|

|

BBT Tribute

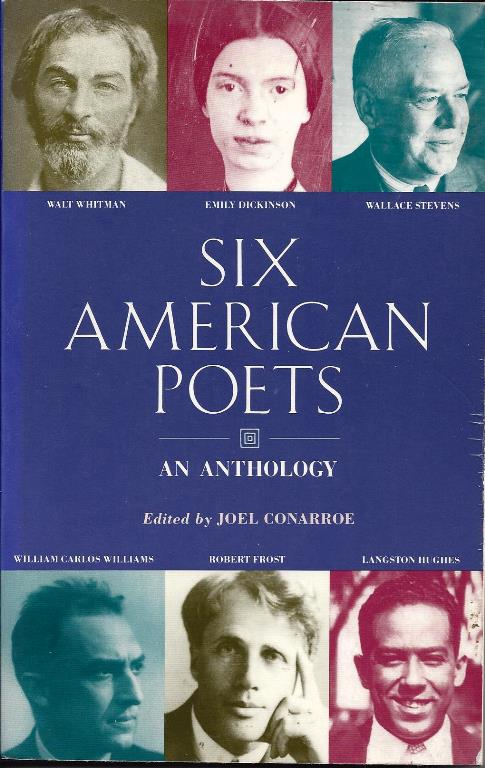

Nhớ, lần HC vừa nằm xuống, thay vì ai điếu, Gấu đi 1 đường cà khịa, và được K. nhắc nhở, chờ ít bữa không được sao? Chờ ít bữa, mất mẹ hứng, làm sao viết? Trường hợp nhà biếm gia số 1 Mít vừa mới mất, khi sinh thời ông đi, không chỉ 1, mà tới 2, ai điếu về NQT. Nhưng thay vì NQT/GCC thì là 1 vị sĩ quan cùng tên, bạn của ông. Có điều, ông cố tình nhập nhằng đến nỗi bạn bè của Gấu phải phôn, hỏi ông. Và chăng cũng chuyện nhỏ, chẳng đáng nhắc tới, và những gì cần nhắc, Gấu đã viết rồi, ngay từ khi ông còn sống. Tuy nhiên, nhân ông mất, và nhân đọc bài viết trên tờ Harper's về lần Steiner, thì cũng 1 biếm gia, được gặp cha đẻ ra bom nguyên tử, để xin việc làm, và xém 1 chút bị đá ra khỏi văn phòng, bèn post ra đây, thay cho lời ai điếu BBT, của TV. Vụ này, sự thực, Steiner đã kể ra rồi, trong lần trả lời phỏng vấn của tờ The Paris Review, trên TV có giới thiệu. [Reminiscence] DESTROYER OF WORDS From an interview with the philosopher George Steiner that was conducted in 2014 by Laure Adler, a journalist. The interview appears in A Long Saturday, which will be published in March by the University of Chicago Press. Steiner is the author of more than two dozen books. Translated from the French by Teresa Lavender Fagan. The Economist sent me across the Atlantic to cover the debate on American atomic power: was the United States going to share its nuclear knowledge with Europe? Under Eisenhower, the Americans decided they wouldn't. It wasn't a given; there was still hope that there would be true collaboration. So I went to Princeton, a wonderful, unreal little town, to interview]. Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb. He had a pathological hatred of journalists, but said, "I'll give you ten minutes." Oppenheimer had set our meeting for noon. He didn't come. So I had lunch with George Kennan, the diplomat of diplomats; Erwin Panofsky, the leading art historian at the time; and Harold Cherniss, the great Hellenist and Plato specialist. Afterward, while I was waiting for the taxi that was to pick me up a half hour later, Cherniss invited me to his office, and as we were talking, Oppenheimer came in and sat behind us. It was the ideal trap: if the people you're talking to can't see you, they feel paralyzed, and you become master of the situation. Oppenheimer was a genius at this sort of theatrical maneuvering. He was a man who inspired spine-chilling fear; it's quite difficult to describe. I once heard him say to a young physicist, "You are so young and you have already done so little!" After comments like that, you could only hang yourself. Cherniss was showing me a passage from Plato that he was editing, which included a lacuna; he was trying to fill it in. When Oppenheimer asked me what I would do with that passage, I began stammering. Then he added, ''A great text should have some empty space." I said to myself, "Hey, you've nothing to lose, your taxi will be here in fifteen minutes." And so I replied, "That's a pompous cliché. First, your statement is a quote from Mallarrné, Second, it's the type of paradox you can play with ad infinitum. But when you're trying to prepare an edition of Plato for the common mortal, it's better that the empty spaces be filled." Oppenheimer responded superbly: "No, in philosophy especially it is the implicit that stimulates argument." He was enjoying our exchange immensely, he whom no one ever dared to contradict. We had a real discussion on the subject. Then Oppenheimer's secretary ran in and announced, "Mr. Steiner's taxi is about to leave!" I was going on to Washington for my reporting assignment. At the door this extraordinary man asked me, as one might speak to a dog, "You're married?" "Yes." "You have children?" "No." "Great. That will make it easier to find lodging." That's how he invited me to the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, as the first young humanist. Note: Sự thực, đọc những người viết, thứ Bắc Kỳ di cư, như Kiều Phong, Thương Sinh, Công Tử Hà Đông, BBT... luôn cả Gấu trong đó, thì Gấu nhớ tới cái còm của O., 1 trong 2 vị được coi như "hộ pháp" cho TV ngay từ lúc mới có được ít lâu. Không có hai vị này, Tin Văn chắc là đầy lỗi, sạn, thì chỉ nhắc tới thứ vụn vặn đó, trước, cái còn lại, cái "hồn nhân hậu" của trang viết, chưa nói tới, để viết sau, nếu chưa chết. Trong cả 1 lũ viết như thế, đều có chung 1 văn phong, cực kỳ độc, đểu, mất dậy.... Bắc Kỳ xỏ lá ba que. Những người khác, trong đó, không nói, riêng Gấu, Gấu rất tởm, và cả 1 đời, cố tìm cách "wash" theo cái nghĩa mà Milosz đã viết ra rồi . To

At the end of his life, a poet thinks: I have plunged into so many of the obsessions and stupid ideas of my epoch! It would be necessary to put me in a bathtub and scrub me still all that dirt was washed away. And yet only because of that dirt could I be a poet of the twentieth century, and perhaps the Good Lord wanted it, so that I was of use to Him. Một nhà thơ của thế kỷ

20, cuối đời nhìn lại, thấy mình bẩn quá, bèn

chui vô bồn tắm, dùng xà bông thơm kỳ cọ,

cho văng tất cả những cái bẩn đi. Tởm Người ta đã nói

nhiều về những tội ác của chế độ cộng sản. Ít ai cho

biết, tôi đã tởm chế độ đó đến mức như thế nào.

Câu chuyện sau đây là của nhà văn, nhà

thơ lưu vong người Balan, Czeslaw Milosz, Nobel văn chương 1980, trong

tác phẩm Milosz's ABC's. Disgust Józef Czapski là

người kể cho tôi [Milosz] câu chuyện sau đây, xẩy

ra trong thời kỳ Cách Mạng Nga. Bất thình lình, ông tàn dư bèn đứng dậy, rút khẩu súng lục từ trong túi ra, và đưa ngay mõm súng vào trong mõm mình, và đoàng một phát. Hiển nhiên, mức tởm lợm

tràn quá ly. Chẳng nghi ngờ chi, ông ta là

một thứ người mảnh mai, được giáo dục, dậy dỗ, và trưởng

thành trong một môi trường mà một con người như thế

dư sức sống, và sống thật là đầy đủ cái phần đời của

mình mà Thượng Đế cho phép, nghĩa là được bảo

vệ để tránh xa khỏi thực tại tàn bạo được tầng lớp hạ lưu

chấp nhận như là lẽ đương nhiên ở đời. Cám

ơn

01/31/13 at 10:32 PM Mấy bữa nay bác viết hay ghê – hết viết tục rồi. Cám ơn nhiều. 08/30/12 at 9:11 PM Khong sao! Subject: Re: Tham Sorry NQT Thì ông chồng tôi cũng bắc kỳ vậy… đoạn bác viết về Sến-Ngô Bảo Châu, bác khinh không chừa một ai ngoài Bắc! Tôi là Bắc Kỳ mà. All My Best Wishes to U and Family NQT Trời ơi, sao bác miệt thị người Bắc dữ vậy, bác thù tới tận xương tủy, bác làm tôi nhớ đến đoạn 18, 19 Sách Sáng Thế (Cựu Ước) ông Abraham mặc cả với Chúa, nếu tìm ra được một người tốt trong thành phố Sodome-Gomorrhe thì xin Chúa tha cho thành phố khỏi bị hủy – nhưng không tìm ra được một ai... nên thành phố phải bị hủy. Bác «lãng mạn» quá, cứ mong chờ có một cú ngoạn mục của các nhân tài. Mong bác sức khỏe sống lâu để chờ ngày đó. http://www.catholic.org.tw/vntaiwan/vnbible/sangthe/sangthe18.htm http://www.catholic.org.tw/vntaiwan/vnbible/sangthe/sangthe19.htm [Note: Links broken] Tks. NQT Nhờ làm trang TV mà quen được hai vị [O & K], quả là không uổng quãng đời lưu vong!

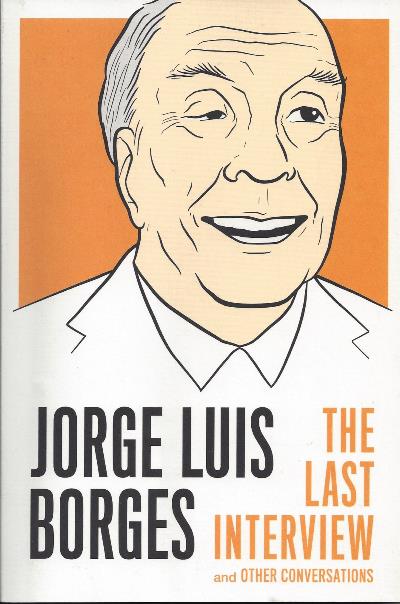

Borges: Từ đó nặng quá! LOPEZ LECUBE: When precisely do you feel that bronca? (1) BORGES: No, bronca is too strong a word. LOPEZ LECUBE: You never feel bronca? BORGES: I don't know, bronca is lunfardo for anger isn't it? I don't know, no, not anger, sometimes I feel deflated, but that's natural, and at my age ... old age is a form of deflation too, but why be angry about it? It's no one's fault. (1) A slang word for "frustration" or "anger." Bài thơ nào của ông mà ông cực khoái? Tại sao? Bài bảnh về ông?... Borges: Tớ đếch khoái thơ của tớ về tớ. Tớ khoái bài sonnet của tớ về Spinoza. Tớ viết hai sonnets về ông ta, có 1 dòng như vầy, Một người đàn ông sáng tạo ra Chúa ở trong bóng tối, người đàn ông đó, là Spinoza, who engenders God, his God, made of an infinite substance whose tributes will be infinite. Nếu bi giờ chúng ta đang ở thư viện của ông, bài thơ nào ông muốn tôi đọc cho ông nghe? Bài của Robert Frost Acquainted with the Night

By Robert Frost I have been one acquainted with the night. I have walked out in rain—and back in rain. I have outwalked the furthest city light. I have looked down the saddest city lane. I have passed by the watchman on his beat And dropped my eyes, unwilling to explain. I have stood still and stopped the sound of feet When far away an interrupted cry Came over houses from another street, But not to call me back or say good-bye; And further still at an unearthly height, One luminary clock against the sky Proclaimed the time was neither wrong nor right. I have been one acquainted with the night. Viết Mỗi

Ngày

Vấn đề

không hẳn đúng như cả hai vị Thế Uyên & TV đặt ra.

Lê Thị Thấm Vân published a note.trưa qua viết được một đoạn cho tiểu

thuyết mới (tạm đặt tên là ‘mía’. mía cũng

là tên của nhân vật xưng tôi). trước khi bắt tay

vào viết tiểu thuyết mía, tôi tự nhủ là hãy

giảm bớt tính/tình dục (mấy cuốn tiểu thuyết trước tôi

cũng tự nhủ như vậy), nhưng trưa nay đọc lại đoạn viết về món ‘hàu

của tháng giêng” viết trưa qua tôi lại thấy thấm đẫm,

nồng nàn da thịt. nó làm tôi nhớ tới cuốn sách

x...

...

Viết về sex rất khó, theo GCC. Viết không tới là nó biến thành dơ, tục. Khó hơn viết về tình yêu, bởi vì viết về sex, là độc giả không chỉ mê bướm mà còn mê cái đầu của người nữ nữa, vẫn theo Gấu. Và, [lại] thuổng Brodsky. Có cái gọi là đạo hạnh, rất cần nó, khi viết về sex, và cái này nằm ở trong nội lực của nhà văn. Vị Thế Uyên này, ngay từ trước 1975, Gấu đọc, là đã không chịu nổi. Và, rõ ràng là, sau 1975, đi tù VC ông ta thuộc bài lắm, viết tự kiểm thuộc loại tổ sư. Ông ta và bà con của ông ta, là Duy Lam, đi 1 đường viết chung 1 tập truyện ngắn, chôm mẹ cái tít của TTT, “nỗi chết không rời”. Cứ tỉnh bơ như người Hà Nội. Vị TV này, do Gấu được kết bạn FB, và nhờ thế, có đọc lai rai, và có ý nghĩ, văn của bà không chỉ về tính dục. Có cái gì sai ở đây, như trường hợp “nhà có cửa khóa trái”: Do được ngài tiên chỉ khen, thế là hỏng luôn cả 1 đời văn! http://harpers.org/ Tờ Harper’s số mới 200 th issue, Jan 2017, Tin Văn đã chôm bài viết về Modiano, nhà văn trẻ kiếm tiếng nói của mình. Nay đi thêm vài đường, nhân dịp đầu năm dương lịch. Cái hồi nhớ của Steiner, cái essay về nhà văn sao hay tự làm thịt mình, và cái truyện ngắn của Isaac Bashevis Singer, Cửa sổ nhìn ra thế giới. Tay này, bị Bà Huệ, Gió O, tố, nhờ Mafia Do Thái mà được Nobel văn chương. Không chỉ Bà Huệ, mà Milosz cũng tố, ưa xài đòn sex quá, và, quả có 1 chiến dịch bên lề hành lang nhằm ảnh hưởng lên Uỷ Ban Nobel. Tuy nhiên, ông là 1 trong những tác giả đầu tiên Gấu làm quen, khi ra được hải ngoại. Ông viết nhiều, có nhiều truyện thần sầu, Linda Lê cũng đã từng giới thiệu. Đầu năm đi 1 đường truyện ngắn, chắc cũng “có ní”. A young writer finds his voice on the radio UN DYBBUK AMOUREUX

Hồn ma si tình Isaac Bashevis Singer et son alter ego Singer và thế thân của ông Trong L’Anneau de Clarisse, Claudio Magris chào mừng Isaac Bashevis Singer, như một tay kể chuyện cổ gần gũi với "những bậc thầy vô ngã, vô tên của quá khứ, những nhà văn lớn lao giống như tất cả mọi người, và chẳng giống một người nào, bởi vì họ biến thành những con người nói bằng bụng, thay vì bằng miệng, và những nhân vật đa dạng, những hộp cộng hưởng, cho mọi thứ tiếng tơ đồng, của cõi sống." Như con quỉ cuối cùng, trong một truyện ngụ ngôn của mình, sống bằng cách gậm nhấm một cuốn sách cổ xưa [thuật chuyện núi rừng Hua Tát, bằng một thứ ngôn ngữ Mường Mán], Singer là một meshugah, một tên khùng, sống sót bằng cách, rút ra từ những huyền thoại Do Thái, và những kỷ niệm về một thế giới đã qua, lý do hiện hữu của mình. Lưu vong qua Mỹ vào năm 1935, khi đó ông 31 tuổi, ông viết bằng tiếng yiddish, và cộng tác trong việc dịch chúng qua tiếng Anh. Ông muốn viết bằng một ngôn ngữ chết, mà sự biến mất của nó báo hiệu sự suy tàn của nghệ thuật. Nhà văn yiddish, với ông, là một thứ dybbuk, một bóng ma, nhìn, và không ai nhìn thấy được. Viết nhiều, "thi sĩ của lưu vong, không phải theo kiểu Do Thái, mà là một thứ lưu vong đụng tới con người, và nhất là, con người-nhà văn đương thời", Claudio Magris nói về Singer. Singer cố làm bật ra, bằng một nỗi buồn nhuốm mầu thần bí, tính sống động, và cơn chao đảo, của một thế giới chìm xuồng. retour aux classiques

par Linda Lê UN DYBBUK AMOUREUX Isaac Bashevis Singer et son alter ego Dans L’Anneau de Clarisse, Claudio Magris saluait en Isaac Bashevis Singer un conteur proche de ces “grands écrivains impersonnels et anonymes du passé, qui ressemblent à tout le monde et à personne parce qu'ils se font les ventriloques indifférents des vies et des personnages les plus divers, et les caisses de résonance impartiales de toutes les cordes du vivre”. À la manière du dernier démon d’une de ses paraboles, qui se nourrit en rongeant un vieux livre de contes yiddish, Singer était un meshugah, un fou qui survivait en tirant des légendes juives et des souvenirs du monde d'hier sa raison d'être. Exilé aux Etats- Unis en 1935- il avait 31 ans -, il composait ses textes en yiddish, et collaborait à leur traduction en anglais. Il déclarait avoir conscience d'écrire dans une langue morte, dont la disparition annonce le déclin des arts. L'écrivain yiddish pour lui est une sorte de dybbuk, de spectre, qui voit mais n’est pas vu. Auteur prolifique, “poète de l'exil, pas seulement des Juifs mais de l'exil existentiel qui touche l'homme et surtout l'écrivain contemporain”, disait encore Claudio Magris, Singer s'est attaché à dépeindre, avec une mélancolie teintée de mysticisme, la vitalité et le chaos d'un univers qui a sombré. Le jeune Arele Greidinger, le narrateur de Shosha et l'alter ego romanesque de Singer, affirme sans ambages que le monde est un abattoir et un bordel. Fils de rabbin, tout comme Singer lui-même, et tout comme ce dernier lecteur de Weininger et de Spinoza, Arele se fraye un chemin dans la Varsovie de l'entre-deux-guerres: it écrit une pièce ou l'héroine tombe amoureuse de son dybbuk - on reconnait là l'ébauche de ce qui sera La Corne du belier de Singer. Une actrice américaine et un ancien charpentier qui a fait fortune se proposent de le lancer. L'aventure tourne court avant même d'être sur les rails. Loin de ce microcosme, qui prend de plus en plus conscience de la menace hitlerienne et se tourne vers Staline avant d'ouvrir les yeux sur la terreur qui règne au paradis bolchevique, Shosha, une femme enfant, un peu retardée, répresente l'innocence perdue. Arele poursuit son rêve, refuse de partir pour New York, et choisit de s'installer auprès de cette étrange créature, à peine capable de comprendre ce qu'il écrit. Fourmillant de personnages qui traversent la scène comme des evadés impatients de tout connaitre avant l'effondrement de ce à quoi ils ont cru, ce roman, qui développe un chapitre d'un livre autobiographique de Singer, Un jour de plaisir, est autant un chant d'amour qu'un kaddish pour les morts auxquels Singer offre un tombeau de papier. Shosha Isaac Bashevis Singer Trad. de l'anglais par Marie-Pierre Bay et Jacqueline Chnéour Ed. Stock, 380 p.,19 €. Le Magazine Littéraire, Mai, 2007 http://harpers.org/archive/2017/01/a-window-to-the-world/ Some writers begin to write with talent, quickly earn a reputation among readers and critics, and then are suddenly silenced forever. We had two such men at the Yiddish Writers’ Club in Warsaw. One, Menahem Roshbom, had managed, before he was thirty, to publish three novels. The other, Zimmel Hesheles, had at the age of twenty-three written one long poem. Both got enthusiastic reviews in the Yiddish press. But then, as the saying goes, their literary wombs closed up and never opened again. Roshbom was already in his fifties and Hesheles in his late forties when I became a member of the Writers’ Club. Both were considered good chess players. I often saw them playing together. Menahem Roshbom was always humming a tune, swaying, grimacing, and trying to pluck out the remaining few hairs from his salt-and-pepper goatee. He would raise his thumb and forefinger as if to move a piece, and then pull them back as if they had been singed. It was said that he was a better player than Hesheles, but toward the end of the game he inevitably lost his patience. Menahem Roshbom was a chain-smoker. His fingers and nails were stained yellow, and he suffered from a chronic cough. It was said that he smoked even while asleep. He was tall, emaciated, wrinkled, stooped. After he stopped writing fiction, he had taken to journalism and had become the head feuilletonist at one of the two Warsaw Yiddish newspapers. Although he was sick and it was said that he was consumptive, he carried on with women, mainly actresses from the Yiddish theater. He had in his lifetime divorced three wives, and the children of all his three wives came to him for money. His steady mistress was the wife of a Yiddish actor. It was never determined why her husband allowed her to be with Roshbom. I often heard it said that Roshbom deplored being too clever, too cynical. Frequently in his conversations, and even in his articles, he belittled the value of literature and the delusions of immortality. He had never allowed himself to be honored at a banquet. If someone called him a writer, Roshbom responded: “Maybe at one time . . . ”

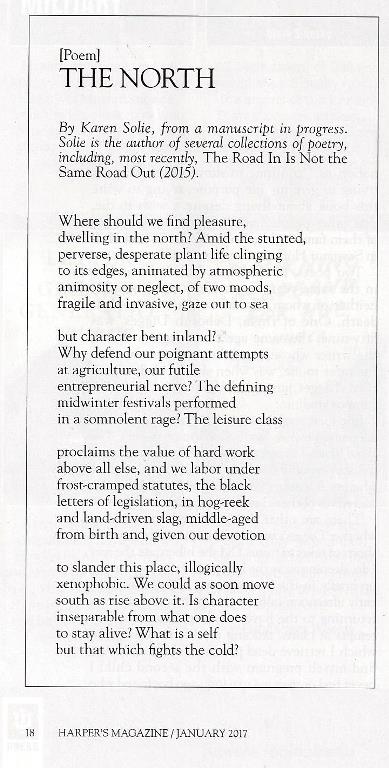

What is a self but that which fights the cold? Xứ Bắc Kít Gấu đọc Tô Hoài rất sớm, và giấc mộng, sẽ có ngày tới được nước Nam Kỳ, là do đọc ông mà có. Khi còn ở xứ Bắc, mỗi lần đói, mỗi lần rét, mỗi lần ăn miếng ăn, ăn thêm một câu nói, là giấc mơ sẽ có ngày tới được nước Nam Kỳ lại trỗi dậy. Cho tới khi tới được nước Tưởng thoả mãn, mà thoả mãn thực, nhưng, oái oăm thay, một nước Nam Kỳ khác xuất hiện! Lúc thì ở nơi BHD, và cái nước Nam Kỳ lần này, khốn nạn thay, lại chính là cái xứ Bắc Kỳ mà Gấu đã bỏ chạy!

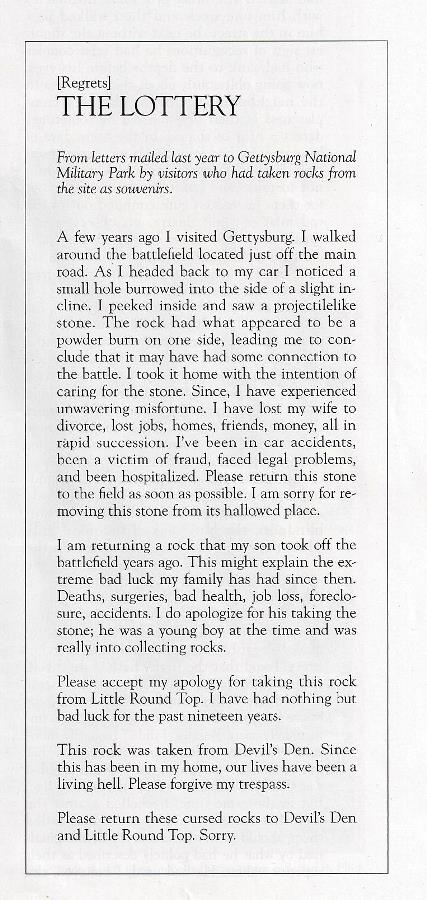

Ui

chao, liệu ba thứ chiến lợi phẩm, "Bắc Kít nhận hàng",

mang bad luck đến, cho, không chỉ xứ Bắc Kít?

Đọc, thì Gấu lại nhớ đến 1 câu chuyện khoa học giả tưởng, hình như do Đặng Trần Huân dịch, giới thiệu. Giống người chinh phục 1 hành tinh. Đến 1 phát, là chém, là giết, là hiếp, vô tư, thoải mái. Chẳng phải đợi 30 năm, mà đâu chỉ vài ngày, là xong. Bữa đó, sáng ngủ dậy, đếch tên nào thèm dậy. Hoá ra ở hành tinh này, chết, là 1 thứ Devil's bad luck! Milosz viết về vụ Singer đợp Nobel: Không xứng so với Chaim Grade. GRADE, Chaim. The Nobel Prize for Isaac Bashevis Singer was cause for violent controversies among Yiddish-speaking New York Jews. Grade was of much better background than Singer; in America, it's best to come from Wilno, worse to come from Warsaw, and worst of all from Galicia. Above all, however, in the opinion of the majority of the disputants, he was a much better writer than Singer, but little translated into English, which is why the members of the Swedish Academy had no access to his writings. Singer gained fame, according to this opinion, by dishonest means. Obsessively concerned with sex, he created his own world of Polish Jews which had nothing in common with reality-erotic, fantastic, filled with apparitions, spirits, and dybbuks, as if that had been the quotidian reality of Jewish towns. Grade was a real writer, faithful to the reality he described, and he deserved the Nobel Prize. Wilno was an important center

of Jewish culture-not just a local center, but on a world scale. Yiddish

was the dominant language there, and literature in that language had its

main support in Wilno, along with New York, as the number of peridicals

and books published there demonstrates. The city was better off before World

War I, when it belonged to Russia and profited from its position as a key

railroad junction and trading center. This came to an end when the city

was transferred to little Poland, although in terms of culture, the interwar

period was a time of blossoming. Something of the vitality of past years,

especially 1905-1914, also continued. Political parties that had been founded

in tsarist Russia were still active, with their prime concern the needs

of workers and a socialist revolution-most important of all, the Bund, a

separate Jewish socialist party, which wanted to be a movement of Yiddish-speaking

workers. It was a counterpart of sorts to the Polish Socialist Party, which,

however, since it was considered to be exclusively Polish, had relatively

few adherents in the city. It would not be accurate to link the creation

of the Jewish Historical Institute with the Bund, and yet in its aim of

preserving the cultural heritage of the cities and small towns where Yiddish

was used in daily life, one can detect the spirit of the Bund. The Communists

were rivals of the Bund and grew stronger with the years; in 1939, they apparently

had a majority of followers. Both these parties, in turn, were at war with

the Zionists and the Orthodox. This Jewish Wilno recognized

the attractiveness of Russian culture, but was separated from Soviet

Russia by the state border. The border was quite close, however, and

this produced a phenomenon peculiar to Wilno. Many young people, dreaming

of taking part in the "building of socialism," crossed the eastern border

without appropriate documents, enthusiastically ensuring their near and

dear ones that they would write from there. No one ever heard from any

of them again. They were sent straight to the Gulag. Chaim Grade belonged to the

group of young poets called Yung Vilne. In addition to Abraham Sutzkever,

I remember the name Kaczerginski. The attitude of this group toward the older

generation, somewhat like Zagary's, inclined us to make an alliance with

them. We were exactly the same age, and their "Young Wilno" used to come

to our readings. The poet Grade was a descendant

of an officer in Napoleon's army named Grade, who, wounded, and nursed

back to health by a Jewish family in Wilno, married into it and converted

to Judaism. Chaim's mother, who was very poor, was a street peddler whose

entire stock fit into a basket. Grade devoted many moving pages of his

oeuvre to that pious, hardworking, good woman. She appears against the background

of a milieu which followed all the religious customs, and whose common characteristic

was extreme poverty. Chaim's youth in Wilno did not

pass without political and personal conflicts. His father, Rabbi Shlomo

Mordechai, an addvocate of Hebrew and a Zionist, who held strong convictions

and was not much inclined to compromise, engaged in heated arguments with

the conservative rabbis. He raised his son to be a pious Jew. Chaim's

later history shows that he remained faithful to Judaism, in contrast to

the emancipated Singer. As a poet, Chaim quickly achieved recognition and

local fame, but he was distinguished from the majority of young people

who read Marx and sang revolutionary songs. The Communists' attempts at

attracting him to their side were not successful, and Grade became the object

of violent attacks. Worse yet, he fell in love with Frumme-Liebe, who was

also the daughter of a rabbi and from a family of Zionists who emigrated

to Palestine. His Communist colleagues tried in vain to interfere with their

marriage. These details can be found in

his four-hundred-page novel memoir called, in English translation, My Mother's Sabbath Days. There he tells in

detail about his wartime experiences, beginning with the entry of Soviet

troops into the city. His friends' enthusiasm contrasted with the stony

sadness of the crowd at the mass in the Wilno cathedral, where he went out

of compassion. The chaos of the German invasion in June 1941 separated him

from his beloved wife. They were supposed to meet a couple of days later,

but he never saw her again. She died, as did his mother, in the Wilno ghetto.

A wave of fleeing refugees carried him to the East. After many peripatetic

(once, they wanted to shoot him as a German spy) he made his way to Tashkent.

After the war, he emigrated to New York. He always writes about the Russians

with love and respect. He insists that he never encountered any signs of

anti-Semitism in Russia. His colleagues from the Yung

Vilne group, Sutzkever and Kaczerginski, were in the ghetto and then

joined the Soviet partisan troops. Sutzkever wound up in Israel, where

he edited the only quarterly devoted to poetry in the dying language

of Yiddish, Di Goldene Keyt (The Golden Chain).

In America, the poet Chaim Grade

developed into a prose writer, and like Singer, who attempted to recover

the vanished world of the Jewish towns of Poland, he immersed himself

in the past, writing about the shtetls of Lithuania and Belorussia. Singer

engaged in fantasy and offended many of his readers; Grade was attentive

to the accuracy of the details he recorded and has been compared with Balzac

or Dickens. His main theme appears to be the life of the religious community,

which he knows well, especially the problems of families in which the wife

works to earn money and the husband pores over holy books. One collection

of novellas is even called Rabbis and Wives. I became interested in Grade

thanks to my contact with his second wife, his widow. After his death

in 1982 (he was seventy-two years old), she began energetically promoting

his work and collaborating with his English translators. MILOSZ'S ABC'S Ông sinh năm 1904, tại Ba Lan, di cư sang Mỹ năm 1935, và một thời gian làm ký giả cho tờ báo cộng đồng Jewish Daily Forward, tại New York City. Chỉ viết văn bằng tiếng Iddish, và được coi như nhà văn cuối cùng, và có lẽ vĩ đại nhất của "trường" văn chương Iddish. Vĩ đại hơn, ông là nhà văn Iddish đầu tiên, sống nhờ viết văn. Chúng được dịch ra tiếng Anh, rồi ông được trao tặng Nobel (1978). Là một trong số những dịch giả truyện của mình, với ông, tiếng Anh còn là ngôn ngữ mẹ đẻ thứ hai, nhưng ông thú nhận, ông viết bằng tiếng Iddhish, vì đây là "tử ngữ', và truyện của ông là để cho những người đã chết, đọc. Trong Nhà Văn Hiện Đại, khi Nguyễn Tuân mới xuất hiện, Vũ Ngọc Phan đã tiên đoán, văn tài của ông sẽ có ảnh hưởng rất lớn tới lớp sau. Có thể mượn nhận định của Sartre, về chủ nghĩa Mác-xít: tùy bút của Nguyễn Tuân quả đã "không thể vượt được", nhất là chất khinh bạc của nó, đã "di truyền" mãi mãi về sau này. Như nhìn ra "phần số khắc nghiệt", để bù lại, trong truyện ngắn, Nguyễn Tuân thường viết về những người đã chết. Ở đó, chất khinh bạc mất hẳn, hoặc được ngôn ngữ kỳ diệu của ông đẩy tới tột cùng, biến thành lòng nhân hậu. Borges

Conversations

You Only Need To Be Alive Bạn

chỉ cần, sống.

To be alive Một trong những bài điểm sách mà Gấu nhớ đời, khi mới vào làng văn, là bài viết về cuốn Nỗi Bơ Vơ Bầy Ngựa Hoang, của Trần Hoài Thư, khi giữ mục Điểm Sách cho trang VHNT cuối tuần của nhật báo Tiền Tuyến, của quân đội VNCH, thời gian TTT phụ trách, sau ông chán, thảy qua thằng em. Khi viết, nhân Y Uyên vừa mới chết, thằng em trai của Gấu cũng tử trận, trước Mậu Thân chừng 1 năm. Trong đầu toàn hình ảnh chết chóc, Gấu phán, bạn chỉ cần sống sót, vì sau đó, bạn "bèn" đụng 1 trận chiến khác, khủng khiếp chẳng kém: Văn chương! Câu phán, "You only need to be alive", trong "Borges, Tám Bó", Borges cho biết, là của 1 bà làm bếp, hay tớ gái... Có thể nói, câu phán “chỉ cần còn sống”, quả đúng là 1 cái bad luck cho toàn 1 cõi văn chương Ngụy, trước 1975, không phải cho "những người đã chết đều có thực", như Y Uyên, mà cho chính những kẻ mà chúng cần "to be alive" Đúng cái ý vị thân hữu: Xạo! Tưởng Niệm Một chuyến đi [NQT] "Nguyễn

Tuân hỏi tôi 07/07/2010

"Nguyễn Tuân nổi tiếng

với tùy bút, và tùy bút Nguyễn Tuân,

nổi đình nổi đám vì chất khinh bạc của nó. Những

người viết sau này, không thể nào tới được cái

chất khinh bạc "ròng" như vậy, đành phải thay bằng giọng

thầy đời, giọng uyên bác, giọng có đi Tây, đi

Tầu, có ở Paris, có biết khu "dân sinh" Saint-Germain-des-Prés...

Ra cái điều đi hơn Nguyễn Tuân! Trúc Chi có thể

"hơn" Nguyễn Tuân ở cái khoản đi, nhưng "may thay", chân

truyền Nguyễn Tuân ở cái khoản khinh bạc: khinh bạc như là

cực điểm của lòng nhân hậu. Lòng nhân hậu, hay

hồn nhân hậu này, theo tôi nên "dịch ra tiếng Tây"

bằng chữ la nostalgie, vốn thường được hiểu là hoài hương." "Mot chuyen di" cua GNV hay qua.

Nguoi trong nuoc cung dang viet hang loat ve Nguyen Tuan, nhung khong hieu

sao, doc ho cu co cam giac nhu dang nghe mot nhom nguoi noi chuyen voi nhau

trong mot... dam gio^~…… HA Có hai nhà văn

“bậc thầy”, đặc Bắc Kít, nhưng Bắc Kít đếch đọc được, do

thiếu cái gọi là lòng nhân hậu, có thể,

là Nguyễn Tuân và Tô Hoài. Bài viết “Một Chuyến Đi”

của Gấu, là để bye bye đám bạn quen biết qua tờ Văn Học của

NMG, như Trúc Chi, Tạ Chí Đại Trường..... Võ Phiến, khi khen Nguyễn

Tuân, đã nhắc tới cái cảnh, một em Bắc Kít, cong

người, tránh 1 cái hôn, hay 1 làn roi, trong

trò "cô đầu" của xứ Bắc Kít. Gấu nhớ là, khi

đọc, đã lắc đầu, những câu văn đó, là chỉ để

dành cho lũ độc giả mắt trắng dã! Với mắt xanh, với bạn văn, NT

dùng những câu văn rất ư là bình thường, giản

dị, thí dụ như đoạn nói chuyện với Tô Hoài về

anh chàng Két nào đó, hay câu văn kết thúc

Chiếc Lư Đồng Mắt Cua: Xuyến người bên lương hay

bên giáo? “Phở”, của NT, là cũng dành cho dân thành thị, đồ tứ chiếng, lạc chợ trôi sông. Với dân quê xứ Bắc Kít, NT có những món khác, thí dụ cơm nắm chấm muối vừng. Đọc ông, hay đọc Tô Hoài, khi không bị Cái Ác Bắc Kít hành hạ, là phải tìm ra những món ăn đó, về mặt tâm linh.

Lần viết “Chữ Người Tử Tù”, cho mục Tạp Ghi của tờ Văn Học, ông chủ chi địa, đọc tới những dòng về Nguyễn Tuân, thú quá, bèn gật gù, ông viết văn bằng Tạp Ghi. Tôi không viết được như vậy!

Cá nhân người viết làm quen với Nguyễn Tuân rất sớm, phải nói là quá sớm. Mới biết đọc, biết viết, "thằng bé" đã nghe đọc văn ông, ở những bậc cha chú trong gia đình. Người bác trong lúc tâm đắc với một người bạn về những viên ngọc vương vãi, trên con đường từ giếng trời trở về trần, vô tình để mãi những viên ngọc trong trí tưởng của đứa cháu. Thế đấy, cậu bé đã dùng những viên ngọc như vậy để đánh dấu những trang sách hồng, Ông Đồ Bể, Cái Ấm Đất, của Khái Hưng. Đánh dấu những trang sách của một chuyện tình (chúng làm cho những lần chia ly bớt thê thảm đi một chút); của cuộc chiến: như những viên đất ném theo, ném theo mãi, xuống lòng huyệt... Last Christmas of the War by Primo Levi (1986) Primo Levi knew the realities of winter. Many of the memoirs he wrote of his time as a prisoner at Auschwitz are coloured as much by biting cold and endless grey snow as by barbarism and industrial slaughter. This brief piece takes place in the final winter of the war, just before the events described in The Truce, the story of Levi’s long journey home. And it consists of little more than the arrival of a package of biscuits from his family – a dangerous offence in a concentration camp. This small gift, coming as it does after the harrowing things he has experienced, is transmuted into an almost miraculous event, and his giddiness at the prospect of satiety is palpable. But it’s the glints of an intrinsic decency Levi is able to locate in his fellow man, even under the shadow of the darkest evidence of his capacity for brutality, which form the heart of this tale. Đọc 1

phát, thì bèn nhớ đến Giáng Sinh tưởng là

"cuối cùng" của Trại Panat Nikhom, của GCC! "Nhưng nếu không vì dung nhan tàn tạ, chắc gì Thầy đã nhận ra em?" Những người từng

ở Trại Cấm Sikiew, Thái Lan, chắc khó quên được Giáng

Sinh 1991. Chiều ngu ngơ phố thị

Ngày ủ dột Buồn dậy muộn Câu thơ trong giấc ngủ bỏ quên Nhớ em thảm thiết. Trong câu thơ chắc có chút hạnh phúc Cho nên tình yêu là vất vả đi tìm Tìm em như thể tìm chim Chim bay biển Bắc anh tìm biển Đông. Chiều ngu ngơ phố thị Mơ gặp em giữa đám người xa lạ Với nụ cười thật ngày xưa Khi em từ giã. Kiếp trước tôi có nợ nần chi ông đâu Mà sao kiếp này ông đòi kiếp khác? Tôi đã nói ông đừng gặp tôi nhiều Khi tôi đi rồi Ông sẽ khổ Nhưng thôi ông hãy quên tôi đi Quên đi, quên đi.... Em ở đâu, ở đâu Thèm một chút mồ hôi trên ngấn cổ Em ở đâu, ở đâu Thèm nụ hôn sầu Lời biếng nói Đôi tay mềm mại mãi trong tôi. Lament for Yin Yao

We followed you back for your burial on Mount Shihlo And then through the greens of oaks and pines we rode away home Your bones are there under the white clouds until the end of time And there is only the stream that flows down to the world of men. Chúng tớ đưa đám bạn DC rồi trở về nhà Xanh xanh những mấy ngàn dâu, ngàn thông, ngàn sồi… Xương của bạn DC bi giờ ở bên dưới những đám mây trắng kia Cho đến tận cùng, của tận cùng, của thời gian Chỉ có dòng suối là từ phía mây bạc Chảy về trần gian của lũ chúng tớ RIP Gấu

không phải bạn DC.

Gấu gặp DC độc nhất, lần qua Cali, ở nhà NDT, nhưng do DC và bạn quí của ông là nhà thơ ngồi bên ly cà phê ghé, nên Gấu phải nhường phòng cho cả hai, và bèn khăn gói qua nhà bạn Bạn. Giả như không qua nhà bạn Bạn, thì ngỏm củ tỏi ở PLT, bữa quá chán đời rồi! Đời Gấu cực lạ, lần nào tính tự làm thịt mình, là lần đó, bị kỳ đà cản mũi. Tếu thế. Về già, ngẫm lại, Gấu mơ hồ 1 điều, Lão Tặc Thiên hình như cần Gấu làm cho Hắn 1 cái gì đó, nên không cho Gấu ngỏm vội Chờ 1 tí, lát nữa thì được. Cứ như anh nhà quê ra tỉnh đến Trước Pháp Luật.

Hãy nói cho

tôi

Tại sao nỗi cô đơn của tôi Bài hát của tôi Giấc mơ của tôi Trì hoãn Lâu như thế? Khuyên

Nè bồ tèo, nghe nè Sinh dữ Tử lành Hãy có tí ti tình yêu Ở giữa Harlem

Chuyện gì xẩy ra cho giấc mơ bị trì hoãn? Liệu nó khô queo dưới nắng gắt như lửa? Hay mưng mủ như nỗi đau Rồi bỏ chạy? Hay thối rữa như đồ ăn thiu Hay tráng tí đường Như cục kẹo? Có khi nào nó trũng xuống Như chở nặng quá? Mà, có khi nào Nó nổ cái đùng? WINTER MOON How thin and sharp is the moon tonight!

Trăng Đông Mỏng làm sao, sắc làm

sao, trăng đông lạnh đêm nay SUICIDE'S NOTE The calm, Mẩu giấy để lại trước khi trầm minh Mặt sông lạnh/lặng lẽ VAGABONDS We are the desperate Lũ Ma Cà Bông Chúng tớ là 1 lũ tuyệt

vọng Langston Hughes

Gấu

tính sống hoài hoài

Bữa trước ở PLT, Gấu phán, Tớ đang chết Cả hai đều đúng. Hai đứa mình phải luôn sẵn sàng cho khoảnh khoắc - những tai ương, niềm vui, và nỗi buồn Today at 8:07 PM Dear Gấu Nhà Văn, "When I first met Karen Zebroff she said "When the Chela (student) is ready, the Guru (teacher) appears." I immediately responded to this ancient traditional saying of Yoga teachers, "No, Kareen, when the Guru becomes ready or perfect, the student appears." - Foreword by Swami Shyam Acharya for Yoga and Nutrition with Kareen Zebroff Welcome to Little SaiGon, Gấu Nhà Văn. Sent from my iPad Tks Take Care Closing time

“THERE’S this poet from Canada…He plays pretty good guitar, and he’s a wonderful songwriter, but he doesn’t read music, and he’s sort of very strange.” It was an unconventional pitch from a manager hoping to attract the attention of John Hammond, one of the most influential record producers around. But Mr Hammond was intrigued, and decided to invite the poet to lunch. Once they had eaten, the young Leonard Cohen sat down to play a dozen of his tunes. Mr Hammond was hooked: “You’ve got it, Leonard”. Within a week Mr Cohen was working on his first album and some of his finest songs, “Sisters of Mercy”, “Suzanne” and “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye” in the studios of Columbia Records. It was 1967, and he was in his 30s. Back in college he was in a folk band with a couple of guys: they wore Buckskin jackets and played their biggest gigs in church basements and school halls. But most of the years since had been spent chasing his ambitions as a poet, writing books fuelled by drugs and making love on an idyllic island in Greece. This did not pay the bills, however, and when the release of his second book “Beautiful Losers” came under fire for having “obscure” sexual content, Mr Cohen decided it was time to look elsewhere. He set off to Nashville and on the way found himself captivated by the scene in New York. He saw music as his second calling, and rightly so. His words were all the more beautiful put to sound. After 14 albums and a career that spanned into his 80s, Mr Cohen remained unique in his ability to produce songs that could consume the listener, envelop them in darkness and reflection, and offer great comfort and hope all the while. He articulated like no other the universal unease and helplessness felt by society in a changing world. Some, like “If it be your will”, are more akin to prayer than song; others see Mr Cohen having fun, gently mocking those who praise him: “I was born like this, I had no choice, I was born with the gift of a golden voice.” Despite “Hallelujah” going on to become one of the most widely-covered songs in history, some felt that the weight of his songs may have prevented him from reaching the same commercial success enjoyed by that of his contemporary Bob Dylan, among others. Mr Cohen built up a loyal fan base and widespread appreciation for his transfixing lyrics and painstaking craftsmanship (it took him years to write a single song, a process he described as “like a bear stumbling into a beehive or a honey cache”). Even as Mr Dylan received the Nobel prize for literature, many wondered whether Mr Cohen would have been a more deserving candidate. On stage, few artists could inspire an audience to weep, to console and to laugh like he did. During his first major tour back in 1972, Mr Cohen implored the audience to stop applauding: he was too nervous, too distracted, and he couldn’t go on singing. When he returned to the stage to sing “So Long, Marianne”, based on former girlfriend and muse Marianne Ihlem, the audience joined in and Mr Cohen and his band were reduced to tears. Backstage and broken, he noted how overwhelming the experience had been. In the twilight of his life, the conflicted states of mind and nerves that plagued every show of his youth seemed to all but disappear. Forced back on the road after his manager, Kelley Lynch, left him financially broke, Mr Cohen truly came into his own playing three and a half hour sets, right up to each venue’s curfew. In the opening pages of her biography on him, Sylvie Simmons describes Mr Cohen as “a courtly man, elegant, with old-world manners”. Anyone who saw him live knows that to be true. Surrounded by his band, sharing anecdotes and thanks, Mr Cohen electrified the audience with a charm and wit so at odds with the “godfather of gloom” reputation bestowed upon him. His death last week was met with deep sadness and countless tributes; some, like Kate McKinnon’s heartfelt performance on SNL, a fitting end to a tumultuous few days. Only a month before, Mr Cohen released what was to be his last album, “You Want It Darker”, to critical acclaim. The opening track sees Mr Cohen proclaim “Hineni, hineni, I’m ready, my lord”: it seemed prophetic then, and even more so now. The world may not be ready for his absence, but solace can be found in the body of work he took great care to leave behind. Còm: he should have won over Dylan for sure. far more eloquent and subtle. Bảnh

hơn... họ Trịnh nhiều! "songs that could consume the listener, envelop them in darkness and reflection, and offer great comfort and hope all the while" - a great description. His self-effacing, gracious wit is hard to find. Độc giả mà còm thế này, quả là thần sầu.Nói thì "gom vào mình", nhưng quả là cái cảm giác Gấu lần đầu nghe “Ngày Mai Đi Nhận Xác Chồng”, ở Trại Cải Tạo VC ở Nhà Bè. Đó là lần đầu tiên Gấu nghe bản nhạc, nó “đốt cháy người nghe, ôm lấy họ trong bóng tối, trong bóng tang”... Gấu đã từng đi nhặt xác đứa em trai tử trận….

|