|

24.11.2016

NYRB Jan, 2000

DECEMBER 27

A Poem for the End of a Thousand Years:

W. H. Auden

We are about to enter the last year of the century and-I was going

to write-of a millennium, but who, in fact, has any sense of the year

999, or for that matter 1132 or 1412? This last century has been more than

enough for us to try to take in. So I found myself thinking about an appropriate

valediction to this last extraordinarily violent hundred years. Sixty

years ago this January, on the eve of the Second World War, the Irish poet

William Butler Yeats died. A younger English poet, W H. Auden, wrote an

elegy for him. It's become a very famous poem. A winter like this one. The

tenth year of an economic depression. Hitler's military, having annexed

Austria and the Sudetenland, is drawing up plans for the conquest of Europe.

And an Irish poet dies:

In Memory of W B. Yeats

(d. Jan 1939)

Robert Hass: Now & Then

For poetry makes nothing happen:

it survives

Bởi là vì thơ đếch

làm cho cái chó gì xẩy ra: nó sống sót

W. H. Auden

A PASSION OF POETS

by Joseph Brodsky

"Time ... worships language and forgives

Everyone by whom it lives ... "

-W. H.AUDEN

I

…..

When a writer resorts to a language other than his mother tongue,

he does so either out of necessity, like Conrad, or because of burning

ambition, like Nabokov, or for the sake of greater estrangement, like

Beckett. Belonging to a different league, in the summer of 1977, in New

York, after living in this country for five years, I purchased in a small

typewriter shop on Sixth Avenue a portable "Lettera 22" and set out to

write (essays, translations, occasionally a poem) in English for a reason

that had very little to do with the above. My sole purpose then, as it

is now, was to find myself in closer proximity to the man whom I considered

the greatest mind of the twentieth century: Wystan Auden.

Khi nhà văn viết, bằng 1 thứ tiếng không phải

tiếng mẹ đẻ, người đó làm như vậy, thì là

do cần thiết, như Conrad, hay, vì một tham vọng nóng

bỏng, như Nabokov, hay, thèm 1 thứ gì ghẻ lạnh hơn, như

Beckett.

Không thưộc băng đảng này, vào mùa

hè năm 1977, ở Nữu Ước, sau khi sống ở Mẽo 5 năm, một bữa, tôi

buồn buồn mua 1 cái máy chữ nhỏ, và khởi sự viết,

bằng tiếng Anh, chỉ với mục đích độc nhất, để cảm thấy mình

gần gụi với người mà tôi nghĩ, cái đầu vĩ đại nhất

của thế kỷ 20: Wystan Auden

Note: Bài viết này, có in trong tập tiểu

luận của Brodsky, Cô Út đem làm từ thiện mất rồi.

Bài trên cuốn Vanity chỉ là trích đoạn.

II

….

If a poet has any obligation toward society, it is to write

well. Being in the minority, he has no other choice. Failing this duty,

he sinks into oblivion. Society, on the other hand, has no obligation

toward the poet. A majority by definition, society thinks of itself as

having other options than reading verses, no matter how well written.

Its failure to do so results in its sinking to that level of locution

by which society falls easy prey to a demagogue or a tyrant. This is

society's equivalent of oblivion; a tyrant, of course, may try to save

his society from it by some spectacular bloodbath.

Nếu nhà thơ có bổn phận với xã hội, thì

đó là, làm thơ hay.

Làm thơ dở như kít, thì đi chỗ khác

chơi!

[Brodsky lịch sự hơn, khi viết, không tròn bổn

phận này, thì chìm vào quyên lãng]

Thuộc thiểu số, hắn không có chọn lựa nào

khác.

Xã hội, về mặt nó, đếch có bổn phận

với nhà thơ. Thuộc đa số, nó có nhiều giải pháp

khác, thay vì đọc thơ, dù thơ hay.

http://tanvien.net/Dayly_Poems/Auden.html

Tưởng niệm Yeats

Nhà thơ biến mất vào

cái chết mùa đông

Những con suối đóng băng, những phi trường gần như bỏ

hoang

Và tuyết huỷ hoại những pho tượng công cộng

Thời tiết chìm vào trong miệng của ngày

chết

Ôi, tất cả những công cụ thì đều đồng ý

Ngày nhà thơ mất đi là một ngày lạnh

giá, âm u.

Thật xa sự bịnh hoạn của ông

Những con chó sói băng qua những khu rừng xanh

rờn

Con sông nơi quê mùa chẳng bị cám dỗ

bởi những bến cảng sang trọng

Bằng những giọng tiếc thương

Cái chết của thi sĩ được tách ra khỏi những bài

thơ của ông.

Nhưng với ông, thì

đây là buổi chiều cuối cùng, như chính ông

Một buổi chiều với những nữ y tá và những tiếng

xầm xì;

Những địa phận trong cơ thể ông nổi loạn

Những quảng trường trong tâm trí ông thì

trống rỗng

Sự im lặng xâm lăng vùng ngoại vi

Dòng cảm nghĩ của ông thất bại: ông trở thành

những người hâm mộ ông

Bây giờ thì ông

phân tán ra giữa hàng trăm đô thị

Với trọn một mớ cảm xúc khác thường;

Tìm hạnh phúc của ông ở trong một cảnh rừng

khác

Bị trừng phạt bởi một luật lệ ngoại về lương tâm.

Nhưng trong cái quan

trọng và tiếng ồn của ngày mai

Khi đám brokers gầm rú như những con thú

ở sàn Chứng Khoán,

Và những người nghèo đau khổ như đã từng

quen với đau khổ,

Và mỗi kẻ, trong thâm tâm của chính

kẻ đó, thì hầu như đều tin tưởng ở sự tự do của nhà

thơ;

Và chừng vài ngàn người sẽ nghĩ về ngày

này

Như 1 kẻ nghĩ về một ngày khi một kẻ nào đó

làm một điều không giống ai, khác lệ thường

Ôi, bao nhiêu công

cụ thì đều đồng ý

Ngày nhà thơ ra đi thì là một ngày

âm u, giá lạnh

II

Bạn thì cũng cà

chớn như chúng tớ: Tài năng thiên bẩm của bạn sẽ

sống sót điều đó, sau cùng;

Nào cao đường minh kính của những mụ giầu có, sự

hóa lão của cơ thể.

Chính bạn; Ái Nhĩ Lan khùng đâm bạn vào

thơ

Bây giờ thì Ái Nhĩ Lan có cơn khùng

của nó, và thời tiết của ẻn thì vưỡn thế

Bởi là vì thơ đếch làm cho cái chó

gì xẩy ra: nó sống sót

Ở trong thung lũng của điều nó nói, khi những tên

thừa hành sẽ chẳng bao giờ muốn lục lọi; nó xuôi về

nam,

Từ những trang trại riêng lẻ và những đau buồn bận rộn

Những thành phố nguyên sơ mà chúng ta tin

tưởng, và chết ở trong đó; nó sống sót,

Như một cách ở đời, một cái miệng.

III

Đất, nhận một vị khách

thật là bảnh

William Yeats bèn nằm yên nghỉ

Hãy để cho những con tầu Ái nhĩ lan nằm nghỉ

Cạn sạch thơ của nó

[Irish vessel, dòng kinh

nguyệt Ái nhĩ lan, theo nghĩa của Trăng Huyết của Minh Ngọc]

Thời gian vốn không khoan

dung

Đối với những con người can đảm và thơ ngây,

Và dửng dưng trong vòng một tuần lễ

Trước cõi trần xinh đẹp,

Thờ phụng ngôn ngữ và

tha thứ

Cho những ai kia, nhờ họ, mà nó sống;

Tha thứ sự hèn nhát và trí trá,

Để vinh quang của nó dưới chân chúng.

Thời gian với nó là

lời bào chữa lạ kỳ

Tha thứ cho Kipling và những quan điểm của ông ta

Và sẽ tha thứ cho… Gấu Cà Chớn

Tha thứ cho nó, vì nó viết bảnh quá!

Trong ác mộng của bóng

tối

Tất cả lũ chó Âu Châu sủa

Và những quốc gia đang sống, đợi,

Mỗi quốc gia bị cầm tù bởi sự thù hận của nó;

Nỗi ô nhục tinh thần

Lộ ra từ mỗi khuôn mặt

Và cả 1 biển thương hại nằm,

Bị khoá cứng, đông lạnh

Ở trong mỗi con mắt

Hãy đi thẳng, bạn thơ

ơi,

Tới tận cùng của đêm đen

Với giọng thơ không kìm kẹp của bạn

Vẫn năn nỉ chúng ta cùng tham dự cuộc chơi

Với cả 1 trại thơ

Làm 1 thứ rượu vang của trù eỏ

Hát sự không thành công của con người

Trong niềm hoan lạc chán chường

Trong sa mạc của con tim

Hãy để cho con suối chữa thương bắt đầu

Trong nhà tù của những ngày của anh ta

Hãy dạy con người tự do làm thế nào ca tụng.

February 1939

W.H. Auden

Cả 1 cõi thơ của Brodsky, là mặc

khải từ bài thơ trên, như David Remnick viết về ông

Cả 1 cõi "viết bằng tiếng Anh" của ông, là chỉ

để thân cận với Auden.

Cũng chỉ là 1 cách tản mạn bên ly cà phê

thôi mà!

Khi được hỏi ông nghĩ gì

về những năm tháng tù đầy, Brodsky nói cuối cùng

ông đã vui với nó. Ông vui với việc đi giầy ủng

và làm việc trong một nông trại tập thể, vui với chuyện

đào xới. Biết rằng mọi người suốt nước Nga hiện cũng đang đào

xới "cứt đái", ông cảm thấy cái gọi là tình

tự dân tộc, tình máu mủ. Ông không nói

giỡn. Buổi chiều ông có thời giờ ngồi làm những bài

thơ "xấu xa", và tự cho mình bị quyến rũ bởi "chủ nghĩa hình

thức trưởng giả" từ những thần tượng của ông. Hai đoạn thơ sau đây

của Auden đã làm ông "ngộ" ra:

Time that is intolerant

Of the brave and innocent,

And indifferent in a week

To a beautiful physique,

Worships language and forgives

Everyone by whom it lives;

Pardons cowardice, conceit,

Lays its honor at their feet.

Thời gian vốn không khoan

dung

Đối với những con người can đảm và thơ ngây,

Và dửng dưng trong vòng một tuần lễ

Trước cõi trần xinh đẹp,

Thờ phụng ngôn ngữ và

tha thứ

Cho những ai kia, nhờ họ, mà nó sống;

Tha thứ sự hèn nhát và trí trá,

Để vinh quang của nó dưới chân chúng.

Auden

Ông bị xúc động

không hẳn bởi cách mà Auden truyền đi sự khôn

ngoan - làm bật nó ra như trong dân ca - nhưng bởi

ngay chính sự khôn ngoan, ý nghĩa này: Ngôn

ngữ là trên hết, xa xưa lưu tồn dai dẳng hơn tất cả mọi điều

khác, ngay cả thời gian cũng phải cúi mình trước nó.

Brodsky coi đây là đề tài cơ bản, trấn ngự của thi

ca của ông, và là nguyên lý trung tâm

của thơ xuôi và sự giảng dạy của ông. Trong cõi

lưu đầy như thế đó, ông không thể tưởng tượng hai mươi

năm sau, khăn đóng, áo choàng, ông bước lên

bục cao nơi Hàn lâm viện Thụy-điển nhận giải Nobel văn chương,

nói về tính độc đáo của văn chương không như

một trò giải trí, một dụng cụ, mà là sự trang

trọng, bề thế xoáy vào tinh thần đạo đức của nhân

loại. Nếu tác phẩm của ông là một thông điệp

đơn giản, đó là điều ông học từ đoạn thơ của Auden:

"Sự chán chường, mỉa mai, dửng dưng mà văn chương bày

tỏ trước nhà nước, tự bản chất phải hiểu như là phản ứng

của cái thường hằng - cái vô cùng - chống lại

cái nhất thời, sự hữu hạn. Một cách ngắn gọn, một khi mà

nhà nước còn tự cho phép can dự vào những công

việc của văn chương, khi đó văn chương có quyền can thiệp vào

những vấn đề của nhà nước. Một hệ thống chính trị, như bất

cứ hệ thống nào nói chung, do định nghĩa, đều là một

hình thức của thời quá khứ muốn áp đặt chính

nó lên hiện tại, và nhiều khi luôn cả tương lai..."

Trước

khi rời nước Nga, Brodsky viết cho Bí thư Đảng Cộng-sản Liên-xô,

Leonid Brezhnev: "Tôi thật cay đắng mà phải rời bỏ nước Nga.

Tôi sinh ra tại đây, trưởng thành tại đây, và

tất cả những gì tôi có trong hồn tôi, tôi

đều nợ từ nó. Một khi không còn là một công

dân Xô-viết, tôi vẫn luôn luôn là

một thi sĩ Nga. Tôi tin rằng tôi sẽ trở về, thi sĩ luôn

luôn trở về, bằng xương thịt hoặc bằng máu huyết trên

trang giấy... Chúng ta cùng bị kết án bởi một điều:

cái chết. Tôi, người đang viết những dòng này

sẽ chết. Còn ông, người đọc chúng, cũng sẽ chết. Tác

phẩm, việc làm của chúng ta sẽ còn lại, tuy không

mãi mãi. Đó là lý do tại sao đừng ai

can thiệp kẻ khác khi kẻ đó đang làm công việc

của anh ta."

Chẳng có gì chứng tỏ Brezhnev đọc thư.

Cũng không có hồi âm.

Six

Poets Hardy to Larkin

W H. Auden

1907-1973

Wystan

Hugh Auden was born in York, brought up in Birmingham, where his

father was a physician, and educated at Gresham's School, Holt, and

Christ Church, Oxford. His student contemporaries included poets Cecil

Day Lewis, Louis MacNeice and Stephen Spender. After graduating in 1929,

he spent several months in Berlin, often in the company of Christopher

Isherwood, his future collaborator. His first book, Poems, was published

in 1930 by T. S. Eliot at Faber and Faber and he later became associated

with Rupert Doone's Group Theatre, for which he wrote several plays,

sometimes in collaboration with Isherwood. In January 1939 the two of

them left England for the United States, where Auden became a citizen

in 1946. His later works include The Age of Anxiety, Nones, The Shield

of Achilles and Homage to Clio, and he also wrote texts for works by Benjamin

Britten and (with Chester Kallman) the libretto for Stravinsky's opera

The Rake's Progress. Elected Professor of Poetry at Oxford in 1956, he

died in Vienna in 1973.

Nobody

in the thirties was quite sure what war would be like, whether there

would be gas, for instance, or aerial bombardment. There's a stock

and rather a silly question: 'Why was there no poetry written in the

Second World War?' One answer is that there was, but it was written

in the ten years before the war started.

Auden was a landscape poet, though of a rather particular kind. The

son of a doctor, he was born in York in 1907 but brought up in Solihull

in the heart of the industrial Midlands. Not the landscape of conventional

poetic inspiration but, for Auden, magical

20.11.2016

Ngo Chi Lan

Vietnamese

15th century

AUTUMN

Sky full

of autumn

earth like crystal

news arrives from a long way off following one wild goose.

The fragrance gone from the ten-foot lotus

by the Heavenly Well.

Beech leaves

fall through the night onto the cold river,

fireflies drift by the bamboo fence.

Summer clothes are too thin.

Suddenly the distant flute stops

and I stand a long time waiting.

Where is Paradise

so that I can mount the phoenix and fly there?

1968, translated with

Nguyen Ngoc Bich

THU

Trời

đầy thu

Đất như pha lê

Tin xa về theo cánh vịt giời

Hương sen bên Giếng Trời

Bèn bỏ đi

Lá sồi

Nhân đêm xuống

Bèn tuồn vô sông lạnh

Đom đóm lập loè nơi giậu tre

Aó hè mỏng quá

Bất thình lình tiếng sáo xa ngưng

Gấu đợi, đợi mãi, thèm nghe lại tiếng sáo

Thiên Đàng ở đâu?

Gấu gõ cửa và khóc ròng

Làm sao mà có được 1 em phượng hoàng

Trèo lên em và bay lên đó?

WINTER

Lighted

brazier

small silver pot

cup of Lofu wine to break the cold of the morning.

The snow

makes it feel colder inside the flimsy screens.

Wind lays morsels of frost on the icy pond.

Inside the curtains

inside her thoughts

a beautiful woman.

The cracks of doors and windows

all pasted over.

One shadowy wish to restore the spring world:

a plum blossom already open on the hill.

1968, translated with

Nguyen Ngoc Bich

SN_GCC_2016

14.11.2016

@ Home from school, 15.5.08

Thu

Toronto 2016, Oct, 16

259

Ba đấng bạn quí sống ở Xề Gòn ngày

nào, đêm qua khuya khoắt ghé thăm Gấu

Cả ba lạ sao cùng tên, bèn làm Gấu

nhớ tới bài thơ của Lý Bạch

"Uống Rượu Một Mình dưới Trăng"

Và Gấu bèn tếu táo làm bài

thơ sau đây:

Trăng tròn như cái chén

Đầy hồng đào

Đầy ba cái tên

Bèn tu một đường tối nay

https://chuyenbangquo.wordpress.com/

Lighting

the lantern

the yellow chrysanthemums

lose their color.

Đèn lồng thắp sáng

những đóa cúc vàng

phai màu

Note:

Theo GCC, dịch không đúng, không làm

bật ra được cái sự chuyển động của bức họa hai ku

Lighting, là danh động tự,

verbal noun.

Phải dịch là "cái

sự thắp sáng đèn

lồng", và chính cái sự thắp đèn này,

làm hoa "mất" màu, không phải "phai" màu,

theo nghĩa thường xẩy ra của hoa.

Hai hiện tượng, thắp đèn

và hoa mất màu "ăn dzơ" [en jeu] với nhau, và xẩy

ra, cái nọ trước cái kia, vẫn theo GCC.

Dịch như trên, chúng ta không thấy

được ảnh hưởng của

ánh sáng đèn lên màu của hoa.

Thường thường ánh sáng tôn cái

đẹp của hoa đẹp, người đẹp.

Bài hai ku cho thấy, ngược lại.

thắp lửa cho đèn lồng

ánh sáng làm những đóa cúc

vàng

bị lấn át sắc màu.

Cám ơn bác Tr. Hồi sáng dịch ba chớp

ba nhoáng để đi làm. Chiều về sửa.

You're welcome

Thơ trên

Tinvan http://www.tanvien.net/

Lighting the lantern

the yellow chrysanthemums

lose their color.

bác guc

dịch (theo ý của Mr.Tinvan):

Thắp đèn

lên

Cúc vàng

nhợt mặt

Thu

Toronto 2016, Oct, 16

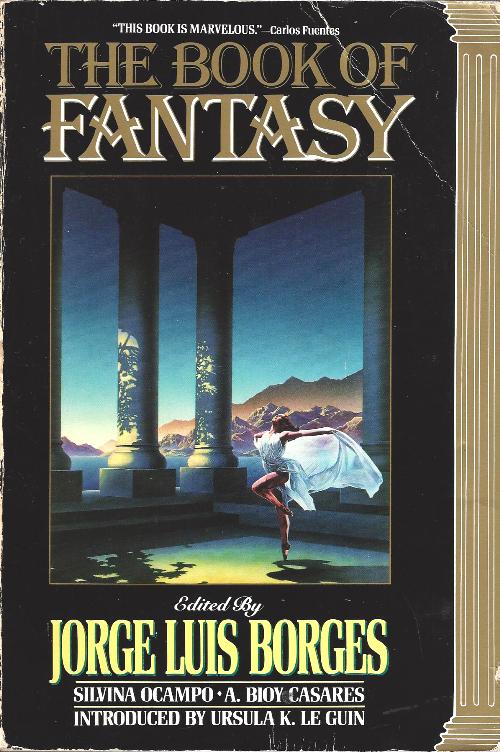

Vô tiệm sách cũ,

vớ được cuốn lạ, Borges biên tập. GCC chưa từng nghe tới cuốn

này! Kafka đóng góp hai truyện, Josephine và

Trước Pháp Luật. Trang Tử, Bướm mơ người hay người mơ bướm.

Một truyện trong cuốn sách.

Bolano có lần cũng khoe, như GCC khoe

vừa rồi.

Trong, có đến mấy truyện là từ Liêu

Trai.

Truyện sau đây, mà chẳng khủng sao?

Ending for a Ghost Story

I. A. Ireland, English savant born in

Hanley in 1871. He claimed descent from the infamous impostor William

H. Ireland, who had invented an ancestor, Wiliam Henrye Irlaunde,

to whom Shakespeare had allegedly bequeathed his manuscripts. He published

A Brief History

of Nightmares

(1899), Spanish Literature (1911),

The Tenth Book of Annals of

Tacitus, newly done into English (1911).

'HOW eerie!' said the girl, advancing

cautiously. And what a heavy door!' She touched it as she spoke and it suddenly

swung to with a click.

'Good Lord!' said the man, 'I don't believe there's

a handle inside. Why, you've locked us both in!' 'Not both of us.

Only one of us,' said the girl, and before his eyes she passed straight

through the door, and vanished.

Note: Truyện ngắn trên,

là từ “The Book of Fantasy”, do Borges biên

tập. Bạn đọc nó, song song với dòng thơ Apollinaire,

“Ouvrez-moi cette porte où je frappe en pleurant”, [“Hãy mở cánh

cửa này, Gấu đập và khóc ròng], và “BHD và GCC”

[A Rose and Milton], thì

mới đã!

Đoạn kết một Truyện Ma

I.A Ireland, một nhà bác

học Anh, sinh tại Hanley, năm 1871. Ông “bốc phét”,

là hậu duệ của tên lừa đảo tai tiếng, William Ireland,

ông này thì đã phịa ra 1 ông tổ,

Wiliam Henrye Irlaunde; Shakespeare đã từng truyền bản thảo cho

ông tổ này.

“Dễ sợ làm

sao”, cô gái nói, dò dẫm bước tới.

“Cái cửa nặng quá!”. Cô sờ vô

cánh cửa trong khi nói, và bất thình

lình, cái cửa chuyển động, cùng 1 tiếng "click".

“Trời ơi là Trời!” Cậu trai nói. “Tôi

không tin có quả đấm ở phía bên trong.

Thế là cô nhốt hai đứa rồi. Tại sao?”

“Đâu phải hai đứa. Chỉ anh thôi”.

Cô gái nói, cùng lúc,

biến mất, qua cánh cửa đóng.

The Man Who Did Not Believe in Miracles

Chu Fu Tze,

who didn't believe in miracles, died; his son-in-law was watching

over him. At dawn the coffin rose up of its own accord and hung noiselessly

in the air, two feet from the ground. The pious son-in-law was terrified.

'Oh venerable father-in-law,' he begged. 'Don't destroy my faith that

miracles are possible.' At that point the coffin descended slowly, and

the son-in-law regained his faith.

-HERBERT A. GILES

Chu Fu Tze không tin vào

phép lạ, chết. Ông con rể ngồi canh xác. Gần

sáng, cái hòm từ từ tự dâng lên

và lơ lửng ở trên không, không gây 1

tiếng động. Ông con rể sợ quá, năn nỉ, Bố ơi Bố, đừng

làm con tin là có phép lạ chứ. Bố cũng

đâu có tin vào mấy trò ma quỉ đó.

Hình như nghe ra, xác ông bố vợ trong chiếc áo

quan bèn từ từ hạ xuống, và ông con rể có lại

niềm tin của mình.

Guilty Eyes

Ah'med Ech Chiruani is a name from

a notebook, from a collection of folk tales. Nothing more is known

of him.

A man bought a girl for the

sum of four thousand denarii. Looking at her one day, he burst into tears.

The girl asked why he wept. He replied: 'Your eyes are so beautiful that

they make me forget to worship God.' Later, when she was alone, the girl

plucked out her eyes. 'Why do you so disfigure yourself? You have devalued

your own worth.' She replied: 'I would not wish any part of me to stop you

worshipping God.' That night, the man dreamed and heard a voice telling

him: 'The girl devalued herself in your eyes, but she increased her value

in ours and we have taken her from you.' When he awoke, he found four thousand

denarii under his pillow. The girl was dead.

THE BOOK OF FANTASY

The Encounter

A tale from the T'ang Dynasty (618-906

a.d.)

Ch'ienniang was the daughter

of Chang Yi, a public official in Hunan province. She had a cousin

named Wang Chu, an intelligent and handsome youth. The two cousins

had grown up together and, since Chang Yi both loved and approved of

the boy, he said he would accept Wang Chu as his son-in-law. Both the

young people heard and marked the promise; she was an only child and

spent all her time with her cousin; their love grew day by day. And

the day came when they were no longer children and their relations grew

intimate. Unfortunately, her father, Chang Yi, was the only person

around who did not notice. One day a young public official asked Chang

Yi for his daughter's hand. The father, heedless or forgetful of his

earlier promise, consented. Ch'ienniang, torn between love and filial

piety, nearly died of grief; the young man fell into such despair that

he resolved to leave the district rather than watch his mistress married

to another man. He invented some pretext or other and told his uncle that

he must go to the capital. When the uncle was unable to dissuade him, he

supplied the youth with funds along with some presents and offered him

a farewell banquet. In a desperate state, Wang Chu did not leave off moaning

throughout the feast and was more than ever determined to go away rather

than persist in a hopeless love affair. The youth embarked one afternoon;

he had sailed only a few miles when night fell. He ordered his sailor to

tie up so that they might rest. But Wang Chu could not fall asleep; some

time around midnight he heard footsteps approaching. He got up and called

out: 'Who is it, walking about at this hour of the night?' 'I, Ch'ienniang,'

came the reply. Surprised and overjoyed he brought her aboard. She told him

that she had hoped and expected to be his wife, that her father had been

unjust, and that she could not resign herself to their separation. She had

also feared that, finding himself alone in a strange land, he might have

been driven to suicide. And so she had defied general disapproval and parental

wrath and had now come to follow him wherever he might go. The happily

re-united pair thereupon continued the journey on to Szechwan. Five years

of happiness passed, and she bore Wang Chu two children. But there was

no news of Ch'ienniang's family and every day she thought of her father.

It was the only cloud in their happy sky. She did not know whether or not

her parents were still alive; and one night she confessed her anxiety to

Wang Chu. Because she was an only daughter she felt guilty of a grave filial

impiety. 'You have the heart of a good daughter and I will stand by you,'

Wang Chu told her. 'Five years have passed and they will no longer be angry

with us. Let us go home.' Ch 'icnniung rejoice .d and they made ready to

go back with their children.

When the ship reached their

native city, Wang Chu told Ch'ienniang: 'We cannot tell in what state of

mind we will find your parents. Let me go on alone to find out.' At sight

of the house, he could feel his heart pounding. Wang Chu saw his father-in-law,

knelt down, made his obeisance, and begged his pardon.

Chang Yi gazed upon him with

amazement and said: 'What are you talking about? For the past five

years, Ch'ienniang has been lying in bed, in a coma. She has not

gotten up once.'

'But I have told you the truth,'

said Wang Chu. 'She is well, and awaits us on board the ship.'

Chang Yi did not know what to think and sent two maids-in-waiting

to see Ch'ienniang. They found her seated aboard ship, beautifully

gowned and radiant; she asked them to convey her fondest greetings

to her parents. Struck with wonder, the maids-in-waiting returned to

the parental house, where Chang Yi's bewilderment increased. Meanwhile,

the sick girl had heard the news, and now seemed freed of her ill. There

was a new light in her eyes. She rose from her bed and dressed in front

of her mirror. Smiling and without a word, she made her way towards the

ship. At the same time, the girl on the ship began walking toward the

house. The two met on the river-bank. There they embraced and the two bodies

merged, so that only one Ch'ienniang remained, as youthful and lovely as

ever. Her parents were overjoyed, but they ordered the servants to keep

quiet, to avoid commentaries. For

more than forty years Wang Chu and Ch'ienniang lived together in happiness.

Eternal Life

James George Frazer British social anthropologist,

born in Glasgow in 1854, died in 1941. His major work is The Golden Bough

(1890-1915), He also wrote The Devil's Advocate: A Plea for Superstition

(1909) and Totemism and Exogamy (1910)

A fourth story, taken down near Oldenburg

in Holstein, tells of a jolly dam that ate and drank and lived right

merrily and had all that heart could desire, and she wished to live

always. For the first hundred years all went well, but after that she

began to shrink and shrivel up, till at last she could neither walk

nor stand nor eat nor drink. But die she could not. At first they fed

her as it she were a little child, but when she grew smaller and smaller

they put her in a glass bottle und hung her up in the church of St Mary,

at Lubeck. She is as small as a mouse, but one a year she stirs

GCC đã dịch mấy truyện ngắn

ma ở trong cuốn này, để lung tung, không làm sao kiếm

thấy nữa!

WAIT

FOR AN AUTUMN DAY

(FROM EKELOF)

Wait for an autumn day, for a slightly

weary sun, for dusty air,

a pale day's weather.

Wait for the maple's rough, brown

leaves,

etched like an old man's hands,

for chestnuts and acorns,

for an evening when you sit in the

garden

with a notebook and the bonfire's smoke contains

the heady taste of ungettable wisdom.

Wait for afternoons shorter than

an athlete's breath,

for a truce among the clouds,

for the silence of trees,

for the moment when you reach absolute

peace

and accept the thought that what you've lost

is gone for good.

Wait for the moment when you might

not

even miss those you loved

who are no more.

Wait for a bright, high day,

for an hour without doubt or pain.

Wait for an autumn day.

Adam Zagajewski: Eternal Enemies

Đợi một ngày thu

[Từ Ekelof]

Đợi một ngày thu, trời mền

mệt, oai oải,

không gian có tí bụi và

tiết trời thì nhợt nhạt

Đợi những chiếc lá phong mầu

nâu, cộc cằn, khắc khổ,

giống như những bàn tay của một người

già,

đợi hạt rẻ, hạt sồi, quả đấu

ngóng một buổi chiều, bạn

ngồi ngoài vuờn

với một cuốn sổ tay và khói từ

đống lửa bay lên

chứa trong nó những lời thánh

hiền bạn không thể nào với lại kịp.

Đợi những buổi chiều cụt thun lủn,

cụt hơn cả hơi thở của một gã điền kinh,

đợi tí hưu chiến giữa những đám

mây,

sự im lặng của cây cối,

đợi khoảnh khắc khi bạn đạt tới sự

bình an tuyệt tối,

và khi đó, bạn đành chấp

nhận,

điều bạn mất đi thì đã mất, một

cách tốt đẹp.

Đợi giây phút một khi

mà bạn chẳng thèm nhớ nhung

ngay cả những người thân yêu ,

đã chẳng còn nữa.

Đợi một ngày sáng,

cao

đợi một giờ đồng hồ chẳng hồ nghi, chẳng đau

đớn.

Đợi một ngày thu (2)

Thu

Toronto 2016, Oct, 16

The End Of Autumn

All of autumn, in the end, is nothing but a cold

infusion. Dead leaves of every sort steep in the rain. No fermentation,

no production of alcohol: we’ll have to wait until spring to judge

the effects of a cold compress on a wooden leg.

Sorting the ballots is a disorderly procedure.

All the doors of the polling place slam open and shut. Throw it

out! Throw it all out! Nature rips up her manuscripts, demolishes

her bookshelves furiously clubs down her last fruit.

Then she abruptly gets up from her work table.

She suddenly seems immense: hatless, head in the fog. Swinging

her arms, she rapturously breathes in the icy, intellectually clarifying

wind. Days are short, night falls fast; there’s no time for comedy.

The earth, in the stratosphere with the other

heavenly bodies, looks serious again. The lit up part is narrower,

encroached on by valleys of shadow. Its shoes, like tramp’s, soak

up water and make music.

In this frog-farm, this salubrious amphibiguity,

everything regains strength, leaps from stone to stone, changes

pasture. Streams proliferate.

This is what’s called a good clean-up, with no

respect for convention! Dressed or naked, soaked to the marrow.

And it doesn’t dry up right away, it goes on and

on. Three months of salutary reflection with no bathrobe, or loofah,

no vascular reaction. But its sturdy constitution resists.

So, when the little buds begin to jut out, they

know what they’re doing, what it’s all about. That’s why they

come out so cautiously, red-faced, benumbed, they know what lies

ahead.

But thereby hangs another tale, perhaps from the

black rule, though it smells different, I’ll now use to draw the

line under this one.

Translated from French by C.K. Williams in Francis

Ponge – Selected

Note: Bài thơ này, chôm trên

net. Tình cờ, thấy trong 1 số báo trên quầy

tại tiệm Indigo, TLS, số Mùa Xuân 2016 (?), cũng

có bài thơ này. Cũng có cái tên

End of Autumn, nhưng ngay câu đầu, là đã khác:

In the end autumn is nothing more than a cup of

tea gone cold.

Sau cùng thu chẳng còn gì,

nếu còn chăng, thì là 1 ly trà lạnh

ngắt

Bèn dùng ipod chôm, từ từ

GCC type, và dịch, song song với bài trên.

Chắc cũng nó.

Trên tờ Điểm Sách của Anh, số mới

nhất, có bài viết về Cuộc tình của Pasternak

với Lara, ở ngoài đời, và là cái mầm

đẻ ra tác phẩm "Bác Sĩ Zhivago".

Cuốn này, không chỉ Xịa, mà còn

có sự trợ giúp của Vatican, mới đưa lén vô được nước

Nga, qua những người đi du lịch.

Nhưng giá trị của nó, cực bảnh,

về mặt văn học, mặc dù tác giả của nó, gần

như phát điên lên: ông nghĩ, ông

được Nobel là nhờ thơ, và đúng ra phải như

thế, theo Milosz, trong bài viết về ông, có trích

đăng trên Tin Văn.

https://literaryreview.co.uk/behind-every-great-book

Boris Pasternak was a larger-than-life

character on the Soviet literary scene. Born at the beginning of

the 1890s into an artistic, successful family of assimilated Jews,

he was much admired by his peers as a poet but clearly fell into the

‘bourgeois’ category disdained by proletarian communists, all the more

so since the rest of his family emigrated after the Russian Revolution.

Stalin, however, thought it worth protecting the man he called a ‘cloud-dweller’.

In the mid-1930s, Pasternak decided to turn to prose, writing a big-canvas

novel set during the Revolution with a protagonist based to some extent

on himself and a love story at its heart. It was published two decades

later as Doctor Zhivago.

A naked chestnut tree that

I saw this afternoon on a walk in Zalla.

It

has been one of the wettest autumns I can remember. Everyday

it rains. I miss the sunlight. And nothing moves me more than

those sharp sunny days of autumn with a light full of contrast and

clarity. I am posting here The end of autumn by Francis Ponge. He

knew how to approach the things of this world, disecting them and opening

them up into new configurations, making us see things afresh:

The End Of Autumn

All of autumn, in the end,

is nothing but a cold infusion. Dead leaves of every sort steep in the

rain. No fermentation, no production of alcohol: we’ll have to wait

until spring to judge the effects of a cold compress on a wooden leg.

Sorting the ballots is a disorderly

procedure. All the doors of the polling place slam open and

shut. Throw it out! Throw it all out! Nature rips up her manuscripts,

demolishes her bookshelves furiously clubs down her last fruit.

Then she abruptly gets up

from her work table. She suddenly seems immense: hatless, head in

the fog. Swinging her arms, she rapturously breathes in the icy, intellectually

clarifying wind. Days are short, night falls fast; there’s

no time for comedy.

The earth, in the stratosphere

with the other heavenly bodies, looks serious again. The lit

up part is narrower, encroached on by valleys of shadow. Its shoes,

like tramp’s, soak up water and make music.

In this frog-farm, this salubrious

amphibiguity, everything regains strength, leaps from stone

to stone, changes pasture. Streams proliferate.

This is what’s called a good

clean-up, with no respect for convention! Dressed or naked,

soaked to the marrow.

And it doesn’t dry up right

away, it goes on and on. Three months of salutary reflection

with no bathrobe, or loofah, no vascular reaction. But its sturdy

constitution resists.

So, when the little buds begin

to jut out, they know what they’re doing, what it’s all about.

That’s why they come out so cautiously, red-faced, benumbed, they

know what lies ahead.

But thereby hangs another

tale, perhaps from the black rule, though it smells different, I’ll

now use to draw the line under this one.

Translated from French by

C.K. Williams in Francis Ponge – Selected

TREES LEAVING

It's so simple watching from the car

the way the leaves get wholly green again.

It's so easy waiting for the rain

that doesn't have to travel very far

to hit us up and bring its discontent

into a low-grade mid-spring afternoon

like Sunday traffic. I remember when

just walking under them was anguish. Then

a livid stem emerging, or a leaf,

was all it took to summon full-fledged grief.

I flowered also, I was full of torment

like spring trees leaving. That was my intent:

to keep it going, being different.

It was who I was and what I meant.

-Jonathan Galassi

NYRB, Oct 17

Thu Toronto 2016, Oct, 16

Ðường Lippincott, Toronto.

Căn nhà bên kia đường, phía trước

mặt, kế bên sân chơi của 1 ngôi trường,

là nơi tạm trú đầu tiên của vợ chồng Gấu.

Thu 2016

AUTUMN

This yardful of the landlord's

used cars

does not intrude. The landlord

himself, does not intrude. He hunches

all day over a swage,

or else is enveloped in the blue flame

of the arc-welding device.

He takes note of me though,

often stopping work to grin

and nod at me through the window. He even

apologizes for parking his logging gear

in my living room.

But we remain friends.

Slowly the days thin, and we

move together towards spring,

towards high water, the jack-salmon,

the sea-run cutthroat.

AUTOMNE

Ce jardin plein des voitures

usagées du proprio

ne me dérange pas. Le proprio

lui-même n'est pas dérangeant. II

reste courbé

toute la journée au-dessus d'un porte-pièces,

ou bien enveloppé par la flamme bleue

de la lampe à souder.

II fait attention à moi pourtant,

s'arrêtant souvent de travailler pour m'adresser

un sourire ou un signe de tête à

travers le carreau.

Il s'excuse

même d'avoir remisé sa tronconneuse

dans ma salle de séjour.

Mais nous restons amis.

Lentement les jours s'allongent, et nous

avancons ensemble vers le printernps,

vers la montée des eaux, le frai des saumons

et la truite anadrome.

Thu

Cái mảnh vườn để xe hơi phế

thải của vì chủ đất không làm phiền tớ

Chính xừ luý thì cũng

thế

Ông ta suốt ngày còng lưng trên

cái máy rập

Hay, lung linh mờ ảo,

Trong làn xanh xanh

Của tia lửa hàn

Tuy nhiên, có tí để ý

Những lần ngưng làm

Để ném cái cười

Hay gật cái đầu

Qua khung cửa sổ

Ông ta lại đi 1 đường xin lỗi nữa chứ

Về việc để bộ đồ nghề

Ở trong phòng khách của chúng

tôi

Nhưng chúng tôi là bạn.

Dần dà, ngày mỏng dần, trải dài

mãi ra

Và Xuân tới

Hai đứa chúng tôi bèn đi tới vùng

nước lớn

Câu cá hồi.

Hai chú hươu đuôi trắng ngắm cảnh thu lộng

lẫy dọc Skyline Drive, Virginia. Ảnh: dherman1145

Autumn Sky

In my great-grandmother's time,

All one needed was a broom

To get to see places

And give the geese a chase in the sky.

•

The stars know everything,

So we try to read their minds.

As distant as they are,

We choose to whisper in their presence.

•

Oh, Cynthia,

Take a clock that has lost its hands

For a ride.

Get me a room at Hotel Eternity

Where Time likes to stop now and then.

•

Come, lovers of dark corners,

The sky says,

And sit in one of my dark corners.

There are tasty little zeros

In the peanut dish tonight.

Charles Simic: New and Selected Poems 1962-2012

Trời Thu

Vào thời bà cố của tôi

Tất cả những gì một người cần

Là 1 cây chổi

Để kiếm chỗ

Và để đuổi

Vịt giời

Những ngôi sao biết hết, biết đủ thứ

Thế là chúng ta bèn cố đọc

Những cái đầu của chúng

Bởi là vì chúng ở quá

xa

Chúng ta chọn cách nói thì

thầm

Dưới sự chứng giám của họ

Ôi BHD của GCC

Hãy lấy cái đồng hồ mất mẹ mấy cây

kim

Làm cái chổi

Đi 1 đường tới Đà Lạt/Thiên Đàng

Lấy cái phòng ở Khách Sạn Thiên

Thu

Nơi Thời Gian thì bèn nghỉ chơi

Lúc này, hay, lúc khác

Hãy tới đây

Những cặp tình nhân của những góc

nhà, hay xó bếp

Bầu trời phán,

Và hãy ngồi, 1 trong những góc

tối của ta

Ở đó có những con số không nho

nhỏ, dễ thèm

Trong cái dĩa đậu phọng tối nay.

LATE SEPTEMBER

The mail truck goes down the

coast

Carrying a single letter.

At the end of a long pier

The bored seagull lifts a leg now and then

And forgets to put it down.

There is a menace in the air

Of tragedies in the making.

Last night you thought you heard

television

In the house next door.

You were sure it was some new

Horror they were reporting,

So you went out to find out.

Barefoot, wearing just shorts.

It was only the sea sounding weary

After so many lifetimes

Of pretending to be rushing off somewhere

And never getting anywhere.

This morning, it felt like Sunday.

The heavens did their part

By casting no shadow along the boardwalk

Or the row of vacant cottages,

Among them a small church

With a dozen gray tombstones huddled close

As if they, too, had the shivers.

Charles Simic: The Voice at 3:00 AM

Tháng Mười Muộn

Xe thư chạy xuống bờ biển

Với chỉ một lá thư

Ở cuối một bến tàu dài

Con hải âu chán đời, nhắc,

hết chân phải lại đến chân trái

Và quên bỏ xuống

Trong không khí có mùi

đe dọa

Về những bi kịch đang thành hình

Đêm qua bạn nghĩ bạn có

nghe tiếng TV

Từ nhà kế bên

Và bạn tin chắc

Về một ghê rợn mới

Họ đang báo cáo

Và thế là bạn bò ra đường để

kiếm

Chân trần, quần xà lỏn

Hóa ra chỉ là tiếng sóng biển

Ưu tư về không biết là bao nhiêu

là đời

Cứ phải giả đò, từ đâu đổ xuống nơi

đây

Và chẳng bao giờ đi bất cứ nơi đâu

Sáng nay, sao giống như

Chủ Nhật

Ông Giời cà chớn chắc là cũng

có góp phần

Trong cái việc, đếch đem một cái bóng

râm nào

Đổ xuống hai bên hè đường

Hay là ở rặng những cái lều trống

trơn

Trong số đó, là 1 ngôi nhà

thờ nhỏ

Với trên chục cái bia mộ bằng đá

Đây

là con phố đầu tiên Gấu biết. Đường College, khu

Phố Tầu Tây, để phân biệt với khu Phố Tầu Đông, mà đa số

người Việt là người Bắc. Gấu quyến luyến với nó

như con voi già, và cái trung tâm

tạm cư, shelter, đầu tiên, ở trong 1 con đường giống như

1 con hẻm, ở đây, nơi gặp lại cô bạn của Cõi

Khác.

http://www.tanvien.net/tgtp_02/michael_ondaatje.html

Ðường Lippincott, Toronto.

Căn nhà bên kia đường, phía trước mặt,

kế bên sân chơi của 1 ngôi trường, là

nơi tạm trú đầu tiên của vợ chồng Gấu.

Gặp lại cô bạn ở đó.

Cô tháo bao tay, bắt tay Gấu tự nhiên như

người Hà Lội, nhưng Gấu lại nhớ đến cái lần cầm

tay đầu tiên, trong 1 rạp chớp bóng Xề Gòn,

khi “sắp sửa” đi lính, [trình diện Trung Tâm

Ba tuyển mộ nhập ngũ Quang Trung], được cô thương tình

nhận lời đi ciné…

Thế là run lên

như… con thằn lằn đứt đuôi

[hình ảnh này chôm của Kiệt, trong Một Chủ Nhật Khác, của TTT, khi

chàng lên cơn sốt, chạy dưới mưa, vô Bưu

Ðiện Ðà Lạt, đánh cái điện cầu cứu

cô học trò Oanh, SOS, SOS!...].

Gấu Cái giận run lên…

Hà, hà!

Căn nhà thuộc 1 cơ sở

từ thiện, chuyên lo tiếp nhận người tị nạn. Có

lần, cũng đã lâu lắm, Gấu có ghé,

đứng bên ngoài nhìn vô, thấy thấp thoáng

mấy người tị nạn vùng Ðông Âu có

thể, tính vô gạ chuyện tào lao, hoặc nếu có

thể đi lên lầu, vô căn phòng ngày nào

chứa vợ chồng Gấu, đúng vào 1 đêm cực lạnh,

sờ vô cái ống sưởi rất xưa, nhưng ngại sao đó,

bèn bỏ đi.

Con phố nhỏ, ăn ra, phía trước mặt

người đàn bà trong hình, con phố College,

một phố chính của downtown Toronto. Có tiệm sách

cũ mà Gấu vẫn thường ghé, từ những ngày đầu

tới thành phố, 1994.

|