Prague của

Kafka

|

Kafka's

Prague Prague isn't willing to

leave nor

will it let us leave. This girl has claws and people must line up or we

will

have to light a fire at Vysehrad and the Old Town Square before we can

possibly

depart. -Excerpt from a letter from Kafka to Oskar Pollak Xề Gòn đếch

muốn bỏ đi, mà cũng đếch muốn GCC bỏ đi. Trong bài viết

của Bei Dao, trên, có nhắc tới cuốn sau đây.

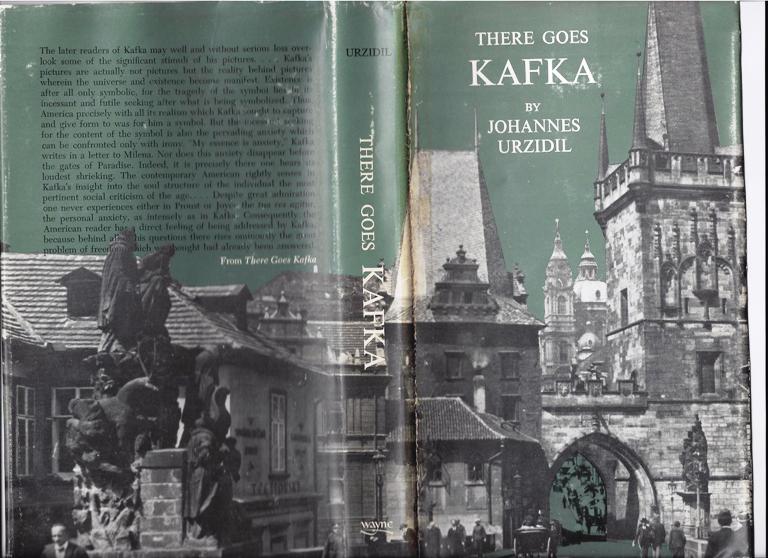

Kafka,

hàng độc "Kafka

was Prague and Prague was Kafka.

It had never been so completely and so typically Prague, nor would it

ever again

be so as it was during Kafka's lifetime. And we, his friends ... knew

that this

Prague permeated all of Kafka's writings in the most refined miniscule

quantities." From an intimacy with a common spiritual homeland shared

with

Kafka, Professor Johannes Urzidil conjures up the essential background

of the

poet and provides authentic emphases for the understanding of his

literary art.

Personal experiences and recollections, wide reading, penetrating

insight, and

love congeal in Urzidil into an authentic and convincing interpretation

of the

living atmosphere surrounding Kafka and of his prime literary motifs

and ideas.

This edition, like that of the Deutsche Taschenbuch Verlag, has been

enlarged

so as to include five hitherto unpublished chapters, viz., impressive

portraits

of people close to Kafka, commentaries on Kafka's relation to the

visual arts,

on the history and impact of the Colem myths, on Kafka's intent at one

time to

destroy his manuscripts, as well as Urzidil's speech at the

commemorative

observance in 1924 in the Little Theater in Prague shortly after

Kafka's death. Professor Johannes Urzidil

was born in 1896 in Prague. After completing his philosophical

studies there, he became one of the younger poets of the German

expressionist movement

and was in close contact with the Prague Literary Circle of Brod,

Kafka, Werfel,

and others. In 1939 he emigrated to the United States via Italy and

England and

settled in New York, where he is still living. His first publication

was a

volume of expressionistic poems (1919). Professor Urzidil has published

seven

volumes of stories and novels and is the author of many essays and

treatises.

Among his better known and more important scholarly works are Goethe in

Bohmen

(Goethe in Bohemia), 1962; Goethes Amerikabild (Goethe's Image of

America),

1958; and Amerika und die Antike (America and Ancient Antiquity)1964.

He was

awarded the Swiss International Prix Veillon for the best German novel

(1957),

the literary prize of the City of Cologne (1964), the Great Austrian

State Prize

for Literature (1964), and the Andreas Gryphius Prize (1966). He is a

corresponding

member of the German Academy of Language and Poetry in Darmstadt, of

the Austrian

Adalbert Stifter Institute and of several other learned and literary

societies.

Works of Johannes Urzidil have been translated from the German

originals into

English, French, Italian, Czech, Dutch, Hungarian, Russian, and Spanish. jacket design by S. R. Tenenbaum

Sài Gòn là Gấu,

và Gấu là Sài Gòn. Sài Gòn sẽ chẳng bao giờ hoàn tất đến như thế, đặc

biệt Sài

Gòn đến như vậy, và nó sẽ chẳng bao giờ lại như vậy, như trong đời của

Gấu,

khi ở Sài Gòn! Cái “Sài Gòn

là Gấu và Gấu là Sài Gòn”, áp dụng chung cho tất cả chúng ta, Miền Nam,

và nó là 1

chân lý, bị cố tình hiểu lầm ra là, toan tính phục hồi cái xác chết

VNCH. Cái "gì gì" lịch sử có thể viết lại nhưng không thể làm lại! [Châm ngôn lừng danh của SCN] (1)

A Different

Kafka

Note: Tay này, John

Banville , nhà

văn số 1, phê bình, điểm sách cũng số 1.

Thử đếm coi,

Thầy Kuốc điểm sách của ai, khui ra được nhà văn nào. Mũi lõ cũng

không, mà mũi

tẹt lại càng không? GCC ư? Nhiều

lắm. Bảo Ninh, thí dụ, Gấu phát

giác ra, ở hải ngoại, và cái ông BN mà

Gấu viết,

cũng khác ông ở trong nước. Miêng, Mai Ninh, Trần

Thanh Hà, Trần Thị NgH... Gấu đều trân trọng viết

về họ.

Of course,

Kafka is not the first writer, nor will he be the last, to figure

himself as a

martyr to his art—think of Flaubert, think of Joyce—but he is

remarkable for

the single-mindedness with which he conceived of his role. Who else

could have

invented the torture machine at the center of his frightful story “In

the Penal

Colony,” which executes miscreants by graving their sentence—le

mot juste!—with a metal stylus into

their very flesh? Lẽ dĩ nhiên,

Kafka đâu phải nhà văn đầu tiên, càng không phải nhà văn cuối cùng,

nhìn ra

mình, lọc mình ra, như là 1 kẻ tuẫn nạn, vì cái thứ nghệ thuật mà mình

chọn lựa

cho mình: “dziếc dzăng”! “Kim chích vô

thịt thì đau” là theo nghĩa này đấy! [Note: Trang TV này cũng đang hot, nhờ vậy mà GCC mới biết đến nó]

Primo Levi

phán, tớ là 1 nhà hóa học, tớ quan sát, để hiểu, nhưng hiểu không có

nghĩa là

tha thứ, bởi là vì tha thứ là hành động chỉ có những người có niềm tin

tôn

giáo, làm được. Một tên vô thần như tớ, thua! "Comprendre,

ce n’est pas pardoner". Le pardon est un acte religieux don’t il est,

lui

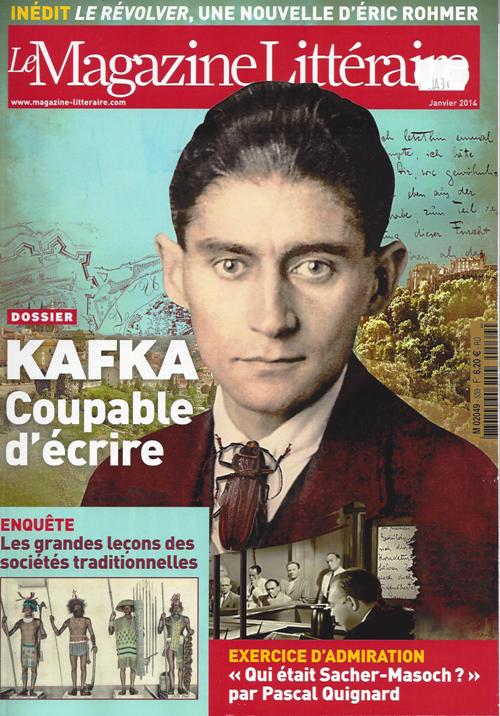

l’athée, incapable. Trong số báo mới nhất về Kafka, có hai bài, lạ, một, về Kertesz và mối nối giữa ông và Kafka, và một, về Primo Levi, đúng hơn, về 1 cuộc trò chuyện của ông, Vùng Xám, La Zone Grise, mới ra lò. Bài “Ba cái nhìn để biến Kafka thành 1 kẻ vô xứ” [từ này Gấu chôm của Thầy Đạo], “Trois regards pour dépayser Kafka”, trong ba cái nhìn này, thì cái nhìn biến Kafka thành nhà thơ của sự tủi hổ và phạm tội, khủng nhất.

Kafka đi vô truyền thuyết

"Sát Thủ Đầu Mưng Mủ"!

[Books, Janvier, 2014]

Dịch lại & Lại dịch

"Hóa Thân" của Kafka qua tiếng Anh JANUARY

15, 2014 ON

TRANSLATING KAFKA’S “THE METAMORPHOSIS” POSTED

BY SUSAN BERNOFSKY This essay is adapted from the afterword to the author’s new translation of “The Metamorphosis,” by Franz Kafka. Cú

khó sau chót, về dịch, là cái từ trong cái tít. Không

giống từ tiếng Anh, “metamorphosis,”

“hóa

thân”, từ tiếng Đức

Verwandlung

không đề nghị cách hiểu tự nhiên, tằm

nhả tơ xong, chui vô kén, biến thành nhộng, nhộng biến thành

bướm, trong vương quốc loài vật. Thay vì

vậy, đây là 1 từ, từ chuyện thần tiên, dùng để tả sự chuyển hóa, thí dụ

như

trong chuyện cổ tích về 1 cô gái đành phải giả câm để cứu mấy người

anh bị bà phù thuỷ biến thành vịt, mà Simone Weil đã từng đi 1 đường

chú giải

tuyệt vời. Hà,

hà! One

last translation problem in the story is the

title itself. Unlike the English “metamorphosis,” the German word Verwandlung

does not suggest a natural change of state associated

with the animal

kingdom such as the change from caterpillar to butterfly. Instead it is

a word

from fairy tales used to describe the transformation, say, of a girl’s

seven

brothers into swans. But the word “metamorphosis” refers to this, too;

its

first definition in the Oxford English Dictionary is “The action or

process of

changing in form, shape, or substance; esp. transformation by

supernatural

means.” This is the sense in which it’s used, for instance, in

translations of

Ovid. As a title for this rich, complex story, it strikes me as the

most

luminous, suggestive choice.

|