|

|

Linh tinh

Xưa,

khi cuốn: "Nỗi buồn chiến tranh" của nhà văn Bảo Ninh mới xuất bản, nó

như một luồng gió cho nền văn học viết về chiến tranh Việt Nam, mình có

mua 1 cuốn trước khi nó bị tịch thu và cấm phát hành. Mình đọc

Nỗi buồn chiến tranh của Bảo Ninh cũng thấy nó tản mạn, không liên tục,

không có tư tưởng lớn cho một dân tộc như, "Cuốn theo chiều gió" của

Magaret Michell của Mỹ, hay "Tiếng con chim hót trong bụi mận gai" của

Collin Mc Callaugh của Úc, etc... Một dân tộc lớn phải gắ... See More

Note: GCC tin là cái tay HH này, khùng, hoặc mù tịt về

văn học, khi so sánh Nỗi Buồn Chiến Tranh của Bảo Ninh, với Cuốn Theo Chiều

Gió và Tiếng Chim Hót Trong Bụi Mận Gai. Cuốn “Cuốn Theo Chiều Gió”, ghê

gớm như thế, nhưng với ngay cả tụi Mẽo, chúng cũng không coi là tác phẩm

văn học. "Tiếng chim hót", thì còn tệ hơn nhiều.

Con đường Mặc

Đỗ từ Hà Nội Sài Gòn tới Trưa Trên Đảo San Hô

Bài này, thấy

post ở, it nhất, thì cũng... ba diễn đàn!

Tuy nhiên,

không nơi nào nhận ra câu văn dưới đây, không chỉnh:

Sau ngày Chị

Mặc Đỗ mất, là một chấn thương lớn đối với anh, cả về tinh thần và sức

khoẻ.

Đúng ra, phải

viết, “cái chết của bà vợ là 1 chấn thương”, thí dụ, bởi, cụm từ “Sau

ngày chị

MD mất", không thể là chủ từ của “là” được. Lưu ý, chủ từ phải là 1

danh từ, cụm từ bắt đầu bằng "sau" [Sau ngày chị MD mất], coi như 1

trạng từ chỉ thời gian, không thể làm chủ

từ một câu văn.

Tuy nhiên vưỡn coi là được, kiểu viết tốc ký, vội,

nhưng

không chuẩn, theo nghĩa câu của Cioran, ta mơ 1 thế giới, ở đó,

người ta có

thể chết vì 1 cái dấu phẩy [đặt không đúng chỗ, GCC thêm vô]

Viết đã

không nên thân, mà nơi nào cũng khoe ra!

Y chang nhà

thơ y sĩ hải ngoại… nào đó!

Văn của Mặc

Đỗ rất khô, thành ra ít độc giả, theo GCC. Ông viết nhiều, nhưng với

Gấu, chỉ có

mỗi một truyện ngắn OK, kể câu chuyện 1 ông thầy tu đi thăm bịnh, là 1

cô

gái đang

bị sốt. Cả hai bèn cùng lên cơn sốt, bất chợt ông thầy tu nhìn thấy 1

con muỗi

đang đợp cái vai trần của cô gái, bèn giơ tay đập... Máu đỏ lòm

tay.

Nhìn thấy

máu, ông thầy tu bèn tỉnh lại, xém 1 tí là xuống địa ngục!

TTT đã từng chê nhân vật của MD, trong Siu Cô Nương, trí thức làm dáng.

Phải đến mãi sau này, khi TTT mất rồi, thì MD mới nhắc lại vụ này, khi

trả lời NTC (1)

GCC đã phán

rồi, nhiều tên viết 1 câu văn không nên thân mà có chừng cả tá đầu

sách, trong

khi bạn chỉ cần... 1 câu thôi.

Như Borges viết, thơ là

để trao cho thi sĩ.

Thơ thế, thì

văn cũng thế!

Viết thế nào, thì đọc thế đó, theo Gấu.

Một độc giả thứ thiệt, không ngửi được thứ văn này.

Mặc Đỗ với GCC, bảnh

nhất, là về dịch. Những dịch phẩm của ông, tên này cũng không nhớ được

nguyên tác,

và còn bỏ qua một cuốn cực bảnh, “Cuộc Tình Bỏ Đi”, tức “Tender is the

Night” của

Scott.

Bài viết chẳng có gì, chỉ là cơ hội để trưng mấy cái thư riêng, y

chang bài viết về TTT, trước đây.

Về Mặc Đỗ, mới

vừa đây, diễn đàn Gió O cũng viết về ông. Trong nước, thấy Blog NL cũng

có viết.

Giả như có nhắc tới, thì cũng cố nêu ra được 1 cái gì mới, ở Mặc Đỗ,

chưa được

ai phát hiện.

Viết kiểu này, thà đừng viết.

MD trên Gió O

MẶC ĐỖ

Trưa

Trên Đảo San

Hô

Malraux, còn lại gì?

Nghệ Thuật Làm Dáng

Chúng ta

luôn có dáng điệu của một kẻ sắp sửa ra đi, Camus viết như vậy. Một

Dũng của

"Bến Gió", của "sông Đà": kéo cổ áo cao lên một chút, tóc xổ

tung ra, mặc tình cho nó bù xù trước gió! Vũ Khắc Khoan, khi sinh thời

có kể một

huyền thoại về Nguyễn Tuân: Mặc áo gấm, nhảy xuống sông, thi bơi! Khi Siu Cô

Nương của Mặc Đỗ được

trình làng, Thanh Tâm Tuyền, trong một bài điểm sách, đã

coi, đây chỉ là những nhân vật làm dáng. Mặc Đỗ, sau đó, đã chỉ ra

những nét

làm dáng trong Ung Thư.

Ở đây, cứ coi như một "chân lý": không thể có

văn chương, nếu không có làm dáng. Nhưng đấy chỉ là khởi đầu, là thói

quen mút

ngón tay của con nít; sau đó phải là chấp nhận rủi ro, hiểm nguy, là

chọn lựa,

quyết tâm thực hiện thực tại "của những giấc mơ".

Vì bài viết

của Leys, chê Malraux, chỉ là 1 thứ trí thức làm dáng, mà Vargas Llosa

đi 1 đường

về Malraux, và về cái gọi là "Pantheon test".

Nhưng chính cái cú “cá

vưọt Vũ Môn”, hay Pantheon test, làm một số nhà văn mê mẩn, và nói quá

lên 1

chút, họ chưa ra đời là đã toan tính bịp thiên hạ, bằng chính cuộc sống

của

mình.

Rõ ràng nhất là trường hợp Romain Gary: Ông coi ông là “Second Coming”,

Chúa giáng sinh lần thứ nhì.

Phận Người

Không có ai

bảnh như một nhà văn nhớn trong cái việc làm cho chúng ta nhìn thấy

những

ảo ảnh.

[There is no one like a great writer to make us see mirages]. Malraux

không chỉ

làm được như vậy, khi viết, mà cả khi nói. Đây là 1 cái tài thiên bẩm

khác của ông

[another of his original gifts], một cái tài mà theo tôi, chưa từng có

tiền thân

cũng như hậu duệ [no precursors nor successors]. Tài ăn nói, oratory,

nhiều người

có, và là 1 thứ tài mọn, phiến diện, đầy những hiệu ứng âm thanh, hình

ảnh làm

nhàm, full of sonorous and visual effects, thường là rỗng tuếch, devoid

of

thought, thường được trình diễn cho/bởi những người ba hoa chích chòe.

Nhưng

Malraux là 1 tay ăn nói thần sầu, outstanding orator, như người ta có

thể nhận

ra, từ Oraisons funèbres [Funerary Orations],

ông là người có thể ban cho 1

bài diễn văn cả một rừng những tư tưởng mới mẻ, tươi rói, gây kích

thích, và

choàng lên chúng với những hình ảnh của một cái đẹp tu từ lớn lao. Một

số những

bài nói này, thí dụ bài diễn văn đọc tại Pantheon trước quan tài của

anh hùng

kháng chiến Pháp, Jean Moulin, hay trước quan tài Le Corbusier, tại sân

điện

Louvre, chúng là những mẩu văn chương tuyệt đẹp, và trong số chúng ta,

nếu có

người nào đã từng nghe, thì không thể nào quên được giọng nói hùng hồn,

như sấm

động, his thunderous voice, những quãng ngưng nghỉ rất ư là bi thương,

đúng thứ

vọng cổ Út Trà Ôn của Mít, và cái nhìn thiên sứ, his visionary gaze,

mới “Sến”

làm sao! Tôi đã có lần nghe ông đọc, từ xa, ở khu vực báo chí, vậy mà

còn run hết

cả người, mồ hôi lạnh toát ra như tắm, lông gáy dựng ngược, chỉ muốn

vãi linh hồn

[I heard them at a great distance, in the press pack, but I still went

into a

cold sweat and was very moved].

Malraux là

như vậy, suốt cuộc đời của ông: một cảnh tượng, a spectacle, và ông,

chính ông,

sửa soạn, điều khiển và trình diễn, prepared, directed, and performed.

Với kỹ năng,

thủ thuật của 1 bậc thầy, để ý đến, và không bỏ qua, dù 1 chi tiết nhỏ.

Ông

biết,

ta là 1 thằng cực kỳ thông minh, và sáng láng, và mặc dù vậy, ta đã

không trở

thành 1 tên ngu đần, [He knew that he was intelligent and brilliant

and, despite

it, he did not become an idiot]. Ông còn là 1 người can đảm, đếch sợ

chết, và bởi

vì điều này, thần chết ve vãn ông rất nhiều lần, ông bèn thừa

dịp để ôm

lấy nó, và đời của ông gồm rất nhiều cú “đẹp như xém chết” thế đó!

Và may mắn

làm sao, ông không là 1 tay đạo đức giả, hay vị kỷ, narcissistic, nhưng

là

1 tay trình

diễn đu bay, a high-flying exhibitionist (một Nam Tước Clappique) và

điều này

khiến ông vưỡn là người [that made him human], nghĩa là, lại khiến cho

ông thay

vì đi trên mây thì chân lại chạm đất, lại là 1 con người có sống có

chết, và điều

này làm Gide rất ư là ngỡ ngàng.

Rất nhiều nhà văn mà tôi biết, thất

bại trong

cái cú “cá vượt vũ môn” [Pantheon test], hay, sự diện diện của họ

ở đó, ở

cái Điện Thờ đó, hậu thế không thể nào chịu được, 1 cú sỉ nhục cho hồi

ức của họ.

Làm sao một Flaubert, một Baudelaire, một Rimbaud vô Pantheon? Nhưng

Malraux thì

lúc nào cũng có chỗ của ông ở đó. Không phải là tác phẩm của ông, hình

ảnh của ông

trở nên nghèo nàn hẳn đi giữa đống đá cẩm thạch, nhưng bởi vì ông mê

trò trình

diễn, một trong những thói đời đáng yêu của con người!

Làm sao mà

GCC quên nổi hình ảnh "trình diễn" của BHD, thí dụ, "nàng vội vàng chạy

vô rồi lại

vội vàng chạy ra, nàng quên không dặn chàng…" (1)

Hà, hà!

Cái đoạn đó,

1 anh bạn từ hồi đi học, mê quá, cứ ư ử hoài, sao mà mày sướng thế!

(1)

…. đang vội

vàng từ giã người yêu, vội vàng chạy vô cổng trường rồi lại vội vàng

chạy ra:

nàng quên không dặn chàng trưa nay đừng đón nàng, vì nàng sẽ về chung

với Lan

Anh, bạn nàng...

Note: Tiếp tục

“Bảng Phong Thần”, GCC sẽ giới thiệu bài viết của Vargas Llosa về cuốn Kẻ Xa Lạ [nhưng đếch phải Người Dưng]

của Camus, cùng lúc với một vài

bài viết khác, cũng về cuốn này. Cuốn sách tiếng Tây mà GCC đánh

vật với

nó, suốt một thời mới lớn, do tiếng Tây ăn đong!

Quái đản nhất, cái truyện

ngắn đầu tay của GCC, Những Con Dã

Tràng, đọc 1 phát, là lòi ra ngay một anh chàng Meursault Mít,

khật khừ, "húng hắng ho vào buổi chiều", và cái bãi

biển Nha Trang vào 1 mùa hè, ở giữa hai kỳ

thi Tú Tài

II, [kỳ 1 và kỳ 2], biến thành Địa Trung Hải, của Cà Mu!

******

Nabokov coi tác

phẩm lớn như chuyện thần tiên, nhưng phán như thế, chưa đủ. Những câu

chuyện thần

tiên như thế, phải có 1 điểm để bấu víu với cuộc đời. Theo nghĩa đó,

Lukacs,

phê bình gia Mác Xít thứ thiệt, mới bổ túc thêm, bằng cái cú tự mình đá

mình ra

khỏi Thiên Thai, la conversion finale, bằng cái “ý thức nhà văn vượt ý

thức

nhận vật”, nhà văn tìm lại đời sống thực, và đó là lúc Lưu Nguyễn về

trần.

Cả cuốn Con Đường Vương Giả, của

Malraux, chỉ để diễn ra cái

giây phút "thực", "làm đếch gì có cái

chết,

mà chỉ có ta, ta, ta đang... chết" Cái câu “Anh yêu em yêu quê

hương vô

cùng", sến ơi

là sến làm cho cuộc sống ngất ngư, chân không chạm đất, của "Tâm Hà

Nội, Tâm Bếp

Lửa, Tâm 1954"... trở thành thực.

Cũng vẫn

theo nghĩa đó, Borges gọi là nhà văn là "kẻ mơ ngày", hắn ta sống hai

cuộc đời, hai

thực tại, hai cõi, cõi này, và, cõi khác.

Bài Tạp

Ghi

"Chữ Người Tử Tù", Gấu viết về Nguyễn Tuân, khi gửi cho Văn Học, ông

chủ chi địa NMG, đọc, “bèn” gật gù, ông "sáng tác" bằng Tạp Ghi, tôi

đếch

viết được như ông! (2)

*****

Cuộc đời của

Malraux mới khốc liệt, đa dạng, mâu thuẫn, và có thể giải thích bằng

nhiều đường hướng, mâu thuẫn, chỏi lẫn nhau. Nhưng, không nghi ngờ chi,

cuộc đời

của ông bày ra [offer] một sự kết hợp tuyệt vời của tư tưởng và hành

động, ở mức “đỉnh của đỉnh”, bởi vì trong khi tham dự, gia nhập những

biến

động, những thảm họa long trời lở đất của thời của ông, thì, cùng lúc,

ông còn

là 1 con người được trời phú cho thông minh cực thông minh, sáng suốt

cực sáng suốt, và, chưa kể ở trong ông còn cái mầm sáng tạo, nhờ thế,

ông vẫn giữ

cho mình được 1 khoảng cách với biến động, với kinh nghiệm sống thực,

và chuyển

nó thành suy tư, thành chiêm nghiệm phê bình, hay những giả tưởng thần

sầu.

Có 1 dúm nhà văn, như ông, những người đồng thời với ông, hoàn toàn

trực tiếp

tham dự biến động, lịch sử: Orwell, Koestler, T.E. Lawrence. Cả ba ông

này đều

viết những tiểu luận thần sầu về cái thực tại bi đát mà họ sống ở trong

nó, nhưng

chẳng có ai tóm bắt được nó, và chuyển hóa nó thành giả tưởng một cái

tài năng như

Malraux.

Note:

Nhận xét của

Vargas Llosa, về T.E. Lawrence, GCC không có ý kiến, vì chưa từng đọc

ông này, nhưng

về Koestler và Orwell, sai.

Malraux chưa từng có tác

phẩm giả tưởng nào vươn tới

đỉnh như Trại Loài Vật, và Đêm Giữa Ban Ngày, chúng là những

giả tưởng đánh động

lương tâm của con người, trước thảm họa. Cái sự thực – hay dùng chữ của

Vargas

Llosa, cái thực tại bi đát mà họ sống, và từ chiêm nghiệm, và từ đó, đẻ

ra giả

tưởng, cũng khác nhau.

TTT, rất mê Malraux, và đã để 1 nhân vật của ông

thốt ra

câu ‘dưng không trồi lên sự thực’, cái sự thực dưng không trồi lên này

đúng là “cũng”

của cả TTT và Malraux.

Tác phẩm của TTT mà chẳng

từ sự thực thời của

ông ư?

Không

có Hà Nội, 1954, và cuộc di cư khủng khiếp, làm sao có Bếp Lửa?

Nhưng Bếp Lửa là

của TTT, trong đó, ngoài những sự kiện lịch sử trên, còn có 1 anh chàng

Tâm ngất

nga ngất như, khật khà khật khừ, của riêng TTT.

Applebaum nhận

ra điều này, khi phán về Trại Loài

Vật và Bóng Đêm:

Thiếu, chỉ 1 trong hai cuốn,

là cả Âu Châu bị nhuộm đỏ.

Tuyệt!

Malraux, TTT

không có thứ tác phẩm đó.

Bản thân GCC,

nếu những ngày mới lớn, không được chích 1 mũi thuốc ngừa VC – không

đọc Bóng Đêm

Giữa Ban Ngày – chắc chắn đi vô rừng, vô bưng, làm đệ tử Hoàng

Phủ Ngọc

Tường, và biết đâu, tay cũng đầy máu rồi.

Vị trí của

Malraux, trong lịch sử thời của ông, chưa khủng bằng của Koestler, như

Steiner

phán trong bài viết tưởng niệm ông, La

Morte d’Arthur:

Koestler,

sinh năm 1905, ở Budapest, đứng đứng chỗ của những chấm dứt cân não của

thế kỷ

20 -lịch sử, chính trị, ngôn ngữ, và khoa học - đụng vô.

K [….] stood

on the exact terrain where the nerve ends of the 20th century history,

politics, language, and science touch.

Trong 1

bài

viết về Steiner, VL cho biết, rất mê cuốn Ngôn ngữ và Câm lặng của ông, nhưng

sau cuốn đó, hết đọc được Steiner, và gọi ông là 1 thứ enfant terrible

của thế

kỷ.

Theo GCC,

Vargas Llosa không có được sự thâm hậu, và cùng lúc, không có được nỗi

đau… Lò Thiêu, nên không đọc nổi Steiner.

****

V/v giả đò, làm dáng, bịp…

Cynthia Ozick, trả lời phỏng vấn,

"Cuốn sách thay đổi đời tôi", cho biết, đó là cuốn Washington

Square, của Henry James.

Bà viết:

Một bữa, khi tôi 17 tuổi, ông anh mang về nhà một tuyển tập những câu

chuyện bí

mật, mystery stories, trong, lạ lùng sao, có truyện The Beast in the

Jungle của

Henry James. Đọc nó, tôi có cảm tưởng đây là câu chuyện của chính đời

tôi. Một

người đàn ông lớn tuổi, đột nhiên khám phá ra, ông bỏ phí đời mình hàng

bao năm

trời.

Đó là lần đầu tiên Henry James làm quen với

tôi. Washington Square tới

với tôi muộn hơn. Câu chuyện của cô Catherine được kể một cách trực

tiếp, cảm

động, và gây sốc. Đề tài xuyên suốt tác phẩm này là: Sự giả đò. Giả đò

làm một

người nào đó, mà sự thực mình không phải như vậy. Ở trong đó có một ông

bố tàn

nhẫn, ích kỷ, giả đò làm một người cha thương yêu, lo lắng cho con hết

mực. Có,

một anh chàng đào mỏ giả đò làm người yêu chân thành sống chết với

tình, một bà

cô vô trách nhiệm, ngu xuẩn, ba hoa, nông nổi giả đò làm một kẻ tâm sự

ruột,

đáng tin cậy của cô cháu. Và sau cùng, cô Catherine, nạn nhân của tất

cả, nhập

vai mình: thảm kịch bị bỏ rơi, biến cô trở thành một người đàn bà khác

hẳn.

Ozik cho rằng, ý tưởng giả đò đóng vai của

mình, là trung tâm của cả hai vấn

đề, làm sao những nhà văn suy nghĩ và tưởng tượng, và họ viết về cái

gì. Không

phải tất cả những nhà văn đều bị vấn đề giả đò này quyến rũ, nhưng, tất

cả

những nhà văn, khi tưởng tượng, phịa ra những nhân vật của mình, là

khởi từ vấn

đề giả đò, nhập vai.

Tuy nhiên, nguy hiểm khủng khiếp của vấn đề

giả đò này là:

Những nhà văn giả đò ở trong đời thực, sẽ không thể nào là những nhà

văn thành

thực của giả tưởng. Cái giả sẽ bò vô tác phẩm.

[Writers who are impersonators in life cannot be honest writers in

fiction. The

falsehood will leach into the work].

Đây là

đòn Kim Dung gọi là Gậy ông làm

lưng ông!

Nhà văn giả đò, nhà văn dởm, nhà văn đóng vai nhà văn... Thứ này đầy

rẫy trong

văn chương Mít.

*

Gấu đọc Washington Square khi còn Sài Gòn, và bị nó đánh cho

một cú

khủng khiếp, ấy là vì cứ tưởng tượng, sẽ có một ngày, bắt cóc em BHD ra

khỏi

cái gia đình có một ông bố tàn nhẫn, ích kỷ, đảo ngược cái cảnh tượng

thê lương

ở trong cuốn tiểu thuyết:

Khi ông bố không bằng lòng cho cô con gái kết hôn cùng anh chàng đào

mỏ, cô gái

quyết định bỏ nhà ra đi, và đêm hôm đó, đợi người yêu đến đón, đợi

hoài, đợi

hoài, tới tận sáng bạch...

Và Gấu nhớ tới lời ông anh nhà thơ

phán, mi yêu thương nó thì xách cổ nó ra khỏi cái gia đình đó, như vậy

là may

mắn cho cả nó và cho cả mi!

Ôi chao giá mà Gấu làm được chuyện tuyệt vời đó nhỉ.

Thì đâu thèm làm Gấu nhà văn làm gì!

Thất bại làm người tình đích thực của BHD, đành giả đò đóng vai Gấu nhà

văn.

Thảm thật!

*

Kỳ tới Gấu sẽ cho trình làng, hai ông giả đò, một của thế giới, và một,

của

Mít.

Ông Mít này, đẻ ra một cái, là đã giả đò đóng vai [nhà văn dởm] của

mình rồi!

(1)

Trên Tin Văn, Gấu nhớ là đã có viết về 1 truyện ngắn của Somerset

Maugham, kể

câu chuyện 1 anh bồi bàn, sau được 1 bà góa chồng thương, lấy làm

chồng, và trở

thành bá tước, như ông chồng đã mất của bà này. Thế là anh ta cũng nhập

bá tước,

cư xử như… bá tước, và 1 bữa, cháy nhà,

cả hai vợ chồng bỏ chạy ra ngoài, thoát, nhưng ông bá tước dởm lừng

lững, khốc

liệt [thuổng Kiệt, trong MCNK] trở vô nhà, để kíu con chó.

Một vị bá tước

là phải như thế! Giống như vị thuyền trưởng, phải chết theo tầu!

Linh Tinh

Bài của

Likhachev, “Phẩm tính trí thức”, là bài rất có ích cho các nhà văn. Tôi

đặc biệt

chú ý đến đoạn nói về cách sống và phong độ của giới trí thức Nga, cũng

như đoạn

về nhà văn Solzhenitsyn. Không trách gì nhiều nhà văn nước ta (chứ

không phải

là nhà văn “ở ta”) trước đây mê văn học Nga đến thế. Mà mê là đúng, vì

họ lớn

quá. Sang trọng. Tôi thiết nghĩ các nhà văn gốc miền Nam

và ở hải ngoại nên tìm đọc thêm về văn học và lý luận văn học Nga. Biết

bao

nhiêu điều để học, sao cứ đọc hoài Frost với lại Faulkner? Tuy nhiên

theo thiển

nghĩ của tôi, sự phân chia hướng Âu hay Á-Âu thật ra không quan trọng

lắm.

Điềm

Trong nước mà

biết khỉ gì về Solzhenitsyn? Nhưng thôi, kệ mẹ tên khốn này lo thổi đít

VC.

Có điều

hắn phán, sao cứ đọc hoài về Frost với lại Faulkner, làm Gấu buồn cười.

Hải ngoại

nào đọc hoài hai đấng này, ngoài trang Tin Văn? Đọc 1 phát, là thấy rõ

tên này

tính cà khịa với GCC!

Gấu với hắn đâu có gì hận thù, nếu không muốn nói, là cũng

thuộc loại có quen biết, như dã từng viết.

Mà đâu phải

ra đến hải ngoại Gấu mới viết về Faulkner. Trong truyện

ngắn,

viết sau khi thằng em tử trận, "Mộ Tuyết", sau đưa vô

"Hai mươi

năm văn học Miền Nam", của Nguyễn Đông Ngạc, Gấu đã vinh danh Thầy của

mình rồi:

Khi anh định

viết về những chuyện đó, chắc là anh đã lập gia đình (đã yêu thương một

người

đàn bà), đã có con (đã có hai con, một trai, một gái), và như một kinh

nghiệm của

một nhà văn nước ngoài mà anh đã đọc và ngưỡng mộ (W. Faulkner), khi

đó, bởi vì

anh cần chút tiền để trả chút nợ, hay để mua cho vợ anh một chiếc áo

mới nhân dịp

sinh nhật, mua đôi giầy, đôi dép cho hai đứa nhỏ, chỉ vì chút nhu cầu

tầm thường

đó mà anh viết. Tất cả những nhu cầu nhỏ mọn chẳng liên quan gì đến văn

chương,

và cũng chẳng liên quan gì tới những nỗi đau khổ mà gia đình anh đã

trải qua

đó, đã xui khiến anh viết, đã cho anh thêm chút can đảm để bỏ một cuộc

vui, một

cuộc tụ tập với đám bạn bè nơi nhà hàng, quán nước (cái không khí túm

năm tụm

ba đó lúc nào mà chẳng toát ra một vẻ quyến rũ), đã cho anh thêm một

chút sức mạnh

để chống lại những giấc ngủ lết bết, chống lại sự lười biếng làm tê

liệt mọi dự

tính: anh sẽ viết về những gì thật nghiêm trang (những cái gì từa tựa

như là là

ý nghĩa về đời sống, cái chết, chiến tranh...) chỉ vì những nguyên nhân

thật tầm

thường giản dị, và đem tập bản thảo đi gạ bán cho một nhà xuất bản.

Bây giờ nhớ

lại, thì lại nhớ ra, lần đầu chỉ là 1 mẩu, đăng trên phụ trang VHNT

cuối tuần của

tờ Tiền Tuyến, thời gian TTT còn phụ trách, và bị ông anh nhắc nhở, cái

mục của

mày, là chỉ để lo phê bình, điểm sách, giới thiệu tác phẩm mới xb, đừng

viết cái

gì khác thế vô.

Nhớ luôn, lần ở Trại Tị

Nạn Thái Lan, có được cuốn của Nguyễn Đông Ngạc, nhờ nó qua được thanh

lọc, một

bà cũng tập tành viết lách, hỏi mượn đọc,

sau đó nói với 1 bà bạn khác, truyện như thế mà "hay nhất của quê hương

chúng ta" ư?

[Cuốn của Ngạc còn có cái tên, “Những truyện ngắn hay nhất của quê

hương chúng

ta”]: Thằng em trai chết, mà tìm không thấy 1 giọt nước mắt!

Cái ý, "cần tiền

mua mấy cái tã cho con, bèn viết, và sau đó đem tác phẩm đi gạ bán", là

thuổng của

Faulkner.

Về cái gọi là

thơ hải ngoại, hay nói rõ 1 một chút, căn bịnh trầm kha của nó, của thơ

Mít, GCC nhận ra từ

khuya rồi,

và cố chữa trị, qua mục thơ mỗi ngày, tức là dịch, giới thiệu

thơ thế

giới.

Thơ Mít, ngoài thứ, phải có máu, của Bắc Kít, thì còn có, thơ

của

Miền Nam quy vào hai món, thơ tán gái, thơ ngồi bên ly cà phê nhớ bạn

hiền, bạn

quí.

Nếu không dịch thơ thế giới là còn khổ với Thầy Kuốc, cứ mỗi lần viết,

là lại bèn đọc chơi vài bài

ca

dao, vài bài tiền chiến!

Tay này khủng thật, vốn liếng chỉ có thế mà dám đi cả

1 cuốn sách về thơ, nhìn cái đéo gì thì qua góc độ thơ!

Bài viết dài

thòng của tên khốn này, thì cũng tệ hại như vậy, đó là sự thực.

Vậy mà hắn cho đăng

trên 3 diễn đàn, Da Mùi, Văn Học Vịt, rồi Văn Vịt!

Tởm

thật.

Điềm

11.8.2007

Nguyễn Đức Tùng

1. Bài của Likhachev, “Phẩm tính

trí thức”, là bài rất có

ích cho các nhà văn. Tôi đặc biệt chú ý đến đoạn nói về cách sống và

phong độ

của giới trí thức Nga, cũng như đoạn về nhà văn Solzhenitsyn. Không

trách gì

nhiều nhà văn nước ta (chứ không phải là nhà văn “ở ta”) trước đây mê

văn học

Nga đến thế. Mà mê là đúng, vì họ lớn quá. Sang trọng. Tôi thiết nghĩ

các nhà

văn gốc miền Nam

và ở hải ngoại nên tìm đọc thêm về văn học và lý luận văn học Nga. Biết

bao

nhiêu điều để học, sao cứ đọc hoài Frost với lại Faulkner? Tuy nhiên

theo thiển

nghĩ của tôi, sự phân chia hướng Âu hay Á-Âu thật ra không quan trọng

lắm.

2. Nhận xét của nhà văn Nguyên Ngọc về tuyên bố của Bộ

trưởng Thông tin-Truyền thông rất chính xác, thẳng thắn, mà vẫn có ý vị

văn

chương. Tôi rất thích đoạn ông bắt bẻ về vụ mười chữ và năm từ. Thật ra

từ vẫn

gọi là chữ được, vì từ hay chữ chỉ là qui ước của các nhà ngữ pháp sau

này

thôi, chứ lúc tôi còn đi học không có sự phân biệt đó. Vấn đề chính là,

đúng

như Nguyên Ngọc nói, nói năm từ hay chữ (đôi) thì đúng hơn là nói mười

chữ.

Mười chữ đơn lẻ không có nghĩa gì cả. Tôi nhớ trước ngày 30 tháng 4 năm

75,

ngồi bên radio nghe

Tổng thống Nguyễn Văn Thiệu đọc diễn văn, tôi đánh bạo nói với cha tôi

rằng

(thì là) theo nhận xét của một học sinh như tôi thì diễn văn của tổng

thống có

vẻ không đúng với văn phạm tiếng Việt mà tôi được học chút nào. Cha tôi

nhìn

tôi im lặng một lát rồi buồn rầu bảo, đại ý, các chính thể đến giờ phút

lụi tàn

bao giờ cũng có những biểu hiện như thế.

3. Nhờ cái link của talawas mà tôi cũng đọc được bài “ Hồ

Anh Thái có sợ giải thiêng?” trên VietNamNet nói về tác phẩm Đức Phật,

nàng

Savitri và tôi. Cuốn này có trích đăng trên talawas chủ nhật,

tôi chưa

kịp đọc,

nhưng Hồ Anh Thái thì tôi có đọc qua một hai cuốn khác vì bạn bè

khuyên. Tôi

cũng chưa đọc Phạm Xuân Thạch bao giờ, không biết ông có ký tên nào

khác không,

hay chỉ vì tôi ít đọc các nhà văn trong nước. Bài của ông làm tôi ngạc

nhiên

quá: tôi lấy làm mừng cho nền phê bình văn học Việt Nam.

Ít ra cũng phải có những bài

review mạnh mẽ, thuyết phục, khen chê rõ ràng như vậy. Thường thì các

nhà phê

bình Việt Nam

chỉ khen các nhà văn nhà thơ chứ không chỉ ra được cho họ các khuyết

điểm nghệ

thuật cần tránh.

Xin cám ơn La Thành, Nguyên Ngọc, Phạm Xuân Thạch, và Ban

biên tập talawas.

Nguồn

Bạn, đọc 1

cái "viết" của tên này, trên talawas, thì phải hình dung ra, đây là 1

đấng cực kỳ

"bố chó xồm" của hải ngoại, ông tiên chỉ VP cũng không có được thứ văn

phong hách

xì xằng như trên!

Thực tế, có ai biết hắn là thằng nào đâu.

Vậy mà, 40

năm thơ ca ở hải ngoại.

Cũng được đi,

nhưng đọc, như kít, cái đó mới khốn nạn.

Trích dẫn,

toàn những tên quen biết của hắn, cũng là 1 cách kéo bè kéo đảng.

Tếu nhất,

là, khi bị độc giả talawas nhẹ nhàng nhắc nhở, hắn sorry, "Tôi quên mất

tâm lý dễ bị tổn thương ở một vài người." [Nguồn

talawas].

Vẫn cái giọng

thổi đít VC!

Ấn tượng nhà vệ sinh ở Lào

TT - Tôi

vừa cùng một đoàn cán bộ hưu trí tham gia hành trình xuyên Đông Dương

cả tuần lễ và thấy thật ấn tượng với nhà vệ sinh ở Lào, chỗ nào cũng

khá tươm tất.

Nhà vệ sinh ở Lào có trang bị

máy lạnh, hoa, nến thơm...

Ảnh: N.V.M.

Lần đầu xuyên Lào, trong đoàn

nhiều người ngạc nhiên. Cứ tưởng nước họ nghèo hơn mình nên lạc hậu. Mà

họ nghèo hơn mình thật. Không thấy các cao ốc, dinh thự, trụ sở hoành

tráng. Đường hẹp nhưng ít xe nên tha hồ chạy. Các thị xã ở Lào xe hơi

nhiều hơn xe gắn máy nhưng không nghe tiếng còi xe. Cuộc sống bình

lặng, hiếu hòa, chậm rãi...

Tôi đến Lào nhiều lần nhưng ba năm nay mới trở lại. Có quá nhiều bất

ngờ. Người Việt mở nhà hàng ăn uống rất thành công ở Vientiane như nhà

hàng Đồng Xanh (chủ nhân người Đồng Tháp) và nhà hàng Hoàng Kim (chủ

nhân người Hà Nội) có nhiều món ngon và lúc nào cũng tấp nập khách. Dao

Coffee của doanh nhân Đào Hương (Việt kiều Lào) là đặc sản rất được du

khách ưa chuộng.

Tuy nhiên ấn tượng nhất của chuyến đi với đoàn là nhà vệ sinh ở Lào,

chỗ nào cũng khá tươm tất, có nơi chưa đẹp nhưng sạch sẽ. Du khách

chẳng sợ nạn “khủng bố tinh thần” vì thiếu chỗ giải quyết đầu ra trầm

kha như Việt Nam, đặc biệt là ở các tỉnh phía Bắc.

Sau khi khám phá động Tam Chang, đoàn ghé ăn trưa tại nhà hàng Manichan

ở Vang Veng. Nhà hàng thoáng đãng, trang trí bắt mắt, không có máy lạnh

mà trời thì nóng.

Chủ nhân nhà hàng giải thích:

“Nếu gắn máy lạnh phải xử lý mùi thức ăn rất cực. Hương vị các món ăn

sẽ không còn nguyên chất nên khó mà thưởng thức món ngon trọn

vẹn”.

Nhà vệ sinh bên ngoài xinh xắn, cạnh cây nhãn cổ thụ, có sẵn mấy ghế

bành nhỏ để khách ngồi hóng mát và đọc báo sau khi đi vệ sinh. Vào nhà

vệ sinh giữa trưa mà mát rượi, phảng phất mùi trầm như ở khách sạn 5

sao. Thì ra nhà vệ sinh gắn máy lạnh.

Mấy bồn tiểu nam đều có nến thơm lung linh khử mùi. Trên mỗi bồn cầu

đều có lọ hoa mẫu đơn nhỏ lịch lãm. Mẫu đơn còn gọi là bông trang, loại

hoa dễ trồng, có nhiều ở Lào và các nước Asean. Giật mình vì ý tưởng

sáng tạo bất ngờ mà ít tốn kém của chủ nhân.

Mới hay chưa giàu vẫn có thể sạch. Cha ông mình từng dạy “Đói cho sạch,

rách cho thơm”. Cái chính là nhận thức, là văn hóa. Tôi càng hiểu vì

sao là đất nước nghèo nhưng mỗi khi ra khỏi nước người Lào đều ăn mặc

tươm tất, sạch sẽ để “thiên hạ khỏi cười chê”.

Ở nước ta, những chuyện nhỏ như nhà vệ sinh mà mấy chục năm chưa dứt

điểm được thì nói chi chuyện lớn. Lại còn chuyện “tự sướng” với số liệu

điều tra mức độ hài lòng của khách quốc tế vừa được Tổng cục Du lịch

công bố: 94,09% tốt và cực tốt, chỉ 0,22% kém. Đẹp hơn cả mơ!

Cứ tô hồng kiểu đó thì vị trí “đứng đầu tốp cuối Asean” cũng đang bị

lung lay chứ đừng nói tăng tốc. Xét theo hiệu quả, du lịch Việt Nam kém

xa Lào và Campuchia. Dân số Lào 7 triệu người, đón 3,5 triệu khách quốc

tế năm 2014. Campuchia dân số 15 triệu người, đón 4,5 triệu khách. Còn

Việt Nam hơn 91 triệu dân chỉ đón được 7,9 triệu khách.

Du lịch Việt Nam muốn phát triển tốt xin hãy làm cuộc cách mạng, bắt

đầu từ việc nhỏ mà nhà vệ sinh phải là một trong những ưu tiên số 1.

Mong lắm thay!

27/5/2015

NGUYỄN VĂN MỸ (Lửa Việt Tours)

Linh Tinh

Gánh nặng nếu

biết cưu mang sẽ trở thành ánh sáng.

The burden

which is well borne becomes light.

Ovid

Nguồn

Note:

GCC

nghi câu này dịch trật. Câu tiếng Anh không có cụm từ “nếu biết”, vì

nếu dùng,

nó biến thành “điều kiện cách”, [“which is” mà làm sao lại biến thành

“nếu biết”]Câu này, như

1 vị thân hữu dịch giùm, qua mail:

"Gánh nặng

mà mang cho khéo, thì sẽ trở nên NHẸ"

Dù thế nào

chăng nữa, thì cũng không thể trở thành “ánh sáng” được! (1)

(1)

Nguoc goc

cua no o day

Today at

12:36 PM

Câu này của

OVID, người LA Mã, chết trước Chúa Giêsu khoảng chục năm

Bác tìm câu

Mathêu, chương 11, "hãy mang lấy ách của Ta' tìm trong usccb.org của

các

giám mục Mỹ, bác sẽ thấy light nghĩa là nhẹ nhàng.

Hãy đến với

Ta, hết thảy những kẻ lao đao và vác nặng". Và Ta sẽ cho nghỉ ngơi lại

sức:

29 Hãy mang lấy ách của Ta

vào mình, hãy thụ giáo với Ta, vì Ta hiền lành và

khiêm nhượng trong lòng, và các ngươi sẽ tìm thấy sự nghỉ ngơi cho tâm

hồn. 30

Vì chưng ách Ta thì êm ái, và gánh Ta lại nhẹ nhàng".

Bible Mathew

chpter 11

27 “All

things have been committed to me by my Father. No one knows the Son

except the

Father, and no one knows the Father except the Son and those to whom

the Son

chooses to reveal him.

28 “Come to

me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest. 29

Take my

yoke upon you and learn from me, for I am gentle and humble in heart,

and you

will find rest for your souls. 30 For my yoke is easy and my burden is

light.”

28 « Venez à

moi, vous tous qui peinez sous le poids du fardeau, et moi, je vous

procurerai

le repos.

29 Prenez

sur vous mon joug, devenez mes disciples, car je suis doux et humble de

cœur,

et vous trouverez le repos pour votre âme.

30 Oui, mon

joug est facile à porter, et mon fardeau, léger. »

*

Tks. NQT

Tôi nhớ trước

ngày 30 tháng 4 năm 75, ngồi bên radio nghe Tổng thống Nguyễn Văn Thiệu

đọc diễn

văn, tôi đánh bạo nói với cha tôi rằng (thì là) theo nhận xét của một

học sinh

như tôi thì diễn văn của tổng thống có vẻ không đúng với văn phạm tiếng

Việt mà

tôi được học chút nào. Cha tôi nhìn tôi im lặng một lát rồi buồn rầu

bảo, đại

ý, các chính thể đến giờ phút lụi tàn bao giờ cũng có những biểu hiện

như thế. (1)

Sự kiện là,

khi bộ tư lệnh của Hitler nói với ông ta, "Thưa Lãnh Tụ, chúng ta rất

đỗi

là cần, những chuyến xe lửa chở xăng dầu, vũ khí, chỉ xin Quốc Trưởng

[dành]

cho chúng tôi 4 tuần lễ ngưng chở người tới trại tử thần," ông ta trả

lời,

chiến thắng cuộc chiến chưa quan trọng bằng việc tận diệt bọn Do Thái.

Quan niệm

rằng ông ta khùng chẳng thuận tai tôi một chút nào, ở đây. Ông ta rất

không

khùng. Tôi cũng chẳng thấy thuận tai chút nào, khi biết rằng Stalin đã

huỷ diệt

một phần lớn đám dân có học của ông ta, một cách hệ thống, trong khi

lên kế hoạch

tạo thành sự vĩ đại của Liên Bang Xô Viết.

Steiner trả

lời The Paris Review (a)

Quan niệm rằng

ông ta khùng chẳng thuận tai tôi chút nào.

Nếu như thế,

thì không thể coi tên thi sĩ hải ngoại- khi cả Miền Nam sắp mất, trên

TV Sài

Gòn, Thiệu vừa khóc vừa xin lỗi người dân Miền Nam, vì quá tin vào lời

hứa

lèo của

Nixon, không bao giờ bỏ chạy, để Miền Nam lọt vào tay CS - và tên này

còn đủ

bình tĩnh để tìm ra mấy cái lỗi về văn phạm trong bài nói chuyện của

Thiệu -

là… khùng được!

Có 1 cái gì đó, đéo làm

sao hiểu được ở đây!

NQT

11.8.2007

Nguyễn Đức Tùng

1. Bài của Likhachev, “Phẩm tính

trí thức”, là bài rất có

ích cho các nhà văn. Tôi đặc biệt chú ý đến đoạn nói về cách sống và

phong độ

của giới trí thức Nga, cũng như đoạn về nhà văn Solzhenitsyn. Không

trách gì

nhiều nhà văn nước ta (chứ không phải là nhà văn “ở ta”) trước đây mê

văn học

Nga đến thế. Mà mê là đúng, vì họ lớn quá. Sang trọng. Tôi thiết nghĩ

các nhà

văn gốc miền Nam

và ở hải ngoại nên tìm đọc thêm về văn học và lý luận văn học Nga. Biết

bao

nhiêu điều để học, sao cứ đọc hoài Frost với lại Faulkner? Tuy nhiên

theo thiển

nghĩ của tôi, sự phân chia hướng Âu hay Á-Âu thật ra không quan trọng

lắm.

2. Nhận xét của nhà văn Nguyên Ngọc về tuyên bố của Bộ

trưởng Thông tin-Truyền thông rất chính xác, thẳng thắn, mà vẫn có ý vị

văn

chương. Tôi rất thích đoạn ông bắt bẻ về vụ mười chữ và năm từ. Thật ra

từ vẫn

gọi là chữ được, vì từ hay chữ chỉ là qui ước của các nhà ngữ pháp sau

này

thôi, chứ lúc tôi còn đi học không có sự phân biệt đó. Vấn đề chính là,

đúng

như Nguyên Ngọc nói, nói năm từ hay chữ (đôi) thì đúng hơn là nói mười

chữ.

Mười chữ đơn lẻ không có nghĩa gì cả. Tôi nhớ trước ngày 30 tháng 4 năm

75,

ngồi bên radio nghe

Tổng thống Nguyễn Văn Thiệu đọc diễn văn, tôi đánh bạo nói với cha tôi

rằng

(thì là) theo nhận xét của một học sinh như tôi thì diễn văn của tổng

thống có

vẻ không đúng với văn phạm tiếng Việt mà tôi được học chút nào. Cha tôi

nhìn

tôi im lặng một lát rồi buồn rầu bảo, đại ý, các chính thể đến giờ phút

lụi tàn

bao giờ cũng có những biểu hiện như thế.

3. Nhờ cái link của talawas mà tôi cũng đọc được bài “ Hồ

Anh Thái có sợ giải thiêng?” trên VietNamNet nói về tác phẩm Đức Phật,

nàng

Savitri và tôi. Cuốn này có trích đăng trên talawas chủ nhật,

tôi chưa

kịp đọc,

nhưng Hồ Anh Thái thì tôi có đọc qua một hai cuốn khác vì bạn bè

khuyên. Tôi

cũng chưa đọc Phạm Xuân Thạch bao giờ, không biết ông có ký tên nào

khác không,

hay chỉ vì tôi ít đọc các nhà văn trong nước. Bài của ông làm tôi ngạc

nhiên

quá: tôi lấy làm mừng cho nền phê bình văn học Việt Nam.

Ít ra cũng phải có những bài

review mạnh mẽ, thuyết phục, khen chê rõ ràng như vậy. Thường thì các

nhà phê

bình Việt Nam

chỉ khen các nhà văn nhà thơ chứ không chỉ ra được cho họ các khuyết

điểm nghệ

thuật cần tránh.

Xin cám ơn La Thành, Nguyên Ngọc, Phạm Xuân Thạch, và Ban

biên tập talawas.

Nguồn

Bạn, đọc 1

cái "viết" của tên này, trên talawas, thì phải hình dung ra, đây là 1

đấng cực kỳ

"bố chó xồm" của hải ngoại, ông tiên chỉ VP cũng không có được thứ văn

phong hách

xì xằng như trên!

Thực tế, có ai biết hắn là thằng nào đâu.

Vậy mà, 40

năm thơ ca ở hải ngoại.

Cũng được đi,

nhưng đọc, như kít, cái đó mới khốn nạn.

Trích dẫn,

toàn những tên quen biết của hắn, cũng là 1 cách kéo bè kéo đảng.

Tếu nhất,

là, khi bị độc giả talawas nhẹ nhàng nhắc nhở, hắn sorry, "Tôi quên mất

tâm lý dễ bị tổn thương ở một vài người." [Nguồn

talawas].

Vẫn cái

giọng

thổi đít VC!

Linh Tinh

Câu hỏi trong đầu tôi sau khi trở về, “Làm thế nào để một đất nước có

nhiều người đi xem tác phẩm nghệ thuật như thế này?” Getty Center, sáng

lập bởi gia sản dầu hỏa của J. Paul Getty, một nhà doanh nghiệp Hoa kỳ

(s. 1892-c. 1976), về khuynh hướng nghệ thuật không hiện đại và đương

đại bằng các viện bảo tàng ở New York hay Washington DC., hoặc MOCA

(Museum of Modern Art – Los Angeles). (1)

Tay này không biết viết tiếng Mít: Getty Center, sáng lập bởi gia sản

dầu hỏa của J. Paul Getty.

Mít viết, sáng lập "nhờ" gia sản.

Một câu tiếng Việt viết không nên thân.

Viết như thế, thì vẽ chắc cũng rứa!

Trần Doãn Nho viết:

Một bài biên khảo đượm chất…tùy bút. Đọc rất thích! Và cảm thấy yêu thơ

hơn.

Cám ơn Nguyễn Đức Tùng. (2)

GGC muốn hỏi, thi pháp "chấn thương", nó ra làm sao?

Thi pháp, nôm na là cách, ở đây, cách làm thơ. Cách làm thơ mà…

chấn thương?

Một tên điên viết loạn cào cào mà cũng có người khen.

Lời khen cũng quái. Biên khảo mà viết như tuỳ bút? Cảm thấy yêu thơ

hơn, là do… sao?

Do biên khảo viết như tùy bút?

GCC đã nói rồi, cả một lũ không rành tiếng Mít!

V/v viết cái này mà lại ra cái kia, có, nhưng ở vài bậc thầy, thí dụ

Borges, như đoạn sau đây cho thấy:

… Poetry, short story, and essay are all complementary in Borges' work,

and often it is difficult to tell into which genre a particular text of

his fits. Some of his poems tell stories, and many of his short stories

- the very brief ones especially - have the compactness and delicate

structure of prose poems. But it is mostly in the essay and short story

that elements are switched, so that the distinction between the two is

blurred and they fuse into a single entity. Something similar happens

in Nabokov's novel Pale Fire, a work of fiction that has all the

appearance of a critical edition of a poem. The critics hailed the book

as a great achievement. And of course it is. But the truth is that

Borges had been up to the same sort of tricks for years - and with

equal skill. Some of his more elaborate stories, like 'The Approach to

al-Mu'tasim', 'Pierre Menard, the Author of Don Quixote', and 'An

Investigation of the Works of Herbert Quain', pretend to be book

reviews or critical articles.

Vargas Llosa: The Fictions of Borges

[Trong “In Memory of Borges”. TV sẽ giới thiệu toàn bài viết]

Dịch thoáng: Thơ, truyện ngắn, và tiểu luận tất cả bổ túc cho nhau

trong tác phẩm của Borges, và thường thật khó chỉ ra môn võ nào ông

bảnh nhất. Vài bài thơ kể chuyện kể, và rất nhiều truyện ngắn có cấu

trúc của thơ xuôi. Nhưng hầu như trong tiểu luận và truyện ngắn, những

thành phần trộn vào nhau và biên giới giữa chúng mờ đi, để có 1 thực

thể độc nhất. Trường hợp tương tự như vậy đã xẩy ra với tiểu thuyết

“Nhạt Lửa” của Nabokov, một giả tưởng có bề ngoài của 1 bản văn phê

bình một bài thơ.

Với hai đấng Mít, GCC sợ rằng, chỉ là áo thụng vái nhau, chẳng tên nào

hiểu, chúng nói/viết cái gì nữa!

Một tên thì hải ngoại chê, bèn về trong nước bợ đít VC, in ấn loạn cào

cào, có ai thèm đọc, mà đọc làm sao nổi. Khùng điên ba trợn làm sao

đọc! Nghe Thiệu đọc diễn văn Miền Nam sắp đi đoong, mà nhận ra mấy lỗi

sai văn phạm! (1)

Còn 1 đấng thì cũng viết từ thuở tóc còn xanh, nhưng thú thực, GCC

không đọc được, do quá thiếu chất văn học, và chỉ có mỗi 1 lần, viết

được, là lần kể cuộc sống lầm than sau 1975, và chính là khi TDN từ bỏ

giấc mộng văn chương, hay, quên hẳn nó, và viết, thì lại rất được.

GCC phải viết rõ ra, để chứng tỏ, GCC có đọc, và đọc rất kỹ những nhà

văn trước 1975 của Miền Nam!

Lần GCC đọc tác phẩm đầu tay của THT mà chẳng thú sao.

Biết trước, báo động liền, coi chừng thua cuộc chiến... thứ nhì,

vậy mà vẫn không thoát!

NQT

(1)

Tôi nhớ trước ngày 30 tháng 4 năm 75, ngồi bên radio nghe Tổng thống

Nguyễn Văn Thiệu đọc diễn văn, tôi đánh bạo nói với cha tôi rằng (thì

là) theo nhận xét của một học sinh như tôi thì diễn văn của tổng thống

có vẻ không đúng với văn phạm tiếng Việt mà tôi được học chút nào. Cha

tôi nhìn tôi im lặng một lát rồi buồn rầu bảo, đại ý, các chính thể đến

giờ phút lụi tàn bao giờ cũng có những biểu hiện như thế.

Một tên viết như thế, liệu có thể viết văn, làm thơ, viết tiểu luận

như... tùy bút?

GCC thực sự nghĩ, tên này bất bình thường, hoặc quá tí nữa, khùng!

Nhân nhắc tới TDN:

Vấn đề “tương tự” trong ẩn dụ

THT

Liệu có gì là “tương tự”, không, khi, Dũng nhìn sang nhà kế bên, thấy 1

cái áo cánh trắng, phất phơ bay trong gió, trong nắng, và ngạc nhiên tự

hỏi, áo của ai nhỉ, và bèn nhớ ra, hè rồi, Loan đi học trên tỉnh, về

rồi.

Với 1 độc giả lười biếng, họ chỉ đọc đến có vậy.

Với 1 độc giả biết 1 tí về “tương tự”, biết tưởng tượng, cái này giống

cái kia đúng hơn, thì đoạn trên có nghĩa tương tự: “anh yêu em”.

Dũng, đúng lúc đó, khám phá ra, tình yêu của mình.

Bài viết, trên Blog của 1 người quen

của GCC, nếu bạn không có “sáng tạo” trong khi đọc, thì thấy cũng

thường thôi, nhưng với Gấu Cà Chớn, ẩn giấu trong đó, vài "vấn nạn lớn"

của... viết!

Ít nhất thì cũng chứa đựng, trong nó, đề tài "sống cuộc đời này, mơ

cuộc đời khác", mà Kafka đã từng chỉ ra, trong truyện ngắn “Trước Pháp

Luật”, “Devant La Loi”, và 1 đề tài nữa, cũng từ Kafka, “Làng Kế Bên.”

Một cách nào đó, bà vợ trong “Vài hàng gọi là có viết” đã đến được

“Làng Kế Bên”, “Cuộc Đời Khác”, trong mấy ngày ông chồng xa nhà!

Khen Bà này, cũng kẹt lắm, vì Bà thực sự không muốn được khen, sợ hư

mất cõi văn chưa thành của Bả!

Làng kế bên.

Nội tôi thường nói: "Đời vắn chi đâu. Như nội đây, nhìn lại nó, thấy

đời như co rút lại, thành thử nội không hiểu nổi, thí dụ như chuyện

này: bỏ qua chuyện tai nạn, làm sao một người trẻ tuổi có thể quyết tâm

rong ruổi sang làng kế bên, mà không e ngại, một đời thọ như thế, hạnh

phúc như thế, cũng không đủ thời gian cần thiết cho một chuyến đi như

vậy."

Bản tiếng Anh: The next village.

My grandfather used to say: "Life is astoundingly short. To me, looking

back over it, life seems so foreshorthened that I scarcely understand,

for instance, how a young man can decide to ride over to the next

village without being afraid that – not to mention accidents – even the

span of a normal happy life may fall far short of time needed for such

a journey".

Ba Trăm Năm Sau Có Ai Khóc Gấu Cà Chớn?

Camus có truyện ngắn "Người đàn bà ngoại tình", câu chuyện về một người

đàn bà, đêm đêm, sau khi làm xong hết bổn phận của người vợ, trong cuộc

lữ của cả hai vợ chồng, đã len lén thoát ra ngoài, để ngắm trời ngắm

sao...

Đây là một đề tài lớn của dòng văn chương hiện sinh, theo tôi, thoát

thai từ truyện ngắn "Before the Law", của Kafka.

Đây là câu chuyện một người nhà quê ra tỉnh, tới trước "Pháp Luật",

tính vô coi cho biết, nhưng bị người lính gác cản lại. "Anh vô được mà,

nhưng đợi chút xíu nữa đi". Chờ hoài chở hủy, chút xíu nữa đi hoá ra là

cả một cuộc đời. Trước khi chết, anh nhà quê phều phào hỏi, tại sao chỉ

có một mình anh tính vô chơi, coi cho biết; người lính gác nói: cửa này

chỉ mở ra cho anh, tôi đứng đây, cũng chỉ vì anh; nhưng bây giờ anh đâu

cần tới nữa, và tôi cũng xong bổn phận ở đây. Nói xong anh bỏ đi.

Trong truyện ngắn Eveline của James Joyce, trong tập "Những người dân

thành phố Dublin", người lính của Kafka xuất hiện qua anh chàng thuỷ

thủ tầu viễn dương. Một người yêu thương, và có đủ điều kiện để đưa cô

gái Evelyne tới một cuộc sống khác tốt đẹp hơn; nhưng tới giờ phút

chót, cô gái quyết định "ở lại".

NQT đọc Biển của Miêng

Có thể nói, mẩu viết còn vượt lên khỏi cái cõi “thần tiên” của cả hai

truyện ngắn của Kafka, vì cái cõi khác kia, cuộc đời khác kia, lại

chính là cuộc đời này: Nhờ ông chồng đi vắng, bà vợ tự cho phép mình

được cho độc giả biết thêm 1 tí về bà: thèm ngủ thêm 1 tí, lười thêm 1

tị, ăn thêm 1 miếng, thay vì diet như con mèo của mình…..

Tuyệt, quá tuyệt.

Câu cuối mới thần sầu:

Đến thứ Hai chàng mới về, tôi dè xẻn thời giờ còn lại mà tôi có thể

lười biếng.

Từ"dè xẻn" mới đắt làm sao!

Gấu đã định giấu những dòng trên, dành riêng cho mình, vì sợ bị chửi,

đừng khen tui nhiều quá!

Congrat!

Hà, hà!

Bà Tám says:

April 15, 2013 at 6:11 am

Tám thấy độc giả từ tanvien.net vào blog biết là Bác đã giới thiệu cái

gì đó. Tại vì mỗi lần bác chê hay khen đều có rất nhiều người muốn biết

cái mà Bác để ý. Đúng là cái sức mạnh của ngòi bút có tiếng. Bác nổi

tiếng là dám nói thẳng và nói thật, nên Tám xin cảm tạ lời khen của

Bác. Tám nghĩ chắc Bác đã từng biết qua, hay thèm muốn có được, một sự

tuyệt đối solitude để suy nghĩ, để viết. Cái cảm giác thanh thản, không

bị ngó chừng, không bị bắt buộc phải theo khuôn khổ, cái tự do tuyệt

đối người viết nào cũng thèm muốn. Được bác khen là một hân hạnh rất

lớn. Xin cám ơn Bác.

You're welcome

NQT

Secret Histories

By Deborah Treisman

When we began putting together this

summer’s Fiction Issue, we planned to focus on stories set at

particular

moments in history. At a certain point, we realized that all the pieces

we’d

chosen also involved secrets: Jonathan Franzen’s novel excerpt, “The Republic

of Bad Taste,” deals with a murder

in East Berlin in the nineteen-eighties; the two heroines of Karen

Russell’s

story, “The Prospectors,”

are Depression-era grifters who

attend a party thrown by ghosts; Primo Levi’s narrator hides a centaur

in his

barn, in “Quaestio de

Centauris”; and, in “Escape from

New York,” Zadie Smith tells the

(reportedly partly true) story of Michael Jackson, Marlon Brando, and

Elizabeth

Taylor fleeing New York City in a rental car on September 11, 2001. In

the end,

we titled the issue “Secret Histories.” And perhaps that

is,

ultimately, the job of all fiction: to tell us the stories that the

news and

the historical accounts don’t tell us, to uncover the secrets of the

past (and

the present, and even the future).

The archival stories included in this collection

are also set in the past and also

involve the hidden lives behind historical events. Two of the stories

take

place during the Second World War: in Alice Munro’s “Amundsen,”

a schoolteacher has a secret wartime

love affair while working at a tuberculosis sanatorium, and Cynthia

Ozick’s

iconic story “The Shawl”

takes us into the horror of a Nazi

concentration camp. ZZ Packer’s “Dayward”

carries us farther back, to the

Reconstruction-era South, and the odyssey of two children running

away

from the woman who enslaved them. Dinaw Mengestu’s “The Paper

Revolution” is set in the

nineteen-seventies, during a period of student uprising at an

unnamed

African university. In Salman Rushdie’s “In the South,”

two old men indulge their lifelong

rivalry, in the coastal town of Chennai, India, moments before the 2004

tsunami

hits. Finally, in “Old Wounds,”

Edna O’Brien’s narrator travels to

Ireland to revisit her past, only to discover that some secrets will

always be

secrets, that even one’s own history can be ultimately unknowable. At

the

family graveyard, she asks herself, “Why . . . did I want to be buried

there?

Why, given the different and gnawing perplexities? It was not love and

it was

not hate but something for which there is no name, because to name it

would be

to deprive it of its truth.”

ABOUT

Each day we'll show you all

of your stories from the same date on different years.

CON ĐƯỜNG DÀI VÀ ĐẪM MÁU NHẤT

Chế độ cộng sản tại Việt Nam hiện nay là một chế độ

phong kiến nhưng không

có áo mão. Vậy thôi. Nếu ở Tây phương, sau khi chủ nghĩa cộng sản cáo

chung ở

Đông Âu, người ta nhận định: “Chủ nghĩa cộng sản là con đường dài nhất

và đẫm

máu nhất từ chủ nghĩa tư bản đến chủ nghĩa tư bản” thì ở Việt Nam, nơi

người

ta, nhân danh cách mạng, kết liễu một triều đại có thật nhiều lăng để

xây dựng

một triều đại mới trên nền tảng một cái lăng thật đồ sộ và thật...

Note: Do không đọc được bản gốc, mà cũng đâu dám

trích dẫn nguồn, từ trang

TV, mới ra thứ quái thai mà Thầy Kuốc tự hào là những cú đấm chan chát

như thế

này!

“Chan chát”?

Không, chắc là “chôm chôm”!

Đúng là “bạn quí” của “ông số 2”.

Cũng cùng 1 phường!

NQT

Nhức nhối [đẫm máu] thực, con đường đi từ tờ Văn

Học tới Facebook!

Câu nói của Todorov, là mô tả 1 "hiện trạng" lịch

sử, ở những nước ngày nào CS bây giờ tư bản, “tư bản đỏ” như thường

gọi. Câu mô phỏng thật tức cười, chưa kể cái sự thiếu lương thiện về

trí thức, ăn cắp mà lại không dám chỉ rõ nguồn, cứ nhập nhà nhập nhằng.

“Ông số 2” chôm thơ ông số 1, là theo kiểu này, “của 1 thi sĩ”, thi sĩ

nào, đếch nói tên, cố tình làm độc giả hiểu lầm, “của tớ đấy”, vì ông

số 2 cũng là… thi sĩ!

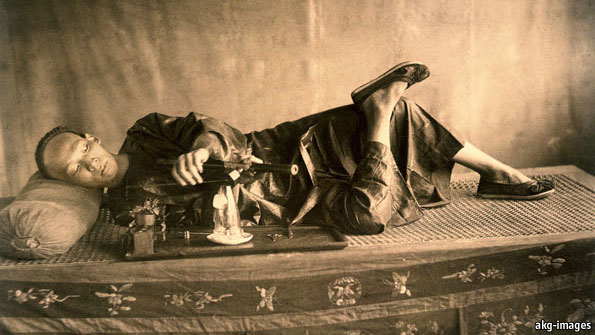

The Opium Wars

A time when the West clamoured for free

trade with China

Dude,

where’s my rickshaw? Dude,

where’s my rickshaw?

The Opium War: Drugs, Dreams, and the Making of

China. By Julia Lovell. Picador; 480 pages; £25. Buy

from Amazon.co.uk

HISTORY, it turns out, is not just written by the

winners. In documenting the historical crapshoot of the last 200 years,

there have been few losers more assiduous than the Chinese. So, apart

from adapting first Karl Marx and now Adam Smith, what have they been

writing? Rather a lot, it seems. A topic of choice is the Opium Wars,

those 19th-century skirmishes on the far-eastern fringe of the British

empire. They are largely unknown by British schoolchildren, but

successive Chinese governments have made sure the same cannot be said

for their overachieving students in the Middle Kingdom.

Julia Lovell's excellent new book explores why this

period of history is so emotionally important for the Chinese. Drawing

on original sources in Chinese and English, she recounts the events of

the period in fascinating detail. More importantly, she explains how

China has turned the Opium Wars into a founding myth of its struggle

for modernity.

Ms Lovell weaves this story into the historical brocade

of the early 19th century, when European demand for Chinese silk, tea

and porcelain was insatiable. To save their silver, the British began

to pay for these luxuries with opium from India, and many Chinese were

soon addicted. The Chinese emperor tried to stop the trade, and hoped

to slam the door completely on the outside world. Between 1839 and

1842, the British manufactured a nasty little war in which they smashed

the Chinese military, and justified it all in the name of free trade.

The Western powers, hungry for more markets, then prised China open.

Westerners have good reason to be ashamed of their

treatment of China in the 19th century. Yet Ms Lovell contends that

they administered only the final blows to an empire that was already on

the brink. That is hardly how it has been portrayed in China, however,

where manipulating memory is an important tool of government

propaganda. In the 1920s Chinese nationalists began spinning the

arrival of Western gunboats as the cause of all the country's

problems—the start of China's “century of humiliation”. Chairman Mao

also blamed Western aggression at the time of the Opium Wars for

China's decline. And so emerged the narrative of China as victim that

can still be heard today, even as the country casts off its loser

status.

Despite China's growing strength, Ms Lovell sees

worrying similarities between China's weaknesses today and those of the

Chinese empire of 1838, describing both as “an impressive but

improbable high-wire act, unified by ambition, bluff, pomp and

pragmatism”. She finds parallels too in how the West sees China.

Foreign policy hawks in 1840 repeated loudly that violence against

China “was honourable and inevitable until, in the popular imagination,

it became so.” Demonisation of China today, especially in America, can

sometimes seem almost as shrill.

Westerners interested in why China behaves the way it

does should read “The Opium War”. So should Chinese readers, who could

gain a more balanced view of their own history than they receive in

school. In 2006, for example, China's government shut down a leading

liberal weekly over an article that challenged national orthodoxy on

the Opium Wars. The Communist Party's propaganda bureau accused the

author of attempting “to vindicate criminal acts by the imperialist

powers in invading China”. An internet post by a nationalist suggested

the author should be “drowned in rotten eggs and spit”.

Ms Lovell reassures her readers that not all Chinese buy

into tired government propaganda. But the Opium Wars are always there,

lurking in the Chinese subconscious, perpetuating the tension between

pride and victimhood. Tellingly, Ms Lovell quotes George Orwell: “Who

controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present

controls the past.”

|

|

Dude,

where’s my rickshaw?

Dude,

where’s my rickshaw?