|

Toàn những chi tiết thú vị. Một trang TV

cũ

J'ai subi un

deuxième choc littéraire en 1957, quand « L'étranger », d'Albert Camus,

a été

traduit en hongrois. Pour moi, c'était une révélation décisive qui m'a

radicalement influencé dans mes choix.. [Tôi bị cú sốc

văn chương thứ nhì khi Kẻ Xa Lạ

được dịch qua tiếng Hung, vào năm 1957. Đây

đúng là một cú mặc khải ảnh hưởng tới sự chọn lựa của tôi]

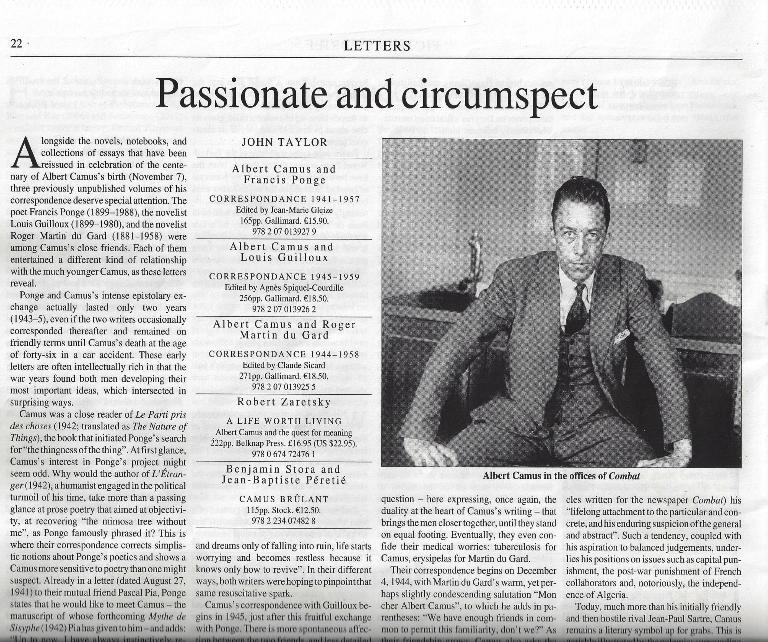

by Robert Zaretsky In honor of

the French novelist, essayist, and philosopher November

7th, 2013 Robert Zaretsky, has published a new book, A Life Worth Living: Albert Camus and the Quest for Meaning, published by Harvard University Press in honor of the centenary of Camus's birth, today. Zaretsky also penned the following in honor of the French novelist, essayist, and philosopher. Robert

Zaretsky đã chơi 1 cuốn sách mới về Camus, “Một đời đáng sống: cuộc

truy tìm cái

nghĩa”, nhà xb ĐH Harvard Press. Bữa nay, 7 tháng 11, 2013, đúng SN

Camus 100 năm

trước đây, ông bèn đi một đường vinh danh Camus, người Tây, tiểu thuyết

gia, tiểu

luận gia và triết gia.

That boy,

the French Algerian writer and moralist Albert Camus, was born 100

years ago

today. In his last and unfinished novel, "The First Man", Camus

recreates not

just this scene, but one where he visits the grave of the father he

never knew,

killed in the Battle of the Marne when Camus was an infant. As Camus’s

fictional alter ego, Jacques Cormery, stares at the tombstone, all

around him,

“in the vast field of the dead, silence reigned.” Only when Cormery

hears a

noise made by another visitor does he see, as if for the first time,

the dates

under his father’s name: “1885–1914.” His silence deepens with the

realization

that the “man buried under that slab, who had been his father, was

younger than

he.” To gaze at

Camus’ own modest gravestone in the southern French village of

Lourmarin, the

inscription “1913–1960” delivers a similar shock. When he left us,

Camus was

younger than many of us are now; what his father left his son, his son

has left

us: a profound silence that surges through his remarkable writings and

life. This silence

is neither poetic nor mere rhetoric: it was a brute fact of Camus’s

life. Not

just the absent father, but also the present, yet mute mother. An

illiterate

cleaning woman, Catherine Camus spoke with difficulty — a handicap

perhaps due

to the shock of her husband’s death. The young Camus would sometimes

find his

mother “huddled in a chair, gazing in front of her” in the small

apartment they

shared with his illiterate grandmother and partly mute uncle in a

working class

neighborhood of Algiers. Her muteness, he recalled, seemed

“irredeemably

desolate.” The silent

mother haunts Camus’s writings: it is the dark matter toward which

everything

else is pulled. In "The Stranger", it is the death of Meursault’s

mother that

begins the unmaking of his life; it is the mostly wordless presence of

Dr.

Rieux’s mother in "The Plague" that prevents the unmaking of a world

swept by

disease. Shortly before his death, Camus described his literary goal:

to write

a book about “the admirable silence of a mother and one man’s effort to

rediscover a justice or a love to match this silence.” What did

Camus mean? That the depths of maternal silence can never be fully

plumbed by a

son? Camus always struggled with the fact that his life’s work was for

a woman

who could neither read nor talk. What he wanted most in the world was

for his

mother “to read everything that was his life and his being, that was

impossible. His love […] would forever be speechless.” This was no

less the case with his other love, Algeria. By the late 1950s, the

blood-dimmed

tide of revolution and repression had spread across Camus’s native

country.

Ever since the 1930s, when as a young journalist he wrote fiery

articles

denouncing France’s treatment of the Arab population, Camus had always

fought

for a French Algeria where the ideals of 1789 would be applied to

everyone,

Arab and French alike. The two peoples, he insisted, were condemned to

live

together. Yet it soon

became clear that two peoples were instead condemned to kill one

another. As

acts of terrorism and counter-terrorism ravaged his country, Camus flew

to

Algiers to call for a civilian truce. As he spoke inside a large hall,

a vast

crowd of fellow French Algerians surged towards the building, shouting

for his

death. Camus insisted on finishing the speech, but then had to be

rushed out of

the building by friends serving as bodyguards. When he

returned to France, he decided he would no longer speak or write about

the

conflict. To what end? Given the tragic character of the conflict,

silence was

all he had left. He did act privately, though, intervening dozens of

times with

the French authorities, pleading that they commute death sentences

dealt to

Arab prisoners. His appeals were mostly ignored, but the integrity of

his

efforts will never fade. During his

visit to Stockholm for the Nobel ceremony, however, circumstances did

force him

to speak. At a public forum, an Arab student began to assail him for

his

silence. Increasingly distraught and angry, Camus finally managed to

stop the

tirade, declaring: “I have always condemned terror. But I must also

condemn

terrorism that strikes blindly in the streets of Algiers, and which

might

strike my mother and family. People are now planting bombs in the

tramways of

Algiers. My mother might be on one of those tramways. If that is

justice, then

I prefer my mother.” The press

mangled the last line — “I believe in justice, but I’ll defend my

mother before

justice,” Le Monde

misreported — but both versions underscored Camus’s dilemma.

Words had proved at best useless, at worst complicit in the widening

gyre of

violence. As with his mother, who made him silently feel an “immense

pity

spread out around him,” so too did Camus feel for the Algerian student.

“I feel

closer to him,” he confessed, “than to many French people who speak

about

Algeria without knowing it. He knew what he was talking about, and his

face

reflected not hatred but despair and unhappiness. I share that

unhappiness.” In his Nobel

speech, Camus had said that silence, at certain moments, “takes on a

terrifying

sense.” Algeria was, for Camus, one of those moments. Words were worse

than

useless: incapable of stemming the catastrophe, they instead obscured

its

dimensions and meaning. Silence followed from his recognition that the

humiliated were on both sides in this conflict: the great majority of

French

Algerians — the working poor like his own family — as well as Arabs.

The truths

at play in Algeria were, for Camus, incompatible. On the

centenary of Camus’s birth, we are left with this truth, left with this

silence, left to us by an artist who died too soon.

|