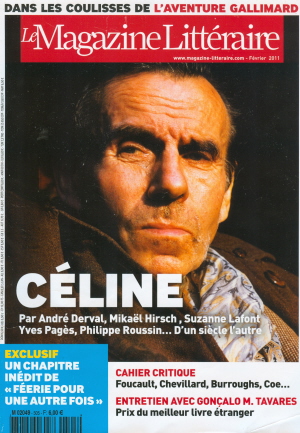

Cat Man |

GEORGE

STEINER Celine LETTERS Edited by

Henri Godard and Jean-Paul Louis 2,034pp.

Gallimard. €66.50. 978207011604 I Le Grand Macabre

The constant

voice of a pivotal writer in the history of the modern novel, who pours

out

inhuman tracts Once again,

it is Celine's hour. As it was in the winter of 1932-3 when the Journey to the End of the Night exploded

- there is no other word - altering crucial aspects of the French

language and

of the compass of fiction in Western literatures. Books by and about

Celine

crowd the displays of Parisian bookstores. Re-editions, paperback

versions

teem. Reportedly, Sartre, whom Celine loathed for his political

opportunism and

second-hand philosophy and whom he savaged in À l'Agité du

bocal in 1945, declared not long before his own death,

"only one of us will endure: Celine". A verdict to be enlarged and

qualified by the realization, now a banality, that two bodies of work

lead into

the idiom and sensibility of twentieth-century narrative: that of

Celine and

that of Proust. Ceine

professed contempt for Proust's "Franco- Yiddish", for his involutes

syntax and homosexual mendacities. He is "the Homer of the perverts".

In a letter to Lucien Combelle on February 12, 1943, Celine defines

Proust's

style as Talmudic: "Le Talmud est à peu près bâti, concu comme les

romans

de Proust, tortueux, arabescoide, mozaique desordonnée - ... Mais au

fond

infiniment tendancieux, passionnement, acharnément .... enrobage des

élites

pourries, nobiliaires, mondaines, inverties . . . en vue de leur

massacre. Epuration" (note the barbed punning

on "arab", on "Mosaic", and the use of epuration two years

before that term was to assume its murderous connotations). Celine

makes one

concession only: Proust's

rendition of his grandmother, réussi

and justly marvelled at by "all Aryan critics". Celine senses that

the Recherche is his only true rival.

But as he informs Claude Gallimard (November 3, 1952), it is he,

Celine, and

not Proust who has inspired Joyce, Faulkner, Henry Miller, Jean Genet

and

lesser fry. All of "Midnight's children" were to be his. In his

invaluable Dictionnaire Celine

(2004), Philippe Alméras lists twenty-seven different lives in one

protagonist.

Many of these have been studied and recounted. From the outset,

Louis-Ferdinand

Auguste Destouches is a traveler. The schoolboy visits England and

learns

English in which he will write letters. He is sent to Germany and

acquires a

halting familiarity with the the language. Conscripted in 1912, marechal de logis and cavalryman Destouches

is an unsparing witness to the ensuing catastrophe: "II y a

une quantité énorme de viande et de sang répandu qui prête reflexions

amères". He is mesmerized by what he foresees as "the agony of the

German empire" and by the hell of combat. The severe wound that Celine

suffers on October 27, 1914, will affect him for life. Henceforth,

decorated

and partly maimed, he will define himself as a victim, invalidated in

body and

soul. Both the French nation and homicidal mankind owe him reparation.

Women,

beginning with the nurses in the army hospitals, are destined to look

after

him, to be pliant to his needs. In these, the erotic plays a complex

but often

marginal part. Disgust at those who elude military service, at

profiteers and

patriotic politicians, is boundless. The first

"Celine" dicta begin to surface. 'J’ai horreur des Noirs";

"Certain beings are predestined to be slaves". Though outwardly

victorious, France faces a diminished and corrupt future. Having

studied

infectious diseases and public hygiene, qualifications that will lead

to a

distinguished thesis on Semmelweis, Destouches, as he still names

himself,

spends several years in French Equatorial Africa. His medical

activities

alternate with the supervision of cocoa plantations. His experiences

and the

letters in which he reports them are similar to those of Rimbaud in

Ethiopia.

The years that follow find Dr Destouches studying problems of public

health on

behalf of the League of Nations, missions which take him to Geneva and

the

United States, where he falls in love with Elizabeth Craig, the first

of many

dancers who will people his volcanic career. Women and ballet come to

crystallize Celine's ideal of lightness within action, within meaning.

If there

is a conventional bite of anti-Semitism in a letter of late October

1916 -

French literature is sentenced to being Jewish, which is to say

"morbid,

mercantile, hysterically patriotic" - there is at the same time an

attach ment

to the philosophy of Bergson. Far more emphatic is Celine's professed

detestation of marriage, his strident resolve to be alone. Before long

he was at work on Voyage au bout de la nuit. Composition most probably

can be

dated as from the end of December 1929. Gallimard’s rejection of the

manuscript,

an editorial howler ironically parallel to its initial rejection of

Proust, and

the last minute failure of the leviathan to obtain the Prix Goncourt,

confirm

Celine's darkening misanthropy. "I rejoice only in the grotesque and at

the frontiers of Death." But his certitude as to the stature and future

of

his book lever wavers. It is "une oeuvre sans pareille" and "the

great fresco of lyric populism" beyond anything in Zola. Its very

punctuation,

those famous dashes and exclamation marks, constitutes a revolutionary

act.

Sales, moreover, were mountainous. Here, also,

Celine's clairvoyance is almost eerie. As early as April 1933, he

predicted that

Hitler would come to dominate Europe. 'Tomorrow all Europe will be

fascist and

Céline will be imprisoned." The prophecies become more graphic after a

visit to Berlin: “Il se prépare là-bas (et pour ici) d'autres

infections,

d'autres immondes diversions sadiques monstrueuses. Des peuples entiers

affamés

et masochistes". In order to prevail, Hitler would have to invade the

Ukraine. This in 1935. What Western statesman or political scientist,

what

Churchill or what Keynes displayed any comparable foresight? Céline's

comments

are like reasoned hallucinations. His insights into the "opaque

sloth" and terminal pathology of the European spirit remain haunting.

Glints of anti-Semitism persist, but are as yet fitful. It was

during 1936, after Celine had found the USSR to be "an ignoble bluff',

that his Jew hatred became obsessive and nauseating. The Jews are

infecting the

world and will be victorious everywhere. New York is nothing but a

ghetto fuelled

by their plutocracy. Zola ,vas an Italian Jew in the pay of the Dreyfusards. Celine now begins spitting

out his loathsome "pamphlets" which are in fact interminable tracts

denouncing all Jews. It is they who brought on, and profited from, the

First World

War and the Bolshevik infamy. It is the Jews whose international

intrigues will

renew Armageddon and prevent that Franco-German entente which aone

could

safeguard Europe. "I am writing an abominably anti-Semitic book": Bagatelles pour un massacre. After which

there will be L'École des cadavres and

Beaux Draps. Quotation from any of these screeds is sickening. They

are the

pornography of hatred. Philippe

Sollers, who has been writing enthusiastically about Celine since 1963,

knows

that these texts are "à la mesure, verbalement" of the mass murder

they invoke and will help generate. He poses the bewildering question:

how are

we to grasp the fact that Celine's deranged racism did not negate his

literary

genius? How can it be that Celine's nihilism "sous sa forme de

passionnalité

vociférante antisemite" produced masterpieces? A contradiction which a

case such as Ezra Pound's cracker-barrel attacks on Jews does not

parallel

(ugly and infantile as these are). The sources

of Celine's mania remain somewhat obscure. Memories of his wartime

anguish had

become cancerous. The Jews were self-evidently implicated, an appalling

irony,

in the possibilities of a recurrent horror. "Rather Hitler than Blum"

was a slogan and sentiment shared by numerous Frenchmen. The descent of

Western

values into frenzied financial speculations, the adulation of the pure

and

applied sciences, the salient role of Jewish messianic instincts in

Marxist

socialism (some of whose therapeutic ideals he actually shared), warped

Celine's judgment still further. But even this witches' brew falls

short of an explanation.

The demonic derangement reaches deeper: "le fanatisme juif est total et

nous condamne à une mort d'espèce atroce, personnellement et

poétiquement

totale". Celine has come to abominate the human species. La

juiverie is not the bottom line:

"l'homme suffit!". But the

inextinguishable Jew somehow embodies the contagious vitality, the

pandemic of

the human species as a whole. As the acid witticism has it: "the Jew is

like other men but more so" (there will be echoes of this reading in

Sartre's essay on the Jewish question). Thus extermination may be the

only

logical conclusion. Celine's

conduct during the Occupation was characteristically idiosyncratic. He

authorized the publication and reissue of his infamous tomes. Together

with

other literary collaborators he accepted an official invitation to

Berlin in

March 1942. His monomania worsened: Racine's plays Bérenice,

Esther and Athalie

are nothing but a "vehement apologia for la Juiverie".

Stendhal is manifestly a Jewish freemason.

Marx's Jadishness is preferable to Montaigne's (who may, possibly, have

had marranos antecedents). Even Maurras

turns out to be a crypto-Jew. Celine informs the fascist leader Doriot

that

Jews must be swept away like faeces. Simultaneously, Celine took no

part in

German-commandeered cultural displays or propaganda, and voiced private

disgust

at the fate of individual Jews and résistants

(who had quarters, of which he was perfectly aware, in his own

apartment

building). These

antinomies climaxed in a scene which, if true, almost defies

imagination. At a

soiree in the German legation, he leaps to his feet and performs a

dazzling

imitation of the Fuhrer's voice and gestures, and instructs his

terrified hosts

that Hitler will lose the war because he is not anti-Semitic enough!

The

assembled dignitaries are said to have scattered in panic. This episode

exactly

counterpoints the grand macabre of Simone Weil's refusal of Catholic

baptism

because the Church of Rome was "still too Jewish". Celine and

his wife fled Paris on June 17, 1944. After a spell at Petain's phantom

court

in Sigmaringen, they made their way through the charred apocalypse of

the

collapsing Reich, reaching Denmark in March 1945. The years there

proved

purgatorial. Celine's spell in prison was harsh, as were the

psychological and

material constraints during his enforced exile on the Baltic coast. At

every

stage, Celine fought like a cornered wild cat against the persistent

threat of

extradition to France where he had been sentenced in absentee and

would, he was

certain, have been executed like Brasillach or assassinated like his

fascist

publisher, Robert Denoel. Celine raged against the suppression of his

writings

and would-be piratical publishers. He sought to refute the howling

testimony of

his detractors. He denied any involvement in Nazi atrocities, and even

strove

to obscure his anti-Semitism. Gangsters, profiteers, masters of

ambiguity such

as Gide and Sartre were flourishing while he, Celine, infirm, gagged

and near

destitution, was being made it scapegoat for France's hypocritical

attempts to

lie its way out of defeat and self-betrayal. The Lettres

de prison and the Lettres des annees noires

display

Celine's rhetoric at its most resourceful. Efforts at rehabilitation

began as

early as 1948. Very gradually, Celine's name could be mentioned without

automatic anathema. More or less covertly, some of his writings inched

their

way back into circulation. Amnesty came in April 1951. By July, the

Celines

were back in France. Now began the fierce struggle against continued

ostracism,

against the silence of retribution that stifled Celine's writings. His

demands

for republication, for objective critical recognition, became

clamorous. In

1956, the walls began to come down. The Voyage was issued in paperback,

proving

to be a revelation to younger readers and would-be imitators. Gallimard

announced that the Voyage and Mort a

credit would enter the Pleiade, a

consecration for which Celine had striven tirelessly. His status as a

"classic" was in sight. It was

during these bitter years that Celine, isolated in Meudon, largely

sequestered

by contempt and organized oblivion, produced a trilogy of fact-fictions

which

towers in modern literature. D'un Chateau

l'autre, Nord and Rigodon match,

if they do not surpass,

the force, the stylistic mastery of the Voyage.

They contain scenes which, using the word with care can be qualified as

"Shakespearean".

Too deaf to hear the approaching RAF fighter, Petain strides along on

his morning

constitutional with seeming heroism and sovereign indifference to

danger. The

sleazy buffoons of his retinue, aware of the swooping plane, do not

know

whether they should scatter for their lives. We are in the realm of

Falstaff,

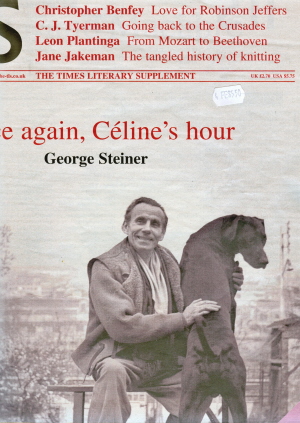

though darkened. Bébert, surely the most famous cat in

twentieth-century

letters, leaps from the northbound train in terror. The entire horizon

is that

of a city in flames. Celine bounds after his beloved pet, desperate for

rescue.

The episode rivals Dante's Inferno,

albeit with a touch of tenderness. Sollers entitles Celine "a

specialist

of Hell", one who in his own words knew death to be his "permanent

mental horizon". Rigodon is the

name of a quick-step dance, popular in the Baroque. Here Celine aims to

enact

that lightness and adroit elegance which had always drawn him to

ballet. The old

Celine still hisses. Gallimard is "a ghetto of pédégaulloresistants".

He wishes to hear more about the negationnistes, the

deniers of the

Holocaust. The politics, the editorial practices, the books being

produced

around him are mostly garbage. But he is now confident that history

will place

him "between Rabelais and Dostoevsky". Celine completed Rigodon

on the very eve of his death on

July 1, 1961. A major part

of Celine's correspondence has already been available. It includes his

letters

to the Nouvelle Revue Francaise and

his loyal supporter there, Roger Nimier, to his cherished translator

Marie

Canavaggia; to Albert Paraz, to Lucien Rebatet, to his lawyers in

Denmark and

France. Further letters have appeared in various memoires

and cahiers. The

Pleiade selection features all the editorial annotations and chrogical

material

emblematic of that monumentalizing imprint. Such voluminous erudition

would

both have exasperated and flattered Celine. His views on literary

scholarship were

less than amicable. The principles of inclusion are not altogether

clear when

so much has been previously published though often in truncated

versions.

Unlike Flaubert or Proust, Celine did not make works of art of his

letters. He

writes them as he breathes. The constant is his voice: argotic, raging,

derisive, imperious, and sometimes strangely gentle. As the editors

note, this

gentleness emerges most distinctly in the letters to the three most

important

women in his life. What takes shape across the 2,000 pages of this

collection

is a biography in motion, an inventory - both fascinating and repellent

- of

"works and days". Nevertheless,

the obvious dilemma persists. Dr Destouches was a caring physician

devoted to

the poorest, most infirm of his patients. His love of animals, strays

included

became legend. Celine's Jew-hatred is monstrous. Indistinct analogies

lie to

hand Wagner's racism, Proust's resort to sadistic, voyeurism,

Heidegger's

engagement with Nazism, Sartre's mendacities in respect of Stalin and

Mao. Aesthetic,

philosophic eminence is no guarantor of humane liberalism. The Celine

case

differs. Here is a writer of decisive stature, pivotal in the history

of the

modern novel, who pours out inhuman tracts. These are couched in an

idiom whose

yawping vulgarity, whose infantile, scatological filth make quotation

emetic.

Inferences of some mode of schizophrenia are facile. At some level the

same

magma is churning in the dynamics of Voyage

au bout de la nuit and of Nord as

in the Bagatelles. The man of

incensed compassion summons the butcher. What memories begot this

amalgam?

"Je n'oublie pas. Mon délire part de là." The Celine

case is, I believe, a singularity (Praise be.) TLS Feb 12, 2010

|