|

Ukraine

Trật

tự thế giới mới Tin Văn tính dịch, nhưng

lại

khoái bài Phát Xít,

Nga, và Ukraine, của Timothy Snyder trên tờ NYRB hơn. Tương

lai của cuộc chống đối này sẽ được quyết định bởi người dân Ukraine.

Tuy nhiên,

nó bắt đầu với niềm hy vọng rằng, xứ Ukraine sẽ có 1 ngày gia nhập Liên

Âu, một

hoài vọng, với nhiều người dân ở đây, có nghĩa là, một điều gì đó như,

sống

bằng, theo luật pháp, hết còn sợ, hết còn tham nhũng, ung thối, một nhà

nước có

chế độ trợ cấp xã hội, và những thị trường tự do không còn bị bàn tay

lông lá của

những băng đảng mafia đằng sau có ông nhà nước độc tài thao túng, và

ông Trùm

đích thực, là Ngài Tổng Thống. Ở đây, có 1

cái gì tương tự với Cuộc Chiến Mít, và cái gọi là lòng dân Bắc Kít, khi

giới trẻ

của Miền Bắc, chừng vài thế hệ liên tiếp, nhỏ máu đầu ngón tay, viết

đơn tình

nguyện xẻ dọc Trường Sơn kíu nước. Đó là phía

"Thiên Sứ" của cuộc chiến Mít. Be careful what you

struggle for – you will

problaly get

it Graham Greene

cũng đã than giùm dân Mít, khi viết về trận DBP: The Sinister Spirit

sneered: "It had to

be!" Võ Tướng

Quân, với trận DBP, chấm dứt Cuộc Chiến Mít I Cuộc chiến

Mít I chấm dứt đưa đến cuộc di cư khổng lồ. Bass: The Spy Who Loved Us Chuyện Ẩn gây chấn động ở nơi tôi, như một điều gì từ Graham Greene bước thẳng ra." David Halberstam nói. Ông là bạn của Ẩn, thời gian ông là phóng viên [Nữu Ước]Thời Báo [Times] tại Việt Nam. "Nó đụng tới những câu hỏi sinh tử: Trung thành là gì? Yêu nước là gì? Sự thực là gì? Anh là ai, khi anh đang nói ra những sự thực đó?" Và ông nói thêm, "Có cái điều lập lờ, nước đôi, ở nơi Ẩn, những con người như chúng ta hầu như không thể tưởng tượng ra nổi. Nhìn ngoái lại, tôi thấy một con người nứt ra làm đôi, Ẩn đó". Cao Bồi The assault began on 13 March 1954, and Dien Bien Phu fell on 7 May, the day before the delegates turned at last from the question of But General Giap could not be confident that the politicians of the West, who showed a certain guilt towards the defenders of Dien Bien Phu while they were discussing at such length the problem of Korea, would have continued to talk long enough to give him time to reduce Dien Bien Phu by artillery alone. So the battle had to be fought with the maximum of human suffering and loss. M. Mendes-France, who had succeeded M; Laniel, needed his excuse for surrendering the north of Vietnam just as General Giap needed his spectacular victory by frontal assault before the forum of the Powers to commit Britain and America to a division of the country. The Sinister Spirit sneered: 'It had to be!'

And again the Spirit of Pity whispered, 'Why?' Cuộc tấn

công bắt đầu này 13 Tháng Ba 1954, và DBP thất thủ ngày 7 Tháng Năm,

trước khi

các phái đoàn, sau cùng rời vấn đề Korea qua số phận Đông Dương. Con ma nham

hiểm Bắc Kít, Con Quỉ Chuồng Lợn của Kafka, bèn cười khinh bỉ: Phải thế

thôi! Graham Greene: Ways of Escape

COMMENT TERMS OF

CRISIS Annexation

has an ugly sound, owing to an unhappy past. The term describes, among

other

tragedies, Saddam Hussein's attempt, in 1990, to swallow Kuwait whole,

as the nineteenth

province of Iraq; Indonesia's invasion, in 1975, of East Timor;

Morocco's

absorption, the same year, of Western Sahara; and Israel's declaration,

after

the 1967 war, of East Jerusalem as part of a united capital. The German

word

for it is Anschluss. Like most

coerced unions, annexations come wreathed in clouds of lofty, dishonest

language-key themes are popular will, historic grievance, divine

providence-but

they almost always happen at the end of a gun. Vladimir Putin's speech at

the Kremlin last week, asking a compliant

Duma to ratify Crimea's self-declared status as a new Russian republic,

was a

memorable example of annexation rhetoric. Putin opened with the baptism

of

Prince Vladimir in ancient Khersones, railed against years of

humiliation by

the West, warned of consequences for unnamed "national traitors"

inside Russia, and moved the audience to tears on behalf of his

people's hearts

and minds, where "Crimea has always been an inseparable part of

Russia." A few of his points had merit: it's true that the United

States,

like other great powers, ignores international laws when they get in

the way,

and it should have been foreseeable that Russia would view the

expansion of

NATO as a challenge to its interests. Other parts of the speech were

blatant

falsehoods- for example, the charge that Russian speaking Ukrainians

were under

threat from hordes of neo- Nazis, and the claim that "Russia's armed

forces never entered Crimea." When Putin thanked his Ukrainian brothers

for refraining from shedding blood, he neglected to mention that they

had been

disarmed by Russian special-forces troops. The annexation of Crimea

is now what Putin calls "an

accomplished fact." It won't be

undone for a long time, if ever. The referendum was illegal under

Ukrainian and

international law and was held in far from free circumstances, but the

result

probably reflected the majority will. More to the point, the U.S. and

Europe won't

risk the effort to reverse the annexation, because they have minimal

interests

in Crimea, while Russia, with great interests, will risk almost

anything to keep

it. But the fate of the rest of Ukraine and of the other former Soviet

republics, along with the future of relations between Russia and the

West,

remains very much unresolved. Any American policy needs to begin with

an

understanding of what the crisis is and what it isn't. Ukraine is not

Czechoslovakia. For some American hawks, the year

is always 1938, and Munich and appeasement are routinely invoked

whenever there's

an act of aggression any- where in the world. John McCain and Hillary

Clinton

both pointed to the superficial analogy between Crimea and the

Su-detenland-annexation

in the name of ethnic reunification. Before the referendum,

pro-Ukrainian

protesters in Kiev held up signs depicting Putin with Hitler's black

bangs and toothbrush

mustache. All this inflates Putin's importance far beyond his deserts.

He may want

Russia to lead a new Eurasian Union, but he doesn't dream of world

conquest;

Russia has plenty of nuclear weapons, but its conventional military

forces are

ill prepared for a long occupation of Ukraine. Nor is the crisis a

revival of

the Cold War-a comparison drawn both on the right, by McCain, in a Times

Op-

Ed, and on the left, by Stephen F. Cohen, in The Nation. That

conflict

divided the world into two camps, in a titanic struggle of ideas, with

countless

hot wars fought by proxies of the superpowers. The messy Ukraine crisis

is what

the world looks like when it's not divided into two spheres of control.

Putin

stands for the opposite of a universal ideology; he has become an

arch-nationalist

of a pre-Cold War type, making mystic appeals to motherland and

religion. He loves

to challenge the supposed bullying of the West, but he does so with

scarcely

any support beyond Russia and the twenty million Russian speakers who

live in

former Soviet republics. He was warmly congratulated after the

annexation by

his friend Bashar al-Assad, of Syria, but a United Nations resolution

condemning Russia's actions won the approval of every Security Council

member

except China, which abstained (perhaps thinking of its own separatists

in Tibet),

and Russia itself. It's essential for the

U.S. and Europe to prevent Putin from going

farther and reversing the hard-won independence of former Soviet

republics.

Moscow is actively trying to destabilize cities in eastern Ukraine,

following

the familiar strategy of whipping up fear and chauvinism among Russian

speakers. The Western countries should use all the non-military tools

at their disposal-money,

diplomacy, political support, trade inducements that build on the

political

accord signed last Friday, poll monitors-to insure that Ukraine doesn't

collapse into chaos before the Presidential elections on May 25th, and

that the

vote is fair. Ukrainian leaders are wisely making space for pro- Russia

politics and promising a degree of federalism under a new government.

Ukrainians shouldn't feel compelled to choose, for the sake of safety

and

identity, between Russia and the West- that's what Putin wants. A successful election in a

stable Ukraine is half the battle against

Putin's aggression. The other half is deterrence. It would be naive to

take

Putin at his word that Russia has no designs on territory outside

Crimea. He

needs an atmosphere of continuous crisis and grievance to maintain

support at

home, to distract his own public from the corruption, stagnation, and

repression that are his real record as a leader. Deterrence can be

designed to

expose Russia's weakness: non-lethal military aid to Kiev, escalation

of

sanctions against Putin's cronies, and the ultimate threat of

financially

targeting Russia's energy sector. But no strategy will work if the U.

S. and

the European Union don't act together, and America can no longer simply

expect

Europe to follow its lead. That was a different era. Is all this Barack Obama's

fault, as Republicans in Congress and

former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice have asserted? It's true

that the

Administration seems caught off guard when- ever a thug somewhere fails

to act

according to international norms. Putin no doubt views the President as

weak,

especially after Obama needed Russia to get him out of a jam of his own

making

over Syria's chemical weapons--and, like any bully, . Putin finds

weakness

provocative. But Crimea was a long time coming. In 2008, when George W.

Bush

was President, Putin, after voicing many

of the resentments that the world heard last week, invaded the Republic

of

Georgia and all but annexed two predominantly Russian-speaking

territories

without even bothering to hold a referendum. An autocrat like Putin

plays his

own game, and always finds his own excuses. -George

Packer THE NEW YORKER MARCH 31, 2014 Note: Bài viết

mới nhất trên “Người Nữu Ước”, về cú "Nối Vòng Tay Nhớn", Anh Cả Bắc

Kít Putin đợp Crimea, “cũng thuộc Nga mà”: “Crimea mãi mãi là một phần

không thể

tách rời Nga.” "Crimea has always been an inseparable part of

Russia." Phát Xít,

Nga, và Ukraine Timothy

Snyder Sinh viên là

những người đầu tiên chống lại chế độ của Tổng Thống Viktor Yanukovych

ở

Maidan, quảng trường trung tâm Kiev, tháng 11 vừa rồi. Họ là những

người dân

Ukraine mất nhiều nhất, những người trẻ tuổi, khinh xuất nghĩ về chính

mình như

những người Âu Châu, và mong ước cho họ một cuộc đời, và một quê hương

Ukraine,

nghĩa là Âu Châu. Rất nhiều trong số họ về mặt chính trị, tả, một số

trong họ,

gốc tả. Sau nhiều năm thương lượng và nhiều tháng hứa hẹn, chính quyền

của họ,

dưới triều Tổng Thống President Yanukovych, vào giờ phút chót, đã thất

bại

trong việc ký kết một hiệp ước thương mại chủ yếu, trọng đại, với Liên

Âu. March 3,

2014 Ukraine

Crisis: Keep Your Eyes on Angela Merkel

Niên Xô [Hà Lội]: Nhà Nước Ma-Phia Mấy dòng trên,

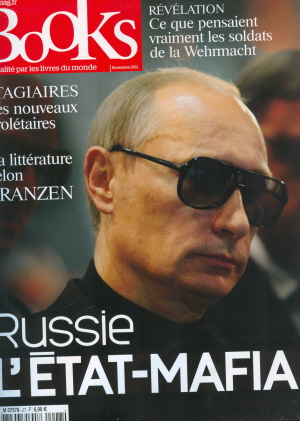

là được gợi hứng từ cái tít bài viết của David Remnick: Chẳng phải. Khó, là trước đó chưa có, và hiện nay chỉ có nó, theo tờ Books. Ngoài cái tên của Remnick, còn 1 cái tên do tờ báo đề nghị: Nền độc tài của lũ ba vạ, la dictature des médiocres. Médiorcre: Xoàng. Tồi. Học lớp 1, chăn trâu, y tá dạo, làm độc tài thì xoàng thật. Nhưng, ở Nga, khác ở xứ Mít, nhà văn đã bắt đầu ngó vào chế độ. TV sẽ giới thiệu bài viết của số báo trên: Ce que disent les écrivains. Điều nhà văn nói. Ukraine Ukraine

Timothy Snyder The students

were the first to protest against the regime of President Viktor

Yanukovych on

the Maidan, the central square in Kiev, last November. These were the

Ukrainians with the most to lose, the young people who unreflectively

thought

of themselves as Europeans and who wished for themselves a life, and a

Ukrainian homeland, that were European. Many of them were politically

on the

left, some of them radically so. After years of negotiation and months

of

promises, their government, under President Yanukovych, had at the last

moment

failed to sign a major trade agreement with the European Union. —February

19, 2014 Tin

Văn scan hai bài trên The Economist liên quan vụ

Ukraine, từ báo giấy.

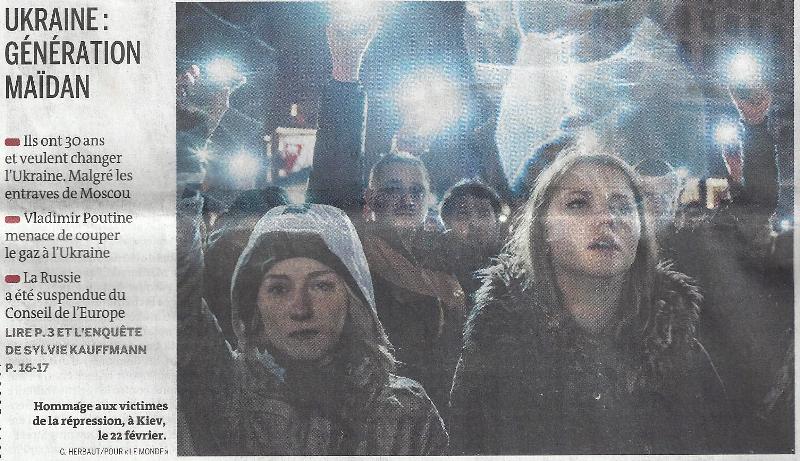

Jerome Sessini/Magnum Photos Wounded

protester, Kiev, Ukraine, February 2014 Người biểu

tình bị thương Kiev, Ukraine, February 2014 Trúng Quả Lừa Every time I

see a large crowd of people on TV or in a newspaper, demonstrating

against some

autocratic government, I have mixed feelings: admiration for their

willingness

and bravery to take a stand, and a foreboding that nothing will come

out of the

effort. This sad conclusion comes from seeing too many worthy causes

and mass movements

fizzle out over the years. But even by that grim reality the defeat of

democracy movements across the Middle East and North Africa, following

protests

that brought out millions of people, is staggering. Not that these were

the

only places where crowds were demanding change. There were mass

demonstrations

in Greece, Bulgaria, Mexico, Brazil, Peru, Spain, Portugal, and many

other

countries, caused by the global economic crisis and governments

instituting

austerity measures, but what has happened in places like Syria and

Egypt and

now Ukraine is more serious, since protesters have questioned the

legitimacy of

the state and made demands for fundamental reform or the overthrow of

the men

and institutions who stand in the way of popular will. Although most

of us know little about the history and culture of these countries, we

have

seen the faces of protesters, old and young, and from all walks of

life; and

although they may look different than our own compatriots, we can

understand

their anger and disgust with the political system they have been living

under

and their determination and vulnerability as they confront armed

representatives of a corrupt state. How exhilarating it was in 2011 to

see

hundreds of thousands of people pouring into the streets and scaring

the hell

out of those in power. It made me recall the heady days of protests

against the

wars in Vietnam and Iraq, the naïve conviction we had as participants

that our

voices would be heard and would prevail against what seemed to us then,

and proved

subsequently to be, acts of moral and strategic idiocy, leading to

slaughter of

countless of human beings and destruction of their countries. Nonetheless, for weeks, and even months, watching the crowds at Tahrir Square and elsewhere we were hopeful. Their demands appeared not only reasonable, but irreversible, even though there were plenty of signs that those in power intended to strike back. I remember, for example, seeing on TV a clip of a demonstration in Bahrain, or in some other Gulf State, where the following scene took place. A distinguished-looking elderly man in a white suit stepped out of the crowd of demonstrators and approached a platoon of armed soldiers with their rifles pointed. He was speaking to them calmly when, without any warning, one of the soldiers lifted his weapon and shot the man in the head. There was plenty more violence everywhere during the months of the so-called Arab Spring, but what particularly caught my eye was the brutality the policeman and soldiers reserved for women and students in the crowd. It would be replayed a few months later in the scenes of cops beating and spraying with mace young women during the Occupy Wall Street demonstrations in our cities. One could feel the pleasure that inflicting pain gave these men and the hatred they bore for these disobedient children of their fellow citizens, as they worked up a sweat kicking and pummeling them. That’s why

I’m wary of the politicians and op-ed page writers who routinely

express shock

and outrage at the brutal treatment of demonstrators in other parts of

the

world. They never seem to notice how we treat them at home or how our

soldiers

deal with them in the countries we’ve been occupying lately. The

farther away

the injustice is, one might say, the louder their voices are, though

even there

they tend to be selective and preach humanitarian aid only when it

suits our

interests. If the regime doing the beating is one of our allies, not a

peep

will be heard from anyone in Washington. If not, than their usual

advice for

putting a stop to the mistreatment of protesters is military

intervention. To

hear someone like Senator John McCain tell it, all we need to do in

these

countries is drop a lot of bombs and freedom and democracy will emerge

from the

wreckage, as they did, I presume, in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya. He

and other

enthusiasts of military interventions have no patience with anyone who

argues

that it’s not up to us to remedy every injustice in the world, or who

points

out that, when we involve ourselves, we end up killing a lot of

innocent people

and unleashing ethnic and religious passions, resulting in local and

regional

chaos we have no way of containing. It is the

selective morality of our interventionists that offends me. They judge

acts of

violence not by their consequences, but on whether someone else or we

are the

perpetrators—if the acts are done by us they tend to have their full

approval.

Hypocrites who are blind or indifferent to their own country’s

atrocities are

not well suited for playing the part of moral conscience of the world,

especially when their claims to desire democracy in these troubled

countries

has a long and notoriously checkered history. As we have witnessed

again and

again, since we overthrew the elected government in Iran sixty years

ago, the

United States prefers to deal with countries run by autocrats and the

military,

because democracies that genuinely respond to the wishes of voters tend

to be

unpredictable and independent, and therefore are not in sync with our

strategic

and business interests. What a sigh

of relief for Washington when the Egyptian military overthrew the

democratically elected government! Overnight, the crowds that gathered

at

Tahrir Square were forgotten and the politicians and columnists who

idealized

them the day before fell silent, even as the army and the security

forces

started shooting them in the streets and locking them up by the

thousands. As

the saying goes, we have seen this movie many times before. There are

few

things that never change in this world of ours, but one of them happens

to be

the near certainty that those who raise their voices against injustice

get

betrayed in the end. March 21, 2014, 9:45 a.m. Bài viết này cũng có thể coi như lời ai điếu cho những kẻ đã tham gia biểu tình "phản chiến", Mỹ cút, Ngụy nhào, VC Bắc Kít vô lẹ lên, trên đường phố Sài Gòn ngày nào

Thầy Kuốc,

do có đọc điệc gì đâu, toàn phán nhảm. Đây là những vấn đề liên quan

đến chuyên

môn, phải là 1 sử gia, ít ra, thì mới dám đụng vô những vấn đề như vầy. Sử gia, ít

ra. Quả đúng như thế. Sử gia, giỏi lắm thì cũng chỉ rành quá khứ, những

gì xẩy

ra rồi. Phải là nhà văn, nhà thơ thì mới tiên đoán ra được chuyện sẽ

xẩy ra. Làm sao mà lại có 1 ông

như TTT, chưa từng ra nước ngoài, trước 1975, vậy mà tưởng

tượng ra 1 ông Mít bỏ chạy cuộc chiến, để rồi bò về để chết vì đạn của

Ngụy, vì

lầm ông là VC. Ghê nhất, là

trường hợp Kafka. Như Frédéric Beigbeder,

phán, Vụ Án còn là một thứ

chuyện

“Liêu Trai” có tính tiên tri (un fantasme prophétique), như rất nhiều

cuốn sách

khác ở trong Bảng Phong Thần Cuối

Cùng. Cuốn tiểu thuyết được in và xuất bản

vào năm 1925, nhưng Kafka đã viết nó mười năm trước, tức là năm 1914,

trước khi

có cuộc cách mạng Nga, Cuộc Đệ Nhất Thế Chiến, chủ nghĩa Quốc Xã Nazi,

chủ

nghĩa Stalin: thế giới được miêu tả ở trong cuốn sách, chưa hiện hữu,

chưa “đi

vào hiện thực”. Vậy mà ông nhìn thấy! Liệu có thể coi ông là Ông Thầy

Bói

Nostradamus của thế kỷ 20? Ở đây, là một

giả thuyết, nghe đến rởn tóc gáy lên được, và cũng hoàn toàn có tính

Kafkaien:

Liệu tất cả những trò kinh tởm của thế kỷ: chiến tranh lạnh, những

chuyện đấu tố,

luôn cả bố mẹ, hiện tượng con người có đuôi, lò thiêu, trại tập trung

cải tạo,

Solhzenitsyn, Orwell…. tất cả là đều nảy sinh từ cái đầu của một anh

chàng làm

cho một công ty bảo hiểm ở Prague? Liệu hàng triệu triệu con người chết

đó, là

để chứng minh cho sự có lý, của một cái đầu chứa đầy những ác mộng? (a) Mới đây nhất,

là trường hợp Ukraine. Cuộc trưng cầu dân ý vừa mới xẩy ra, mà, như 1

bạn đọc chỉ

cho thấy, Adam Zagajewski đã nhìn ra rồi, qua bài thơ post trên Tin Văn Ukraine held

a referendum Adam

Zagajewski: Myticism for Beginners Trưng cần

dân ý Ukraine tổ

chức trưng cầu dân ý Note: Người

rành về cú Ukraine, theo GCC, có vẻ là Do Kh, trên FB của anh. Nhưng,

như… GCC,

anh cũng chỉ đưa ra info, links.... Bạn đọc, đọc, rồi quyết định/tiên

đoán cho

riêng mình,1 kết thúc, 1 ngõ ra cho cuộc khủng hoảng. Tại LHQ, ĐS

Mỹ Samantha Power tiến đến chửi ĐS Nga Churkin, "Đừng có quên Nga là

nước

thua chứ không phải là nước thắng và phải tuân thủ Mỹ", nắm lấy tay ông

này khiến ông phải giật ra và bảo "đừng có văng nước bọt vào tôi"

:-))) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rnnI13Ynh0Y DS Mẽo tại

LHQ, Samantha Power, là tác giả cuốn “Một vấn đề từ Địa Ngục", "A

Problem

from Hell" (2002), TV đã giới thiệu. Putin’s

Counter-Revolution Ví dụ, năm

1956, hàng ngàn dân chúng, đặc biệt là giới sinh viên và trí thức, biểu

tình

trên các đường phố ở Budapest để chống lại một số chính sách của chính

phủ

Hungary. Một số sinh viên bị bắn chết. Làn sóng công phẫn trào lên, dân

chúng

khắp nơi lại ào ào xuống đường biểu tình. Đầu tháng 11, Liên Xô tràn

quân qua

biên giới Hungary để trấn áp những người biểu tình, giúp chính phủ cộng

sản độc

tài tại Hungary khôi phục lại quyền lực. Hơn 2000 người Hungary bị giết

chết.

Khoảng 200.000 người phải chạy ra nước ngoài tị nạn. Trước biến cố ấy,

Mỹ làm

được gì? Tổng thống Dwight Eisenhower chỉ làm được một việc duy nhất là

tố cáo

những hành động trấn áp dã man của Liên Xô trước Liên Hiệp Quốc. Hết. NHQ Trên TV đã từng

giới thiệu 1 số bài viết, cũng đã lâu lắm rồi, về cuộc cách mạng

Budapest mà phải

bao nhiêu năm sau, nhân loại mới nhìn ra thành quả của nó: Không có nó,

là

Stalin đã nhuộm đỏ cả Âu Châu rồi. NQT Có thể nhìn

thẳng vào cái chết, với hy vọng. Một cuộc cách mạng đạo đức. [Bìa báo Tin Nhanh, L'Express Inter, số đề ngày 19-25 Tháng Mười, 2006].

Trước biến cố ấy, Mỹ làm được gì? Tổng

thống Dwight Eisenhower chỉ

làm được một việc duy nhất là tố cáo những hành động trấn áp dã man của

Liên Xô

trước Liên Hiệp Quốc. Hết. NHQ Thầy Kuốc muốn Mẽo làm được gì?

Tổng Thống Mẽo thì là cái đéo gì ở

đây? Không lẽ ông ta cho lính Mẽo can thiệp vô Hung? Thầy chưa từng

nghe 1 tên

Bộ Trưởng Ngoại Giao Mẽo, James Baker, hình như vậy, (1) trả lời Thầy

ư:

Đếch có 1

con chó Mẽo nào kẹt ở đó hết! Viên bộ trưởng

ngoại giao Mỹ, James Baker, đã diễn tả thật là tuyệt vời, cái tính

"thực tế"

của chính sách trên, qua câu nói, khi xẩy ra những vụ nhổ cỏ thì phải

nhổ cả gốc,

làm sạch những sắc dân khác (ethnic cleaning) ở Bosnia: "Chẳng có một

con

chó Mỹ nào bị kẹt ở đó." (We don’t have a dog in this fight: Chúng ta

không có một con chó nào ở trong trận đánh này).

Bây giờ thì

khác. Khi Nga tấn công và chiếm đóng bán đảo Crimea của Ukraine, phản

ứng của Mỹ

khác hẳn. Vẫn không động binh. Nhưng cũng không phải chỉ đánh bằng võ

mồm. Tổng

thống Barack Obama tận dụng một thứ vũ khí mới, thứ vũ khí phi quân sự

(nonmilitary): kinh tế. Có thể nói, từ thời đệ nhị thế chiến đến nay,

trong tổng

số 12 tổng thống Mỹ đương đầu với những thử thách xuất phát từ Liên Xô

và sau

đó, Nga, Obama là một trong những người đầu tiên sử dụng vũ khí ấy. NHQ Chính trị thế

kỷ 21. Kinh thế. Tình hình

Crimée, cho tới bi giờ, cũng chưa ai biết nó sẽ ra sao. Thầy Kuốc cứ

làm như

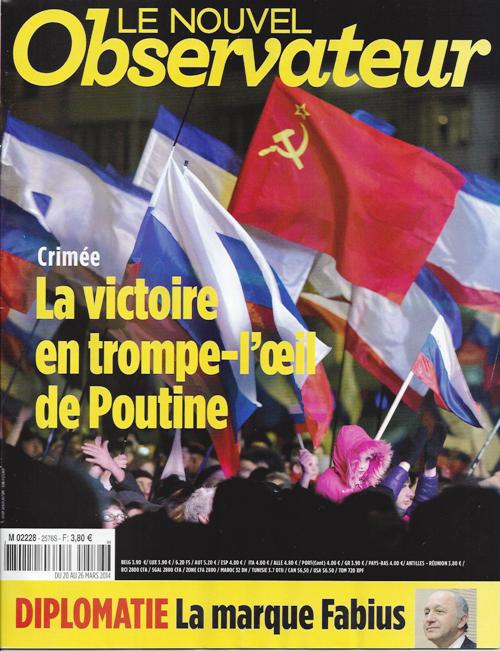

Obama nắm được tẩy của Putin, với vũ khí “kinh t[h]ế”. Bài mới nhất, trên tờ Obs, tuần lễ 20-26 Mars, 2014, thì coi như đây là chiến thắng tạm [trompe-l’oeil, đánh lừa con mắt], của Putin, khi cho biết, với người dân Crimée, đa số, nhất là giới trẻ, mừng quá, khi gia nhập Nga, tiền lương cao hơn, hưu nhiều hơn, hệ thống giáo dục ngon hơn. Còn tờ “Điểm Sách London”, 20 March, 2014, trong bài viết "Putin's Counter-Revolution", James Meek tường trình tại chỗ, thì coi đây là cú phản cách mạng của Putin, và cho rằng có 1 quãng cách, giữa lớp trẻ, và lớp già, ở Ukraine. Giống như tại Việt Nam, lớp trẻ, không biết 1 tí gì về tội ác, mà chỉ biết thành quả của VC, rất tức giận khi có những tên phản động chống lại nhà nước, như mấy bloggers mới bị nhà nước VC tống vô tù. Tờ “Người Nữu Ước” thì nói tới vũ khí kinh t[h]ế của Putin, hơi đốt [Ông ta có 1 thứ vũ khí không qui ước, unconventional weapon, trong kho của mình: vast supplies of natural gas]. Tờ này vờ luôn vũ khí "kinh t[h]ế" của Obama! Thầy Kuốc

đâu có đọc, mà làm sao…. đọc? Riêng với

Thanh Tâm Tuyền, bài thơ Budapest mà tôi đọc được, đã trụ lại trong tôi

suốt từ

bấy đến nay. Biến cố bi thảm ở Budapest năm 1956 mà truyền thông khắp

thế giới

đã nói đến rất nhiều bằng những từ ngữ rất mạnh mẽ, thì nhà thơ của

chúng ta đã

chỉ dùng hình ảnh của đôi trẻ để mô tả cuộc đàn áp dã man tàn nhẫn đó.

Mấy câu

thơ giản dị đã gây xúc động và còn lại mãi trong lòng người thưởng

ngoạn. Xin đừng

hỏi tôi bài thơ ấy hay ở chỗ nào. Chịu. Xin chịu. Tôi không có may mắn

được đào

tạo về những lý sự thế nào là hay thế nào là không hay và điều đó cũng

đã thành

thói quen trong tôi. Cho nên tôi chỉ cần thấy được cái nào hay là đủ.

Rồi về

sau, nhiều lúc, nhiều nơi (kể cả ở nhà tù) tôi đã gặp nhiều người cũng

rất

thích bài thơ đó. Có ai đó đọc lên một câu liền có người khác phụ họa

theo, chứng

tỏ bài thơ rất phổ biến. “Hãy cho tôi

khóc bằng mắt em, Hãy cho tôi

chết bằng da em, Thảo Trường: Tôi gọi tên tôi cho đỡ nhớ Những bình luận hay nhất, về đủ thứ vấn đề, cả về văn học, với GCC, là của tờ “Người Kinh Tế”. Tất nhiên, với tình hình Crimea, thì cũng thế. Số mới nhất có tới mấy bài viết về cơn khủng hoảng này: Dilomacy after Crimea: The new world order. The Crimea Crisis: Responding to Mr. Putin. Violence in Crimea. Thường là Gấu bỏ qua, chỉ đọc mấy bài điểm sách, hay mục do tay Prospero giữ, 1 thứ tạp ghi cực cao về văn học. Nhân cú “kinh thế” của Thầy Kuốc, bèn ghé mắt đọc sơ sơ cho biết! Tin Văn post

bài trên “Người Kinh Tế”, để chứng minh Obama quá ẹ. Mi không hành động

bi giờ

là sau này phải trả giá. Chẳng thấy khen Tông Tông Da Đen về vũ khí

"kinh t[h]ế"

của Người. The new world order The

post-Soviet world order was far from perfect, but Vladimir Putin's idea

for

replacing it is much worse. IN PEOPLE'S

hearts and minds," Vladimir Putin told Russia's parliament this week,

"Crimea

has always been an inseparable part of Russia." He annexed the

peninsula

with dazzling speed and efficiency, backed by a crushing majority in a

referendum (see page 22). He calls it a victory for order and

legitimacy and a

blow against Western meddling. The reality is that Mr. Putin is a force

for

instability and strife. The founding act of his new order was to redraw

a

frontier using arguments that could be deployed to inflame territorial

disputes

in dozens of places around the world. Even if most Crimeans do want to

join

Russia, the referendum was a farce. Russia's recent conduct is often

framed

narrowly as the start of a new cold war with America. In fact it poses

a

broader threat to countries everywhere because Mr Putin has driven a

tank over

the existing world order. The embrace of the

motherland Foreign

policy follows cycles. The Soviet collapse ushered in a decade of

unchallenged

supremacy for the United States and the aggressive assertion of

American

values. But, puffed up by the hubris of George Bush, this "unipolar

world" choked in the dust of Iraq. Since then Barack Obama has tried to

fashion a more collaborative approach, built on a belief that America

can make

common cause with other countries to confront shared problems and

isolate wrongdoers.

This has failed miserably in Syria but shown some signs of working with

Iran. Even

in its gentler form, it is American clout that keeps sea lanes open,

borders

respected and international law broadly observed. To that extent, the

post-Soviet order has meaning. Act now or pay later For Mr

Obama, this is a defining moment: he must lead, not just co-operate.

But Crimea

should also matter to the rest of the world. Given what is at stake,

the

response has so far been weak and fragmented. China and India have more

or less

stood aside. The West has imposed visa sanctions and frozen a few

Russians'

assets. The targets call this a badge of honor. At the very least, the

measures

must start to exceed expectations. Asset freezes can be powerful,

because, as

the Iran sanctions showed, international finance dreads being caught up

in America's

regulatory machinery. Mr Putin's kleptocratic friends would yelp if

Britain

made London unwelcome to Russian money linked to the regime (see page

25).

France should withhold its arms sales to Russia; and, in case eastern

Ukraine is

next, Germany must be prepared to embargo Russian oil and gas. Planning

should

start right now to lessen Europe's dependence on Russian energy and to

strengthen NATO. Ukraine needs short-term money, to stave off collapse,

and longer-term

reforms, with the help of the IMF, backed by as much outside advice as

the

country will stomach. As a first step, America must immediately pay its

dues to

the fund, which have been blocked by Congress for months. Even if the

West is

prepared to take serious measures against Mr Putin, the world's rising

powers

may not be inclined to condemn him. But instead of acquiescing in his

illegal annexation

of Crimea, they should reflect on what kind of a world order they want

to live

under. Would they prefer one in which states by and large respect

international

agreements and borders? Or one in which words are bent, borders ignored

and

agreements broken at will? • Tuần rồi, Vladimir

Putin bảo Quốc hội Nga rằng: “Trong tâm tư người dân, Krym mãi là một

phần

không thể tách rời Nga.” Và thế là Putin đã sáp nhập bán đảo Krym vào

Nga với

tốc độ và cách làm hiệu quả đến chóng mặt, với sự hậu thuẫn của đa số

áp đảo

qua trưng cầu dân ý. Putin gọi đó là thắng lợi của trật tự, của chính

danh, và

là một đòn đau đánh vào bàn tay thập thò can thiệp từ phương Tây. Nhưng, coi vậy mà

không phải vậy, Putin không đại diện cho trật tự mà đại diện cho bất ổn

và đấu

đá. Việc đầu tiên Putin làm để đặt nền móng cho trật tự mới là vẽ lại

đường

biên giới dựa trên những lý lẽ tuỳ tiện, những lý lẽ rất dễ bị lợi dụng

để thổi

bùng ngọn lửa tranh chấp lãnh thổ tại hàng chục nơi khác trên thế giới.

Thêm

nữa, dù hầu hết người Krym muốn theo Nga, cuộc trưng cầu dân ý vừa rồi

cũng chỉ

là một trò hề. Hành xử của Nga gần đây thường được dư luận gán cho một

cách

phiến diện rằng đó là khởi đầu cho một cuộc chiến tranh lạnh mới giữa

Nga và

Mỹ. Thực ra, hành xử đó đặt ra một đe doạ rộng lớn hơn, và là đe doạ

cho bất cứ

quốc gia nào ở bất cứ đâu, vì Putin vừa ngang nhiên lái xe tăng, cán

bừa rồi

ngồi chồm hổm trên trật tự thế giới hiện có. Đất mẹ xiết vào

lòng Chính sách đối

ngoại thường đi theo chu kỳ. Chế độ Xô-viết sụp đổ mở đường cho một

thập niên

thống trị vô đối của Mỹ và sự khẳng định rình rang những giá trị Mỹ.

Nhưng thế

giới “duy ngã độc tôn” này, được thổi phồng lên bằng sự ngạo mạn vô lối

của

George Bush, đã phải hụt hơi ngạt thở trong khói bụi từ cuộc chiến

Iraq. Từ đó,

Barack Obama đã tìm cách đưa ra một đường lối đa phương hơn, có người

có ta

hơn, xây dựng trên niềm tin rằng Mỹ có thể đứng chung chiến tuyến với

các nước

khác để đương đầu với những vấn nạn chung và để cùng nhau cô lập kẻ ác.

Đường

lối này thất bại thảm hại tại Syria, nhưng vẫn có dấu hiệu cho thấy

hiệu quả

khi áp dụng tại Iran. Tuy ảnh hưởng đã giảm nhưng phải nói rằng chính

uy thế

của Mỹ đã giúp cho đường hàng hải thế giới vẫn còn thông thoáng, các

biên giới

còn được tôn trọng và luật pháp quốc tế hầu hết được tuân thủ. Xét ở

mức độ đó thì

trật tự hậu Xô-viết rõ là có ý nghĩa của nó. Nhưng Putin đang

phá huỷ trật tự này. Ông cố khoác cho việc sáp nhập Krym chiếc áo luật

pháp

quốc tế, chẳng hạn như lập luận rằng việc loại bỏ chính quyền ở Kiev

vừa qua

khiến ông không còn bị trói buộc bởi thoả ước đảm bảo sự vẹn toàn lãnh

thổ

Ukraine, một thoả ước Nga đã ký năm 1994 khi Ukraine từ bỏ vũ khí hạt

nhân.

Nhưng luật pháp quốc tế chỉ có nghĩa khi chính quyền đến sau thực thi

những

quyền hạn và trách nhiệm được chính quyền trước trao lại. Chưa hết,

Putin còn

viện dẫn nguyên lý rằng phải bảo vệ “đồng bào” mình – tức tất cả những

ai ông

tự tiện gọi là người Nga – bất chấp họ đang ở đâu. Chưa hết, chứng cớ

một đường

miệng lưỡi một nẻo, Putin còn chối bay chối biến rằng binh lính mang

quân phục

không phù hiệu nắm quyền kiểm soát tại Krym không phải là lính Nga. Sự

kết hợp

quái gở của hai vế, một bảo vệ và một dối trá, quả là thứ công thức phù

thủy dễ

dùng để can thiệp vào bất cứ quốc gia nào có sắc dân thiểu số cư ngụ,

không cứ

là người Nga. Khi rêu rao những

chuyện ngụy tạo trắng trợn về bọn phát xít ở Ukraine đe doạ Krym, Putin

đã xem

thường nguyên tắc rằng: sự can thiệp ở nước ngoài chỉ nên dùng như biện

pháp

cuối cùng trong trường hợp có đại họa. Putin biện minh bằng cách viện

dẫn vụ

NATO đánh bom Kosovo năm 1999 như tiền lệ. Nhưng cần biết rằng vụ NATO

can

thiệp vào Kosovo chỉ diễn ra sau khi có bạo động dữ dội và Liên Hiệp

Quốc đã

phải bó tay sau bao nhiêu nỗ lực bất thành – và bất thành cũng vì Nga

cản trở.

Ngay cả trong trường hợp này, Kosovo cũng không như Krym bị sáp nhập

lập tức,

Kosovo chín năm sau đó mới ly khai. Trật tự mới kiểu

Putin, tóm lại, được xây dựng trên chính sách thôn tính phục thù, sự

trắng trợn

xem thường sự thật, và việc bẻ cong luật pháp cho vừa vặn với những gì

kẻ nắm

quyền lực mong muốn. Trật tự kiểu đó có cũng như không. Buồn thay, quá ít

người hiểu điều này. Rất nhiều quốc gia bực bội với vị thế kẻ cả của Mỹ

và với

Châu Âu thích lên lớp dạy đời. Nhưng rồi họ sẽ thấy trật tự mới kiểu

Putin còn

tệ hại hơn nhiều. Các quốc gia nhỏ chỉ có thể phát triển tốt trong hệ

thống

luật lệ công khai minh bạch dù chưa hoàn hảo. Nếu giờ đây nguyên lý

mạnh được

yếu thua lên ngôi thì họ sẽ có rất nhiều điều phải sợ, nhất là khi phải

đối phó

với một cường quốc khu vực hay gây hấn bắt nạt. Trong khi đó, các quốc

gia lớn

hơn, đặc biệt là các cường quốc đang lên trong thế giới mới, tuy có ít

nguy cơ

bị bắt nạt, nhưng không phải vì thế mà một thế giới vô chính phủ trong

đó không

ai tin ai sẽ không có tác động xấu với họ. Vì nếu ý nghĩa của các thỏa

ước quốc

tế bị chà đạp, thì Ấn Độ chẳng hạn sẽ rất dễ bị cuốn vào cuộc xung đột

vũ trang

với Trung Quốc vì vùng đất tranh chấp Arunachal Pradesh hoặc Ladakh.

Cũng vậy,

nếu việc đơn phương ly khai được chấp nhận dễ dàng, thì Thổ Nhĩ Kỳ

chẳng hạn sẽ

rất khó thuyết phục sắc dân Kurds trong nước mình rằng tương lai của họ

sẽ tốt

hơn khi họ chung tay xây dựng hòa bình. Tương tự, Ai Cập và Ả Rập Saudi

cũng

muốn tham vọng khu vực của Iran bị kiềm chế, chứ không phải được thổi

bùng lên

nhờ nguyên lý cho rằng người ngoài có thể can thiệp để cứu giúp sắc dân

thiểu

số Hồi giáo Shia sống khắp vùng Trung Đông. Ngay Trung Quốc

cũng cần nghĩ lại. Về mặt chiến thuật, có thể nói Krym đã đưa Trung

Quốc vào

tình thế khó ăn khó nói. Vì một tiền lệ về ly khai sẽ là lời nguyền rủa

đen

đủi, trong khi Trung Quốc hiện có Tây Tạng đang muốn ly khai; ngược

lại, nguyên

lý thống nhất đất nước lại là bất khả xâm phạm, trong khi Trung Quốc

hiện có

Đài Loan chưa thể thống nhất. Tuy vậy, về mặt chiến lược, quyền lợi của

Trung

Quốc rất rõ ràng. Nhiều thập niên qua, Trung Quốc tìm cách trỗi dậy

trong hòa

bình và lặng lẽ, tránh né một cuộc xung đột như nước Đức hung hăng đã

kích hoạt

chống lại nước Anh vào thế kỷ 19 để cuối cùng kết thúc trong chiến

tranh.

Nhưng, hoà bình trong thế giới của Putin lại là điều khó thành, vì bất

cứ thứ

gì cũng có thể trở thành cái cớ để động thủ, và bất cứ sự gây hấn tưởng

tượng

nào cũng có thể dẫn đến một màn phản công. Hành động trước hay

trả giá sau Đối với Obama, đây

là giờ phút quyết định: Obama phải thực sự lãnh đạo, thay vì chỉ hợp

tác. Nhưng

Krym không chỉ là việc của Mỹ, mà còn là của cả thế giới. Với những tai

họa

nhãn tiền, phản ứng của các nước đến nay nói chung đều yếu và manh mún.

Trung

Quốc và Ấn Độ hầu như chỉ đứng bên lề. Phương Tây thì áp đặt cấm vận

visa và

phong tỏa tài sản của một số phần tử Nga. Nhưng những phần tử bị nhắm

tới thì

lại coi đó là huy hiệu của danh dự. Ít nhất, việc trừng

phạt cũng cần bắt đầu cứng rắn hơn, vượt ngoài dự kiến hơn. Phong tỏa

tài sản

có thể tác động mạnh, vì như vụ cấm vận Iran trước đây cho thấy, giới

tài chánh

quốc tế rất sợ dính líu tới guồng máy luật lệ của Mỹ. Cũng vậy, các

quan tham

của Putin sẽ la lối ầm lên nếu nước Anh không cho London nhận đồng tiền

có liên

hệ với chế độ tại Nga. Pháp nên hoãn việc bán vũ khí cho Nga; và trong

trường

hợp phía đông Ukraine là nạn nhân kế tiếp của Nga, thì nước Đức nên sẵn

sàng

cấm vận xăng dầu và khí đốt Nga. Cần lên kế hoạch ngay bây giờ để giảm

mức lệ

thuộc của Châu Âu vào nguồn cung cấp năng lượng từ Nga và để NATO mạnh

hơn. Trong ngắn hạn,

Ukraine cần nhiều tiền để cứu vãn kinh tế khỏi sụp đổ, và cần nhiều cải

cách

dài hạn với giúp đỡ của IMF, cùng những tư vấn từ nước ngoài mà Ukraine

có thể

chấp nhận được. Để đi bước đầu tiên theo hướng này, Mỹ cần lập tức

thanh toán

các khoản nợ cho IMF, khoản thanh toán đã bị Quốc hội ngăn chặn nhiều

tháng

nay. Tuy nhiên, dù cho

phương Tây có sẵn sàng dùng những biện pháp cứng rắn chống Putin chăng

nữa thì

những cường quốc đang trỗi dậy vẫn có thể không mấy hứng thú trong việc

lên án

Putin. Nhưng, thay vì im hơi lặng tiếng trước vụ sáp nhập phi pháp

Krym, những

cường quốc đang trỗi dậy kia rất nên suy nghĩ xem họ đang muốn sống

trong một

trật tự thế giới như thế nào. Họ muốn một trật tự trong đó hầu hết các

quốc gia

tôn trọng những thỏa ước quốc tế và biên giới đã vạch? Hay là họ thích

một trật

tự trong đó cam kết bị bẻ cong, biên giới bị xâm phạm và thỏa ước cứ

thích là

xé? Nguồn:

“The new world order”, The Economist,

số ra

ngày 22/3/2014 Bản tiếng Việt ©

2014 Phan Trinh & pro&contra

Ví dụ, năm

1956, hàng ngàn dân chúng, đặc biệt là giới sinh viên và trí thức, biểu

tình

trên các đường phố ở Budapest để chống lại một số chính sách của chính

phủ

Hungary. Một số sinh viên bị bắn chết. Làn sóng công phẫn trào lên, dân

chúng

khắp nơi lại ào ào xuống đường biểu tình. Đầu tháng 11, Liên Xô tràn

quân qua

biên giới Hungary để trấn áp những người biểu tình, giúp chính phủ cộng

sản độc

tài tại Hungary khôi phục lại quyền lực. Hơn 2000 người Hungary bị giết

chết.

Khoảng 200.000 người phải chạy ra nước ngoài tị nạn. Trước biến cố ấy,

Mỹ làm

được gì? Tổng thống Dwight Eisenhower chỉ làm được một việc duy nhất là

tố cáo

những hành động trấn áp dã man của Liên Xô trước Liên Hiệp Quốc. Hết. NHQ Trên TV đã từng

giới thiệu 1 số bài viết, cũng đã lâu lắm rồi, về cuộc cách mạng

Budapest mà phải

bao nhiêu năm sau, nhân loại mới nhìn ra thành quả của nó: Không có nó,

là

Stalin đã nhuộm đỏ cả Âu Châu rồi. NQT Có thể nhìn

thẳng vào cái chết, với hy vọng. Phải đợi một

nửa thế kỷ, nhân loại mới tìm ra tên của nó:   Chuyện gì xẩy

ra tại Hung, vào năm 1956? Đây là tóm tắt

về nó, tại Tây Phương, trích Bách Khoa Toàn Thư Columbia Enclycopedia. Vào ngày 23

Tháng Mười, 1956, một cuộc cách mạng Chống Cộng của dân chúng, tập

trung tại

Budapest, bùng nổ tại Hungary. Một chính quyền mới được thành lập, dưới

quyền

Imre Nagy, tuyên bố Hungary trung lập, rút ra khỏi Hiệp Ước Warsaw, kêu

gọi LHQ

cứu trợ. Tuy nhiên, Janos Kadar, một trong những bộ trưởng của Nagy,

thành lập

một chính quyền phản cách mạng, và yêu cầu sự giúp đỡ quân sự của Liên

Xô.

Trong cuộc chiến đấu tàn bạo và quyết liệt, lực luợng Xô Viết dẹp tan

cuộc cách

mạng. Nagy và những bộ trưởng của ông bị bắt giữ và sau đó, bị hành

quyết. Chừng

190 ngàn người tị nạn rời bỏ xứ sở, Kadar trở thành thủ tướng, của chế

độ Cộng

Sản. * Ở trong căn

phòng của Lukacs, là ở trung tâm trận bão của thế kỷ chúng ta. Ông bị

quản thúc

tại gia, khi tôi tới gặp ông ở Budapest. Tôi thì còn quá trẻ, và sướt

mướt

không thể tin được, và khi tôi phải rời đi, nước mắt tôi ràn rụa: ông

bị quản

thúc tại gia còn tôi thì đi về với an toàn, với tiện nghi ở Princeton

hay bất cứ

một thứ gì. Tôi phải đưa ra một nhận xét nào đó, và sự khinh miệt hằn

trên

khuôn mặt ông. Ông nói, "Bạn chẳng hiểu gì hết, về mọi điều chúng ta

nói.

Trong cái ghế này, chỉ ba mươi phút nữa thôi, sẽ là Kadar," tên độc tài

đã

ra lệnh quản thúc tại gia đối với ông. * Trong những

lỗi lầm của Sartre, có vụ liên quan tới cuộc khởi nghĩa Budapest của

nhân dân

Hungary, vào năm 1956. "Một ô nhục", theo một tác giả trên tờ Le

Monde, vào năm 1996, khi Sartre "chấp thuận" (approuver) chuyện chiến

xa Liên Xô đè bẹp cuộc cách mạng. Trên tờ L’Express số đề ngày

9.11.1956,

Sartre, trong một cuộc phỏng vấn, trước tiên đã "kết án, không chút dè

dặt",

sự can thiệp của Liên Xô vào Hungary, coi đây là "một lỗi lầm không thể

tưởng

tượng được", "một tội ác"… nhưng cần phải đọc hết cuộc phỏng vấn. Lẽ dĩ nhiên,

quyết định của điện Cẩm Linh là "một lỗi lầm không thể tưởng tượng

được",

nhưng… "tất cả cho thấy rằng, cuộc nổi dậy "có chiều hướng phá huỷ

toàn bộ hạ tầng cơ sở xã hội". Đó là "một tội ác", nhưng…

"trong những nhóm người này, kết hợp nhằm chống lại những người Xô

Viết,

hoặc để đòi hỏi họ ra đi khỏi đất nước Hungary, người ta nhận ra, có

những

thành phần phản động, hoặc bị nước ngoài xúi giục"…. "sự có mặt (chứ

không phải hành động can thiệp thô bạo) của Liên Xô là "một điều cần

thiết"…. Lịch sử sau

đó cho thấy, nhân loại đã biết ơn rất nhiều ở cuộc cách mạng Hungary

vào năm

1956. Chính nhờ nó, mà Liên Xô nhận ra một điều, chuyện nhuộm đỏ cả Âu

Châu, là

một toan tính cần phải "xét lại". Ngay Sartre, trong cuộc phỏng vấn kể

trên cũng phải công nhận, lần đầu tiên có một cuộc cách mạng không mang

mầu đỏ

của phe tả (pour la première fois… nous avons assisté à une révolution

politique qui évoluait à droite). Tất cả những

khẳng định của Sartre đã được tờ Pravda đăng tải, cộng thêm những lời

ca ngợi

cuộc can thiệp của Hồng Quân, như của Janos Kadar, vào ngày 5 tháng 11.

Một

tháng sau đó, chúng trở thành những lời buộc tội những người cầm đầu

cuộc cách

mạng… Hãy cho anh

khóc bằng mắt em Hãy cho anh

khóc bằng mắt em Anh một trái

tim em một trái tim Hãy cho anh

giận bằng ngực em Hãy cho anh

la bằng cổ em Chúng nó say

giết người như gạch ngói Hãy cho anh

run bằng má em Lùa những

ngón tay vào nhau Hãy cho anh

ngủ bằng trán em Ðêm không

bao giờ không bao giờ đêm Hãy cho anh

chết bằng da em Anh sẽ sống

bằng hơi thở em Hãy cho anh

khóc bằng mắt em 12-56 Thanh Tâm Tuyền Thảo Trường

kể là, đám sĩ quan VNCH, đi tù VC, thơ TTT, mang theo, chỉ một bài này Note: Trên TLS số 5

Tháng

Chín, 2008, có bài điểm cuốn Một

Ngày Làm Rung Chuyển Thế Giới Cộng Sản. ONE DAY THAT SHOOK THE

COMMUNIST WORLD: The Hungarian-born

Austrian

journalist and historian Paul Lendvai has written a refreshingly

insightful

analysis of the 1956 Hungarian Uprising and its historical

significance. He

offers a fully updated critical discussion of one of the most

exhilarating and

hotly debated events in twentieth-century history. Drawing from

recently

released documents, Lendvai points out that the Hungarian Revolution

was

simultaneously an attempt to get rid of a decrepit Stalinist

dictatorship, and

a war for national liberation. Initially unwillingly, later more

determinedly,

Imre Nagy and his comrades engaged in a radical break not only with an

obsolete

system, but also with the Kremlin's imperialist ambitions. Bài

thơ Budapest của TTT, lần đầu

tiên ra mắt người đọc hải ngoại, và, cùng lúc, độc

giả ra đi từ Miền Bắc, thời gian Gấu, cùng với cả thế giới, kỷ niệm 40

năm cách

mạng Hung [1956-1996], qua bài viết Tạp Ghi, Hãy cho anh

khóc bằng mắt em, trên báo Văn Học, số tháng Ba, 1997, của

Nguyễn Mộng

Giác * Bất giác lại nhớ đến ngày 30 tháng Tư, chúng mày còn gì đâu mà đòi chuyện bàn giao, hoà giải, thành lập tân chính phủ....

Responding

to Mr Putin KHARKIVAND

KIEV Russia wants

a divided Ukraine, and despite the promise of the revolution it may

well get

one VLADIMIR

PUTIN, announcing the annexation of Crimea in the Kremlin's gilded Hall

of St

George, sounded like a victor who felt his place in history secure-

along with

Vladimir I, who adopted Christianity in Crimea, and Catherine the

Great, who

conquered it. Russia's political elite responded with thunderous

standing

ovations and tears and cheers for Russia. It was the

speech of a man whose ambitions go far beyond grabbing Crimea. But it

was not a

speech preparing the country for a lengthy or costly struggle. As Mr

Putin

pointed out with glee, Crimea was taken "without a single shot".

Fighting against the will of the people is difficult, if not

impossible, he

added. Mr Putin's

success in taking Crimea demonstrates his strengths-an ability to

appeal to

people's yearning for what they miss about the past, and a skill at

using the

legacies of that past to his own ends. He excels at deepening and

exploiting

existing weaknesses, and there is no shortage of such weaknesses in

Ukraine. Mr

Putin is right in saying that Ukraine's post-Soviet rulers busied

themselves

dividing the spoils, instead of building a state. It is understandable

that he

passes over Russia's persistent willingness to aid and abet them in

their

schemes. But that is precisely what February's Maidan revolution was

about. It

went beyond the overthrow of Viktor Yanukovych, the kleptocrat

president. It

was the birth of a Ukraine that is more than a geographical side-effect

of the

collapse of the Soviet Union, but instead a nation-state with its own

identity-a

nation that has outgrown its old politicians, but has yet to find a

responsible

elite to replace them. The rise in national consciousness can be

observed in a

steady flow of people-including Ukrainians for whom Russian is their

mother

tongue-enlisting as volunteers prepared to fight for their new country.

One of

them, Denis Shevlyakov, a 46-year-old Russian-speaker, says, "I dodged

military service in the Soviet Union; I never thought 1 would volunteer

to

fight for Ukraine." The will of the people Nobody knows what Mr Putin

will

do next. He probably realizes that Kiev, which he refers to as "the

mother

of Russian cities", is lost to him. But he will try to claw back what

he

considers to be part of the "Russian world"-a concept which has no

legal borders. If Ukraine implodes, as in its post-revolutionary

weakness it

might, he will pick off some pieces. The military threat remains. And

at the

very least he will insist on a deep federalization of Ukraine which

would allow

a de facto Russian protectorate in the southern and eastern parts of

the

country, and thus forestall any further movement towards the European

Union.

But Mr Putin's words about the impossibility of fighting the will of

the people

may yet come back to haunt him. Three factors allowed Mr Putin to annex

Crimea

easily and without bloodshed. The first was the power of the Russian

forces

already legitimately stationed in Crimea (it is not only home to

Russia's Black

Sea Fleet-there are several other military bases scattered across the

peninsula);

the second was the approbation of the ethnically and culturally Russian

population in Crimea, which has longed to regain its place as part of

the

Soviet empire. The third was the weakness of the interim government in

Kiev,

which was still being formed when Mr Putin struck. It was unable and

unwilling

to fight back in any way, and relieved to be restrained by Western

leaders

acutely aware that they could not step in to defend Ukraine themselves.

The

Ukrainian troops who defied the Russians in Crimea with dignity, if not

success, are heroes to their fellow countrymen. The government, though,

is seen

as having let them down. This could strengthen the hand of Ukraine's

right-wing

nationalists. Their mainstream party, Svoboda, has been losing support

sharply in

recent months, after a Nazi-style torch procession in January which

appalled

most Maidan supporters, but was a gift to Russian propagandists. Now

thugs from

Svoboda have harassed the head of Ukraine's national television channel

for

broadcasting Mr Putin's speech-providing Russian television with more

useful

footage. The

government has failed to counter Russian propaganda; for example, the

fact that

many of those gunned down on Independence Square by Mr Yanukovych's

snipers

were from the Russian-speaking east is not widely appreciated. This is

part of

a general failure to bring together the industrial east, where a

nostalgia for

the Soviet Union is still common, and the agricultural west, which is

more

individualistic and more keen on the European Union (see map). It took

Arseny

Yatseniuk, the prime minister, three weeks to make a televised appeal

to the

Russian-speakers in the south and east that reassured them about the

status of

their language and promised more autonomy for local governments. Things

might

have gone much better had the negotiations which produced the

government

included political leaders from the east and south in the first place. Street

theatre Russian

forces have been working to drive the different parts of the country

further

apart, using propaganda, agents of influence and provocateurs. Andriy

Parubiy,

a former Maidan leader who now heads Ukraine's National Security and

Defence

Council, says several Russian intelligence officers have been detained

in the

country. But despite some violent clashes in Donetsk and Kharkiv over

the past

week, encroaching on the east would not be as easy as it was in Crimea.

Valery

Khmelko of the Kiev International Institute of Sociology says that

although

people in the south and east of the country favor good relations with

Russia,

some 70 disapprove of Mr Putin being granted the right to use military

force in

Ukraine. The pro-Russian politicians who have emerged there are

marginal

figures who would not be able to control the region even if Moscow were

to move

in and install them as puppets. On the day of the Crime an referendum

pro-Russian separatists staged rallies in Donetsk and Kharkiv calling

for votes

there, too. Neither amounted to much. In Kharkiva couple of thousand

pro-Russian protesters gathered by the statue of Lenin (one of the few

left

standing) and listened to rather elderly activists before unfurling a

vast

Russian flag. The stand-off between the police and pro-Russian

protesters may

have aped Maidan, but it was not part of a mass movement, more a bit of

street

theatre, carefully choreographed for the cameras. By seven o'clock it

was all

over (which did not stop Russian television reporting "ongoing"

troubles

late into the night). Gennady Kernes, Kharkiv's mayor, says the rally

was

"illusion creation" designed as a possible justification for future

action. Russia does not need to move now, he says; it can afford to

wait until

the Ukrainian economy worsens, a process Russia is helping along by

blocking

Ukrainian exports. For his part, Mr Kernes, who has switched sides more

than

once over the past decade, says he recognizes the interim government

and

resents any talk of secession. The government distrusts him, but needs

his

support in the region-an ambiguity reflected in the fact that Mr

Kernes, as the

subject of a criminal investigation, is under night-time house arrest.

One of

the weakest links in the east is Donetsk, a coal-mining region

controlled by

Rinat Akhmetov, Ukraine's richest oligarch and Mr Yanukovych's

long-term political

partner. "He knows that any strong power in Kiev is a threat to him,"

one senior Ukrainian politician says. But he does not want to cede

control over

his region to Mr Putin, either. A federal structure and a fractious

parliamentary republic that would allow him to pull strings from behind

the

stage would suit him much better. Decentralization

is necessary; there is a consensus in Ukraine about giving more

economic

autonomy to elected mayors. Moving too far down the road to federalism,

though,

would make the desire of many to move the whole country into the

European

mainstream impossible (which is why Mr Putin likes the idea). Using Mr

Yanukovych as a legal instrument, the Kremlin has already refused to

recognize

the elections set for May 25th. If it manages to stop the ballot in the

south

and east of the country, or to cast doubt on 'its results, the new

Ukrainian

president will come to office crippled. If it foments violence, things

could

get very nasty, not least because Ukraine lacks motivated and

professional

security services. The police were, until a few weeks ago, fighting the

people now

in power; they are demoralized and distrusted. Some see them as a

source of

sabotage. Despite the threats, there is a chance that unity will

prevail. For

all its government failings and regional differences, support for

Ukraine's

sovereignty has grown steadily over the past two decades (see chart). A

generation has grown up with it and wants its children to enjoy it. As

Aanatoly

Gritsenko, a former defence minister, says: "We will never agree if we

think of Ukraine as the land of our fathers. But we can easily agree if

we talk

about Ukraine as the land of our children." + |