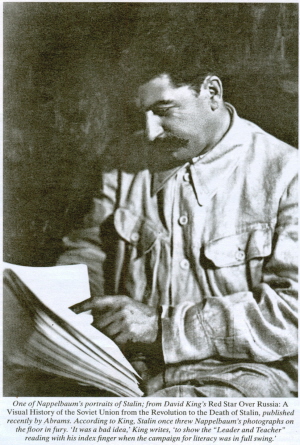

Osip

Mandelstam; photograph

by Moses Nappelbaum, known for his portraits of St. Petersburg's

writers,

including Anna Akhmatova and Boris Pasternak, as well as his portraits

of

Trotsky, Lenin, and Stalin

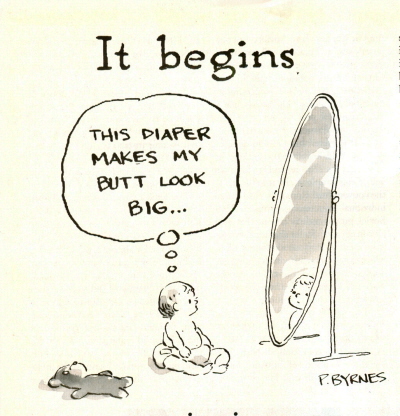

One of

Nappelbaum's portraits

of Stalin; from David King's Red Star Over Russia: A Visual History of

the Soviet Union from the Revolution

to the Death of Stalin,

published recently by Abrams. According to King, Stalin once threw

Nappelbaum's

photographs on the floor in fury. 'It was a bad idea,' King writes, 'to

show

the" Leader and Teacher" reading with his index finger when the

campaign for literacy was in full swing.'

NYRB

June 10, 2010

Reading Mandelstam on Stalin

José Manuel Prieto

EPIGRAM

AGAINST STALIN

We live

without feeling the country beneath our feet,

our words are inaudible from

ten steps away.

Any conversation, however

brief,

gravitates, gratingly, toward the Kremlin's mountain man.

His greasy fingers are thick

as worms,

his words weighty hammers

slamming their target.

His cockroach moustache seems

to snicker,

and the shafts of his

high-topped boots gleam.

Amid a

rabble of

scrawny-necked chieftains,

he toys with the favors of

such homunculi.

One hisses, the other mewls,

one groans, the other weeps;

he prowls thunderously among

them, showering them with scorn.

Forging decree after decree,

like horseshoes,

he pitches one to the belly,

another to the forehead,

a third to the eyebrow, a

fourth in the eye.

Every

execution is a carnival

that fills his broad Ossetian chest with delight.

-Translated

by Esther Allen

from Jose Manuel Prieto's Spanish version*

*The

Russian and Spanish texts

of the poem appear online at www.nybooks .com.

Strongman

MICHA

LAZARUS

đọc

Robert

Littell

THE STALIN EPIGRAM

304pp. Duckworth Overlook.

£14.99. 9780715639030

In November 1933,

Osip Mandelstam composed what would become known as "The Stalin

Epigram", a sixteen-line poem openly critical of the "Kremlin

mountaineer", the "murderer and peasant-slayer", Joseph Stalin.

In May 1934, Mandelstam was arrested for "countertenor activity" and

interrogated for two weeks, but was miraculously spared execution or

imprisonment following an edict from on high to "isolate and

preserve". He and his wife, Nadezhda, spent three years sentenced to

exile

from major cities, and lived peripatetically among friends and around Moscow

for a further year on their return. In May 1938, however, Osip was

arrested

once more, and sentenced to a camp for five years. Shipped to Vladivostok,

he was able to send a single note to his brother requesting "proper

clothes"; he did not survive the winter. Nadezhda outlived him by

forty-two years, eventually reconstituting much of his poetry from

memory.

Such details became known in the West largely thanks to Nadezhda's

magnificent

memoir, Hope Against Hope (1970). An admirer of that book, Robert

Littell met

Mrs Mandelstam in 1979, towards the end of her life, a meeting he

describes in

the epilogue to The Stalin Epigram. The novel reconstructs the events

of the

four years from Mandelstam's composition of the "epigram" to his

death by means of a fictionalized· version of the contemporary voices

of Osip

and Nadezhda and their close friends Anna Akhmatova and Boris

Pasternak, and

the wholly fictional voices of Stalin's chief bodyguard, a beautiful

young

actress connected to the Mandelstam, and a sweet-natured weightlifting

champion

and circus strongman whose experiences of Stalinist criminal justice

are

compared to those of the highly strung and sensitive Osip.

Most of the story takes place around the time of Mandelstam's first

arrest. The

couple's poetic creativity and sexual liberality are set against the

destructive and repressive Soviet bureaucracy, driven by a Stalin who

is more

physically decayed each time he appears. Littell doesn't stray far from

the

memoirs: his embroidery adds color and pace to a story much of whose

imperturbable horror derives from the banality of the state machinery.

Color and pace, however, oddly lessen that horror. In order to

translate from

memoir to novel, Littell situates at the thematic centre of the novel a

conflict between the sword and the pen, Stalin's steel mortality and

Mandelstam's poetic immortality.

The connection between the two, who in reality never met, is elaborated

in

fictional sequences of half-lucid delusions experienced by Mandelstam

under

duress. This is all very well for a story familiarly structured around

agency

and personality, protagonist, antagonist, tragic arc and fatal flaw; as

such,

Littell' s version is a swift and engaging piece of fiction. But the

macabre

pressure of the times is lifted in his account, as the bureaucratic

impersonality of events is transformed into a straightforward battle of

wills.

The novel thus squanders the opportunity offered by historical fiction

to

vivify the past and populate its silences. The "voices" here shift

uncomfortably between intimacy and expository formality, and sound

artificial;

the fictional characters imaginatively recreate the events from

multiple

perspectives, but (with the exception of Fikrit, the strongman) are too

typical

to add much. "You have to have lived through the thirties to

understand",

says Akhmatova in the novel, "and even then you don't understand."

Perhaps this is true, although Nadezhda Mandelstam's retelling was both

incisive and articulate. The Stalin Epigram is an entertaining,

well-researched

introduction, but the real story is in the memoirs.

TLS June 4 2010

Robert

Littell chuyển bài thơ “Vịnh Stalin” (1)

thành tiểu thuyết.

(1)

THE STALIN EPIGRAM

Mandelstam's

poem on Stalin

(November 1933) (1)

We

live, deaf to the land

beneath us,

Ten steps away no one hears

our speeches,

But where there's so much as

half a conversation

The Kremlins mountaineer will

get his mention. 2

His fingers are fat as grubs

And the words, final as lead

weights, fall from his lips,

His cockroach whiskers leer

And his boot tops gleam.

Around him a rabble of thin-necked leaders—

fawning half-men for him to

play with.

They whinny, purr or whine

As he prates and points a

finger,

One by one forging his laws, to be flung

Like horseshoes at the head,

the eye or the groin.

And every killing is a treat

For the broad-chested Ossete.

3

1. This

poem, which Mrs.

Mandelstam mentions on page 12 and at many other points, is nowhere

quoted in

full in the text of her book.

2. In the first version, which came into

the

hands of the secret police, these two lines read:

All we hear is the Kremlin

mountaineer,

The murderer and

peasant-slayer.

8. "Ossete." There

were persistent stories that Stalin had Ossetian blood. Osseda is to

the north

of Georgia in the Caucasus. The people, of Iranian stock, are

quite

different from the Georgians.

Mandelstam: Chân Dung Bác Xì [Tà Lỉn]

Chúng

ta sống, điếc đặc trước mặt đất bên dưới

Chỉ cần mười bước chân là

chẳng ai nghe ta nói,

Nhưng ở những nơi, với câu chuyện nửa vời

Tên của kẻ sau cùng trèo tới

đỉnh Cẩm Linh được nhắc tới.

Những ngón tay của kẻ đó mập như những con

giun

Lời nói nặng như chì rớt khỏi

môi

Ánh mắt nhìn đểu giả, râu quai nón-con gián...

Bài thơ

trên có nhiều bản

khác nhau. Trên, là từ hồi ký "Hy Vọng Chống lại Hy Vọng", của vợ nhà

thơ, Nadezhda Mandelstam.

Làm sao

Ông đã làm sao...

Tố Hữu

*

Vào tháng 11 năm 1933, Osip

Mandelstam sáng tác bài thơ trứ danh “Vịnh Stalin”, ‘người leo núi Cẩm

Linh’,

‘kẻ sát nhân tên làm thịt dân quê’. Tháng Năm 1934, ông bị bắt vì tội

'phản cách

mạng', bị tra hỏi trong 2 tuần, nhưng lạ lùng làm sao, do lệnh trên ban

xuống,

không bị làm thịt hay bỏ tù, mà chỉ bị ‘cách ly nhưng đừng để chết’.

Hai vợ chồng

trải qua 3 năm lưu vong ra khỏi những thành phố lớn; khi trở về, sống

giữa đám

bạn bè lòng vòng ở Moscow.

Tháng Năm 1938, ông chồng bị bắt trở lại, kết án 5 năm tù, và lần này

bị đầy đi

Vladivostok, chỉ kịp gửi một cái note, cho ông em/anh, gửi ‘quần áo

sạch’; ông

không thoát được mùa đông tại đó. Bà vợ sống dai hơn ông chồng 42 năm,

nhẩn nha

nhớ lại thơ chồng. Chúng ta được biết những chi tiết hiếm quí đó là qua

hồi ký tuyệt

vời của bà vợ, “Hy vọng chống lại hy vọng”

Là một độc giả mê cuốn hồi ý trên,

Robert Litell gặp bà vợ nhà thơ vào năm 1979, cuộc gặp gỡ ông kể lại ở

cuối cuốn tiểu thuyết của

ông, một giả tưởng tái tạo dựng những sự kiện trong 4 năm, từ khi nhà

thơ trước

tác bài thơ vịnh Xì Ta lin, cho tới cái chết của ông, cộng thêm vào đó

là những

giọng nói của Osip, của bạn bè của ông, của thời của họ, cộng giọng nói

giả tưởng

hóa của tay trùm cận vệ Xì….

Tribute

to Hoàng Cầm

Có 2

cách đọc Nguyễn Tuân?

Không chỉ NT, mà còn Hoàng Cầm, thí dụ.

Nhưng với HC có tí khác.

Nói rõ hơn, VC, sĩ phu Bắc Hà đúng hơn, đọc HC, khen thơ HC, là cũng để

thông

cảm với cái hèn của tất cả.

Của chung chúng ta! (1)

1. Tình

cờ ghé Blog của me- xừ Đông B, ông ta gọi cái món

này là 'mặc cảm dòng chính'!

Hình như tụi Mẽo cũng có thứ mặc cảm này, 'chỉ sợ mình Mẽo hơn tên hàng

xóm'.

Anh

VC thì cũng rứa! Nào là phục hồi nhân phẩm cho Ngụy, nào là em về đâu

hỡi em khi đời không chút nắng, đời gọi

em biết bao lần!

Khổ một nỗi, khi chúng mất nhân phẩm thì không thể nào phục hồi

được!

"Tớ

phục vụ một

cái nghĩa cả cà chớn, và tớ nhận tiền từ nhân dân Bắc Kít mà tớ lừa bịp

họ với những

bài thơ 'lá liếc' nhảm nhí của tớ. Tớ là một tên bất lương. Nhưng mà

này, bản thân tớ thì

là cái thống chế gì ở đây? Tớ chỉ là một hạt cát trong Cái Ác Bắc Kít…

Đây

là lỗi

lầm của cái thời mà có tớ sống ở trong đó”!

Hà, hà!

RUINED CHOIRS

How did Shostakovich's music

survive Stalin's Russia?

For genuine

dissidents, such as Solzhenitsyn and

Brodsky, Shostakovich was part of the problem. In an interview,

ironically,

with Solomon Volkov, Brodsky attacked the effort to locate "nuances of

virtue" in the gray expanses of Shostakovich's later life. Such a career

of compromise, Brodsky said, destroys a man instead of preserving him.

"It

transforms the individual into ruins," he said. "The roof is gone,

but the chimney, for example, might still be standing."

Cái trò ‘dạng háng’, ‘biển

một

bên, tớ một bên’… huỷ diệt một con người thay vì giữ được nó… Nó biến

con người

thành tro than, điêu tàn… Mái nhà thì mất mẹ nó rồi, nhưng cái ống

khói, có thể

vưỡn còn!

Note: Cái đoạn gạch đít ở

trên, áp dụng vào đám tinh anh Bắc Hà [HC, LD... trừ Hữu Loan], thật

hợp!

Late at

night, Ragin broods

over his condition: "I am serving a bad cause, and I receive a salary

from

people whom I deceive. I am dishonest. But then I am nothing by myself,

I am

only a small part of a necessary social evil. . . . It is the fault of

the time

I live in." He finds solace in the thought that suffering is universal

and

that death destroys all human aspirations in the end. Immortality, he

says, is

a fiction. When he dies, of a sudden stroke, he is mourned by no one.

At that

point, the resemblance to Shostakovich breaks down.+

Cái

‘xịp’ này làm

cho khẩu súng của tớ bự hẳn ra!

The New

Yorker Mar 20, 2000