|

Bi Khúc 4

Tháng Sáu

Foreword

As a firm

believer in nonviolence, freedom, and democratic values, I have

supported the

nonviolent democracy movement in China from its beginning. One of the

most

encouraging and moving events in recent Chinese history was the

democracy movement

of 1989, when Chinese brothers and sisters demonstrated openly and

peacefully their

yearning for freedom, democracy, and human dignity. They embraced

nonviolence

in a most impressive way, clearly reflecting the values their movement

sought

to assert.

The Chinese

leadership's response to the peaceful demonstrations of 1989 was both

inappropriate and unfortunate. Brute force, no matter how powerful, can

never

subdue the basic human desire for freedom, whether it is expressed by

Chinese

democrats and farmers or the people of Tibet.

In 2008, I

was personally moved as well as encouraged when hundreds of Chinese

intellectuals and concerned citizens inspired by Liu Xiaobo signed

Charter 08,

calling for democracy and freedom in China. I expressed my admiration

for their

courage and their goals in a public statement, two days after it was

released.

The international community also recognized Liu Xiaobo's valuable

contribution

in urging China to take steps toward political, legal, and

constitutional

reforms by supporting the award of the Nobel Peace Prize to him in 2010.

It is ironic

that today, while the Chinese government is very concerned to be seen

as a

leading world power, many Chinese people from all walks of life

continue to be

deprived of their basic rights. In this collection of poems entitled

June

Fourth Elegies, Liu Xiaobo pays a moving tribute to the sacrifices made

during

the events in Tiananmen Square in 1989. Considering the writer himself

remains

imprisoned, this book serves as a powerful reminder of his courage and

determination and his great-hearted concern for the welfare of his

fellow

countrymen and women.

HIS HOLINESS

THE FOURTEENTH DALAI LAMA, TENZIN GYATSO

September 3,

2011

Là một người

vững tin vào bất bạo động, tự do và những giá trị dân chủ, tôi hỗ trợ

phong trào

dân chủ bất bạo động ở TQ kể từ lúc khởi đầu của nó. Một trong những sự

kiện phấn

khởi, cảm động nhất trong lịch sử gần đây của TQ là cuộc vận động 1989,

khi anh

chị em TQ diễn hành công khai và ôn hòa đòi hỏi tự do, dân chủ và phẩm

giá con

người. Họ ôm lấy bất bạo động trong một

cung cách ấn tượng nhất, phản ảnh rõ ràng những giá trị mà phong trào

mong tìm đạt

được.

Nhà cầm quyền

TQ, và cách đối xử của họ đối với những cuộc biểu tình 1989 thì vừa

không thích

hợp, vừa đáng tiếc. Sức mạnh cục súc, dù mãnh liệt cỡ nào, thì cũng

không bao

giờ làm khuất phục ao ước cơ bản của con người cho tự do, hoặc được

diễn tả bởi

những nhà dân chủ và những chủ đất, chủ trại người

TQ, hay người dân Tây Tạng.

Vào năm

2008, cá nhân tôi cảm thấy vừa cảm động, vừa hứng khởi khi hàng trăm

trí thức và

công dân TQ quan tâm, được tạo hứng bởi Liu Xiaobo, đã ký tên nơi Hiến

Chương

08, kêu gọi dân chủ và tự do cho TQ. Tôi biểu lộ lòng kính mến và ái mộ

của mình

trước sự can đảm và những mục tiêu đòi hỏi của họ, trong phát biểu công

khai trước

công chúng, hai ngày sau khi Hiến Chương được công bố. Cộng đồng thế

giới còn thừa

nhận đóng

góp quí giá của Liu Xiaobo trong việc đòi hỏi TQ tạo những bước tiến

trong việc cải cách chính trị, luật pháp,

và định

chế, bằng cách hỗ trợ, và mừng rỡ, khi ông được trao giải thưởng Nobel

Hòa Bình

vào năm 2010.

Một điều trớ

trêu, là, vào ngày này, trong khi chính quyền TQ rất quan tâm tới việc

làm thế nào để TQ

được coi như là một cường quốc trên thế giới, thì chính cường quốc mong

được cả

thế giới công nhận đó, lại đối xử cực kỳ tàn nhẫn với dân chúng của họ,

bằng cách

tước đoạt hết của họ những quyền cơ bản của con người. Trong tập thơ Bi Khúc Tháng

Sáu Ngày Bốn, Liu Xiaobo tưởng niệm, vinh danh những hy sinh,

mất

mát xẩy ra

trong những biến động ở Công Trường Thiên An Môn 1989. Trong khi nhà

văn, nhà

thơ, vào chính lúc này, vẫn còn đang ngồi tù, thì tập thơ quả đúng là

một nhắc

nhở mãnh liệt về sự can đảm, quyết tâm, và sự quan tâm bằng trái tim

lớn nóng hổi

của ông, dành cho xứ sở và đồng bào của mình.

DALAI LAMA

4

Refused to

eat

Stopped

masturbating

Picked up a

book from the ruins

Marvel at a

corpse's humility

Within a

mosquito's internal organs

a dark-red

dream

approaches a

spy-hole in the iron door

Converse

with a vampire

No need to

be so covert so cautious anymore

A sudden

stomach spasm

gives me the

courage before death

to spew out

a curse:

Fifty years

of glory

there's only

the Communist Party

and no sign

of the New China-y

Standing in

the Curse of Time

Before dawn at the re-education through

labor camp

in Dalian, 6/4/1999

Tenth anniversary offering for 6/4

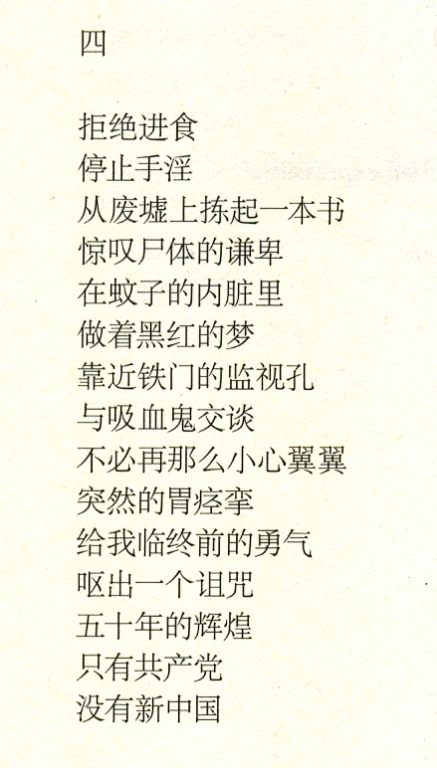

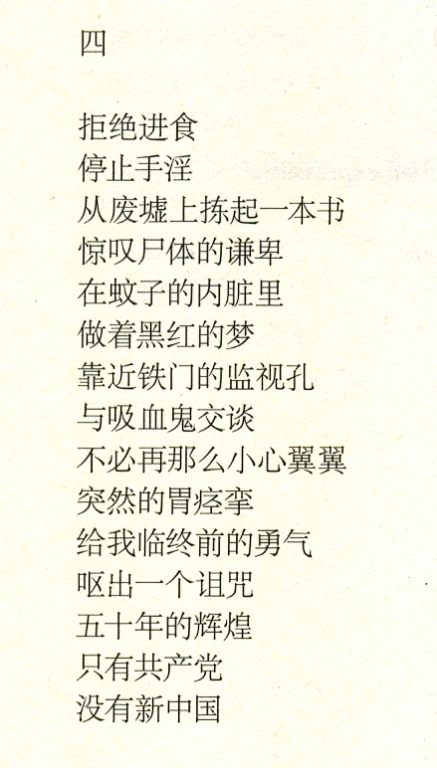

IV

Tuyệt thực

Ngưng thủ

dâm

Nhặt một cuốn

sách từ trên đống đổ nát

Cảm thán sự

khiêm nhường của thi thể

Mơ một giấc

mộng đen đỏ

Ngay bên

trong bụng muỗi

Lại gần lỗ

giám sát (*) trên cánh cửa sắt

Đối thoại với

quỷ hút máu

Giờ đâu cần

phải cẩn trọng tỉ mỉ đến thế

Cơn co thắt

dạ dày đột ngột

Ngay trước

phút lâm chung, mang đến cho tôi dũng khí

Nôn ra một lời

nguyền rủa:

Năm mươi năm

huy hoàng

Chỉ có Đảng

Cộng Sản

Không có nước

Trung Hoa mới

Dã Viên dịch

---------

Ghi chú:

(*) nguyên

văn chữ Hán: "Giám thị khổng" (một cái lỗ trên cửa nhà tù để theo dõi,

giám sát

tù nhân)

Note: Bản dịch

của 1 độc giả TV, từ tiếng Trung.

Tks. Many

Tks.

Take Care.

NQT

TV sẽ đi 1

tuyển tập thơ dịch, từ Bi Khúc 6/4,

trong những kỳ tới. Bản tiếng Việt

sẽ dịch

thẳng từ nguyên tác tiếng Trung, kèm cả hai bản tiếng Trung/tiếng Anh.

Xin kính mời

độc giả đón coi!

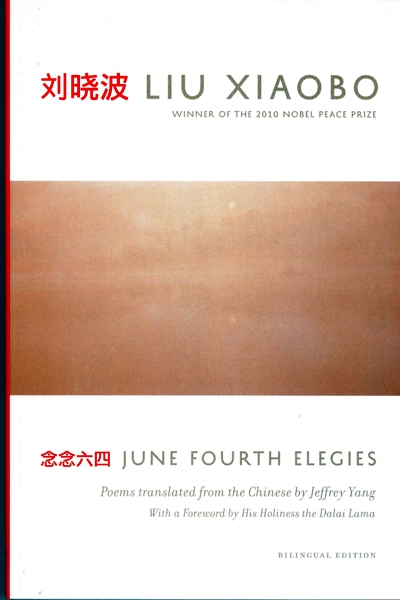

Liu Xiaobo

Bi Khúc Bốn

Tháng Sáu

Bi Khúc 2

Standing

in

the Curse of Time

Đứng trong

Nguyền Rủa của Thời Gian

Nguyên tác chữ Hán

IV

Tuyệt thực

Ngưng thủ

dâm

Nhặt một cuốn

sách từ trên đống đổ nát

Cảm thán sự

khiêm nhường của thi thể

Mơ một giấc

mộng đen đỏ

Ngay bên

trong bụng muỗi

Lại gần lỗ

giám sát (*) trên cánh cửa sắt

Đối thoại với

quỷ hút máu

Giờ đâu cần

phải cẩn trọng tỉ mỉ đến thế

Cơn co thắt

dạ dày đột ngột

Ngay trước

phút lâm chung, mang đến cho tôi dũng khí

Nôn ra một lời

nguyền rủa:

Năm mươi năm

huy hoàng

Chỉ có Đảng

Cộng Sản

Không có nước

Trung Hoa mới

Cái tít của

bi khúc, “Thời Nguyền Rủa”, cho thấy sự tương phản giữa hai

câu thơ

Câu

chuyện đông phương cổ xưa ấy

Bỗng muốn nhỏ xuống từng giọt tươi rói

Liu Xiaobo

Và

Giọt mưa trời

khóc ngàn năm trước

Sao còn ướt

trên lưng bàn tay

TMT

Brodsky phán:

Xuyên suốt

cuộc đời 1 người, Thời gian nói [address] với Con Người trong muôn vẻ,

variety,

ngôn ngữ; ngôn ngữ của sự ngây thơ, tình yêu, niềm tin, kinh nghiệm,

lịch sử, ...

Trong những ngôn ngữ đó, ngôn ngữ của tình yêu rõ ràng là một lingua franca, ngôn ngữ bắc cầu. Bộ từ điển

của nó, its vocabulary hấp thụ, nuốt, absorb, tất cả những tiếng nói

khác,

other tongues, và sự phát ra của nó, its utterance, thí dụ, anh

thương em, làm hài lòng, gratify, một

chủ thể, a subject, cho dù vô tri vô giác,

inanimate, cỡ nào. Bằng cách thốt ra như thế, anh thương em,

chủ thể sướng điên lên, và cái sự sướng điên lên đó,

nói lên, làm vọng lên, echoing, cả hai chiều: chúng ta cảm nhận những

đối tượng

của những đam mê của chúng ta, và cảm nhận Lời Chúa [Good Book’s

suggestion], và Chúa là gì, as to what God is.

Tình yêu thiết

yếu là một thái độ được gìn giữ,

maintain, bởi cái vô cùng đối với cái hữu hạn. Sự đảo ngược, the

reversal, tạo

nên, hoặc niềm tin, hay thi ca.

Đoạn trên,

theo GCC, là cơ bản thiết yếu, của thơ Brodsky.

Nói rõ hơn, thơ của ông là thơ

tôn giáo, thơ của một nhà thơ Ky Tô. Chính vì thế, GCC khó nhập vô thơ

ông, vì

là 1 tên ngoại đạo. GCC viết ra, để phúc đáp 1 vị độc giả, tại sao Gấu

lèm bèm

hoài về Brodsky mà không dịch thơ Brodsky!

Bi Khúc Bốn

Tháng Sáu

Bi Khúc 1

Trải

nghiệm cái chết

Bi Khúc 2

Đứng trong nguyền rủa của

thời gian

Cái ngày ấy vô cùng lạ lẫm

II

Mười năm

sau, chính hôm nay

Binh sĩ được

huấn luyện bài bản

Dùng tư thế

chuẩn nhất nghiêm trang nhất

Để bảo vệ sự

dối trá ngất trời

Cờ năm sao

chính là bình minh

Đón gió tung

bay trong ánh sớm

Mọi người

nhón cao gót, vươn dài cổ

Tò mò,

choáng ngợp và kính ngưỡng,

Một người mẹ

trẻ

Giơ cao cánh

tay nhỏ của đứa con trong lòng

Tỏ ý tôn

kính lời dối trá đang che cả bầu trời

Một người mẹ

khác, tóc bạc

Hôn lên tấm

di ảnh đứa con trai

Bà bày ra từng

ngón tay của đứa con

Tỉ mỉ rửa sạch

từng vết máu trên mỗi chiếc móng

Bà tìm không

ra một dúm đất

Để con trai

dưới đất được yên nghỉ

Bà chỉ có thể

treo con ở trên tường

Bà mẹ này đi

khắp những ngôi mộ vô danh

Để soi thấu

lời dối trá thế kỷ

Từ trong cổ

họng bị thít chặt

Nấc ra những

cái tên đã bị ngạt thở

Để tự do và

tôn nghiêm của chính mình

Thốt ra lời

tố cáo sự quên lãng

Bị cảnh sát

theo dõi và nghe lén

2

Ten years

later today's

well-trained

soldiers

a most

official most stately posturing

guard that

wholly monstrous lie

Red

five-starred flag in dawn's

morning

light flutters in the wind

People rise

up on their feet, stretch their necks high

so strange,

such stunned reverence

A young

mother holds her child

to her chest

and raises its little hand

to salute

the lie that blots out the sky

A different

mother hair grayed

kisses a

photograph of her dead son

She pries

open each of his fingers

to gently

wash the dried blood beneath his nails

She's unable

to find a handful of dirt

to give her

son peace beneath earth

She just

hangs her son up onto the wall

This mother

of a nameless grave who walks on

and on to

expose a world's lie

with throat

constricted forces out

the

suffocated names

to turn her

own freedom and dignity

into a

denouncement of forgetting

that tails and

wiretaps the police

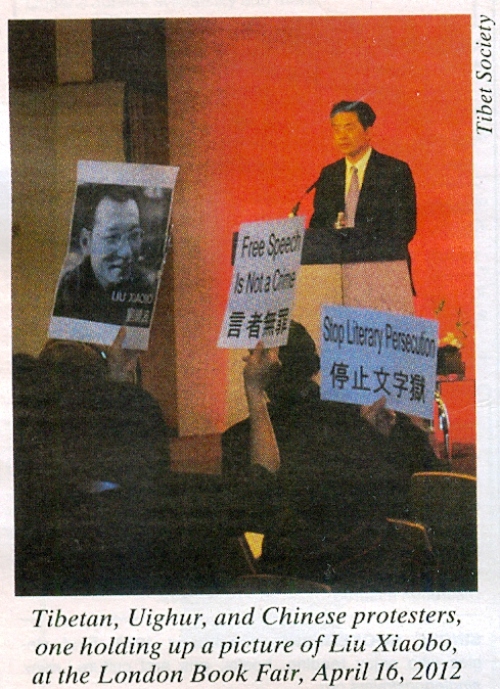

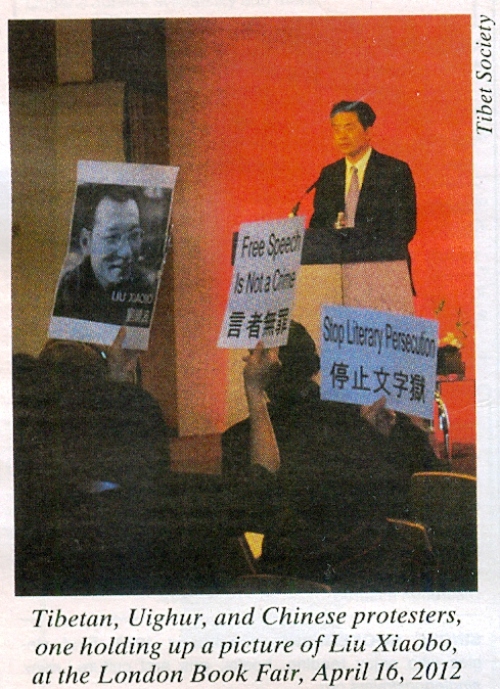

London: The Triumph of the

Chinese Censors

Chiến

Thắng Của Anh Tẫu Kiểm Duyệt Ở Luân Đôn

Jonathan

Mirsky

When I

arrived at the London Book Fair on Monday, April 16, I saw a huge sign

outside

showing a cute Chinese boy holding an open book with the words

underneath him:

"China: Market Focus." The

special guest of this year's fair was the

Chinese Communist Party's censorship bureau. Assisted by the

government-funded,

but independent, British Council, the fair's organizers invited the

General

Administration of Press and Publication (GAPP)-the Communist Party's

designated

body for ensuring that all publications, from poems to textbooks, are

certified

fit for the public at home and abroad to read. What has caused a bitter

public

wrangle in London is that Beijing not only chose-with the full approval

of the fair

itself and of the British Council- which writers to bring to the fair.

In a disturbing

repeat of what happened at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2009, it also

excluded

many of China's best-known writers. Among these are two Nobel Prize

winners:

Gao Xingjian, China's only Literature Prize laureate, who lives in

nearby

Paris, and Liu Xiaobo, the Peace Prize winner who is now serving an

eleven-year

prison sentence. More scandalous still, not one of China's Diaspora

poets and

novelists was invited, even though some of the country's most

distinguished

writers live abroad. "We must be very powerful and they are frightened

of

us," Qi Jiazhen, a fiery, seventy-year-old writer told me, at a meeting

of

Chinese writers in London to protest the fair's corrupt invitation

list.

"That is why they won't let us into the fair."

Fifty

writers attended the meeting, which took place the day before the fair

opened,

including well-known novelists like Ma Jian, author of Beijing Coma. Qi

Jiazhen

was one of three writers in the room who had served jail sentences in

China for

what they had written; she is the author of The Black Wall: The True Story of

Father -and Daughter: Two Generations of Prisoners, an account

of her own

eleven-year sentence and the one of twenty-three years imposed on her

father.

At the fair,

which closed on April 18, China's official presence was overwhelming,

its

stalls, desks, and book "displays taking up more space than those of

any

other country. At the information desk, staffed by young Chinese women

studying

in the UK, I asked whether Gao Xingjian, the Nobel laureate, would be

speaking.

None had heard of him. I said he lived just over the Channel in Paris.

One of the young women said, "Then he's not a Chinese, right?" I said

he was indeed, had lived most of his life there, and had resigned from

the

Party.

They looked

embarrassed. I then asked if Liu-Xjaobo would be attending. They all

edged away

except one, studying mathematics, who said, "I have my feelings about

him,

here, inside." I invited her to tell me what those feelings were, and

she

replied, "I better not." I then asked another young woman, behind the

desk of the main display of Chinese publications-on subjects ranging

from

technical matters to poetry-if Gao Xingjian's books were on show. She

hadn't

heard of him, but said she would ask "my boss." When she asked him in

Chinese if they had Gao's books he said, in English, that Gao wasn't a Chinese

and that, like all foreigners, "he lied about China." I asked

him what

sort of lies. He said in Chinese to his young assistant, "Don't talk to

this foreigner." I told him in Chinese I could understand every word he

had said, whereupon he told me, in English, "You're a shit." I replied,

"Bici, bici," which means,

in effect, the feeling is mutual.

To compensate

for the absence of dissident Chinese authors, the delegation running

the

Romanian stall offered their space to exiled Han, Tibetan, and Uighur

writers.

Ma Jian spoke: There are 118 Chinese publishers here; all are

mouthpieces of

the Communist Party. The writers they have invited are considered

beautiful by

the Party. No ugly person, like those of us here, can speak officially.

We

don't object to the writers who are invited, but until all of us are

free to

speak and write no Chinese writer is free.

John

Ralston-Saul, president of PEN International, also spoke, noting that

thirty-five

Chinese authors are in prison, some for many years, and that more than

a hundred

have been detained. "Why do they do it?" he asked. "Free

expression is the only way to solve any country's social- ills." The

official

PEN statement he handed out recalled "the many [writers] who live in

exile." For her part, Susie Nicklin, the British Council's director of

literature, told The Observer that

the writers approved and invited by Beijing are more representative

because

"they live in China and write their books there," in contrast with

"other writers [who] have left." To this, Yang Lian, one of China's

leading poets, who lives in London, told me: "What's

happening is that countries are becoming companies. And that's what the

British

Council is already, just a company cooperating with the Chinese

company."

What Chinese poets saw in the 1980s, Yang Lian observed,

was

a nation of cultural nihilists ... we had

failed to make a modern transformation of our own tradition. What we

saw

before us was something that could only be called

"Communist culture" ... the worst version of Chinese autocracy hidden

beneath Western revolutionary language.

Finally, I

went to the space where senior representatives of GAPP, the Chinese

publishing

bureau, were talking to the press. Madame Huang, who was representing

GAPP, pressed a stuffed panda into the hands of each reporter as they

were

introduced. "This is a symbol of China," she said, "friendly and

open." In Chinese I asked Madame Huang, who had already given me a

panda,

if either Gao Xingjian or Liu Xiaobo had been invited to appear at the

Book

Fair. She instantly snatched back my panda and hurried away. +

NYRB May 24,

2012

|