|

1986: Turin AFTER THE SEASON OF AUSCHWITZ Sau Mùa Lò Thiêu Are you

ashamed because you are alive in place of

another? And in particular, of a man more generous, more sensitive,

more

useful, wiser, worthier of living than you? You cannot block out such

feelings:

'you examine yourself, you review your memories, hoping to find them

all, and that

none of them are masked or disguised. No, you find no obvious

transgressions,

you did not usurp anyone's place, you did not beat anyone (but would

you have

had the strength to do so?), you did not accept positions (but none

were offered

to you ... ), you did not steal anyone's bread; nevertheless you cannot

exclude

it. It is no more than a supposition, indeed the shadow of a suspicion:

that

each man is his brother's Cain, that each one of us (but this time I

say us in a much vaster, indeed, universal

sense) has usurped his neighbor's place

and lived in his stead. It is a supposition, but it gnaws at us; it has

nestled

deeply like a woodworm; although unseen from the outside,

it gnaws and rasps. Primo

Levi, from “The Drowned and the Saved”. Khe Sanh,1968 MICHAEL HERR IN A

BLOODSWARM I looked and

there was a pale green horse! Its rider's name was Death, and Hades

followed

with him. Tôi nhìn và

thấy 1 con ngựa xanh nhợt nhạt! Tên kỵ sĩ là Thần Chết, và Diêm Vương,

đằng sau

anh ta. Khe Sanh

1968, Sarajevo 1992, Cõi Khác 1969... là cùng dạng “memoir”, kể cả "Nỗi

Buồn

Chiến Tranh" của Bảo Ninh. Chúng có chung cái air "độc thoại".

Đoạn mở ra Sarajevo, đọc 1 phát là nhập vô liền: There was

spring rain and pale fog in Sarajevo as my plane approached the city

last

April, veering over the green foothills of Mount Igman. Có mưa Xuân và sương mù lợt tạt ở Sarajevo, Tháng Tư vừa rồi, khi chiếc phi cơ của tôi loay hoay chọn hướng đáp xuống thành phố, bên trên những ngọn đồi thấp, màu xanh, của núi Mount Igman. Câu văn còn

làm nhớ câu thơ phổ nhạc của Phạm Duy, “Ngày mai đi nhận xác chồng”,

cái gì gì,

“phi cơ đáp xuống một chiều...” (1) (1) Ngày mai đi

nhận xác chồng Phi cơ đáp

xuống một chiều Bây giờ anh

phủ mầu cờ Em không

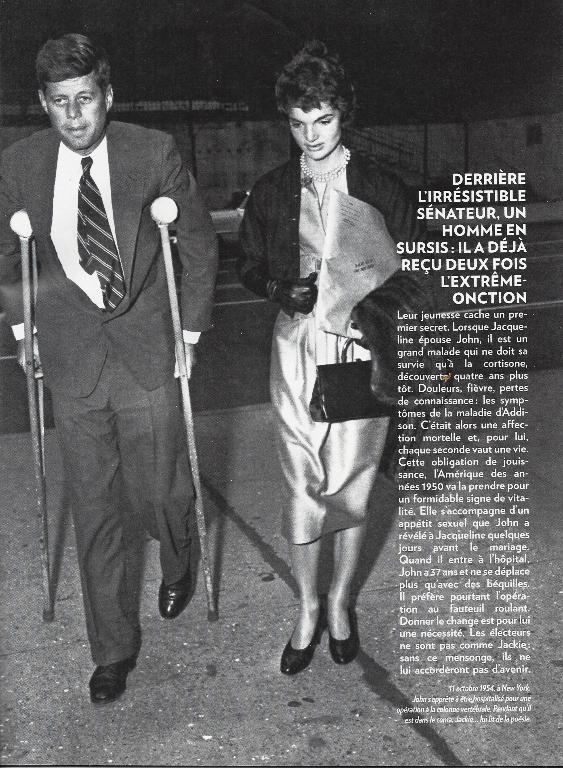

nhìn được xác chàng Lê Thị Ý Đó cũng là lần đầu Gấu biết được mùi thịt chuột, và nó ngon đến cỡ nào, và phải cơ may [“máy trời” xoay chuyển] như thế nào mới được thưởng thức!   Hình Paris

Match, 18-24 Juillet, 2013, số đặc biệt về cặp Kennedy &

Jackie:

Time / 14 May 1973 - You write that 'Ngo Dinh

Diem and his ambitious brother Ngo Dinh Nhu ... were toppled in a 1963

coup that had active US encouragement' [2 April]. Well, perhaps

'toppled' is not so bad a word to choose for 'murdered', though it

would be more accurately applied to the fate of Louis XVI and Charles

I, who certainly lost their 'tops'. (You do not mention a third

brother, the Governor of Hue, who took refuge in the US Consulate and

was handed over by the American authorities to his 'topplers'. The

fourth brother, an archbishop, was, luckily for himself, in Rome,

though President Kennedy might have had scruples in toppling a member

of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Did it ever occur to him that he who

lives by toppling will die by toppling?) Thư này cũng thú. Greene

chửi tờ Time, về cách dùng từ, [nhạy cảm hay không nhạy cảm],

những kẻ “lật đổ” hay là “sát nhân”, trong vụ Mẽo làm thịt mấy anh em

ông Diệm.

Mi viết, xừ Diệm và ông em

tham vọng, Nhu… bị lật đổ trong cú 1963, và cú này được sự khuyến khích

tích cực của Mẽo [báo Time ngày 2 Tháng Tư]. OK. Có lẽ “bị lật

đổ” là 1 từ không đến nỗi tệ, để thay thế từ “bị làm thịt”, nhưng có lẽ

cái từ “tóp, tóp” như thế đó, đúng ra, nên áp dụng cho những trường hợp

của vua Louis 16, và Charles Ðệ Nhất, vì hai xừ này bị chúng chặt mẹ

mất chỗ đội nón, [their tops]! Note: GCC đọc Hitchens,

viết về

Kennedy và cú làm thịt Diệm mới hỡi ơi, về những “biên cương mới”,

“đừng hỏi đất

nước làm gì cho bạn...” Đây chính là câu hỏi mà 40 năm

sau vụ sát hại một tổng thống Mỹ,

tờ Paris Match số đề ngày 16-22 tháng Mười, 2003, bằng một phóng sự đặc

biệt +

hình ảnh, gồm 16 trang, cho biết, một cuộc điều tra của đài Canal+ của

Pháp, và

một cuốn sách, Người Chứng Cuối Cùng, tác giả Billie Sol Estes, nhân

chứng độc

nhất còn sống trong vụ mưu sát, xác nhận: Phó Tổng Thống Mỹ, Johnson,

là người

chủ mưu vụ giết Kennedy. Nguyên nhân: vàng đen Texas. Theo tờ báo, phải luôn luôn

đánh thức lịch sử, đọc đi đọc lại

những trang đen tối nhất của nó, nêu đích danh thủ phạm, cho dù chúng

biến mất

từ đời tám hoánh nào rồi. Hơn nữa, người ta cũng không

thể biện minh cho cái ác, bằng… hậu

quả tốt đẹp của nó. Đây là đề tài của một cuốn tiểu thuyết của G.

Steiner,

trong đó, ông để cho nhân vật giả tưởng của ông là Hitler biện minh

trước lịch

sử: Nếu không có… tui, và vụ Lò Thiêu, làm sao có quốc gia Do

Thái như

hiện nay ? [Liệu sẽ có một ông nào đó,

biện minh: Nếu không có “tội ác..

1975”, làm sao có quốc gia có tên là Thuyền Nhân, hay Việt Kiều Yêu

Nước?]. Tờ Paris Match nêu trên, khi khui lại vụ giết Kennedy, đã lên án cái gọi là dối trá chính trị, theo tờ báo, nó giống như gỉ sắt, làm đắm tầu, làm mất niềm tin của dân chúng. (2) MICHAEL HERR IN A BLOODSWARM (The only Vietnamese many

of us knew was the words "Bao Chi! Bao Chi!" - Journalist!

Journalist!- or even "Bao Chi

Fap!"- French journalist!- which was the same as crying, Don't

shoot!

Don't shoot!)

From Dispatches. The conflict in Vietnam between the communist North and anticommunist South began after the North defeated the French colonial administration in 1954. By 1965 President Johnson had committed over 180,000 US. troops to the country. Herr served six months of active duty in the Army Reserve in 1963 and 1964 and was in Vietnam in the late 1960s as a correspondent for Esquire. In 1977 he published his memoir, Dispatches, which John le Carré called ''the best book I have ever read on men and war in our time. " Mấy từ tiếng Mít độc nhất mà đa số chúng tôi biết, là "Báo chí! Báo chí!", hay, "Báo Chí Pháp", và nó có nghĩa, “Đừng bắn! Đừng bắn!” “Tha mạng cho tôi!” John le Carré

phán, số dách! Tớ chưa từng đọc cái nào bảnh hơn nó, viết về đờn ông và

chiến tranh,

trong cái

thời của chúng ta! Ui chao, giá

mà xừ luý đọc “Tứ Tấu Khúc”, hay “Cõi Khác”, của Gấu Cà Chớn, nhỉ! Đau khổ nhất

là những ngày cô bạn đi lấy chồng. Vẫn những ngày tháng ngây ngô bên mớ

máy

móc, nghe tiếng người nói xôn xao từ những thành phố xa lạ phía bên

ngoài địa

ngục, qua đường dây điện thoại viễn liên, mơ màng tưởng tượng chiến

tranh rồi sẽ

qua đi, cô bạn rồi sẽ hạnh phúc, hạnh phúc... Hết còn nỗi ngây thơ

tưởng mình ở

trên cao, trên tận đỉnh cồn, thấy hết, hiểu hết. Vẫn những đêm dài điên

cuồng

đuổi theo bóng mình sợ hãi trốn sâu dưới đáy địa ngục, trong những hang

cùng

ngõ hẻm thành phố, chạy hoài, chạy hoài, không còn nơi để ghé, không

còn chỗ để

ngừng... Chỉ mong gặp lại những hồn ma quen, những gã phóng viên người

Nhật,

người Mỹ, hai gã chuyên viên Phi Luật Tân, để hỏi coi họ có còn luyến

tiếc đất

nước này hay không, chỉ muốn la lớn, tôi yêu em, tôi yêu em, cho cả thế

giới, cả

loài người đều nghe... |