|

Nhân

"Meursault, Phản Điều Tra" đợp Goncourt (1)

Camus vs Meursault, Phản

Điều Tra

Tờ TLS,

Jan 15, 2010, mục Tạp

Ghi, tiểu mục Lễ lạc văn học, Literary Anniversaries: Năm mươi năm

trước Camus

tử nạn xe hơi trên đường đi Paris, chiếc xe hơi của ông, Facel Vega

HK500, một địch

thủ của Aston Martin vào thời kỳ đó. Tháng Nov. cùng năm nhà văn Mẽo ly

hương

Richard Wright mất tại bệnh viện Eugène Gibez, nằm trên con phố

Vaugirard.

Camus 46 tuổi., Wright 52.

Thế rồi tờ báo viết tiếp: Cái chuyện bạn xục xạo để tìm ra một điều gì mới về Camus, thì kể như zéro, bởi vì ông này là nhà văn được tìm hiểu [researched] nhiều nhất trong thế kỷ vừa qua. Wright cũng không phải là nhà văn vô danh, tuy thế giá không bằng Camus, nhưng cũng đã có tới năm cuốn tiểu sử khác nhau về ông. Hi vọng độc nhất, của chúng ta là, tại sao không nối hai ông này lại, để tìm ra một điều gì mới? Có, thật! Wright là một “thằng bé da đen” (a “black boy”: tên cuốn tiểu sử của ông), từ Bạn có biết tên tác phẩm là gì không? The Outsider (1953). Đúng cái tít cuốn của Camus được dịch qua tiếng Anh, tại Anh, trong khi tại Mẽo, nó có tên là The Stranger. (b) Bận lòng Chắc bạn biết câu ca dao thần sầu: Em như cục kít

trôi sông [Nhớ đại khái] Và kinh nghiệm

này: Thịt chó phải hai lửa mới ngon.

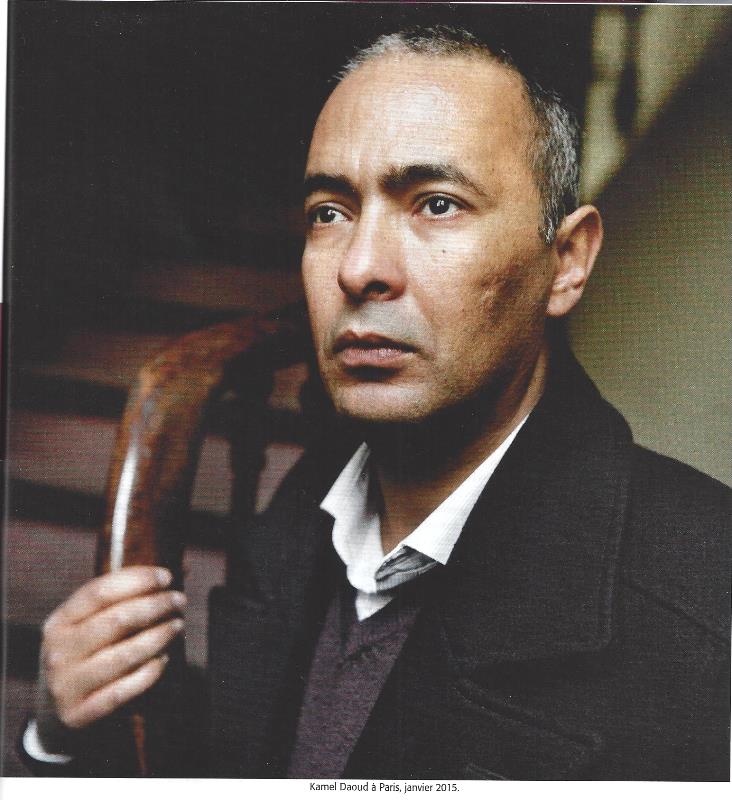

Kamel Daoud, prix Goncourt

du Premier roman Dans

"Meursault, contre-enquête", le journaliste et romancier algérien

proposait une relecture de "l'Etranger" de Camus. Le journaliste et romancier algérien Kamel Daoud a

reçu ce mardi 5 mai le

prix Goncourt du Premier roman pour «Meursault, contre-enquête» (Actes

Sud).

Dans ce spin-off de «l’Etranger», Daoud fait parler le frère de l’Arabe

tué par

Meursault dans le livre d’Albert Camus. Il donne un nom à cet illustre

inconnu,

Moussa, et raconte son histoire - manière de relire un classique sous

l’angle

du non-dit colonial. L’autre côté de l’histoire, en somme. Dans une récente interview au «New Yorker», Daoud,

célèbre en Algérie pour ses chroniques

tonitruantes, présente son livre comme «une

manière d’analyser l’œuvre de Camus, […] de la faire relire

par un

Algérien et par des lecteurs d’aujourd’hui.» Il ne faudrait pas résumer le roman à cette seule

démarche. Il a sa propre

histoire à raconter, celle de Haroun, le frère de Moussa. Il parle sa

propre

langue, bien plus ronde que la camusienne. Mais c’est bien l’ouverture

du

roman, dans laquelle le narrateur reproche à Camus d’avoir glosé sur

l’absurdité de la condition humaine en taisant la violence de la

condition

coloniale, qui s’est imposée comme le texte le plus fort paru l’année

dernière. Sorti en 2013 en

Algérie

et en juin dernier chez nous, le roman de Kamel Daoud a connu un très

joli

succès. Il a notamment été finaliste du grand Goncourt, en novembre, et

a reçu le prix des Cinq

Continents. Aujourd’hui, tandis

que son

auteur se trouve menacé par un appel à la

fatwa, il s’exporte. Il paraîtra

en juin aux Etats-Unis, où «l’Etranger» est un classique révéré,

sous le titre «The Meursault

Investigation». L'Académie Goncourt a par ailleurs remis d'autres prix. Le prix de la Poésie/Robert Sabatier, lui, va à William Cliff, et celui de la Nouvelle à Patrice Franceschi pour «Première personne du singulier» (Points Seuil). Sách

Báo Mới [new]

Nhân nói về

tác giả gối đầu giường, thì, với Gấu, còn có Camus. Đọc hồi mới lớn,

quá mê, khác

hẳn ông anh TTT. Khi Camus mất vì tai nạn xe hơi, TTT đi 1 bài thật là

nặng nề

về Camus, kết thúc bài viết bằng 1 câu thật là nặng nề, cái chết của

Camus đóng

chặt ông vào quá khứ, nhớ đại khái. Hậu thế cho

thấy TTT sai lầm về Camus. Thế giá của Camus, ngày càng sáng chói. Thái

độ của

Camus, khi chê Camus, tương tự Vargas Llosa, nhưng ông Nobel này có dịp

nhận ra

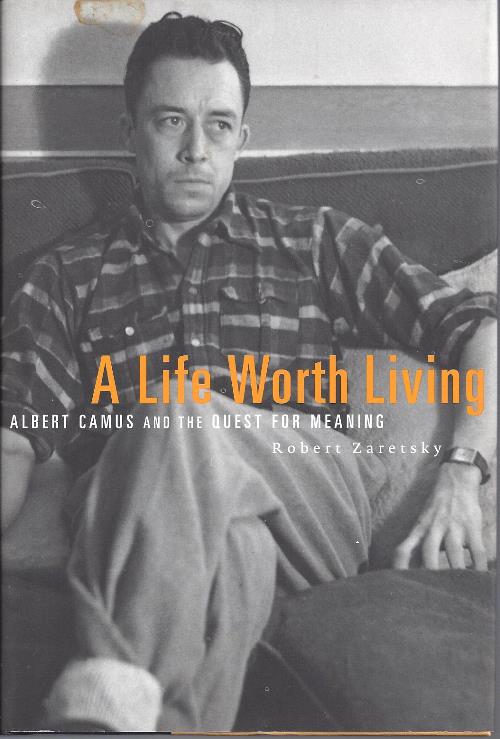

sai lầm của mình.  Camus @ 100 "Một đời đáng sống". Cuốn này cũng tuyệt lắm. Camus rất mê Nietzsche, nhưng chính cú Lò Thiêu làm ông khựng lại và đọc lại Nietzsche, như đoạn sau đây cho thấy: Camus first discovered Friedrich Nietzsche as a teenager- his university professor and mentor, Jean Grenier, made the introductions-and his first published essay, edited by Grenier and published in the journal Sud, was on Nietzsche and music. His lifelong engagement with Nietzsche, admiring but critical, sprawls across his notebooks. "I owe to Nietzsche a part of who I am," he acknowledged, gratefully. What Camus most admired was Nietzsche's slashing and mordant style, as well as his fierce clarity about a world that no longer supported the religious or metaphysical fictions with which humankind had burdened it. In The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus praises Nietzsche for having banished all hope for the future: "Nietzsche appears to be the only artist to have derived the extreme consequence of an aesthetic of the Absurd, inasmuch as his final message lies in a sterile and conquering lucidity and an obstinate negation of any supernatural consolation.” Casting himself as the surveyor of the varieties of nihilism flowering in our emptied cosmos, Nietzsche had the courage to call a void a void. Yet, he was a nihilist not by vocation, but by necessity: "He diagnosed in himself, and in others, the inability to believe and the disappearance of the primitive foundation of all faith-namely, the belief in life." Michel Onfray notes that Camus, a serious reader of Nietzsche, was nevertheless not a Nietzschean." By the time he published The Myth of Sisyphus Camus discovered that Nietzsche had dazzled other readers apart from himself, but with catastrophic consequences. In a world relieved of God and morality, everything was indeed permitted. Under the sun of Algiers, the embrace of fate-Nietzsche's amor fati, his Zarathustrian "Yes!" to all joys and all woes-dovetailed with Camus' youthful love of the world. But the iron sky over Auschwitz, Camus insisted, forced us to reconsider the ways in which yet others had interpreted Nietzsche. We know, Camus announced, Nietzsche's "posterity and what kind of politics were to claim the authorization of the man who claimed to be the last anti-political German. He dreamed of tyrants who were artists. But tyranny comes more naturally than art to mediocre men." And yet Nietzsche remained with Camus to the end. On January 2, 1960, when the car in which Camus was driving smashed into the plane tree alongside the road, killing both him and the driver, his friend Michel Gallimard, Camus' briefcase was flung several yards from the car. It contained his identity papers, a copy of Shakespeare's Othello) the manuscript for The First Man and a copy of The Gay Science. In this collection of aphorisms, Nietzsche jousts with Socrates, the philosopher who never wrote, yet at the same time never seemed to be short of words. Not only was Socrates "the wisest chatterer of all time," Nietzsche remarks, "he was equally great in silence." He then laments, ironically, that Socrates failed to be silent when it was most essential: as he died, he uttered his famously elusive remark to his friend Crito: "I owe Asclepius a rooster." For Nietzsche, this meant nothing less than that even Socrates, the most cheerful and courageous of men, nevertheless "suffered life." As a result, Nietzsche concluded: "We must overcome even the Greeks!"  Được mê nhất trong số

những nhà văn Tẩy (a) Note: TV sẽ

đi hai bài trên, nhân năm sắp tới, 2013, năm nay, là kỷ niệm 100 năm

năm sinh của

Camus, 1

trong những ông Thầy của Gấu hồi mới lớn. Bò lên rừng phò đao phủ

thủ HPNT! « Camus paie

pour sa rectitude, sa droiture, la justesse de ses combats, il paie

pour son

honnêteté, sa passion pour la vérité. » Résistant au

mirage du communisme Sun, Dec 23, 2012 Thư Chào hỏi K/G ông Cà

Chớn,

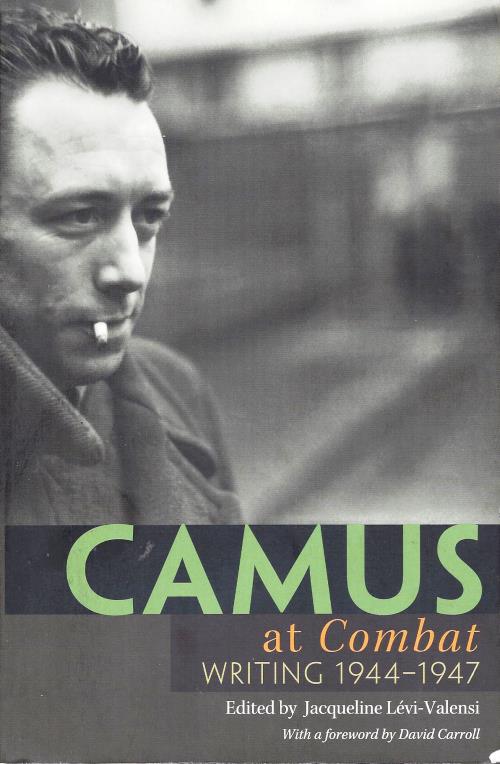

Hai cuộc chiến, với Pháp, và với Mẽo, cuộc chiến đầu thì còn có thể đổ cho dã tâm của anh Tây muốn trở lại Việt  FOREWORD Albert

Camus-Political Journalist: Democracy in an Age of Terror Our

twentieth century is the century of fear.... We live in terror. -ALBERT

CAMUS, "The

Century of Fear" (Combat, November 19, 1946) I have

always believed that if people who placed their hopes in the human

condition

were mad, those who despaired of events were cowards. Henceforth there

will be

only one honorable choice: to wager everything on the belief that in

the end

words will prove stronger than bullets. Tôi

luôn luôn tin rằng,

nếu những kẻ đặt hy vọng vào phận người - khùng,

thì những kẻ quá chán sự kiện, hèn. -ALBERT

CAMUS, "Toward

Dialogue" (Combat, November 30, 1946) Non-fiction - Camus at "Combat": Writing 1944-1947 by Albert Camus, edited by Jacqueline Levi-Valensi ( … Loại không giả tưởng, tôi chọn cuốn “Camus tại báo Combat", gồm những bài bình luận, và những bài viết khác, xuất hiện vào lúc thật nguy hiểm cho người viết, trên tờ nhật báo chui tại một nước Pháp bị Nazi chiếm đóng. Mỗi dòng viết, chứa trong nó, sự tổng hợp kỳ tuyệt, của niềm tin say mê và của tính khách quan, trong một sức mạnh trí tuệ, chính nó làm rạch ròi ra cái tài năng sáng tạo của Camus, ở trong những cuốn tiểu thuyết, Dịch Hạch và Kẻ Xa Lạ. Vừa là chủ bút vừa là ký giả, ông viết, về tiền đề, tốt cho thời kỳ [nước Pháp bị] Chiếm Đóng, và còn là một dự báo cho thời hiện tại của chúng ta mà ông chẳng còn sống để chứng nghiệm: “… sự cáo chung của những ý thức hệ đè lên chúng ta, nói rõ hơn, sự cáo chung của những không tưởng tuyệt đối, chúng tự huỷ chúng, và trong khi tự huỷ, chúng còn đòi cái giá nặng nề khi muốn có phần trong thực tại lịch sử”. Sau chiến tranh, ông viết về Algeria, điều được coi là tốt, không chỉ cho cựu xứ sở thực dân thuộc địa này mà còn cho những đế quốc thực dân thuộc địa khác: “Sự thất bại không kết thúc một cách hoà bình chủ nghĩa thực dân thuộc địa, sau khi Đệ Nhị Thế Chiến chấm dứt… là một thất bại nghiêm trọng, nếu không muốn nói, tối nghiêm trọng, cho chính nền dân chủ của nước Pháp”. * Cuộc chiến chống Mẽo, có rất nhiều “uẩn khúc”, và sau đây là những gợi ý của "Gấu nhà văn", liên quan tới cuộc thánh chiến thứ nhì này. Thứ nhất, tụi mũi lõ không rành lịch sử dân Mít. Cuộc chiến thứ nhì liên quan tới gốc gác của giống dân Mít, và, có thể nói, dân Mít không làm sao tránh khỏi cuộc chiến này. Có dân Mít, là để thực hiện cuộc chiến đó! Về cái vụ liên can đến gốc gác, thì em Rose, Bông Hồng, trong Y Sĩ đồng quê của Kafka, có đưa ra một lời giải thích. Em người làm nói với ông chủ của em, khi ông chủ cần cặp ngựa để thắng cái xe, để đi một lèo vượt Trường Sơn, cứu con bịnh thập tử nhất sinh Miền Nam, và trong cơn mệt mỏi giận dữ tìm hoài không ra cặp ngựa, lối xóm cũng chẳng ai cho mượn, bèn đạp cái cánh cửa chuồng lợn đánh rầm một cái, cửa mở tung, và con quỉ chuồng lợn xuất hiện, cùng cặp ngựa: -Ông chủ mà cũng không biết trong nhà của mình có gì! Dân Miền Bắc không hề nghĩ đến, chẳng bao giờ thắc mắc về một con quỉ nằm ở trong đáy sâu, trong xương, trong hồn, trong tủy họ, cho đến khi đánh cho Mỹ cút Ngụy nhào, thì nó mới nhe nanh múa vuốt xuất hiện, hà, hà, ăn cướp mà dám nói giải phóng hử, hử! * Viên y sĩ đá cánh cửa bật tung, và "giải thoát" (deliver: sinh nở, giải thoát) - trước sự sững sờ của ông - người chăn và hai con ngựa, từ nơi chuồng heo. Như sự xuất hiện của cái mũi, từ ổ bánh mì, trong chuyện của Gogol, sự xuất hiện của người chăn và hai con ngựa trong "Y sĩ Đồng quê" đã được miêu tả hầu như là một cơn đẻ (as a birth): người chăn ngựa bò ra "bằng bốn chân", hai con ngựa, "con nọ tiếp con kia, bốn chân lẳn vào mình..." Cắn vào má Rose là hành động đầu tiên của người chăn ngựa, vì vậy mà viên y sĩ gọi anh là "đồ súc vật". Tính dâm tà của anh, và vụ xâm phạm cô gái thực sự mang tính thú vật. Viên y sĩ có thể nghe "cánh cửa nhà tôi long ra từng mảnh dưới những cú đập của tên chăn ngựa". Cùng lúc, tên chăn ngựa đóng vai quen thuộc của quỉ dữ, trong chuyện dân gian, đề nghị một chuyện trao đổi ma quái. Tên giữ ngựa/con quỉ như từ dưng không trồi lên, dụ khị (offering) thân chủ của nó: mày muốn được cái đó hả, thì đây này; nhưng, cái mà con quỉ lấy đi còn quí giá, còn ý nghĩa hơn nhiều. Viên y sĩ nói: ta sẽ không đổi chuyến đi với cái giá cô gái. Nhưng một khi ông chấp nhận đôi ngựa, "định mệnh đã an bài"! Tchekhov và Kafka Bạn cũng có thể hình dung ra con quỉ, là anh láng giềng độc địa, mày cần cặp ngựa ư, OK, và cung cấp cho anh bộ đội Cụ Hồ đủ thứ trên đời, luôn cả mấy sợi lông chim mà cũng ‘made in China’, và đến khi làm thịt được thằng em Nam Bộ, mới hà, hà, nào đảo đâu, núi đâu, gái đâu, Bô Xịt đâu…. ? Na Anh

cũng nhớ ông bố đã từng

quất cho anh hai chục lần rồi xát dầu cù là con hổ lên vết thương. Và

anh

biết được một điều là bố anh đã từng chứng kiến vụ tàn sát Mỹ Lai, khi

ông mới

14 tuổi, và may mắn sống sót, nhờ nằm bên dưới một cái hố, trên là

những xác dân làng,

trong có mẹ ruột của ông, tức bà nội của anh, trên một chục mạng bị

lính Mỹ xả

súng máy, sát hại. THE

BOAT is an engaging and

free-wheeling collection of seven short stories by first-timer Nam Le,

organized in a cleverly self-referential package. In the pivotal first

story,

"Love and Honor and Pity and Pride and Compassion and Sacrifice" (a

title drawn from William Faulkner's Nobel Prize acceptance speech in

1950), a

young Vietnamese American lawyer-turned-aspiring author named The poet's, the

writer's, duty is to write about these things. It is his privilege to

help man

endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor

and hope

and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the

glory of

his past. The poet's voice need not merely be the record of man, it can

be one

of the props, the pillars to help him endure and prevail. Gặp Hà Nội 1

phát là mê liền. Nguồn |