|

Tưởng

niệm Camus, 50 năm sau

khi ông mất

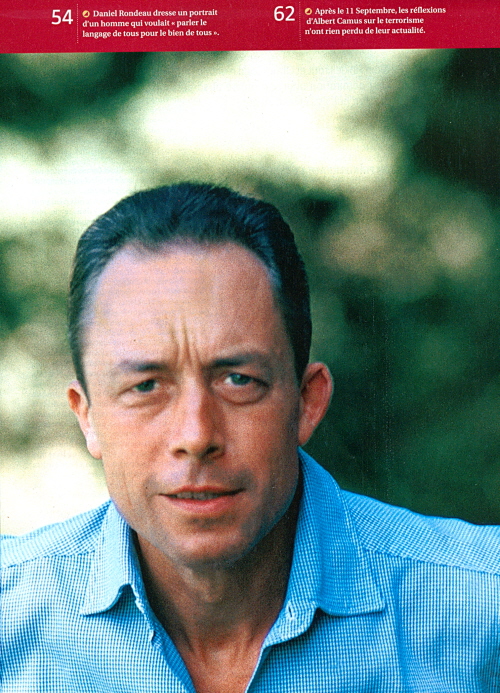

Albert

Camus, à la fin des

années 1950.

Một trái tim Hy Lạp

Un coeur grec

*

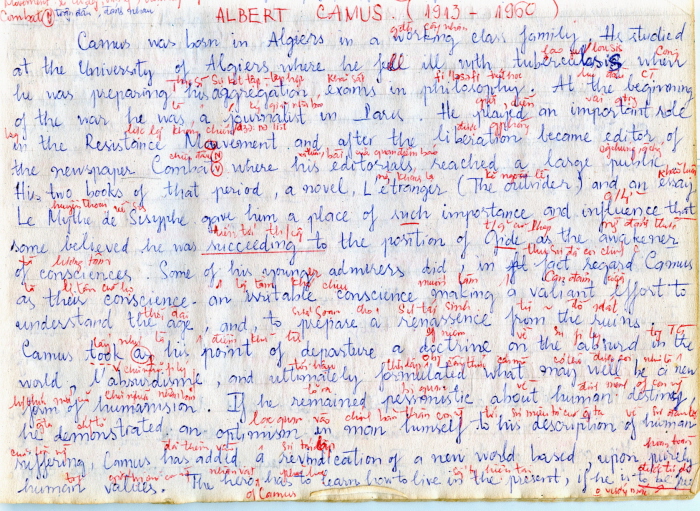

Albert Camus

penser la

révolte

Que reste-t-il aujourd'hui de

la pensée d'Albert Camus?

Deux récents volumes de la

Pléiade, qui présentent ses écrits en suivant l'ordre chronologique,

nous font

redécouvrir pas à pas l'itinéraire d'un intellectuel engagé à qui

l'Histoire a

donné raison, tant dans son combat contre les totalitarismes que dans

sa

querelle avec Sartre. La vérité, qu'elle soit de droite ou de gauche,

voilà

tout ce qui comptait pour ce « Français d'Algérie» né dans la misère,

cet

amouureux du soleil qui avait à cœur de célébrer la beauté du monde

sans jamais

en négliger la part d'ombre. Loin des étiquettes habituelles et souvent

réductrices (l'écrivain de l'absurde, le moraliste bien-pensant, le «

philosophe pour classes terminales »), Albert Camus, en choisissant

l'homme plutôt

que son concept et en liant révolte et mesure pour dénoncer la

tentation

nihiliste de la révoluution pure, a fait montre d'une audace inégalée.

Entre

exigence d'équilibre et sentiment du tragique, combativité et

scepticisme,

Albert Camus n'a jamais perdu le sens de la nuance, quelles que soient

les

tempêtes politiques qui l'environnaient. Son combat contre toute forme

d'extrémisme,

qui trouve une de ses plus belles expressions dans sa réflexion sur le

terrorisme, nous invite plus que jamais à relire une œuvre placée sous

le signe

de « la gratitude au monde ».

Dossier coordonné par Minh

Tran Huy

Tuyệt!

Le Magazine Littéraire Mai

2006

số đặc biệt về Camus

*

The Mandarin

Of all

the writers of my

time, there were two that I preferred above all others and to whom I

was most

indebted in my youth. One of them, William Faulkner, was well chosen

for he is

an author that any aspirant novelist should read. He is perhaps the

only contemporary

novelist whose work can be compared, in volume and in quality, with the

great

classics. The other, Sartre, was less well chosen: it is unlikely that

his

creative work will last and although he had a prodigious intelligence

and was,

on balance, an honest intellectual, his ideas and his position on

issues were

more often wrong than right. Of him we can say what Josep Pla said of

Marcuse:

that he contributed, with more talent than anyone else, to the

confusion of our

times.

Mario Vargas Losa

Trong

tất cả những nhà văn của

thời của tôi, có hai đấng mà tôi mê nhất, mang nợ

nhiều nhất,

vào thời trẻ.

Một, William Faulkner, chọn đúng

bong, quá bảnh, bởi ông là một tác giả mà bất cứ thằng chó nào lăm le

viết văn,

viết tửu thiết, cũng nên đọc! Ông có lẽ là tiểu thuyết gia đương thời

độc nhất

mà tác phẩm có thể so sánh, về bề dầy cũng như phẩm chất, với những

đấng sư

phụ cổ điển nhớn nhao, vĩ đại.

Một, Sartre, chọn lựa không

khấm khá: có vẻ như tác phẩm mang tính sáng tác của ông không trường

thọ, mặc dù ông thông minh có thừa, và ông, nếu có nói đi thì phải nói

lại,

là một tay trung thực, lương thiện, những tư tưởng và vị trí của ông,

thì trật

nhiều hơn trúng.

Về Sartre, chúng ta có thể lấy

câu của Josep Pla, nói về Marcuse, để nói về ông, trúng ngay bong:

Bằng tài năng Sartre đóng góp,

nhiều hơn bất cứ một ai, vào cái phần, làm nhiễu nhương thêm, cho thời

của chúng

ta!

Tuyệt!

Llosa: Quan Sartre [The

Mandarin]

Vậy mà

có thằng ngu mắng Gấu,

sao cứ lải nhải hoài về Faulkner!

Trong số những đệ tử của ông,

Gấu mới đúng thứ chân truyền, bởi vì không một ai khác, đau

cùng với ông nỗi đau “Yankee [mũi tẹt] hãy cút cha mày đi!”

Hà, hà!

Camus

trên đường đi Stockholm

lãnh Nobel.

Faulkner gửi cho‘bạn quí’một

cái mail:

‘Chúc mừng một tâm hồn luôn

tìm kiếm và tra hỏi’

*

Albert Camus

penser la révolte

Que reste-t-il aujourd'hui de

la pensée d'Albert Camus?

Deux récents volumes de la

Pléiade, qui présentent ses écrits en suivant l'ordre chronologique,

nous font

redécouvrir pas à pas l'itinéraire d'un intellectuel engagé à qui

l'Histoire a

donné raison, tant dans son combat contre les totalitarismes que dans

sa

querelle avec Sartre. La vérité, qu'elle soit de droite ou de gauche,

voilà

tout ce qui comptait pour ce « Français d'Algérie» né dans la misère,

cet

amouureux du soleil qui avait à cœur de célébrer la beauté du monde

sans jamais

en négliger la part d'ombre. Loin des étiquettes habituelles et souvent

réductrices (l'écrivain de l'absurde, le moraliste bien-pensant, le «

philosophe pour classes terminales »), Albert Camus, en choisissant

l'homme plutôt

que son concept et en liant révolte et mesure pour dénoncer la

tentation

nihiliste de la révoluution pure, a fait montre d'une audace inégalée.

Entre

exigence d'équilibre et sentiment du tragique, combativité et

scepticisme,

Albert Camus n'a jamais perdu le sens de la nuance, quelles que soient

les

tempêtes politiques qui l'environnaient. Son combat contre toute forme

d'extrémisme,

qui trouve une de ses plus belles expressions dans sa réflexion sur le

terrorisme, nous invite plus que jamais à relire une œuvre placée sous

le signe

de « la gratitude au monde ».

Dossier coordonné par Minh

Tran Huy

Bây giờ, tư tưởng

Camus còn tí

gì? Hai cuốn mới ra lò, tủ sách Pléiade, trình bầy suy nghĩ của ông

theo dòng

biên niên, làm chúng ta lại khám phá từng bước đi, hành trình của

một nhà trí thức nhập cuộc, và Lịch Sử, đã cho thấy là ông ta có lý,

trong cuộc

chiến của ông, chống lại những chế độ toàn trị, cũng như trong vụ lèm

bèm với

Sartre. Sự thực, cho dù tả hay hữu, đó là tất cả những gì mà ông quan

tâm, cái ông

'Tây gốc thuộc địa Algérie' sinh ra từ nghèo đói, khốn cùng,

kẻ mê mẩn

ánh nắng, ‘mặt trời chân lý chói qua tim’, nhưng chẳng bao giờ quên

phần

bóng tối

của nó.

Hãy vất mẹ mọi cái nón mà đám người thiển cận thường chụp cho

ông, (nhà

văn của phi lý, nhà đạo đức lẩm cẩm, triết gia của học sinh trung học,

những năm

chót), Albert Camus, trong khi chọn con người thay vì cái quan niệm về

nó, và

trong khi nối kết sự phản kháng và chừng mực, để tố cáo sự cám dỗ hư vô

của cách

mạng thuần tuý, đã cho thấy một sự can đảm cùng mình.

Giữa đòi hỏi, về

một sự cân

bằng và cảm tính bi đát, chiến đấu và bi quan, Albert Camus chưa bao

giờ để mất

đi bản lĩnh, sắc thái của mình, mặc dù bão tố chính trị vây quanh ông.

Cuộc chiến

đấu của ông chống lại mọi hình thức cực đoan, đã tìm thấy những biểu

hiện tuyệt

vời, ở trong sự suy nghĩ của ông về chủ nghĩa khủng bố, và, hơn lúc nào

hết, vào

lúc này, nó mời gọi chúng ta đọc lại một tác phẩm, đặt dưới dấu hiệu

của ‘la

gratitude au monde’ [biết ơn thế giới]

Trần

Minh Huy, người điều

nghiên, bố trí, phân bổ công tác viết lách cho số đặc biệt về Camus,

Le Magazine Littéraire Mai 2006

Cái

thái độ không khoái

Camus, như của TTT, thí dụ, là rất phổ biến trong giới trí thức, dân

viết lách,

trên toàn thế giới, quái thế!

Nhưng dần dà, người ta càng

thấm đòn của Camus, nhất là sau cú 911.

Olivier Todd, vốn được coi là ‘đứa con trai

nổi loạn’ của Sartre, rất thân cận với đám ‘sartriens’ [những người của

Sartre], những năm 1950, 1960, vào lúc đó, Camus chưa tỏa ra 'mùi

thánh' [en odeur de la sainteté]. Dần dần ông tò tò theo Camus, và tới

năm 1997,

cho ra lò “Camus, một đời người”, một

cuốn tiểu sử thật đẹp, dưới dạng tưởng

niệm mang tính phê bình, được coi là một cuốn từ điển, une référence,

về Camus.

Trong số báo đặc biệt biệt về

Camus, đã dẫn, có cuộc trò chuyện, Một

sự đọc lại Albert Camus, giữa Todd và Alain

Finkielkraut [tiểu luận gia, đệ tử Levinas, tác giả Sự

thất bại của tư tưởng, 1987, một cuốn sách nổi cộm, gây rất nhiều

tiếng ồn, người tìm thấy ở Camus rất nhiều đồng điệu…]

Lý do nào hai ông đếch chịu được Kẻ Xa Lạ?

Olivier Todd: Hãy

hỏi đám

sinh viên nước ngoài. Đánh chết, thì anh nào cô nấy đều chọn Kẻ Xa Lạ, cuốn sách gối đầu giường! Vì

những lý do tốt, và.. xấu.

Tốt: Một cuốn sách rất uyên

nguyên, original, bí ẩn, mystérieux, thật khó cắt nghĩa.

Xấu: Nó ngắn quá, cụt thun lủn!

Alain Finkielkraut có cái may

là chỉ biết Camus qua tác phẩm: tôi nghĩ, tôi bị Camus mà mắt, là do vụ

chủ nghĩa

CS và Bắc Phi, và do ảnh hưởng của đám sartriens. Nhưng tôi không bao

giờ mê nổi La Peste, Dịch Hạch, mặc dù lần đầu đọc,

thấy ‘sáng và mạnh’ [lumineux et fort]: Rổn rảng quá, những kẻ tốt,

những người

xấu…

Tôi cũng không chịu được cách

giải thích của Edward Said, ông ta cho rằng, Camus chẳng bao giờ đưa

được một

anh Ả Rập nào ra hồn [crédible] vào trong cuốn sách đó: ông ta có biết

thằng chó

nào đâu! [il ne les connaissait pas!]

*

Le Magazine Littéraire:

Albert Camus là một khuôn mặt

trí thức nổi cộm trong đời sống tinh thần của nước Tẩy… Ngoài ra còn là

một nhân

vật, một huyền tượng…

Olivier Todd: Tôi mất năm năm

với thằng chả, để viết cuốn tiểu sử về hắn ta. Trong đời thường, cũng

cay

đắng ngọt bùi lắm [sucrées-salées: đường ngọt, muối mặn]. Một bữa, vào

những năm

1950, tôi đang ngồi Cà phê Marie, chỗ quảng trường Saint-Sulpice, với

bà vợ tuyệt

trẻ của tôi [avec ma très jeune femme]. Camus tới, ngồi ở quầy, và nhìn

bả như

muốn lột trần truồng bả ra, [qui n’arrête pas de la déshabiller des

yeux.] Tôi tức

điên lên…

Alain Finkielkraut: Tức điên,

hay sướng điên lên? [Furieux ou flatté?]

Albert

Camus, gardien de but

au Racing Universitaire d'Alger, vers 1930.

« Ce que, finalement,

je sais

de plus en plus sur

la morale et les obligations des hommes, c'est au sport que je le dois.

»

"Điều mà sau cùng tôi biết ngày một nhiều, về đạo đức và những đòi hỏi

ở nơi con người, thì là nhờ thể thao mà tôi có được"

Cứ mỗi mùa thi

đấu quốc tế là lặp đi lặp lại hiện tượng những dòng người cuồng mê đổ

ra đường

mừng chiến thắng bóng đá, rồi lồng ghép tinh thần yêu nước, hội chứng

yêu nước

kiểu đó là điều ngớ ngẩn. Nếu muốn chứng minh phẩm chất Việt Nam,

hãy hướng đến những nội dung xã hội toàn diện hơn và nhất là chứng minh

sự vượt

trội của tinh thần quốc gia - dân tộc trong những giá trị văn minh và

nhân

quyền.

Trần Tiến Dũng

BBC

Đây không phải chuyện ngớ ngẩn!

Cơn cuồng si bóng đá có liên

quan đến chiến thắng 30 Tháng Tư, 1975.

Thế mới quái!

Gấu sẽ giải thích tiếp, sau.

*

Mới đây, đọc Mario

Vargas

Llosa, nhà văn Peru, bài viết World

Cup, Spain 1982 (trong Making

Waves, Penguin

Books), ông có nhắc tới nhà văn người Pháp Albert Camus, theo đó, những

bài học

đạo hạnh đẹp nhất mà Camus học được, không phải ở trong những căn phòng

đại

học, nhưng mà là ở trên sân cỏ.

Mở ra bằng một nhận

định đẹp

như thế, tuy nhiên bài viết lại có cái nhan đề thật đúng ý Fowles, nhà

văn gốc

Hồng Mao, nơi phát sinh ra môn bóng đá: Trước cuộc truy hoan (Before

the orgy).

Trong bài viết, tác giả cũng đưa ra một vài ẩn dụ rất ư là bực mình, và

cũng

thật đáng quan ngại, về bóng đá, mà ông bảo là, của một người bạn của

ông:

Khung thành là một cái âm hộ qua đó, một cầu thủ, một đội banh, một sân

đất,

một xứ sở, cả nhân loại, "bất thình lình xả hết sinh lực tạo giống của

‘chúng mình’ vào đó."

Như trên đã viết, bạn

không

thể và không muốn ở giữa. Khi trái banh vừa mới lăn, là bạn đã chọn

bên. Và khi

nghe ông Huyền Vũ, chuyên viên bình luận bóng đá trên đài phát thanh

Sài Gòn

ngày nào reo như muốn vỡ cái la dô: Màng trinh đội bạn đã bị thủng!,

thì bất cứ

một ai trong chúng ta đều cảm thấy, một cách hãnh diện, và cũng thật

đầy nam

tính (hay Việt tính?): Chính tớ đã làm cú đó đó!

Bởi vì theo Llosa, mọi xứ sở

đều chơi bóng đá, đúng cái kiểu mà họ làm tình. Những mánh lới, kỹ

thuật này nọ

của những cầu thủ, nơi sân banh, đâu có khác chi một sự chuyển dịch

(translation)

vào trong môn chơi bóng đá, những trò yêu đương quái dị, khác thường,

khác các

giống dân khác, và những tập tục ân ái từ thuở "Hùng Vương lập nước"-

thì cứ thí dụ vậy - lưu truyền từ đời này qua đời khác tới tận chúng ta

bi giờ!

Ông đưa ra thí dụ: Những cầu thủ Brazil mân mê trái banh

thay vì đá

nó. Anh ta không muốn rời nó ra, và thay vì đá trái banh vào khung

thành – tức

cái âm hộ - anh ta lao cả người vô theo, cùng với trái banh. Ngược hẳn

với cầu

thủ người Nga, buồn bã, u sầu, và hung bạo, hứa hẹn những pha bộc phát

không

thể nào tiên đoán được và cũng thật là đầy chất tranh luận! Mối liên hệ

giữa

anh ta và trái banh làm chúng ta liên tưởng tới những anh chàng yêu

đương dòng

Slav, với những cô bạn gái của họ: đầy thơ ca và nước mắt, và tận cùng

bằng

những pha bắn súng.

Và để kết luận ông

trở lại

với Camus: Khi tôi chào từ biệt ông bạn Andrés, cuối cùng tôi hiểu ra

tại sao

Camus lại nói như vậy, về bóng đá, và tôi quá nôn nao vẽ ra ở trong đầu

mình

những cuộc truy hoan khác thường đang chờ đợi chúng ta, ở Cúp Thế

Giới...

Trước cuộc truy hoan

Bài

viết này, đã từng đăng trên

talawas. Sến cô nương có thể cũng thích nó, và, nhân mùa World Cup đang

nóng bỏng

tại Việt Nam, bèn mail về cho tay chủ báo Tia Sáng, Hà Nội.

Lần Gấu về Việt Nam,

gặp ông này.

Cũng lịch sự biết điều lắm, thưa anh xưng em đàng hoàng. Dân Hải Phòng.

Nhân

chuyến cả đám Gấu và "Bạn Văn VC" đi giang hồ vặt xuống Đất Cảng thăm

BNT, ông đề nghị đi cùng, về thăm gia đình.

Không nhớ vào một lúc nào đó, ông ghé tai cho biết, có nhận được bài

viết, nhưng không đăng.

Thấy Gấu có vẻ ngạc nhiên, vì bài viết có đụng vô vùng

nhậy cảm nào đâu, ông giải thích, không phải vậy, mà là bài anh đểu

giả, xỏ lá

quá!

Sa đích văn nghệ!

Quả là danh bất hư truyền!

“Who

taught you this, doctor?”

The answer came promptly:

“Sufferings”

Ai dậy ông điều này, Bác sĩ?

Đau khổ…

“Do you really imagine you

know everything about life?”

The answer came through the

darkness, in the same cool, confident tone:

“Yes”

Ông thực sự tưởng tượng ông biết mọi chuyện về cuộc đời?

Câu

trả lời vượt qua bóng tối, cũng bằng một giọng tươi mát, tin cậy:

Đúng như thế

The Plague, Dịch hạch, bản

tiếng Anh, người dịch:

Gilbert Stuart (New

York:

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. 1948, pp 118, 119)

*

Le Magazine Littéraire:

Albert Camus là một khuôn mặt

trí thức nổi cộm trong đời sống tinh thần của nước Tẩy… Ngoài ra còn là

một nhân

vật, một huyền tượng…

Olivier Todd: Tôi mất năm năm

với thằng chả, để viết cuốn tiểu sử về hắn ta. Trong đời thường, cũng

cay

đắng ngọt bùi lắm [sucrées-salées: đường ngọt, muối mặn]. Một bữa, vào

những năm

1950, tôi đang ngồi Cà phê Marie, chỗ quảng trường Saint-Sulpice, với

bà vợ tuyệt

trẻ của tôi [avec ma très jeune femme]. Camus tới, ngồi ở quầy, và nhìn

bả như

muốn lột trần truồng bả ra, [qui n’arrête pas de la déshabiller des

yeux.] Tôi tức

điên lên…

Alain Finkielkraut: Tức điên,

hay sướng điên lên? [Furieux ou flatté?]

ALAIN

FINKIELKRAUT*

« Camus plutôt que Sartre»

• Sartre est à la fois un

philosophe de la liberté et un philosophe de la libération. L'homme est

condamné à être libre, montre-t-il dans “l'Etre et le Néant”. Libre,

c'est-à-dire

irréductible à ses appartenances, son identité, sa psychologie même.

Car

l'homme selon Sartre n'est pas substance mais conscience :

non-coïncidence à

soi, arrachement ou échappement originel à toute définition. Le garçon

de café

joue à être garçon de café. J'admire toujours la maestria avec laquelle

Sartre

déébusque, sous le nom de « “mauvaise fois”, ”l'oubli du non-être” et

les ruses

des individus pour croire ou faire croire qu'ils sont ce qu'ils sont.

Je ne

suis plus sûr cependant que cette grande pantomime emmbrasse la

totalité du

phénomène humain.

Mais Sartre dit aussi que

personne n'est encore libre, que la liberté, l'humanité même sont à

venir. Et

cet avenir, il se le figure sous les deux traits de la fraternité et de

la

souveraineté. Aujourd'hui, je ne suis pas moins allergique à ce double

idéal

qu'aux bévues politiques commises en son nom. Pourquoi les hommes

devraient-ils

penser et vivre à l'unisson? La pluralité n'est pas un mal destiné à se

résorber dans une commuunauté fusionnelle, mais une donnée de la

condition

humaine. Et comme le montre

Hannah Arendt, l'humanité s'atteste dans l'amitié

qui vit de la distance entre les êtres, non dans la fraterrnité qui

l'abolit.

Quant à l'idée de

souveraineté ou de règne de l'homme, elle conduit Sartre à intégrer

toute réalité

dans l'histoire et à considérer toute limite comme un obstacle

temporaire ou

une mystification bourgeoise. Le

contraire de ce que fait Camus quand il écrit

que « si la révolte pouvait fonder une philosophie, ce serait une

philosophie

des limites, de l'ignorance calculée et du risque ». Les

sartriens m'ont

longtemps convaincu que Camus était un philosophe pour classe

terminale; je

pense maintenant que rien n'est plus urgent ni plus audacieux que

l'alliance de

la révolte et de la mesure préconisée par “l'Homme révolté”.

(*) Professeur à l'Ecole

polytechnique. Dernier ouvrage paru : «l'Ingratitude» (Gallimard, 1999).

Trích

từ Người Quan Sát, số đặc biệt về Sartre, [13-19 Janvier, 2000], 20 năm

sau khi ông ra khỏi Lò Luyện Ngục, và trở lại!

Bây giờ, nhìn lại, Kẻ Xa Lạ, tuy bảnh như thế, nhưng nếu phải so găng

với Buồn Nôn, Gấu nghĩ, cũng... căng lắm đấy!

*

Hannah Arendt, trong bài viết

Chủ nghĩa hiện sinh Pháp, lần đầu xuất hiện trên The Nation, 162, Feb

23, 1946,

sau in trong Essays in Understanding 1930-1954, trích dịch sau đây:

Một buổi diễn thuyết gây hỗn loạn với hàng trăm người tham dự trong khi

hàng ngàn

người tẩy chay. Sách triết học bán chạy, giống như truyện trinh thám.

Kịch,

thay vì hành động, thì là đối thoại, suy tư siêu hình, vậy mà công diễn

hết tuần

này qua tuần khác. Những nghiên cứu về hoàn cảnh con người trong thế

giới, những

liên hệ cơ bản của con người, Hữu thể và Hư vô, không chỉ dấy lên một

trào lưu

văn học mới, mà còn được coi như những dẫn dắt khả hữu về một đường

hướng chính

trị mới mẻ. Triết gia trở thành nhà báo, ký giả, kịch tác gia, tiểu

thuyết gia.

Họ không còn là những thành viên của những đại học, nhưng mà là những

kẻ xuống đường,

những gã lang thang, những ‘bohemians’, ở khách sạn, sống trong tiệm cà

phê - sống

một cuộc đời công cộng, public life, đến độ chối từ luôn cuộc đời riêng

tư.

Đó là chuyện đang xẩy ra tại Paris,

qua mọi báo cáo,

tin tức. Nếu cuộc Kháng Chiến không hoàn tất nổi một cuộc cách mạng Âu

châu, có

vẻ như, nó lại gây ra, ít ra là tại Pháp, một cuộc nổi loạn thực sự, a

genuine rebellion,

của đám trí thức, mà ở giữa những cuộc chiến, thì ủ rũ như gà chết

[nguyên văn:

mà cái sự ngoan ngoãn trong liên hệ với xã hội hiện đại thì là một

trong những

khiá cạnh buồn bã của cảnh sắc buồn thảm của Âu châu trong giữa những

cuộc chiến).

Và dân chúng Pháp, vào lúc này, thì có thể như quan tâm tới đám triết

gia xuống

đường của họ hơn là đám chính trị gia. Điều này có thể cho thấy, họ

muốn kiếm một

lối thoát ra khỏi hành động chính trị, và lao vào một thứ hành động chủ

nghĩa, activism; nhưng điều này còn

cho thấy,

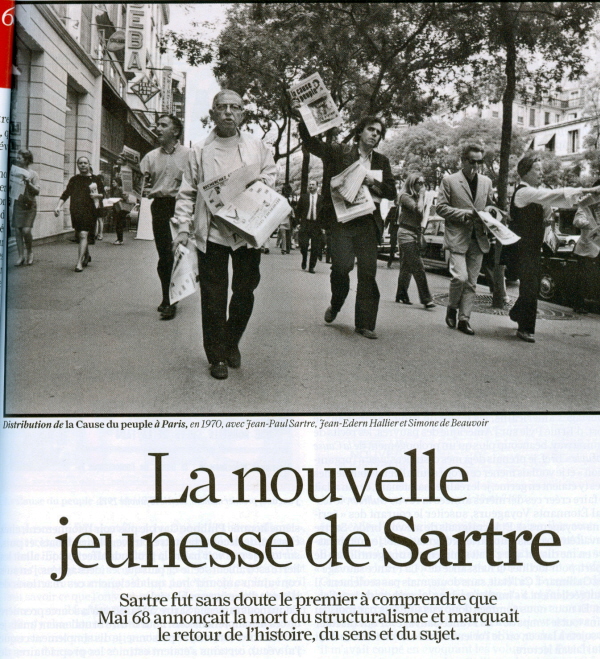

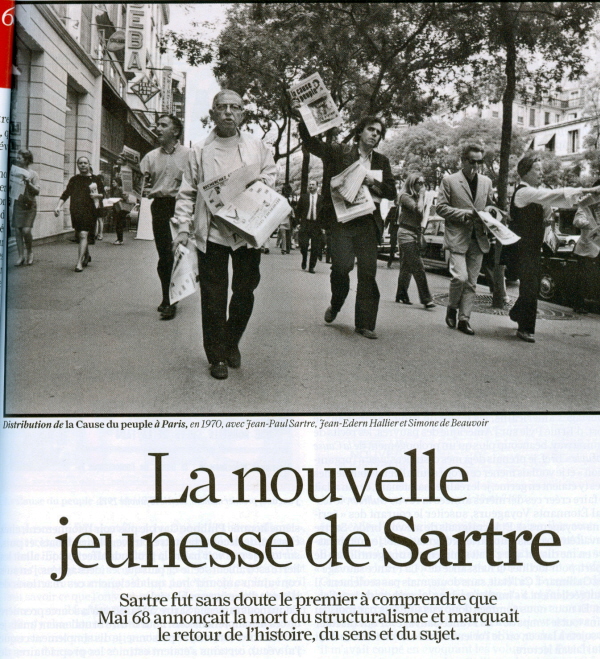

Sartre

là người đầu tiên hiểu

rằng cú Mai 68 là hồi chuông báo tử dành cho cơ cấu luận....

Tribute

to Albert Camus

by Jean-Paul Sartre

Six months ago, even

yesterday, people wondered: "What is he going to do?" Temporarily,

torn by contradictions that must be respected, he had chosen silence.

But he

was one of those rare men we can well afford to wait for, because they

are slow

to choose and remain faithful to their choice. Some day he would speak

out. We

could not even have dared hazard a guess as to what he might say. But

we

thought that he had changed with the world as we all do; that was

enough for us

to be aware of his presence.

He and I had quarreled. A

quarrel doesn't matter-even if those who quarrel never see each other

again-just another way of living together without losing sight of one

another

in the narrow little world that is allotted us. It didn't keep me from

thinking

of him, from feeling that his eyes were on the book or newspaper I was

reading

and wondering: "What does he think of it? What does he think of it at

this

moment?"

His silence, which according

to events and my mood I considered sometimes too cautious and sometimes

painful, was a quality of every day like heat or light, but it was

human. We

lived with or against his thought as it was revealed to us in his

books-especially The Fall, perhaps the finest and least understood-but

always

in relation to it. It was an exceptional adventure of our culture, a

movement

of which we tried to guess the phases and the final outcome.

He represented in our time

the latest example of that long line of moralistes

whose works constitute perhaps the most original element in French

letters. His

obstinate humanism, narrow and pure, austere and sensual, waged an

uncertain

war against the massive and formless events of the time. But on the

other hand

through his dogged rejections he reaffirmed, at the heart of our epoch,

against

the Machiavellians and against the Idol of realism, the existence of

the moral

issue.

In a way, he was that

resolute affirmation. Anyone who read or reflected encountered the

human values

he held in his fist; he questioned the political act. One had to avoid

him or

fight him-he was indispensable to that tension which makes intellectual

life

what it is. His very silence, these last few years, had something

positive

about it: This Descartes of the Absurd refused to leave the safe ground

of

morality and venture on the uncertain paths of practicality. We sensed

this and

we also sensed the conflicts he kept hidden, for ethics, taken alone,

both

requires and condemns revolt.

We were waiting; we had to

wait; we had to know. Whatever he did or decided subsequently, Camus

would

never have ceased to be one of the chief forces of our cultural

activity or to

represent in his way the history of France and of this century.

But we

should probably have known and understood his itinerary. He said so

himself:

"My work lies ahead." Now it is over. The particular scandal of his

death is the aboliition of the human order by the inhuman.

The human order is still but

a disorder: it is unjust and precarious; it involves killing, and dying

of

hunger; but at least it is founded, maintained, or resisted by men. In

that

order Camus had to live. That man on the move questioned us, was

himself a

question seeking its reply; he lived in the middle of a long life; for

us, for

him, for the men who maintain order and for those who reject it, it was

important for him to break his silence, for him to decide, for him to

conclude.

Some die in old age while others, forever on reprieve, may die at any

minute

without the meaning of their life, of life itself, being changed. But

for us,

uncertain without a compass, our best men had to reach the end of the

tunnel.

Rarely have the nature of a man's work and the conditions of the

historical

moment so clearly demanded that a writer go on living.

I call the

accident that

killed Camus a scandal because it suddenly projects into the center of

our

human world the absurdity of our most fundamental needs. At the age of

twenty,

Camus, suddenly afflicted with a malady that upset his whole life,

discovered

the Absurd-the senseless negation of man. He became accustomed

to it, he

thought out his unbearable condition, he came through. And yet one is

tempted

to think that only his first works tell the truth about his life, since

that

invalid once cured is annihilated by an unexpected death from the

outside.

The Absurd might be that

question that no one will ask him now, that he will ask no one, that

silence

that is not even a silence now that is absolutely nothing now.

I don't think so. The moment

it appears, the inhuman becomes a part of the human. Every life that is

cut

off-even the life of so young a man -is at one and the same time a

phonograph

record that is broken and a complete life. For all those who loved him,

there

is an unbearable absurdity in that death. But we shall have to learn to

see

that mutilated work as a total work. Insofar as Camus's humanism

contains a

human attitude toward the death that was to take him by surprise,

insofar as

his proud and pure quest for happiness implied and called for the in·

human

necessity of dying, we shall recognize in that work and in the life

that is

inseparable from it the pure and victorious attempt of one man to

snatch every

instant of his existence from his future death.

"Tribute

to Albert

Camus:' From The Reporter Magazine, February 4, 1960, p. 34.

Copyright 1960 by The Reporter

Magazine Company. Translated by Justin O'Brien. Reprinted by permission

of the

author and The Reporter Magazine.

Camus: A Collection of

Critical Essays

Edited by Germaine Brée

20th Century Views

Albert

Camus: In Memoriam

by Nicola Chiaromonte

[Note:

Đây là bài tuyệt nhất

trong tập Camus: Những tiểu luận có tính phê bình [Camus: A Collection

of

Critical Essays, do Germaine Brée biên tập, nhà xb 20th

Century

Views, 1962]. Tin Văn sẽ có bản chuyển ngữ, sau.]

A man is dead: you think of

his living face, of his gestures, his actions, and of moments you

shared,

trying to recapture an image that is dissolved forever. A writer is

dead: you

reflect upon his work, upon each book, upon the thread that ran through

them

all, upon their vital movement toward a deeper meaning; and you seek to

form a

judgment which takes account of the secret source from which they

sprang, and

which is now stilled. But the picture of the man is not made up of the

sum of

your memories; nor the figure of the writer of the sum of his works.

And one

cannot discover the man through the writer, or the writer through the

man.

Everything is fragmentary, everything is incomplete, everything is prey

to

mortality even when destiny seems to have granted both man and writer

the gift

of living to the limit of his forces, and of giving everything humanly

possible, as in the case of Tolstoy. The story of a man is always

incomplete;

it is sufficient to think of what could have been different-almost

everything-to

know that his story can never contain the meaning of a human life, but

only

what that existence was permitted to be and to give. The truth was the

living

presence, and nothing can replace it. Immortality is an illusion for

thought

and art, as for man. They are nothing but relics mutely surviving

time's

erosion and history's disasters, like monuments of stone. But it is in

this

very fragility-that equates the humblest existence with one we falsely

call

"great," and is simply one that had the luck to express itself-that

there lies the meaning and value of human life. And that value is

eternal.

Albert

Camus appeared in my life in April, 1941, in Algiers,

where I had come as a refugee from France. I met him soon

after my

arrival, for in Algeria

he was famous: the leader of a group of young journalists, aspiring

writers,

students, friends of the Arabs, enemies of the local bourgeoisie and

Pétain.

They lived together, passed the days on the seashore or hillside, and

the

evening playing records and dancing, hoping for the victory of England and giving vent to their

disgust with

what had happened to France

and to Europe. They also put on

plays, and in

that period were preparing a production of Hamlet in which Camus, in

addition

to directing, played the leading role opposite the Ophelia of his wife,

Francine.

He

had published a volume of prose poems entitled Noces

(Nuptials), they told me. I did not read it, because in those

days I was not in the mood for prose poems, but chiefly because the

company of

him and his friends was enough. In their midst I found the France

I loved

and the pure clear warmth of French friendship. I attended the

rehearsals of

Hamlet) went to the beach with them, took walks with them, talking

about what

was happening in the world. Hitler had just occupied Greece,

and the swastika waved over

the Acropolis. I suffered continual nausea and solitude in the face of

these

events. But solitary and shut off as I was, I was the guest of those

young

people. To know the value of hospitality one must have been alone and

homeless.

I

try to recall details, as if through them I could relive those days and

learn

something more about the young writer with whom I actually spoke

little, since

he felt no more like talking than I. I remember being totally obsessed

by a

single thought: we had arrived at humanity's zero hour and history was

senseless; the only thing that made sense was that part of man which

remained

outside of history, alien and impervious to the whirlwind of events.

If,

indeed, such a part existed. This thought I considered my exclusive

privilege.

I felt that no one else could be so possessed by it; yet I yearned for

someone

to share it with. But there was no one. It was not an idea compatible

with

normal life, let alone with literature-or so it seemed to me.

However,

I did have something in common with this twenty-year old writer-love of

the

sea, joy of the sea, ecstatic admiration of the sea. I discovered this

one day

when I was his guest at Oran

and we went by bicycle beyond Mers-el-Kebir to a deserted beach. We

spoke

little even then, but we praised the sea, which does not have to be

understood,

which is inexhaustible and which never palls. All other beauty does, we

agreed.

This agreement sealed our friendship. Camus told me then that he was

writing a

tragedy about Caligula, and I tried to understand what could attract a

modern

writer to such a subject. Unfettered tyranny? But contemporary tyranny

did not

seem to me to have much in common with Caligula's.

From Oran I

continued my journey

to Casablanca

from where I had been told I could embark for New York. I said good-bye to Camus

and his

wife, knowing that we had exchanged the gift of friendship. At the core

of this

friendship was something very precious, something unspoken and

impersonal that

made itself felt in the way they received me and in our way of being

together.

We had recognized in each other the mark of fate - which was, I

believe, the

ancient meaning of the encounter between stranger and host. I was being

chased

from Europe; they remained, exposed

to the

violence that had driven me out. I carried away with me the impression

of a man

who could be almost tenderly warm one moment and coolly reserved the

next, and

yet was constantly longing for friendship.

I

saw him again in New York

in 1946 on the pier where I had gone to meet his ship. In my eyes he

seemed to

me like a man coming straight from the battlefield bearing its marks,

pride and

sorrow. By that time I had read The

Stranger, The Myth of Sisyphus,

and Caligula. In those black years

the young man from Algeria

had fought and conquered. He had become, together with Jean-Paul

Sartre, the

symbol of a defeated France,

which because of them had imposed itself victoriously in its chosen

domain-intelligence. He had won his position on the stage of the world;

he was

famous; his books were brilliant. But to me he had conquered in a more

important sense. He had faced the question which I considered crucial

and which

had so absorbed me during the days that I first met him. He had

mastered it and

carried it to extreme and lucid conclusions. He had succeeded in

saying, in his

fevered way and in an argument as taut as a bow, why, despite the fury

and

horror of history, man is an absolute; and he had indicated precisely

where,

according to him, this absolute lay: in the conscience, even if mute

and

stilled; in remaining true to one's self even when condemned by the

gods to

repeat over and over the same vain task. In this lay the value of The

Stranger

and The Myth of Sisyphus for me.

With

an almost monstrous richness of ideas and vigor of reasoning Sartre had

said

something similar. But when he arrived at the question of the

connection

between man and history today; between man and the choices which impose

themselves today, Sartre seemed to have lost the thread of his

reasoning, to

have turned backward to realism, to categorical obligations imposed on

man from

the outside, and worse, to notions of the politically opportune. Camus

held

firm, at the risk of exposing himself, defenseless, to the criticism of

the

dialecticians, and of seeming to pass brusquely from logic to emotive

affirmation. It is certain that what induced him to remain firm was not

an

ideological system, but the sentiment, so vehemently expressed in The

Stranger

and in some pages of The Myth of Sisyphus,

of the inviolable secret which is enclosed in every man's heart simply

because

he is "condemned to die." That is man's transcendence. That is man's

transcendence in respect to history; that is the truth which no social

imperative can erase. Desperate transcendence and truth, because they

are

challenged in the very heart of man, who knows that he is mortal and

eternally

guilty, with no recourse against destiny. Absurd such transcendence and

truth-but absurd as they were, they were reborn every time that

Sisyphus

descended "with heavy, but equal, steps, toward the torment whose end

he

would never approach .... " This secret, like the "eternal

jewel" of Macbeth can never be compromised or violated without

sacrilege.

Albert

Camus had known how to give form to this feeling and to remain true to

it.

Because of this, his presence added to everybody's world, making it

more real

and less insensate. And because of this, not of his fame, the young

writer from Algeria

has "grown" in my eyes, worthy not only of friendship but admiration.

It was no longer a matter of literature, but of directly confronting

the world.

Literary space, that trompe l'oeil

that had been invented in the nineteenth century to defend the

individual

artist's right to be indifferent, was broken. Camus (and, in his very

different

way, Sartre) by the simple act of raising the question of the value of

existence, asserted the will to participate actively, in the first

person, in

the world; that is, to challenge directly the actual situation of

contemporary

man in the name of the exigence of a conscience whose rigor was not

attenuated

by pragmatic considerations. With this, one might say, he returned to

the

raison d'être of writing. Putting the world in question means putting

one's

self in question and abandoning the artist's traditional right to

remain

separate from his work-a pure creator. In the language of Camus, this

signifies

that if the world is absurd, the artist must live immersed in the

absurd, must

carry the burden of it, and must seek to prove it for others.

This

was the real and the only valid meaning of engagement. Such a choice

carried

within itself the threat of the cancerous negation that Camus called

nihilism.

One had to go through the experience of nihilism and fight it. The

simplest act

of life is an act of affirmation; it is the acceptance of one's own and

others'

lives as the starting point of all thinking. But living by nihilism is

living

on bad faith, as a bourgeois lives on his income.

In

1946 Camus was invited to speak to the students of Columbia University

in New York.

I

have kept notes of his talk, and

am sure I can reconstruct it without betraying his meaning. The gist of

the

speech was as follows:

We were born at

the beginning

of the First World War. As adolescents we had the crisis of 1929; at

twenty,

Hitler. Then came the Ethiopian War, the Civil War in Spain, and Munich.

These were the foundations of our education. Next came the Second World

War,

the defeat, and Hitler in our homes and cities. Born and bred in such a

world,

what did we believe in? Nothing. Nothing except the obstinate negation

in which

we were forced to close ourselves from the very beginning. The world in

which

we were called to exist was an absurd world, and there was no other in

which we

could take refuge. The world of culture was beautiful, but it was not

real. And

when we found ourselves face to face with Hitler's terror, in what

values could

we take comfort, what values could we oppose to negation? In none. If

the problem

had been the bankruptcy of a political ideology, or a system of

government, it

would have been simple enough. But what had happened came from the very

root of

man and society. There was no doubt about this, and it was confirmed

day after

day not so much by the behavior of the criminals but by that of the

average

man. The facts showed that men deserved what was happening to them.

Their way

of life had so little value; and the violence of the Hitlerian negation

was in

itself logical. But it was unbearable and we fought it.

Now

that Hitler has gone, we know a certain number of things. The first is

that the

poison which impregnated Hitlerism has not been eliminated; it is

present in

each of us. Whoever today speaks of human existence in terms of power,

efficiency, and "historical tasks" spreads it. He is an actual or

potential assassin. For if the problem of man is reduced to any kind of

"historical task," he is nothing but the raw material of history, and

one can do anything one pleases with him. Another thing we have learned

is that

we cannot accept any optimistic conception of existence, any happy

ending

whatsoever. But if we believe that optimism is silly, we also know that

pessimism

about the action of man among his fellows is cowardly.

We

oppose terror because it forces us to choose between murdering and

being

murdered; and it makes communication impossible. This is why we reject

any

ideology that claims control over all of human life.

It

seems to me today that in this speech, which was a sort of

autobiography, there

were all the themes of Camus's later work, from The Plague

to The Just

Assassins to The Rebel. But in it

there remained, discreetly in shadow, the other Camus, the one that I

can call

neither truer nor artistically superior, for he is simply "the

other," jealously hidden in his secret being-the anguished, dark,

misanthropic Camus whose yearning for human communication was perhaps

even

greater than that of the author of The

Plague; the man who, in questioning the world, questioned himself,

and by

this testified to his own vocation. This is the Camus of the last pages

of The Stranger and especially the Camus of The Fall in which we hear his deepest

being, the self-tormenting tormentor speak, resisting all forms of

complacency

and moral self-satisfaction. He wrote, "I was persecuted by a

ridiculous apprehension:

one cannot die without having confessed all one's own lies ...

otherwise, be

there one hidden untruth in a life, death would render it definitive

... this

absolute assassination of the truth gave me vertigo. . . ."

With these

words, it seems to me, the dialogue of Albert Camus with his

contemporaries,

truncated as it is by death, is nonetheless complete.

"Albert

Camus: In

Memoriam." From Dissent, VII,

No. 3 (Summer, 1960), 266-270.

Translated by Miriam

Chiaromonte. Copyright 1960 by Dissent.

Reprinted by permission of the author and Dissent.

Albert

Camus

CAMUS

said that the only true

function of man, born into an absurd world, is to live, be aware of

one's life,

one's revolt, one's freedom. He said that if the only solution to the

human

dilemma is death, then we are on the wrong road. The right track is the

one

that leads to life, to the sunlight. One cannot unceasingly suffer from

the

cold.

So he did revolt. He did

refuse to suffer from the unceasing cold. He did refuse to follow a

track which

led only to death. The track he followed was the only possible one

which could

not lead only to death. The track he followed led into the sunlight in

being

that one devoted to making with our frail powers and our absurd

material,

something which had not existed in life until we made it.

He said, 'I do not like to

believe that death opens upon another life. To me, it is a door that

shuts.'

That is, he tried to believe that. But he failed. Despite himself, as

all

artists are, he spent that life searching himself and demanding of

himself

answers which only God could know; when he became the Nobel laureate of

his

year, I wired him 'On salut l'âme qui constamment se cherche et se

demande';

why did he not quit then, if he did not want to believe in God?

At the very instant he struck

the tree, he was still searching and demanding of himself; I do not

believe

that in that bright instant he found them. I do not believe they are to

be

found. I believe they are only to be searched for, constantly, always

by some

fragile member of the human absurdity. Of which there are never many,

but

always somewhere at least one, and one will always be enough.

People will say He was too

young; he did not have time to finish. But it is not How

long, it is not How much;

it is, simply What. When the door shut for him, he had already written

on this

side of it that which every artist who also carries through life with

him that

one same foreknowledge and hatred of death, is hoping to do: I was

here. He was

doing that, and perhaps in that bright second he even knew he had

succeeded.

What more could he want?

William Faulkner

[Transatlantic Review, Spring 1961; the text printed

here has been

taken from Faulkner's typescript. This previously appeared in Nouvelle Revue Française, March 1960, in

French.]

Bài học

về Camus, trong cuốn

sách của cô học trò

trong trại tị nạn Sikew, Thái

Lan

"Hình

như cái số của em

là cứ bị mấy ông thầy thương.

Anh H. cũng là thầy dậy em học đờn. Em đã chọn

anh H., chính em chọn".

Bụi

Albert

Camus, 50 năm sau khi

mất

Albert Camus, la fin du purgatoire

Ra khỏi Lò Luyện Ngục

Le 4 janvier 1960, Albert

Camus disparaissait brutalement dans un accident de voiture. Deux ans

après

avoir reçu le Prix Nobel de littérature. Huit ans après s'être

irrémédiablement

brouillé avec Sartre. Cette mort précoce - il n'avait que quarante-six

ans -

n'y changera rien : une bonne partie de l'intelligentsia parisienne ne

lui

pardonnera jamais d'avoir, dans L'Homme révolté, osé comparer le

stalinisme au

nazisme. Dès lors, Camus, adulé par le grand public, admiré et étudié à

l'étranger, va être boudé par le monde universitaire français. La

sortie, en

1994, du Premier Homme, son dernier roman - inachevé - dans lequel il

explorait

des pistes littéraires inédites, redore son blason d'écrivain.

Aujourd'hui le

penseur est également en passe d'être réhabilité. Dans son numéro 8,

Books se

faisait l'écho des travaux de l'universitaire américain David Sherman.

Pour ce

dernier, l'effondrement des certitudes idéologiques et l'émergence de

valeurs «

éthico-politiques cosmopolites telles que le dialogue entre les

cultures et les

droits de l'homme » ont fait de Camus « un philosophe de notre temps ».

A noter enfin qu'à l'occasion

de ce cinquantenaire, la bibliothèque du Centre Pompidou, à Paris, organise

une journée d'hommage, le

samedi 30 janvier. Une série de personnalités - le philosophe Raphaël

Enthoven,

les écrivains Yasmina Khadra, Laurence Tardieu, Charles Juliet, Virgil

Tanase,

le metteur en scène Stanislas Nordey, le comédien Charles Berling et

David

Camus, petit-fils de l'écrivain, y liront et commenteront un texte de

leur

choix.

Le retour de

Camus

Alors que

s’approche le

cinquantième

anniversaire de la mort d’Albert Camus, en janvier 1960, deux livres

américains

rendent hommage à l’écrivain et moraliste français. Le premier, par David

Caroll, professeur à l’université de Californie, est consacré à «

Camus

l’Algérien ». S’appuyant notamment sur son autobiographie inachevée, Le

Premier Homme, publiée en 1994, il rend compte du rôle du problème

algérien

dans l’élaboration de la philosophie morale de l’ancien Algérois.

Camus, on le

sait, refusa de prendre parti dans la guerre d’Algérie. Il avait

défendu les

droits des « musulmans » à la veille de la Seconde Guerre mondiale,

mais quand

le conflit éclata, en 1954, il fit valoir que l’on n’était pas obligé

de

choisir entre la justice et le massacre des innocents.

Le second ouvrage, par David Sherman, qui enseigne la

philosophie à

l’université du Montana, revient en profondeur sur les accusations

d’inconsistance philosophique dont a été victime l’ancien résistant de

la part

du camp sartrien, dans les années 1950, avant et après le début de la

guerre

d’Algérie. Dans un compte rendu de ce livre publié dans les Notre

Dame

Philosophical Reviews, publication en ligne de l’université

catholique de

Notre Dame (Indiana), le philosophe sénégalais Souleymane Bachir

Diagne

approuve le travail de réhabilitation mené par Sherman.

Normalien, Bachir Diagne, actuellement professeur à l’université

Columbia de

New York, a été l’élève d’Althusser et de Derrida, et connaît bien les

arcanes

de l’intelligentsia française. Tout en s’emmêlant un peu dans les

dates, il

rappelle la méchante querelle qui éclata en 1952 du fait de Francis

Jeanson, un

fidèle de Sartre. Jeanson publia dans la revue de ce dernier, Les

Temps

modernes, un article critiquant L’Homme révolté, paru

l’année précédente.

L’article était intitulé « Albert Camus ou l’âme révoltée », titre

ironique

évoquant la « belle âme » selon Hegel, figure de l’homme, écrit Diagne,

«

incapable d’agir, étant prisonnier de sa posture éthique, pris entre

deux

options qu’il juge également répréhensibles ». Ignorant Jeanson, qu’il

ne

connaissait pas, Camus adressa sa réponse directement à Sartre («

Monsieur le

directeur »), affirmant n’avoir pas de leçon à recevoir de ceux qui «

n’ont

jamais placé que leur fauteuil dans le sens de l’histoire ». Allusion

cinglante

à l’absence d’engagement de Sartre dans la Résistance, alors que Camus,

lui,

avait risqué sa vie, en animant le mouvement Combat. Sartre répondit

avec

brutalité, l’accusant de surcroît d’incompétence philosophique. La

rupture

entre les deux hommes était consommée.

En jeu, le point de vue développé par Camus dans L’Homme révolté,

selon

lequel ni le capitalisme ni le communisme ne méritaient d’être

soutenus. Avant

cela, Camus s’était attiré une critique du même ordre de la part de

Roland

Barthes, après la parution de La Peste, fin 1947. Barthes lui

reprochait

de refuser un véritable « engagement » et de préférer la morale à la

politique.

Sherman considère que nous assistons aujourd’hui à une « renaissance »

de

Camus, et Diagne souscrit à ce point de vue. « L’effondrement des

certitudes

idéologiques fait que Camus n’est plus persona non grata et

mérite

d’être redécouvert comme “un philosophe de notre temps”, selon les mots

qui

clôturent le livre de Sherman. » Depuis la chute du mur de Berlin,

l’heure est

en effet, écrit Sherman, à l’engagement au profit de valeurs «

éthico-politiques cosmopolites telles que le dialogue entre les

cultures et les

droits de l’homme », état d’esprit qui rencontre exactement l’attitude

de

Camus. Sherman souligne aussi un autre aspect très actuel de la

position de

l’écrivain français, son refus de l’esprit de système au profit d’une

observation attentive du monde réel. Autre forme d’opposition à

l’auteur de L’Être

et le Néant et de la Critique de la raison dialectique.

Dimanche

3 janvier 2010

Le succès du Premier Homme

vu

d'Amérique

Le lundi 4 janvier sera placé

sous le signe d’Albert Camus, décédé le 4 janvier 1960. En guise de

préambule,

nous vous proposons de redécouvrir Le Premier Homme, son dernier roman,

laissé

inachevé par sa disparition brutale. Le manuscrit se trouvait dans la

voiture à

bord de laquelle l’écrivain eut son accident mortel. Il ne fut publié

qu’en

1994. Tony Judt en fit la recension dans la New York Review of Books.

Il y

expliquait notamment pourquoi cette sortie tardive avait permis à

l’ouvrage de

rencontrer un grand succès.

Selon Judt, la France

est

alors mûre pour entendre ce que Camus a à lui dire : « Il est certain

que ce

renouveau d’intérêt est tout sauf inattendu. Dans l’atmosphère délétère

de

corruption qui caractérise la fin de l’ère mitterrandienne, une voix

morale

audible manque cruellement. » Camus vient combler cette lacune. Autre

raison de

son succès, d’après Judt : « les Français ont pris conscience qu’ils

négligeaient et laissaient se délabrer leur héritage littéraire ;

Albert Camus

est l’un des derniers représentants d’un âge d’or de la littérature

française,

il fait le lien avec Roger Martin du Gard, Jules Romains, Gide, Mauriac

et

Malraux. »

Enfin, poursuit le critique,

« le traumatisme de la Guerre d’Algérie est dernière nous ». C’est là

une

condition nécessaire pour que Le Premier Homme, où Camus, renouant avec

la

veine autobiographique, se penche sur son enfance algérienne et sur la

figure

de son père, bénéficie d’une réception sereine : « Le monde perdu de

l’Algérie

française est au cœur de ce dernier roman. C’est un sujet auquel les

lecteurs

français sont ouverts désormais, d’une façon qui n'aurait pas été

envisageable

en 1960 ».

*

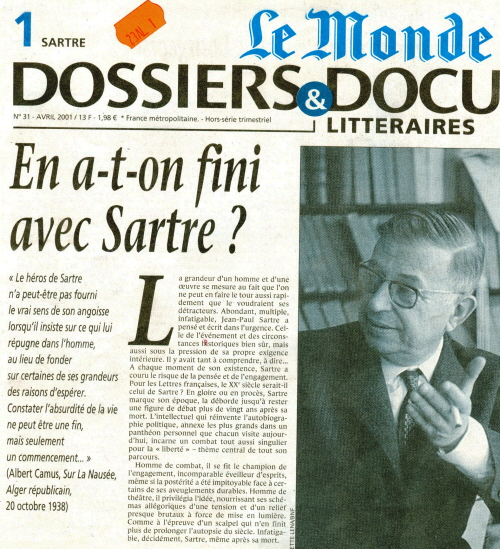

Ui chao, cái bài viết về

Camus, trong phụ trang văn học của tờ Le Monde [Dossiers &

Documents

Littéraires,

Juillet, 2002, “Đứa trẻ & Nhà văn”, L’enfant et l’écrivain], về

cuốn Le

Premier Homme, cuốn sách viết dở dang của Camus, mới tuyệt làm

sao. Bài

viết được

đưa vô chuyên mục “Tuổi thơ trong tự thuật”, với Camus, Sartre, Perec,

Yourcenar. Độc giả Mít có thể kể thêm Nguyên Hồng, với Những ngày thơ

ấu, hay

Nguyễn Đức Quỳnh, với Thằng Kình,

thí dụ.

Tìm lại đứa bé, những kỷ niệm

thời ấu thơ, là tìm lại những cái mầm của tác phẩm sẽ có, và điều quyết

định sự

hiện hữu của kẻ được gọi là người lớn trong cuộc đời. Đó là điều mà

bằng tài năng,

họ đã làm được, trong số “họ” đó, có những nhà văn như Camus, Perec,

Sartre và

Yourcenar.

Cái quá

khứ không làm sao chữa

cho lành lặn được của Camus

Người thứ nhất, Le Premier

Homme, là phác thảo của một cuốn đại tiểu thuyết tự thuật mà nhà

văn

đang loay

hoay, hì hục, thì bị cái chết đánh gục.

Tin Văn sẽ post và

dịch trong kỳ tới!

Cùng trong số báo, còn có một

bài thật tuyệt về bà trùm lưu vong, và tuổi thơ Nga của bà, bị chôm

mất!

Un exil fondateur

Dans toute l’oeuvre de

Nathalie Sarraute résonne sa jeunesse russe qui lui fut volée

Ui chao, giá mà chôm được câu

này, áp dụng vào trường hợp Gấu nhà văn, thì thích quá, hỉ!

*

Cái phụ trang văn học Đứa bé

& Nhà văn, gồm quá nhiều bài viết hách xì xằng. Có thể, đụng vô

‘đứa bé’, là

đụng vô cái mầm văn chương tuyệt vời nhất, chăng?

Ui chao, lại nhớ BHD: Mi đâu

có thương yêu gì ta, mi thương đứa con nít 11 tuổi, là ta từ đời thuở

nào, và cái

xứ Bắc Kít của mi, ở trong đứa con nít đó!

Làm sao mà em "biết" được, những

sự thực khủng khiếp đến như thế?

Bạn đọc chắc còn nhớ đứa con

nít, mà sau này, trở thành nhà văn lẫy lừng Virginia Woolf, khi mới đâu

ba, bốn

tuổi, bị một đứa bà con mò mẫm: Không phải chỉ một đứa con nít trong

tôi, mà cả

một nửa nhân loại, thét lên: NO!

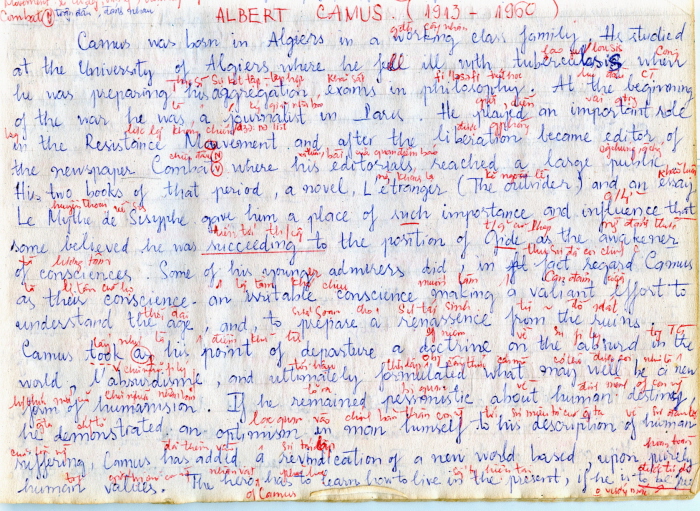

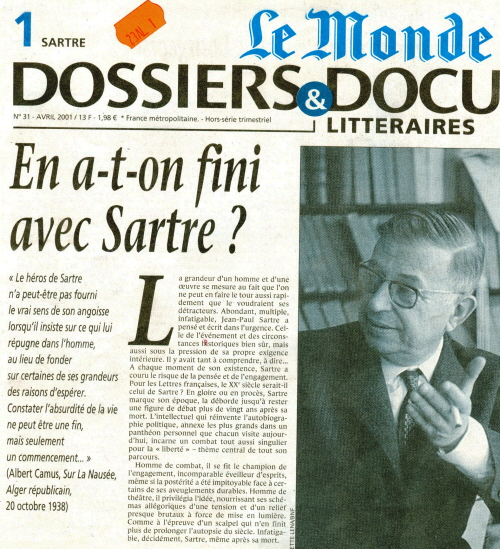

Constater l'absurdité de la vie ne peut être une

fin, mais

seulement un commencement.. »

(Albert Camus, Sur La Nausée, Alger

républicain,

20 octobre 1938)

[Le Monde. Dossiers

& Documents Littéraires. Avril 2001]

Nhìn ra cái sự phi lý của

kiếp người không phải tận cùng mà chỉ là khởi đầu...

L'émotion

ne nous quitte

guère au fil de la lecture. De cette enfance vécue dans un tel état

d'innocence, de ferveur, se dégage une bouleversante impression de

pureté,

presque de grâce. Avec L'Envers et

L'Endroit, Le Premier Homme est

l'un des rares textes quasi autobiographiques d'un écrivain qui

répugnait

pourtant aux confidences. On sait qu'il devait prendre la forme d'un

triptyque:

une première partie consacrée à l'enfance, une deuxième à

l'adolesscence et à

la maturité (l'action politique, l'Algérie, la Résistance), et une

troisième (“la mère”), abordant notamment «

la question arabe, la civilisation créole

et le destin de l'Occident ».

Nous n'aurons donc jamais que

le premier tableau de cet ensemble, depuis la naissance à Mondovi, en

1913,

jusqu'aux distributions des prix, au Grand Lycée d'Alger, vers 1928.

Mais quel

salut vibrant à ces années décisives, « à mi-distance de la misère et

du soleil

», à cette enfance dont Camus écrit ici qu'il n'a «jamais guéri»! Quel

hommaage

à l'Algérie des années 1920, à l'époque bénie où «bicots»

et «francaouis»

supportaient encore de vivre ensemble! Quelle tendressse pour ces

atmosphères

grouillanntes et colorées! Quel hymne au soleil, à la mer, à la lumière!

Certains accents lyriques

rappelleront les ivresses de Noces. D'autres

évoqueront plutôt l'Envers et l'Endroit,

et l'idée qu'« il n'y a pas d'amour de vivre sans désespoir de vivre ».

Ici,

bien sûr, l'envers de la lumière, c'est la pauvreté, la petite maison

de

Belcourt, ce faubourg populaire d'Alger, où Camus grandit entre une

grandmère

autoritaire et une mère illetttrée, isolée dans une demi-surdité. Une

existence

rude et âpre où éclate pourtant la noblesse des vies humbles,

obstinées, ainsi

que la dette de Camus envers cette famille qui, «par son

seul silence, sa réserve, sa fierté », lui donnera pour

toujours «ses plus hautes leçons ».

Mais ce qui apparaît dans Le Premier Homme, avec plus

de force

qu'ailleurs, c'est « le vide affreux» causé par l'absence du père. La

moitié du

roman est consacrée à la « recherche»

de cet homme parti un jour de 1914 dans son costume de zouave

multicolore. Parti se faire tuer à la

bataille de la Marne,

alors que son fils n'avait même pas un an. Malheureusement, «la

mémoire des pauvres est moins nourrrie

que celle

des

riches. Elle a moins de repères dans l'espace puisqu'ils quittent

rarement le

lieu où ils vivent, moins de repères aussi dans le temps d'une vie

uniforme et

grise ». Au bout du compte, pour Camus, il ne restera jamais de ce

père que

l'éclat d'obus qui lui a ouvert la tête, et que l'on conserve

pieusement dans

une boîte à biscuits, dans l'armoire, avec les cartes postales écrites

du front.

Entre les deux femmes qui l'entourent, et malgré l'infinie tendresse

qu'il

nourrit pour sa mère, Camus est le seul homme, le «premier

hommme ».

Il lui faudra s'élever «au prix le plus cher », «trouver

seul sa

morale et sa vérité ». C'est ce parcours intérieur que retrace Le Premier Homme, de l'innocence

première à la prise de conscience de ses origines et à l'acceptation de

soi.

Et, sur ce chemin semé d'embûches, un père de substitution surgira,

providentiel

: c'est Louis Germain, l'instituteur, qui, ayant remarqué ce garçon

bouillant,

exceptionnellement intelligent, bouleversera son destin en le

présentant à la «bourse des lycées et collèges ».

Il faudrait pouvoir dire

quelle reconnaissance affectueuse Camus gardera toute sa vie pour cet

homme, et

l'éloge de l'école laïque que constitue implicitement son texte. Il

faudrait

pouvoir rendre compte du luxe de détails, de la précision inouïe des

souvenirs,

des émotions, des sensations, qui font le prix de ce témoignage: les

siestes

obligées dans le même lit que la grand-mère, lorsqu'il sentait près de

lui «l'odeur de chair âgée », la cave

«puante et mouillée» où les enfants s'échangeaient les berlingots à la

menthe,

le gros fils du boucher surnommé Gigot, la cravache grossière qui lui

cinglait

les fessses lorsqu'il rentrait tard de la plage, les premières

lectures, L'Intrépide, les Pardaillan

(comme Sartre !) où il « s'exaltait à des histoires

d'honneur et de courage ... »

Ce « dernier Camus» constitue

un document exceptionnel sur la formation d'une des plus hautes

consciences du

siècle, sur son hisstoire, son caractère, les ferments de sa pensée.

Tout Camus

est là, en germe, dans l'enfant qui grandit sous nos yeux: la

sensibilité, la

loyauté, la générosité, la droiture, la responsabilité, la fierté, la

soif

d'absolu, l'exigence ... Et aussi une avidité de vivre qui coexiste

touujours

avec un chagrin sourd, inextinguible, comme la basse continue de son

existence.

FLORENCE NOIVILLE (16 avril

1994)

Le Monde. Dossiers &

Documents Littéraires

Albert

Camus, 50 năm sau khi

mất

L'ENFANCE DANS

L'AUTOBIOGRAPHIE

Tuổi thơ trong tự thuật

Le passé

inguérissable de

Camus

Cái quá

khứ không thể lành của Camus

“Le Premier Homme” est

l'ébauche du grand roman autobiographique auquel l'écrivain travaillait

"Người thứ nhất", "Le Premier

Homme", là phác thảo của một cuốn đại tiểu thuyết tự thuật mà

nhà

văn

đang loay

hoay, hì hục, thì bị cái chết đánh gục.

Retrouver

l'enfant, les

souvenirs d'enfance, c'est retrouver les germes de l'œuvre à venir et

ce qui a

déterminé la présence de l'adulte au monde. C'est ce qu'ont fait avec

talent,

entre autres, Rousseau, Perec, Camus, Sartre et Yourcenar.

Tìm lại đứa bé, những

kỷ niệm

thời ấu thơ, là tìm lại những cái mầm của tác phẩm sẽ có, và điều quyết

định sự

hiện hữu của kẻ được gọi là người lớn trong cuộc đời. Đó là điều mà

bằng tài năng,

họ đã làm được, trong số “họ” đó, có những nhà văn như Camus, Perec,

Sartre và

Yourcenar.

Cảm xúc không

rời chúng ta theo

từng trang sách. Một tuổi thơ thật ngây

thơ, thật hăm hở, từ đó toát ra một sự thuần khiết, gần như một ân

sủng. Cùng với Mặt trái và Mặt phải, Người đàn ông thứ nhất

là một trong bản văn

hiếm, dưới dạng gần như tự thuật, của một nhà văn vốn tởm lợm cái trò

tâm sự ỉ ôi.

Người ta biết, nó phải gồm ba phần: phần thứ nhất dành cho tuổi thơ,

thứ nhì

thuở mới lớn và tuổi trưởng thành (hoạt động chính trị, xứ Algérie,

Kháng chiến),

và phần thứ ba (“mẹ”), đề cập đặc biệt tới “vấn đề Ả Rập,

văn hóa da

trắng ở xứ thuộc địa, và số phận của Tây phương”

Prince of the absurd

Ông Hoàng của Sự Phi Lí

WHEN

Albert Camus was killed

in a car crash 50 years ago on January 4th, at the age of 46, he had

already

won the Nobel prize for literature, and his best-known novel,

“L’Etranger”

(“The Stranger” or “The Outsider”), had introduced readers the world

over to

the philosophy of the absurd. Yet, at the time of his death, Camus

found

himself an outcast in Paris,

snubbed by Jean-Paul Sartre and other left-bank intellectuals, and

denounced

for his freethinking refusal to yield to fashionable political views.

As his

daughter has said: “Papa was alone.”

Today, by contrast, the

French are proud to consider Camus a towering figure, while Sartre’s

star has

faded. Even President Nicolas Sarkozy, from the political right, has

proposed

transferring the writer’s remains from Provence

to the Panthéon in Paris.

Several new books mark the anniversary of his death, including an

elegant

illustrated volume by Catherine Camus, one of his twin children and

custodian

of her father’s estate.

The reader in search of

literary criticism, or even the origins of absurdist thought, will not

find it

in the three new biographies. That by José Lenzini, a French former

journalist,

is the most unusual, retracing Camus’s last journey from Provence

to Paris

as a

series of imaginary flashbacks through his life. The other two are more

conventional but both finely drawn, digestible portraits of the

football-playing “little poor child”, as Camus called himself, from Algiers, who

came to

leave such a mark on literature and moral thought.

A double haunting presence

looms throughout all the books: that of Algeria, where Camus was

born, and

of his mother, Catherine. Before he was a year old, the infant Albert

lost his

father, an early settler in French Algeria, in the battle of the Marne. His mute and illiterate mother, and her

extended

family, raised her two sons in a small flat in Algiers with neither a lavatory nor

running

water. Alain Vircondelet writes movingly of the “minuscule life” in the

apartment with nothing: “those white sheets, his mother’s folded hands,

a

handkerchief and a little comb.” Her purity and silent dignity marked

her son,

as he struggled to confront his own shame at such poverty—and his shame

at

being ashamed. “With those we love,” he once said of her, “we have

ceased to

speak, and this is not silence.”

That the young Albert went to

the French lycée, and then to university in Algiers, was thanks to two inspiring

teachers

with whom he kept in touch throughout his life; he dedicated his Nobel

prize to

one of them. Camus began writing, as a reporter and dramatist, in a

land that

was then part of France—and

yet apart. His was the solitude, self-doubt and restlessness of

dislocation and

displacement. The young man who emerges from Virgil Tanase’s biography

in

particular is seductive, funny and loving, but constantly on the move:

between

the raw, sun-drenched Mediterranean and cramped, grey Paris, ever in

search of

respite from crippling bouts of tuberculosis, as well as comfort from

the

various women he charmed and loved with a passion.

History finds Camus on the

right side of so many of the great moral issues of the 20th century. He

joined

the French resistance to combat Nazism, editing an underground

newspaper,

Combat. He campaigned against the death penalty. A one-time Communist,

his

anti-totalitarian work, “L’Homme Révolté” (“The Rebel”), published in

1951, was

remarkably perceptive about the evils of Stalinism. It also led to his

falling-out with Sartre, who at the time was still defending the Soviet Union and refusing to condemn the gulags.

Camus left Algeria

for mainland France,

but Algeria

never left him. As the anti-colonial rebellion took hold in the 1950s,

his refusal

to join the bien pensant call for independence was considered an act of

treason

by the French left. Even as terror struck Algiers,

Camus was vainly urging a federal solution, with a place for French

settlers.

When he famously declared that “I believe in justice, but I will defend

my

mother before justice,” he was denounced as a colonial apologist.

Nearly 40

years later, Mr Lenzini tracked down the Algerian former student who

provoked

that comment at a press conference. He now confesses that, at the time,

he had

read none of Camus’s work, and was later “shocked” and humbled to come

across

the novelist’s extensive reporting on Arab poverty.

The public recognition that

Camus achieved in his lifetime never quite compensated for the wounds

of

rejection and disdain from those he had thought friends. He suffered

cruelly at

the hands of Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir and their snobbish, jealous

literary

clique, whose savage public assassination of Camus after the

publication of

“The Rebel” left deep scars. “You may have been poor once, but you

aren’t

anymore,” Sartre lashed out in print.

“He would remain an outsider

in this world of letters, confined to existential purgatory,” writes Mr

Lenzini: “He was not part of it. He never would be. And they would

never miss

the chance to let him know that.” They accepted him, says Mr Tanase,

“as long

as he yielded to their authority.” What Sartre and his friends could

not

forgive was the stubborn independent-mindedness which, today, makes

Camus

appear so morally lucid, humane and resolutely modern.

|

|