|

AA

Complete Poems

Dante II mio bel San Giovanni. Even after his death he did not return * My beautiful San Giovanni VIẾT

MỖI NGÀY / APRIL 19, 2018 : MỘT LỜI

VỀ DANTE Dante

Chàng đếch thèm trở lại Ngay cả sau khi mất Thành phố Hà Lội - Florence - của chàng Rời bỏ, chàng đi thẳng một mách Vì chàng mà tôi hát bài hát này Đêm. Một bó đuốc. Nụ hôn sau cùng. Bên ngoài, âm thanh số mệnh – Như gió hú Từ Địa Ngục, chàng gửi cho nàng một lời trù ẻo. Ở Thiên Đàng, nàng vẫn giữ chàng ở trong đầu Chàng không bước chân trần, muộn trong đêm Bị quyến rũ, như 1 tên tội đồ Qua Hà Lội - Florence - phản bội, đầy hờn oán Thành phố chàng chân thành ao ước

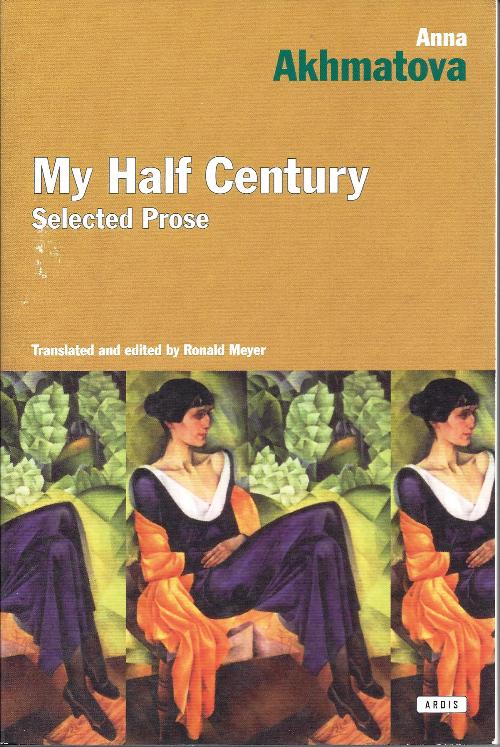

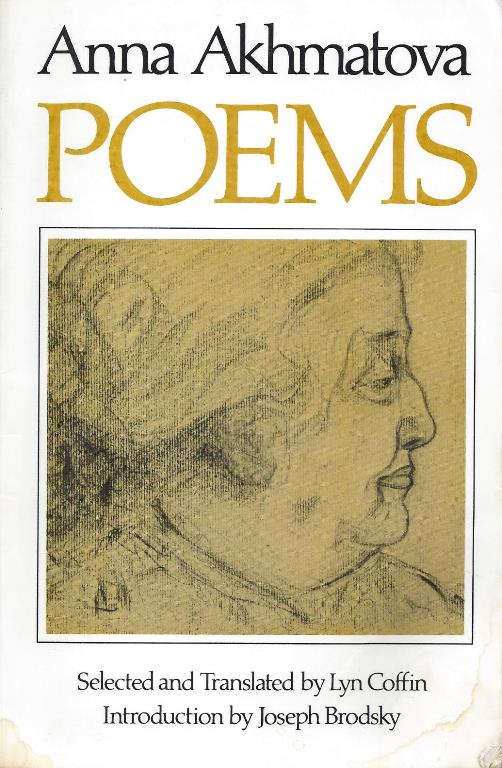

A BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH

And fame carne sailing, like a swan From golden haze unveiled, While you, love, augured all along Despair, and never failed. -From "To My Verses" (1910s) Translated by Walter Arndt ANNA AKHMATOVA BELONGS TO the magnificent quartet of Russian poets whose fellow members are Osip Mandelstam, Boris Pasternak and Marina Tsvetaeva. Like her fellow poets, Akhmatova suffered a bitter fate. Mandelstam died en route to a labor camp (1938); Tsvetaeva hanged herself (1941); Pasternak, ostensibly the "luckiest" of the four, fell victim to a vicious campaign after the publication of Doctor Zhivago, followed by the Nobel Prize for Literature, and in the midst of unbearable pressures died at home in 1960. After the brilliant success of her first books, Akhmatova was forcibly silenced in the mid-1920s and was unable to publish any verse until 1940. But the rehabilitation was short-lived. In August 1946, the Central Committee passed a resolution (rescinded only in 1988) that condemned the "half-nun, half-harlot" Akhmatova, along with Mikhail Zoshchenko, one of the most remarkable satirists of the time. It was only in the 1960s that Akhmatova began to receive the homage due her. AA thuộc bộ tứ thần sầu những nhà thơ Nga, và số phận, cũng bi thảm như họ. Mandelstam chết trên đường tới trại lao động khổ sai. Tsvetaeva treo cổ tự tử. Pat, may mắn nhất, nhưng cũng bị chửi rủa thê thảm nhất, sau khi được Nobel, và chết tại gia. Sau khi nổi tiếng với tập thơ đầu, Bà bị bắt buộc phải im tiếng, giữa thập niên 1920, tới 1940 mới lại được in thơ, nhưng chẳng được lâu. Bà được nhà nước Xô Viết ra hẳn 1 nghị quyết, cấm tiệt in ấn mọi cái viết, sự xuất hiện của con mụ “nửa nữ tu, nửa gái điếm”, và phải đến thập niên 1960 Bà mới được thanh thản. The Hut

I WAS BORN IN THE same year as

Charlie Chaplin, Tolstoy's Kreutzer Sonata, the Eiffel Tower, and, it

seems, T. S. Eliot.' That summer Paris celebrated the one-hundredth

anniversary of the fall of the Bastille-1889. The ancient festival of

St. John's Eve (Midsummer Night) was-and is still-celebrated on the

night of my birth, June 23rd. I was named Anna in honor of my grandmother,

Anna Yegorovna Motovilova.? Her mother, a descendant of Genghis

Khan, was the Tatar princess Akhmatova, whose name I took for

my literary name, not realizing that I was about to become a Russian

poet. I was born in Sara kina's dacha (Bolshoi Fontan, the 11th

railroad stop) near Odessa. This little dacha (more like a hut) was

situated at the bottom of a very narrow and steep tract of land next

to the post office. The seashore there is steep and the railroad tracks

went along the very brink. When I was fifteen years old and we were

living in the dacha at Lustdorf, we were traveling through this area for

some reason, and my mother suggested that we go and see Sarakina's dacha,

which I had never seen. At the hut's entrance I said, "Some day they'll

put up a memorial plaque here." I wasn't being vain. It was just a silly

joke. My mother was distressed. "My God," she said, "how badly I've brought

you up." 1957 Túp Lều

Tôi sinh cùng năm với hề Charlot,

“Kreutzer Sonata” của Tolstoy, Tháp Eiffel, và có thể, T.S. Eliot.

Mùa Hè năm đó Paris kỷ niệm lần thứ 100 phá ngục Bastille – 1889. Lễ hội cổ xưa St. John’s Eve thì vào đêm tôi sinh ra đời, và vẫn là như thế, 23 Tháng Sáu. Tên tôi, là để vinh danh bà ngoại tôi, Anna Yegorovna Motovilova. Mẹ của bà, dòng dõi Hốt Tất Liệt, công chúa Hung Nô, Akhmatova. Tên của bà, tôi lấy làm bút hiệu, không biết rằng thì là mình sẽ trở thành thi sĩ Nga [bà khiêm tốn, đúng ra, trở thành nữ thần thi ca Nga, một nữ thần sầu muộn, như Brodsky vinh danh bà.] Tôi sinh ra tại dacha Sarakina, gần Odessa. Cái dacha này thì cũng chẳng khác chi một túp lều ở cuối 1 dải đất hẹp chạm biển. Bãi biển có bực đi xuống. Khi tôi 15 tuổi, có lần dạo chơi, tới túp lều. Tới lối vô, tôi nói bâng quơ, sau này người ta sẽ khắc 1 tấm biển, ghi lại cái ngày mà tôi tới đây. Mẹ tôi, nhìn tôi, lắc đầu, không biết tao nuôi nấng mi tệ hại ra sao, mà nên nông nỗi này! http://bookhaven.stanford.edu/tag/anna-akhmatova/

Joseph Brodsky on Anna Akhmatova: “Big

gray eyes. Sort of like snow leopards.”

All literature of quality provides the reader with patterns and insights that enable him or her—perhaps not systematically, but frequently enough—to resist false doctrines. Poetry, in particular, is somewhat mysteriously linked to ethics; and poetic discipline to the fortitude of the spirit. Many poets, including Zbigniew Herbert and Akhmatova—and her protégé, Joseph Brodsky—insisted that refusal to succumb to evil is primarily a matter of taste. I was of the same mind. … Mọi văn chương, thứ hảo hạng, cung cấp - có lẽ không hệ thống, nhưng thường xuyên, đủ - cho độc giả những mẫu mã và đốn ngộ khiến anh ta hay chị ả - chống/cưỡng lại những học thuyết dởm. Thơ, đặc biệt, có cái chi bí mật, khiến nó mắc mớ tới đạo hạnh, tới kỷ luật nghiêm ngặt - người xưa thường tắm gội, ăn chay, đếch thèm gần... đờn bà cả tháng, trước khi ngồi vào bàn, làm 1 bài thơ, là do thế, chăng: Rất nhiều nhà thơ, trong có Zbigniew Herbert và Akhmatova – và nhà thơ đàn em của bà, Joseph Brodsky, hằng tâm niệm, rằng, cái sự nói “không” với ma quỉ, với cái ác Bắc Kít – hà, hà, THNM nặng – chủ yếu, là vấn đề của khẩu vị… “insisted that refusal to succumb to evil is primarily a matter of taste.”. Gấu cũng nghĩ như thế! Ui chao, mi nhảm quá! Mĩ là Mẹ của Đạo Hạnh. Brodsky Đẩy lên 1 chút nữa, cái cưỡng lại Cái Ác Bắc Kít, chủ yếu là vấn đề “Khẩu Vị” Thảo nào! Đọc thơ Mít lưu vong cứ ngửi thấy gì không hạp mũi! Note: Cần gì viện dẫn Brodsky. Nguyễn Chí Thiện cũng phán đúng như thế! Short measure get all sentiments in jail, where friendship weighs less than a cigarette, where loyalty, like a report card, spreads thin, where self-respect a spoon of rice knocks down. “Hụt hẫng” - tạm dịch từ ‘short measure’ - có tất cả những tình cảm ở trong tù Nơi tình bạn nhẹ hơn điếu thuốc, Trung thành thì mỏng như tờ tự kiểm, hoặc, báo cáo cán bộ quản giáo Tự trọng thì chỉ cần 1 thìa cháo, là trôi tuột vô họng! At the age of 17, Akhmatova expressed in

a letter her enthusiasm for Symbolist poet Alexander Blok (1880-1921),

in particular for his poem “The Stranger”, which describes a poet whose

muse is a prostitute and who seeks inspiration in a pub: “It’s splendid,

this interlacing of the vulgar commonplace with the divine". Soon,

her poems would gain his attention as well.

One theme entered Blok's poetry was the doom he felt hanging over Russia. In 1918, he wrote a great poem of vision and terror, "The Twelve,” in response to the Russian Revolution. He died at the age of 41 in 1921, exhausted and disillusioned. Critic, literary scholar, and translator Korney Chukovsky described Blok's appearance in May of that year: "I was sitting backstage with him. On stage some ‘orator’ or other… was cheerfully demonstrating to the crowd that as a poet Blok was already dead. 'These verses are just dead rubbish written by a corpse.' Blok leaned over me and said, 'That's true. He's telling the truth, I'm dead.' When Chukovsky him why he did not write poetry any more, Blok always gave the same reply: "All sounds have stopped. Can't you hear that there are no longer any sounds?” Blok had a huge influence on Russian poetry, including schools that were hostile to him… Akhmatova and Mayakovsky learned from him directly. He…. transformed the Russian idiom, and as one of the most controversial and remarkable Russian writers, [was] ‘a monument to the beginning of a century (Anna Akhmatova) Đọc, thì lại nhớ đến cái nick mà Xì ban cho AA: “nửa nữ tu”, “nửa điếm”. Một cách nào, AA thật xứng hợp với nick của Bà, đúng như ý của Bà, khi khen bài thơ của Blok. “Kẻ Lạ”, tả một nhà thơ mà nữ thần thi ca của chàng, là 1 em điếm, và, tìm “yên sĩ phi lý thuần” – inspiration - ở quán đen, hay quán rượu, một hình ảnh tuyệt vời theo AA, do dung tục, thay vì thánh thiện Alexander Blok, ca. 1906

We shall meet again, in Petersburg

Osip Mandelstam https://audiopoetry.wordpress.com/2007/05/31/we-shall-meet-again-in-petersburg/ We shall meet again, in Petersburg, as though we had buried the sun there, and then we shall pronounce for the first time the blessed word with no meaning. In the Soviet night, in the velvet dark, in the black velvet Void, the loved eyes of the blessed women are still singing, flowers are blooming that will never die. The capital hunches like a wild cat, a patrol is stationed on the bridge, a single car rushes past in the dark, snarling, hooting like a cuckoo. For this night I need no pass. I’m not afraid of the sentries. I will pray in the Soviet night for the blessed word with no meaning. A rustling, as in a theater, and a girl suddenly crying out, and the arms of Cypris are weighed down with roses that will never fall. For something to do we warm ourselves at a bonfire, maybe the ages will die away and the loved hands of the blessed women will brush the light ashes together. Somewhere audiences of red flowers exist, and the fat sofas of the loges, and a clockwork officer looking down on the world. Never mind if our candles go out in the velvet, in the black Void. The bowed shoulders of the blessed women are still singing. You’ll never notice the night’s sun. (Translated from the Russian by Clarence Brown and W.S. Merwin) Of all the omissions from our list of poets so far, none is perhaps as surprising to me personally as the absence of Mandelstam. I can’t imagine what I was thinking. Mandelstam, along with Akhmatova and Tsvetaeva, is an old favourite. His poetry has that supra-lyrical quality of transcending understanding – a quality best seen, though in a very different way, in the poetry of Pablo Neruda. I couldn’t explain to you what it is about a poem like this one that I find moving, almost haunting. But something about it speaks to me across time and space, makes me experience a nostalgia for a lost Russian youth that I (obviously) never had. Just the first four lines of this poem are weighted with such sadness, such an intensity of longing, that they alone leave me moved and vulnerable. I particularly love “maybe the ages will die away / and the loved Osip Mandelstam LENINGRAD Russian 1891-1938 I've come back to my city. These

are my own old tears, So you're back. Open wide. Swallow Open your eyes. Do you know

this December day, Petersburg! I don't want to

die yet! Petersburg! I've still got the

addresses: I live on back stairs, and the

bell, And I wait till morning for

guests that I love, Leningrad. December 1930 1972, translated with I returned to my city, familiar

to tears, You have returned here-then

swallow Recognize now the day of December

fog Petersburg, I do not want to

die yet Petersburg, I still have addresses

at which I live on a black stair, and

into my temple And all night long I await the

dear guests, [Osip Mandelstam, Selected Poems, translated by David McDuff. Cambridge: River Press, 1973, p.111] (1) Tôi trở lại thành

phố của tôi, thân quen với những dòng lệ, Hãy nhận ra bây

giờ ngày tháng Chạp mù sương...

Toàn bộ thơ AA. Sách dầy 949 trang The Last Toast

I drink to the ruined house, To the evil of my life, To our shared loneliness And I drink to you- To the lie of lips that betrayed me, To the deadly coldness of the eyes, To the fact that the world is cruel and depraved To the fact that God did not save. June 27, 1934 Couplet

To me, praise from others is - ashes, From you even a reproach is-high praise 1931 Note: Mừng SN/LMH The Muse

When at night I await her coming, It seems that life hangs by a strand. What are honors, what is youth, what is freedom, Compared to that guest with rustic pipe in hand. And she entered. Drawing aside her shawl She gazed attentively at me. I said to her: "Was it you who dictated to Dante The pages of The Inferno?" She replied: "It was I." 1924

THE LAST TOAST I drink to the house, already destroyed, [Trans. by Lyn Coffin] Bữa nhậu chót Mừng trọn đời ta, thật dễ sợ nếu phải kể ra Mừng nỗi cô đơn ta và mi cùng chia sẻ Mừng mi nữa chứ, làm sao không? Mừng đôi mắt lạnh lùng chết người Mừng cặp môi thốt lời dối trá Mừng thế giới quá tàn nhẫn, thô bạo Mừng Ông Trời đếch thèm cứu vớt, và cũng chẳng thèm thử cứu vớt THE MUSE When at night I await the beloved

guest, But now she is here. Tossing aside

her veil, 1924 Nữ Thần Thi Ca Ðêm, ta đợi vị khách quí Nhưng bây giờ, nàng ở đây. Kéo cái

mạng che mặt qua một bên,

Portraits

(To the memory of Akhmatova)

Nothing visits the silence, No apparition of lilac, But an inexplicable lightness I sense when I breathe your name. It's not All Souls'. The planet Spins on without you, Anna. You're now the Modigliani Abstract. No candles flame To amass shadows. Light elected You. Annenkov's portrait ... erect head That tilts with a swan's curve Towards the Neva, towards the living Surge of the iced river That will not stop nor swerve But plunge, if need be, within you ... Till room and time started spinning, I've gazed, I've tried to splinter With love that smiles at stone This photo of nineteen-twenty, The only one where your tender Pure and gamine face, grown One with the page you've entered, Blurs at the lips, half-surrenders A smile ... And your lips open To me, or familiar Chopin ... It must have been a dream. But dreams are something substantial, The Blue Bird, the soft embalmer. It doesn't smell of catacombs There, and your black fringe is no nimbus. A cathedral bell tolls dimly. The unmoving stylus hums. So deep has been this trance, Surely its trace fell once, Caught your eyes and startled you, Between the legendary embankment And your House on the Fontanka? I, like the woman who Had touched the healer's soul, Find everything made whole In your poetry's white night, Envy the poor you kept watch With, outside the prison; the touch Of a carriage-driver, your slight Hands bearing down with a spring, one Moment in the tense of his fingers. Poems outlive a Ming case, But your ageing portraits bring me The rights of a relative To grieve. Tonight alone I could spare All that is written here To restore the chaos where The Neva deranges your hair, You laugh, weep, burn notes, live. D.M. Thomas: Selected Poems Những Bức Chân Dung

(Gửi hồi nhớ của Anna Akhmatova)

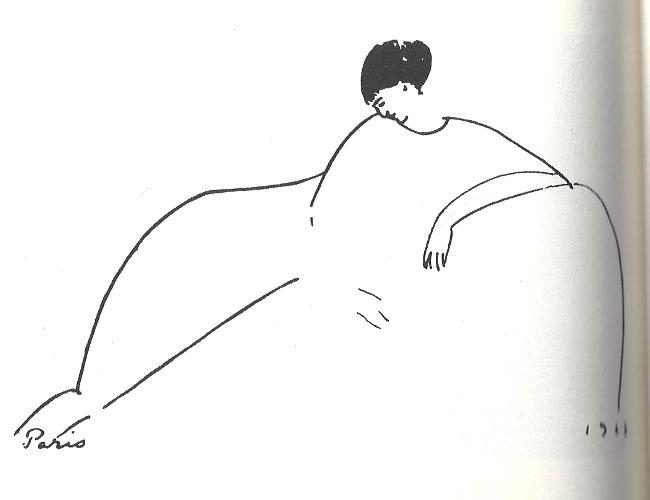

Hư vô thăm

viếng im lặngKhông lilac Nhưng êm ái lạ thường Là điều anh cảm nhận Khi gọi thầm tên em, Như hơi thở Không phải All Souls’ Hành tinh xoay tròn, không có em, Anna. Em bây giờ là Modigliani Trừu tượng Không những ngọn nến Thu gom những cái bóng. Ánh sáng lọc ra em Chân dung Anna… Đầu thẳng đứng Nghiêng xuống đường cong thiên nga Về phía dòng Neva Về những người đang sống Dấy lên từ con sông băng giá Không ngừng chảy, và cũng không lệch hướng Nhưng mà là lao xuống, đâm xuống Nếu cần phải như thế, Ở bên trong em, cùng với em… Cho tới khi căn phòng và thời gian khởi sự xoay xoay, Anh đưa mắt nhìn, Cố làm vỡ òa Bằng tình yêu cười lên đá Bức hình của thế kỷ 19 Bức hình độc nhất em dịu dàng Trong trắng với khuôn mặt của 1 đứa con nít Lớn lên dần với trang sách em nhập vô Nhạt nhòa đôi môi, ngần ngừ cam chịu Một nụ cười…. Và đôi môi mở rộng Với anh, hay Chopin quen thuộc.. Phải là một giấc mơ. Nhưng những giấc mơ là một điều gì có thực, Chim Xanh, Xác Ướp dịu dàng không mùi hầm mộ Ở đó, và cái khăn tua đen của em toả hào quang Chuông nhà thờ tắt dần Tiếng ư ử của 1 cây kim hát vô cảm Cơn hôn mê mới sâu đậm làm sao Có lần trượt đường lăn Đập vô mắt em và làm em giật mình Giữa chuyến lên huyền hoặc Và Căn Nhà của em ở Fontanka? Anh, như người đàn bà Chạm vô linh hồn của người chữa lành Nhận ra, mọi thứ được làm ra, trọn 1 khối Trong đêm trắng của thơ của em Thèm cái nghèo nàn em hằng theo dõi Với, bên ngoài nhà tù; sự đụng chạm với người đánh xe Bàn tay em thon gầy với chiếc nhẫn đè xuống Trong 1 khoảnh khắc Với sức căng của những ngón tay của người đánh xe Những bài thơ sống dai hơn “Ming case” Nhưng những bức chân dung sau này, khi em đã có tuổi Lại mang tới cho anh những quyền hạn của 1 người bà con Để đau buồn Đêm nay, một mình Anh có thể gìn giữ Mọi điều được viết ra ở đây Khi dòng Neva làm tóc em rối tung Em cười, khóc, đốt những dòng ghi chú, và sống. Note: Bài thơ này, có những chi tiết, sự kiện biến thành điển cố, giai thoại, khiến, thật khó dịch, vì, ít ra, phải có chút hiểu biết về cuộc đời của Anna Akhmatova. Sau đây là ghi chú của D.M. Thomas về bài thơ: p.93 Portraits. Anna Akhmatova (1889-1966) survived the Stalinist Terror, during which her son was arrested and sent to Siberia. The portrait by Modigliani was painted when she visited Paris before the First World War. The form of my poem echoes the metre of the major work of her later years, Poem Without a Hero. AA sống sót Thời Kỳ Khủng Bố của Xì, trong thời kỳ đó con trai của Bà bị bắt và đầy đi Siberia. Chân dung của Bà, được Modigliani vẽ, thời gian bà thăm viếng Paris trước Đệ Nhất Thế Chiến. Thể dạng của bài thơ của tôi làm vọng lên "nhịp, phách" của bài thơ lớn của bà, những năm sau này, Poem Without a Hero.

"Why are

you pale, what makes you reckless?"

- Because I have made my loved one drunk with an astringent sadness. I'll never forget. He went out, reeling; his mouth was twisted, desolate. . . I ran downstairs, not touching the banisters, and followed him as far as the gate. And shouted, choking: "I meant it all in fun. Don't leave me, or I'll die of pain." He smiled at me - oh so calmly, terribly -- and said: "Why don't you get out of the rain?" Anna Akhmatova

Anna Akhmatova with Boris Pasternak just after he began writing Doctor Zhivago, 1946 I WRUNG MY HANDS I wrung my hands under my dark

veil ... I'll never forget. He went out,

reeling; And shouted, choking: "I meant

it all ANNA AKHMATOVA translated by Max Hayward

and Stanley Kunitz Tôi vặn

tay tôi,

dưới chiếc khăn choàng màu tối Tôi vặn tay tôi, dưới chiếc

khăn choàng màu tối…

|