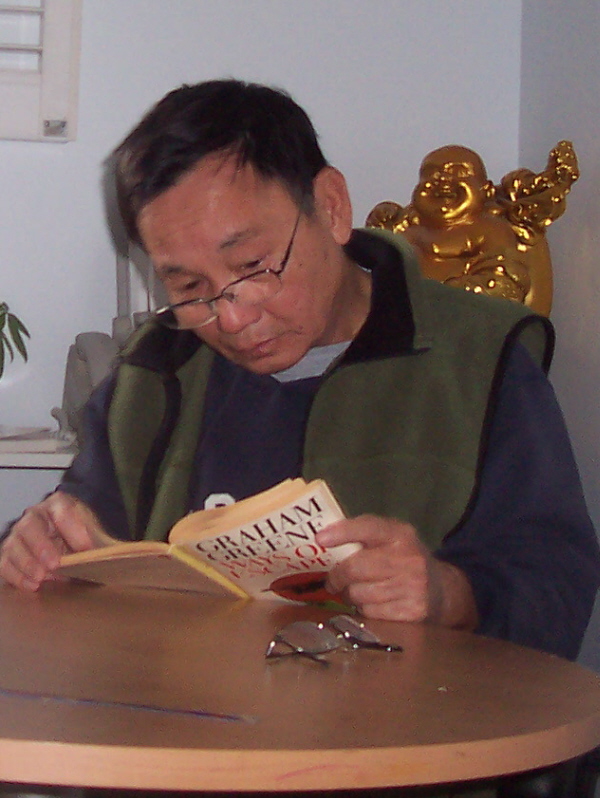

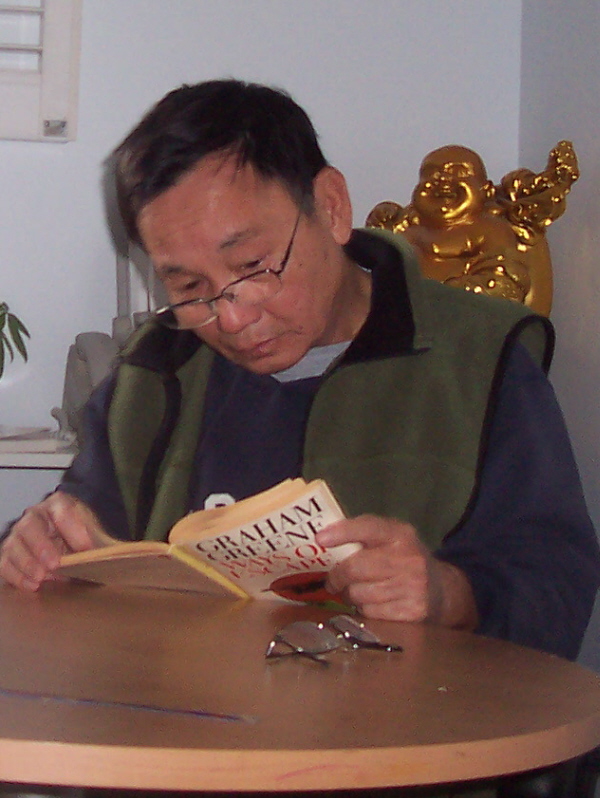

Ui chao, đọc lại

cái đoạn nhật ký của Greene, về những ngày đầu làm quen Cô Ba, mới thấy

sướng

làm sao! Gấu post lại ở đây, để gợi hứng, viết ra những kỷ niệm của

Gấu, về

những ngày đầu, về những bạn bè cùng vướng vào cái thú đau thương này.

Cũng là

một cách tự thú trước “tòa án lịch sử”, về “nghi án”, “có mấy NQT”.

Tiếp theo liền những trang nhật ký viết về Cô Ba, Greene bắt qua trận

đánh Điện

Biên Phủ, với những nhận định thật hách về trận đánh này:

There remains another memory which I find it difficult to dispel, the

doom-laden twenty-fours I spent in Dien Bien Phu in January 1954. Nine

years later when I was

asked by the Sunday Times to write on ‘a decisive battle of my

choice',

it was Dien Bien Phu

that came straightway to my mind.

Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World - Sir Edward

Creasy gave that

classic title to his book in 1851, but it is doubtful whether any

battle listed

there was more decisive than Dien

Bien Phu in 1954. Even Sedan, which came too

late for

Creasy, was only an episode in Franco-German relations, decisive for

the moment

in a provincial dispute, but the decision was to be reversed in 1918,

and that

decision again in 1940.

Dien Bien Phu,

however, was a defeat for more than the French army. The battle marked

virtually the end of any hope the Western Powers might have entertained

that

they could dominate the East. The French with Cartesian clarity

accepted the

verdict. So, too, to a lesser extent, did the British: the independence

of

Malaya, whether the Malays like to think it or not, was won for them

when the

Communist forces of General Giap, an ex-geography professor of Hanoi

University, defeated the forces of General Navarre, ex-cavalry officer,

ex-Deuxieme Bureau chief, at Dien Bien Phu. (That young Americans were

still to

die in Vietnam

only shows that it takes time for the echoes even of a total defeat to

encircle

the globe.)

Điện Biên Phủ không chỉ là hồi chuông báo tử cho quân đội Pháp, mà còn

hơn thế

nhiều! Nó đánh dấu chấm hết mọi hy vọng ăn cướp của Tây Phương đối với

Đông

Phương! Chín năm sau trận đánh, khi tờ Thời Báo Chủ Nhật gợi ý,

tôi nghĩ

liền đến trận đánh thần sầu này.

Võ tướng quân đọc mà chẳng sướng mê tơi sao?

*

31

December 1953. Saigon

One of the interests of far

places is 'the friend of friends': some

quality has

attracted somebody you know, will it also attract yourself? This

evening such a

one came to see me, a naval doctor. After a whisky in my room, I drove

round Saigon with him, on

the back of his motorcycle, to a couple of opium fumeries. The first

was a

cheap one, on the first floor over a tiny school where pupils were

prepared for

'le certificat et le brevet'. The proprietor was smoking himself: a

malade imaginaire

dehydrated by his sixty pipes a day. A young girl asleep, and a young

boy.

Opium should not be for the young, but as the Chinese believe for the

middle-aged and the old. Pipes here cost 10 piastres each (say 2s.).

Then we

went on to a more elegant establishment - Chez Pola. Here one

reserves

the room and can bring a companion. A great Chinese umbrella over the

big

circular bed. A bookshelf full of books beside the bed - it was odd to

find two

of my own novels in a fumerie: Le Ministère de la Peur, and Rocher

de Brighton. I wrote a dédicace in each of them. Here

the pipes cost 30

piastres.

My experience of opium began in October 1951 when I was in Haiphong on the way to

the Baie d' Along. A French official took me after dinner to a small

apartment in

a back street - I could smell the opium as I came up the stairs. It was

like

the first sight of a beautiful woman with

whom one realizes that a relationship is possible: somebody whose

memory will

not be dimmed by a night's sleep.

The madame decided that as I

was a debutant I must have only four pipes, and so I am grateful to her

that my

first experience was delightful and not spoiled by the nausea of

over-smoking.

The ambiance won my heart at once - the hard couch, the leather pillow

like a

brick these stand for a certain austerity, the athleticism of pleasure,

while

the small lamp glowing on the face of the pipe-maker, as he kneads his

little

ball of brown gum over the flame until it bubbles and alters shape like

a

dream, the dimmed lights, the little chaste cups of unsweetened green

tea,

these stand for the' luxe et volupte'.

Each pipe from the moment the

needle plunges the little ball home and the bowl is reversed over the

flame

lasts no more than a quarter of a minute - the true inhaler can draw a

whole

pipeful into his lungs in one long inhalation. After two pipes I felt a

certain

drowsiness, after four my mind felt alert and calm - unhappiness and

fear of

the future became like something dimly remembered which I had thought

important

once. I, who feel shy at exhibiting the grossness of my French, found

myself

reciting a poem of Baudelaire to my companion, that beautiful poem of

escape, Invitation au Voyage. When I got home

that night I experienced for the first time the white night of opium.

One lies

relaxed and wakeful, not wanting sleep. We dread wakefulness when our

thoughts

are disturbed, but in this state one is calm - it would be wrong even

to say

that one is happy - happiness disturbs the pulse. And then suddenly

without

warning one sleeps. Never has one slept so deeply a whole night-long

sleep, and

then the waking and the luminous dial of the clock showing that twenty

minutes

of so-called real time have gone by. Again the calm lying awake, again

the deep

brief all-night sleep. Once in Saigon after smoking I went to bed at

1.30 and

had to rise again at 4.00 to catch a bomber to Hanoi, but in those less three hours

I slept

all tiredness away.

Not that night, but many

nights later, I had a curiously vivid dream. One does not dream as a

rule after

smoking, though sometimes one wakes with panic terror; one dreams, they

say,

during disintoxication, like de Quincey, when the mind and the body are

at war.

I dreamed that in some intellectual discussion I made the remark, 'It

would

have been interesting if at the birth of Our Lord there had been

present

someone who saw nothing at all,' and then, in the way that dreams have,

I was

that man. The shepherds were kneeling in prayer, the Wise Men were

offering

their gifts (I can still see in memory the shoulder and red-brown robe

of one

of them - the Ethiopian), but they were praying to, offering gifts to,

nothing

- a blank wall. I was puzzled and disturbed. I thought, 'If they are

offering

to nothing, they know what they are about, so I will offer to nothing

too,' and

putting my hand in my pocket I found a gold piece with which I had

intended to

buy myself a woman in Bethlehem. Years later I was reading one of the

gospels

and recognized the scene at which I had been an onlooker . “So they

were

offering their gifts to the mother of God,” I thought. 'Well, I brought

that

gold piece to Bethlehem

to give to a woman, and it seems I gave it to a woman after all.'

10 January 1954. Hanoi

With French friends to the

Chinese quarter of Hanoi.

We called first for our Chinese friend living over his warehouse of

dried

medicines from Hong Kong - bales and

bales and

bales of brittle quackery. The family were all gathered in one upper

room with

the dog and the cat - husband and wife, daughters, grandparents,

cousins. After

a cup of tea we paid a visit to a relative - variously known as Serpent

Head

and the Happiest Man in the World. All these Chinese houses have little

frontage, but run back a long way from the street. The Happiest Man in

the

World sat there between the narrow walls like a tunnel, in thin pajamas

- he

never troubled to dress. He was rich and he had inherited the business

from his

father before it was necessary for him to work and when his sons were

already

old enough to do the work for him. He was like a piece of dried

medicine

himself, skeletonized by opium. In the background the mah-jong players

built

their walls, demolished, reshuffled. They didn't even have to look at

the

pieces they drew, they could tell the design by a touch of the finger.

The game

made a noise like a stormy tide turning the shingle on a beach. I

smoked two

pipes as an aperitif, and after dinner at the New Pagoda returned and

smoked

five more.

11 January 1954. Hanoi

Dinner with French friends

and afterwards smoked six pipes. Gunfire and the heavy sound of

helicopters low

over the roofs bringing the wounded from - somewhere. The nearer you

are to

war, the less you know what is happening. The daily paper in Hanoi

prints less than the daily paper in Saigon, and that prints less than

the

papers in Paris.

The noise of the helicopters had an odd effect on opium smoking. It

drowned the

soft bubble of the wax over the flame, and because the pipe was silent,

the

opium seemed to lose a great deal of its perfume, in the way that a

cigarette

loses taste in the open air.

12 January 1954. Vientiane

Up early to catch a military

plane to Vientiane, the administrative

capital

of Laos.

The plane was a freighter with no seats. I sat on a packing case and

was glad

to arrive.

After lunch I made a rapid

tour of Vientiane.

Apart from one pagoda and the long sands of the Mekong

river, it is an uninteresting town consisting only of two real streets,

one

European restaurant, a club, the usual grubby market where apart from

food

there is only the debris of civilization - withered tubes of

toothpaste,

shop-soiled soaps, pots and pans from the Bon Marche. Fishes were small

and

expensive and covered with flies. There were little packets of dyed

sweets and

sickly cakes made out of rice colored mauve and pink. The fortune-maker

of Vientiane

was a man with

a small site let out as a bicycle park - hundreds of bicycles at 2

piastres a

time (say 20 centimes). When he had paid for his concession he was

likely to

make 600 piastres a day profit (say 6,000 francs). But in Eastern

countries

there are always wheels within wheels, and it was probable that the

concessionaire was only the ghost for one of the princes.

Sometimes one wonders why one

bothers to travel, to come eight thousand miles to find only Vientiane

at the

end of the road, and yet there is a curious satisfaction later, when

one reads

in England the war communiqués and the familiar names start from the

page - Nam

Dinh, Vientiane, Luang Prabang -looking so important temporarily on a

newspaper

page as though part of history, to remember them in terms of mauve rice

cakes,

the rat crossing the restaurant floor as it did tonight until it was

chased

away behind the bar. Places in history, one learns, are not so

important.

After dinner to the house of

Mr. X, a Eurasian and a habitual smoker. Thinned by his pipes, with

bony wrists

and ankles and the arms of a small boy, Mr. X was a charming and

melancholy

companion. He spoke beautifully clear French, peering down at his

needle

through steel-rimmed spectacles. His house was a hovel too small for

him to

find room for his wife and child whom he had left in Phnom Penh.

There was nothing to do in the

evening - the cinema showed only the oldest films, and there was really

nothing

to do all day either, but wait outside the government office where he

was

employed on small errands. A palm tree was his bookcase and he would

slip his

book or his newspaper into the crevices of the trunk when summoned into

the

house. Once I needed some wrapping paper and he went to the palm tree

to see

whether he had any saved. His opium was excellent, pure Laos

opium, and

he prepared the pipes admirably. Soon his French employers would be

packing up

in Laos, he would

go to France,

he

would have no more opium - all the ease of life would vanish but he was

incapable of considering the future. His sad amused Asiatic face peered

down at

the pipe while his bony fingers kneaded and warmed the brown seed of

contentment, and he spoke musically and precisely like a don on the

types and

years of opium - the opium of Laos,

Yunan, Szechuan, Istanbul, Benares -

ah, Benares, that was a kind to

remember over the years. *

13 January 1954

On again to Luang Prabang.

Where Vientiane

has two streets Luang Prabang has one, some shops, a tiny modest royal

palace

(the King is as poor as the state) and opposite the palace a steep hill

crowned

by a pagoda which contains - so it is believed - the giant footprint of

Buddha.

Little side streets run down to the Mekong,

here full of water. There is a sense of trees, temples, small quiet

homes, river

and peace. One can see the whole town in half an hour's walk, and one

could

live here, one feels, for weeks, working, walking, sleeping, if the

Viet Minh

were not on their way down from the mountains. We determined, tomorrow

before

returning, to take a boat up the Mekong

to the

grotto and the statue of Buddha which protects Luang Prabang from her

enemies.

There is more atmosphere of prayer in a pagoda than in most churches.

The

features of Buddha cannot be sentimentalized like the features of

Christ, there

are no hideous pictures on the wall, no stations of the Cross, no

straining

after unfelt agonies. I found myself praying to Buddha as always when I

enter a

pagoda, for now surely he is among our saints and his intercession will

be as

powerful as the Little Flower's - perhaps more powerful here among a

race akin

to his own.

After dinner I was very

tired, but five pipes of inferior opium - bitter with dross - smoked in

a

chauffeur's house made me feel fresh again. It was a house on piles and

at the

end of the long narrow veranda, screened from the dark and the

mosquitoes, a

small son knelt at a table doing his lessons while his mother squatted

beside

him. The soft recitation of his lesson accompanied the murmur and the

bubble of

the pipe.

16 January 1954. Saigon .

Laos remained careless Laos

till the end. f was worried by

the late arrival of the car and only just caught the plane which left

the

airfield at 7.00 in the dark. Two stops on the way to Saigon.

I got in about 12.30. Why is it that Saigon

is always so good to come back to? I remember on

my first journey to Africa, when I walked across Liberia,

I used to dream of the

delights of a hot bath, a good meal, a comfortable bed. I wanted to go

straight

from the African hut with the rats

* A connoisseur would say

'The number 1 Xieng Khouang opium of Laos' when referring to the

best

opium from this country. (As, for instance, rubber from Malaya

is described as Number1R.S.S.) Xieng Khouang is a province to the

north-east of Vientiane

where

the best opium is grown.

running

down

the wall at

night to some luxury hotel in Europe

and enjoy

the contrast. In fact one never satisfactorily found the contrast -

either in Liberia

or later in Mexico.

Civilization was always

broken to one slowly: the trader's establishment at Grand Bassa was a

great

deal better than the jungle, the Consulate at Monrovia

was better than the tradesman's house, the cargo boat was an approach

to

civilization, by the time one reached England the contrast had

been

completely lost. Here in Indo-China one does capture the contrast: Vientiane is a century away from Saigon.

18 January 1954

After drinking with M and D

of the Sureté and a dinner with a number of people from the Legation, I

returned early to the hotel in order to meet a police commissioner

(half-caste)

and two Vietnamese plainclothes men who were going to take me on a tour

of Saigon's night side. Our first

fumerie was in the paillote district - a district of

thatched houses in a bad state of repair. In a small yard off the main

street

one found a complete village life - there was a cafe, a restaurant, a

brothel,

a fumerie. We climbed up a wooden ladder to an attic immediately under

the

thatch. The sloping roof was too low to stand upright, so that one

could only

crawl from the ladder on to one of the two big double mattresses spread

on the

floor covered with a clean white sheet. A cook was fetched and a girl,

an

attractive, dirty, slightly squint-eyed girl, who had obviously been

summoned

for my private pleasure. The police commissioner said, 'There is a

saying that

a pipe prepared by a woman is more sweet.' In fact the girl only went

through

the motions of warming the opium bead for a moment before handing it

over to

the expert cook. Not knowing how many fumeries the night would produce

I smoked

only two pipes, and after the first pipe the Vietnamese police

scrambled

discreetly down the ladder so that I could make use of the double bed.

This I

had no wish to do. If there had been no other reason it would still

have been

difficult to concentrate on pleasure, with the three Vietnamese police

officers

at the bottom of the ladder, a few feet away, listening and drinking

cups of

tea. My only word of Vietnamese was 'No,' and the girl's only word of

English

was 'OK,' and it became a polite struggle between the two phrases.

At the bottom of the ladder I

had a cup of tea with the police officers and the very beautiful madame

who had

the calm face of a young nun. I tried to explain to the Vietnamese

commissioner

that my interest tonight was in ambiance only. This dampened the

spirits of the

party.

I asked them whether they

could show me a more elegant brothel and they drove at once towards the

outskirts of the city. It was now about one o'clock in the morning. We

stopped

by a small wayside café and entered. Immediately inside the door there

was a

large bed with a tumble of girls on it and one man emerging from the

flurry. I

caught sight of a face, a sleeve, a foot. We went through to the cafe

and drank

orangeade. The madame reminded me of the old Javanese bawd in South

Pacific.

When we left the man on the bed had gone and a couple of Americans sat

among

the girls, waiting for their pipes. One was bearded and gold-spectacled

and

looked like a professor and the other was wearing shorts. The night was

very

mosquitoes and he must have been bitten almost beyond endurance.

Perhaps this

made his temper short. He seemed to think we had come in to close the

place and

resented me.

After the loud angry voices

of the Americans, the bearded face and the fat knees, it was a change

to enter

a Chinese fumerie in Cholon. Here in this place of bare wooden shelves

were

quiet and courtesy. The price of pipes - one price for small pipes and

one

price for large pipes - hung on the wall. I had never seen this before

in a

fumerie. I smoked two pipes only and the Chinese proprietor refused to

allow me

to pay. He said I was the first European to smoke there and that he

would not

take my money. It was 2.30 and I went home to bed. I had disappointed

my

Vietnamese companions. In the night I woke dispirited by the faults of

the play

I was writing, The Potting Shed, and

tried unsuccessfully to revise it in my mind.

20 January 1954. Phnom Penh

After dinner my host and I

drove to the centre of Phnom

Penh

and parked the car. I signaled to a rickshaw driver, putting my thumb

in my

mouth and making a gesture rather like a long nose. This is always

understood

to mean that one wants to smoke. He led us to a rather dreary yard off

the rue

A -. There were a lot of dustbins, a rat moved among them, and a few

people lay

under shabby mosquito-nets. Upstairs on the first floor, off a balcony,

was the

fumerie. It was fairly full and the trousers were hanging like banners

in a

cathedral nave. I had eight pipes and a distinguished looking man in

underpants

helped to translate my wishes. He was apparently a teacher of English.

9 February 1954. Saigon

After dinner at the

Arc-en-Ciel, to the fumerie opposite the Casino above the school. I had

only

five pipes, but that night was very dopey. First I had a nightmare,

then I was

haunted by squares - architectural squares which reminded me of Angkor,

equal

distances, etc., and then mathematical squares - people's income, etc.,

square

after square after square which seemed to go on all night. At last I

woke and

when I slept again I had a strange complete dream such as I have

experienced

only after opium. I was coming down the steps of a club in St James's Street

and on the steps I met

the Devil who was wearing a tweed motoring coat and a deerstalker cap.

He had

long black Edwardian moustaches. In the street a girl, with whom I was

apparently living, was waiting for me in a car. The Devil stopped me

and asked

whether I would like to have a year to live again or to skip a year and

see

what would be happening to me two years from now. I told him I had no

wish to

live over any year again and I would like to have a glimpse of two

years ahead.

Immediately the Devil vanished and I was holding in my hands a letter.

I opened

the letter - it was from some girl whom I knew only slightly. It was a

very

tender letter, and a letter of farewell. Obviously during that missing

year we

had reached a relationship which she was now ending. Looking down at

the woman

in the car I thought, ‘I must not show her the letter, for how absurd

it would

be if she were to be jealous of a girl whom I don't yet know.' I went

into my

room (I was no longer in the club) and tore the letter into small

pieces, but

at the bottom of the envelope were some beads which must have had a

sentimental

significance. I was unwilling to destroy these and opening a drawer put

them in

and locked the drawer. As I did so it suddenly occurred to me, ‘In two

years'

time I shall be doing just this, opening a drawer, putting away the

beads, and

finding the beads are already in the drawer.' Then I woke.

There remains another memory

which I find it difficult to dispel, the doom-laden twenty-fours I

spent in Dien Bien Phu in January

1954. Nine years later when I

was asked by the Sunday Times to

write on ‘a decisive battle of my choice', it was Dien

Bien Phu that came straightway to my mind.

Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World -

Sir Edward

Creasy gave that classic title to his

book in 1851, but it is doubtful whether any battle listed there was

more

decisive than Dien Bien Phu in 1954.

Even

Sedan, which came too late for Creasy, was only an episode in

Franco-German

relations, decisive for the moment in a provincial dispute, but the

decision

was to be reversed in 1918, and that decision again in 1940.

Dien

Bien Phu, however, was a

defeat for more than the French army. The battle marked virtually the

end of

any hope the Western Powers might have entertained that they could

dominate the

East. The French with Cartesian clarity accepted the verdict. So, too,

to a

lesser extent, did the British: the independence of Malaya, whether the

Malays

like to think it or not, was won for them when the Communist forces of

General

Giap, an ex-geography professor of Hanoi University, defeated the

forces of

General Navarre, ex-cavalry officer, ex-Deuxieme Bureau chief, at Dien

Bien

Phu. (That young Americans were still to die in Vietnam only shows that it

takes

time for the echoes even of a total defeat to encircle the globe.)

The

battle

itself, the heroic

stand of Colonel de Castries' men while the conference of the Powers at

Geneva

dragged along, through the debates on Korea, towards the second item on

the

agenda - Indo-China - every speech in Switzerland punctuated by deaths

in that

valley in Tonkin - has been described many times. Courage will always

find a

chronicler, but what remains a mystery to this day is why the battle

was ever

fought at all, why twelve battalions of the French army were committed

to the

defence of an armed camp situated in a hopeless geographical

terrain-hopeless

for defence and hopeless for the second objective, since the camp was

intended

to be the base of offensive operations. (For this purpose a squadron of

ten

tanks was assembled there, the components dropped by parachute.)

A

commission

of inquiry was

appointed in Paris

after the defeat, but no conclusion was ever reached. A battle of words

followed the carnage. Monsieur Laniel, who was Prime Minister when the

decision

was taken to fight at Dien Bien Phu, published his memoirs, which

attacked the

strategy and conduct of General Navarre, and General Navarre published

his

memoirs attacking M. Laniel and the_politicians of Paris. M. Laniel's book

was called Le

Drame Indo-Chinois and General

Navarre's Agonie

de

l'Indo-Chine,

a

difference in title which represents the difference between the war as

seen in Paris and the war as seen

in Hanoi.

For

the future

historian the

difference between the titles will seem smaller than the contradictions

in the

works themselves. Accusations are bandied back and forth between the

politician

who had never visited the scene of the war and the general who had

known it

only for a matter of months when the great error was made.

The

war, which

had begun in

September 1946, was, in 1953, reaching a period for the troops not so

much of

exhaustion as of cynicism and dogged pride - they believed in no

solution but

were not prepared for any surrender. In the southern delta around

Saigon it had

been for a long while a war of ambush and attrition - in Saigon itself

of

sudden attacks by handmade and bombs; in the north, in Tonkin, the

French

defence against the Viet Minh depended on the so-called lines of Hanoi established by

General de Lattre. The lines were not real lines; Viet Minh regiments

would

appear out of the rice-fields in sudden attacks close to Hanoi itself before they

vanished

again into

the mud. I was witness of one such attack at Phat Diem, and in Bui Chu,

well

within the lines, sleep was disturbed by mortar-fire until dawn. While

it was

the avowed purpose of the High Command to commit the Viet Minh to a

major

action, it became evident with the French evacuation of Hoa Binh, which

de

Lattre had taken with the loss, it was popularly believed, of one man,

that

General Giap was no less anxious to commit the French army, on ground

of his own

choosing.

Salan

succeeded de Lattre,

and Navarre

succeeded Salan, and every year the number of officers killed was equal

to a

whole class at Saint-Cyr (the war was a drain mainly on French

officers, for

National Service troops were not employed in Indo-China on the excuse

that this

was not a war, but a police action). Something somewhere had to give,

and what

gave was French intelligence in both senses of the word.

There

is a bit

of a

schoolmaster in an intelligence officer; he imbibes information at

second hand

and passes it on too often as gospel truth. Giap being an ex-professor,

it was

thought suitable perhaps to send against him another schoolmaster, but·

Giap

was better acquainted with his subject - the geography of his own

northern

country.

The

French for

years had been

acutely sensitive to the Communist menace to the kingdom of Laos

on their flank. The little umbrageous royal capital of Luang Prabang,

on the

banks of the Mekong, consisting mainly

of

Buddhist temples, was threatened every campaigning season by Viet Minh

guerrilla regiments, but I doubt whether the threat was ever as serious

as the

French supposed. Ho Chi Minh can hardly have been anxious to add a

Buddhist to

a Catholic problem in the north, and Luang Prabang remained inviolate.

But the

threat served its purpose. The French left their 'lines'.

In

November

1953, six

parachute battalions dropped on Dien Bien Phu,

a plateau ten miles by five, surrounded by thickly wooded hills, all in

the

hands of the enemy. When I visited the camp for twenty-four hours in

January

1954, the huge logistic task had been accomplished; the airstrip was

guarded by

strongpoint’s on small hills, there were trenches, underground

dug-outs, and

miles and miles and miles of wire. (General Navarre wrote with Maginot

pride of

his wire.) The number of battalions had been doubled, the tanks

assembled, the

threat to Luang Prabang had been contained, if such a threat really

existed,

but at what a cost.

It

is easy to

have hindsight,

but what impressed me as I flew in on a transport plane from Hanoi, three hundred

kilometres

away, over

mountains impassable to a mechanized force, was the vulnerability and

the

isolation of the camp. It could be reinforced - or evacuated - only by

air,

except by the route to Laos,

and as we came down towards the landing -strip I was uneasily conscious

of

flying only a few hundred feet above the invisible enemy.

General

Navarre writes with

naivete and pathos, 'There was not one civil or military authority who

visited

the camp (French or foreign ministers, French chiefs of staff, American

generals) who was not struck by the strength of the defences …. To my

knowledge

no one expressed any doubt before the attack about the possibilities of

resistance.' Is anyone more isolated from human contact than a

commander-in-chief?

One

scene of

evil augury

comes back to my mind. We were drinking Colonel de Castries' excellent

wine at

lunch in the mess, and the colonel, who had the nervy histrionic

features of an

old-time actor, overheard the commandant of his artillery discussing

with

another officer the evacuation of the French post of Na-San during the

last

campaigning season. De Castries struck his fist on the table and cried

out with

a kind of Shakespearian hysteria, 'Be silent. I will not have Na-San

mentioned

in this mess. Na-San was a defensive post. This is an offensive one.'

There was

an uneasy silence until de Castries' seconding-command asked me whether

I had

seen Claudel's Christophe Colombe as I passed through Paris. (The officer who

had

mentioned Na-San

was to shoot himself during the siege.)

After

lunch,

as I walked

round the intricate entrenchments, I asked an officer, 'What did the

colonel

mean? An offensive post?' He waved at the surrounding hills: 'We should

need a

thousand mules - not a squadron of tanks - to take the offensive.'

M.

Laniel

writes of the

unreal optimism which preceded the attack. In Hanoi optimism may have

prevailed,

but not in

the camp itself. The defences were out of range of mortar fire from the

surrounding hills, but not an officer doubted that heavy guns were on

the way

from the Chinese frontier (guns elaborately camouflaged, trundled in by

bicycle

along almost impassable ways by thousands of coolies - a feat more

brilliant

than the construction of the camp). Any night they expected a

bombardment to

open. It was no novelist's imagination which felt the atmosphere heavy

with

doom, for these men were aware of what they resembled - sitting ducks.

In

the

meanwhile, before the

bombardment opened, the wives and sweethearts of officers visited them

in the

camp by transport plane for a few daylight hours: ardent little scenes

took

place in dug-outs - it was pathetic and forgivable, even though it was

not war.

The native contingents, too, had their wives - more permanently - with

them,

and it was a moving sight to see a woman suckling her baby beside a

sentry

under waiting hills. It wasn't war, it wasn't optimism - it was the

last

chance.

The

Viet Minh

had chosen the

ground for their battle by their menace to Laos. M. Laniel wrote

that it would

have been better to have lost Laos

for the moment than to have lost both Laos and the French

army, and he

put the blame on the military command. General Navarre in return

accused the

French Government of insisting at all costs on the defence of Laos.

All

reason for

the

establishment of the camp seems to disappear in the debate - somebody

somewhere

misunderstood, and passing the buck became after the battle a new form

of

logistics. Only the Viet Minh dispositions make sense, though even

there a

mystery remains. With their artillery alone the Communists could have

forced

the surrender of Dien Bien Phu. A man cannot

be evacuated by parachute, and the airstrip was out of action a few

days after

the assault began.

A

heavy fog,

curiously not

mentioned by either General Navarre or M. Laniel, filled the cup among

the

hills every night around ten, and it did not lift again before eleven

in the

morning. (How impatiently I waited for it to lift after my night in a

dug-out.)

During that period parachute supplies were impossible and it was

equally

impossible for planes from Hanoi

to spot the enemy's guns. Under these circumstances why inflict on

one's own

army twenty thousand casualties by direct assault?

But

the Great

Powers had

decided to negotiate, the Conference of Geneva had opened in the last

week of

April with Korea

first on the agenda, and individual lives were not considered

important. It was

preferable as propaganda for General Giap to capture the post by direct

assault

during the course of the Geneva Conference. The assault began on 13

March 1954,

and Dien Bien Phu fell on 7 May, the day before the delegates turned at

last

from the question of Korea

to the question of Indo-China.

But

General

Giap could not be

confident that the politicians of the West, who showed a certain guilt

towards

the defenders of Dien Bien Phu while they were discussing at such

length the

problem of Korea, would have continued to talk long enough to give him

time to

reduce Dien Bien Phu by artillery alone.

So

the battle

had to be

fought with the maximum of human suffering and loss. M. Mendes-France,

who had

succeeded M; Laniel, needed his excuse for surrendering the north of

Vietnam

just as General Giap needed his spectacular victory by frontal assault

before

the forum of the Powers to commit Britain and America to a division of

the

country.

The

Sinister

Spirit sneered:

'It had to be!'

And

again the Spirit of Pity

whispered, 'Why?'