|

|

The Attic

Her brain is an attic where things

were stored over the years.

From time to time her face appears

in the little windows near the top of the house.

The sad face of someone who has been locked up

and forgotten about.

Gác Xép

Não của nàng thì là cái gác

xép

Nơi lưu cữu từ bao đời, đồ này vật nọ

Lâu lâu khuôn mặt của nàng hiện ra nơi khung

cửa nhỏ gần chỏm nhà

Bộ mặt buồn bã của 1 người bị khoá, nhốt, và quên

bỏ, từ đời nảo đời nào

Kafka’s Watch

from a letter

I have a job with a tiny salary of 80 crowns, and

an infinite eight to nine hours of work.

I devour the time outside the office like a wild beast.

Someday I hope to sit in a chair in another

country, looking out the window at fields of sugarcane

or Mohammedan cemeteries.

I don't complain about the work so much as about

the sluggishness of swampy time. The office hours

cannot be divided up! I feel the pressure

of the full eight or nine hours even in the last

halfhour of the day. It's like a train ride

lasting night and day. In the end you're totally

crushed.You no longer think about the straining

of the engine, or about the hills or

flat countryside, but ascribe all that's happening

to your watch alone. The watch which you continually hold

in the palm of your hand. Then shake. And bring slowly

to your ear in disbelief.

The Lightning Speed of the Past

The corpse fosters anxiety in men who believe

in the Last Judgment, and those who don't.

- ANDRE MALRAUX

He buried his wife, who'd died in

misery. In misery, he

took to his porch, where he watched

the sun set and the moon rise.

The days seemed to pass, only to return

again. Like a dream in which one thinks,

I've already dreamt that.

Nothing, having arrived, will stay.

With his knife he cut the skin

from an apple. The white pulp, body

of the apple, darkened

and turned brown, then black,

before his eyes. The worn-out face of death!

The lightning speed of the past.

http://www.tanvien.net/Portrait/Ray.html

http://www.tanvien.net/tgtp_02/Raymond_Carver.html

http://tanvien.net/new_daily_poetry/Carver_Page.html

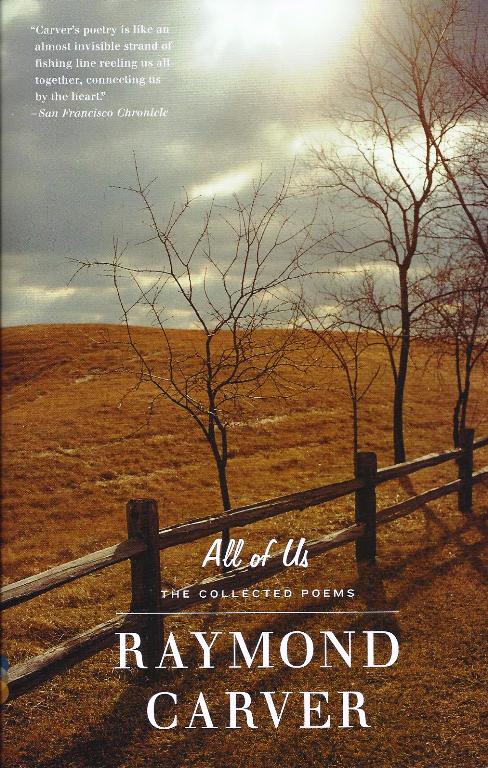

Raymond

Carver

Carver: Poems

Carver by Rushdie

Enright on Carver

Ray

AUTUMN

This yardful of the landlord's

used cars

does not intrude. The landlord

himself, does not intrude. He hunches

all day over a swage,

or else is enveloped in the blue flame

of the arc-welding device.

He takes note of me though,

often stopping work to grin

and nod at me through the window. He even

apologizes for parking his logging gear

in my living room.

But we remain friends.

Slowly the days thin, and we

move together towards spring,

towards high water, the jack-salmon,

the sea-run cutthroat.

AUTOMNE

Ce jardin plein des voitures

usagées du proprio

ne me dérange pas. Le proprio

lui-même n'est pas dérangeant. II reste courbé

toute la journée au-dessus d'un porte-pièces,

ou bien enveloppé par la flamme bleue

de la lampe à souder.

II fait attention à moi pourtant,

s'arrêtant souvent de travailler pour m'adresser

un sourire ou un signe de tête à travers le carreau.

[Il s' excuse

même d'avoir remisé sa tronconneuse

dans ma salle de séjour.

Mais nous restons amis.

Lentement les jours s'allongent, et nous

avancons ensemble vers le printernps,

vers la montée des eaux, le frai des saumons

et la truite anadrome.

MÙA THU Ở ĐÂY

ĐẸP NÃO NÙNG 2

Nguyễn

Quốc Trụ

MÙA THU Ở ĐÂY ĐẸP NÃO

NÙNG

Autumn

The wind wakes,

sweeps the thoughts from my mind

and hangs me

in a light that smiles for no one:

what random beauty!

Autumn: between your cold hands

the world flames.

1933

Octavio Paz: First Poems (1931-1940)

Mùa Thu

Gió thức dậy

Quét những ý nghĩ ra khỏi cái đầu của anh

Và treo anh

Trong ánh sáng mỉm cười cho chẳng ai

Cái đẹp mới dưng không, tình cờ làm

sao?

Mùa thu: giữa lòng bàn tay lạnh của em

Tình anh sưởi ấm

[nguyên văn, thế giới bập bùng ngọn lửa]

~~oOo~~

Here

My footsteps in this street

echo

in another street

where

I hear my footsteps

passing in this street

where

Only the mist is real

[1958-1961]

Đây

Tiếng bước chân của

tôi

trong con phố này

vọng lên

trong một con

phố khác

nơi

tôi nghe

những bước chân của mình

qua con phố này

nơi

Chỉ sương mù là có thực

~~oOo~~

Apollinaire: Alcools

Mùa thu bịnh

Mùa thu bịnh và

đáng mê làm sao

Mi sẽ chết khi bão thổi qua những vườn hồng

Khi tuyết xuống

Trong những vườn cây

Mùa thu đáng

thương, tội nghiệp

Chết trong cái màu trắng, trong cái giầu

sang

Của tuyết và của trái chín

Ở nơi cuối trời

Những cánh chim bồ cắt bay lượn

Bên trên những thuỷ thần già, tóc xanh

và lùn

chẳng bao giờ yêu

Ở nơi bìa rừng

Những con hươu thèm nhau, rền rĩ

Ui chao, mùa thu, mùa,

tôi mới yêu làm sao

Những tiếng thì thầm của nó

Những trái cây rụng xuống, không ai hái

Gió và rừng đều thi nhau khóc

Tất cả những giọt nước mắt, mùa thu, lệ thu, từng chiếc,

từng chiếc

Những chiếc lá con người dẫm lên

Một con tàu chạy

Và đời cứ thế mà trôi đi.

~~oOo~~

Automne

Dans le brouillard s'en vont un paysan cagneux

Et son bœuf lentement dans le brouillard d'automne

Qui cache les hameaux pauvres et vergogneux

Et s'en allant là-bas le paysan chantonne

Une chanson d'amour et d'infidélité

Qui parle d'une bague et d'un cœur que l'on brise

Oh! l'automne l'automne a fait mourir l'été

Dans le brouillard s'en vont deux silhouettes grises

Apollinaire

Mùa Thu

Trong sương mù, một người nhà

quê đi, chân liềng khiềng

Và con bò của anh ta lừng khừng đi trong sương

mù mùa thu

Lấp ló trong lớp sương mù là những thôn

xóm nghèo nàn và xấu hổ

Và trong khi đi như thế, anh nhà

quê ư ử hát

Một bài tình ca và sự không trung

thuỷ

Nói về một cái nhẫn và một trái tim

mà người ta làm tan nát

Ôi

mùa thu, mùa thu làm chết đi mùa hè

Trong sương mù cập kè

hai cái bóng xám

Nguyễn Quốc

Trụ dịch

(Nguồn : Tin Văn

www.tanvien.net )

trang nguyễn quốc trụ

art2all.net

Tượng Nữ

hoàng Elizabeth ở trung tâm thủ đô Ottawa dưới cơn

mưa cuối mùa thu.

Tượng Nữ

hoàng Elizabeth ở trung tâm thủ đô Ottawa dưới cơn

mưa cuối mùa thu.

Bếp Lửa Ottawa

2 Years Ago

See Your Memories

GOSSIP

IN THE VILLAGE

I told no one,

but the snows came, anyway.

They weren't even serious about it, at first.

Then, they seemed to say, if nothing happened,...

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/05/05/gossip-in-the-village

GOSSIP

IN THE VILLAGE

I told no one,

but the snows came, anyway.

They weren't even serious about it, at first.

Then, they seemed to say, if nothing happened,

Snow could say that, & almost perfectly.

The village slept

in the gunmetal of its evening.

And there, through a thin dress once, I touched

A body so alive & eager I thought it must be

Someone else's soul. And though I was mistaken,

And though we

parted, & the roads kept thawing between snows

In the first spring sun, &itwas all, like spring,

Irrevocable, irony has made me thinner. Someday, weeks

From now, I will wake alone. My fate, I will think,

Will be to have no fate. I will feel suddenly hungry.

The morning will be bright, & wrong.

- Larry Levis

The New Yorker,

April 5, 2014

Buôn chuyện làng

Tớ đếch nói

với ai, nhưng, dù sao, tuyết tới.

Lúc thoạt đầu, họ chẳng thèm ngay cả tỏ ra nghiêm

trọng, về chuyện đó.

Rồi có vẻ như là họ muốn nói, nếu chẳng

có gì xẩy ra,

Tuyết có thể nói điều đó & hầu như tuyệt

hảo

Ngôi làng

ngủ, trong màu đồng đỏ, của những buổi chiều của nó.

Và ở đó, qua cái áo dài mỏng,

một lần, tôi sờ vô

Một cơ thể sống ơi là sống & hăm hở, tôi nghĩ

Hẳn là linh hồn một người nào đó.

Và, tôi đã lầm.

Và chúng

tôi lên đường & những con lộ băng tan giữa tuyết

Trong mặt trời đầu tiên của mùa xuân &

tất cả, như mùa xuân

Vô phương huỷ bỏ, cái tếu táo, buồn cười

làm tôi càng thêm ốm tong teo.

Vài ngày, vài tuần, kể từ bây giờ

Tôi sẽ thức giấc một mình.

Số phần của tôi, tôi nghĩ,

Là đếch có số phần.

Bất thình lình, tôi cảm thấy đói.

Buổi sáng thì sẽ sáng ngời & lầm lẫn.

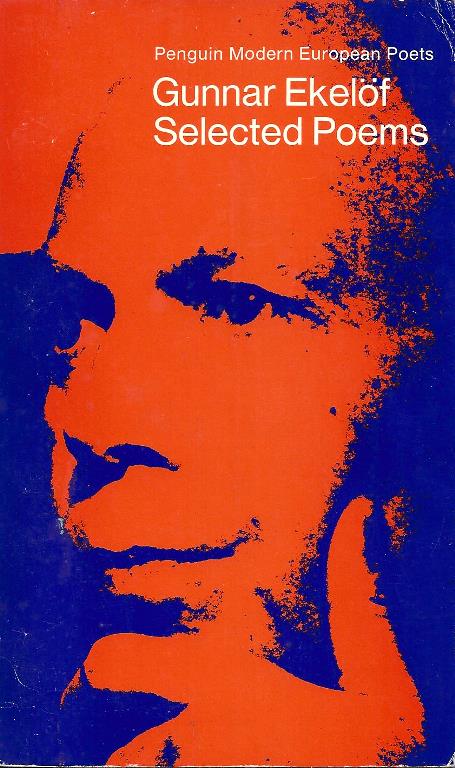

Tập thơ này, mua xon, chỉ vì

cái tên người dịch và viết Tựa: Auden.

Auden

được coi là sư phụ của Brodsky. Khi bị đày qua Tây

Phương, ông được sư phụ chờ đón ở.... sân ga.

Đúng ra là phi trường, nhưng giá như chờ ở sân

ga, tuyệt hơn, “trong khi chờ tầu hỏa", là 1 hình ảnh

hợp với Brodsky, và cùng với ông, là nước Nga.

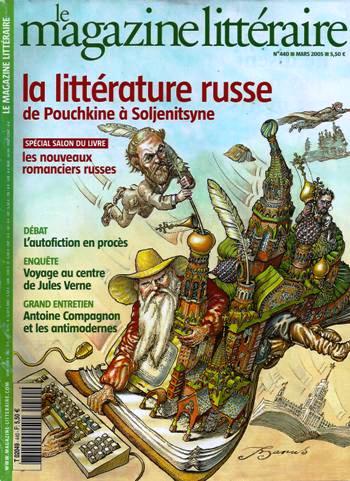

Bài “editô” của số báo Văn Học Tẩy, về văn chương

Nga, dùng cái tít này: En attendant le train!

Trong Khi Chờ Tầu Hỏa!

Nhân đọc mẩu viết về “tầu

hoả”, tức “xe lửa”, trên Blog NL, bèn nhớ tới số báo

này.

Bài "édito" thật tuyệt.

Cái tít làm nhớ đến Beckett, Trong Khi Chờ Godot, và đây

là dụng ý của tay viết.

Và của Gấu!

EN ATTENDANT LE TRAIN

MÉDITANT SUR TOLSTOI ET

DOSTOIEVSKI au fil d'un magistral essai (1), George Steiner ouvre une brève

parenthèse pour souligner le role stratégique des quais de

gare chez ces deux auteurs. Leurs trajectoires, si souvent opposées

et dont Steiner s'applique à minorer les divergences, se trouvent

ainsi réunies, en attendant le train, II ne faudrait pas toutefois

en conclure que le roman russe s'apparente à l'indicateur Chaix

et encore moins à une littérature de gare, encore que lire

Guerre et Paix dans le Transsibérien

demeure un projet séduisant. Et cohérent. Les héros

de Tolstoi comme ceux de Dostoievski aiment voyager par le train, Que

l'on songe à l'ouverture de L'ldiot, quand le prince

Muichkine et Rogojine approchent de Saint-Pétersbourg par le train

de Varsovie. Ou encore à la tragédie d'Anna Karénine

qui commence, comme elle finira, sur un quai de gare.

Vronsky, on le sait, part pour la guerre.

II existe d'autres destinations plus enviables. D'autant que le roman

russe profite de l'immensité de l'espace pour pousser ses héros

vers de lointaines et mythiques frontières, là où

campent les Cosaques, les tribus du Caucase, les vieux-croyants du Don

et de la Volga. Le héros tolstoien s'évade volontiers à

la campagne, et ce retour à la terre s'accompagne d'une résurrection

de l'âme. Le héros dostoievskien, pour sa part, cherche

son salut dans le royaume de Dieu, improbable destination que l'auteur

des Possédés conseillait ironiquement

de choisir plutôt en juin.

Quand, rompus de fatigue, les héros

restent à quai, c'est l'auteur qui part. Ainsi Tolstoi, abandonnant

au soir de sa vie de domicile conjugal pour retrouver les lieux de sa

jeunesse, fuyant vers le Caucase comme s'il voulait semer la mort qui

est à ses trousses. « Je m'en vais dans la solitude»,

écrit-il dans ses Carnets. Pour terminus, une

petite gare, à Astapovo, où il mourra en laissant sur sa

table de chevet deux livres, ultimes compagnons de voyage: Les Frères Karamazov et les Essais de Montaigne.

La Russie et l'Europe sont les deux patries

des auteurs russes. Tolstoi admirait Stendhal. De son coté,

Dostoievski avait lu avec passion Sand, Dickens, Balzac, Sue, Restif...

Reconnaissant sa dette envers la culture européenne, il faisait

dire à Ivan Karamazov: « Je veux voyager en Europe, Aliocha;

je veux sortir d'ici. Et pourtant, je sais que je ne trouverai qu'un

cimetière un très précieux cimetière, voilà

ce que c'est! » Quant à Gogol, il trouva sa Russie alors

qu'il pérégrinait à Paris, Rome ou Vevey.

Indifférente à tant de transports,

l'Europe à longtemps consideré avec froideur et réticence

les auteurs russes, On leur reprocha une débauche de pathos,

l'absence de contraintes esthétiques, trop de vie, trop de pages.

Comment faire face aces « grands monstres informes », selon

la redoutable expression d'Henry James? Tolstoi a écrit pas moins

de quatre-vingt-dix volumes et, jamais en mal d'inspiration, il se

risqua à bâtir une pièce de théatre en six

actes. Voulant rivaliser avec l'infinité, il faisait en sorte

que le dernier chapitre de chaque roman ménage un prélude

à l'oeuvre prochaine. II refusait de mettre un point final, et en

mit même trois pour éviter de tout à faire conclure

Guerre et Paix. Voilà l'un des miracles

de la littérature russe : les trains qui la traversent ne

s'arrêtent jamais.+

(1) George Steiner, Tolstoi ou Dostoievski, traduit de l'anglais par Rose Celli,

réed, 10/18, 2004.

Trở lại với tập thơ. Tuyệt.

Đi liền 1 bài

Foreword

Gunnar Bkelof was born in 1907 in Stockholm.

His father was a wealthy stockbroker who caught syphilis, became insane

and died while Bkelof was still a child; his mother was a member of

the petty nobility and does not seem to have shown him much affection.

Consequently, he had to find such happiness as he could in a private

dream world of his own. Of this early time he wrote:

My own childhood environment

was well-to-do but so far beyond the normal and so unrealistic that

there was good room for peculiar kinds of want .... I had books, music,

beautiful furniture around me, but they forced me to go long roundabout

ways before I could feel I had a legitimate right to them.

As Ekelof grew up,

he became engrossed in Oriental mysticism:

I learned to hate Europe and Christianity

and during the morning prayer at school I began to mumble Om mani

padme hum as a form of protest ...

In the Royal Library he discovered Tarjúmán

el-Ashwáq by Ibn el-Arabi which for a long time was his favorite book

and from which, he tells us, he first learned what is meant by Symbolism

and Surrealism. With the idea of emigrating to India, he went to London to

study at the School of Oriental Languages, but abandoned this scheme and

returned to Sweden to study Persian at the University of Uppsala. However,

a long illness prevented him from completing his studies. It was at this

time that he wrote his first poem:

One night I had an experience

that I would have to characterize as a form of ecstasy. It came over

me as a shower of shooting stars, and I remember staggering a bit on my

way home. As often on such occasions, I had had the usual orchestra playing

somewhere behind me, and I myself joined in with one instrument after

the other. Then it became a poem, my first fairly original one.

Ekelof's second great and lasting passion

was music and, in the 1920s, he went to Paris to study it, but soon

became absorbed by the problems of poetic language:

I placed one word beside another

and finally with a great deal of effort managed to construct a whole

sentence - naturally not one that' meant something' but one that was

composed of word-nuances. It was the hidden meaning that I was seeking

- a kind of Alchemie du verbe. One word has its meaning

and another word has its own, but when they are brought together something

strange happens to them: they have an in-between connotation at the same

time as they retain their original individual meanings . .. poetry is

this very tension-filled relationship between the words, between the

lines, between the meanings

It was in Paris, it would seem, that

he wrote many of the poems which appeared in his first book, Sent

pa Jorden (Late on the Earth), which was published in I932. This

he later described as a 'suicidal book":

I literally used to walk around

with a revolver in my pocket. Illegally, for that matter. In my general

despair I did everything possible to remain in my dream-world - or

to be quickly removed from it. I began to gamble and I lost my money,

which made my temporary return to Sweden quite definite.

Late on the Earth attracted little

critical attention, but by the time of the publication of Farjesang (Ferry

Song) in I941, he had become recognized as one of Sweden's leading poets.

The translations in this Penguin volume

are of two late works, Diurdn over Fursten av Emgión (Diwan

over the Prince of Emgión), 1965, and Sagan om Fatumeh

(The Tale of Fatumeh), 1966. His last volume, Vagvisare

till underjorden (Guide to the Underworld) was published in

1967. In 1968 he died of cancer of the throat.

The Prince of Emgión had appeared

in two earlier poems. Bkelof relates that, during a spiritualist seance

in Stockholm during the thirties, he had asked where his spiritual “I”

was to be found. The oracle, a drinking-glass placed upside down, replied:

'In Persia and his name is the Prince of Emgión.' Later, Ekelof

came to believe that this Prince was of Armenian-Kurdish stock, half a

Christian and half a Gnostic.

Diwan was begun in Constantinople

in 1965, and most or all of the poems were written within a period

of four weeks. , 'Dwan,' Ekelof wrote to a friend, 'is my greatest

poem of love and passion. I cannot touch it nor see it because I grow

ill when I see this blind and tortured man .... As far as I can understand,

someone has written the poems with me as a medium .... Really, I have

never had such an experience, or not one as complete.'

The character he here refers to is not

the Prince, but Digenis Acritas, the hero of an eleventh-century Byzantine

epic romance. Digenís was the son of an Arab father and a Byzantine

mother. Captured in battle, he was incarcerated in the prison of Vlacherne,

where he was tortured and blinded. In his suffering his principal consolation

is the Virgin, to whom he addresses passionate hymns. Though there are

references to what are obviously Christian icons, this figure is not the

Christian Madonna, but rather the Earth Mother, the Goddess known to us through

St Paul as the 'Diana of the Ephesians'. In Diwan another female

figure appears who is human, not divine, perhaps a wife, perhaps a sister

or daughter.

The Tale of Fatumeh is an equally

sad story. It tells of a generous, loving girl who becomes first a

courtesan and then the beloved of a prince, whose child she bears; she

is apparently deserted by him and brought to the Harem at Erechtheion,

but she is eventually thrown out of the Harem and spends a miserable

old age, selling herself to keep alive. Like Digenís, Patumeh

is sustained by her visions. Whatever has happened and may happen, no

disaster shall degrade her soul.

Like the Greek poet Constantine Cavafy,

Bkelof sets these poems in a bygone age. Different in sensibility as

they are - Cavafy is ironic and detached, Ekelof passionate and involved

- neither chooses the past as an escape: for both it is a means for

illuminating and criticizing the present. Although Ekelof was fascinated

by Byzantium, he never idealized it. 'Why,' he wrote in a letter,

'have I become interested in the Byzantine, the Greek life? Because

Byzantine life, traditionally and according to deep-rooted custom, is

like the political life in our cities and states. I am intensely interested

in it because I hate it. I hate what is Greek. I hate what is Byzantine

.... Diwan is a symbol of the political decadence we

see around us. Fatumeh is a symbol of the degradation,

the coldness between persons, which is equally obvious.'

Ekelof had a special numerological theory

and considered life an odd number and death an even number. His numerological

preoccupation is expressed in his division of The Tale of Fatumeh

into a nazm, a string of beads, and a tesbih; a rosary,

each consisting of twenty-nine numbered poems. This plan regrettably

had to be abandoned for this version. Some textual emendations have

also been made whenever Bkelof''s manuscripts have warranted such action.

W. H. AUDEN

LEIF SJOBERG

Penguin Modem European Poets

Advisory Editor: A. Alvarez

Selected Poems: Gunnar Ekelof

Gunnar Ekelof was born in Stockholm in 1907. Intending to

become a pianist, he studied music in Paris, and then took up Oriental

studies in London and U ppsala. His verse was from the first a highly

individual mixture of esoteric, even cryptic allusions and simple, homely

confessions. His first book, Late on the Earth (1932),

he called' a suicidal book'. It reflects an outlook fundamentally divided,

in which subject and object move unrelated as in a trance. It was regarded

by sonie as inspired by French Surrealism, a charge Ekelof denied. Nevertheless

it brought radical innovation to the forms of Swedish poetry. Ferry

Song (1941) and Non Serviam (1945) oscillate between mysticism

and intellectualism. In Strountes (1955), Opus Incertum (1959)

and A Night in Otolac (1961), he fashioned a poetry patently anti-aesthetic.

In A Moelna Elegy (1960) he dwells on the plurality

of times past and future, and of death in life. The remarkable Byzantine

triptych Diwan Fatumeh, Vagvisare (1965-7),

was dedicated to love absorbed by mystical identification, In addition

to his own fifteen books of verse Ekelof translated many foreign poets

into Swedish, amongst them Eliot.joyce, Auden, Baudelaire and Rimbaud.

By the time he last visited Asia Minor in 1965 he was acknowledged by

many as the greatest lyric poet Sweden has produced. He died of cancer

in 1968 and his ashes rest at the ancient city of Sardis.

You have the face of a dwarf-woman

With blue eyes, evil eyes

You are ugly and deformed

But what shall a man do

If not amuse himself?

The child you will bring forth

Between your stunted legs

will not live

Because I shall disown it

Angel! Forgive him and me

Who to satisfy my hunger

Must love at any price

Even the lowest.

Em có khuôn mặt của một

người đàn bà lùn tịt

Mắt xanh, mắt quỉ, mắt ma

Em xấu xí, méo mó

Nhưng 1 thằng đàn ông Bắc Kít như anh,

thì biết làm gì nếu không.... tự sướng?

Đứa con trai mà em mang tới cõi đời này,

từ cái cặp giò còi cọc của mình

Sẽ không sống

Anh sẽ không nhận nó là con

Thiên Sứ ơi! Hãy tha thứ cho nó và

tôi

Kẻ, để thoả mãn cơn đói của mình

Phải yêu với bất cứ giá nào

Ngay cả kẻ thấp kém, tồi tệ nhất.

Đọc,

thì bỗng nhớ đến tên Bắc Kít, óc bị thiến

1 mẩu, chê Jolie, xấu, ngu, miệng như cái gạt tàn!

Hay tên Lăng Băm!

Trăng

THE MOON

for Maria Kodama

There is such loneliness

in that gold.

The moon of the nights is not the moon

Which the first Adam saw. The long centuries

Of human vigil have filled her

With ancient lament. Look at her. She is your mirror.

[Trans. Willis Barnstone]

Trăng

Có nỗi cô tịch

như thế, ở trong khối vàng đó.

Trăng đêm không phải trăng Adam, thuỷ tổ giống người,

nhìn.

Những thế kỷ dài ăn chay cầu nguyện của con người

Đã tẩm vào nàng nỗi sầu vạn cổ.

Hãy nhìn nàng kìa.

Nàng là tấm gương của em đó.

JORGE

LUIS BORGES

Pythagoras, an old tradition holds,

used to write his verse in blood on a mirror.

Men looked to its reflection in the moon's

hoping thus to make his meaning clearer.

[Bản Penguin]

Pythagoras

(according to one tradition)

used blood to write upon a mirror,

and men read it by reflection

in that other mirror called the moon.

-Translated

by EDWIN HONIG

Pythagore

thường làm thơ bằng cách

Rỏ máu đầu ngón tay lên một tấm gương

Người đời sau nhìn phản chiếu trong trăng

Hy vọng nghĩa của nó trong sáng hơn

[Dịch sái đi, theo cách hiểu THNM của GCC]

The Moon

The story goes that in those far-off times

when every sort of thing was taking place-

things real, imaginary, dubious things-

a man thought up a plan that would embrace

the universe entire in just one book.

Relentlessly spurred on by this vast notion,

he brought off the ambitious manuscript,

polishing the final verse with deep emotion.

All set to offer thanks to his good fortune,

he happened to look up and, none too soon,

beheld a glowing disk in the upper air,

the one thing he'd left out-the moon.

The story I have told, although made up,

could very well symbolize the plight

of those of us who cultivate the craft

of turning our lives into the words we write.

The essential thing is what we always miss.

From this law no one will be immune

nor will this account be an exception,

of my protracted dealings with the moon.

Where I saw it first I do not know,

whether in the other sky that, the Greeks tell,

preceded ours, or one fading afternoon

in the patio, above the fig-tree and the well.

As is well known, this changing life of ours

may incidentally seem ever so fair,

and so it was on evenings spent with her

when the moon was ours alone to share.

More than moons of the night, there come to mind

moons I have found in verse: the weirdly haunting

dragon moon that chills us in the ballad

and Quevedo's blood-stained moon, fully as daunting.

In the book he wrote full of all the wildest

wonders and atrocious jubilation,

John tells of a bloody scarlet moon.

There are other silver moons for consolation.

Pythagoras, an old tradition holds,

used to write his verse in blood on a mirror.

Men looked to its reflection in the moon's

hoping thus to make his meaning clearer.

In a certain ironclad wood is said to dwell

a giant wolf whose fate will be to slay

the moon, once he has knocked it from the sky

in the red dawning of the final day.

(This is well known throughout the prophetic North

as also that on that day, as all hope fails,

the seas of all the world will be infested

by a ship built solely out of dead men's nails.)

When in Geneva or Zurich the fates decreed

that I should be a poet, one of the few,

I set myself a secret obligation

to define the moon, as would-be poets do.

Working away with studious resolve,

I ran through my modest variations,

terrified that my moonstruck friend Lugones

would leave no sand or amber for my creations.

The moons that shed their silver on my lines

were moons of ivory, smokiness, or snow.

Needless to say, no typesetter ever saw

the faintest trace of their transcendent glow.

I was convinced that like the red-hot Adam

of Paradise, the poet alone may claim

to bestow on everything within his reach

its uniquely fitting, never-yet-heard-of name.

Ariosto holds that in the fickle moon

dwell dreams that slither through our fingers here,

all time that's lost, all things that might have been

or might not have-no difference, it would appear.

Apollodorus let me glimpse the threefold shape

Diana's magic shadow may assume.

Hugo gave me that reaper's golden sickle

and an Irishman his pitch-black tragic moon.

And as I dug down deep into that mine

of mythic moons, my still unquiet eye

happened to catch, shining around the corner,

the familiar nightly moon of our own sky.

To evoke our satellite there spring to mind

all those lunar cliches like croon and June.

The trick, however, is mastering the use

of a single modest word: that word is moon.

My daring fails. How can I continue

to thrust vain images in that pure face?

The moon, both unknowable and familiar,

disdains my claims to literary grace.

The moon I know or the letters of its name

were created as a puzzle or a pun

for the human need to underscore in writing

our untold strangenesses, many or one.

Include it then with symbols that fate or chance

bestow on humankind against the day-

sublimely glorious or plain agonic-

when at last we write its name the one true way.

-A.S.T.

Penguin ed

|