|

|

|

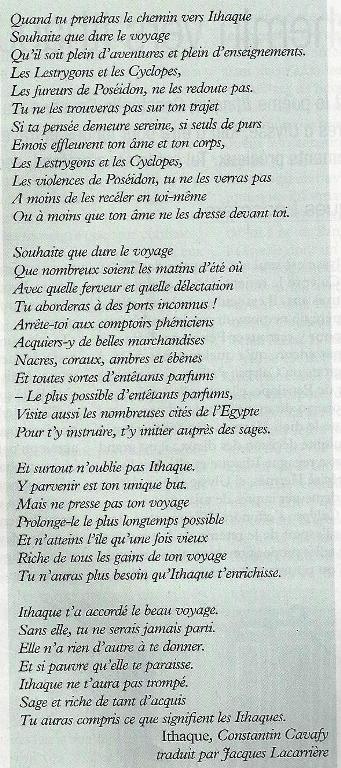

Tính dịch

bài thơ “Về Xề Gòn gặp Cớm VC làm quái gì” [Ithaca]

của nhà thơ Cavafis, cùng bài viết thần sầu của Vargas Llosa, về nhà

thơ

"ghê" này, nay vớ được cuốn thơ trên cũng OK lắm.

Bernières là

tác giả “Captain Corelli's Mandolin”, rất nổi tiếng, đã chuyển thể

thành phim

và cái cuốn khác nữa.

THE

REGRET OF

AN OLD MAN

I knew you

before, when we were young,

You a temple maid and I an idle man.

I saw you

pass in white, a circlet on your head,

And in your hands the blood-filled golden bowl.

I do confess I loved the slender grace

That still

you have today.

I caught

your eye and smiled. Then,

When all were glad or sick with wine

I took you

to a rock and there I tried to take you.

You refused and ran.

I am glad we

meet again. I doubt if you remember.

Such a long time. I was born a fool. I have always been

sorry.

You were

young and lovely. I was an idle man.

Nỗi ân hận của

1 anh già

Ta biết em từ

xưa, khi em còn bé tí

Và ta, 1 thằng

thanh niên đại lãn, biếng nhác

Ta nhìn thấy

em, khi đó là 1 cô tớ gái quanh quẩn nơi quán, miếu, hay chùa làng

Em đi qua đường,

đầu chit tấm băng đô

Bưng tô vàng

đựng huyết

Ta phải thú

thiệt, ta cảm em liền

Bởi cái mảnh

khảnh duyên dáng của em

Mà bi giờ vưỡn

còn

Mắt ta bắt

được ánh mắt của em và mỉm cười

Cả hai đều

vui, và bịnh vì bia bọt

Ta lôi em vô

chỗ có hòn đá bự, và tính làm thịt em

Em đá cho ta

1 phát, và bỏ chạy!

Hà, hà!

Ta rất mừng

vì gặp lại em. Ta đoán là em chẳng còn nhớ chuyện nhơ bửn đó.

Lâu quá rồi,

làm sao nhớ.

Ta sinh ra là

đã khùng rồi

Nhưng ta luôn

luôn cảm thấy ân hận

Em trẻ

quá, xinh quá,

Còn ta, 1 thằng

thanh niên lười biếng.

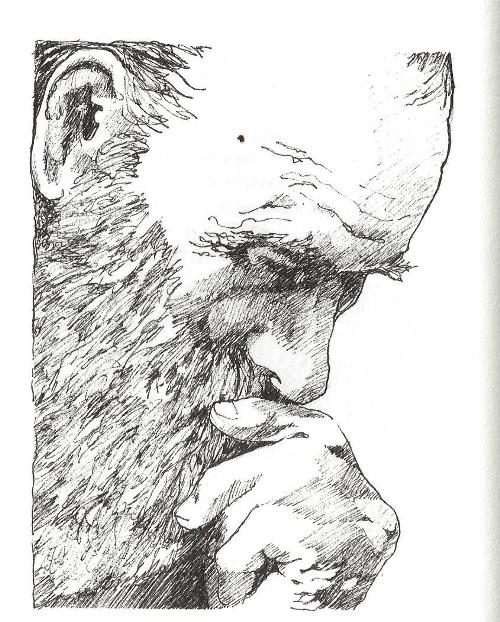

Note: Bức

hình y chang bức hình bìa cuốn thơ bộ lạc Cờ Lăng làm quà cho Cà, sau

khi chàng

thổi Ông Số 2 một chùm bài!

Bài thơ cũng…. y chang!

Hà, hà!

Lại nhớ những

buổi ngồi đợi Viên Linh, lãnh tí tiền còm, tại văn phòng Thời Tập.

Thằng đói cơm

đen. Thằng đói gái

Cũng y

chang!

VL bảnh thật.

Thơ thường đếch có nhuận bút.

Nhưng với ai chứ với Cà, thì, ngoại lệ!

Ám ảnh

phố phường

Dầu có muốn

hay không, thì vẫn phải thừa nhận, Du Tử Lê là một tên tuổi. Tôi thích

đọc Du Tử

Lê, những bài thơ mang đậm nét đèn vàng phố thị hay hiu hắt tóc xanh.

Hầu như

trong giới viết lách ở Sài Gòn, ít nhiều đều thuộc vài câu thơ của Du

Tử Lê. Thế

nên, khi nghe nhà văn, nhà báo Đoàn Thạch Hãn buột miệng nói: “Tôi với

Lê thân

lắm”, thì tôi vội vã gửi lời nhờ: “Khi nào chú Lê có dịp về lại Việt

Nam, chú

cho con gặp với”.

Hạnh ngộ, chỉ có

bấy nhiêu.

Dầu có muốn

hay không thì vẫn phải thừa nhận…

Đúng là chơi với… cớm, cớm

liếm mặt!

“Tôi với Lê thân

lắm”: Câu này phải để đao phủ HPNT nói mới phải, bởi vì bạn ta đã từng

tự động

gõ cửa.. Trùm Địa Ngục Mậu Thân!

Người Xề

Gòn

The Alexandrian

Poetry, for

Cavafy, like pleasure and beauty, could not be brought publicly to.

light, nor

were such things within everyone's reach: they were available only to

those

daring enough to seek them out and cultivate them as forbidden fruits,

in

dangerous territory.

*

Louis de Bernières. Tác giả Captain

Corelli's Mandolin,

1994, tiểu thuyết. (2)

Trên số Ðiểm Sách Văn Học Á Châu, Asia Literary Review Mùa Thu 2010, đặc

biệt về Khờ Me Ðỏ, có hai bài thơ thật tuyệt của ông, viết giùm cho

GNV, gửi

BHD!

Poetry

Louis de Bernieres

Two poems written after

arriving in Hong Kong on the author's

first visit; March 2010

The Man Who

Travelled the World

He travelled the world,

restless as rain.

There was no continent unexplored,

Scarcely a city unworthy of days, a night, a week.

In all these places he searched for her face

In the streets, in the parks, in the lanes,

Always pausing to look, listening out

For the voice he'd never heard yet, yet

Always knew he would know.

So many lovers, so many

encounters,

So many years, so many lands.

Now he sits by the window, a cat in his lap,

An ancient man far off from the

place of his birth.

And inside that loosening frame of bones

Beats the same heart as the heart that

Beat in the young boy who knew she was there,

And set off to travel the world.

He thinks of the children he

never had,

The ordinary things foregone,

The perverseness of such an exhausting,

Such an impossible search;

A whole life squandered on dreams.

It begins to rain; he puts on his glasses

Looks through the window, watches the girls

Step by, avoiding the puddles, protecting

Their hair with their magazines.

He fondles the ears of the cat,

This ancient man far off from the place of his birth,

Still looking, still in fief to the same unsatisfied heart

As the heart that beat in the young boy

Who knew she was there, and

Set off to travel the world.

Put Out the Light

Close the shutters,

Put out the light,

Place one candle on the shelf

See, we are young again;

Our malformations, all life's

Etchings in our flesh are gone,

Are evened out, engoldened,

Softened by shadow.

Your hair smells sweet, your

Head in the crook of my arm, your

Hand on my chest.

We will lie like this til the candle dies,

And then, in the dark, lie face to face.

They'll glitter like moonlight on water,

Our old, experienced eyes.

AT THE

SORBONNE

He walked

these streets the first time

(He was

young and handsome then)

With a woman

he betrayed,

And the

streets remind him of her golden hair,

Her easy

ways, the black stone set in the silver ring.

He bought

Montaigne, white sausage.

It was

Christmas. They'd bought a duck

And cooked

it badly.

These were

the times when

Intellectuals

gathered in cafés,

Avid for

seduction,

Talked of

revolution,

Ranged in

the Latin Quarter, smoked for the sake of style.

You might

perhaps run into Roland, Jean-Paul and Simone.

Georges was

writing songs.

It was after

Albert crashed and died.

There was no

hot water, this was Paris;

The sewage

breathed from the grates;

The women

went out with their poodles.

The coffee

was perfect, the cafes warm:

The Café

Rodin

The Café

Louvre

The Café Jeu

de Paumes.

They kissed

in the dark, oblivious;

They kissed

in the light, in public, mischievous.

They made

love and made love and made love;

Youth

eternal, the hunger immense,

The years

ahead so long,

Faith and

hope unquenched.

When they

came home the pipes were iced;

The cats

brought gifts of rabbits,

Voles and

mice and woodcock.

They boiled

a kettle, melted the ice,

Lit the

fire, went out and ate,

Came back to

shivering sheets.

Later,

betrayal. It all came later;

Her

penitential tears, her hair falling about her eyes,

Her features

crooked with remorse, her musician's hands

Trembling on

his shoulders.

He was correct

and stiff, but

Found it

easy to forgive.

He was

grateful, after a fashion;

It gave him

his excuse.

When he

considers the many, the substitutes

Who left,

reciting their lists of lovers;

When he

walks these streets,

Scarcely

believing the slippage,

He then

remembers the gold-haired girl,

With her

easy ways, her musician's hands,

Her

penitential tears, her kisses.

Louis de

Bernières: Imagining Alexandria

Ithaca

Thơ, với

Cavafy, như lạc thú và cái đẹp, đám mắt trắng dã - quần chúng, đám

đông, tập thể…- không thưởng thức được,

những

thứ đó không

ở trong tầm tay của mọi người: chúng chỉ có đó, cho những con người đủ

“dám” để mà khui, móc chúng ra, và trồng trọt,

săn sóc chúng như là những trái cấm, trong 1 khoảnh đất nguy hiểm.

Poetry, for

Cavafy, like pleasure and beauty, could not be brought publicly to

light, nor were

such

things within everyone‘s reach: they were available only to those

daring enough

to seek them out and cultivate them as forbidden fruits, in dangerous

territory.

Vargas

Llosa: The Alexandrian

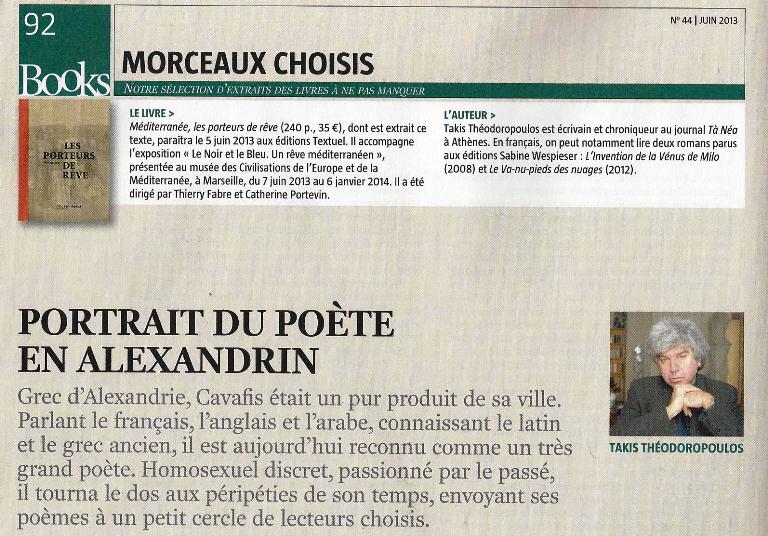

Bài viết về

Cavafy của Vargas Llosa, Gấu đọc cũng lâu rồi, cũng tính giới thiệu với

độc giả

TV, nhưng lại quên đi. Mới đây, đọc bài trên tờ Books về Cavafy, cũng

thú lắm:

Những người khuân vác mộng. Chắc là phải đi 1 đường về ông thi

sĩ "ghê"

này thôi.

Ithaca

ULYSSE PASSE

DEVANT ITHAQUE

Qu'est-ce

que ces rochers, ce sable? C'est Ithaque,

Tu sais

qu'il y a la l'abeille et l'olivier

Et l'épouse

fidèle et le vieux chien,

Mais vois,

l'eau brille noire sous ta proue.

Non, ne

regarde plus cette rive! Ce n'est

Que ton

pauvre royaume. Tu ne vas pas

Tendre ta

main à l'homme que tu es,

Toi qui n'as

plus chagrin ni esperance.

Passe, décois.

Qu'elle fuie à ta gauche! Voici

Que se

creuse pour toi cette autre mer,

La mémoire

qui hante qui veut mourir.

Va ! Garde désorrnais

le cap sur l'autre

Rive basse,

là-bas! Où, dans l'écume,

Joue encore

l'enfant que tu fus ici.

Yves

Bonnefoy

ULYSSES PASSES ITHACA

What's this pile of rocks

and sand? Ithaca ...

You know you'll find the bees, the ancient dog,

The olive tree, the faithful wife. But look:

The water glitters, black under your prow.

No, don't waste another

glance: this coast

Is just your threadbare kingdom. You won't

Shake the hand of the man you are now-

You who've lost all sorrow, and all hope.

Sail on, disappoint them.

Let the island slip by,

Off to port. For you, this other sea unrolls:

Memory haunts the man who wants to die

Speed ahead. From this day

on, set your course

For that low, huddled shore. There, in the foam,

Plays the child that you once were, here.

Ulysse đi ngang Xề Gòn

Cái đống kè đá, cát kiết

kia là cái gì hử? Xề Gòn đó.

Mi biết mà, ở đó có đàn ong, có con chó già

Có cây ô liu và bà vợ trung thành

Nhưng coi kìa, dòng nước long lanh, đen thui, dưới mũi thuyền

Không, đừng nhìn bờ sông

nữa

Thì đúng vưỡn chỉ là cái vương quốc khốn khổ của mi ngày nào

Mi sẽ chẳng thể bắt tay cái kẻ là mi bây giờ

Mi, kẻ đếch còn đau buồn, hy vọng

Dong buồm tếch thôi, kệ

cha Xề Gòn và

những con người của nó đang từ từ trôi xa ở phía mạn trái thuyền

Một biển khác, một Xề Gòn khác đang chờ mi

Hồi ức săn đuổi kẻ nào muốn chết

Tăng tốc thuyền, kể từ

ngày hôm nay

Hướng về một Xề Gòn khác, kè đá khác

Hãy nô đùa với đứa trẻ, là mi, ngày nảo ngày nào

Cái ngày mà mi còn Xề Gòn của mi

Bài thơ, nguyên

tác tiếng Tẩy. Nay coi lại, post thêm cho đủ bộ.

Bèn [sẽ] đi thêm, Bông Hồng Độc Nhất, La Seule Rose, The

Only

Rose, và ba kỷ niệm của Yves Bonnefoy, về Borges, trong có nhắc tới

1

truyện ngắn thần sầu của Hawthorne. Quả đúng là thần sầu. Làm Gấu nhớ

tới

cái truyện ngắn về người khách lạ, mà Gấu đọc cùng với bà cụ TTT, những

ngày còn đi học, The

Ambitious Guest.

*

Thơ, với

Cavafy, như lạc thú và cái đẹp, đám mắt trắng dã - quần chúng, đám

dông, tập thể…- không thưởng thức được,

những

thứ đó không

ở trong tầm tay của mọi người: chúng chỉ có đó cho những con người đủ “dám” để mà khui, móc chúng ra, và trồng trọt,

săn sóc chúng như là những trái cấm, trong 1 khoảnh đất nguy hiểm

Poetry, for

Cavafy, like pleasure and beauty, could not be brought public, nor were

such

things within everyone‘s reach: they were available only to those

daring enough

to seek them out and cultivate them as forbidden fruits, in dangerous

territory

Vargas

Llosa: The Alexandrian

Bài viết

về

Cavafy của Vargas Llosa, Gấu đọc cũng lâu rồi, cũng tính giới thiệu với

độc giả

TV, nhưng lại quên đi. Mới đây, đọc bài trên tờ Books về Cavafy, cũng

thú lắm:

Những người khuân vác mộng. Chắc là phải đi 1đường về ông thi sĩ "ghê"

này thôi.

Ithaca

When you

start on your way to Ithaca,

pray that

the journey be long,

rich in

adventure, rich in discovery.

Do not fear

the Cyclops, the Laestrygonians

or the anger

of Poseidon. You'll not encounter them

on your way

if your thoughts remain high,

if a rare

emotion possesses you body and soul.

You will not

encounter the Cyclops,

the

Laestrygonians or savage Poseidon

if you do

not carry them in your own soul,

if your soul

does not set them before you.

Pray that

the journey be a long one,

that there

be countless summer mornings

when, with

what pleasure, what joy,

you drift

into harbours never before seen;

that you

make port in Phoenician markets

and purchase

their lovely goods:

coral and

mother of pearl, ebony and amber,

and every

kind of delightful perfume.

Acquire all

the voluptuous perfumes that you can,

then sail to

Egypt's many towns

to learn and

learn from their scholars.

Always keep

Ithaca fixed in your mind.

Arrival

there is your destination.

Yet do not

hurry the journey at all:

better that

it lasts for many years

and you

arrive an old man on the island,

rich from

all that you have gained on the way,

not counting

on Ithaca for riches.

For Ithaca

gave you the splendid voyage:

without her

you would never have embarked.

She has

nothing more to give you now.

And though

you find her poor, she has not misled you;

you having

grown so wise, so experienced from your travels,

by then you

will have learned what Ithacas mean.

C. P.

CAVAFY: SELECTED POEMS

ULYSSES PASSES ITHACA

What's this pile of rocks

and sand? Ithaca ...

You know you'll find the bees, the ancient dog,

The olive tree, the faithful wife. But look:

The water glitters, black under your prow.

No, don't waste another

glance: this coast

Is just your threadbare kingdom. You won't

Shake the hand of the man you are now-

You who've lost all sorrow, and all hope.

Sail on, disappoint them.

Let the island slip by,

Off to port. For you, this other sea unrolls:

Memory haunts the man who wants to die

Speed ahead. From this day

on, set your course

For that low, huddled shore. There, in the foam,

Plays the child that you once were, here.

Yves Bonnefoy

Ulysse đi ngang Xề Gòn

Cái đống kè đá, cát kiết

kia là cái gì hử? Xề Gòn đó.

Mi biết mà, ở đó có đàn ong, có con chó già

Có cây ô liu và bà vợ trung thành

Nhưng coi kìa, dòng nước long lanh, đen thui, dưới mũi thuyền

Không, đừng nhìn bờ sông

nữa

Thì đúng vưỡn chỉ là cái vương quốc khốn khổ của mi ngày nào

Mi sẽ chẳng thể bắt tay cái kẻ là mi bây giờ

Mi, kẻ đếch còn đau buồn, hy vọng

Dong buồm tếch thôi, kệ

cha Xề Gòn và

những con người của nó đang từ từ trôi xa ở phía mạn trái thuyền

Một biển khác, một Xề Gòn khác đang chờ mi

Hồi ức săn đuổi kẻ nào muốn chết

Tăng tốc thuyền, kể từ

ngày hôm nay

Hướng về một Xề Gòn khác, kè đá khác

Hãy nô đùa với đứa trẻ, là mi, ngày nảo ngày nào

Cái ngày mà mi còn Xề Gòn của mi

Il ritorno d'Ulisse

Returning from a lengthy

trip

he was astonished to find

he had strayed to a country

not his place of origin

For all his encounters in

scattered spots

with the black paper hearts of men

shot by the arquebuse

his bow-and-arrow story

did not happen

Then there was Penelope's

Castilian grandmother

blocking his entry at the garden gate

wordless and busy with embroidery

Sure, the grandchildren

are smiling in the background

apparently better disposed

towards foreigners

Their furtive hopes

still almost too small

for the naked eye

(But the idea is good

and the noise far away

even the building)

Sebald: Qua

sông & Nước

Note: Bài thơ này làm nhớ

một, hai bài thơ trong Thơ Ở Đâu Xa, tả cảnh anh tù, nhà thơ,

sĩ quan VNCH, gốc Bắc Kít, về quê Bắc Kít ngày nào, và, tất

nhiên, còn làm nhớ bài thơ của TTY, Ta Về.

Ta Về

Trở về sau 1 chuyến dài

dong chơi địa ngục

Hắn kinh ngạc khi thấy mình lạc vô 1 xứ sở

Đếch phải nơi hắn sinh ra

Trong tất cả những cú gặp

gỡ ở những điểm này điểm nọ rải rác, tản mạn

Với những trái tim giấy đen của những người bị bắn bởi cây súng mút kơ

tông

Thì giai thoại, kéo cây cung thần sầu, bắn mũi tên tuyệt cú mèo, đếch

xẩy ra.

Và rồi thì có bà ngoại Tây

Bán Nhà của Penelope

Bà chặn đường dẫn vô vườn

Đếch nói 1 tiếng, và tỏ ra bận rộn với cái trò thêu hoa văn khăn tay

Gửi người lính trận vượt Trường Sơn kíu nước,

Này khăn tay này, này thơ này,

Đường ra trận mùa này đẹp nắm!

Hà, hà!

Tất nhiên rồi, chắc chắn

có lũ con nít

– không phải nhếch nhác kéo nhau coi tù Ngụy qua thôn nghèo –

chơi ở vườn sau, chúng có vẻ rất tự nhiên, mỉm cười với khách lạ

Những hy vọng ẩn giấu của

chúng

vẫn hầu như quá nhỏ nhoi,

với con mắt trần trụi

(Nhưng ý

nghĩ thì tốt

Và tiếng động thì xa

mặc dù tòa nhà) (2)

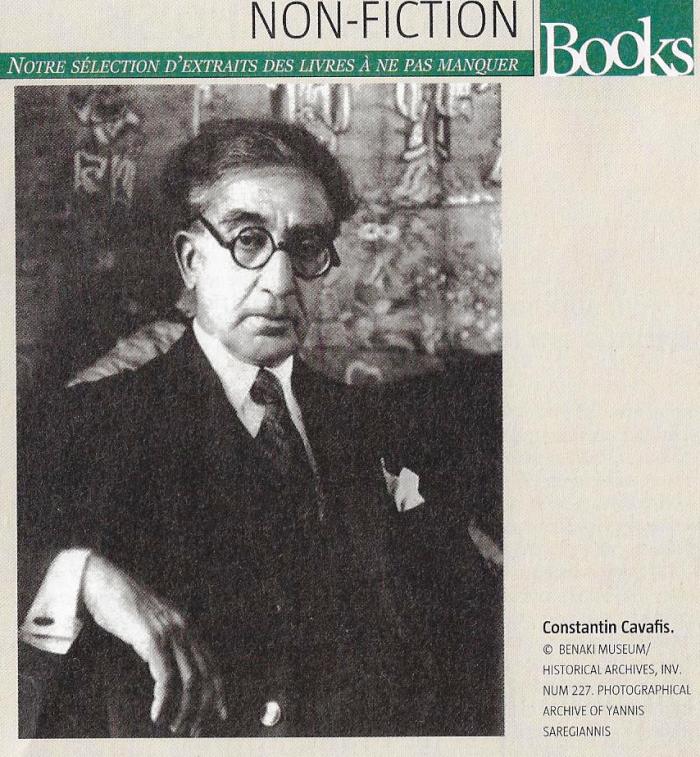

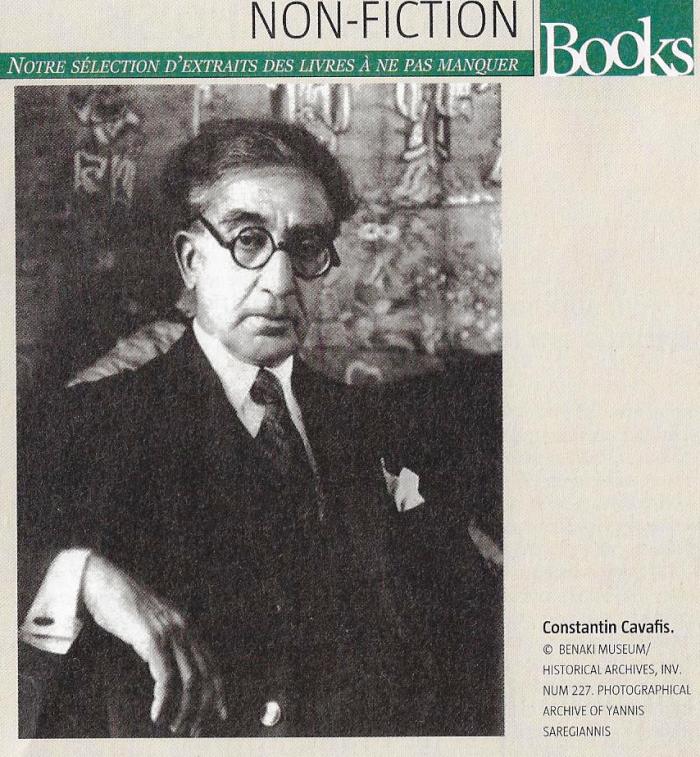

The Alexandrian

The apartment in

Alexandria where the poet Constantine Cavafy (1863-1933) lived the last

years of his life is in a run-down building in the center of the city,

on a street that was called Lepsius when the neighborhood was inhabited

by Greeks and Italians and is now called Charrn-el-Sheik. Some Greeks

are still in the area, to judge by a few signs in Hellenic script, but

what predominates everywhere is Arabic. The neighborhood has

deteriorated and is full of cramped alleyways, houses in ruins, and

potholed paths, and-a typical sign of poor neighborhoods in Egypt-the

residents have turned the roofs into stinking garbage dumps. But the

beautiful little rthodox church that the faithful attended in Cavafy's

time is still there, and the graceful mosque, too, and the hospital,

although the brothel that operated on the ground floor of his building

has disappeared.

The apartment is a small museum in the care of the

Greek consulate, and it must not get many visitors, to judge by the

sleepy boy who opened the door for us and stared at us as if we were

Martians. Cavafy is practically unknown in the city immortalized by his

poems, which are, along with the celebrated library burned to the

ground in antiquity and Cleopatra's love affairs, the best thing that

has happened to it since it was founded by Alexander the Great in 331

B.C. No streets are named after him and no statues memorialize him. Or

if they exist, they don't appear in the guidebooks and no one knows

where to find them. The apartment is dark, with high ceilings and

gloomy hallways, and it is furnished as circumspectly as it must have

been when Cavafy set up house here with his brother Peter in 1907. The

latter lived with him for just a year, then left for Paris. From that

moment on, Constantine lived here alone; and, it seems, with

unfaltering sobriety, so long as he remained within his apartment's

thick walls.

This is one of the settings for the less interesting

of Cavafy's lives, one that leaves no impression on his poetry and is

difficult for us to imagine when we read about it: the life of an

immaculately attired and unassuming bourgeois who was a broker on the

cotton exchange and worked for thirty years as a model bureaucrat in

the Irrigation Office of the Ministry of Public Works, where, as a

result of his punctuality and efficiency, he rose to the rank of deputy

manager. The photographs on the walls pay testimony to this civic

prototype: the thick tortoiseshell spectacles, the stiff collars, the

tightly knotted tie, the little handkerchief in the top pocket of the

jacket, the vest with its watch chain, and the cuff links in the white

shirt cuffs. Clean-shaven and well groomed, he gazes seriously at the

camera, like the very incarnation of the man without qualities. This is

the same Cavafy who died of cancer of the larynx and is buried in the

Greek Orthodox cemetery of Alexandria, among ostentatious mausoleums,

in a small rectangle marked by marble tombstones, which he shares with

the bones of two or three relatives.

In the small museum there is not a single one of the

famous broadsheets on which he published his first poems and which, in

insignificant printings-of thirty or forty copies-s-he parsimoniously

distributed to a few chosen readers. Nor are there any of the

pamphlets-there were fifty copies of the first, seventy of the

second-in which on two occasions he gathered a handful of poems, his

only works published in anything approaching book form in his lifetime.

The secrecy in which this august poet shrouded the writing of poetry

didn't only have to do with his homosexuality, a shameful failing in a

public functionary and petit bourgeois of that time and place who in

his poems expounded with such surprising freedom on his sexual

predilections; it had also, and perhaps especially, to do with his

fascination with the clandestine, the underground, the marginal and maudit

life that he slipped into from time to time and that he lauded with

unparalleled elegance. Poetry, for Cavafy, like pleasure and beauty,

could not be brought publicly to. light, nor were such things within

everyone's reach: they were available only to those daring enough to

seek them out and cultivate them as forbidden fruits, in dangerous

territory.

Of this Cavafy there is only a fleeting trace in the

museum, in a few undated little drawings scrawled in a school notebook,

the pages of which have been pulled out and stuck up on the walls

without any kind of protection: boys, or maybe the same boy in

different positions, showing their Apollonian silhouettes and erect

phalluses. This Cavafy I can imagine very well, and have imagined ever

since I read him for the first time in the translation of his poems by

Marguerite Yourcenar: the sensual and decadent Cavafy, whom E. M.

Forster discreetly hinted at in his 1926 essay and who became a mythic

figure in Lawrence Durrell's Alexandria Quartet. Here, in his

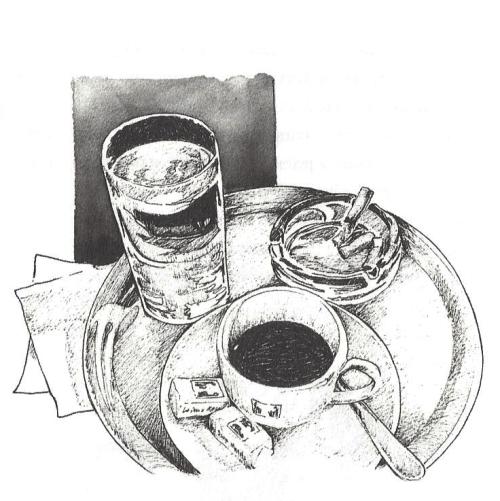

city, the cafés and tavernas of his poems are still thronged, and, as

in the poems, there are almost no women or heterosexual couples, I

don't know this for a fact, but I am sure that staged in them still,

amid the crowds of men-the air dense with the smell of Turkish coffee

and the clouds of smoke expelled by showy hookah smokers-are ardent

meetings, first encounters, and the monetary exchanges that precede the

fevered couplings of lovers of convenience in cheap rooms, their

sordidness and filth setting off the allure of exquisite bodies. I'd

even venture to say that I've witnessed it, on the terraces of The

Corniche or in the smoky hovels that surround the textile market: a

gentleman with a small sniffing nose, eager lips, and lustful little

eyes, at nightfall in the warm glow of the first stars and the sea

breeze, spying on the strapping young men who stroll with their

buttocks cocked, in search of clients.

Unlike the men-or, perhaps more accurately,

adolescents who love each other with serenity and ease in Cavafy's

poems, and enjoy sexual pleasure with the clear conscience of pagan

gods, Cavafy surely found these loves extremely difficult and

troubling, suffused at times with terror and always with frustrated

hopes. The astounding thing about his erotic poetry is that these

episodes-which must have been few and experienced under the terrible

strain of one who always kept up the appearance of respectability in

his public life and evaded scandal in any way he could-are transformed

into a kind of utopia: a supreme way of living and relishing life, of

escaping the bounds of the human condition and achieving a superior

form of existence, of attaining a kind of secular spiritual state. In

this state, through the pleasure of the senses and perceptions and the

appreciation of physical beauty, a human being ascends, like the

mystics in their divine trances, to the height of the gods, becoming a

god himself. Cavafy's erotic poems burn with an unbridled sexuality,

but despite that and their romantic trappings of decadence and

perdition, they are curiously cold, maintaining the rational distance

of an intelligence that governs the outpouring of passion and the

feasting of the instincts. At the same time that he represents this

ardor in verse, he observes it, studies it, and, with form as his tool,

perfects and eternalizes it.

His themes and his sexual inclinations are

infiltrated with nineteenth-century romanticism-excess and

transgression, aristocratic individualism-but at the moment he takes up

his pen and sits down to write, a classicist surges from the depths of

his being and seizes the reins of his spirit, obsessed with harmony of

form and clarity of expression, a poet convinced that deft

craftsmanship, clarity, discipline, and the proper use of memory are

preferable to improvisation and disorderly inspiration in reaching

absolute artistic perfection. He achieved that perfection: as a result,

his poetry is capable of resisting the test of translation-a test that

almost always vanquishes the work of other poets-so that it makes our

blood run cold in all its different versions, astounding even those of

us who can't read it in the demotic Greek and the Greek of the diaspora

in which it was written. (By the way, the most beautiful translation

into Spanish I've read of Cavafy's work is that of twenty-five poems by

the Spaniard Joan Ferrate. It was published by Lumen in 1970, in a

handsome edition illustrated with photographs, and, unfortunately, so

far as I know, it hasn't been reissued.)

This is the third Cavafy of the indissoluble

trinity: the one outside time who, on the wings of fantasy and history,

lived simultaneously under the yoke of contemporary Britain and twenty

centuries in the past, in a Roman province of Levantine Greeks,

industrious Jews, and merchants from all over the world, or a few

hundred years later, when the paths of Christians and pagans crossed

and recrossed in a heterogeneous society where virtues and vices

proliferated and divine beings and humans were almost impossible to

tell apart. The Hellenic Cavafy, the Roman, the Byzantine, the Jew,

leaps from one century to the next, from one civilization to another,

with the ease and grace of a dancer, always maintaining the coherence

and continuity of his movements. His world is not erudite at all,

although traces of his characters, settings, battles, and courtly

intrigues may be picked up in history books. Erudition sets a glacial

barrier of facts, explications, and references between information and

reality, and Cavafy's world has the freshness and intensity of life

itself, not life as it is lived in nature, but the enriched and

deliberate life-achieved without giving lip living-of the work of art.

Alexandria is always present in his dazzling poems,

because it is there that the events they evoke take place, or because

it is from the city's perspective that the deeds of the Greeks, Romans,

and Christians are glimpsed or remembered or yearned for, or because

the poet who invents and declaims is from there and wouldn't have

wanted to be from anywhere else. He was a singular Alexandrian and a

man of the periphery, a Greek of the diaspora who did more for his

cultural homeland-for its language and ancient mythology-than any other

writer since classical times. But how can a poet so thoroughly of the

Middle East-so identified with the smells, tastes, myths, and past of

his country of exile, that cultural and geographic crossroads where

Asia and Africa meet and are absorbed into each other as so many other

Mediterranean civilizations, races, and religions have been absorbed

into it-be so easily assimilated into the history of modern European

Greek literature?

All of those civilizations left traces on the world

created by Cavafy, a poet who was able to make another, different world

of all that rich historical and cultural material, one that is revived

and renewed each time we read him. Modern-day Alexandrians don't read

his poetry, and the vast majority don't even know his name. But when we

come here, the most real and tangible Alexandria for those of us who

have read him is not the beautiful beach, or the curve of the seaside

promenade, not the wandering clouds, the yellow trams, or the

amphitheater built with granite brought from Aswan, or even the

archaeological marvels of the museum. It is Cavafy's Alexandria, the

city where sophists discuss and impart their doctrines, where

philosophers meditate on the lessons of Thermopylae and the symbolism

of Ulysses's voyage to Ithaca, where curious neighbors come out of

their houses to watch Cleopatra's children-Caesarion, Alexander, and

Ptolemy-on their way to the Gymnasium, where the streets reek of wine

and incense when Bacchus passes by with his entourage just after the

mournful funeral rites of a grammarian, where love is a thing between

men, and where suddenly panic swells, because a rumor has spread that

the barbarians will soon be at the gates.

Alexandria, February 2000

Vargas Llosa: The

language of passion

|

|