, và đây đúng là món quà tuyệt

vời ông để lại cho con cái, sau khi bị 1 tên học trò thủ tiêu, do quá tin

tưởng vào nó.

Ui chao, lại nhớ đến Bà Trẻ của Gấu, người đã từng nuôi Gấu cho đến

khi ăn học thành tài. Khi Gấu đậu cái bằng Tú Tài Hai, thấy Cảnh Sát Gia

Định tuyển biên tập viên, bèn nạp đơn, bèn OK liền, bèn về khoe với Bà Trẻ,

bà quát, đến, lấy lại cái đơn xé bỏ, nhà mày không có mả đánh người!

Sách & Báo

Primo Levi Page

Viết mỗi ngày

Sách Báo

Ui

chao, đọc chỉ cái tít, là bèn nhớ ra liền cái cảm giác lần đầu tiên được

ăn cái món thịt hun khói, jambon parfumé, khi được bà cô, Cô Dung đem về

nuôi, cho ăn học, những ngày ở Hà Nội.

Nó ngon khủng khiếp đến nỗi Gấu quên con ốc nhồi ở ao làng Thanh Trì,

Quốc Oai Sơn Tây.

Chỉ đến khi đi làm Bưu Điện, có tí tiền còm rồi, thì con ốc nhồi mới thức giấc, phán, đi chứ.

Ghi chú trong ngày

Đọc bài viết của NL, thì GCC

lại nghĩ đến 1 trong những ẩn dụ, ở đầu cuốn dạy tiếng Anh, mà cái tít của

nó, là từ bài thơ của Frost, "Dừng ngựa bên rừng chiều tuyết phủ", trong

có câu, tôi còn những lời hứa, trước khi lăn ra ngủ, Promises To Keep.

Một trong những lời hứa phải

giữ, là 1 ẩn dụ, mà GCC tóm tắt sau đây.

Ẩn dụ này khiến GCC tự hỏi, nếu Cái Ác Bắc Kít gây họa, thì liệu, Cái

Đói Bắc Kít, thay vì Cái Đẹp của Dos, sẽ cứu chuộc… thế giới?

Có 1 anh chàng khi còn nghèo

khổ, được ăn 1 trái chuối, nhớ hoài, đến khi giầu có, tha hồ ăn chuối, thì

không làm sao thấy ngon như lần đầu.

Cái trái chuối đó, với GCC là

con ốc nhồi, vớt được ở cái ao, ở bên ngoài cổng nhà cô Hồng Con, cô con

gái địa chủ, sau này bị cả làng của GCC bỏ cho chết đói, và trong đêm, đói,

bịnh, khát nước [do sốt thương hàn], bò ra khỏi nhà,

tới ao, bò lết xuống, chết ngay ở bờ ao.

GGC nhớ hoài, con ốc nhồi nằm

dưới 1 đám bèo. Gấu gạt đám bèo, con ốc lộ ra, chưa kịp lặn, là thằng cu

Gấu hớt liền. Bèn nổi lửa ngay bên bờ ao, chơi liền.

Sau này, vào Nam, Gấu quá mê

món bún ốc, nhất là của cái bà có cái sạp ở Passage Eden, 1 phần là vậy.

Cũng là cái trái chuối trong ẩn dụ kể trên. Và từ đó, là vấn nạn, cái

đói BK cứu chuộc thế giới.

Còn 1 quán bún ốc, ở trong 1 cái hẻm, kế bên rạp chiếu bóng ngay đường

Lê Lợi, quán Ba Ba Bủng, hình như vậy, cũng ngon, nhưng không bằng.

SAIGON 1967 - Đường Thủ Khoa Huân

Bên trái hình có quán bún chả và bún riêu của bà Ba Bủng rất nổi tiếng

thời xưa của giới Bắc Kỳ 54 ngày xưa trước 1975...!!!

manhhai

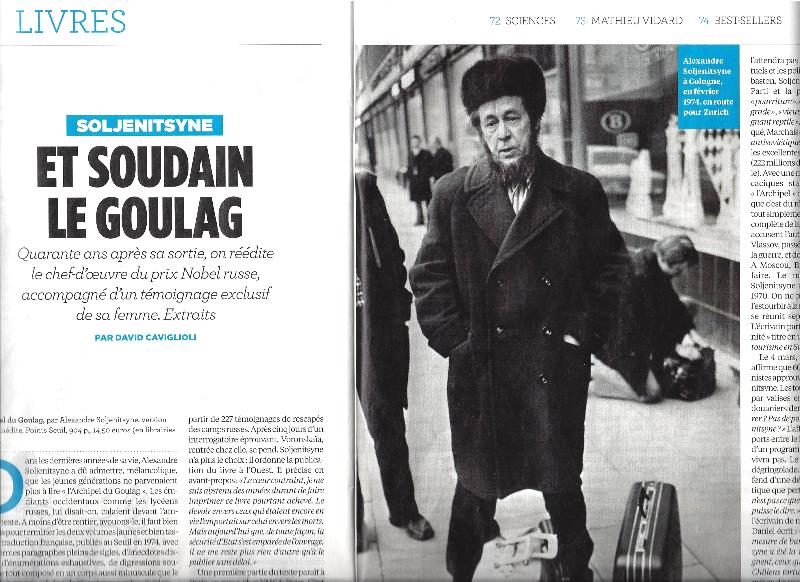

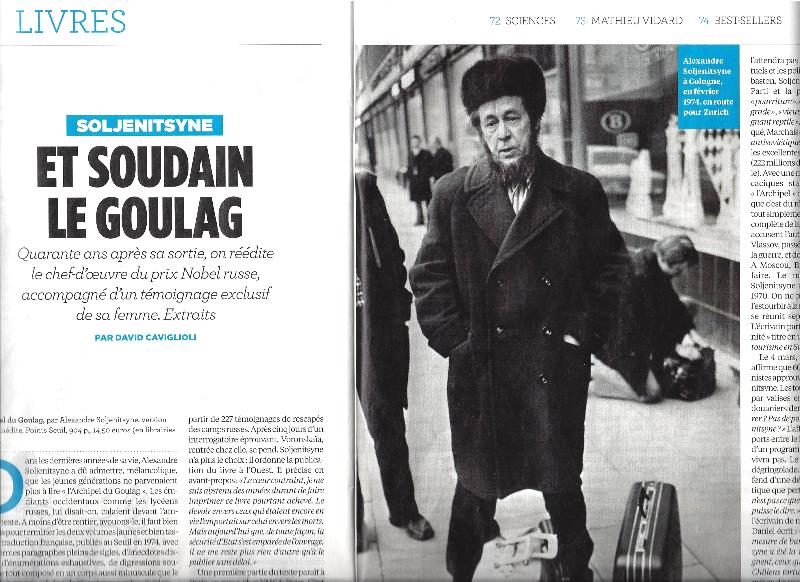

Có lẽ chưa có 1 nhà văn nào bảnh như Solz, ấy là nói về niềm

tin: Ngay từ khi bị tống ra khỏi đất nước, là đã yên chí, ta sẽ trở về,

và khi đó, chế độ Xô Viết đã sụp đổ.

Ông phán điều này, trên đài truyền hình Pháp, trong 1 chương trình

văn học do Bernard Pivot phụ trách, thời gian 1975, khi cuộc chiến Mít đi

vào khúc chót. Ông phán, Miền Bắc sẽ làm thịt Miền Nam, và đây là 1 cuộc

chiến tranh chấp quyền lợi giữa các đế quốc.

Octavio Paz sửa sai, nói, đây là cuộc chiến giải phóng của 1 cựu thuộc

địa.

Bây giờ, điều Solz phán, đã được chứng nghiệm.

Tẩy vẫn khoe, CS Mít, gốc Tẩy..

Đúng, cho tới khi HCM thoát được sự canh chừng của Cớm Tẩy, qua Moscow,

và để không bị Xì trừ khử, như 1 tên thuộc đám cựu trào, nhận làm cớm

CS quốc tế, hoạt động tại TQ.

Lần Gấu về lại Đất Bắc, coi gia phả dòng họ Nguyễn, ông chú ông bác

nào cũng khoe, tô đậm, những dòng, đã từng được du học ở TQ, là Gấu biết,

chết rồi.

Và, bất thình lình, bắt được anh Tẫu, ở trong phòng ngủ nhà

Bắc Kít của mình!

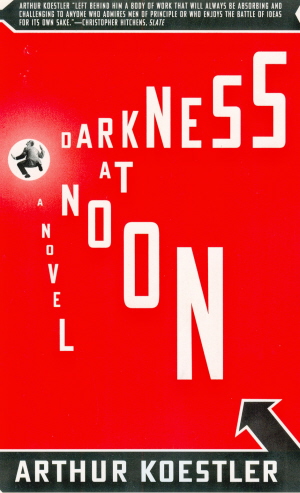

(1) Mới dinh cuốn Bóng Đêm từ một tiệm sách cũ về, cùng

với cuốn Bộ lạc thứ 13:

The Thirteenth Tribe, written near the end of his life, attempted to

prove that Ashkenazi Jews - the main body of European Jewry - were not

ethnic Jews at all but the descendants of the Khazars, Turkic nomads from

Asia who had converted to Judaism

in the eighth century. To the dismay of most Jews, the book was a huge

success and is still quoted with delight by Israel's

hostile neighbors.

Neal Ascherson: Raging towards Utopia

Gấu đọc lại

Đêm giữa Ngọ, để kiểm tra trí nhớ, và để sống lại những ngày mới vô Sài

Gòn.

Quả có mấy

xen, thí dụ, Ông số 2 đang đêm bị hai chú công an đến tóm, và ông ra lệnh

cho chú công an trẻ măng, cách mạng 30 Tháng Tư, lấy cho tao cái áo đại

quân thay vì đứng xớ rớ mân mê khẩu súng! Có cái xen ông số 2 dí mẩu thuốc

đỏ hỏn vô lòng bàn tay, và tưởng tượng ra cái cảnh mình đang được đám đệ

tử tra tấn. Có câu chuyện thê lương về anh chàng ‘Rip của Koestler’ [Giá mà

Bác Hồ hồi đó, khi ở Paris,

đọc được, thì chắc là hết dám sáng tác Giấc Ngủ 10 năm, có khi còn từ

bỏ Đảng cũng nên!]

Thà chơi bửn mà thắng, còn hơn chơi đẹp mà thua!

Trong lúc rảnh rỗi, tôi viết một cuốn

tiểu thuyết Tới và Đi, Arrival and Departure, và một số tiểu luận,

sau được đưa vô The Yogi and the Commissar [Du Già và Chính Uỷ]

Tới và Đi là tập thứ ba, trong một bộ ba tập,

trilogy, trong đó, đề tài trung tâm của nó là cuộc xung đột giữa đạo đức

và thiết thực [expediency: miễn sao có lợi, thủ đoạn, động cơ cá nhân –

khi nào, hoặc tới mức độ nào, thì một cứu cánh phong nhã [vẫn còn có thể]

biện minh cho một phương tiện dơ bẩn. Đúng là một đề tài Xưa như Diễm, nhưng

nó ám ảnh tôi suốt những năm là một đảng viên CS .

Tập đầu của bộ ba, là Những tên giác

đấu, The Gladiators, kể cuộc cách mạng [revolution] của những nô

lệ La mã, 73-71 BC, cầm đầu bởi Spartacus, xém một tí là thành công, và cái

lý do chính của sự thất bại, là, Spartacus đã thiếu quyết định [lack of determination]

– ông từ chối áp dụng luật quay đầu, trở ngược, “law of detours”; luật này

đòi hỏi, trên con đường đi tới Không Tưởng, người lãnh đạo phải “không thương

hại nhân danh thương hại”, ‘pitiless for the sake of pity’. Nôm na là, ông

từ chối xử tử những kẻ ly khai và những tên gây rối, không áp dụng luật

khủng bố - và, do từ chối áp dụng luật này khiến cho cuộc cách mạng thất

bại.

Trong Bóng

đêm giữa ban ngày, tay cựu truởng lão VC Liên Xô Rubashov đi ngược

lại, nghĩa là, ông theo đúng luật trở ngược đến tận cùng cay đắng - chỉ

để khám phá ra rằng ‘lô gíc không thôi, là một cái la bàn không hoàn hảo,

nó sẽ đưa con người vào một chuyến đi đầy dông bão, cuối cùng bến tới biến

mất trong đám sương mù.’

Hai cuốn, cuốn nọ bổ túc cho cuốn kia, và cả hai đều tận cùng bằng

tuyệt lộ.

Tribute to Koestler

In the next

TLS

Jeremy Treglown:

Whoever reads Arthur Koestler now?

Ai còn đọc K. bây giờ?

Có tớ, đây!

Bây giờ gần như mọi người đều quên ông [Koestler], nhưng đã có thời,

tất cả những sinh viên với tí mầm bất bình thế giới, họ đọc ông. Những sinh

viên, đám cháu chít của họ, hay đám trí thức “của” ngày mai, họ chẳng hề

nghe nói đến ông. Một số nhà phê bình nghĩ, sự lãng quên này thì là do những

cái nhảm nhí trong cuộc đời riêng tư của ông, hầu hết được hé lộ sau khi

ông mất: hiếp bà này, trấn bà kia, và nhất là, cái tội ép bà vợ trẻ sau cùng

cùng đi với ông trong chuyến tầu suốt. Lời giải thích sau đây thoả đáng hơn:

thời gian thay đổi. Nội dung trọn một khối của tất cả những gì mà Koestler

sống, sống sót, chiến đấu, rao giảng, lên lớp… - thời những độc tài toàn

trị, những vận động, huy động, chuyển vận… mang tính thiên niên kỷ, những

cuộc chiến toàn thể - đã biến mất. Và biến mất cùng với nó (cũng còn một tí

xíu chưa chịu biến mất), là những chọn lựa đạo đức cổ điển choàng lên lương

tâm, ý thức, [và trên vai ta đôi vầng nhật nguyệt] của hàng bao nhiêu con

người, đàn ông đàn bà của thế kỷ 20: Liệu có nên hy sinh ngày hôm nay để

có một ngày mai ca hát? Thà trốn lính chứ đừng nhẩy toán? Liệu có nên khứng

chịu con quỉ 1 sừng để tránh con quỉ 2 sừng, 10 sừng, liệu có nên đổ xuống

sợi xiềng thực dân cũ, thực dân mới máu của 3 triệu dân Mít [đứng vùng lên

gông xích ta đập tan] để có được một cái nhà nhà Mít to đẹp hơn, đàng hoàng

hơn?

Cái sự vô cảm mà tên già NN chửi đám trẻ ở trong nước, và Thầy Kuốc

ở hải ngoại, chính là vì họ không chịu chết nữa, cho những kẻ suốt đời

sống bằng máu của kẻ khác.

Bao nhiêu thế hệ Bắc Kít đã chết vì giấc mơ thống nhất?

Không đơn giản đâu.

Tên Bắc Kít LDD, suốt 1 đời chửi Mỹ Ngụy, có dịp, là bèn chuồn qua

Mẽo, làm bồi Mẽo, vậy mà có dịp là chọc quê lũ Ngụy.

Chưa hết, hắn cũng bày đặt chửi trong nước, vô cảm, trước hiện tượng

thái tử, công chúa Đỏ.

Cái tít cuốn của VTH, đúng là chôm từ

Koestler. Đâu có dễ mà kiếm ra 1 cái tít hoành tráng như thế. Cái tít Vòng

Tròn Ma Thuật, đúng là cái tít đầu tiên, bằng tiếng Đức, sau được dịch qua

tiếng Anh là Vòng tròn ma quỉ, vicious. Trong 1 bài viết trên talawas, dịch

giả tiếng Việt của nó cho biết, tính dùng cái tít Bóng Đêm Giữa Ban Ngày,

nhưng “của” VTH mất rồi!

Một tên chôm chĩa cuối cùng biến thành sở hữu chủ!

Mới xẩy ra vụ, tác giả giải Man Booker Á Châu, bị tố đạo văn.

Thoạt đầu bà chối, nhưng sau nhận.

Tờ Người Kinh Tế, biết vụ này, vẫn khen tới chỉ tác phẩm của bà.

(1)

Mít, 1 ông nhà văn, người tù vì lương tâm, như VHT, liệu

có tí can đảm, nhận, tớ có chôm cái tít của Koestler?

Cái vụ đạo thơ đang ì xèo, theo Gấu không liên quan tới đạo, mà

là ganh ăn.

PXN cũng đã từng bị talawas đánh, vì ganh ăn, đến nỗi sinh mệnh

chính trị - nồi cơm - có nguy cơ bị bể, Sến mới tha. PHT bổng lộc nhiều

quá, như PXN, chúng ghét, xúm lại đập.

Đạo gì đâu. Hai bài thơ, khác hẳn nhau. Một tên lưu vong, mù tịt

tiếng mũi lõ, không làm sao hội nhập xứ người, nhớ quê hương, khi tôi chết

nhớ quăng cái xác của tôi xuống biển, cho sóng đưa về xứ Mít, thì cũng giống

như PD năn nỉ, cho tớ về, không lẽ tớ chết, chôn ở Bắc Cực ư? Tên nào thì

cũng có bẩn ý cả. Cả hai đều về cả.

*

Người dịch cho rằng sẽ rất

hợp lý nếu chuyển ngữ tên tác phẩm này thành Đêm giữa ban ngày nếu như

trước đó chưa có một tác phẩm đã rất nổi tiếng cùng tên của nhà văn Vũ Thư

Hiên.

PMN

Đấy là ông viết. Còn trong bụng, ông nghĩ: Tay

mũi lõ này ăn cắp cái tít của "bạn ta", là VTH!

Xin trao thi sĩ vòng hoa tặng

Auden, nhà thơ người Anh, khi được hỏi,

hãy chọn bông hoa đẹp nhất trong vòng hoa tặng, ông cho biết, bông hoa đó

đã tới với ông một cách thật là khác thường. Bạn của ông, Dorothy Day, bị

bắt giam vì tham gia biểu tình. Ở trong tù, mỗi tuần, chỉ một lần vào thứ

bẩy, là nữ tù nhân được phép lũ lượt xếp hàng đi tắm. Và một lần, trong đám

họ, một tiếng thơ cất lên, thơ của ông, bằng một giọng dõng dạc như một

tuyên ngôn:

"Hàng trăm người sống không cần tình yêu,

Nhưng chẳng có kẻ nào sống mà không cần nước"

Khi nghe kể lại, ông hiểu rằng, đã không vô ích, khi làm thơ.

Chúng ta đã thắng trước cuộc đời.

Cũng trong cuộc phỏng vấn,

khi được hỏi, ông làm thơ cho ai, Auden trả lời: nếu có người hỏi tôi như

vậy, tôi sẽ hỏi lại, "Bạn có đọc thơ tôi?" Nếu nói có, tôi sẽ hỏi tiếp,

"Bạn thích thơ tôi không?" Nếu nói không, tôi sẽ trả lời, "Thơ của tôi không

dành cho bạn."

Tôi tản mạn về một nhà thơ nước ngoài như trên, là

để nói ra điều này: thế hệ nhà thơ nào cũng muốn chứng tỏ một điều: chúng

tôi không vô ích, khi làm thơ. Nếu mỗi thế hệ là một quốc gia non trẻ ,

và, nếu thế hệ đàn anh của chúng tôi tượng trưng cho nước Việt non trẻ

- vừa mới giành được độc lập - là bước ngay vào cuộc chiến, và, họ đã chứng

tỏ được điều trên: đã không vô ích khi làm thơ; và đã thắng trước cuộc đời,

cho nên đây là một thách đố đối với những nhà thơ trẻ như chúng tôi: đừng

làm cho thơ trở thành vô ích. Và nếu thơ của lớp đàn anh chúng

tôi đã làm xong phần đóng góp cho sự nghiệp chung của dân tộc, thơ của thế

hệ trẻ chúng tôi có lẽ sẽ làm nốt phần còn lại: thơ sẽ nói lên nghệ thuật

của sự tưởng niệm, và mỗi bài thơ, được viết đúng lúc như thế đó, sẽ trở

thành một khúc kinh cầu. Đó là tham vọng của thơ trẻ.

Note: Bài viết này, có phần đóng

góp của Gấu.

Nhớ, gửi cho PTH, VB, anh mail, reply, phần đầu OK.

Phần sau, dởm.

Gấu Cái lắc đầu, anh PTH giỏi thật!

Lướt net, thấy PHT lại dính thêm

1 đòn nữa.

Theo Gấu, vẫn không phải đạo.

Với vụ Du Tử Cà, có thể dùng 1 hình ảnh, đốt ngọn nến hai đầu, để

diễn tả cùng 1 hình ảnh, của kẻ ở bên ngoài, và kẻ ở bên trong, cùng hãy

ném thây tôi xuống biển.

Vụ mới này, Mai Thảo gọi là thơ đồng phục, nghĩa là dở như nhau, ai

đạo của ai thì cũng thế.

Có thể, chính vì thế mà PHT mới nói, bài thơ của tôi in sau, bài của

bạn in trước, [chúng giống nhau vì cùng tệ như nhau].

Thứ thơ tản mạn bên ly cà phê, ngồi bên ly cà phê nhớ người yêu &

bạn quí… quá cả đồng phục mà đúng là 1 trận Đại Hồng Thuỷ của 1 cõi thơ

Mít, từ trong nước tới hải ngoại.

Borges có câu, thơ là để trao cho

thi sĩ.

Câu thơ sau đây, của PHT, không ai đạo được, đúng thứ thơ để trao cho

thi sĩ:

buồn tập tễnh

về ăn giỗ mình

Tuy nhiên, thứ thơ mà mỗi bài thơ

là 1 tưởng niệm, PHT không làm được.

Chắc là do bổng lộc nhiều quá.

Và, nếu như thế, thì

đây đúng là lúc, để, thay vì Huyền Thư, thì là Phần Thư?

"Về ăn giỗ mình", là... lúc này?

Sẹo Độc Lập vs Điêu Tàn ư đâu chỉ có

Điêu Tàn?

Tôi chỉ ngạc nhiên về sự phi logic mà ít người nhận ra "làm

thế nào để chị Thường Đoan đạo thơ của Phan Huyền Thư khi mà chính chủ

nhân của nó giấu kỹ thơ trong hộc bàn của mình, chả ai biết cả từ năm 1996?

Hay chị Thường Đoan có chìa khóa buồng nhà Thư? Hay một nhà thơ ở VN có

thể đặt Hợp Lưu và Tạp chí Thơ dài hạn nên đọc được bài thơ trên đó, trong

khi chính tác giả cũng không biết hai tạp chí trên có đăng hay không"? Thư

thật thiếu dũng cảm nhận lỗi! Minh Quang Hà

Tho Nguyen Van@Thai

Lê Thị Thái Hoà

Đấng này, bạn thân của PHT, vậy mà cũng

đánh hôi!

Xin đừng làm chữ của tôi đau

Nguyễn Huy Thiệp

viết về PHT

Cái giờ nghiêm trọng của đời mày đang điểm. Bây giờ hoặc là

không có bao giờ nữa. Mày phải cương quyết. Không có thứ nhân đạo nào cấm

mày không được tàn nhẫn ngay với mày. Mày hãy diệt hết những con người cũ

ở trong mày đi – những con người mà mày mệnh danh là cố nhân, theo một cái

cố tật ưa du dương với kỷ niệm. Đào thải, chưa đủ. Phải tàn sát. Giết, giết

hết. Thò đứa nào ở dĩ vãng hiện về đòi hỏi bất cứ một tí gì của mày bây giờ,

là mày phải giết ngay. Mày phải tự hoại nội tâm của mày đi đã. Mà hãy lấy

mày ra làm lửa mà đốt cháy hết những phong cảnh cũ của tâm tưởng mày”… Chàng

chạy ra đường. Ngoài đường, cuộc Cách Mệnh đang bước dài trên khắp ngả phố.

Trên các cửa sổ mở, gió đời lùa cờ máu bay theo một chiều… Nguyễn thấy mệt

mỏi trong lòng và trên thân chàng thì xót nhức vô cùng. Thì ra, lúc ở nhà

ra đi, chàng vừa chịu xong một cái nhục hình. Lý trí đã lột hết lượt da trên

mình Nguyễn… Cái luồng gió ban nãy thổi cờ máu, thổi mãi vào thịt non Nguyễn

đang se dần lại. Nguyễn thèm đến một con rắn mỗi năm thoát xác một lần…

Trích “Lột Xác”, của Nguyễn Tuân, in trong tuyển tập Nguyễn Tuân,

tập I, nhà xuất bản Văn Học, Hà Nội, ấn bản năm 2000.

Từ "cờ máu", là của Nguyễn Tuân, không phải của lũ Ngụy.

Tiếng chim khua vỡ buổi sáng lạnh

http://giaitri.vnexpress.net/tin-tuc/sach/lang-van/phan-huyen-thu-khang-dinh-viet-bai-tho-gay-tranh-cai-19-nam-truoc-3298707-p3.html

Những ai buộc tội PHT đạo thơ, trong hai trường hợp đang được nhắc

tới, theo Gấu, đều chưa từng làm thơ, hoặc chỉ làm thứ thơ nhì nhằng, bởi

là vì 1 người mà làm nổi 1 câu thơ “được trao cho thi sĩ”, theo ý của Borges,

không thèm đạo thơ của bất cứ ai, vì, làm sao hay hơn, của chính ta đây?

Rõ như ban ngày.

Cả bai bài thơ, từ chìa khoá của chúng, là khua, khuấy, blues, buổi

sáng, đều từ… thơ TTT, nhớ 1 câu, sáng mai “khua” thức nhiều nhớ thương,

bị lầm thành “khuya” thức.

Từ trái, các ca sĩ Quỳnh Giao,

Mai Hương, Thái Thanh.

WESTMINSTER

(VB) -- Hơn 120 người đã dự buổi Tưởng Niệm Thanh Tâm Tuyền đêm Thứ Năm

30-3-2006 tại Phòng Sinh Hoạt Nhật Báo Việt Báo.

Ca sĩ Lệ Thu được mời hát bài Dạ Tâm Khúc, một bản nhạc được Phạm

Đình Chương phổ từ thơ Thanh Tâm Tuyền.

Chị kể thời còn ở Sài Gòn, cứ hát nhầm, “đưa em vào quán rượu” thành

“đưa em vào quán trọ” và một lần được nhà thơ ghé tai vừa chỉnh vừa đùa...

Thanh Tâm Tuyền cũng đã từng kể, về một câu thơ của ông "sáng mai khua thức nhiều nhớ thương", bị ông thợ

nhà in sửa thành "sáng mai khuya

thức..."

Gấu nhắc tới “ông anh của mình”, ở đây, là để cho thấy, có khi, bạn

“ảnh hưởng” [đạo] mà không biết mình, đạo.

Trên TV có kể về giai thoại thú vị liên quan tới nhà thơ Beckett.

Nhưng tuyệt nhất, là bài viết của Borges, về những vị thầy [tiền thân,

người đi trước], precursors, của Kafka.

Bản thân Gấu, thuổng Borges, khi viết về cuốn Bếp Lửa của TTT, vào

năm 1972, chỉ đến khi ra hải ngoại, thì mới biết, của ông.

Hay là bài viết về “ảnh hưởng” của Rushdie, cũng đã đăng trên Tin

Văn.

Trường hợp Sến, trên talawas, ra lệnh cho 1 tên Cớm văn học đánh PHT,

khi bà này làm cái poster TTT, trong ngày hội thơ ở Văn Miếu, ngay khi

đó, Gấu đã chỉ ra, những gì PHT đạo, chỉ là những information, tài liệu,

có sẵn trên báo chí. Ăn cắp cái gì, khi chúng sờ sờ ra đấy. Một khi xb thành

sách, thí dụ, nếu cần, thì để vô phần tiểu chú.

Một việc làm ý nghĩa như thế, mà cũng bị 1 lũ nhơ bẩn xúm vào đánh.

Chuyện đang xẩy ra bây giờ thì cũng vậy.

Ganh ăn, ghen tài…. thế là xúm lại, đâu có khác gì mấy cái clip video

You tube, cho thấy cái sự dã man của giống Mít.

…. Giữa đông, giữa năm 1973, lạnh cứng người, cô đơn, túi thủng, tôi

đành phải làm cái trò đọc thơ, vào lúc tám giờ tối, tại Trung Tâm Văn Hóa

Mỹ ở con phố Dragon.... với cái giá năm chục đô. Tôi có cái uống với Beckett

vào lúc bẩy giờ. Tôi đâu dám xì ra cái chuyện đọc thơ, bởi vì, tôi nghĩ

ông chẳng ưa cái chuyện đọc thơ trước công chúng, cho dù phải cạp đất, và

ông gần như chẳng bao giờ làm chuyện đó.

Trong lúc cà kê, ông có vẻ đâu đâu. Dưng không, ông nói: "Bạn đọc

thơ, phải không?" Tôi chới với, làm sao ông biết? Rồi ông thêm: "Chắc mong

bạn bè tới đông, hẻ?". Hiển nhiên, tôi làm ông đau, khi không mời. Vậy

là tôi đã làm ông đau, bực thiệt! Ông nói, như cho tôi đỡ đau: "Không,

cám ơn bạn, tôi không bao giờ tới với những chuyện đó".

Rồi thì ông yêu cầu tôi đọc một bài thơ, của tôi, cho ông nghe. Nhột

quá, tôi bảo ông, cái giá năm mươi đô là ổn, đối với tôi. Ông bật cười,

tuy nhiên vẫn bắt tôi đọc thơ cho bằng được. Thơ đọc thầm lén mà!

Thế là tôi ư ử, bài "Trên Đại Lộ Raspail":

How easily our only smile smiles.

We will never agree or disagree.

The pretty girl is perfected in her passing.

Our love lives within the space of a quietly closing door

Ông chăm chú nghe, mắt nhắm tít. "Được! Được!", ông nói.

"Ồ, c...! " Tôi bật lên. Ông mở choàng mắt, và tôi tự giải thích:

"Tớ ăn cắp của bạn!"

"Không, không. Tôi chưa hề nghe nó trong đời..."

"Không, không, của bạn! Bài 'Dieppe'..., bạn chấm dứt với 'the space

of a door that opens and shuts'

"Ô! Đúng thế thực." Nhưng rồi, bỗng nhiên, ông thêm vô: "Ô, c...!"

"Chuyện gì nữa, hả?", tôi hỏi.

"Tôi chôm của Dante, chính tôi!

Tiền Thân Kafka

Trầm

luân vì niềm tin

Note: Cuốn Đêm Giữa Ban Ngày của Koestler đúng

là 1 thứ vắc xin đối với Gấu, những ngày mới lớn, và không chỉ Gấu, mà cả

Âu Châu. Không có nó, và “1984” của Orwell, là Xì nhuộm đỏ cả thế giới rồi!

Koestler

Raging towards Utopia

Điểm Sách

London đọc tiểu sử Koestler của

Scammell

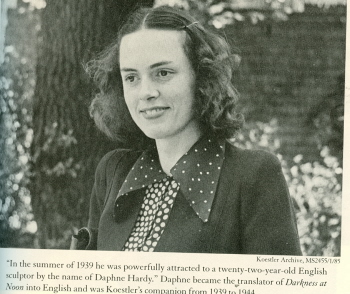

Em này là

tác giả cái tít cuốn sách của VTH: Đêm giữa ban ngày!

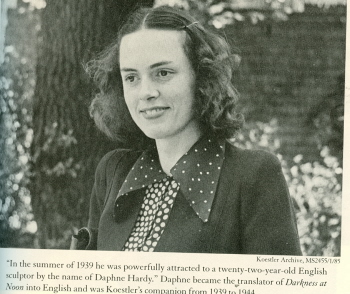

Cái tít Đêm giữa Ngọ, như trong cuốn tiểu sử K của Scammell cho biết,

K. nghĩ rằng, được trích dẫn từ Samson Agonistes của Milton: “Oh dark, dark,

dark, amid the blaze of noon”. Thực sự, Daphne được gợi hứng từ Sách của [Book of] Job: “They meet with darkness in the daytime,

and grope in the noonday as in the night” [Job 5:14]

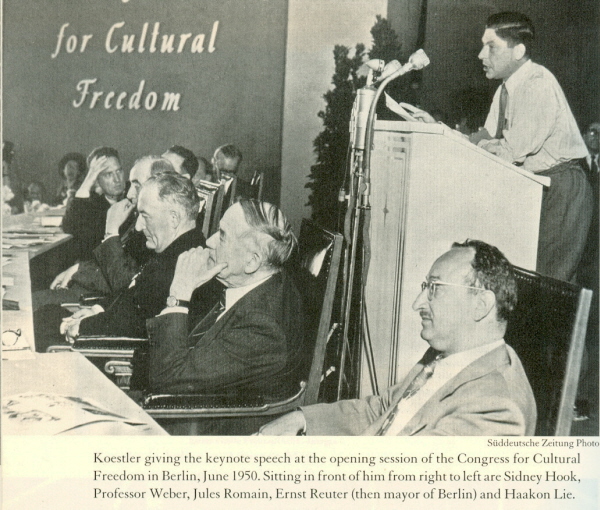

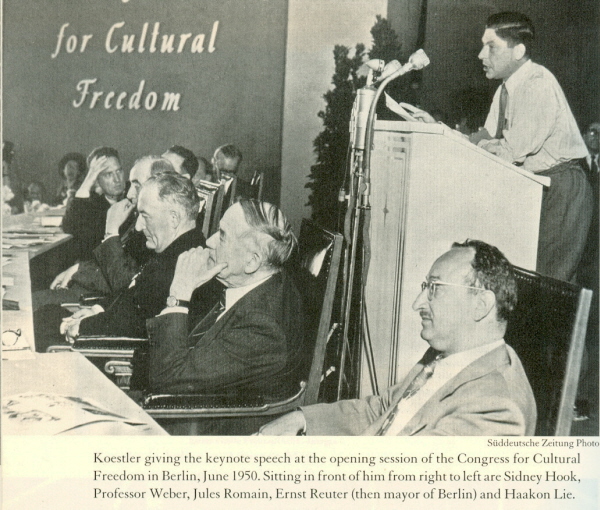

K. mở ra ‘cái gọi là’ Mặt

trận bảo vệ văn hóa tự do, với anh Hai chi địa, là Xịa. ST có là nhờ nó.

Chương trình WJC chắc cũng từ đó.

[Từ đó trong tôi bừng nắng hạ!] Bộ sách vĩ đại Văn Học Miền Nam của

VP chắc cũng là từ đó! Lẽ dĩ nhiên, dưới những cái tên chi địa khác! Rockefeller

Foundation, thí dụ. Nhưng đều là đô la Mẽo cả!

*

“My analysis of Koestler is: one third genius, one third blackguard,

and one third lunatic”, [Tôi nhận xét K. 1/3 thiên tài, 1/3 đê tiện, và

1/3 khủng, mát] tay cảnh sát chìm giả làm tù nhân bị nhốt cùng phòng với

K, tại nhà tù Pentonville, báo cáo với sếp.

(1) Mới dinh cuốn Bóng Đêm từ một tiệm sách cũ về, cùng

với cuốn Bộ lạc thứ 13:

The Thirteenth Tribe, written near the end of his life, attempted to

prove that Ashkenazi Jews - the main body of European Jewry - were not

ethnic Jews at all but the descendants of the Khazars, Turkic nomads from

Asia who had converted to Judaism

in the eighth century. To the dismay of most Jews, the book was a huge

success and is still quoted with delight by Israel's

hostile neighbors.

Neal Ascherson: Raging towards Utopia

Gấu đọc lại

Đêm giữa Ngọ, để kiểm tra trí nhớ, và để sống lại những ngày mới vô Sài

Gòn.

Quả có mấy

xen, thí dụ, Ông số 2 đang đêm bị hai chú công an đến tóm, và ông ra lệnh

cho chú công an trẻ măng, cách mạng 30 Tháng Tư, lấy cho tao cái áo đại

quân thay vì đứng xớ rớ mân mê khẩu súng! Có cái xen ông số 2 dí mẩu thuốc

đỏ hỏn vô lòng bàn tay, và tưởng tượng ra cái cảnh mình đang được đám đệ

tử tra tấn. Có câu chuyện thê lương về anh chàng ‘Rip của Koestler’ [Giá mà

Bác Hồ hồi đó, khi ở Paris,

đọc được, thì chắc là hết dám sáng tác Giấc Ngủ 10 năm, có khi còn từ

bỏ Đảng cũng nên!]

Thà chơi bửn mà thắng, còn hơn chơi đẹp mà thua!

Trong lúc rảnh rỗi, tôi viết một cuốn

tiểu thuyết Tới và Đi, Arrival and Departure, và một số tiểu luận,

sau được đưa vô The Yogi and the Commissar [Du Già và Chính Uỷ]

Tới và Đi là tập thứ ba, trong một bộ ba tập,

trilogy, trong đó, đề tài trung tâm của nó là cuộc xung đột giữa đạo đức

và thiết thực [expediency: miễn sao có lợi, thủ đoạn, động cơ cá nhân –

khi nào, hoặc tới mức độ nào, thì một cứu cánh phong nhã [vẫn còn có thể]

biện minh cho một phương tiện dơ bẩn. Đúng là một đề tài Xưa như Diễm, nhưng

nó ám ảnh tôi suốt những năm là một đảng viên CS .

Tập đầu của bộ ba, là Những tên giác

đấu, The Gladiators, kể cuộc cách mạng [revolution] của những nô

lệ La mã, 73-71 BC, cầm đầu bởi Spartacus, xém một tí là thành công, và cái

lý do chính của sự thất bại, là, Spartacus đã thiếu quyết định [lack of determination]

– ông từ chối áp dụng luật quay đầu, trở ngược, “law of detours”; luật này

đòi hỏi, trên con đường đi tới Không Tưởng, người lãnh đạo phải “không thương

hại nhân danh thương hại”, ‘pitiless for the sake of pity’. Nôm na là, ông

từ chối xử tử những kẻ ly khai và những tên gây rối, không áp dụng luật

khủng bố - và, do từ chối áp dụng luật này khiến cho cuộc cách mạng thất

bại.

Trong Bóng

đêm giữa ban ngày, tay cựu truởng lão VC Liên Xô Rubashov đi ngược

lại, nghĩa là, ông theo đúng luật trở ngược đến tận cùng cay đắng - chỉ

để khám phá ra rằng ‘lô gíc không thôi, là một cái la bàn không hoàn hảo,

nó sẽ đưa con người vào một chuyến đi đầy dông bão, cuối cùng bến tới biến

mất trong đám sương mù.’

Hai cuốn, cuốn nọ bổ túc cho cuốn kia, và cả hai đều tận cùng bằng

tuyệt lộ.

Tribute to Koestler

In the next

TLS

Jeremy Treglown:

Whoever reads Arthur Koestler now?

Ai còn đọc K. bây giờ?

Có tớ, đây!

Bây giờ gần như mọi người đều quên ông [Koestler], nhưng đã có thời,

tất cả những sinh viên với tí mầm bất bình thế giới, họ đọc ông. Những

sinh viên, đám cháu chít của họ, hay đám trí thức “của” ngày mai, họ chẳng

hề nghe nói đến ông. Một số nhà phê bình nghĩ, sự lãng quên này thì là