Dịch thuật | Dịch ngắn | Đọc sách | Độc giả sáng tác | Giới thiệu | Góc Sài gòn | Góc Hà nội | Góc Thảo Trường

Thư tín | Phỏng vấn | Phỏng vấn dởm | Phỏng vấn ngắn

Giai thoại | Potin | Linh tinh | Thống kê | Viết ngắn | Tiểu thuyết | Lướt Tin Văn Cũ | Kỷ niệm | Thời Sự Hình | Gọi Người Đã Chết

Ghi chú trong ngày | Thơ Mỗi Ngày | Nhật Ký | Chân Dung | Jennifer Video

|

|

Happy Mother's Day Maya

Angelou: a titan who lived as though there were no tomorrow America has

not just lost a talented Renaissance woman and a gifted raconteur– it

has lost

a connection to its recent past The poet and

memoirist Maya Angelou died on May 28th, at the age of eighty-six. A

civil-rights activist and a professor at Wake Forest University,

Angelou—born

on April 4, 1928, in St. Louis, Missouri—was the author of works

including “I

Know Why the Caged Bird Sings,” and received awards including the

National

Medal of Arts and the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Her public life

spanned

decades and included a nomination for the Pulitzer Prize, as well as

dozens of

honorary degrees. Happy Mother's Day Evening Walk You give the

appearance of listening The high

leaves like my mother's lips Everything

quiet. Light The sky at

the road's end cloudless and blue. -Charles

Simic Đi dạo vào

buổi chiều tối Tụi mi làm

ra vẻ Những chiếc

lá cây ở trên cao thì giống môi của bà má Gấu Mọi vật yên

tịnh Bầu trời ở

cuối con lộ thì không có mây, màu xanh  A New Étranger One of the

most widely read French novels of the twentieth century, Albert Camus’s

L’Étranger,

carries, for American readers, enormous significance in our

cultural understanding of midcentury French identity. It is

considered—to what

would have been Camus’s irritation—the exemplary existentialist novel. Yet most

readers on this continent (and indeed, most of Camus’s readers

worldwide)

approach him not directly, but in translation. For many years, Stuart

Gilbert’s

1946 version was the standard English text. In the 1980s, it was

supplanted by

two new translations—by Joseph Laredo in the UK and Commonwealth, and

by

Matthew Ward in the US. Ward’s highly respected version rendered the

idiom of

the novel more contemporary and more American, and an examination of

his

choices reveals considerable thoughtfulness and intuition. Each

translation is, perforce, a reenvisioning of the novel: a translator

will

determine which Meursault we encounter, and in what light we understand

him.

Sandra Smith—an American scholar and translator at Cambridge

University, whose

previous work includes the acclaimed translation of Irène Némirovsky’s Suite

Française—published in the UK in 2012 an excellent and, in

important ways, new

version of L’Étranger. THE WILLOW And a decrepit bunch of

trees. Pushkin I grew up

where all was patterned and silent, 1940 Anna Akhmatova Liễu Và một nhúm cây già Pushkin Tôi lớn lên

khi tất cả đều tỏ ra gương mẫu và im lặng Naturally

enough, poems of this sort couldn't be published, nor could they even

be

written down or retyped. They could only be memorized by the author and

by some

seven other people since she didn't trust her own memory. From time to

time,

she'd meet a person privately and would ask him or her to recite

quietly this

or that selection as a means of inventory. This precaution was far from

being

excessive: people would disappear forever for smaller things than a

piece of paper

with a few lines on it. Besides, she feared not so much for her own

life as for

her son's who was in a camp and whose release she desperately tried to

obtain for

eighteen years. A little piece of paper with a few lines on it could

cost a lot

and more to him than to her who could lose only hope and, perhaps,

mind. The days of both, however,

would have been numbered had the

authorities found her "Requiem," a cycle of poems describing an

ordeal of a woman whose son is arrested and who waits under prison

walls with a

parcel for him and scurries about the thresholds of state's offices to

find out

about his fate. Now, this time around she was autobiographical indeed,

yet the

power of "Requiem" lies in the fact that Akhmatova's biography was

too common. This Requiem mourns the mourners: mothers losing sons,

wives

turning widows, sometimes both as was the author's case. This is a

tragedy

where the choir perishes before the hero. The degree of compassion

with which the various voices of

this "Requiem" are rendered can be explained only by the author's

Orthodox faith; the degree of understanding and forgiveness which

accounts for

this work's piercing, almost unbearable lyricism, only by the

uniqueness of her

heart, herself and this self's sense of Time. No creed would help to

understand, much less forgive, let alone survive this double widowhood

at the hands

of the regime, this fate of her son, these forty years of being

silenced and

ostracized. No Anna Gorenko would be able to take it. Anna Akhmatova

did, and

it's as though she knew what there was in store when she took this pen

name. At certain periods of

history it is only poetry that is capable

of dealing with reality by condensing it into something graspable,

something

that otherwise couldn't be retained by the mind. In that sense, the

whole

nation took up the pen name of Akhmatova-which explains her popularity

and

which, more importantly enabled her to speak for the nation as well as

to tell

it something it didn't know. She was, essentially, a poet of human

ties:

cherished, strained, severed. She showed these evolutions first through

the

prism of the individual heart, then through the prism of history, such

as it

was. This is about as much as one gets in the way of optics anyway. These two perspectives

were brought into sharp focus through

prosody which is simply a repository of Time within language. Hence, by

the

way, her ability to forgive-because forgiveness is not a virtue

postulated by creed

but a property of time in both its mundane and metaphysical senses.

This is

also why her verses are to survive whether published or not: because of

the

prosody, because they are charged with time in both said senses. They

will

survive because language is older than state and because prosody always

survives history. In fact, it hardly needs history; all it needs is a

poet, and

Akhmatova was just that. -JOSEPH

BRODSKY

30.4.2014

Millions

were dead; everybody was innocent. I lived

well, but life was awful. On the pay

channel, a man and a woman Charles

Simic Phòng Ngủ

Thiên Đàng Ba triệu Mít

chết Một người đàn ông và một người đàn bà Trao đổi những cái hôn thèm khát Xé nát quần áo của nhau Gấu trố mắt nhìn Âm thanh tắt và căn phòng tối Trừ màn hình, Đỏ như máu Hồng như Đông Phương Hồng Chế Lan Viên

thường nhắc câu này của Tế Hanh, không ghi xuất xứ : Sang bờ tư

tưởng ta lìa ta, Câu thơ diễn

tả tâm trạng người nghệ sĩ thời Pháp thuộc bước sang đời Cách mạng sau

1945, phải

“lột xác” để sáng tác, lìa bỏ con người trí thức tiểu tư sản, mong hòa

mình với

hiện thực và quần chúng. Câu thơ có hai mặt : tự nó, nó có giá trị thi

pháp,

tân kỳ, hàm súc và gợi cảm. Là câu thơ hay. Nhưng trong ý đồ của tác

giả, và

người trích dẫn, thì là một câu thơ hỏng, vì nó chứng minh ngược lại

dụng tâm

khởi thủy. Rõ ràng là câu thơ trí thức tiểu tư sản suy thoái.

Gậy ông đập

lưng ông. Đây là một vấn đề văn học lý thú. Thơ Mỗi Ngày Poems on the

Underground The Wider World Two Poems Written at Maple

Bridge

Night Mooring

Moon set, a

crow caws, written c. AD 765 Chang Chi Translated

by Gary Snyder At MapLe

Bridge

Men are

mixing gravel and cement

Gary Snyder Nguyệt lạc ô

đề sương mãn thiên Đỗ Thuyền

Đêm Ở Bến Phong Kiều Trăng tà chiếc

quạ kêu sương Tản Đà dịch Poems on the

Underground Seasons Wet Evening

in April The birds

sang in the wet trees Patrick Kavanagh Chiều Ướt, Tháng Tư Chim hót trên

cành ướt Winter

Travels who's typing

on the void tongues in

the night Bei Dao Translated by David Hinton with Yanbing Chen Du ngoạn Mùa

đông người gõ lên

quãng không những giọng

nói trong đêm đi vô phòng Bắc Đảo Rilke

THE FIRST ELEGY Who, if I cried out, would hear me

among the Angels? Ai, nếu tôi kêu lớn, sẽ nghe, giữa

những Thiên Thần? Rilke For me, the

happy owner of the elegant slim book bought long ago, the Elegies

represented

just the beginning of a long road leading to a better acquaintance with

Rilke's

entire oeuvre. The fiery invocation that starts “The First Elegy” -

once again:

"Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the Angels' / Orders? And

even

if one of them pressed me / suddenly to his heart: 1'd be consumed / in

his

more potent being. For beauty is nothing / but the beginning of terror,

which

we can still barely endure" -had become for me a living proof that

poetry

hadn't lost its bewitching powers. At this early stage I didn't know

Czeslaw

Milosz's poetry; it was successfully banned by the Communist state from

the

schools, libraries, and bookstores-and from me. One of the first

contemporary

poets I read and tried to understand was Tadeusz Rozewicz, who then

lived in

the same city in which I grew up (Gliwice) and, at least

hypothetically, might

have witnessed the rapturous moment that followed my purchase of the

Duino

Elegies translated by Jastrun, might have seen a strangely immobile boy

standing in the middle of a side- walk, in the very center of the city,

in its

main street, at the hour of the local promenade when the sun was going

down and

the gray industrial city became crimson for fifteen minutes or so.

Rozewicz's

poems were born out of the ashes of the other war, World War II, and

were

themselves like a city of ashes. Rozewicz avoided metaphors in his

poetry,

considering any surplus of imagination an insult to the memory of the

last war

victims, a threat to the moral veracity of his poems; they were

supposed to be

quasi-reports from the great catastrophe. His early poems, written

before

Adorno uttered his famous dictum that after Auschwitz poetry's

competence was

limited-literally, he said, "It is barbaric to write poetry after

Auschwitz"-were already imbued with the spirit of limitation and

caution. Adam Zagajewski: Introduction Với tôi người sở hữu hạnh phúc, cuốn sách

thanh nhã, mỏng manh, mua từ lâu, “Bi Khúc” tượng trưng cho một khởi

đầu của

con đường dài đưa tới một quen biết tốt đẹp hơn, với toàn bộ tác phẩm

của Rilke.

“Bi Khúc thứ nhất” - một lần nữa ở đây: “Ai, nếu tôi la lớn - trở thành

một chứng

cớ hiển nhiên, sống động, thơ ca chẳng hề mất quyền uy khủng khiếp

của nó. Vào lúc đó, tôi chưa biết thơ của Czeslaw Milosz, bị “VC Ba

Lan”, thành

công trong việc tuyệt cấm, ở trường học, nhà sách, thư viện, - và tất

nhiên,

tuyệt cấm với tôi. Một trong những nhà thơ cùng thời đầu tiên mà tôi

đọc và cố

hiểu, là Tadeusz Rozewicz, cùng sống trong thành phố mà tôi sinh trưởng, (Gliwice), và, có

thể chứng kiến, thì cứ giả dụ như vậy, cái giây phút thần tiên liền

theo sau, khi

tôi mua được Duino Elegies, bản dịch của Jastrun - chứng kiến

hình ảnh một

đứa bé đứng chết sững trên hè đường, nơi con phố trung tâm thành phố,

vào giờ cư

dân của nó thường đi dạo chơi, khi mặt trời xuống thấp, và cái thành

phố kỹ nghệ

xám trở thành 1 bông hồng rực đỏ trong chừng 15 phút, cỡ đó – ui chao

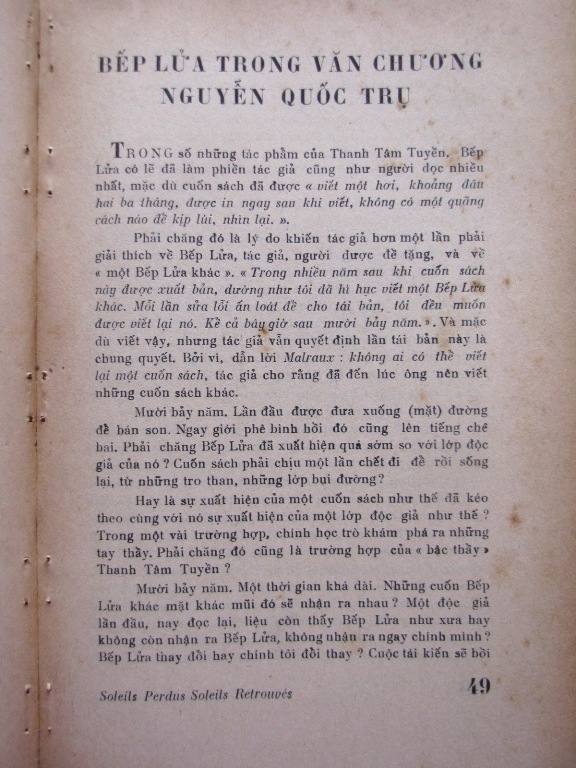

cũng chẳng

khác gì giây phút thần tiên Gấu đọc cọp cuốn “Bếp Lửa”, khi nó được

nhà xb đem

ra bán xon trên lề đường Phạm Ngũ Lão, Sài Gòn – Thơ của Rozewicz như

sinh ra từ

tro than của một cuộc chiến khác, Đệ Nhị Chiến, và chính chúng, những

bài thơ, thì

như là một thành phố của tro than.

Rozewicz tránh sử

dụng ẩn dụ trong thơ của mình, coi bất cứ

thặng dư của tưởng tượng là 1 sỉ nhục hồi ức những nạn nhân của cuộc

chiến sau

chót, một đe dọa tính xác thực về mặt đạo đức của thơ ông: Chúng

được coi

như là những bản báo cáo, kéo, dứt, giựt ra từ cơn kinh hoàng, tai họa

lớn. Những

bài thơ đầu của ông, viết trước khi Adorno phang ra đòn chí tử, “thật

là ghê tởm,

man rợ khi còn làm thơ sau Lò Thiêu”, thì đã hàm ngụ trong chúng, câu

của

Adorno rồi.  Note: Có 1 sự

trùng hợp ngẫu nhiên, nhưng thật ly kỳ thú vị, không chỉ về cái cảnh

Gấu chết sững

trong nắng Sài Gòn, khi đọc cọp – khám phá ra - Bếp Lửa, khi cuốn sách được nhà

xb Nguyễn Đình Vượng cho đem bán xon trên hè đường Phạm Ngũ Lão,

nhưng còn ở điều này:

Cuốn sách Bếp Lửa đã sống

lại, từ tro than, bụi đường Xề Gòn.  Samuel

Beckett KAFKA WAS BORN IN A building on the square of Prague's Old Town on July 3, I883. He moved several times, but never far from the city of his birth. His Hebrew teacher recalled him saying, "Here was my secondary school, over there in that building facing us was the university, and a little further to the left, my office. My whole life-" and he drew a few small circles with his finger "-is confined to this small circle." The building

where Kafka was born was destroyed by a great fire in I889. When it was

rebuilt

in 1902, only a part of it was preserved. In 1995, a bust of Kafka was

set into

the building's outer wall. A portent of the Prague Spring, Kafka was

finally

recognized by the Czech communist authorities, hailed as a

"revolutionary

critic of capitalist alienation."

In a letter

to a friend, he wrote: "There is within everyone a devil which gnaws

the

nights to destruction, and that is neither good nor bad, rather, it is

life: if

you did not have it, you could not live. So what you curse in yourself

is your

life. This devil is the material (and a fundamentally wonderful one)

which you

have been given and which you must now make use of. . . . On the

Charles Bridge

in Prague, there is a relief under the statue of a saint, which tells

your story.

The saint is sloughing a field there and has harnessed a devil to the

plough.

Of course, the devil is still furious (hence the transitional stage; as

long as

the devil is not satisfied the victory is not complete), he bares his

teeth,

looks back at his master with a crooked, nasty expression and

convulsively

retracts his tail; nevertheless, he is submitted to the yoke. . . ." Tòa nhà nơi Kafka ra đời, bị một trận cháy lớn tiêu hủy vào năm 1889. Khi xây cất lại vào năm 1902, chỉ 1 phần được giữ lại. Vào năm 1995, một bức tượng nửa người của ông được dựng lên trong toà nhà, tường phía ngoài. Một điềm triệu của Mùa Xuân Prague, Kafka sau cùng được nhà cầm quyền CS Czech công nhận, như là một “nhà phê bình cách mạng về sự tha hóa của chế độ tư bản”. Trong 1 lá

thư cho bạn, Kafka viết, luần quần trong bất cứ 1 ai, là một con quỉ,

nó gậm đêm,

đến tang thương, đến hủy hoại, và điều này, đếch VC, và cũng đếch Ngụy,

hay đúng

hơn, đời Mít là như thế: Còn quỉ này

là… hàng – như trong cái ý, Nam Kít nhận họ, Bắc Kít nhận hàng – và bởi

thế,

hàng này mới thật là tuyệt vời, "ơi Thi ơi Thi ơi", một em Bắc Kít

chẳng đã từng

nghe, đến vãi lệ, 1 giọng Nam Kít, phát ra từ cặp loa Akai, tặng

phẩm-chiến lợi phẩm

của cuộc ăn cướp - Bạn ăn cướp và bây giờ bạn phải sử dụng nó, làm cho

nó trở

thành có ích… Trên cây cầu Charles Bridge ở Prague, có một cái bệ,

bên dưới 1 bức tượng thánh,

nó kể câu chuyện của bạn. Vị thánh trầm mình xuống một cánh bùn, kéo

theo với ông

một con quỉ. Lẽ dĩ nhiên, con quỉ đếch hài lòng, và tỏ ra hết sức giận

dữ

(và đây

là ý nghĩa của ẩn dụ, một khi mà con quỉ cuộc chiến Mít chưa hài lòng,

dù có dâng

hết biển đảo cho nó, thì chiến thắng đỉnh cao vưỡn chưa hoàn tất), nó

nhe răng, tính

ngoạm lại sư phụ của nó 1 phát! NYRB Thiên tài Bắc

Đảo và cơn hăm dọa của ông ta, là ở trong cái sự liền lạc, không mối

nối, không

sứt mẻ, nhưng thật là hài hòa, khi thực hiện cuộc hôn nhân giữa ẩn dụ

và chính

trị: ông là 1 chiến sĩ, 1 tên du kích, đúng hơn, trong 1 cuộc chiến đấu

ở mức

ngôn ngữ. Chicago

Tribune

Two

Cities by A

CITIES THAT ARE too beautiful lose their individuality. Some of the southern towns cleaned up for tourists remind one more of glossy photo ads than of organic human settlements. Ugliness creates individuality. Cracow cannot complain of a dearth of infelicitous, heavy, melancholy places. Những thành

phố đẹp quá mất mẹ nó căn cước cá nhân của chúng. Một vài thành phố

phía Nam rửa

ráy làm sạch chúng, để chào đón khách du lịch làm nhớ tới những tấm bưu

thiếp,

những tấm biển quảng cáo hơn là những nơi cư ngụ của bầy đàn con người.

Cái xấu

xí tạo căn cước cá nhân. Cracow chẳng có gì để mà phàn nàn, về những

nơi chốn, địa

điểm không may, bất hạnh, nghèo nàn, dơ dáy, nặng nề, buồn ơi là buồn

của nó. April 15,

2014 5:38 pm ‘Capital in

the Twenty-First Century’, by Thomas Piketty (1) Note: Cuốn

này, đang được thổi dữ lắm. Tác giả là 1 anh Tẩy Capital in

the Twenty-First Century, by Thomas Piketty, translated by Arthur

Goldhammer,

Harvard University Press RRP£29.95/Belknap Press RRP$39.95, 696 pages French

economist Thomas Piketty has written an extraordinarily important book.

Open-minded readers will surely find themselves unable to ignore the

evidence

and arguments he has brought to bear. Capital in

the Twenty-First Century contains four remarkable achievements. First,

in its

scale and sweep it brings us back to the founders of political economy.

Piketty

himself sees economics “as a subdiscipline of the social sciences,

alongside

history, sociology, anthropology, and political science”. The result is

a work

of vast historical scope, grounded in exhaustive fact-based research,

and

suffused with literary references. It is both normative and political.

Piketty

rejects theorising ungrounded in data. He also insists that social

scientists

“must make choices and take stands in regard to specific institutions

and

policies, whether it be the social state, the tax system, or the public

debt”. Second, the

book is built on a 15-year programme of empirical research conducted in

conjunction with other scholars. Its result is a transformation of what

we know

about the evolution of income and wealth (which he calls capital) over

the past

three centuries in leading high-income countries. That makes it an

enthralling

economic, social and political history. Among the

lessons is that there is no general tendency towards greater economic

equality.

Another is that the relatively high degree of equality seen after the

second

world war was partly a result of deliberate policy, especially

progressive

taxation, but even more a result of the destruction of inherited

wealth,

particularly within Europe, between 1914 and 1945. A further lesson is

that we

are slowly recreating the “patrimonial capitalism” – the world

dominated by

inherited wealth – of the late 19th century. Some argue

that rising human capital will reduce the economic significance of

other forms

of wealth. But, notes Piketty, “ ‘nonhuman

capital’ seems almost as indispensable in the twenty-first century as

it was in

the eighteenth or nineteenth”. Others argue that “class

warfare” will give way to “generational

warfare”. But inequality within generations remains vastly greater than

among

them. Yet others suggest that intragenerational mobility robs rising

inequality

of earnings of significance, particularly in the US. This, too, is

false: the

rise in inequality of earnings in the US over recent decades is the

same

however long the period over which earnings are traced. High-school

dropouts

rarely become chairman of GE. An important

finding is that the ratio of wealth to income in Europe has climbed

back above

US levels, notably in France and the UK. Another is the notably big

recent rise

in the income shares of the top 1 per cent in English-speaking

countries (above

all, the US) since 1980. Perhaps the most extraordinary statistic is

that “the

richest 1 percent appropriated 60 percent of the increase in US

national income

between 1977 and 2007.” Technology and globalisation can hardly explain

this,

since both were at work in all high-income countries. In all, the two

most

striking conclusions are the rise of the “supermanager” in the US and

the

return of patrimonial capitalism in Europe. Third,

Piketty uses simple economic models to explain what is going on. He

notes, for

example, that the huge rise in labour earnings at the top of US income

distribution is overwhelmingly explained not by sports stars or

entertainers

but by increases in remuneration of managers. He argues that this is

the result

of the falls in marginal taxation, which have increased the incentive

to

bargain for higher pay, reinforced by changes in social norms. The

alternative

view – that the marginal productivity of top managers has exploded –

is, he

asserts, unpersuasive, partly because the marginal product of a manager

is

unmeasurable and partly because overall economic performance has not

improved

since the 1960s. More

interesting is Piketty’s theory of capitalist accumulation. He argues

that the

ratio of capital to income will rise without limit so long as the rate

of

return is significantly higher than the economy’s rate of growth. This,

he

holds, has normally been the case. The only exceptions from the past

few

centuries are when a sizeable part of the return on wealth is

expropriated or

destroyed, or when an economy has opportunities for exceptionally fast

growth,

as in postwar Europe or the emerging economies today. This theory

is built on two pieces of evidence. One is that the rate of return is

only

modestly affected by the ratio of capital to income. In the language of

economists, the “elasticity of substitution” between capital and labour

is far

greater than one. In the long run, this seems plausible. Indeed, an age

of

robotics might further raise the elasticity. The other is

that, at least in normal times, capitalists save a sufficiently large

share of

their returns to ensure that their capital will grow at least as fast

as the

economy. This is especially likely to be true of the seriously wealthy,

who are

also likely to enjoy the highest returns. Small fortunes are eaten; big

ones

are not. The tendency for capital to grow faster than the economy is

also more

likely when the growth of the economy is relatively slow, either

because of

demographics or because technical progress is weak. Capital-dominated

societies

also have low-growth economies. Fourth,

Piketty makes bold and obviously “unrealistic” policy recommendations.

In

particular, he calls for a return to far higher marginal tax rates on

top

incomes and a progressive global wealth tax. The case for the latter is

that

the reported incomes of the richest are far smaller than their true

economic

incomes (the amount they can consume without reducing their wealth).

The rich

may even take themselves outside any fiscal jurisdiction, so enjoying

the

fiscal position of aristocrats of pre-revolutionary France. This fact

blunts

one of the criticisms of the book’s reliance on pre-tax data: over

time, the

ability of individual countries to redistribute resources towards the

middle

and bottom of national income distributions might dwindle away to

nothing. Yet the book

also has clear weaknesses. The most important is that it does not deal

with why

soaring inequality – while more than adequately demonstrated – matters.

Essentially, Piketty simply assumes that it does. One argument

for inequality is that it is a spur to (or product of) innovation. The

contrary

evidence is clear: contemporary inequality and, above all, inherited

wealth are

unnecessary for this purpose. Another argument is that the product of

just

processes must be just. Yet even if the processes driving inequality

were

themselves just (which is doubtful), this is not the only principle of

distributive justice. Another – to me more plausible – argument against

Piketty’s is that inequality is less important in an economy that is

now 20

times as productive as those of two centuries ago: even the poor enjoy

goods

and services unavailable to the richest a few decades ago. For me the

most convincing argument against the ongoing rise in economic

inequality is

that it is incompatible with true equality as citizens. If, as the

ancient

Athenians believed, participation in public life is a fundamental

aspect of

human self-realisation, huge inequalities cannot but destroy it. In a

society

dominated by wealth, money will buy power. Inequality cannot be

eliminated. It

is inevitable and to a degree even desirable. But, as the Greeks

argued, there

needs to be moderation in all things. We are not seeing moderate rises

in

inequality. We should take notice. Martin Wolf is the FT’s

chief

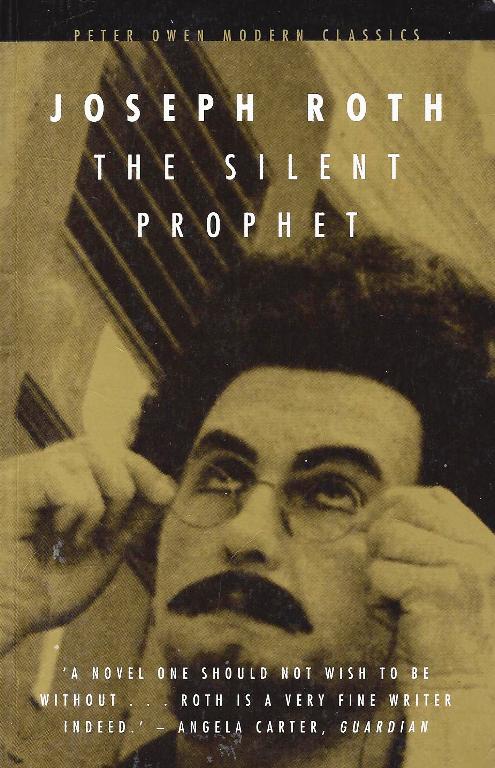

economics commentator  Thánh Văn Cao Với những

độc giả Việt Nam thường quan tâm tới

văn học Việt Nam, và số phận hẩm hiu của những nhà văn An Nam khổ như

chó, nhất

là của những người thuộc nhóm Nhân Văn Giai Phẩm, đặc biệt là Văn Cao:

họ đều

mang bóng dáng những nhân vật của Roth, đều cưu mang những đề tài của

Roth.

Chúng ta cứ tự hỏi, tại sao ông [Roth] không thể đi Mẽo: hãy giả dụ một

ông Văn

Cao di cư vào Nam, và sau đó vượt biên rồi nhập tịch Mẽo, là thấy ngay

sự tiếu

lâm của nó!

On

The Wrong

Side of HistoryĐề tài cuốn Vị Khách Mời Của Trái Đất [Tarbaras, The Guest on Earth], của Roth, thật hợp với Văn Cao, nhưng với rất nhiều khác biệt. Đây là câu chuyện, một ông giết người sau đó trở thành thánh, và vì ông giết người, sau thú tội, và là người độc nhất thú tội, nên mới trở thành thánh!  Joseph Roth: Đường Ra Trận Mùa Này Đẹp Lắm! Về Phía Ngụy Joseph Roth,

như tiểu thuyết gia, là từ báo chí, qua vai ký giả. Tương tự Garcia

Marquez,

nhưng, nếu, với Garcia Marquez, ông phải dựa vào [phịa ra thì cũng

được] cái gọi

là hiện thực huyền ảo, thì Roth có sẵn cả 1 đế quốc Áo Hung, tha hồ mà

tung

hoành. Anh tà lọt Osin không có được cái "vision" này, thành ra mớ hổ

lốn của anh chẳng thể trở thành 1 tác phẩm, về cả hai mặt báo chí lẫn

giả tưởng.

Và, như Gấu phán, cái mà Mít cần, là … giả tưởng, chứ không phải... sự

thực lịch

sử! Một giả tưởng, chẳng cần dài, cỡ Y Sĩ Đồng Quê của Kafka. Viên y sĩ bị

lừa, có ngay ở ngoài đời, là nhà văn DTH. Cảnh DTH ngồi khóc ở hè đường Sài Gòn, thì đâu có khác gì anh y sĩ già ngửa mặt lên trời than, ta bị lừa, bị lừa! Chúng ta cứ

thử tưởng tượng, nếu không có nhân vật… Tường, mà NMG khăng khăng phán,

tớ phịa

ra, thì liệu có Mùa Biển Động? Cả 1 cuộc chiến có thực, với bao nhiêu con người bỏ mạng, và số phận cả 1 đất nước bốn ngàn năm văn hiến biến thành... không, bắt đầu bằng 1 cú ngụy tạo! Sài Gòn Ngày Nào Của Gấu Khí hậu ẩm ướt

trong thế giới tiểu thuyết NDT Những ngày sau này, kể từ ngày quán cà phê La Pagode phải đóng cửa để sửa chữa, chỗ gặp mặt dễ dàng và quen thuộc của một số bạn bè quen thuộc không còn nữa. Cũng không còn trông thấy một bóng dáng gầy ốm, gầy ốm đến nỗi không thể gầy ốm hơn được nữa, lọt thỏm trong chiếc ghế bành thấp và rộng… Như thế, khi

Gấu quen NDT, Quán Chùa vẫn còn những chiếc ghế bành thấp và rộng,

tường nhà

hàng, những bệ bê tông thấp, bạn đang đi trên hè đường, nhảy 1 phát, là

vô bên

trong, và nếu như thế, thì vụ sửa chữa, là để biến nhà hàng thành 1 nơi

an toàn

hơn, sau cú VC đặt mìn nhà hàng nổi Mỹ Cảnh.

|

Cảnh đẹp VN Giới Thiệu Sách, CD Nhã Tập  Art2all Việt Nam Xưa Talawas VN Express Guardian Intel Life Huế Mậu Thân Cali Tháng Tám 2011 Thơ JHV NTK TMT Mùa hè Còn Mãi NCK Trang đặc biệt Tưởng nhớ Thảo Trường Tưởng nhớ Nguyễn Tôn Nhan TTT 2011 Kỷ niệm 100 năm sinh của Milosz War_Pix Requiem TheDigitalJournalist Sebald IN MEMORIAM W. G. SEBALD Hình ảnh chiến tranh Việt Nam của tờ Life Vĩnh Biệt Bông Hồng Đen Blog 360 plus Blog TV Lô cốt trên đê làng Thanh Trì, Sơn Tây |