Man of

action

Perambulatory

Christmas Books, 6th series.

In recent

years, it has been our custom in autumn and early winter to find each

week a neglected

book or curiosity by an established author, purchased from a

second-hand book-shop,

to ward off Christmas gift-book blues.

The price

guide is £5, but we might burgle the piggy bank for an extra quid or

two if the

need arises. All books are bought to be read. First, some remarks.

Second-hand

bookshops have been assumed to be in danger for several years now, with

reason.

New York friends lament the disappearance of neighborhood favorites.

Abebooks

can supply most things at the click of a mouse. Many people find

convenience in

e-books and e-readers, and if they are happy, we're happy too. It makes

us even

happier to report that all the shops we mentioned last year (sixteen)

are still

in business. A book is a book is a book. You cannot own an ebook. It

has no

aesthetic properties: no ornamentation, no weight, no smell; in short,

no character.

It offers no choice between nice-to-handle and that experience's

opposite. It

does not furnish a room.

We began our

perambulations, as usual, in the Charing Cross Road area, London's

book-town.

Cecil Court continues its bijou existence, hosting several specialist

shops,

dedicated to cars, theatre, gambling, etc. It is also home to one of

our

regular haunts: Peter Ellis, at No 18 - rather, our haunt is the

pavement

outside, where stands a barrow with assorted books at modest prices.

Last week,

as the nights began to draw in, we lighted on Days of Contempt by Andre

Malraux, just the kind of

thing we like: something unfamiliar by

someone

familiar. The dedication is unexpected: "To the German comrades,

who

were anxious

for me to make known what they had suffered and what they had upheld".

Malraux (1901-76) was, par excellence, the writer

as man of action (a species in graver danger than the book). He

was a

revolutionary, fought in Spain, served as de Gaulle's Minister of

State, wrote

books on art. As the author of Man's Fate (La

Condition humaine), Malraux would once have been mentioned in the

same

breath as Gide, Mauriac, Sartre, Duras; but his other novels are scarce

now. Days

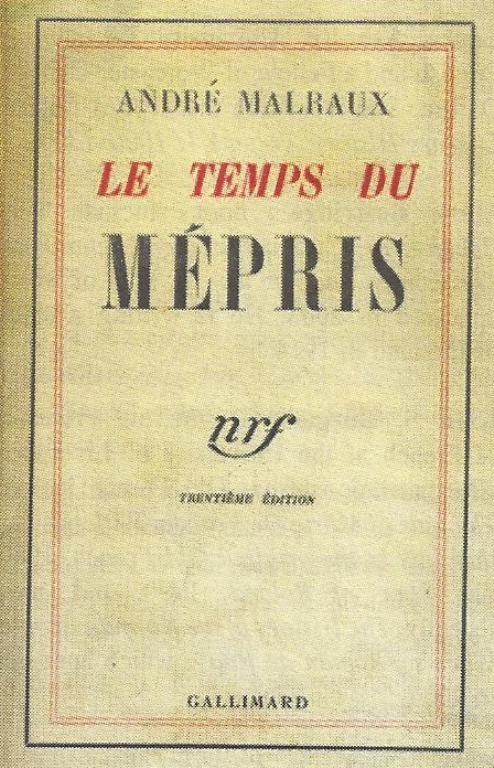

of Contempt (Le Temps du mépris) was written

in 1935, two years after Man's Fate.

The German dedicatees are early

communist victims

of the Nazis. Hitler is mentioned in the second sentence. A comrade,

Kassner,

is about to be interrogated. "Across the table sat the Hitler official.

He

was true to type: heavy jaws, square head, close-cropped hair .... "

Things get

bad for Kassner before they get better. Both he and his creator,

however, believe

they can only get worse for the forces of reaction: "This [Nazi]

government has to reckon with foreign public opinion ... ". It turned

out

not to be that simple.

In 1936, the

TLS described Days of Contempt

(translated by Haakon M. Chevalier) as

"very

short, very simple, very moving", an "epic that deserves high

praise". For our Gollancz Left Book Club Edition, tightly

stitched in

the

usual orange cloth, Peter Ellis charged us £3. We put what was left of

our

budget towards a copy of the original, ordered by post from Cornfield

Books of

Brighton (£5), mainly for the pleasure of displaying the cover. In the

year of

original publication, it had reached its "trentième edition".

Sổ Tay Văn Học

TLS, Oct 5, 2012, đọc lại “Thời Miệt Thị”,

của Malraux, nhân mùa Giáng Sinh năm nay.

Cùng trong Sổ Tay, là 1 entry về những

từ “cà chớn”, trong có từ “asshole”, mà người viết cho rằng, xuất

phát tại

Paris, giữa đám GI, khi Mẽo giải phóng thành phố, do động từ "ngồi" của

Tẩy, s’asseoir”: “asseyez-vous”, mời Ngài ngồi!

Bài này,

theo server, cũng đang "hót":

"Phận Người"

Đà sáng tạo,

creative impetus, của Malraux không chỉ thu gọn vô những cuốn tiểu

thuyết. Nó

còn xùi, suffuse, vô những tiểu luận [GCC thú nhất bài ông viết về

Sanctuary của

Faulkner: Khi Faulkner mang đứa con hư của mình trình làng văn Tây,

André

Malraux phán, đây đúng là, "đưa tiểu thuyết trinh thám vô trong bi kịch

Hy

Lạp", và khi Borges nói dỡn chơi, rằng những tiểu thuyết gia Bắc Mỹ đã

biến

"sự tàn bạo thành đức hạnh", chắc chắn, ông ta có trong đầu lúc đó,

cuốn Giáo Đường của Faulkner. (1)], và những tác phẩm có tính tự thuật,

một số

trong đó – như Phản -Hồi ký, và Những cây sồi mà người ta đốn, Les

Chênes qu’on

abat [Felled Oaks: Chuyện trò với De Gaulle – có sức mạnh cực dẫn dụ,

overwhelming persuasive force, nhờ dòng văn xuôi thần sầu, những câu

chuyện được

kể hớp hồn, và quấn quít trong đó, là những nhân vật được miêu tả, và

họ không

có mặt theo kiểu liệt kê chi tiết, thông báo sự kiện, người thực việc

thực, mà

là những kỳ tích của nghệ thuật dẫn dụ, art of persuasion.

Thử đọc cuộc

lèm bèm giữa Malraux và De Gaulle, trong cuốn chót của bộ sách, ở

Colombey-les-deux-églises, ngày 11 Tháng Chạp 1969. Đúng thứ tiểu sử

của những

vĩ nhân chính trị, mà tôi rất tởm, và nếu 1 ông Tẩy viết ra thì lại

càng tởm,

vì mấy đấng này, lòng ái quốc chỉ thua có mấy anh Mít, cựu thuộc địa

của mấy ảnh,

viết về Bác Hồ!

Tuy nhiên, mặc

dù thiên kiến, lòng dạ đầy thù hằn như thế, vậy mà khi đọc, tôi phải

gật đầu

bái phục: đúng là cuộc nói chuyện giữa "đỉnh với đỉnh", between two

monuments, hai vĩ nhân lèm bèm như là những vĩ nhân trong những cuốn

sách vĩ đại,

who speak as only people in great books speak, với 1 sự đồng điệu, hài

hòa liên

chi, with unremitting coherence, và sáng chói, chúng phá vỡ mọi thiên

kiến, mọi

phòng ngự, thủ thế của tôi, không những thế mà còn làm tôi choáng, vì

cái tôi

huyênh hoang bốc phét, tự cao tự đại khùng điên của nó, và làm cho tôi

tin ở

cái sự cà chớn mang tính tiên tri mà hai vĩ nhân an ủi lẫn nhau, the

prophetic

nonsense with these two brilliant interlocutors consoled themselves:

rằng, nếu

đếch có De Gaulle, Âu Châu tan ra từng mảnh, và nước Pháp, ở trong tay

một lũ

chính trị gia tồi sau De Gaulle sẽ đưa nó xuống đáy địa ngục. Nó dụ

khị, chứ

không phải làm cho tôi tin tưởng, it seduced me, not convinced me, phải

nói như

thế.

Và bây giờ, ở

đây, tôi giải thích, rằng, cuốn Felled

Oaks quả đúng là 1 cuốn “huy hoàng đáng

ghét”, a magnificent detestable book.

Bỗng nhớ...

NMG.

Có lần ông chủ của GCC than, cứ mỗi lần ông cho nhân vật, gáy, lên lớp,

thổ ra

vài thứ triết lý, cách ngôn, minh triết... về phận người, thí dụ,

là cảm thấy ngượng

miệng!

Ui chao Malraux là bậc

thầy của những câu như vậy, Nhưng để nói ra, ông

đòi nhân vật phải “sống bằng cái chết” của nó.

Cả 1 cuốn "Con đường vương

giả", là chỉ để cho Perkin, nhân vật chính, phán, chỉ có mỗi 1 câu:

"Làm

đếch gì có cái

chết, mà chỉ có ta đang

chết"

Nghệ thuật làm dáng